The Mediterranean became de iure a Greek and, still more, Athenian sea.

By Dr. V.L. Konstantinopoulos

Ancient Historian

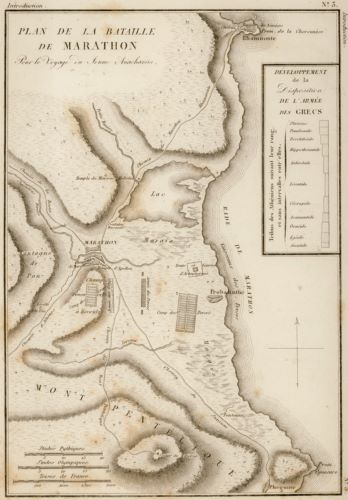

The victory of Athens at Marathon1 at the beginning of September 490 BC had immense importance for the establishment of Athens as a ruling force in the Greek world. The decisiveness of the Athenians, amplified by a deep commitment to the cause of Greek freedom from Persian domination and by their superior tactical skill, constituted in retrospect a landmark in the salvation of Greece and the beginning of what was to become a new collective security system that was founded after the end of the Persian Wars under the title of the First Athenian or Delian League. The purpose of that League, namely the liberation of the Greek cities from Persian control, after the successful naval and land operations of Kimon, son of Miltiades, was in essence fulfilled when the defeated Persians were obliged:

a) to give Greek cities and islands from Imbros to Cyprus their freedom;

b) to retreat to a distance of three days’ march from the Ionian shores; and

c) not to conduct any naval activity in the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea.

Consequently, the Mediterranean became de iure a Greek and, still more, Athenian sea (in a move which prefigured the Roman concept of a mare nostrum).

That critically important pact between East and West, the so-called ‘Peace of Callias’, was concluded in 449 BC. The terms of the pact are known to us from Diodorus (12.4); it appears to be alluded to at Herodotus 7.151 but astonishingly is completely ignored by Thucydides, although it is implied in some passages (II 62.2 and VIII 56.4).2 After 449 BC the Athenians, without any external threats, were free to consolidate their naval dominance under the leadership of Pericles, thus changing the fundamental basis of the Delian League. In this period, the underlying rivalry with the Spartans was intensified and a state of cold war was established.

The Periclean policy justified its imperial outlook on the basis of the Athenians’ crucial role in the battle of Marathon and the naval battle of Salamis. Arguments justifying Athenian claims to dominance were promoted in epitaphioi, which were not a simple ornament of the burial ceremony but helped to reinforce the collective identity of existing Athenian citizens and inculcated the general guidelines of patriotic ideology by which future generations of citizens were shaped. The speech of the Athenian ambassadors in Sparta (432 BC) that Thucydides gives us is a typical specimen of this patriotic ideology (1.73.4):3

Therefore, we argue that we alone fought the barbarians …

This μόνοι (‘alone’) constitutes an indirect accusation against Sparta, whose help the Athenians requested to face the Persians. That the Spartans did not send help on the grounds of the celebration of the Karneia, despite the fact that, stricto sensu, this was an important moment for their city, left the Athenians to their fate but at the same time left them to resist alone and begin the creation of an historic role (in every sense) as saviours of Greece. Therefore, the Athenians rightfully claimed that they alone, namely without the help of the Spartans, fought the Persians, whose mere name (at least according to Herodotus) had scared the Greeks until then (Hdt. 6.112.3: τέως δὲ τοῖσι Ἕλλησι καὶ τὸ οὔνομα τὸ Μήδων φόβος ἀκοῦσαι). The fact that the word μόνοι is aimed here against Sparta is strongly supported by the presence of the 1000 Plataean soldiers, who fought the Persians bravely but whose presence is ignored in μόνοι.4 However, it was the Spartans whose help Athens needed, since they were the mightiest land power in Greece, and it was the Spartans whose support the Athenians especially sought.

This official argument of the Athenian patriotic ideology is adopted by Lysias in his Epitaphios (2.20):5

Therefore, we alone risked our lives fighting against tens of thousands of barbarians defending the whole of Greece.

If Lysias adopted this opinion due to his own commitment to the democracy and his family’s attested association with Pericles, the conservative circles of Athens, which included Plato and Isocrates and which from Kimon’s era promoted friendship and alliance with the Spartans, took a different view of the facts. According to Plato (Mx. 240c):6

None of the Greeks assisted the Eretrians or the Athenians except the Spartans; they arrived the next day.

The effect of this is to diminish the Athenian claim to have been alone, since the Spartans sent help, which arrived on the day after the battle. Therefore, in his version it seems that they delayed only one day and not ten, as was the case. The important thing here is that the Spartans sent prompt help to the Athenians. Furthermore, according to Isocrates (Panegyricus 60):7

Just when the Spartans were informed of the war in Attica, they set aside all their other obligations and came to help us, so fast, as if it was their country that was besieged.

That is, the Spartans abandoned everything and sent help, as though it was their city under siege, immediately they learned of the Persians’ disembarking in Attica. But notice again, the fact that the Spartans were slow to help and arrived ten days later is not mentioned at all.

The difference in political beliefs, then, had a profound effect on historical perspective. The same situation may be observed even more intensely in the case of the naval battle of Salamis. More precisely, the Athenian ambassadors in Thucydides continuing their speech contend that (1.74.1):

We offered three things that proved to be very useful in this fight, namely the greatest number of ships and a very wise general and an untiring eagerness to fight: more specifically, slightly less than two thirds of the whole number of ships in the sea battle, Themistocles as the general, who was the main advocate of a sea battle in a small area of sea that indisputably saved the situation.

That is to say that the Athenians offered the greatest number of ships, one very skilled general, namely Themistocles, whose strategic plan helped defeat the Persians, and their presence, which was of decisive importance at the naval battle of Salamis.8 That these points do not originate with Thucydides but were actually used by the Athenian ambassadors is proved by 1.18.1-2,9 where Thucydides’ own version of the Persian Wars lacks such pro-Athenian elements. On the contrary, he states that both the Athenians and the Spartans defeated the Persians. In relation to the battle of Marathon, Thucydides merely mentions that the battle happened between the Persians and the Athenians (1.18.1), without writing that the victory of the Athenians saved Greece and without stressing that they fought alone against the Persians (κοινῇ ἀπωσάμενοι τὸν βάρβαρον).

However, the early origin of the patriotic arguments of the Athenian ambassadors is proved by Herodotus, who gives his opinion that the Athenians saved Greece, noting that it is one that can cause envy, but is true nonetheless (7.139):10

If someone states now that the Athenians became the saviours of Greece, he would tell the truth.

Moreover, Herodotus’ narrative (8.44-48) confirms the triple argument of the Athenians, first that the Athenians offered the greatest number of ships, namely 180 of the total fleet of 378 ships. With regard to Themistocles’ plan, Herodotus (8.57ff.) mentions that he convinced the Spartans to change the initial plan of defence, which entailed that the sea battle should be fought not in the narrow space of Salamis but on the open sea where, as Themistocles observed, the Persian fleet with the greater number of ships could circle the Greeks and defeat them. Furthermore, Herodotus writes that Themistocles used his subordinate Siccinus to drive the Persians into the narrow space of Salamis and make the allies give battle there. Therefore, historically, there is no doubt that the Athenians with Themistocles were the main contributors to the victory in Salamis. Naturally, Athenian foreign policy at the time of Pericles used these arguments to amplify Athens’ claim to a ruling position and educate the citizens with the patriotic ideology that is depicted in the funeral orations.

The same arguments for the dominant role that the Athenians played at the naval battle of Salamis are found in Lysias’ Epitaphios (2.42):

They contributed the most and the best for the freedom of the Greeks, that is to say the general Themistocles, who was very skilled in talking, in comprehending things and in doing, more ships than the other allies, and men with great naval abilities.

In contrast, the help that the Spartans gave at Salamis was represented by the Athenians an act of selfishness, the purpose of which was to protect the Spartans themselves. That is stressed by the Athenian embassy in Thucydides (1.74.3):

You assisted because you were worried about yourselves more than you were about us …

Here the Spartans’ help is disregarded and underestimated. The Athenian envoys also emphasized the strategic plan of Themistocles, which involved the Greeks fighting the Persians on sea and not on land, as the Spartans proposed, who planned to raise successive walls in Isthmus. The fact that those walls were useless, since the Persians had overwhelming numerical superiority at sea and could disembark an army from there and surround the Peloponnesian defensive position, was stressed by the Athenians from very early on to emphasize the argument that the victory at Salamis was an Athenian achievement. Just as Herodotus (7.139) and the Athenian embassy (Thuc. 1.73.4), so do Lysias (2.44) and Isocrates (4.98) highlight the self-serving attitude of the Spartans, who wanted the Isthmus to be the battlefield to preserve their own safety. Moreover, they stress the selflessness of the Athenians, who abandoned their houses to fight for the freedom of all Greeks. Therefore, according to Lysias (2.46) the Athenians were considered by all worthy to become rulers of Greece (ἠξιώθησαν ὑπὸ πάν τωνἡγεμόνες γενέσθαι τῆς Ἑλλάδος).

The Athenian confrontation with Sparta was not restricted to Athens’ foreign policy but had an impact on its internal policy as well, since the conservative elite circles disliked democracy and sea power alike, as one may see in the Pseudo-Xenophontean Athenian Constitution. Therefore, the battle of Marathon and the sea battle of Salamis were inevitably drawn into ideological conflicts between the democrats and the oligarchs. The former believed that the naval battle of Salamis was more important than the battle of Marathon, owing to the fact that after their defeat at Salamis, the Persians retreated. Consequently, it became obvious that the salvation of Greece was owed to the ships, which were manned by the poorer citizens (Thuc. 1.73.5):

The greatest proof was given by them [the Persians]; because when they were defeated in the sea battle … they retreated quickly with the greatest part of their army … it became obvious that the salvation of Greece was owed to the ships.

Plato, however, renders greater honours to the Marathon-fighters than those who fought at Salamis (Mx. 241a):

The first prize must be given to them with our speech, while the second prize must be given to those who fought in Salamis …

The ideological substrate of this judgment is revealed by Laws 707a-c:11

… and the land battles (namely in Marathon and in Plataea) made the Greeks better, while the others (namely in Salamis and Artemision) made the Greeks worse.

It is mentioned there that the soldier is more stable and braver than the mariner, because the latter, when the enemies attack, will not die staying in his position but leaves shamelessly (706c). Furthermore, a sea victory is owed to many and the mariner is not distinguished, as is the soldier in battle. Due to these facts, the battle of Marathon is of greater importance in social and ethical terms than the naval battle of Salamis and made the Greeks better, while the sea battles made them worse.

This underestimation of the poor that manned the ships had already started by the second quarter of the fifth century BC, when the politician Ephialtes with Pericles stripped the Areopagus of power and gave it to the popular Ekklesia. From then, elitist hostility to the dēmos was amplified, as one can see in Pseudo-Xenophon’s Athenian Constitution.12 The fact that even the high moments of Athenian history could be evaluated in different ways is the downside of the intense political confrontation which Moses Finley has identified as essential to democracy.13 Subsequent ages, with the benefit of distance, have tended to see the two together as part of the larger legend of Athens as (in Herodotus’ words) the saviours of Greece and as symbols of a nation which sees any sacrifice for freedom as the κάλλιστοςἔρανος (‘the best contribution’).

Endnotes

- See in general The Cambridge ancient history vol. IV (Cambridge 1988) 506-17.

- See further The Cambridge ancient history vol. V (Cambridge 1992) 121-27. The existence of the Peace of Kallias has been disputed since the fourth century and remains a hotly contested topic. The literature is vast; see in particular D. Stockton, ‘The peace of Callias’, Historia 8 (1959) 61-79; A. J. Holladay, ‘The détente of Kallias?’, Historia 35 (1986) 503-07; E. Badian, ‘The peace of Callias’, JHS 107 (1987) 1-39; S. Hornblower, A commentary on Thucydides vol. 1 (Oxford 1991) 179-81; G. L. Cawkwell, ‘The peace between Athens and Persia’, Phoenix 51 (1997) 115-30; P. J. Rhodes, A history of the classical Greek world, 478-323 BC (Oxford 2006) 47-48.

- See further J. de Romilly, Thucydides and Athenian imperialism (Oxford 1963); C. Mossé, Périclès, L’inventeur de la démocratie (Paris 2005) 48ff.

- For μόνοι see also Markantonatos, Volonaki, Xanthaki Karamanou, and in this volume pp. 75, 170, 176, 215.

- See further S. Usher, Greek oratory. Tradition and originality (Oxford 1999) 350; J. Walz, Der lysianische Epitaphios, Phil. Suppl 29.4 (Leipzig 1936). On the problem of authenticity, see J. Klowski, Zur Echtheitsfrage des lysianischen Epitaphios (Hamburg 1959); on the style see Usher ibid.; R. C. Jebb, The Attic Orators from Antiphon to Isaeus, 2 vols (London 1876, Greek trans. Athens 2008) 1.57-96; for comments see S. C. Todd, A commentary on Lysias, speeches 1-11 (Oxford 2007) 210-74.

- See further R. Thurow, Der platonische Epitaphios (Tübingen 1968); Usher, Greek oratory (n. 5 above) 351-52.

- See E. Buchner, Der Panegyricus des Isokrates, Historia Einzelschriften 2 (Wiesbaden 1958); Usher, Greek oratory (n. 5 above) 298-301, 320-21, 350.

- Cf. Hornblower, A commentary on Thucydides vol. 1 (n. 2 above) 119. On the numbers of ships at Salamis, see Hdt. 8.43-48, with A. M. Bowie, Herodotus. Histories book VIII (Cambridge 2007) ad loc.; C. Carey et al., ‘Fragments of Hyperides’ Against Diondas from the Archimedes palimpsest’, ZPE 165 (2008) 1-19, at 16.

- For the possibility that those words are a piece of a funeral oration and, more specifically, for the fallen of the Samian war see V. L. Konstantinopoulos, ‘Thuk. I 73,2-74,3. Beitrag zur Forschung der attischen Leichenreden’, Plato 50 (1998) 190-212. For the ideological content of the funeral orations see also in this article 207ff.

- See W. W. How and J. Wells, A commentary on Herodotus (Oxford 1912) at 7.139, that the opinion belongs to Herodotus. This is contradicted by what the Athenian ambassadors say at Thuc. 1.73.4, which proves that those words belonged to the argumentation of Periclean foreign policy.

- See T. L. Pangle, The Laws of Plato (Chicago 1980) 375ff.

- See further, e.g., J. Ober, Mass and elite in democratic Athens: rhetoric, ideology, and the power of the people (Princeton 1989).

- M. I. Finley, ‘The Athenian demagogues’, Past and Present 21 (1962) 3-24.

Contribution (63-68) from Marathon – 2,500 Years, edited by Christopher Carey and Michael Edwards (University of London Press, 12.02.2013), Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.