The funeral speech offers the audience a model to be imitated and thus contributes to the timeless epainos and excellence of the polis.

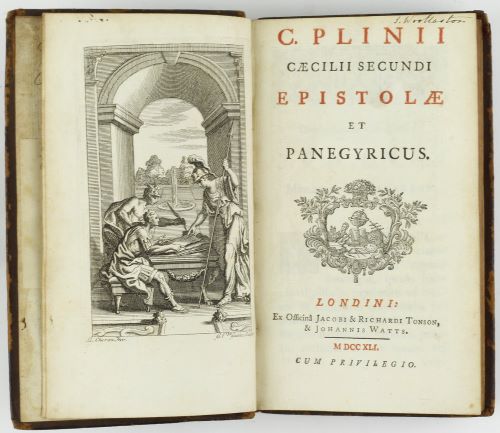

By Dr. Eleni Volonaki

Assistant Professor of Ancient Greek Literature

University of Peloponnese

The conventional conception of epideictic as a discourse of ‘praise and blame’, familiar from Aristotle, is neatly summed up in the distinction of the types of oratory in Aristotle, Rhet. 1358b:

The concern of counsel/advice (symboulē) is partly exhortation, partly dissuasion. For in every case people who offer private advice and people who speak in public on civic issues do one or the other of these. The concern of the lawsuit is partly accusation, partly defence. For inevitably people in dispute do either of these. The concern of display is partly praise and partly blame.

According to this categorization of the three ‘species’ of rhetoric – judicial, deliberative, epideictic – which remained fundamental in the history of classical rhetoric, a speech is called ‘epideictic’ if the audience is not being asked to take a specific action, unlike forensic and deliberative oratory, which seek to have a practical outcome and make the audience reach a decision. Nevertheless, epideictic oratory served practical goals and was of ideological importance. It gave the opportunity to skilful orators and politicians to impress their audiences and advertise their own political ideals. It could also play an important role in rhetorical education, since it demonstrated methods of argumentation.1 Furthermore, epideictic oratory could influence opinion in the city of Athens by offering advice and criticism. The concept of epideictic oratory needs to be broadened beyond the limitations of fourth-century rhetorical theory.2

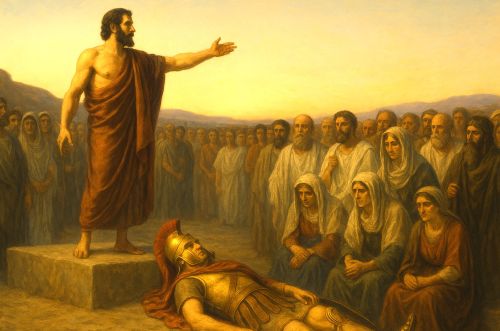

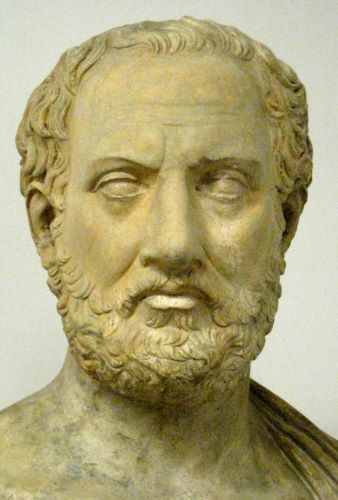

The funeral oration, the example par excellence of this category, played an important role in its civic setting; it reviewed the achievements of the mythical and historic past of the city of Athens, both celebrating and setting an example of virtue in political life, and finally it provided pieces of advice and counsel for the consolation of the living. In the process it also cemented and enhanced the status of the speaker. The funeral orations (epitaphioi) were delivered as part of a state burial ceremony. Thucydides, in his introduction to Perikles’ funeral oration (2.34), gives us our fullest account of this tradition, which was celebrated annually, whenever there were Athenian war-dead to bury.3 The ceremony consisted of four stages: the prothesis, where the remains of the dead bodies were brought in the coffins, one for each of the ten Athenian tribes; the ekphora – a formal procession to the public cemetery, named the Kerameikos; the burial in the dēmosion sēma;4 and finally the funeral oration delivered by a chosen, distinguished orator. Just as the occasion reflects a democratization of traditional elite practice, so the surviving funeral speeches reflect a democratic reading of Athenian history. In Homer’s world, funeral ceremonies were restricted to the individual aristocrat, but in democratic Athens they were anonymous and collective, since they represented ordinary Athenian soldiers (particularly hoplites) and not their leaders. The precise date of the introduction of the public burial ceremony is controversial but it probably began in the late 470s or early 460s.5 As to the delivery of an oration, this institution may have been one of the later additions to the public funeral. Our evidence of the surviving epitaphioi starts from 431 BC – the date of Thucydides’ funeral oration, but the reference to the practice of delivery in its introduction indicates that it must already have been established. Demosthenes’ statement in his speech Against Leptines (141), ‘you alone of all men make public funeral orations for the dead’, suggests that the custom was considered uniquely Athenian.

A speaker at a public burial ceremony is under pressure to say something significant and original. On the other hand, he needs to satisfy audience expectations which involve traditional cultural ideals, such as patriotism, freedom under the law, self-confidence, and public democratic debate, and to articulate these through a set of typical narrative components.6 All the surviving speeches display a common structure, and later rhetoricians refer to these same typical elements for funeral orations. In the proem the speaker explains that his words are inadequate to the occasion. The epainos or ‘praise’ section follows, which included standard mythological and historical exploits, one of which was the praise of the ancestors and their accomplishments. In the final section, the speaker should give some consolation to the relatives of the dead.

In reviewing the past history of the city, the victory mainly of the Athenians in the Persian Wars was a rhetorical topos, widely used in all kinds of oratory and especially in epideictic funeral orations, as a unique and exemplary act of bravery in the cause of freedom for the Greeks. Our emphasis in this article will be placed on the use of the battle of Marathon as a topos of reference in setting an example of virtue, education, and political life. A detailed examination of all surviving epitaphioi will show that the particular example from the history of the city was used in different ways depending on the context for which each oration was composed and in connection with the evolution of Athenian history from the second half of the fifth to the end of the fourth century BC.

Thucydides’ epitaphios is arguably the boldest reworking of the funeral oration.7 Its specific political goal, which is to glorify the Athenian democracy, gives it a very unusual relationship with the deeds of the ancestors. The epainos begins with praise of the progonoi (ancestors) by asserting (2.36.1):

I will begin with our ancestors; it is both just and proper that to them first be given the honour of remembrance on an occasion of this kind. For the same people having been always in succession the inhabitants of this land, by their valour they have delivered it to us in the state of liberty.

This is the only reference made to the ancestors. Thucydides moves to the next generation by saying that καὶ ἐκεῖνοί τε ἄξιοι ἐπαίνου καὶ ἔτι μᾶλλον οἱ πατέρες ἡμῶν ·κτησάμενοι γὰρ πρὸς οἷς ἐδέξαντο ὅσην ἔχομεν ἀρχὴν οὐκ ἀπόν ως ἡμῖν τοῖς νῦν προσκατέλιπον (2.36.2: ‘for which they deserve commendation, but our fathers deserve yet more; for in addition to what they had received, not without great labour of their own have they acquired this our present dominion and delivered it to us in the present generation’), a statement that may undermine the glory of the more distant ancestors – the generation of the Pentekontaetia are important because they acquired the empire. Finally, Perikles’ own generation follows, which is praised for strengthening the empire and making Athens self-sufficient in all aspects, for both war and peace (2.36.3):

We ourselves who are present here and are for the most part in the prime of life have enlarged and furnished the city with everything, both for peace and for war, such that it is now self-sufficient.

The largest part of the speech concentrates on the Athenian way of life and nothing is said of the past Athenian achievements and history. No reference to the Persian Wars or the battle of Marathon is made in the funeral oration, though the narrator notes in his introduction that the dead from the Marathon battle were, exceptionally, buried on that site.

The real subject of the praise in Perikles’ epitaphios is the Athenian way of life, not its historical antecedents. The remarkable rhetorical achievement of Perikles here lies in the way he blends the past and the present in a ‘timeless encomium of the city’; the city of Athens is praised as a city worth dying for.8 Perikles avoids referring to the achievements of the ancestors, since 431 had been a year of invasion and destruction; the first year of the war was marked by lack of military and political success. Therefore, any comparison between the past and the present would open up negative reactions and criticism.

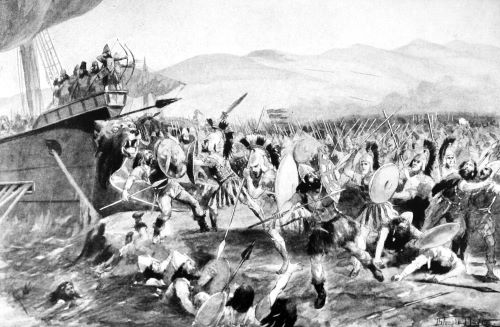

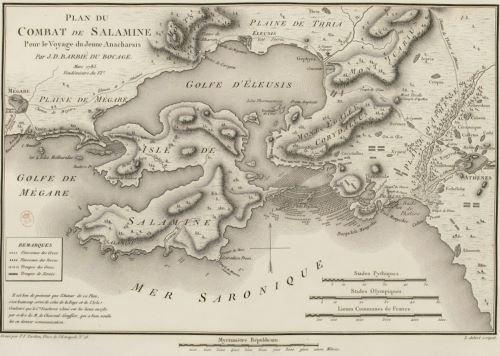

Perikles’ silence is not however reflected in Athenian rhetoric in Thucydides more generally. Praise of the men of Marathon and Salamis is placed in the mouths of the ambassadors at Sparta and Euphemus at Syracuse (1.73.4-74.4, 6.82.3), who emphasize the risks taken in those battles as part of a rhetoric which justifies the empire on the basis of Athens’ panhellenic contribution. In both cases, the Athenians are praised for securing the freedom of Greece; at Marathon they fought unaided against the barbarians, whereas at Salamis they sacrificed their land in order to fight the enemy in the sea battle.

We have what looks like a near-contemporary funeral oration composed by Gorgias, the famous sophist from Leontini. It survives only in fragments and there is not much to conclude about the content or the rhetorical topoi included. It is unlikely that Gorgias actually delivered this funeral oration since he was not an Athenian citizen. Gorgias’ epitaphios was most probably written as a demonstration speech for students of rhetoric and as an example of what a funeral oration should look like. But that if anything adds to its value for a reconstruction of the proprieties of the genre.

The first fragment (1.5: ‘Xerxes, the Zeus of the Persians’) indicates that the speech must have contained an account of the Persian Wars, commonly included in the section on Athenian history. The most extensive fragment of Gorgias’ funeral oration (4.6) clearly deals with praise of the dead, and it appears that this type of praise was ordinarily presented in the epainos. For the dead the epainos refers to their noble death and their sacrifice of life in order to benefit their country. The topos of the victory of the few over the immense power of the enemy in funeral orations aims to glorify and idealize the achievement of the dead, as for example the triumph of the Athenians in the battle of Marathon.

Gorgias must have also had a political objective since he criticized the Athenians for their fighting against fellow-Greeks (5b: ‘trophies over the barbarians call for hymns of praise, those over Greeks call for lamentations’). Philostratos (Lives of the Sophists 1.9 [493]) states that Gorgias advocated a reconciliation between the Greek states involved in the Peloponnesian War. This was an agenda also pursued in Gorgias’ Olympikos, where the theme of Greek homonoia is used, as in Lysias’ and Isokrates’ Olympic speeches, to enhance the ideal and concept of panhellenic unity at Olympia; it is also stressed for deliberative ends, urging the audiences of the Olympic Games to take action against the barbarians. The epitaphios, however, is much bolder, since its form suggests that it was delivered in Athens (since this seems to have been a particularly Athenian genre) and that it engages very daringly with the Athenian tradition.9 This is a singularly subversive use of the Athenian genre, which for historical reasons invariably figured the burial of those who died fighting Greeks. Gorgias (it seems) uses the Athenians’ achievements against the Persians to contrast the contemporary wars and to urge them to fight against the common foe.

The epitaphios attributed to Lysias was composed during the Corinthian War of 395-87 for those who died ‘assisting the Corinthians’. Due to the clear divergence of the funeral speech from the rest of the corpus Lysiacum,10 its authenticity has been questioned;11 on balance I am inclined to accept authenticity on the grounds that it accords with what we know of Lysias,12 though we may doubt that it was actually delivered.13

Modern scholars view Lysias’ epitaphios as an example of a typical funeral oration of the period.14 Lysias’ epainos is taken almost completely from the genos and extends to over sixty sections. Such a lengthy mythical-historical narrative is often considered the most typical and important part of classical funeral orations.15 Lysias develops the epainos chronologically according to three broad divisions, the ancestors (§§ 3-19), their descendants (§§ 20-66), and those now being buried (§§ 67-70). For our purposes, we will focus on the description of the wars with Darius (§§ 20-26). This first section of the historical narrative suppresses the Ionian Revolt and consequently Athens’ participation in the sack of Sardis, the Persian sack of Eretria in the run-up to the Marathon campaign, and the Plataean support for Athens at Marathon. In effect, the Persians are depicted as the aggressors and the Athenians are praised as the isolated defenders and saviours of Hellas: ‘for they alone risked their lives against many myriads of barbarians in defence of the whole of Greece’.16 It is unlikely that Datis and Artaphernes intended to capture Greece – they focused on Athens and Eretria – but the panhellenic project of 480 is here retrojected to cover the much more narrowly focused Marathon campaign.17

Strikingly, in chapter 20, the victors of Marathon are represented as the descendants of their mythological forefathers and not as the ancestors of the deceased:

For indeed, being of noble birth and having minds as noble, the ancestors of those who lie here have achieved many good and admirable things, while their descendants have everywhere left behind them memorable and mighty trophies owing to their virtue.

Though Lysias probably draws on an ancestral tradition where the victors of Marathon have been idealized and stereotyped within Athenian history, it is striking that Lysias will praise Salamis ‘as the greatest of Athenian victories’ (2.40-42) and Marathon comes in second place. Salamis offers much better ground for idealization of the Athenian contribution to the larger Greek cause. Though Salamis gets more space, Marathon is rewritten in a creative way which plays effectively to the political agenda of this speech.18

Lysias’ account of Marathon includes a degree of exaggeration of numbers19 and in § 21 he reports the figure of a 500,000-strong Persian army, which is directly paralleled only in Plato’s Menexenos (240a6), as we shall discuss further below; Isokrates in his Panegyrikos (4.86) simply has ‘many myriads’ and nowhere else is a figure given. Lysias wishes to emphasize the importance of the Athenian victory by picking up the themes of altruism and isolation. In this context, he goes on to explain extensively the Persians’ thinking for choosing to disembark to Marathon: they believed that they would defeat the Athenians without any interference from other Greek cities (21-22):

They believed that if they could either obtain the willing friendship of our city or force it unwillingly, they would easily gain control of the rest of the Greeks. So, they sailed to Marathon, thinking that we should be most destitute of allies if they made their venture while Greece was still divided how best to repel the invaders.

In addition, because of previous actions of our city they retained a particular opinion of the Athenians: that if they attacked any other city first, they would be at war with it and Athens as well, because the Athenians would eagerly come to rescue those who were being wronged; but if they came here first, the rest of the Greeks would not dare to defend another city, creating open hostilities with Persia.

The praise of the Athenians implied here involves two ideals of the Athenian supremacy. First, the Athenians succeeded in subverting so many Persians, even though the Persians had believed in their own victory as secure and certain. Secondly, the Athenians’ superiority is emphatically reflected in the allegation that they would have supported any other Greek city if it had suffered such an invasion first – a kind of altruism that appears to have scared the enemy. The implication, of course, is that contrary to the Athenians’ self-sacrifice, the other Greek cities did not run to help. It is interesting the way in which Lysias retrojects the Greek disunity of 481-80, which figures so prominently in Herodotos, again making this an Athenian lone championship of a common Greek cause rather than a defence of Attica.

In § 23 Lysias draws on the typical characteristic of funeral orations to praise not the lives of the citizens but their choice of death.20 There is an extensive account of the reasons for which the Athenians rushed to send the army out to Marathon without waiting for the allies to hear the news and come to help; the emphasis on their direct response elides the fact that the Spartans arrived late because they waited until the full moon, as stated in Herodotos’ narrative (6.105.1); the narrative also ignores the support that they did receive from the Plataians, even though it was not well received.21 The Athenians considered that they alone should save Greece and therefore decided to act thus to defend their own ideals of glorious death, virtue, and courage, which appear to reflect an epic value (2.23):

Our ancestors took no account of military danger but reckoned that a glorious death leaves behind an immortal fame. They did not fear the multitude of their adversaries, but rather had confidence in their own ability. They were ashamed that the barbarians were in their country, and did not wait till their allies should be informed and help them; rather than have to thank others for their safety, they chose that the rest of the Greeks should be in debt to them.

In §§ 24-25 Lysias praises the ancestors for their bravery, generosity, and virtue in establishing a trophy for Greece over the barbarians. They were driven out of respect for the laws rather than fear for the enemy.22 Their self-sacrifice is underlined again in § 26, emphasizing the misleading assertion that Athens did not receive nor even send for help.23

It has become clear that Lysias manipulates the Athenians’ victory at Marathon rhetorically in order to isolate their heroic choice of death and exaggerate their altruistic resistance, as is reflected in the closing statement:

It is not surprising, therefore, that, due to the deeds performed long ago, even today their merit is praised by all men, as if their actions were still new.

The uniquely high status of the Athenian victors of Marathon obtained a mythical dimension, as is widely attested in literature;24 the exemplary virtue of the men of Marathon is to be admired and imitated by all generations. Though Salamis receives more space in this speech, the way in which Marathon is rewritten gives it a powerful suggestiveness of its own.

Lysias’ speech offers us the best example of the ‘Greek patriotism’ reading of Marathon. The speech was composed within the period of the Corinthian War, when the Athenians had joined Corinth, Argos, and Thebes in revolt against Sparta. The ancestors are praised at such a length and with such pronounced exaggeration to encourage the Athenians to aid the Corinthians; the enmity against the Spartans is apparent, since they were at this stage the main cause of struggle among the Greeks. Lysias’ epitaphios tries to support the earliest attempts to reconstruct the Athenian empire; thus it presents a contrast between the glorious Athenian power and the negative depiction of the Lakedaimonian hegemony. Despite its epideictic style, occasion, and content, Lysias’ funeral oration has many features of a symbouleutic narrative and is effective in that it calls for a return to the past – a theme central to fourth-century Athenian politics. He appeals to the Athenian ideals of self-sacrifice, salvation of Greece, and heroic death, moving between ‘repetition and renewal’ at a time when ‘hegemonic discourse’ was limited and the Spartans were about to win the war with Persian support.25 The funeral oration, though theoretically just about display, also responds very subtly to the politics of the moment.

The battle of Marathon, attributed to the generation of πάλαι, is used as an example of the virtue shown in the past that is to be remembered as if it were recent; thus, the quality of the ancestors’ deeds is effectively used to form a continuum in Athens’ history. The continuity of the Athenians’ achievements appears so strong that the past and present are blurred in order to present Athenian virtue as a constant and continuous merit. As Grethlein has rightly pointed out, ‘this effective use of the traditional and exemplary modes of memory enables the funeral speeches to make contingency of chance virtually disappear at an occasion that ritually reflects on the strongest experience of contingency, death’.26

As has been stated, there are similarities in the epainos of the ancestors between Lysias’ epitaphios and the funeral oration that has been incorporated into Plato’s dialogue Menexenos. The historical detail in the speech indicates that it was written after the Corinthian War and Lysias’ funeral oration, though its fictive date is the 420s. Socrates presents a funeral oration by Aspasia, the well-known mistress of Perikles, and the ascription to Aspasia establishes a connection between Plato’s Menexenos and the famous Periklean funeral oration by Thucydides. Scholars differ in their interpretation of the dialogue:27 some see the speech as an antagonistic response to Thucydides’ idealized view of Athenian democracy under Perikles, whereas others see it as a sort of parody that adopts an ironic tone on Lysias’ epitaphios. On any reading this speech, despite its lack of real ceremonial occasion, offers as serious an engagement with Athenian politics as any other instance of the form.

Many parallels can be observed between Plato’s and Thucydides’ orations, such as the antithesis of word and deed (logos and ergon), the tradition of the funeral oration, and the emphasis placed upon paideia and politeia.28 There are, however, differences between the two orations concerning the individual and collective ideal of virtue, the vocabulary, the tone, and approach to the audience.29 Despite the polemical relationship between the two orations, the Menexenos can be seen as an alternative and an answer to the Periklean oration in two aspects, the rhetoric and the politics. It offers an analysis of the faults of rhetoric by recognizing the falsehood of the idealized portrayal of Athens, which in effect becomes an object of parody in Socrates’ funeral oration.30 Thus, Plato takes the opportunity to demonstrate how a funeral oration should be written. In terms of politics, the contrast between the two figures Perikles and Socrates is obvious; the former represents the prestige of the Athenian empire and naval power, whereas the latter reflects the ideals of virtue (Socratic aretē) and justice. Plato’s target is the construction of Perikles as a symbol, and he criticizes Thucydides’ portrayal and the Athenian practice, particularly in the funeral oration, of exemplifying Perikles, his leadership, and his policy.31 Thus, the appeals to the traditions of Athenian history are presented in order to offer a judgement against Perikles’ imperial policy.

Plato’s epainos (239a6-246b2) is treated in a long section that includes the stories of the mythical background and a survey of Athenian history from the Persian Wars down to the Peace of Antalkidas in 387 BC. Plato makes no distinction between the deeds of the present dead and the deeds of their ancestors. His strongest resemblances are with Lysias. In particular the closeness of the relationship between the two texts can be seen in the description of the battle of Marathon, though there are significant differences as well.

Plato praises the dead for their virtue as they set an example to imitate in later battles (240d):

It is by realizing this position of affairs that we can appreciate what manner of men those were, in point of virtue, who defended against the barbarians’ power and punished the pride of all Asia, and were the first to raise trophies of victory over the barbarians; whereby they pointed the way to the others and taught them to know that the Persian power was not invincible, since there is no multitude of men or wealth but courage conquers it.

The most obvious overlap in theme and subject matter with Lysias’ epitaphios is the emphasis placed in both speeches on Athens as champion of liberty, who alone defeated the barbarians, and also the size of the Persian army at Marathon, rated by both authors as fifty myriads. There are, however, two points in Plato’s narrative that may indicate that his version is meant to undermine Lysias’ praise of the Athenian hegemony. Plato subverts Lysias’ silence concerning the Athenian support in sacking Sardis at the outbreak of the Ionian Revolt and the Persians’ sailing first against Eretria before attacking Marathon by giving these details as a pretext for Darius’ expedition. The first detail presents a more aggressive Athens, whereas the second undermines the claim that the Athenians were isolated and unsupported. Plato stresses the active support of the Spartans, while noting their late arrival,32 as reported in Herodotos’ description of the battle.

The praise of the ancestors and their victories in the Persian Wars reveals an educative tone, since their action has set an example for imitation, which however was not consistently followed by the post-war generations. The ancestors are depicted as ἡγεμόνεςκαὶδιδάσκαλοι, and Plato stresses the importance of the battle of Marathon both for subsequent Greek resistance to the barbarian and for the Athenians of his time to honour the memory of the dead by ‘living well’.33

Plato uses the historic example of the battle of Marathon not only to criticize the political circumstances in Greece following the Corinthian War but also probably to influence the policy of his city after his first return from Sicily.34 Beyond the antagonistic relationship between the Menexenos oration on the one hand and the Periklean funeral oration and Lysias’ epitaphios on the other hand, which was analysed above, Plato intends to offer advice drawing on the common theme in epideictic oratory, the appeal for panhellenic unity, i.e. the need for concord between the Greek cities in the face of Persian intrusion. Thus, Socrates’ oration appeals to tradition but his attack on Perikles’ imperial policy and the rhetorically exaggerated idealization of the past of Athens, as presented in Lysias’ funeral oration, is meant to underline the importance of Socratic aretē and the ideal of moral integrity for the improvement of contemporary Athenian politics.

The last two surviving epitaphioi are the only ones which were ‘certainly’ delivered on the occasion of a burial ceremony. In 338 BC, Demosthenes was chosen by the Athenians to deliver the funeral oration over those Athenians who had died fighting Philip II at the battle of Chaironeia.35 There has been a dispute about the authenticity of the funeral speech that has been preserved to us, on the basis of its stylistic differences from Demosthenes’ surviving oratory and the fact that it does not follow the conventional structure of a funeral oration. Its distinctiveness, however, in genre and content is not a sufficient reason for discarding it as not a genuine work of Demosthenes.36 As was noted above in the case of Lysias’ epitaphios, epideictic oratory allows for a more elaborate style and syntax as well as extemporaneous elements. Given that Demosthenes has been traditionally considered to have delivered his Funeral Oration after the battle of Chaironeia,37 it seems plausible that the oration known to us is a reworking of the original funeral speech performed by him in 338 BC.

The defeat of the Athenians, the Thebans, and the Boiotians by Philip II signalled the beginning of the end for the independent Greek city-states of the classical period. The epitaphios had to deal with a terrible defeat, which involved an enemy who was not Greek. Therefore, the section on the genos is very brief, in particular the reference to the Persian Wars (60.10):

Those alone twice repulsed both by land and by sea the navy that had assembled from the whole of Asia, and in debt of their individual risks they caused the joint salvation of all the Greeks.

The Persian Wars are singled out from the history of the city and the battles of Marathon and Salamis are highlighted for bringing security and freedom for all the Greeks. It is striking that here again the Athenians are referred to as fighting ‘alone’ (μόνοι) against the Persians in defence of the freedom of all Greeks.

At the beginning of the fifth century BC the battle of Marathon signalled the rise of the Athenian hegemony and its growth within the Greek world. Almost a century later, the battle of Chaironeia signalled the complete fall of Athenian power and the rise of the Macedonian hegemony. The contrast between the Athenian victory of Marathon and the Athenian defeat in Chaironeia might seem too intense to leave space for an extended praise of the ancestors. The praise is focused on the dead, their virtue and courage, and their self-sacrifice in order to indicate that they deserve honour from the living. Demosthenes departs from the tradition outlined in the previously described speeches by praising the men as children and adults before their service as soldiers (15-24); the emphasis is on the topoi paideia and epitedeusis. In order to counteract any hint of failure on the part of the dead, Demosthenes states that all those who die in battle have no share in defeat but should all equally share in victory (60.19); he also criticizes the Theban commanders for their performance on the battlefield (60.18, 22). The epainos may be directed toward the present rather than the historic past of the Athenians, but Demosthenes connects the eulogy for both the ancestors and the dead by depicting the birth link which joins the latter to their ancestors by birth (60.12). Demosthenes’ epitaphios contains the sad immediacy of the recent defeat and a gap opens between the legendary past and the present.38 Nevertheless, the ancestors are used as a point of reference to underline the praise of the dead, whose death has set an example of nobility and freedom. The model of the Persian Wars is still used rhetorically to heroize the Athenian effort at Chaironeia. He praises the Athenians for following a policy that aimed at the freedom of the Greeks just as before, drawing an explicit analogy between the campaign of 338 and the Persian Wars.

Finally, Hyperides’ epitaphios was delivered in 322 BC at a burial ceremony in the form we have now,39 at the end of the first season of the so-called Lamian War, which was largely successful for the Greeks, though the general Leosthenes, a friend of Hyperides, was killed. The speech was presented after the initial victory in Boiotia, the siege at Lamia, and the defeat of Leonnatus (12-14). Later that year the Athenian fleet suffered two major losses and the army was defeated soon afterwards. The war was a complete failure for the Greeks. More than one thousand Athenians died and two thousand were taken hostage; the rest of the Greeks also suffered losses. As a result, the Athenians had to submit to Macedonian terms while Hyperides and Demosthenes, the leading opponents of Macedonian involvement in Greek affairs, were condemned to death by the Athenian dēmos.40 Hyperides’ funeral oration highlights the Athenian policy of resistance to Macedon.41

Hyperides gives more details of the occasion of death than the earlier speakers. The oration provides an unusual amount of specific historic detail and discusses the general Leosthenes at length. Hyperides underlines that Leosthenes deserves more praise than his predecessors whereas earlier epitaphioi praise the deeds of the dead for being equivalent to those of their ancestors. A description of the war in which the men died is uncommon in the funeral speeches, let alone the focus so exclusively on one person.42 Hyperides brings an innovation to the traditional themes and structure of epitaphioi logoi by inserting a picture of the present;43 he adapts the standard content of the genre to the immediate historical context. He deliberately rejects any reference to the past, explaining his decision at the outset with a firmness reminiscent of Perikles’ epitaphios. Hyperides emphasizes the virtues of the Athenians of the present, wishing probably to encourage and mobilize them to fight, though the war was in the end unsuccessful. Hyperides’ innovation lies in the fact that the standard account of the Persian Wars has been replaced by an account of recent events. Furthermore, the description of the heroes in the Lamian War echoes the language and ideas typically used to depict the role of the Athenians in the Persian Wars, as for example § 9: ‘I think it is simplest to narrate their courage in war and how they were responsible for many benefits to their fatherland and to the other Greeks’;44 §16: ‘those who died in the war and gave up their lives for the freedom of the Greeks, considering that the clearest proof of their willingness to provide freedom to Greece was dying for it in battle’;45 § 24: ‘these men acquired immortal glory for the price of a mortal body and with their own individual virtue they secured common freedom for the Greeks’,46 etc47

To conclude, there is a variation in the use of the topoi of genos, of the ancestors’ virtues, of Athenian history, and in particular the Athenian victory at the battle of Marathon by the surviving epitaphioi. Nevertheless, they do not entirely depart from the theme that the ancestors set an example by offering freedom to all Greece, which is peculiar to the genre. There is a shifting relationship between the epitaphioi and the evolution of the city and thus a change from the hēgēmonikos logos of Perikles to the eulogy and individual praise of Hyperides, where the emphasis shifts from the praise of the past to the praise of the present. As has been shown, in the earlier funeral orations the Persian Wars and in particular the battle of Marathon serve the idealization of Athens, whereas toward the end of the fourth century BC the historical past is adapted to present history and the battles involved. Thus, an evolution can be observed in the development of the genre within a period of more than one hundred years (431-322 BC) in the emphasis of content and language depending on the political circumstances at a given battle and time.

Our surviving epitaphioi cannot be included in one and the same group, since they were not all delivered at a public burial nor are they all dated to the same period. The central themes of all the speeches are the ‘noble death’ and the ‘freedom’ of Greece due to the achievements of the ancestors and the dead from specific battles. The tone of funeral orations is both educative and symbouleutic; the orators attempt to influence public opinion for resistance and continuing the war, and the emphasis placed upon the battle of Marathon has been transformed to that purpose.

The funeral orations attributed to Gorgias and Lysias, and the one included in Plato’s Menexenos are all literary works composed for publication or public recitation rather than actual performance at burial ceremonies. As exemplary pieces of rhetorical training, the three funeral speeches concentrate on the epainos of the history of Athens; a shift can be seen, however, in the use of the historical battles of the Persian Wars from Gorgias’ to Plato’s work, since the orators apply the deeds of the ancestors earlier as memorable and later as instrumental examples. In all cases, the exemplary modes of memory are effectively used to guide the present generation, who are invited to emulate their forefathers. The funeral speeches function as ‘action’ speeches, since there is a ‘dialectical relationship between words and deeds’.48 The symbouleutic character of the funeral speech contributes to the continuity and regularity in the history of the city of Athens. The funeral speech offers the audience a model to be imitated and thus contributes to the timeless epainos and excellence of the polis.

The funeral orations supposedly composed by Perikles, Demosthenes, and Hyperides to be delivered in honour of the dead at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War, after the defeat in the batle of Chaironeia, and during the Lamian War respectively present a different form of the epainos section. The appeals to the tradition of Marathon, and the Persian Wars in general, are either brief or non-existent. The emphasis in all three speeches is placed upon the present. In Perikles’ oration the Persian Wars are not mentioned at all, but the most extensive part of the epainos section involves the Athenian constitution. In Demosthenes’ funeral speech, the reference to Marathon and Salamis may be brief but is emphatically incorporated in the praise of the dead, who had fought worthily of their ancestors; still the epainos focuses on the dead rather than their ancestors. Finally, in Hyperides’ oration the past has been replaced by the present but the idealization of Athens in the Persian Wars is emphatically reflected and adjusted to the heroic resistance against Macedon. It can be thus assumed that in the actual funeral orations which were delivered at burial ceremonies, the tradition of Marathon is not explicitly used to praise the heroic past but is adapted to the praise of recent events, and the individual leaders may reflect the glory of the famous Themistokles and Miltiades, though their heroism is more distinctly eulogized.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Contribution (165-179) from Marathon – 2,500 Years, edited by Christopher Carey and Michael Edwards (University of London Press, 12.02.2013), Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.