Illustration of Plato’s allegory of the cave / Yale University, Creative Commons

By Dr. Steven Smith / 09.20.2006

Alfred Cowles Professor of Government & Philosophy

Yale University

Republic Books I-II

Introduction

This is the book that started it all. The Apology, the Crito, these are warm-ups to the big theme, to the big book, the Republic. Every other book in this political science that has since been written, beginning with Aristotle’s Politics and moving on to the present day is, in one way or another, an answer, a response to Plato’s Republic. It started the whole thing.

The first and most obvious thing to say about the Republic is that it is a long book. Not the longest book you will ever read, but long enough. In fact, in part, because of this, we are only reading approximately half the book, the first five books, to be more specific. The first five books that deal with and culminate in the best city, Plato’s ideal city, what he calls Kallipolis, the just city, the beautiful city, ruled by philosopher-kings. The second half of the book turns in somewhat different, certainly equally important directions, and we won’t deal with that here.

What Is Plato’s Republic About?

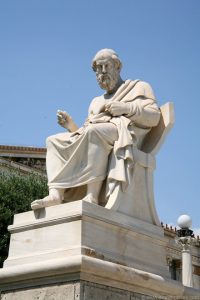

Statue of Platon, with Athena statue behind, outside Athens Academy / Wikimedia Commons

So let’s start by asking a simple question. What is the Republic about? What does this book deal with? This is a question that has perplexed and divided readers of Plato almost from the beginning. Is it a book about justice, as the subtitle of the book suggests? Is it a book about what we today might call moral psychology and the right ordering of the human soul, which is a prominent theme addressed in this work? Is it a book about the power of poetry and myth, what we would call the whole domain of culture to shape souls and to shape our societies? Or is it a book about metaphysics and the ultimate structure of being, as certainly many of the later books of the Republic suggest? The theory of the forms, the image of the divided line and so on and so on. Of course, it is about all of these things and several others as well. But at least at the beginning, when we approach the book, we should stay on its surface, not dig at least initially too deeply.

As one of the great readers of Plato of the last century once said, “Only the surface of things reveals the essence of things.” The surface of the Republic reveals that it is a dialogue. It is a conversation. We should approach the book, in other words, not as we might a treatise, but as we might approach a work of literature or drama. It is a work comparable in scope to other literary masterworks–Hamlet, Don Quixote, War and Peace, others you might think of. As a conversation, as a dialogue, it is something the author wants us to join, to take part in. We are invited to be not merely passive onlookers of this conversation, but active participants in that dialogue that takes place in this book over the course of a single evening. Perhaps the best way to read this book is to read it aloud, as you might with a play, to yourself or with your friends.

Let’s go a little further. The Republic is also a utopia, a word that Plato does not use, was not coined until many, many centuries later by Sir Thomas More. But Plato’s book is a utopia. It is a kind of extreme. He presents an extreme vision of politics. He presents an extreme vision of the polis. The guiding thread of the book is the correspondence, and we will look at this in some length and you will discuss it in your sections, no doubt. The guiding thread of the book is the correspondence, the symmetry between the parts of the city and the parts of the soul. Discord within the city, just as discord within the soul, is regarded as the greatest evil. The aim of the Republic is to establish a harmonious city, based on a conception of justice that, so to speak, harmonizes the individual and society, how to achieve that. The best city would necessarily be one that seeks to produce the best or highest type of individual. Plato’s famous answer to this is that this city–any city–will never be free of conflict, will never be free of factional strife until, in his famous formula, kings become philosophers and philosophers become kings.

The Republic asks us to consider seriously, what would a city look like ruled by philosophers? In this respect, it would seem to be the sort of perfect bookend to the Apology. Remember, the Apology viewed the dangers posed to philosophy and the philosopher and the philosophical life from the city. The Republic asks us, what would a city be like if it were ruled by Socrates or someone like him? What would it be like for philosophers to rule? Such a city would require, so Socrates tells us throughout the opening books, the severe censorship of poetry and theology, the abolition of private property and the family, at least among the guardian class of the city, and the use of selected lies and myths, what would today probably be called ideology or propaganda, as tools of political rule. It would seem that far from utopia, theRepublic represents a radical dystopia, a satire, in some sense, of the best polity. In fact, much of modern political science is directed against Plato’s legacy. The modern state, as we have come to understand it, is based upon the separation of civil society from governing authority. The entire domain of what we call private life separated from the state. But Plato’s Republic recognizes no such separation or no such independence for a private sphere. For this reason, Plato has often been cast as a kind of harbinger of the modern totalitarian state.

A famous professor at a distant university was said to have begun his lectures on the Republic by saying, “Now we will consider Plato, the fascist.” This was, in fact, the view popularized by one of the most influential books about Plato written in the last century, a book written by a Viennese émigré by the name of Karl Popper, who in the very early 1950s, right at the height of the Cold War and of course the end of the conclusion of the Second World War, wrote a book calledThe Open Society and Its Enemies. He wanted to know what were the causes or who was responsible for the experiences of totalitarianism, both in Stalin’s Russia and in Hitler’s Germany. In the course of this inquiry, he concluded that not only Hegel and Marx were important in that particular genealogy, but this went back to Plato as well, Plato principally. Plato, who Popper accuses in a passionate, albeit not very well written book, accuses Plato of being the first to establish a kind of totalitarian dictatorship. Is that true?

Plato’s Republic is, we will discover as you read, a republic of a very special kind. It is not a regime like ours devoted to maximizing individual liberties, but it is one that puts the education of its citizens, the education of its members, as its highest duty. The Republic, like the Greek polis, was a kind of tutelary association. Its principal good, its principal goal, was the education of citizens for positions of public leadership and high political responsibilities. It is always worthwhile to remember that Plato was, above all, a teacher. He was the founder of the first university, the Academy, the Platonic Academy, where we will find out later Aristotle came to study, among many others–Aristotle being but the most famous. Plato was the founder of this school. This, in turn, spawned other philosophical schools throughout the Greek world and later, the Roman world. With the demise of Rome, in the early Christian centuries, these philosophical academies, these philosophical schools, were absorbed into the medieval monasteries. These, in turn, became the basis of the first European universities in places like Bologna, Paris, Oxford.

These were, in turn, later transplanted to the New World and established in towns like Cambridge and, of course, New Haven. We can say today that this university is a direct ancestor of the platonic republic of Plato’s Academy. We are all here the heirs of Plato. Think of that. Without Plato, no Yale. We would not be here today. I think that is a fact. Just ponder that for a moment. In fact, let me even say a little more about this. The institutional and educational requirements of Plato’s Republic share many features with a place like Yale. For example, in both the Platonic Kallipolis, the just city, as well as this place, men and women–men and women–are selected at a relatively early age because of their capacities for leadership, for courage, for self-discipline, and responsibility. They spend several years living together, eating together in common mess halls, exercising together, and studying together, of course, far from the oversight of their parents. The best of them are winnowed out to pursue further study and eventually assume positions of public leadership and responsibility. Throughout all of this, they are subjected to a course of rigorous study and physical training that will lead them to adopt prominent positions in the military and other branches of public service. Does this sound at all familiar to you? It should. Let me put it another way. If Plato is a fascist, what does that make you? Plato, of course, is an extremist. He pushes his ideas to their most radical conclusions. That’s what it is to be a philosopher. But he is also defining a kind of school. He regards the Politea or the Republic, because that is the original Greek title of the book, Politea or regime. He regards the politea as a school whose chief goal is preparation for guidance and leadership of a community.

If you don’t believe me about this, maybe you will consider the words of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of the great readers of Plato’s Republic. Rousseau wrote in his Emile, “To get a good idea of public education,” he says, “read Plato’s Republic. It is not a political treatise, as those who merely judge books by their title think, but it is the finest, most beautiful work on education ever written.” Rousseau. So, there we go.

“I Went Down to the Piraeus”

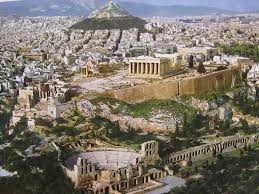

Piraeus port, Athens / Wikimedia Commons

Let’s now peek into the book itself. Just peek. We won’t go too far. Let’s start with the first line. Who remembers what the first line is? Oh, come on. You should know this. You’re looking at the book. You’re cheating. “I went down to the Piraeus.” I went down to the Piraeus. Why does Plato begin with this line? There’s a story that I heard. I’m not sure if it’s altogether true, but it’s a good story, at least, about the famous German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who said that on his first teaching of the Republic, he went through the whole book, taught the whole book in one seminar, one semester. The last time he taught it, the final time he taught it, he never got beyond the first sentence, “I went down to the Piraeus.” What does it mean? Why does he begin with this? “I went down,” a going down. The Greek word for this is catabasis. “I had made a descent.”

There is a book by a famous contemporary to Plato. It’s a man named Xenophon, who wrote a book called the Anabasis. The anabasis means a going up, an ascent. But Plato begins this dialogue with this stigma. “I went down.” The descent to the Piraeus. It is clearly modeled on Odysseus’ descent to Hades in the Odyssey. In fact, the work is a kind of philosophical odyssey that both imitates Homer, but also anticipates other great odysseys of the human mind, works by those like Cervantes or Joyce. The book is full, you will see, of a number of descents and ascents. The most famous climb upward, although we will not actually read these parts for this class, concerns the climb to the divided line, the famous image of the divided line in Book VI, and the ascent to the world of the imperishable forms. Then, in the last book of the Republic, Book X, there is, once again, a descent to the underworld, to the world of Hades. The work is not, in a sense, written simply as a sort of timeless philosophical treatise, but as a dramatic dialogue with a setting, a cast of characters and a firm location in time and place.

Let’s say a little more about that time and place already indicated in the sentence, “I went down to the Piraeus.” Plato was born in 427, which is four years after the commencement of the Peloponnesian War. He was a young man of 23 when the democracy in Athens was defeated. He was only 28 when the restored democracy executed his friend and teacher, Socrates, in 399. Almost immediately after the trial of Socrates, Plato left Athens and traveled extensively throughout the Greek world. Upon his return, he established this school at Athens he called the Academy, for the training of philosophers, statesmen, and legislators. Plato lived a long time. He lived until the age of 80. Except for two expeditions to Sicily, where he went at the request of Dionysius to help try to establish a philosophical kingship in Syracuse, he remained in Athens teaching and writing. The Republic belongs to that period of Plato’s work after his return to Athens, after the execution of Socrates.

The Seventh Letter

The platform on the Pnyx and actual remain in Athens where speakers stood to address the Athenian democratic assembly in the 5th century BCE. The space dedicated for the assembly could hold 6000 people. / Wikimedia Commons

The dominant feature of Plato’s political theory, David Grene, a great reader of Plato, has said is “the root and branch character of the change it advocates and existing institutions.” Plato’s desire for a kind of radical makeover, of Athenian and Greek political institutions and cultures, grew out of his experience of political defeat and despair. The utopianism of the book is, in many ways, the reverse side of the sense of profound disillusionment that he felt at the actual experience of the Athenian polis. This was not only true of his experience at home, but of his failed efforts to turn Dionysius’ kingship in Sicily into a successful example of philosophical rule. In fact, we have–and I want to read to you in just a moment–a lengthy transcript of Plato’s own account of why he came to write the Republic. One thing, of course, you note in theRepublic, is that Plato is nowhere present. He is not a participant in his own dialogue. He is the author, but not the participant.

We don’t know precisely what Plato thought, but we are helped, at least, by a kind of intellectual autobiography that he wrote and that we still have, in what is conventionally referred to as The Seventh Letter. Plato wrote a series of letters that we have. People have argued over the authenticity of them, although I think by now it is established that they are his. In the most famous of these letters, the lengthy seventh one, he gives us, again, something of an autobiography and tells us a little bit about why he came to write this book. Isn’t this amazing that 2,000-2,500 years ago, we still have the letters of the man who wrote this book? Let me read to you what Plato says about how he came to write this book. “When I was a young man,” he said–and this is written as he is very old. “When I was a young man, I felt as yet many young men do. I felt at the very moment I attained my majority I should engage in public affairs. And there came my way an opportunity that I want to tell you about. The democratic constitution, then loudly decried by many people, was abolished. And the leaders of the revolution set themselves up as a government of 30 men with supreme authority.”

He’s referring to the Tyranny of the Thirty that existed after the Athenian defeat. “Some of these men [some of the members of the Thirty], you must understand, were relatives of mine and well known to me. And what is more, they actually invited me at once to join them, as though politics and I were a fit match. I was very young then and it is not surprising that I felt as I did. I thought that the city was then living a kind of life which was unjust and that they would bend it to a just one and so administer it more justly. So I eagerly watched to see what they would do. And you must know, as I looked on, I saw those men in a short time make the former democracy look like a golden age.”

He is referring to his relatives, men like Critias and Charmides, who turned Athenian politics into a tyranny and, which he says, makes the “democracy look like a golden age.” Let me continue in Plato’s words. “I looked at this, you see, and at the men who were in politics, at the laws and customs. And the more I looked and the older I grew, the more difficult it seemed to me to administer political affairs justly. For you cannot do so without friends and comrades you can trust. In such men it was not easy to find. For the city, you see, no longer lived in the fashion and ways of our fathers. Eager as I had once been to go into politics, as I look at these things and saw everything taking any course at all with no direction or management, I ended up feeling dizzy. I did not abandon my interest in politics to discover how it might be bettered in other respects, and I was perpetually awaiting my opportunity. But at last, I saw that as far as all states now existing are concerned, they are all badly governed. For the condition of their laws is bad almost past cure, except for some miraculous accident. So I was compelled to say, in praising true philosophy, that it was from it alone that was able to discern any justice. And so I said that the nations of the world will never cease from trouble until either the true breed of philosophers shall come to political office or until that of the rulers shall, by some divine law, take the pursuit of philosophy.”

There you see in that wonderful and a kind of probing self-examination of his early motives and expectations, you see the disillusionment of the older Plato looking on what the Tyranny had done. But also looking at the states, the nations of his time, seeing their management, seeing their decay and conflict and saying and suggesting that no justice will ever be expected until, as he says at the end, kings become philosophers and philosophers kings, a direct reference to theRepublic. This little autobiography, goes on at considerably greater length, I should say. But this provides a kind of introduction, as it were, to the Republic. We have in Plato’s own words here, the way he viewed politics and his reasons for his political philosophy. Yet, in many respects, if the Republic was the result of comprehensive despair and disillusionment with the prospects of reform, the dialogue itself points back to an earlier moment in Plato’s life and the life of the city of Athens. This remarkable letter was written when Plato was very old, approximately 50 years after the trial and execution of Socrates. But the action of the Republic takes place long before the defeat of Athens, before the rise of the Thirty and the execution of Athens [correction: should have said Socrates]. It refers to that period that Plato says in the letter looked like “a golden age, when many things seemed possible.” That brings us back to the opening, the descent to the Piraeus.

Analyzing the Beginning of Republic and the Hierarchy of Characters

1785 Bocage Map of Athens and Environs, including Piraeus, in Ancient Greece / Wikimedia Commons

The action of the dialogue begins at the Piraeus, the port city of Athens, somewhere around the year 411, during what was called the Peace of Nicias, that is to say, the peace that endured a kind of respite, truce that was established during the fighting between Sparta and Athens. At the very beginning of the dialogue, we see Socrates and his friend Glaucon. What are they doing?

They are walking back to Athens from the Piraeus. But maybe to put it a slightly different way, they’re trolling the waterfront. What is the Piraeus? It is the harbor of Athens. What do you expect from harbors? What are harbor cities like? What do you find down at harbors?

You find various kinds of disreputable and maybe unseemly things going on there. We are forced to ask ourselves: What are Socrates and Glaucon doing there? Why are they there together? What are they doing? What do they expect to find? These seem to be questions that immediately come to mind. We learn shortly afterwards that they have taken this descent to the Piraeus to view a festival, a kind of carnival. It sounds like something one might expect to see in a Fellini film. A kind of carnival, a carnivale, a Mardi Gras, where a festival is going on. What’s more, a new goddess is being introduced into the pantheon of deities. This seems to suggest that–referring back to the Apology, that it is not Socrates, but the Athenians who innovate, who create and introduce new deities. Socrates remarks that the Thracians, the display of the Thracians, put on a good show, showing that his own perspective is not simply bound by that of a city. It suggests, from the beginning, a kind of loftiness and impartiality of perspective characteristic of the philosopher, but not necessarily the citizen.

On their way back from this festival, from this carnival, on their way back they’re accosted, you remember. They’re accosted by a slave who’s been sent on by Polemarchus and his friends and who orders Socrates and Glaucon to wait. “Polemarchus orders you to wait,” the slave says. He orders you to wait. He is coming up behind you. Just wait. “Of course we’ll wait,” Glaucon replies. When Polemarchus and his friends arrive, we find that his friends include Adeimantus, who is Glaucon’s brother and Niceratus, who is the son of Nicias, the general who has just brokered the peace that they are now enjoying. That’s the famous Peace of Nicias. They challenge Socrates. “Stay with us or prove stronger.” Stay with us or prove stronger. “Could we not persuade you?” Socrates asked. “Could we not persuade you to let us go?” “Not if we won’t listen,” Polemarchus says. Instead, they reach a compromise. But Socrates and Glaucon come with Polemarchus and the others to the home of Polemarchus’ father, where dinner will be provided for them, and later, a return to the festival where there will be a horseback race. “It seems,” Glaucon says, “we must stay.” And Socrates concurs.

Why does the book begin with this, let’s say, opening gambit? Is it simply a ruse to get the reader’s attention in some sense or to rope you in with some promise of what’s to follow? Already from the very opening lines we see in this a clue to the theme that is going to follow. Who has the title to rule? Is it Polemarchus and his friends who claim to rule by strength of numbers? “Can we persuade you?” “Not if we don’t listen,” he says. Or Socrates and Glaucon, who hope to rule by the powers of reason, speech, and argument? Can we convince you? Can we persuade you? Can democracy that expresses the will of the majority, the will of the greater number be rendered compatible with the needs of philosophy and the claims to respect only reason and a better argument? That seems to be the question already posed in this opening scene. Can a compromise be reached between the two? Can the strength of numbers, as well as respect for reason and a better argument be, in some sense, harmonized? Can they be brought together? Is the just city, perhaps, that Socrates will later consider, a combination of these two–of both force and persuasion? That will be something left to see. But I think you can see the big themes of the book already very present in the opening scene of the dialogue. The first book is really a kind of preamble to everything that follows. Okay? Are you with me so far on this?

Let’s talk a little bit about the participants in this dialogue. It is a dialogue. It has a fairly large number of characters, although only a relatively few number of them speak in the book. Yet, it’s something very important, as we would want to know in any play or novel or movie. We want to note something about the particular people who inhabit this dinner party that Socrates and Glaucon have been promised. Who are they and what do they represent? There is Cephalus, who we will see very quickly, the father of Polemarchus and whose home they are attending. The venerable paterfamilias, the venerable father of the family. Polemarchus, his son, a solid patriot who defends not only his father’s honor, but that of his friends and fellow citizens. We will also see Thrasymachus, a cynical intellectual who rivals Socrates as an educator of future leaders and statesmen. Of course, it is the exchange between Socrates and Thrasymachus that is one of the most famous moments of the book.

Cephalus

Tripartie soul illustration / La Audacia de Aquiles, Wikimedia Commons

There is, in the first set of dialogues, a distinct hierarchy of characters, you might say, who we see later on express those distinctive features of the soul and the city. Cephalus, we learn, has spent his life in the acquisitive arts. That is to say, he’s a businessman. He’s been concerned with satisfying the needs of his body and making money. He represents what will later be called in the Republic the appetitive part of the soul, the appetites. Polemarchus, whose name actually means “warlord.” Think of that. The warlord is preoccupied with questions of honor and loyalty. He tells us, to get a little bit ahead of ourselves, that justice is helping your friends and harming your enemies. He seems to represent what Plato or Socrates will later call the spirited part of the soul, something that we want to return to. Thrasymachus, a visiting sophist, seeks to teach and educate, anticipating what the Republic will call the rational soul, the rational part of the soul.

Each of these figures, in many ways, prefigure the relatively superior natures of those who come later in the dialogue. The two brothers, Glaucon and Adeimantus, whose exchange with Socrates occupies, for the most part, the rest of the dialogue from Book Two onward, the two brothers who, incidentally, are the brothers of Plato. I should say, to my knowledge, we know nothing more about Glaucon and Adeimantus from history, but Plato put them into his dialogue. They will always be remembered as the two brothers in the dialogue. Again, they seem to represent something quite different. Bear this in mind as you are reading the book, because it is easy to kind of forget who’s talking and what they represent. Adeimantus is, we will find, the kind of hedonistic and pleasure-seeking brother. Glaucon, whose name means something like “gleaming”, “shining,” is the fierce and war-like of the two brothers. Of course, there is the philosophically-minded Socrates. Again, each of them seems to represent, in a superior way, the key components of the human soul, the appetitive, the war-like or spirited, and the rational. Together, these figures form a kind of microcosm of humanity. Each of the participants in the dialogue represents one of the specific classes or groups that will eventually occupy the just city to which Plato or Socrates gives the name Kallipolis, the beautiful city. Alright?

In the five minutes or so that remain, let’s just talk for a moment about the first conversation with the head of the family, Cephalus. We don’t need to look at this at great length. You can, I’m sure in your sections, you might want to talk about the arguments a little more specifically that are used in these first three sets of conversations between Cephalus, Polemarchus, and Thrasymachus. The question, more importantly– the question, I don’t know that it’s more importantly, but the question that I want us to examine a little bit here in the time remaining is what, again, these characters represent. Cephalus, as his name implies, Cephalus. What does that mean? Do you know? Head, yes, Cephalus, head, the head of the household, but also clearly the claims of age, of tradition, of family.

At the beginning of the dialogue when Polemarchus brought his friends back to the house, we see the aged father, Cephalus. He is just returning from prayer. He has just returned from performing certain acts of ritual sacrifice. He greets Socrates, in many ways, as a long, lost friend. Perhaps you have had this experience yourself, always a slightly uncomfortable one. When you bring a group of your friends back to your house, you’re expecting to have a good time, and your grandparent is there and says, “Oh, it’s so good to see a bunch of young people. I want to talk with you.” It’s always a slightly uncomfortable moment, you might say. We all have experienced this kind of thing. Everybody knows it from either end. I’m not a grandparent, thank god. But I feel the same thing often when my son brings his friends, maybe that I’ve known for a long time. “Oh, how are you doing?” and they want to get away. Socrates does something rather abrupt. “Tell me, Cephalus, what’s it like to be so old?” “What is it like to be like you?” “Do you still feel the need for sex?” Can you imagine saying that to someone’s grandfather? It gives you a little idea of the character of Socrates. Cephalus is so happy. “Oh, thank god I’m past that,” he says. “Thank god I no longer feel this erotic desire. At my old age, I can spend my time–” “When I was a young man, that’s all I did. I was thinking about sex all the time and when I wasn’t thinking about that, I was making money. But now I’ve had my fill of both and I can spend my later years, the twilight of my life, turning to the things about the gods, performing sacrifices commanded by the gods.”

Why does Plato begin this way? Well, Cephalus is, as should be clear, the very embodiment of the conventional, in both senses of that term. He’s not a bad man, by any means. But he is a thoroughly unreflective one. In attacking Cephalus as he does, Socrates attacks the embodiment of conventional opinion, the Nomos supporting the city. Note the way Socrates manipulates the dialogue, the conversation. Cephalus says that the pious man, the just man practices justice by sacrificing to the gods. Socrates turns that into the statement that justice means paying your debts and returning what is owed to you. Cephalus, in an easygoing manner, agrees and then Socrates says, “What would you think about returning a weapon that you had borrowed from a friend or someone who was in a very depressed”–we might say a depressed “frame of mind. Would that be just? How do you explain that? Would you do that if justice means paying your debts and giving back to each what is owed?” At that moment, Cephalus excuses himself from the dialogue and says, rather abruptly, “I have to go out and continue my sacrifices in the garden.” Socrates, in other words, has broken the bond of tradition and traditional authority that holds the ancient city and the ancient family together. Cephalus is banished from the dialogue. Tradition is banished and we never hear another word about it for the next 400 or so pages. That’s the way Socrates begins this dialogue, or that’s the way Plato has Socrates begin it. We’ll look a little more at some of these in our class for next time and then move into the characters of Adeimantus and Glaucon. Anyway, start your reading. Continue your reading. Your sections are going on this week, so enjoy yourselves.

Republic Books III-IV

Polemarchus

Ancient Athens polis / Wikimedia Commons

I want to continue with the account of the various figures, various persons who populate, who inhabit this dialogue, and who they are, what they represent, and how they contribute to the argument and the structure of the work as a whole.

I talked about Cephalus, and Socrates’s treatment of Cephalus, the embodiment of convention, the embodiment of Athenian opinion in the way in which Socrates as it were chases Cephalus out of the dialogue, out of the conversation. We never hear from him again. And the speakers are able, presumably, to pursue the audacious arguments that will appear in the rest of the book without the oversight of the head of the household, the embodiment of conventional opinion.

And Socrates next pursues this discussion with the son of Cephalus, Polemarchus, the man who first had Socrates approached on the Piraeus. Polemarchus is described as the heir of the argument as well as the, to be sure, the heir of the family fortune. Polemarchus is what the Greeks would call a “gentlemen.” Let us just say he is a person willing to stand up for and defend his family and friends. I don’t mean necessarily by a “gentlemen” somebody who holds the door for others, or so on, but somebody who stands up for his family and friends in the way that he does.

Unlike his father however, Polemarchus shows himself concerned not just with the needs of the body as Cephalus represented, but Polemarchus is concerned to defend the honor and safety of the polis. He accepts the view that justice is giving to each what is owed, but he interprets this to mean that justice means doing good to your friends and harm to your enemies. Justice, we might say, is a kind of loyalty, it is a kind of loyalty that we feel to members of a family, to members of our team, to fellow students of a residential college, and the kind of loyalty we feel to a place like Yale as opposed to all other places. That is to say, Polemarchus understands justice as a kind of patriotic sentiment that citizens of one city or one polis feel for one another in opposition to all other places. Justice is devotion to one’s own. And one’s own is the good for Polemarchus. One’s own is the just.

But Socrates challenges Polemarchus on the grounds that loyalty to a group, any group, cannot be a virtue in itself, and he trips Polemarchus up with a very, in many ways, familiar Socratic argument “Do we ever make mistakes?” he asks Polemarchus. “Isn’t the distinction between friend and enemy based on a kind of knowledge, on a perception of who is your friend and who is your enemy? Have we ever mistaken a friend for enemy?” The answer seems to be, “Of course we have.” We all know people who we thought to be our friends but we found out that they were talking behind our backs, or that they were operating to deceive us in some way or another. Of course, it’s happened to everyone.

“So how can we say that justice means helping friends and harming enemies,” Socrates asks, “when we may not even be sure who our friends and our enemies really are? Why should citizens of one state, namely one’s own have any moral priority over the citizens of another state when, again, we don’t know them and we may well be mistaken in our assumption that they are enemies or friends? Isn’t, in other words such an unreflective attachment to one’s own bound to result in injustice to others? Socrates seems to be asking Polemarchus.

Once again, in many ways, we see Socrates dissolving the bonds of the familiar. At no other point in the Republic, I think, do we see so clearly the tension between philosophical reflectiveness on the one hand in the sense of camaraderie, mutuality and esprit de corps necessary for political life on the other. Socrates seems to dissolve those bonds of familiarity, loyalty and attachment that we all have by saying to Polemarchus, “How do we know, how do we really know the distinction between friend and enemy?”

But Polemarchus seems to believe that a city can survive only with a vivid sense of what it is. Of what we might say, what it stands for, and an equally vivid sense of what it is not, and who are its enemies. Isn’t this essential for the survival of any state, of any city? To know who its friends and enemies are? Who its challenges are? Socrates’s disillusion of that very framework, challenges, it seems to me, the very possibility of political life by questioning the question or the distinction between friend and enemy.

Although Polemarchus, like his father, is reduced to silence, it is notable that his argument is not defeated. Later in theRepublic you will see, not that much later even, Socrates will argue that the best city may be characterized by peace and harmony at home, but this will never be so for relations between states. This is why even the best city, even Kallipolis will require, as he spends a great deal of time discussing, will require a warrior class, a class of what he calls “auxiliaries.” War and the preparation for war is an intrinsic part of even the most just city. Even the Platonic just city will have to cultivate warrior citizens who are prepared to risk life in battle for the sake of their own city.

So in many ways, it seems that Polemarchus’ argument, while apparently refuted in Book I, is rehabilitated and re-emerges in its own way later in the dialogue. And we might want to think about this because it is an argument that is very important to contemporary twentieth century–important twentieth- century political theorist by the name of Schmitt who made the distinction between what he called the friend and the enemy, you remember, are central to his understanding of politics. This is an argument that comes from Polemarchus in Book I of the Republic.

Thrasymachus

Lady Justice statuette / Wikimedia Commons

Polemarchus is dispatched in one way or another, and this creates the opportunity for the longest and in many ways most memorable exchange in Book I, and perhaps even the Republic as a whole, the exchange with Thrasymachus who represents a far more difficult challenge in his own way than either of the first two speakers. In many ways, because Thrasymachus could be seen as Socrates’s alter-ego in some way, his sort of evil twin.

He is, how to put it? He is the Doctor Moriarty to Socrates’s Sherlock Holmes. You know, the evil doppelganger in some way.

Thrasymachus’ is a rival of Socrates in many respects; he also like Socrates is a teacher clearly. He is an educator. He claims to have a certain kind of knowledge of what justice is, and claims to be able to teach it to others. He is teaching a kind of, we will find out, a kind of hard-headed realism that expresses disgust at Polemarchus’ talk about loyalty and friendship and the like. “Justice,” he asserts, “is the interest of the stronger.” Every polity of which we know is based upon a distinction between the rulers and the ruled. Justice consists of the rules, that is to say, that are made by and for the benefits of the ruling class. Justice is nothing more or less right than what benefits the rulers, the rulers who determine the laws of justice.

Thrasymachus is, of course even for us today, a familiar kind of person. He is the intellectual who enjoys bringing, you might say, the harsh and unremitting facts about human nature to light, who enjoys dispelling illusions and pretty beliefs. He’s the one who probably would be the first to tell you there is no Santa Claus. He is that kind of hard-boiled realist.

No matter how much we may dislike him in some ways, one has to admit also there maybe a grain, if not more than a grain of truth in what he seems to be saying. And what he seems to be saying is this: we are beings who are first and foremost dominated by a desire for power. This is what distinguishes, you might say, the true man, the real man, the alpha male you might say, from the slave. Power and domination are all we truly care about. And when we get later in this semester to Thomas Hobbes, remember Thrasymachus. I’ll just say that for now. Remember Thrasymachus when we get to Hobbes. Power and domination are all we care about.

And what is true of individuals is also true for collective entities, collective nouns like states and cities. Every polity seeks its own advantage against others, making relations between states a condition of unremitting war of all against all. In the language, if I can switch to the language of modern economics, one could say that for Thrasymachus politics is a zero-sum game. There are winners and there are losers, and the more someone wins that means the more someone else will lose. And the rules of justice are simply the laws set up by the winners of the game to protect and to promote their own interests. It didn’t take Karl Marx to invent, or to discover that insight, that the rules of justice are simply the rules of the ruling class. That comes straight out of Thrasymachus, Book I of the Republic.

Well, how to respond? And again, Socrates challenges Thrasymachus with a variation of the argument that he used against Polemarchus. That is to say “Do we ever make mistakes?” That is to say, it is not self-evident, or it is not always intuitively obvious what our interests are. If justice is truly in the interests of the stronger, doesn’t that require some kind of knowledge, some kind of reflection on the part of those in power to know what is really and truly in their interest? People make mistakes and it is very possible to make a mistake about your own interests. And of course, Thrasymachus has to acknowledge this, of course the rulers make mistakes, and he tries to invent an argument that if a ruler makes a mistake, he’s not really a true ruler. The true ruler is the person who both acts on his own interest and of course knows what those interests are.

But the point that he admits is all, in a sense, that Socrates needs; justice is not power alone, justice requires knowledge. Justice requires reflection. And that is of course at the core of the famous Socratic thesis, that all virtue is a form of knowledge, all the virtues require knowledge and reflection at their basis.

But much of the exchange with Thrasymachus turns on the problem of what kind of knowledge justice involves, and justice is a kind of knowledge. If justice equals self-interest and self-interest requires knowledge, well what kind of knowledge is that? Thrasymachus contends that justice consists of the art of convincing people to obey the rules that are really in the interests of others, the interests of their rulers. Justice, in other words, for Thrasymachus is a kind of sucker’s game; obeying the rules that really benefit others largely because we fear the consequences of injustice. Justice is really something only respected by the weak who are fearful of the consequences of injustice.

Again, the true ruler, in some ways, is one, Thrasymachus believes, who has the courage to act unjustly for his own interest. “The true ruler,” he says “is one who is like a shepherd with a flock, but he rules not for the benefit of the flock but, of course, for his own interests, the good of the shepherd.” Justice, like all knowledge, is really a form, again, of self-interest.

And so one can ask, “Is Thrasymachus wrong to believe this?” And I realize I’m moving over this very quickly, but is Thrasymachus wrong to believe that?

Socrates wins the argument in Book I with a kind of, you might even say, sleight of hand. Both he and Thrasymachus believe that justice is a virtue, but Socrates says, “What kind of virtue is it to deceive and fleece other people?” Thrasymachus is forced to admit that the just person is a fool, Thrasymachus believes, is a fool for obeying laws that are not beneficial to him. But the best life, Thrasymachus believes, it doing maximum injustice to others, doing whatever you like. And with that realization, we see a very dramatic moment in Book I, even in the book as a whole. Thrasymachus blushes. He blushes when he realized that he has been defending the claim not that justice is a virtue, but that justice is something that is really a form of weakness. Thrasymachus himself seems to be embarrassed by his defense of the tyrannical life, of the unjust life.

The suggestion Plato seems to be making by making Thrasymachus blush is, despite all of his tough talk, that he’s not as tough as he appears to be, as he wants to think of himself to be. He’s shamed by the fact that he has been defending injustice and the tyrannical way of life. And so it appears, the three conversations end, Book I ends with uncertainty about what justice is. We have had three views of Cephalus, Polemarchus, and Thrasymachus. They have all been refuted, but no clear alternative seems to have emerged. Certainly Socrates has not really proposed an alternative to Thrasymachus in his exchange with him; he has only, as it were, forced Thrasymachus to see that the logic of his ideas, the logic of his argument that justice is in the interest of the stronger, is a defense of tyranny, and is a defense of the unjust way of life.

Glaucon

Gyges Ring illustration from Eric Thomas Weber

So all of Book I is really a kind of warm up for what follows in the rest of the book. We find out presumably what justice is. Until that point, we have no reason to really give up on our current existing ideas about what justice is. And this is where the two most important figures of the Republic begin to make their voices heard. Those are Glaucon and Adeimantus.

Glaucon tells Socrates that he is dissatisfied with the refutation of Thrasymachus, and so should we. Thrasymachus has been shamed, he has been forced to see where the logic of his argument takes him, but that is not the same thing as being refuted. Thrasymachus is really, as it turns out, a kind of girly-man who is ashamed to be seen defending the unjust life. “But why should we be ashamed to praise injustice?” Glaucon challenges Socrates. “It’s not enough to show that justice is wrong,” Glaucon says. “What we need is to hear why justice is good,” or more precisely to hear justice praised for itself. “Is there, in your opinion,” Glaucon asks Socrates, “a kind of good that we would choose because we delight in it for its own sake?” 358A. Is there a kind of good that we delight in for its own sake? And this is where the rubber hits the road.

Who is Glaucon? Glaucon and Adeimantus are the brothers of Plato, and other than their appearance in this book, there is no historical record left about them. But Plato has given us enough. In the first place, they are young aristocrats, and Glaucon’s desire to hear justice praised for its own sake indicates something about his scale of values. It would be vulgar, he believes, to speak of justice, or any virtue in terms of material rewards or consequences. He does not need to hear justice praised for its benefit, he’s indifferent to the consequences. Rather, he claims that he wants to hear justice defended the way that no one has ever defended it before. The brothers desire to hear justice praised for itself alone, and that seems to be expressive of their own freedom from mercenary motives and incentives. It reveals to us something about their idealism and a certain kind of loftiness of soul.

And certainly the brothers, we find out, are not slouches. They are not slouches at all. Although it is easy to remember that later in the dialogue most of their contribution seems to be of the form of “Yes Socrates, no Socrates,” they seem to be rather passive interlocutors. Their early challenges to Socrates show them to be potential philosophers. That is to say the kind of persons who might one day rule the city.

Of the two, Glaucon seems to be the superior. He is described as the most courageous, which in that context means the most manly, the most virile, and later Socrates admits that he has always been full of wonder at the nature of the two brothers. And at 368a, he cites a line of poetry, you’ll remember, written about them for their distinction in battle, they have been in war, they have been tested in war obviously.

They are also, and we see this from their relationship between one another, and the way they speak to one another, they are also highly competitive, super achievers. A little bit like some of you perhaps. There is quite a bit of jousting between them that you need to be attentive too. And each proposes to Socrates a test that he will have to pass in order to prove the value of justice and the just life.

Glaucon goes on to rehabilitate the argument of Thrasymachus in many ways, in a more vivid and a more expressive way than Thrasymachus did himself. Glaucon tells a story, you’ll remember, a story that he modifies from the historian Herodotus, a story about a man named Gyges who possessed a magic ring that conferred on him the power of invisibility.

Who has not wondered what we would do if we had this power, the power of invisibility? Gyges, in Glaucon’s retelling of the story, Gyges uses this ring to murder the king and to sleep with his wife, and to set himself up as king. What would you do if you had this power, the power of this magic ring, where you could commit any crime, indulge any vice, commit any outrage and be sure you could always get away with it? Why if you could do that would you wish to be just at the same time, or wish to be just instead of that? This is the challenge that Glaucon poses to Socrates. Why would someone with absolute power and complete immunity to punishment, why would they prefer justice to injustice? “Tell me that Socrates,” Glaucon asks. “If justice truly is something praiseworthy for itself alone, then Socrates should be able to provide an answer that will satisfy Glaucon’s retelling of the story of Gyges, that is certainly a very tall order.

Adeimantus

Wikimedia Commons illustration

And that is where the brother, Adeimantus, joins in. Adeimantus has a somewhat different set of concerns. He has heard justice praised his whole life from parents and from poets and from other authorities, but for the most part, he has only heard justice praised again for the benefits justice confers both in this life and the next. Honesty is the best policy, we’ve heard Cephalus being concerned about returning to others what you owe as a way of pleasing the gods in the afterlife, and Adeimantus rightly takes this kind of argument to mean that justice is simply a virtue for the weak, the lame and the unadventurous, if you were only concerned with the consequences. A real man does not fear the consequences of injustice. Rather, Adeimantus’ concern, and he gives a very revealing image of what he takes justice to be, is with an image of self-guardianship, or self-control. He tells us at 367a that each would be his own god. In other words, we should not care what people say about us, but we should be prepared to develop qualities of self-containment, autonomy and independence from the influence that others can exercise over us. “How can I develop those qualities of self-guardianship or self-control?” he asks Socrates.

And who has not felt that way before? The two brothers desire to hear justice praised for itself, Glaucon, and to live freely and independently, Adeimantus. And that shows to some degree I think, their own sense of alienation from their own society. Or if I can put the case for them slightly anachronistically, these are two sons of the upper bourgeois who feel degraded by the mendacity and hypocrisy of the world they see around them. And anyway, what person with any sensitivity to greatness has not felt this way at one time or another?

The two are open to persuasion, to consider alternatives, perhaps even radical alternatives, to the society that has nurtured them. They are, to put it another way perhaps, not only potential rulers and potential philosophers, they may also be potential revolutionaries, and the remainder of the book is addressed to them and of course people like them.

But the speeches of Glaucon and Adeimantus, you might say the circle around Socrates is effectively closed. He knows he will not be returning to Athens that evening, and he proposes to the two brothers and those listening to the conversation a kind of thought experiment that he hopes will work magic on the two. “Let us propose,” he says, “to watch a city coming into being in speech.” Let us create a city in speech. “It is easier,” he says, “not to view justice microscopically in an individual, but rather let’s view justice as it were through a magnifying glass.” Let’s view justice in the large sense. Let us view justice in a city in order to help us understand what it is in an individual.

And this idea that the city is essentially analogous to the soul, that the city is like the soul, is the central metaphor around which the entire Republic is constructed. It seems to be presented entirely innocuously, no one in the dialogue objects to it, yet everything else follows from this idea that the city, the polis, is in the central respect like an individual, like the soul of an individual.

What is Socrates trying to do here, and what is that metaphor, that central metaphor, what function does it serve within the work? To state the obvious, Socrates introduces this analogy to help the brothers better understand what justice is for an individual soul. The governance of the soul, Adeimantus’ standard of self-control, must be like the governance of a city in some decisive respects. But in what respects? How is a city like a soul and in what respect is self-governance, the control of one’s passions and appetites, in what respect is self-control like the governance of a collective body?

Consider the following example: when we say that so and so is typically American, or typically Taiwanese for example, we mean that that person expresses certain traits of character and behavior that are broadly representative in some way of the cross section of their countrymen. Is this a useful way to think? More specifically, what does it mean to say that an individual can be seen as magnified in his or her country, or that one’s country is simply the collective expression of certain individual traits of character? That seems to be what Socrates is suggesting. Right, that’s what he’s getting at.

One way of thinking about the metaphor of city and soul together is to think of it as a particular kind of causal hypothesis, about the formation of both individual character and political institutions. In this reading of the city/soul analogy as a kind of causal relation, maintains the view that as individuals we both shape and determine the character of our societies, and that those societies in term shape and determine individual character. The city and soul analogy could be seen then as an attempt to understand how societies reproduce themselves, and how they shape citizens who again in turn shape the societies in which they inhabit.

That seems to be one way of making sense of the city/soul hypothesis, but again it doesn’t seem to answer the question in what way are cities and individuals alike. To take the American case for example, does it mean that something like the presidency, the congress and the court can be discerned within the soul of every American citizen? That would be absurd to think that obviously. I mean, I think that would be absurd. Maybe you want to argue it and we could have a discussion, but it might mean that American democracy, or democracy of any kind, helps to produce a particular kind of democratic soul. Just like, you might say, the old regime in France, the old aristocratic society existing before the revolution, tended to produce a very different kind of soul, a very different kind of individual. Every regime will produce a distinctive kind of individual, and this individual will come to embody the dominant character traits of the particular regime.

The remainder of the Republic is, again, devoted to crafting the regime that will produce a distinctive kind of human character, and that of course is why the book is a utopia. There has never been a regime in history that was so single-mindedly devoted to the end of producing that rarest and most difficult species of humanity called simply philosopher.

So, city and soul. That leads to our next topic that I want to pursue for the remainder of the class, the reform of poetry and the arts.

Socrates’s city speech proceeds through several stages. The first stage proposed by Adeimantus is the simple city, what he calls the city of utmost necessity. That is a city limited to the satisfaction of certain basic needs. The primitive or simple city, the city of utmost necessity, again it expresses the nature of Adeimantus’ own soul, there is a kind of noble simplicity in him that treats subjects as bodies or creatures of limited appetites. The simple city is little more than a combination of households designed for the sake of securing one’s existence.

And at this point, and you can hear his brother chastising him, at this point Glaucon retorts that it seems as if Adeimantus has created a city only fit for pigs, a city of pigs. Are we only such that we want to feed at a common trough? Is there nothing more to politics than that? And Glaucon says, “Where are the luxuries? Where are the relishes,” he asks. “Where are the things that make up a city?” And hereto Glaucon’s city expresses his own tastes and his own soul. The war-like Glaucon would preside over what Socrates calls a feverish city, one that institutionalizes honors, competitions and above all war. If Adeimantus, again, expresses the appetitive part of the soul, Glaucon represents the quality that Plato calls spiritedness, or thumos in Greek.

Spiritedness and the Establishment of the Just City

SlideShare, Creative Commons

Spiritedness is the central, psychological quality of the Republic. The entire thrust of the book is devoted to the taming of spiritedness, and to the control of spiritedness. Spiritedness is that quality of soul that is most closely associated with the desires for honors, fame and prestige. It is a higher order psychological quality. It seeks distinction, the desire to be first in the race of life and lead us to seek to dominate others. We all know people of this sort, do we not? And we all to some degree embody this quality in ourselves. It is the quality that we associate with being a kind of alpha personality. This is the issue for Socrates, how to channel this wild and untamed passion of spirit or heart, how to channel this to some kind of common good. Can it be done? How can we begin the domestication of the spirited Glaucon? The rest of the book is to some degree about taming, asking the question whether Glaucon can be tamed.

And it is here that Socrates turns to his first and perhaps even his most controversial proposal for the establishment of the just city. “The creation of the just city can only begin,” he says, “with the control of music, poetry and the arts.” And this is where Plato’s image as an educator drives. The first order of business for the founder of a city, any city, is the oversight of education. And his proposals for the reform of poetry, especially Homeric poetry, represent clearly a radical departure from Greek educational practices and beliefs. Why is this so important for Socrates? Ask yourself, if you were founding a city, where would you begin?

Socrates’s argument seems to be something like this: it is from the poets and I mean that in the broadest sense of the term, myth makers, storytellers, artist, musicians, today we might say film and television producers, it is from these people that we receive our earliest and most vivid impressions of heroes and villains, gods and the afterlife. These stories, the stories we hear from earliest childhood on, shape us in some very meaningful sense for the rest of our lives. And the Homeric epics were of course for the Greeks what the Bible was for us. Maybe even is in some communities. The names of Achilles, Priam, Hector, Odysseus, Ajax, these would have been just as familiar and important to the contemporaries of Plato as the names of Abraham, Isaac, Joshua and Jesus are for us.

Plato’s critique of Homeric poetry in the Republic is two-fold; it is both theological and political. Maybe you might even say following Spinoza, that this is the core of Plato’s theological political treatise here. The theological critique is that Homer simply depicts the gods as false, as fickle, and inconstant. He presents them as beings who are unworthy of our worship. More importantly, the Homeric heroes are said to be bad role models for those who follow them, they are shown to be intemperate in sex, overly fond of money, into these vices Socrates adds cruelty and disregard for the dead bodies of one’s opponents. The Homeric heroes are ignorant and passionate men full of blind anger and desire for retribution. How could such figures possibly serve as good role models for citizens of a just city?

And Socrates’s answer is, of course, the predation of poetry and the arts in Books II and III. He wants to deprive poets of their power to enchant, and something Socrates admits in the tenth book of the Republic, to which he himself has been highly susceptible to the enchantment of the poets. We need to deprive, again, the poets, the song makers, the lyricists, the musicians, the mythmakers, the storytellers, all of them, the power to enchant us. And in place of the pedagogical power of poetry, Socrates proposes to install philosophy in its place. As a result, the poets will have to be expelled from this city. Imagine that. Sophocles will be expelled from the just city that Socrates wants to create.

This always raises the question that you will discuss in your section, whether or not Socrates’s censorship of poetry and the arts is an indication of his totalitarian impulses. This is the part of the Republic most likely to call up our own first amendment instincts. “Who are you, Socrates,” we are inclined to ask, “to tell us what we can read here and listen to?” And furthermore, Socrates seems to be saying not that the Kallipolis will have no poetry and music, it will simply be Socratic poetry and music.

And there’s another question which you would no doubt be concerned to discuss, namely what would such Socratically purified music and poetry look like? What would it sound like? I don’t know that I have an answer to this, but perhaps theRepublic as a whole is itself a piece of this Socratic poetry that will substitute for the Homeric kind.

But it’s important to remember that the question of education and the question of the reform and censorship and the control of poetry is introduced in the context of taming the war-like passions of Glaucon and others like him. The question of censorship and the telling of lies is introduced, in other words, as a question of military necessity, controlling the guards or the auxiliaries of the city, its warrior class.

Nothing is said here about the education of farmers, artisans, merchants, laborers, the economic class. Maybe, to speak bluntly, Socrates just doesn’t care that much about them. It’s okay what they listen too. Nor has anything really been said up to this point about the education of the philosopher. His interest here is in the creation of a tight, and highly disciplined cadre of young warriors who will protect the city much as watchdogs protect their own home. That is to say, recalling Polemarchus, those who are good to friends and bark and growl at strangers. Such individuals will subordinate their own desires and pleasures to the group, and live a life by a strict code of honor.

We have to ask: are Socrates’s proposals unrealistic? Are they undesirable? Or are they desirable? They are not undesirable if you believe as he does that even the best city must provide provisions for war, and therefore a warrior’s life, a soldier’s life, will require harsh privation in terms of material rewards and benefits as well as a willingness to sacrifice for others.

It would seem far from being unrealistic, Socrates engages what we might call maybe a kind of Socratic realism. Far more unrealistic would be the belief of those who argue, and I’m thinking here of names like Immanuel Kant and others from the eighteenth and nineteenth century, that one day we can abolish war altogether, and therefore abolish the passions that give rise to conflict and war. So far Plato believes, is a passionate or spirited aspect of nature remains strong so long will be necessary to educate the warriors of society who defend it.

So on that I’m going to end today and next time we will talk about justice, the philosophers and Plato’s discovery of America.

Republic Book V

The Control of Passions

I’m going to try to rush through, unfortunately, a number of the major themes regarding the creation of the just city, the creation of Kallipolis and then try to end the class by talking about, as I like to do for every thinker, what does in this case, what does Plato, what are his views on modern America. What does Plato say to us today?

But I want to start with what is one of the grand themes of the Republic, it is indicated in Book II by Adeimantus’ speech about self-control. It is introduced further by the claims of Socrates to control, to censor, to control the poetry and the arts of the city. And this is the big theme of what one might call “the control of the passions.” This is the theme of every great moralist from Spinoza to Kant to Freud. How do we control the passions? And it is certainly a large theme of Plato’s theory of justice in the Republic. Every great moral philosopher has a strategy for helping us submit our passions to some kind of control, to some kind of supervening moral power. And again, recall this is the theme raised at the beginning of Book II by Adeimantus, who puts forward an idea of self-control, or what he calls self-guardianship as his goal. How can we protect ourselves from the passion for injustice? And one of the things Socrates emphasizes is that the most powerful of those passions, the most powerful passion is that Socratic passion that he calls thumos, or what our translator has as spiritedness, anger, maybe what biblical translators call heart, having a big heart, having thumos and all of that implies. This is for Plato, the political passion par excellence. It is a kind of fiery love of fame, love of distinction that leads men and women of a certain type to pursue their ambitions in public life, in the public space. It is clearly connected this notion of spiritedness or this thumotic quality to our capacities for heroism and for self-sacrifice.

But it is also connected to our desires for domination and the desire to exercise tyranny over others. Thumos has a kind of dual component to it. It can lead us to a sense of kind of righteous indignation and anger at the sight of injustice, but it can also lead us in a rather contradictory way to desire to dominate and tyrannize over others. This is the quality that Socrates regards as being possessed by every great political leader and statesman, but it is also clearly a quality possessed by every tyrant. And the question posed by the Republic, in many ways, the question around which the book as a whole gravitates, is whether this thumotic quality can be controlled. Can it be re-directed, can it be re-channeled in the service of the public good? Socrates introduces the problem of thumos by a story, a particularly vivid story that I hope you all remember, where in Book IV he tells the story about Leontius at the walls.

“Leontius,” he writes, “was proceeding from the Piraeus outside the north wall when he perceived corpses lying near the public executioner. At the same time, he desired to see them. He wanted to see this grotesque sight, these dead bodies lying there. And to the contrary, he felt disgust and turned himself away and for a while he battled with himself and hid his face. But eventually overpowered by desire, he forced his eyes open and rushing towards the corpses said ‘see you damn wretches, take your fill of this beautiful sight'” 439c. That story that Socrates tells here is not one of reason controlling the passions, but rather one of intense internal conflict that Leontius felt. We see his conflicting emotions both to see and not to see, a sense that he wished to observe and yet he is at, in some ways, at war with himself, knowing to gawk, to stare at this sight. There’s something shameful about it and he felt shame. One example I particularly like of this was suggested last year, I think, by Justin Zaremby who said it’s the emotion we all feel when we’re driving down the highway, right, and we see a car crash or we go by a wreck and everybody slows down, right, they all want to see. What are they hoping to see? Well, they want to see blood, they want to see if there’s a body, they want to see how much damage has been caused. And we’ve all been in this, where we know that it’s shameful to look at this, just drive on, as Socrates would say “mind your own business,” and yet at the same time we feel, even against our will, compelled to look and think about that.

And think about that and this case of Leontius the next time you, for those of you who have driver’s licenses, are next driving on the highway and see something like that. It is the thumos that is the cause of–that should be the cause of your shame at slowing down to look. Sometimes we can’t help but slow down because everybody is slowed down in front of us, we have no choice. But anyway, that incident, that story that Socrates relates is connected to the fact that Leontius is a certain kind of man. He regards himself as proud, independent, someone who wants to be in control of his emotions but isn’t. He is a soul at war with himself, and potentially therefore, at war with others. And what the Republic tries to do is to offer us strategies, maybe we might even call it a therapy, for dealing with thumos, for submitting it to the control of reason and helping us to achieve some level of balance, of self-control and moderation. And these are the qualities taken together that Socrates calls justice, that can only be achieved when reason is in control of the appetites and desires. Again, a question the book asks is whether that ideal of justice can be used as a model for politics. Can it serve as a model for justice in the city?

This connection he has established between justice in the city and justice in the soul, what are the therapies or strategies for solving injustice in the soul or imbalance of some kind in the soul? Can those be transferred or translated in some way to public justice, to political justice, justice in the polis? Right? You with me on that so far?

A Proposal for the Construction of Kallipolis

So, on the basis of this, Socrates proposes how to proceed with the construction of Kallipolis, and he does so through what he calls three waves. There are three waves, three waves of reform, so to speak, that will contribute to the creation of the city. The first of these waves is, you remember, the restrictions on private property, even the abolition of private property. The second, the abolition of the family, and the third wave being the establishment of the philosopher kings. Each of these waves is regarded as in some way necessary for the proper construction of a just city. And I’m not going to speak about all of them, but I do want to speak a little bit about, because it has particular relevance for us, his proposals for the co-education of men and women that is a great part of his plan, especially related to the abolition of the family, that men and women be educated in the same way, right.

The core of Socrates’s proposal for equal education is presented in a context that he knows to be or suggests will be laughable. It will certainly be seen that way, he suggests, by Glaucon and Adeimantus. There is no job, he states, that cannot be performed equally well by both men and women. Is Socrates a feminist? Gender differences, he says, are no more relevant when it comes to positions of political rule than is the distinction between being bald and being hairy. Socrates is not saying that men and women are the same in every respect, he says, but equal with respect to competing for any job at all. There will be no glass ceilings in Kallipolis. The first, in many ways, great defender, the first great champion of the emancipation of women from the household. But this proposal comes at certain costs, he tells us. The proposal for a level playing field demands, of course, equal education.

And here he says that men and women, being submitted to the same regime, will mean, among other things, that they will compete with one another in co-educational gymnasia. They will compete with each other in the nude because that is the way Greeks exercised. They will compete naked in co-educational gymnasia, think of that. Furthermore, their marriages and their procreations will be, he tells us, for the sake of the city. There is nothing like romantic love among the members of the guardian class. Sexual relations will be intended purely for the sake of reproduction and unwanted fetuses will be aborted. The only exception to this prohibition is for members of the guardian class who are beyond the age of reproduction, he tells us, and they, he says, can have sex if they’re still able, with anyone they like. A kind of version of recreational sex as a reward for a lifetime of self-control. Child-bearing may be inevitable for women but the rearing of the child will be the responsibility of the community or at least a class of guardians and common daycare centers. A sort of variation of Hillary Clinton’s book that “it takes a village to raise a child,” comes right out of Plato apparently. No child should know their biological parents and no parent should know their child. The purpose of this scheme being to eliminate senses of mine and me, to promote a kind of common sense of esprit de corps among the members of the guardian class, “a community of pleasure and pain,” Socrates calls it at 464a. What we are creating is a community of pleasure and pain. I will feel your pains, and of course you will feel mine.

The objections to Socrates, are of course, you know, raised as early as by Aristotle himself, in the very next generation. How can we care for things, how can we truly care for things that are common? We learn to care for things that are closest to us, that are in some way our own. We can only show proper love and concern for things that are ours, not things that are common. Common ownership, Aristotle argues, will mean a sort of common neglect. Children will not be raised better by putting them under the common care of guardians or in daycares but they will be equally neglected. But it is in this, and you can think about that, about whether that’s true or not, but it is in the same context of his treatment of men and women that something else often goes unnoticed and that is Socrates’s efforts to rewrite the laws of war, because of course the guardians are being trained and educated to be guards, to be warriors, to be members of a military class.

In the first place, he tells us, children must be taught the art of war. This must be the beginning of their education, Socrates says, making the children spectators of war. Children will be taken, he seems to suggest, to battles and to sites of where fighting is going on, to be spectators for them to become used to and habituated to seeing war and what everything that goes on. Not only is expulsion from the ranks of the guardians penalty for cowardice, but Socrates suggests there should be, listen to this, “erotic rewards for those who excel in bravery.” Erotic rewards for excellence in bravery. Consider the following remarkable proposal at 468c, “and I add to the laws of war,” Socrates writes, “that as long as they, the guardians, are on campaign, no one whom he wants to kiss should be permitted to refuse. So that if a man happens to love someone, either male of female, he would be more eager to win the rewards of valor.” That is to say as a reward for bravery, exhibited bravery, the hero should be allowed to kiss anyone they like while they are on patrol, male or female. A particularly puritanical editor of Plato from the twentieth century writes in a footnote to that passage, “this is almost the only passage in Plato that one would wish to blot out,” his sensibilities were offended by this notion. But I wonder what kind of, if this might even make a powerful incentive for military recruitment today. What do you think? Well, think about it. I don’t know.

Justice

So, at long last, we move from the education of the guards to justice. What is justice, we’ve been questioning asking ourselves throughout this book in which Plato has been, Socrates has been teasing us with. At long last we come to this thing. The platonic idea of justice concerns harmony, he tells us, both harmony in the city and harmony in the soul. We learn that the two are actually homologous in some way. Justice is defined as what binds the city together and makes it one. Or he puts it another way, consists of everyone and everything performing those functions for which they are best equipped. Each of the other citizens, Socrates says, must be brought to that which naturally suits him, which naturally suits him, one man, one job, he says. So that each man practicing his own which is one, will not become many but one. Thus you see, he says, the whole city will naturally grow up together.

Justice seems to mean adhering to the principal, justice in the city, adhering to the principal of division of labor. One man, one job, everyone doing or performing the task that naturally fits or suits them. One can, of course, as you’ve already imagined, raise several objections to this view and again Aristotle seems to take the lead. Plato’s excessive emphasis on unity would seem to destroy the natural diversity of human beings that make up a city. Is there one and only one thing that each person does best? And if so, who could decide this? Would such a plan of justice not be overly coercive in forcing people into predefined social roles? Shouldn’t individuals be free to choose for themselves their own plans of life wherever it may take them? But however that may be, Plato believes he has found in the formula of one man, one job, a certain foundation for political justice. That is to say, the three parts of the cities, workers, auxiliaries, guardians, each of them all work together and each by minding their own business, that is doing their own job, out of this a certain kind of peace and harmony will prevail. And since the city, you remember, is simply the soul at large, the three classes of the city merely express the three parts of the soul.