Assessing a group of early Carolingian grammar miscellanies using methods of digital network analysis.

By Dr. Elizabeth P. Archibald

Visiting Professor in Medieval History

University of Pittsburgh

Early medieval masters who faced the task of assembling intro-ductory materials for their students often described their mission as a sort of raid in the forests and fields of the ancients. The Anglosaxon missionary and grammarian Boniface described the process of compiling a grammatical manual as akin to entering “the ancient tangled forest of the grammarians in order to collect for you the best kinds of various fruits and the diffused perfumes of flowers for you, which are found scattered throughout the glades of the grammarians.”1 In the next generation, Alcuin addressed Charlemagne with a poetic description of rising early and “running through the fields of the ancients to pluck flowers in order to provide exercises of correct language for the boys.”2 These literary tropes, while somewhat overdramatic, accord with the more mundane relics of early medieval pedagogical activities.

The bouquets — florilegia — that resulted from masters scampering through the landscapes of the ancient grammarians are particularly characteristic of Carolingian literary culture broadly and schoolbooks specifically.3 Anyone who has had occasion to work with early medieval manuscripts, and schoolbooks in particular, has encountered catalogues identify-ing codices as “miscellany” and “florilegium.” These compilations abound in the liberal arts subjects, especially the trivium. There are several reasons for this phenomenon. Introductory texts tend to be short, lending themselves to shared-living arrangements in medieval codices, where parchment space is of course highly valuable. On the other hand, there is plenty of evidence that the compilers of manuscript miscellanies of the early Middle Ages produced their materials deliberately. Even when working with longer texts, they engaged in activities of excerpting, manipulating, and recombining to create useful compendia.4 This phenomenon highlights the role of miscellanies as handy collections and, more specifically, points toward an important feature of early medieval schoolbooks: they generally pertain more to the instructor than to the student. In other words, it is often clear that they are collections of material compiled by a particular master, in a particular educational context, for particular instructional exigencies.5 As such, they hold both promise and problems. I assess a group of early Carolingian grammar miscellanies using methods of digital network analysis, revealing both standardization and originality shaping this corpus of materials.

Early medieval miscellanies are an extremely valuable body of material, offering clues about what their compilers found useful; they are also quite numerous. Unfortunately, a millennium removed from these contexts, their logic is not always evident. Recent research has begun to recognize and interrogate the significance of early medieval miscellanies, but much work remains to be done.6 This work has been slow to unfold in part because, while miscellanies are both significant and abundant records of intellectual priorities, they are difficult to manage bibliographically. The miscellaneous character of early school-books was a challenge to medieval catalogers as well as modern, a phenomenon reflected in the earliest library catalogues, such as that of St. Gall. Some texts occupy codices in tidy fashion: “De doctrina Christiana in one codex.”7 Then, when the unfortunate medieval cataloger arrives at the section of codices with grammatical content, we find “Item, the two artes of Donatus, and Honoratus, De finalibus litteris, and declensions, and the commentary of Sergius on Donatus, and the book of Isidore, and the book of Caper on orthography, and the De metrica arte of Bede. All these things in one codex.”8

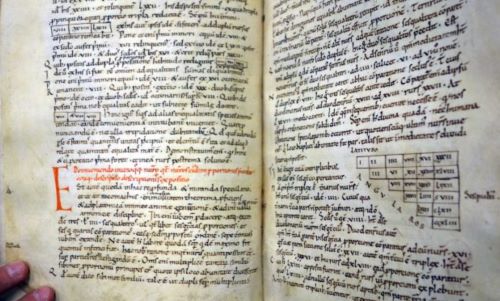

In fact, even this unwieldy description is deceptively tidy. The phrase “all these things in one codex” suggests that the relationship between codex and text is that of container and contents; the miscellaneous codex functions as a sort of receptacle for texts (“all these things”). But modern judgments about texts can be problematic: in the absence of a contemporaneous catalogue like this one, it is not always easy to understand what a compiler or scribe or user of a miscellany saw as a discrete text, especially when they flow together in a codex without rubrication or interruption. And, of course, making a determination about whether a particular document is a witness to a particular work is the fundamental first step in investigating the manuscript tradition of a work. But with miscellanies like these, where each manuscript represents a different approach to excerpting, adapting, interpolating, and recombining materials, it is often surprisingly difficult. There is such variety among the manuscripts that traditional approaches to text editing quickly become problematic.

This is a particularly difficult problem in the case of school-books, where even material that began its curricular life as a well-organized text might end up excerpted and incorporated into different compilations by different masters, with each of the compilations subject to the same kind of manipulations over time. By the Carolingian period, masters and compilers had been raiding the forests of the ancient grammarians for centuries, with constantly changing shopping lists. The typical situation is captured by a description of the Ars Ambianensis: “Even where all the versions are extant, none is identical to any other. They all reflect a putative original which each has adapted.”9 In some cases it is possible that the florilegia we are observing are the residue of textual practices that are difficult to trace: some of the innumerable short texts that appear in schoolbooks likely originated as schedulae — unbound scraps of parchment that were by-products of book production. Like wax tablets, few schedulae survive due to their ephemeral nature, but their use (including as substrate for first drafts of teaching materials) is documented, and some compilations may reflect transit of schedulae from one master to another in addition to the direct copying and excerpting of other codices.

As is often observed, a modern editor offering emendations and interventions designed to reconstruct authorial intention may be reverse-engineering a fantasy text.10 The miscellanies in question pose a similar problem: in trying to remove the flowers from the florilegium, a modern editor risks imposing anachronistic or inauthentic textual boundaries. The distinction between text and manuscript is evasive: is the thing in our hands a schoolbook in the sense of a canon of material, or a schoolbook in the sense of a physical object?

This problem is mitigated if we focus on the physical object, considering each codex as a self-contained intellectual universe. We can scrutinize a particular manuscript and consider its implications as a material representation of intellectual activity in a particular time and place. A number of schoolbooks have been productively considered in this way — usually those that can be securely attributed to a particular institution, often during the tenure of an important individual.11 Paleography-based study of manuscript groups tentatively associated with specific institutions, too, is a venerable and indispensable approach that has, over the years, produced much of what we know about institutions of learning in the early Middle Ages. Yet securely dat-ing and localizing manuscripts is an imperfect art: places are intuited from paleographical features, but scribes (and books) traveled, and it is the rare scribe considerate enough to provide precise dates; there is nearly always some uncertainty. Furthermore, scholarship gravitates toward the datable and localizable, while manuscripts of truly uncertain date and location tend to be overlooked altogether.

The larger problem, though, is this: an early medieval schoolbook, while highly individualized, is decidedly not a self-contained intellectual universe, and if we focus on one manuscript, as their idiosyncrasies push us to do, we miss the opportunity to examine the connections among these intellectual objects. We know that masters shared materials, but there is not as much direct evidence of these practices as we would like — and this is the major obstacle to a robust understanding of educational practices across Europe at a moment when these very manu-scripts suggest that education had a singularly important role in society.

Thus, there are two fundamental obstacles to using schoolbooks as evidence for early medieval educational practices. Miscellanies, the most characteristic materials of literary and pedagogical culture in the Carolingian period, do not yield easily to traditional textual approaches; this makes it difficult to assess the process of canon formation. Manuscripts of uncertain or unknown provenance restrict our ability to draw broad conclusions about shared educational culture and practices. A potentially fruitful angle of approach to both of the problems posed by these materials involves assessing schoolbooks as elements in a network of learning. This approach allows us to form an impression of the intellectual landscape of the curriculum and the circulation and sharing of curricular content, without needing precise information about particular schoolbooks and their affiliations with masters and institutions.

When it comes to visualizing relationships between manu-scripts, medievalists are accustomed to thinking in terms of the stemma, which reconstructs filiation relationships between textual witnesses, branching forth over time. In recent years, scholars have experimented with phylogenetic software (at first, software designed for analysis of evolutionary biology, and more recently, customized software for stemmatology) to assist efforts at reconstructing and visualizing relationships between manu-scripts. These efforts have been promising with two important caveats: first, as with any computer-assisted analysis, one should be aware of the assumptions the algorithm applies (e.g., does it admit the possibility of more than two manuscripts having been copied from one exemplar?), and second, one should use it appropriately, as an aid to identifying fruitful areas for further investigation (e.g., highlighting a manuscript of late date whose text is an early witness we might otherwise overlook).12

But the quirks of miscellanies, and didactic miscellanies in particular, mean that this corpus lends itself to a different type of analysis, focusing not on texts that change over time but on roughly contemporaneous materials that share content with each other as elements of a network. Network analysis is generally used to analyze the relationships between individuals or communities — correspondents exchanging letters, sites linked by roads, and disease victims connected by disease vectors. But it can help to elucidate any type of data involving a group of entities in relationship with one another — and that is what these miscellanies represent.13 Miscellanies can be seen as groups of texts in relationship with one another by virtue of existing in the same codex, where they could be encountered together by the same reader. On a larger scale, the manuscripts can be seen as existing in relationship with one another by virtue of containing the same text. Both of these types of relationship can be fruitfully examined with tools of network analysis. Such analysis does not offer a means of access to the masters and students who used these materials, but visualizing the relationships between schoolbooks and instructional materials as intellectual elements in a network offers a broad impression of how knowledge was shared and helps to render these problematic sources more trac-table. In other words, considering their connections within a wider network gives us a sense of the roads, even if the travelers remain unknown. This approach makes a virtue of the fact that miscellanies are so dynamic: they may vary so much that the distinction between text and manuscript becomes problematic and traditional editing tools cannot represent their complexity, but this variation also allows us to discern the shapes of curricula more clearly and helps to clarify the relationships between the materials.

In what follows, I will suggest some possibilities of two different network analysis approaches to a larger group of early Carolingian schoolbooks. The first analysis seeks to reveal the “communities of texts” within these miscellanies, providing a sense of the contours of the curriculum and a pedagogical canon in formation. The second approach examines affinities between manuscripts and groups of manuscripts based on their shared textual material, suggesting a way to think about intellectual networks that does not directly depend on data about text copying or assumptions about each manuscript’s institutional or geographic origin.

Both analyses take as a starting point the group of manu-scripts described by Bernhard Bischoff as “grammatical manuscripts from the age of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious.”14 Revealingly, although Bischoff sought to identify not miscellanies in particular but grammatical manuscripts in general, of the twenty-seven surviving manuscripts in Bischoff ’s list, all but one are miscellanies, containing between a handful and thirty-five or so texts and excerpts (depending, of course, on how one makes a determination about what constitutes a text), primarily but not exclusively dealing with grammar. For the purposes of this project, I have considered only miscellanies where evidence is strong that they existed as a compilation by the ninth century. The goal of the first analysis is to measure and visualize the clusters of texts that appear within the manuscript compilations. In other words, while no two codices among the group contain exactly the same menu of texts, there are groups of texts within that circulate together with greater frequency, and these appear as clusters within a larger network. To some extent, of course, it is possible to identify clusters like these without the assistance of software — such work has been done with some of the manuscripts in this corpus15 — but even in this relatively manageable group of manuscripts, the dataset consists of more than two thousand relationships between texts, and thus even exhausting manual study of the materials cannot reveal all of the patterns within.

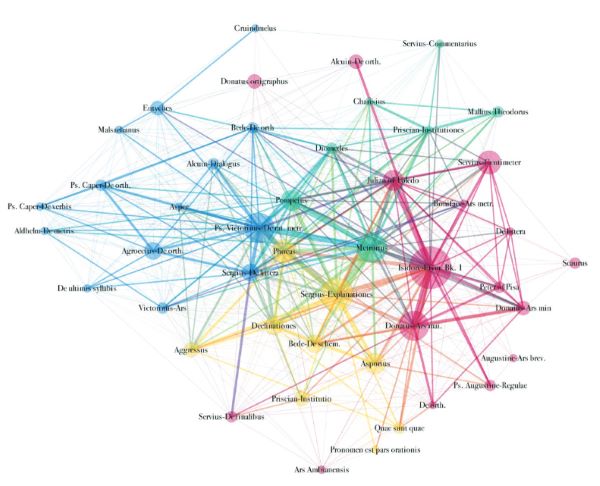

In the first network analysis, I have assigned the texts the role of “nodes,” conceptualizing them as elements in relation-ship with one another by virtue of circulating in the same manuscript. The manuscripts thus serve as the connections between different texts and are assigned the function of “edges” in the network. In effect, we are examining intellectual affinities — the edges represent connections between texts, reflecting the frequency with which Carolingian masters chose to collect specific materials together in a single compilation and Carolingian students and readers encountered them in this way.

Figure 1 is a graph of relationships between texts, created using the network visualization software Gephi. Each node represents a text. Texts appearing more frequently among the group of manuscripts appear as larger nodes. The edges drawn between nodes indicate that the texts represented by these nodes appear together within the same manuscript in at least one manuscript. The weight of each edge (represented visually as its width) is determined by the number of the manuscripts (within this set) in which the two texts appear together. The wider edges thus indicate that the two linked texts circulated more frequently in one another’s company. The layout of the graph has been generated using Gephi’s ForceAtlas2 algorithm, which causes linked nodes to be drawn toward one another, and non-linked nodes to be pushed apart. (This means that, in general, the more highly connected texts appear more central.) I have used Gephi’s modularity function to sort the nodes, allowing the algorithm to identify clusters of texts that circulate together with disproportionate frequency and on this basis establish communities within the larger network. Each of the clusters identified by Gephi’s modularity algorithm has been assigned a different color in this graph. For greater visual clarity I have excluded the texts that appear in a single manuscript in this group. What emerges through this process is a way of visualizing the early Carolingian grammatical curriculum.

Several features are immediately clear. This process trims away much of the “noise” in the schoolbooks since texts that appear in only one manuscript are excluded. Given the personalized nature of the schoolbooks, these are the majority, so the items that remain really do represent the core of the elementary grammar curriculum as it appears in these manuscripts. Unsurprisingly, Donatus (especially the Ars maior) appears rather prominent in the network — and closely connected with Isidore’s Etymologies, since they often circulated together. Although the shift of intellectual energy toward Priscian’s Institutiones over the course of the ninth century has occupied more attention in the educational history of the Carolingian period, these manuscripts show the importance of Donatus, especially at the introductory level of the curriculum that these compilations represent. Many of the manuscripts seem to be organized around the Ars minor and (especially) Ars maior, supplementing them with other useful materials. Priscian’s monumental Institutiones is an insignificant piece of the network, though it appears in numerous manuscripts on its own (especially in the second half of the ninth century). When we see the curriculum in a statistically grounded visualization, certain elements may come as a surprise: we might not immediately cite Isidore as the obvious authority on grammar, but Carolingian masters clearly depended on excerpts from the first book of the Etymologies in the elementary phase of the grammar curriculum; similarly, the rather mysterious Sergius (both De littera and Explanationes) was a clear favorite in grammar pedagogy.16

Although the manuscripts, examined in isolation, rarely appear highly planned, several groups of material emerge within the visualization that suggest patterns of organization and delineate comprehensible subject curricula. For instance, it is easy to identify a group of materials on orthography. The fifth-century Ars de orthographia of Agroecius is organized as a supplement to the De orthographia and De verbis dubiis, both attributed to (and neither authentically the work of ) the second-century scholar Flavius Caper.17 Not surprisingly, it circulates frequently with these texts. These texts also circulate disproportionately frequently with Bede’s orthographical work. While it is perhaps not surprising for texts on a common subject to appear as a curriculum, this is an interesting result for two reasons: first, it reveals some order within manuscripts that seem rather chaotic on their own, and second, it implies that scribes and compilers who could have chosen one favorite orthography manual from among the available options chose instead to collect several in one place (otherwise these texts would appear more closely linked with other materials). For orthography, then, some of the manuscripts seem to have functioned more as reference manuals than carefully curated pedagogical handbooks. An exception is Alcuin’s orthographical manual, which appears more closely connected with other texts: perhaps it superseded the others in the minds of some compilers.

Another link that emerges in this visualization is the frequency of cohabitation between “Metrorius” and Pseudo-Victorinus’s De ratione metrorum, two texts that have been noted as part of a collection of works often appearing together.18 The network visualization here shows texts in affinity without indicating the larger causes, and here we have already seen several potential reasons for texts to cluster together. In some cases, it appears that texts circulate together due to manuscript traditions: that is, they coalesced as a cluster prior to the copying of an individual manuscript and thus can be seen as more of a discrete compilation than a group of texts; this is the case with “Agroecius”/“Caper” and “Metrorius”/“Victorinus.” If texts were placed together at the moment of the manuscript’s copying, other explanations abound: they deal with the same material, and compiler(s) found it useful to gather multiple treatments of the same topics in one place; they deal with different materials, and compiler(s) thought they formed a useful curriculum; they share a geographical context (as is the case with, say, Quae sunt quae and Aggressus quidam19); they share origins as new com-positions rather than ancient texts. In other words, the network serves to highlight interesting features of the curriculum, for which we can settle on possible historical explanations.

One of the most interesting clusters that emerges in this vi-sualization is the group to which Donatus is assigned, which also includes Isidore of Seville (a variety of excerpts from book I of the Etymologies that can be broadly categorized as the Ars Isidori, as Evina Steinová discusses in this volume) and an anonymous commentary indicated as “De littera.” This material forms a rather comprehensive core of basic instruction about the letters of the alphabet and the parts of speech. The grammar of Peter of Pisa (identified by Einhard as Charlemagne’s own grammar teacher) is also assigned to this cluster. With this posited micro-curriculum identified, we can return to the manuscripts for additional information; among those that share this cluster in common are several important manuscripts from ca. 800 with a variety of connections to the court of Charlemagne. Perhaps the fact that these texts are closely linked lends support to the hypothesis that several of these manuscripts reflect the pedagogical interests of the court.20 Although direct evidence for links between manuscripts in this network is less plentiful than we might like, the larger visualization gives a good sense of curricular clusters. Returning subsequently to the manuscripts with a better grasp of the organization of the curriculum may allow for a more thorough assessment of how some groups of material were localized in particular regions and others shared widely — especially having established the larger network as a kind of baseline or control against which to measure the significance of a particular curriculum.

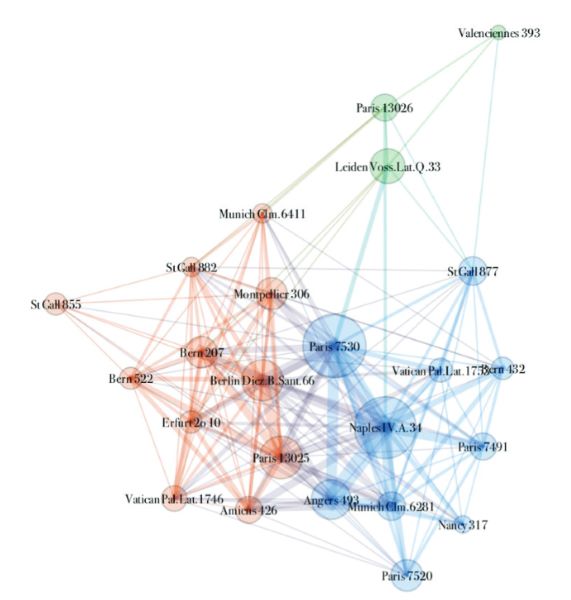

Having identified some of the intellectual relationships between the texts in these miscellanies as curricula or components of an educational canon, a second network analysis approach to the same materials offers another tool that helps to assess the shared intellectual preoccupations of the manuscripts. Like Figure 1, Figure 2 has been created using Gephi and its ForceAtlas2 algorithm. In this visualization, each manuscript is represented as a node, and the texts they share function as the edges connecting them. By considering the manuscripts themselves as nodes in a network that are in relationship with other manuscripts by virtue of their common texts (the same approach applied earlier to visualize the intellectual affinities between a small group of manuscripts), we can enrich our understanding of the intellectual network that includes these materials. While identifying intellectual affinities on the basis of shared material in manuscripts is an exercise that does not automatically necessitate the use of network-analysis tools, once again even in what appears to be a relatively manageable body of material (twenty-seven manuscripts), the connections of this type number well over a thousand, and thus the big picture is difficult to formulate without the assistance of software. Again, the edges do not represent evidence for direct contact between manuscripts as material objects but family affinities via shared materials; that is, the connections are intellectual rather than physical.

What emerges in figure 2, then, is a starting point for additional research on these manuscripts. Do closely linked manu-scripts share common geographical origins of which we are aware? For the most part they do not, although there are a few exceptions: Amiens 426 and Paris lat. 13025, for instance, positioned close together, are thought to be Corbie manuscripts. On the other hand, we might expect an opposite phenomenon, where manuscripts of common origin do not share many texts, since that would mean redundancies in institutional collections. If geographical origins do not correlate with textual preoccupations, is there evidence of a broadly shared curriculum across wide regions? Are textual affinities between manuscripts the result of a deliberate program, or of masters independently adopt-ing the same texts? These are central questions to the problem of understanding the way that Carolingian education functioned at local levels. Though this network visualization does not offer easy answers, it offers suggestions for fruitful areas of research.

One observation that can be made on the basis of this group of miscellanies is that compilers of grammatical material were highly independent. Many of the texts (more than eighty of them — or around 60 percent) are not shared with other manu-scripts in this group. When we look at shared texts, the numbers drop precipitously. The texts that appear in nine or more manuscripts thus represent a real curricular commitment within this group of manuscripts — excerpts from Isidore’s Etymologies, the Explanationes of Sergius, and Donatus’s Ars maior being the greatest hits of grammar in the age of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious on the basis of this group. But what compilers did with this common core of material — namely, supplement them with many other, much less popular, texts — seems to have been very much a matter of institutional or individual discretion.

So, while these manuscript miscellanies are complicated in ways that traditional editing tools find difficult to maneuver, their complications are actually of use in understanding them as pieces of a larger intellectual network. In other words, the changing menus of texts in this corpus can function as a sort of larger version of variants within a text, offering useful information about the way that individual masters and scribes worked curricular materials for their own uses. The clusters that emerge in each network analysis have a multiplicity of causes (whether common geographical origins for a group of manuscripts or deliberately selected thematic clusters of texts on a common curriculum), but they suggest broadly the way that these materials — schoolbooks in the sense of both texts and manuscripts — functioned in a wider intellectual network rather than as self-contained intellectual worlds. At the same time, it should be observed that the overall impression of variety and complexity within Carolingian schoolbooks is significant: it is difficult to discern the intellectual networks to which these materials belong precisely because masters felt free to compile ad hoc collections rather than (as is the old stereotype) copy-ing their ancient sources uncritically.21 Furthermore, the Carolingian reputation for standardization in other spheres has inspired searches for an “official” liberal arts curriculum, but the manuscripts are so varied that these searches have been mostly in vain.22 Against this backdrop, the curricular and manuscript clusters that emerge in the network analyses here are perhaps especially significant — suggesting that the miscellanies are not evidence of curricular chaos but efforts at making common materials locally useful.

The possibilities of examining these miscellanies and similar categories of evidence in the form of an intellectual network are many: here we see just some of the possible angles of investigation. This technique should be seen as complementary to other, more established approaches, which I have mostly avoided applying in this project in order to assess the utility of the network analyses and visualizations without relying on inferences from other sources. We can localize and date manuscripts and determine their roles in an intellectual network via scrutiny of all sorts of paleographical, codicological, and extra-textual clues, but a network analysis of this sort is complementary to these approaches, suggesting the broad contours of an intellectual landscape. And, like most techniques of digital analysis involving “big data,” it allows us to return to the manuscripts with a more precise sense of which threads to pull. Texts that appear unexpectedly as clusters may represent an effort to standardize the curriculum on a particular topic. Manuscripts that seem unexpectedly connected in the network may suggest promising avenues of research (such as St. Gallen Stiftsbibliothek 877, which contains a number of medical texts but which is highly connected with several very important early Carolingian grammatical manuscripts). Furthermore, such analyses could be deployed with other corpora: all sorts of manuscript miscellanies might benefit from this approach (letter collections, legal collections) as well as other types of material (one example is medieval library catalogues, which could be analyzed in this way to assess broad patterns within the intellectual landscape). Although these are preliminary experiments, they suggest the value of adding network visualization to the toolbox of research on medieval manuscripts, schoolbooks, and intellectual worlds.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Boniface, Praefatio ad Sigibertum. See Vivien Law, “An Early Medieval Grammarian on Grammar: Wynfreth-Boniface and the Praefatio ad Sigibertum,” in Grammar and Grammarians in the Early Middle Ages (London: Longman, 1997), 170.15–20: “tale tricationum molestarum onus […] ut anti-quam perplexae sylvam densitatis grammaticorum ingrederer ad colligendum tibi diversorum optima quaeque genera pomorum et variorum odoramenta florum diffusa, quae passim dispersa per saltum grammaticorum inveniuntur.” I owe thanks to a number of individuals for their help navigating the tangled forests of medieval manuscripts and network analysis, especially interlocutors at the Networks and Neighbours conference where this work was first presented in Nijmegen in 2017, members of the Carnegie Mellon University Digital Humanities Faculty Research Group, and the reviewers of this essay.

- Ernst Dümmler, ed., Monumenta Germaniae historica, Poetae Latini 1 (Berlin: Weidmann, 1881), 254 (carm. xlii): “in campos veterum procurrens carpere flores / rectiloquos ludos pangeret ut pueris.”

- The distinctive prevalence of such compilations in Carolingian literary culture was emphasized early on by M.L.W. Laistner, Thought and Letters in Western Europe, AD 500 to 900 (London: Methuen, 1957), 176: “One important product of monastic industry and of preoccupation with grammatica calls for brief notice. There were obvious advantages, both for use in the schoolroom and for private reading by those whose scholarship was limited, in chrestomathies.” On the strategies of grammar instruction in the Carolingian period, see Vivien Law, “The Study of Grammar,” in Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation, ed. Rosamond McKitterick (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 88–110.

- The understanding of these processes of knowledge selection underlying early medieval instructional materials continues to develop. Context for understanding the educational goals and practices that informed these materials is found in John J. Contreni, “Learning for God: Education in the Carolingian Age,” The Journal of Medieval Latin 24 (2014): 89–129. Foundational insights into the dynamics of the relationship between Carolingian manuscripts and educational contexts appear in Bernhard Bischoff, “Libraries and Schools in the Carolingian Revival of Learning,” in Manuscripts and Libraries in the Age of Charlemagne, trans. Michael Gorman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 93–114; Rosamond McKitterick, The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987 (London and New York: Longman, 1983), 200–228; as well as in studies of particular manuscript traditions, such as that of Donatus — Louis Holtz, Donat et la tradition de l’enseignement grammatical: Étude sur l’“Ars Donati” et sa diffu-sion (IVe–IXe siècle) et édition critique (Paris: CNRS, 1981) — and studies of particular centers of teaching and learning. See especially John J. Contreni, The Cathedral School of Laon from 850 to 930: Its Manuscripts and Masters, Münchener Beiträge zur Mediävistik und Renaissance-Forschung 29 (Munich: Arbeo-Gesellschaft, 1978), and David Ganz, Corbie in the Carolingian Renaissance, Beihefte der Francia 20 (Sigmaringen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 1990).

- The categories of schoolbook (or classbook), miscellany, and glossed manuscript overlap but are not coterminous, and there are challenges of definition that attend each. A classic discussion of the distinction between glossed manuscript and schoolbook is Gernot R. Wieland, “The Glossed Manuscript: Classbook or Library Book?,” Anglo-Saxon England 14 (1985): 153–73. The manuscripts discussed below are all miscellanies, and they are all schoolbooks in that they contain curricular material, though their individual roles in educational contexts were probably varied.

- Anna Dorofeeva has outlined a useful theory of early medieval miscellanies, emphasizing the practical potential of these materials, which fill the role of “local encyclopedias” in many subject areas, as “a response to an increasing need for information.” See Anna Dorofeeva, “Miscellanies, Christian Reform and Early Medieval Encyclopaedism: A Reconsideration of the Pre-Bestiary Latin Physiologus Manuscripts,” Historical Research 90 (2017): 665–82, at 678.

- St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek 728, p. 8: “De doctrina Christiana libri IIII in volumine I.” Printed in Paul Lehmann, Mittelalterliche Bibliothekskataloge Deutschlands und der Schweiz, vol. 1: Die Bistümer Konstanz und Chur (Munich: Beck, 1918), 66–82.

- St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek 728, p. 20: “Item partes Donati minores atque maiores et Onorati de finalibus litteris et declinationes et commentarium Sergii in partes Donati et Ysidori liber et liber Capri de ortographia et Bedae de metrica arte. Haec omnia in volumine I.”

- James E.G. Zetzel, Critics, Compilers, and Commentators: An Introduction to Roman Philology, 200 BCE–800 CE (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 356.

- For a recent reconsideration of theories underpinning text editing and the “tension between classical methodology and medieval texts,” see Carmela Vircillo Franklin, “Theodor Mommsen, Louis Duchesne, and the Liber pontificalis: Classical Philology and Medieval Latin Texts,” in Marginality, Canonicity, Passion: Classical Presences, ed. Marco Formisano and Christina Shuttleworth Kraus (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 99–140, at 103.

- For example, studies of several of the manuscripts discussed below: Louis Holtz, “Le Paris lat. 7530, Synthèse cassinienne des arts libéraux,” Studi medievali 16, no. 3 (1975): 97–152, and Bernhard Bischoff, Sammelhandschrift Diez B. Sant. 66. Grammatici Latini et catalogus librorum. Vollständige Faksimile-Ausgabe im Originalformat der Handschrift aus der Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kultuerbesitz (Graz: Akademische Druk- und Verlangsanstalt, 1973).

- Barbara Bordalejo describes these approaches and problems in “The Genealogy of Texts: Manuscript Traditions and Textual Traditions,” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 31, no. 3 (2016): 563–77.

- The possibilities of network-driven approaches for the humanities in general and for medieval manuscripts in particular are currently being articulated: see the recently published volume by Ruth Ahnert, Sebastian E. Ahnert, Catherine Nicole Coleman, and Scott B. Weingart, The Network Turn: Changing Perspectives in the Humanities (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), as well as the discussion of analysis of medieval manuscripts and their relationships by Gustavo Fernandez Riva, “Network Analysis of Medieval Manuscript Transmission,” Journal of Historical Network Research 3, no. 1 (2019): 30–49.

- The list appears in Bischoff, “Libraries and Schools in the Carolingian Revival of Learning,” 112–13. For additional information about the manuscripts and their contents, I have consulted Paolo de Paolis, “Miscellanee grammaticali altomedievali,” in Grammatica e grammatici latini: Teoria ed esegesi, ed. Fabio Gasti (Pavia: Ibis, 2003), 29–74. Martin Irvine, The Making of Textual Culture: “Grammatica” and Literary Theory, 350–1100 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 395–404, provides a useful though somewhat less granular reckoning of grammatical manuscripts and their contents, and Zetzel, Critics, Compilers, and Commentators, offers a monumentally thorough and helpful overview of the efforts to disentangle textual traditions within this body of material.

- See, for instance, Michael M. Gorman and Elke Krotz, Grammatical Works Attributed to Peter of Pisa, Charlemagne’s Tutor (Hildesheim: Weidmann, 2014).

- On “Sergius” and Servius, see Zetzel, Critics, Compilers, and Commentators, 319–24.

- See ibid., 174–75 and 279–80.

- Ibid., 334–35, outlines the problem, noting that “This is, as outlined above, extremely confusing” (335).

- On these texts, see Luigi Munzi, “Multiplex Latinitas”: Testi grammaticali latini dell’Alto Medioevo (Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 2004), 8–15 and 67–72.

- Vivien Law identified the manuscripts Paris, Bibliothèque nationale lat. 13025; Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale IV. A. 34; St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek 876; Bern, Burgerbibliothek Cod. 207; and Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Diez B Sant. 66, as possible reflections of court interests. See Vivien Law, The Insular Latin Grammarians (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1982), 100–101.

- On the issue of originality as it relates specifically to the study of grammar in the Carolingian period, see Louis Holtz, “Les innovations théoriques de la grammaire carolingienne: Peu de chose. Pourquoi?,” in L’héritage des grammariens latins de l’Antiquité aux Lumières, ed. Irène Rosier (Paris: Société pour l’information grammaticale, 1988), 133–45. The essays in McKitterick, ed., Carolingian Culture, provide a multifaceted assessment of Carolingian reception and originality.

- On the formation of ideas about the liberal arts in Carolingian culture, see John Marenbon, “Carolingian Thought,” in Carolingian Culture, ed. McKitterick, 171–92.

Bibliography

- Ahnert, Ruth, Sebastian E. Ahnert, Catherine Nicole Coleman, and Scott B. Weingart. The Network Turn: Changing Perspectives in the Humanities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020. DOI: 10.1017/9781108866804.

- Amiens. Bibliothèques d’Amiens Métropole, MS 426. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8452180f.

- Berlin. Staatsbibliothek, Diez B Sant. 66.

- Bern. Burgerbibliothek, Cod. 207. https://www.e-codices.ch/en/list/one/bbb/0207.

- Bischoff, Bernhard. “Libraries and Schools in the Carolingian Revival of Learning.” In Manuscripts and Libraries in the Age of Charlemagne, translated by Michael M. Gorman, 93–114. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994

- ———. Sammelhandschrift Diez B. Sant. 66. Grammatici Latini et catalogus librorum. Vollständige Faksimile-Ausgabe im Originalformat der Handschrift aus der Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kultuerbesitz. Graz: Akademische Drukund Verlangsanstalt, 1973.

- Boniface. Praefatio ad Sigibertum. Edited by Vivien Law. “An Early Medieval Grammarian on Grammar: Wynfreth-Boniface and the Praefatio ad Sigibertum.” In Vivien Law, Grammar and Grammarians in the Early Middle Ages, 169–87. Lon-don: Longman, 1997.

- Bordalejo, Barbara. “The Genealogy of Texts: Manuscript Traditions and Textual Traditions.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 31, no. 3 (2016): 563–77. DOI: 10.1093/llc/fqv038.

- Contreni, John J. “Learning for God: Education in the Carolingian Age.” The Journal of Medieval Latin 24 (2014): 89–129. DOI: 10.1484/J.JML.5.103276.

- ———. The Cathedral School of Laon from 850 to 930: Its Manuscripts and Masters. Münchener Beiträge zur Mediävistik und Renaissance-Forschung 29. Munich: Arbeo-Gesellschaft, 1978.

- de Paolis, Paolo. “Miscellanee grammaticali altomedievali.” In Grammatica e grammatici latini: Teoria ed esegesi, edited by Fabio Gasti, 29–74. Pavia: Ibis, 2003.

- Dorofeeva, Anna. “Miscellanies, Christian Reform and Early Medieval Encyclopaedism: A Reconsideration of the Pre-Bestiary Latin Physiologus Manuscripts.” Historical Research 90 (2017): 665–82. DOI: 10.1111/1468-2281.12198.

- Franklin, Carmela Vircillo. “Theodor Mommsen, Louis Duchesne, and the Liber pontificalis: Classical Philology and Medieval Latin Texts.” In Marginality, Canonicity, Passion: Classical Presences, edited by Marco Formisano and Christina Shuttleworth Kraus, 99–140. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198818489.003.0005.

- Ganz, David. Corbie in the Carolingian Renaissance. Beihefte der Francia 20. Sigmaringen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 1990.

- Gorman, Michael M., and Elke Krotz. Grammatical Works Attributed to Peter of Pisa, Charlemagne’s Tutor. Hildesheim: Weidmann, 2014.

- Holtz, Louis. Donat et la tradition de l’enseignement grammatical: Étude sur l’“Ars Donati” et sa diffusion (IVe–IXe siècle) et édition critique. Paris: CNRS, 1981.

- ———. “Le Paris lat. 7530, Synthèse cassinienne des arts libéraux.” Studi medievali 16, no. 3 (1975): 97–152.

- ———. “Les innovations théoriques de la grammaire carolingienne: peu de chose. Pourquoi?” In L’héritage des grammariens latins de l’Antiquité aux Lumières, edited by Irène Rosier, 133–45. Paris: Société pour l’information grammaticale, 1988.

- Irvine, Martin. The Making of Textual Culture: “Grammatica” and Literary Theory, 350–1100. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Laistner, M.L.W. Thought and Letters in Western Europe, AD 500 to 900. London: Methuen, 1957.Law, Vivien. The Insular Latin Grammarians. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1982.

- ———. “The Study of Grammar.” In Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation, edited by Rosamond McKitterick, 88–110. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Lehmann, Paul. Mittelalterliche Bibliothekskataloge Deutschlands und der Schweiz, Vol. 1: Die Bistümer Konstanz und Chur. Munich: Beck, 1918

- Marenbon, John. “Carolingian Thought.” In Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation, edited by Rosamond McKitterick, 171–92. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- McKitterick, Rosamond, ed. Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- ———. The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987. London and New York: Longman, 1983.

- Monumenta Germaniae historica, Poetae Latini 1. Edited by Ernst Dümmler. Berlin: Weidmann, 1881.

- Munzi, Luigi. “Multiplex Latinitas”: Testi grammaticali latini dell’Alto Medioevo. Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 2004.

- Naples. Biblioteca Nazionale IV. A. 34.

- Paris. Bibliothèque nationale de France, lat. 13025. https://gal-lica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8423831v.

- Riva, Gustavo Fernandez. “Network Analysis of Medieval Manuscript Transmission.” Journal of Historical Network Research 3, no. 1 (2019): 30–49.

- St. Gallen. Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 728. https://www.e-codi-ces.ch/en/list/one/csg/0728.

- St. Gallen. Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 876. https://www.e-codi-ces.unifr.ch/fr/list/one/csg/0876.

- Wieland, Gernot R. “The Glossed Manuscript: Classbook or Library Book?” Anglo-Saxon England 14 (1985): 153–73. DOI: 10.1017/S0263675100001320.

- Zetzel, James E.G. Critics, Compilers, and Commentators: An Introduction to Roman Philology, 200 BCE–800 CE. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Chapter 2 (69-91) from Social and Intellectual Networking in the Early Middle Ages, edited by Michael J. Kelly and K. Patrick Fazioli (Punctum Books, 05.02.2023), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.