It is hardly a coincidence that it was only with the emergence of the first spatial foci of the Christian cult that the veneration of images can also be traced among the Christians.

By Dr. Michael Lipka

Professor of Religious Studies

University of Patras

Theoretically speaking, the number of visual forms of divine concepts is infinite. As with all concepts, though, Roman culture is highly selective in its choice of dominant visual forms connected with the divine. These were often labeled, and thus became, ‘types’ or, as I shall call them, ‘iconographic foci’. The totality of such forms shall be called ‘iconography’.

The iconography of pagan Roman gods may be conveniently divided into human-shaped and non-human-shaped representations. Human-shaped representations form the vast majority of official Roman cult images. Non-anthropomorphic cult objects are few. To begin with, we must mention the spear of Mars (apparently displayed in the Regia together with other fetishes such as two lances [hastae Martis] and two shields [ancilia]). Other cases are the boundary stone (terminus) of Terminus, the flint-stone (silex) of Iuppiter Feretrius, the baetyls of Magna Mater and Elagabal, and the flame of Vesta. Some further remarks are in place, however.

With regard to the spear of Mars, a number of sources attest explicitly to its divine nature.380 But apart from the fact that the worship of such an object would be unique among the official cults of Rome, the spear was displayed not in a temple, but a profane building, viz. the Regia. I have already argued above that it was predominantly the connection with divine space that turned a statue into a cult statue.381 If am right, it is legitimate to conclude by analogy that the spear was in fact not an equivalent to the cult statue of Mars, but originally a symbol of the martial powers of the king (and not the god) residing in or close to the Regia.

As for the remaining aniconic representations, their exceptional character can be briefly surveyed. Terminus was not only aniconic, but also immovable, i.e. exempted from exauguration, and worshipped under the open sky, i.e. explicitly not in a temple. In his divine form, he was thus truly indistinguishable from the thousands of actual boundary stones in and outside the city. It was this indistinctiveness which gave every boundary stone in the landscape a strongly divine aura as a potential ‘cult statue’ of the god. In other words, the aniconic appearance of Terminus served very practical ends. Iuppiter Feretrius appears to be the only hypostasis of an otherwise anthropomorphic Roman god that was simultaneously worshipped in non-human form (that is, of course, if we exclude the case of the spear of Mars). This can be explained if we assume that the epithet Feretrius did not originally denote a specific Iuppiter-type, but an independent deity that was worshipped in the particular form of a sacred stone ( just like Terminus), before merging with Iuppiter.382 Even gods that were originally worshipped in an aniconic form soon received a human iconography. Thus, Magna Mater was transferred from Asia Minor (where she was normally worshipped in human form) in the shape of a baetyl, but appears in Roman art as a female gure, recognisable by a turreted crown on her head and/or lions accompanying her. In the same vein, the meteorite of the god Elagabal soon assumed human iconography.383 Vesta is represented in anthropomorphic form during a lectisternium performed in 217 B.C.384 Statues of her are also attested earlier on the Forum, on the Palatine and elsewhere in Rome.385

In short, official iconographic foci in Rome were, or soon became, anthropomorphic. By contrast, private cult practice showed its usual flexibility in this respect. It is sufficient to refer to the worship of a coin by the gens Servilia, which allegedly presaged the vicissitudes of the family.386 The cult of Vesta in the Forum Romanum may have been a residue of such private worship, possibly from a royal context.

Another indication of the tendency towards personification is the fact that human-shaped cult images of abstracta are attested from very early on: for instance, the cult image of Fortuna in the Forum Boarium (sixth century B.C.?)387 and other extant Republican cult images of abstract notions from Rome (Fortuna Huiusce Diei, Fides, Mens [?]) are all anthropomorphic.388 The same tendency towards personification is further supported by divine nomenclature. In order to create divine ‘personal’ names from abstract nouns, the latter are often slightly modified in order to mark their ‘personal’, non-abstract aspect. For example, the river was Tiber, while the river-god appeared as Tiberinus; robigo denoted the mildew that befell the grain, while Robigus was the god who averts it; flos was the ‘flower’, Flora the patron goddess of vegetation; Portunus the god of harbours (portus), Ianus the protector of entrances (ianua) etc. One should also remember that many so-called ‘functional’ gods were similar to, but not identical with, the Latin word denoting their competences.389 On a psychological level, there can be little doubt that such a creation of ‘proper names’ from appellatives served to transform the appellative notion into a more familiar, ‘god-type’ person with an individual name.

Often, iconographic aspects of Roman gods were adopted from outside. Most obviously, the identification of Roman gods with their Greek counterparts was omnipresent in Roman iconography from early on. For instance, we find Volcan iconographically identified with Hephaistos in Rome from at least the beginning of the sixth century B.C.390 Being foreign did not imply a lack of focal potential in terms of iconography. Greek cult statues were transferred to Rome and served there as cult statues in the second century B.C.;391 indeed, Augustus chose works of famous Greek artists as cult statues for his new Palatine temple of Apollo.392 On the other hand, it would seem that a new iconographic type was created for the cult statue of Mars Ultor (see below). Accordingly, it was not the provenance of the iconographic type but the spatial setting in which it was displayed that mattered.393

Iconography was, on occasion, directly linked to its particular spatial setting. One may refer to the case of Terminus, who, apart from his non-anthropomorphic appearance, had special spatial demands, i.e. a hypaethral cult place. Another case in point might have been Vesta in her Forum temple, whose aniconic cult (if there has ever been such thing) related perhaps to the fact that she was worshipped in a circular sanctuary. Gods connected with lightning, such as Iuppiter Fulgur or Semo Sancus, may generally have been worshipped in an aniconic form, given their distinct functional foci. Therefore, it may be no coincidence that according to reliable sources their temples were hypaethral.394

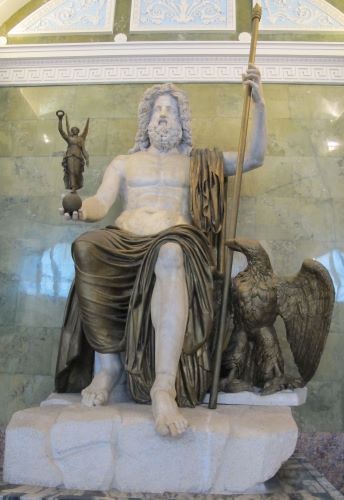

The vast majority of Roman gods, for example the ‘functional gods’ or many deified abstract notions, had no iconography at all. Normally, it was only the more popular deities who were fixed by iconographic focalization. This meant that the worship of major Roman gods focused where it did, on a limited number of types from a vast pool of potential visual representations of the god. Even among those types that were actually realized in Roman art, only a small number—i.e. the actual cult images—served as iconographic foci. For instance, Iuppiter could be represented in many different ways. However, his Capitoline cult image, the iconographic focus of the cult of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus, was fixed, viz. the god was represented seated and bare-breasted, with a cloak around his waist and legs.395 By contrast, the cult statue of Iuppiter Tonans represented the god naked, stepping forward and holding a sceptre in his right hand and a thunderbolt in his left.396 Similarly, the cult effigy of Mars Ultor is seen standing upright in martial pose, wearing a cuirass and helmet and leaning on a lance with his right hand. In his left hand he holds a shield.397

In other words, while countless different representations of divine concepts were conceivable, the number of actual iconographic foci was extremely limited. For a modern observer it is not always easy to distinguish both categories. A case in point is the findings from the Iseum Metellinum, where five or six marble heads from statues of Isis were unearthed in 1887. They clearly confirm that Isis was conceptualized within the same sanctuary in many different ways: all the heads belong to different types.398 But iconography was not necessarily tantamount to cultic focalization. It is quite possible that none of the heads actually represented the iconography of the cult statue of the Iseum Metellinum.

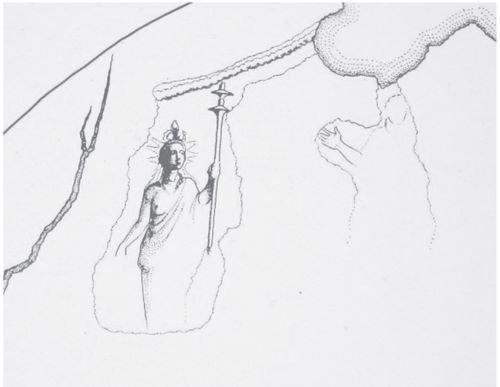

In fact, Isis is a good example of the arbitrary selection of actual iconographic foci. Despite the wealth of archaeological material, only three iconographic types of the Egyptian goddess have hitherto been identified with types of cult statues of the goddess. Isis Panthea is found on coins (see below), and it has been suggested that Isis Frugifera may be represented in a mutilated relief, found close to the theatre of Marcellus, in the second century A.D., though the work may be a Roman copy of a Hellenistic prototype.399 However, the identification of this Isis-type with Isis Frugifera is based solely on the millet stalks seen to the right of the goddess. Unfortunately, the relief is damaged on either side. One may wonder, then, whether Isis Frugifera would not better be identiFIed with the well-documented Isis-Demeter type, conventionally depicted standing upright, with a torch in her right hand, an ear of corn in her left and a modius on her head. This form of the goddess is also attested in Rome.400 By contrast, at least one iconographic type of Isis Pelagia or Pharia is well known. Here she is represented as striding to the left or right and holding, with her two hands and one foot, a sail that appears to be bellied out by the wind. Some of these representations belong to the first century A.D. or even earlier. However, the vast majority is found in the second century, with many on eastern coins. The first archaeologically attested Roman examples apparently belong to the second century A.D.401 Despite the good documentation of this type, it has been questioned whether this was the iconography of the actual cult statue of Isis Pelagia. Other Isis-types may have replaced it.402 The only certain fact is that there was a temple or shrine to Isis Pelagia in the city, for which we have epigraphical evidence.403

The emperor had no specific divine iconography of his own. Rather, his divine nature had to be conceptualized artificially through assimilation with traditional gods, most notably Iuppiter (but also through other deities according to imperial taste). This meant a double similarity: the iconography of the emperor had to reflect both the individual features of the monarch and those of a specific god to such an extent that each was separately recognizable. There were essentially two ways to achieve these ends, physical assimilation and divine attributes. Both were often combined.

To begin with physical assimilation, statuary types of Augustus and other rulers were frequently modelled on Iuppiter types, most notably the cult statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus. Indeed, the latter was the first Jovian type to be assimilated into the imperial image, and is already attested from the early imperial period onward.404 It is more than likely that the cult statue of Augustus, erected after his posthumous dei cation in his new temple, imitated this type. Indeed, the layout of his temple itself may well have imitated that of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus.405 Other cases of physical assimilation of Augustus to a god are generally ambiguous, unless supported by specific attributes. A relatively clear case is a cameo from Vienna, on which the victorious princeps is depicted upright in a quadriga drawn by four Tritons, clearly imitating a well-known posture of Neptune. A slightly earlier cameo from Boston shows the princeps, again in a quadriga, this time drawn over the waters by horses. Augustus is clearly identified with Neptune through the trident in his left hand.406 A number of coin issues, some of which (though hitherto ascribed to eastern mints) may be of west-ern or even Roman origin, depict Augustus in the shape of Iuppiter, Apollo, Neptune or Mars.407

Another way to assimilate the emperor to divine concepts was through the addition of divine attributes. Many imperial attributes were more or less reminiscent of specific traditional deities, especially Iuppiter. For instance, Augustus was represented on coins struck in Rome during his lifetime as carrying the Jovian sceptre.408 It is with this attribute of the highest god that the princeps appears on a cameo possibly of the Augustan age or slightly later,409 and on the Gemma Augustea.410 The Jovian eagle is depicted next to Augustus on the same gem, and also on a coin issue from the East dating from 27 B.C.411 Similarly, the thunderbolt appears next to the head of Augustus on a coin issued in Rome under Tiberius,412 while the same symbol is depicted on coins from the East even during Augustus’ lifetime.413 In sculpture, the princeps is represented in a famous bronze statue from Herculaneum with a thunderbolt. The piece is presumably of Augustan date and may have been manufactured in Rome.414 The princeps also appears with the aegis in the Cameo Strozzi from the Augustan period.415 Apart from such Jovian symbolism, we find the monarch with the characteristic staff of Mercury (caduceus), e.g. on a terracotta plaque from the Horti Sallustiani,416 on an engraved gem from the Marlborough collection,417 and on a wall decoration of a Roman villa.418 A denarius of 39 B.C. shows the head of Octavian on the obverse and a caduceus on the reverse side. However, the legend on the reverse reads Antonius Imperator.419 One may also refer to the trident, a requisite of Neptune, in the hand of the princeps on a cameo from Boston, referred to above.420 Capricorn, Augustus’ zodiac sign, is frequently depicted in connection with the head of Augustus on eastern coins.421 The laurel, originally an Apollonian requisite, was reinstrumentalized as a sign of Augustan triumph in the form of two laurel trees planted at the entrance of the monarch’s Palatine residence. It is documented elsewhere in Augustan art, for example on the Augustan compital altars.422

Apart from all this detailed evidence, it is important to keep in mind the general principle of similarity that binds it together: while the actual realization of the imperial iconography lay in the hands of artists and differed according to their means, talent and time invested, the actual principle under which these artists endeavored to establish the divinity of the emperor was not time-bound. By compiling corpora of ancient imagery such as LIMC and other reference works, modern scholars easily overlook the fact that not only the preservation in time, but also the actual realization of an iconographic type was a matter of chance. The emperor could be represented in the posture of Iuppiter, or with an eagle or a thunderbolt or the aegis, or a combination of these: the principle of similarity allowed for countless substitutions and omissions as long as recognizability was guaranteed. Even if all images of the divine emperor that had ever been manufactured in the ancient world were preserved, this collection would remain a rather arbitrary set. A Roman artist could have easily added to this corpus on the principle of visual similarity, even if he eventually decided not to.

Iconographic foci interacted, especially in the imperial period. For instance, Valetudo, goddess of personal health, borrowed her iconography and the snake as a requisite from her nearest Greek correspondent, Hygieia. She appeared thus on the reverse of a Roman coin struck by Mn. Acilius in 49 B.C. (the head of Salus is depicted on the obverse).423 Meanwhile, the old Roman goddess of ‘public welfare’, Salus (Publica), whose cult in Rome was certainly much older than the dedication of her temple in 302 B.C.,424 eventually adopted the snake from Hygieia/Valetudo in the second half of the rst century A.D. in her new shape as Salus Augusti: the reason being that in the meantime the emperor’s personal health had become tantamount to public welfare.425

The interaction of iconographic foci can best be demonstrated by the example of Isis. The gradual expansion of her functional foci led to an usurpation of various symbols and iconographic types of other traditional gods. In her most extreme form, she appeared as all-goddess (panthea), perhaps as early as the first half of the first century B.C., on a Roman coin type struck by the moneyer M. Plaetorius Cestianus (figs. 2 a, b). This early date for a pantheistic Isis type has been called into question, but it is beyond reasonable doubt that the coin represents a pantheistic deity, whether under the name of Isis or that of another deity.426 Alföldi, the first to recognize Isis Panthea on the Cestianus issue, gives further evidence of coins and gems for such pantheistic deities in the first century B.C.427 Later, Isis Panthea is also represented on bronze dedications via the various attributes of traditional gods (signa panthea), dating perhaps to the second century A.D. Similar bronzes have been found representing Venus.428

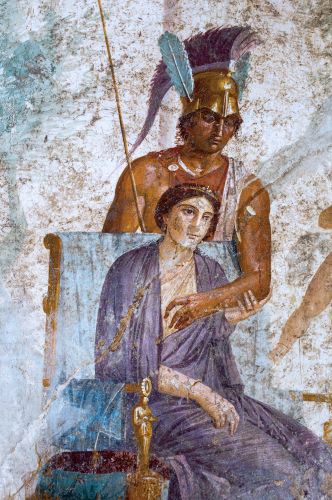

Apart from the pantheistic Isis, a number of types of the Egyptian goddess reflect iconographic foci of traditional Roman deities. Isis-Fortuna, he most popular syncretistic Isis type, may have had her origin in Hellenistic Delos.429 The best known example of this type is the Isis-Fortuna from Herculaneum, dating to the first century A.D., now in the Museum of Naples (fig. 3). Characteristic is the ‘Isis knot’ on the chest and the horns with the plumed disc on the head of the goddess. Meanwhile, requisites of Fortuna are the steering oar in the left and the cornucopia in the right hand.430

As far as Rome is concerned, there is a marble statuette from the Vatican Museums (fig. 4) and another, now in Florence, but perhaps originally from Rome. Both date to the second century A.D.431 A special case is a marble statue of Isis-Fortuna, found in an aedicula (shrine/lararium?) on the Esquiline and dating to the era of Constantine. The statue was apparently found in situ, together with other furnishings of the aedicula. Isis’ syncretistic iconography was ‘framed’ by marble sculptures of other gods (though decidedly smaller in size), which include both traditional Roman deities such as Iuppiter and Apollo, and Egyptian deities such as Sarapis and Harpocrates.432

Isis was assimilated not only to Fortuna, but also to Demeter.433 This syncretistic Isis-Demeter type is attested on a relief (fig. 5) found in the Via della Conciliazione in Rome in 1941 and now in the Capitoline Museums. The relief is attributed to the first half of the second century A.D.434 It shows four figures standing, (from left to right) the dedicant (head missing), Isis-Demeter, Sarapis and Persephone (?). Cer-berus is represented between Isis-Demeter and Sarapis, Harpocrates between Sarapis and Persephone, both approximately half the size of the other figures. Isis is characterized by the ‘Isis knot’, while she holds a torch in her right arm, wears a calathus and perhaps carries (the stone is broken) ears of corn in her left hand. The two former elements, at least, are clear requisites of Demeter. If the figure on the right is indeed to be identified with Persephone, she again has adopted foreign iconographic foci, namely the sceptre and the sistrum in her lowered left hand. It has been suggested that, despite the location of the find, the piece was manufactured in Alexandria.435

Another representation of Isis–Demeter is found in a wall-painting discovered in a house under the Baths of Caracalla in 1867 (now in the Antiquarium of the Palatine). Unfortunately, the painting is in a poor condition. It appears that Isis is depicted wearing the basileion and holding a torch in her right hand, and perhaps ears of corn in her left. The painting may be dated approximately to the second half of the second century A.D. (fig. 6).436

There is no need to further elaborate on iconographic foci of various forms of Isis. It is clear that even if no pieces of art had been lost over the centuries, completeness in conceptual terms would be beyond reach. For a conceptual catalogue of such pieces, in marked contrast to a historical positivistic catalogue, would also have to include those works that could have been manufactured, but never were. For a conceptual approach, then, the historical boundaries of execution and preservation are much more artificial.

Although Christian art is in evidence in Rome from the second century A.D.,437 the Christian god had no iconographic foci in the capital until the age of Constantine. In a magisterial study, the Christians’ rejection of idolatry throughout the Mediterranean was thrown into relief by N. H. Baynes more than fifty years ago.438 Numerous passages from Justin, Origen, Eusebius and other early Christian authors demonstrate beyond doubt that the early Christians steadfastly abided by the third commandment with uncompromising austerity: “You shall not make for yourself a graven image . . .”.439 Despite the occasional scorn poured by educated pagans on the adherence to idolatry,440 it was, in fact, their great opponent, i.e. the early Christians (following the Jewish precedent), who enforced, with a rare perfection, a complete ban on idolatry.

For our task, it is important to note that the absence of idolatry (and hence of iconography and iconographical focalization) was intrinsically connected to a lack of spatial focalization of the early cult of the Christian god. For spatial and iconographic focalization went hand in hand: an iconographic focus implied a spatial focus, i.e. the place where the icon was erected.441 It is hardly a coincidence that it was only with the emergence of the first spatial foci of the Christian cult that the veneration of images can also be traced among the Christians. The watershed was the era of Constantine. Our first reliable witness, Eusebius, mentions for instance icons of Peter, Paul, and Jesus.442

Of course, the lack of iconographic foci in the early Christian and Jewish traditions was not only the result of blind and unselfish obedience to the third commandment. Any iconographic focalization would have implied an exclusion of other iconographic concepts. However, such an exclusion could scarcely be reconciled with the postulated omnipotence and omnipresence of the Jewish and Christian concepts of the divine. If god had a shape, this shape had to be located somewhere. In other words, the presence of god, and as a result his powers, would have been limited. Besides, the avoidance of iconographic focalization made a reinterpretation and adaptation of the Jewish and Christian gods into an existing iconographic environment an easy task. For instance, in its iconographic indistinctiveness the Christian god could be easily interpreted as Iuppiter, Mars, Isis or other gods.This avoidance of focalization was one reason for the conviction, harbored by many pagan proselytes, that the Christian god was not just an addition to the existing pagan pantheon, but its abstract synthesis. Furthermore, in promotional terms, in their lack of iconographic fixation the Jewish and Christian gods were much more versatile and marketable than their divine competitors. In fact, in terms of iconography (as in other respects) these two forms constituted the only truly international divine concepts in the ancient world.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 1.5 (88-102) from Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach, by Michael Lipka (Brill, 04.30.2009), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license.