The emphasis on founding explanations for different disasters was always laid on two major issues.

By Dr. Jussi Hanska

Professor of History

Tampere University

Introduction

When the acute danger was over and people were coming out of their shelters to estimate their losses, they started to look for explanations for what had happened. Writers of annals and chronicles, theologians, and quite likely ordinary persons as well, started to wonder what had caused the disaster. Medieval society produced different models to explain natural disasters. Jean Delumeau analysed them in his study about the explanations for the Black Death. He distinguished three major explanatory categories typical to the different strata of society.

The first explanatory category was that of learned natural philosophers. According to them, the Plague was caused by celestial phenomena, such as comets and conjunctions of the planets, or putrefied vapours. The second one was that of ordinary people. They were inclined to find scapegoats and were convinced that someone caused the Plague on purpose. The guilty persons had to be discovered and duly punished. The third one was that of the preachers. They taught that God was angered by the sinfulness of mankind, and had decided to have revenge on them. Therefore it was advisable to try to placate Him by doing penance.255

Delumeau’s categories are useful not only for understanding the Black Death, but also for understanding the reactions of people to other natural disasters. However, this model should not be seen a monolith. It was not the case that only the learned accepted scientific explanations. This would have been rather peculiar considering they were mostly members of the clergy. The ordinary people likewise were not always searching for scapegoats. Sometimes they adopted the other explanations. In short, Delumeau’s explanatory categories were not limited to the socio-educational strata of society distinguished by him. Nevertheless, these categories may have originated from these different groups, and they certainly were predominant in them.

Furthermore, more often than not, these various explanatory categories are found together in different combinations. We cannot honestly say that there were significant groups who believed that natural disasters were caused by spiritual powers only. Neither can we identify significant groups who believed that natural disasters were caused by natural causes only. Most people were aware of all three major explanatory categories, but chose to emphasise one of them, while still acknowledging the feasibility of the other ones. As Piero Morburgo has detailed in his essay on the plague, in the end the emphasis on founding explanations for different disasters was always laid on two major issues, firstly the relationship between God and nature and secondly on the sinfulness on men and the necessity of his redemption.256

Scapegoats and Political Explanations

Since this book deals mainly with religious responses to natural disasters, Delumeaus’s first explanatory category, the scapegoats will be passed over with just few remarks. The search of the scapegoats lead inevitably to violent acts towards persons and social groups that in the eyes of later historians were nothing more than innocent scapegoats.

According to Emanuela Guidoboni the need to find scapegoats who could be blamed was typical in connection with natural disasters. She writes that the need to find scapegoats to explain disasters was by no means a Christian speciality, but a universally diffused way of responding to serious calamities. Finding a scapegoat would restore the cognitive order disturbed by thecatastrophe.257 Thus the possibility of pointing out a guilty party would return the community to its usual state. Guidoboni’s primary evidence dealt with a sixteenth-century earthquake in Ferrara, Italy, but his ideas are equally relevant for evidence concerning medieval natural disasters.

The potential scapegoats were normally found between two broad categories. They were either foreigners within Christendom, such as Jews, Muslims (in Spain and Sicily), and Heretics, or the black sheep of the Christian community such as notorious sinners and, especially during the Late Middle Ages, witches. Witchcraft and traditional folk healing methods were slowly demonised during the last two centuries of the Middle Ages even though the larger scale witch-hunts belonged to the early modern age.258

Before that time witchcraft and natural magic were seen as merely superstitious practices, sinful yes, but not dangerous or necessitating serious persecution. A good example of the earlier attitude is exhibited by the thirteenth century inquisitor Étienne de Bourbon, who did not bother to persecute old women healers and diviners (‘vetulae’), since he considered them to be merely simpletons who did not know what they were doing.259

People who did not belong to the community were considered unreliable. They were always potential scapegoats. Here it is not necessary to relate the details; enough has been written about the Jews causing the Black Death by poisoning the wells as well as about other potential scapegoats for famine and plague.260 What needs emphasis is that the search for scapegoats was not by any means limited to the Black Death. Similar tragedies took place in connection with other major disasters, some of them well before the Black Death; the Jews, to mention but one example, were accused of the great earthquake of 1348 and consequently a large number of them were burned alive.261

One must keep in mind that blaming some minority group was not always a sign of mass psychosis. Such accusations were also raised for political reasons, especially when other Christians were accused. One means of medieval propaganda was to claim that the sins committed by the political opponents were the cause of natural disasters. If propagated well enough, such accusations could, of course, give birth to sufficient indignation and anger or redirect the already existing emotions of disaster victims towards chosen scapegoats and thus cause violent reactions.

Let us look at few practical examples of blaming political or religious adversaries for the occurrence of natural disasters. The first example plays with the political and ideological differences between the Apostolic See and Frederic II. Salimbene de Adam wrote:

‘In that year [1284] God struck the Pisans with pestilence, and many people died, according to the words written in Amos VIII [8:3]: “Many shall die”—-The sword of God’s wrath killed Pisans because they had rebelled against the Church for a long time and captured in the sea the prelates on their way to Council, which was convocated by the late pope Gregory IX.’262

Salimbene referred to the event of 3 May 1241, when the Pisans captured the Genovese fleet carrying money and delegates to the General Council summoned by Gregory IX. The Pisans were supporting the cause of Frederic II and thought that by intercepting the delegates they could prevent the Council from taking place. Among those captured were two cardinals and several bishops. Due to the absence of the captives and the difficulties met by many other delegates on the road the Council never took place.263 These events occurred more than forty years before the above-mentioned pestilence broke out. God obviously was in no hurry to take vengeance.

In another passage Salimbene de Adam described the flood of 1284 in Venice, and makes a casual comment about its cause:

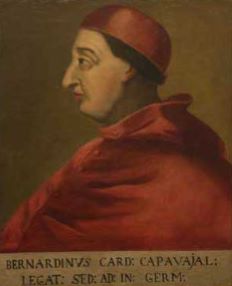

‘And the lord Bernardino, Cardinal of the Roman curia and legate, who then lived in Bologna said that this disaster happened to Venetians because they were excommunicated at the time.’264

The Cardinal in question is Bernardino, cardinal of Porto. He had been nominated to work as papal legate in central Italy, to drum up support for the Guelfs, and to arrange the preaching of crusade against the Aragonese. The Venetians were excommunicated because they supported the king of Aragon, Peter III against Charles of Anjou, the paragon of the papal see. The issue in question was who should rule the kingdom of Sicily.265

Not only were the enemies of the Church blamed for political reasons. Occasionally, the scapegoat was found inside the Church. A good example is to be found in Matthew Paris’ Chronica Majora. Matthew shows all through his chronicle his feelings about the papal taxation of the English church. There are literally dozens of passages where he complains about the avarice and exactions of the Roman curia. Therefore it does not come as a surprise that he should see the avarice of the Roman curia as a reason for Divine wrath. In 1250, the Northern Sea rose unexpectedly. The English coastal areas round Harlburn, Lincoln, and Winchester suffered badly. The inundation of the sea was also felt in the Dutch shores. After describing the damage Matthew says: ‘Is there any reason to wonder that such things happen, when the Roman curia which should be the fountain of all justice, is instead a source of unspoken enormities.’266

If one looks at the examples in which some other person or community is blamed for a disaster, one notices that in most cases such disasters are described from a considerable geographical or chronological distance. The chronicler is not personally involved in the disaster, but has heard about it through second-hand sources. The central motive for producing an account of the disaster is not the disaster itself, but rather the political message that can be connected to it, or, as in the case of Tyre’s earthquake reported by Étienne de Bourbon, a need to teach a moral lesson. This is not to say that the chroniclers were not concerned about the disaster, and about the loss of life. They indeed were and often produced a detailed description of the damage done. Nevertheless, these sources lack the feel of personal involvement.

Scientific Explanation

Natural philosophers and other learned persons sought to give rational explanations to natural disasters. According to them such phenomena could be explained, at least partially, according to the laws of nature created by God in the beginning. Hence not all the disasters were the result of God’s direct intervention. Some natural events were used to forecast disasters, such as comets and constellations of the planets whereas others were used to explain their causes.

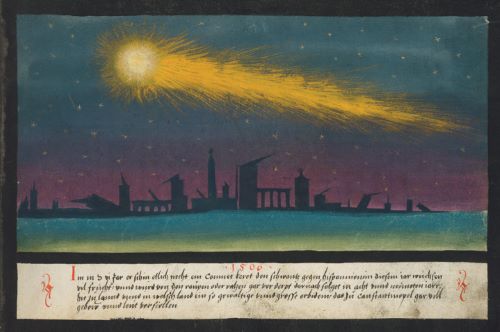

Almost all the appearances of comets were thought to predict some major catastrophe, either a natural disaster or a man-made disaster such as war. Dominican Aegidius de Lessines crystallised the function of comets as messengers of bad news in his De essentia, motu et significatione cometarum from the latter half of the thirteenth century. He wrote that comets are a sign rather than a cause of disasters. Since they are made of the element of fire, they predict mainly evil things such as floods, earthquakes, and the destruction of cities.267

Academic astrologists in Paris took the view that the Black Death was caused by the unhappy constellation of Jupiter, Saturn and Mars that had taken place in 1345. On the other hand, there were also sceptics who were not willing to believe in the influence of comets. Matteo Villani commented on several explanations of the plague proposed by astrologists by writing that there had been numerous similar constellations of the planets and yet nothing had happened before.268 Nevertheless, it is obvious that astrological explanations did enjoy considerable popularity among the learned circles.

So prevalent were the religious explanations, that whenever scientific explanations as causes for natural disasters were put forward, they were almost without exception accompanied by religious ones. Giovanni Villani’s description of the 1333 flood in Florence reminds us of this fact. Villani writes:

‘On 1st November 1333 the rain began. It poured for four days and four nights, with fearful lightning and thunder; and the river rose, and rose, until the water broke down walls, then buildings, and ended by carrying away the three main bridges, all this with inestimable ruin and loss of life…. It was agreed that this flood was the worst catastrophe in the history of Florence. And it its aftermath a question arose, and was put to the learned friars and theologians, and to the natural philosophers and astrologers: namely, whether the flood had occurred through the course of nature or by the judgement of God.’269

It is understandable that the Florentines were upset about the flood. Villani compares the flood of 1333 to the earlier flood of 1269. According to the old people who were trustworthy witnesses and who had personally seen the earlier the flood of 1269 the present one was without any doubt worse. The floods of 1333 were not only a problem for Florence, but there are numerous sources from other cities of Central Italy, such as Parma, Bologna and Ferrara, that testify to the enormous effects of the disaster.270

Villani not only posed the problem of different explanations, but he also answered it. The very chapter in his chronicle that is entitled D’una grande questione in Firenze, se’l detto diluvio venne per giudicio di Dio o per corso naturale starts with expounding thoroughly what the astrologists had said about the unfavourable astrological signs, that is, bad constellations of the planets and the eclipse of the sun. These were interpreted as causes of the flood. The lengthy description with its complex details reveals that Villani was himself interested in astrology.271

Then he moved on to the explanation presented by the theologians of the city. They, as Villani writes, responded saintly and reasonably that the astrologists might very well be right up to a certain point, but not altogether. If God had not wanted the flood to happen, it would not have taken place, regardless of the conjunctions of the planets or other signs of zodiac. God, being the Creator, has ultimate power over nature. He had created the world out of nothing, and He is therefore completely capable to remake, change, shape, or undo it as He sees fit.272

In this the Florentine theologians followed the reasoning of Thomas Aquinas. Thomas had concluded that the established natural laws under normal circumstances operated perfectly well, God nevertheless was capable and omnipotent to change them and work miracles.273 This idea of Thomas was by no means original; he merely presented it in impeccable scientific language.

Villani’s listing of the reasons for natural disaster is in many ways representative.

We find similar combinations of natural and supernatural explanations in many earlier sources. A good example is Matthew Paris’ description of two earthquakes: one in England (in 1247), and another in Savoy (in 1248). About the first one he writes:

‘In this same year, on the ides of February, that is on the eve of St. Valentine’s day [13 February], an earthquake was felt in various places in England, especially at London and above all on the banks of the River Thames. It shook many buildings and was extremely damaging and terrible. It was thought to be significant because earthquakes are unusual and unnatural in these western countries since the solid mass of England lacks those underground caverns and deep cavities in which, according to philosophers, they are usually generated, nor could any reason for it be discovered….’274

In this passage Matthew notes that according to scientific opinion earthquakes are not common in England. He is relying on the authority of Aristotle and the commentaries on his Meteorologics. Thomas Aquinas’ commentary makes clear that earthquakes were believed to occur because of vaporisation of water in deep underground caverns. If there are holes in the ground the steam can come out harmlessly and cause winds, but if such holes are absent, pressures build up and finally cause earthquakes. The most seriously affected areas according to Aristotle and Aquinas were coastal regions, in particular those places where the sea was believed to go under the land, as was the case in Sicily.275 Isidore of Seville already put this Aristotelian explanation of earthquakes forward in his De natura rerum. It received much wider audience through Vincent de Beauvais’ enormously popular Speculum naturale and numerous other popular writings in the late medieval period.276 This Aristotelian explanation with comments from Aquinas continued to bean accepted scientific model well into the early modern age. Marcello Bonito used it to explain earthquakes as late as in 1688.277

Matthew Paris implies that even when such underground caverns were lacking people were keen to find some natural explanation for the earthquake. Only when natural explanations could not be found did the people finally turn to supernatural explanations. Matthew describes the case of Savoy in a following manner:

‘At this time, in the region of Savoy, namely in the valley of Maurianne, certain towns, five in fact, were overwhelmed and swallowed up, with their cowsheds, sheepcotes and mills, by the neighbouring mountains and crags, which, as a result of a horrible earthquake in some caverns inside them, were torn away and pulled out from their normal place. Many say that three religious houses were struck down there but one chapel escaped. Itis not known if the destruction of the mountains which raged so horribly in that place occurred miraculously or naturally, but because about nine thousand persons and an incalculable number of animals were destroyed, it seems to have happened miraculously rather than through natural causes.’278

Here we have the perfect example of harmony between scientific explanations and those relying on divine intervention. In the first place Matthew describes what happened, and tells that it was caused by the movement of some underground caverns. Having stated this completely valid and at that time accepted geological cause of earthquake, he nevertheless concludes that it was caused by miraculous means. He sees no problem whatsoever in connecting the scientific explanation with that of Divine wrath.

Matthew Paris’ story is a classical example of the inadequacies of medieval scientific explanations. The first thing he had misunderstood was the nature of the catastrophe itself. It was not an earthquake, but the collapse of a part of mount Granier that buried several villages in Savoy.279

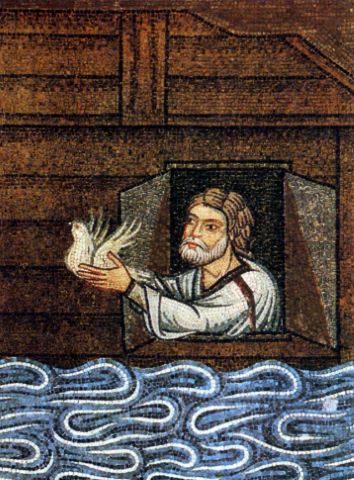

A similar combination of natural science and religion is found in Thomas de Cantimpre’s Liber de natura rerum. Thomas gives natural explanations for floods, which according to him were especially frequent in the East. During warm weather water could vaporize into steam and rise up into the clouds. The heat of the sun evaporated even the small amount of water that did get through. This caused huge underground water concentrations. When these water storages became too large, the water simply found its way out with pressure and this caused floods. After this explanation Thomas described Noah’s flood, which was caused by God as a revenge for the corruption of mankind. The natural processes described earlier could not explain the latter flood, according to Thomas. The reason of Noah’s flood was the huge mass of water, which God had in creation placed above the firmament that was brought down to earth when the floodgates of heaven were opened.280

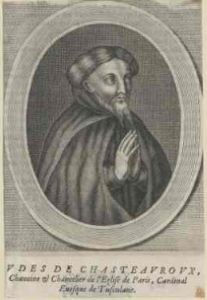

Turning towards the homiletic evidence we find more examples of the intermingling natural and theological explanations. Cardinal Eudes de Châteauroux preached in Viterbo sometime after the earthquake of 1269. He commented that philosophers and scholars were in a habit of discussing the reasons of earthquakes, thunder and lightning and how they can before told. He then put forward the Aristotelian standard explanation for earthquakes and lightning. He even took the trouble of explaining this rather complicated theory in a more easily understandable way. He said that the heat closed within under ground caverns that finally erupts violently causing earthquakes can be understood by thinking about chestnuts. When they are roasted the vapour of the heat builds up inside them until the pressure breaks their shells.

Despite all this commitment to scientific arguments, Eudes soon nullified them by writing that it is useless to search for natural explanations of earthquakes and lightning or the signs preceding them. We should all know that the real cause (causa efficiens, causa finalis) for such disasters are God’s wrath, and the signs preceding them are the sins of men.281

Another good example is Vincent Ferrer’s second Rogation Day sermon. At first, Vincent gives a scientific explanation why Rogation time is the natural period for seeking divine aid against natural disasters. He reveals that during that period the earth starts to get warmer, and finally becomes hot. This implies that large amounts of vapour rise to the upper spheres of atmosphere. There the air is colder which causes the vapours to condensate producing thunder and lightning, which finally reach the earth with disastrous consequences, such as the destruction of crops, vineyards, fruits and other temporal goods. This apparently natural process is turned into a theological explanation by adding that God has the supreme control over nature. Therefore, to guarantee that nature was kept under control and showed benevolent face to mankind, the holy fathers had decreed that Rogation time, more than any other moment of the year, was the period when men ought to pray to God to intercede.282

Vincent, being a Dominican preacher, not surprisingly seemed to adopt the view of Thomas Aquinas mentioned earlier. God does not normally make things happen in nature. He has laid down the laws and basic principles according to which nature works. Nevertheless, being omnipotent, He is capable of intervention whenever and if He so chooses.

Jean-Claude Schmitt has reached the same conclusion by studying diseases and healing in the Middle Ages. He writes that religious readings of disease did not exclude the idea of natural causes, yet these were always subordinate to the Divine plan. Hence there was no place for scientific causalities in the modern sense, that is, causalities that could be verified and falsifiedexperimentally.283 There was no need for them as God was omnipotent, and His actions were not limited by natural laws and causalities laid down by Him.

One might add that this predilecture of a mixture of supernatural and scientific explanations was not typical for the Middle Ages only. It remained fashionable well into the modern period. Paul Slack writes about the causes of the plague in the early modern period: ‘The explanatory system within which the plague was set had been handed down from the past. In essentials it had been established at the time of the Black Death.’ In fact, as we shall see later on, it had been around centuries before the Black Death. Slack observes that while God was seen to be the first cause of the plague, He normally worked through secondary causes. Thus Supernatural and natural explanations for epidemics were interlocking parts of a single interpretative chain.284

Late medieval plague epidemics forced different writers of pastoral literature to pay more focused attention to the problem of tribulations. In 1493 the Observant Franciscan Bernardino Tomitano da Feltre was preaching on the Plague in Padua. In his rather long sermon, Bernardino mentions all the standard scientific explanations, starting with astrology and finishing with the obligatory quotations from Aristotle. Even though Bernardino accepts without arguing the importance of the planets and everything said in the Meteorologics, he nevertheless leaves the final word to God, stating that nothing agonising in this world happens against the will of God.285

Perhaps even more interesting is the plague sermon by his namesake and fellow Franciscan Bernardino da Busti. He thoroughly analysed different opinions on the reasons and predictability of epidemics in his sermon on the pestilentie signis, causis et remediis. Bernardino was writing in the latter half of the fifteenth, or in the beginning of the sixteenth century when society was under the continuous threat of plague epidemics.286 Bernardino’s plague sermon turned out to be extremely pragmatic. One might even call it a ‘how to survive a plague’ manual. It is very likely that Bernardino was not thinking exclusively about the salvation of souls, but also wanted to give his readers some practical advice. This combination of practical advice and religious instruction was fairly common in the early modern period.

Bernardino starts arguing whether it is possible to know in advance when God will punish mankind. He quotes Saint Paul (Romans 12:33): ‘O the depth of the riches of the wisdom and of the knowledge of God! How incomprehensible are his judgements, and unsearchable his ways.’ Some people, says Bernardino, use this biblical quotation to prove that it is impossible for mortals to know when and how God is going to punish them. According to Bernardino, this is true as far as one is discussing the exact moment and the means of punishment. There are some signs, however, that allow us to deduce that Divine punishment is imminent, as it is said in Luke21:25: ‘There shall be signs in the sun and in the moon and in the stars.’

Some people argue against this with the words of Jeremiah (10:2): ‘Be not afraid of the signs of heaven which the heathens fear.’ Nicolaus de Lyra responds to this by saying that it is superstitious and heretical to argue that constellations of stars and signs of heaven could affect the rational mind and turn it to sin, as is also attested by the third book of Thomas’ Summa contra gentiles. Nevertheless, Bernardino adds, the constellations of the stars and movement of the heavenly objects do affect physical phenomena such as droughts, rains, winds, sterility, sickness and epidemics.

Having established the theoretical basis of his opinions, Bernardino proceeded to the actual message of his sermon, that is, signs, reasons for, and remedies for epidemics, and wrote:

‘And when such epidemics are to come, no one can know for sure, sincethat information is only in possession of God, and He can send them withina moment without any preceding signs. However, when they come becauseof natural causes, most often through heavenly and atmospheric bodies, itis possible to know from certain signs when it is going to happen.’287

Thus we see that Bernardino would seem to argue that natural disasters can happen through completely natural causes, in which case they can, at least with some kind of accuracy, be foretold by means of astrology and natural philosophical observation. They can, however, also happen through the will of God, and in that case there is no way of foretelling when they are going to happen. For God, being omnipotent can make them happen without the customary warning signs. Bernardino’s interpretation is much more moralistic than the scientifically oriented opinions of Thomas Aquinas and Vincent de Beauvais. Yet the essential message is the same: There are natural laws that apply for the disasters, but God, when He so wishes, is above them.

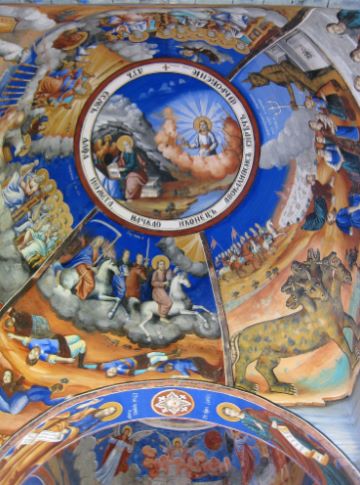

Apocalyptic Explanations

‘Then he said to them: “Nation shall rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom. And there shall be great earthquakes in diverse places and pestilences and famines and terrors from heaven; and there shall be great signs.”’

St Luke 21:10–11

During the Middle Ages the idea of the end of world and the coming of Antichrist was always present. The world was growing old, and the eventual end could lurk just around the corner. In this generally apocalyptical atmosphere there were times when apocalyptic expectations were even more fashionable and concrete than usual. The most important of these were the change of the millennium, the first half of the thirteenth century, and the immediate aftermath of the Black Death.

If we look at the peak times of apocalyptic thinking we see several explanatory factors. The change of the millennium hardly needs further elucidation. Full thousand years simply seemed to be convenient time span for the coming of the Antichrist or the second coming of Christ. The middle of the thirteenth century, especially the year 1260, was interpreted as a potential moment of apocalyptic cataclysm, thanks to the popular prophesies of the Calabrian abbot Joachim of Fiore. The first half of the thirteenth century was the hay day of Joachimism. Clerics as well as laymen, were preparing for the last days and the coming of the Anti-Christ when 1260, the crucial year in the prophecies of Joachim was approaching. These apocalyptic expectations were only reinforced by the early thirteenth-century pseudo-Joachite writings and the catastrophic situation in Italy just before the decisive year 1260. In 1258 there had been a serious famine, and the following year saw the outbreak of epidemics in many parts of the country.288

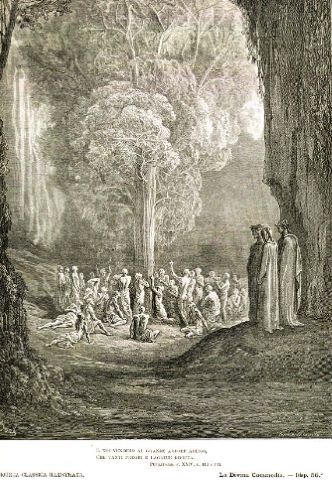

The flagellant movements of 1260 prove that this expectation of the last days was not monopolised by clerics who had first hand knowledge of Joachim’s writings. The fear for the approaching Antichrist and the end of the world was substantial enough to drive large numbers of people to the streets. They wore penitential clothes, they sang penitential songs, and flogged themselves. Norman Cohn points out that the famine of 1258, the following outburst of epidemic diseases, as well as the ravages of incessant warfare were seen through Joachim’s and pseudo-Joachite prophesies. He implies that this combination of virulent Joachimism and hard times was the driving force behind the flagellant movement of 1260.289

Although the eminent historian Raoul Manselli questions this representation, Marjorie Reeves and Gary Dickson seem to provide sufficient corroborative evidence to uphold Cohn’s vision. It might not have been a question of pure Joachism in the theological sense. Yet the role of prophetic and apocalyptic expectations in the flagellant movement seems undeniable. The flagellants fed on a widespread apocalyptic mood, which derived from many sources, but certainly was tainted with Joachimist prophecies.290

Joachim of Fiore’s grim prophecies were supported by the onslaught of the Mongols against the Christendom. It had started in 1241–1242, when Mongol forces devastated large parts of Eastern Europe causing serious loss of population. All too conveniently from the point of view of Joachim’s prophesies they were by the time of 1260 expected to renew their attack, and had indeed done so in Poland. The hordes of attacking nomads were sometimes interpreted to be the armies of Gog and Magog mentioned in the Apocalypse.291

In light of all this, it is no surprise that all natural and man-made disasters occurring within a close range of the key year 1260 were seen as sure signs of the end. One might add that apocalyptic expectations were by no means limited to Italy. The English Benedictine monk Matthew Paris reflected on the general apocalyptic mood by ending his account of the year 1248 with the following statement: ‘The end of the world is apparent from many indicating arguments. These are: “Nation shall rise against nation, and there shall be earthquakes in diverse places and such things.”’ Matthew paraphrased Luke 21:10–11. Hence he quite likely had in mind ‘pestilences, famines and terrors from heaven.’292

Similar evidence can be gathered from other sources from the first half of the thirteenth century. Jacques Berlioz gives a few examples of eschatological motivated stories in exemplum collections. He indicates, however, that non-eschatological explanations for natural disasters were far more common in preaching materials, and ventures that apocalyptic themes were rather hazardous in connection with sermons.293 The preachers did not want to give rise to any apocalyptic movement because experience had thought that such movements were not easy to control. Once out of ecclesiastical control, apocalyptic movements tended to cause all sorts of public disturbance, such as pogroms against the Jews and violent riots.

The passing of the crucial decade of the 1260’s relaxed the general atmosphere in Europe. Nevertheless, apocalyptic theories remained popular through the late medieval period, also during better times. Cardinal Eudesde Châteauroux preached in Viterbo after the earthquake of 1269. He took his theme from Isaiah 24:18–19: ‘The floodgates from on high are opened, and the foundations of the earth shall be shaken. With breaking shall the earth be broken, with crushing shall the earth be crushed, with trembling shall the earth be moved. With shaking shall the earth be shaken as a drunken man.’ It is difficult to imagine a more suitable Bible quotation when preaching about an earthquake. Having stated his thema, Eudes continues: ‘God made this threat through Isaiah the prophet. It will be completed and have its consummation in the end of the world when the day of the final judgement approaches.’294 Here we see Eudes painting the damage and destruction caused to Viterbo with apocalyptic words from Isaiah. He reminds his audience that such scenes are preparing us for the last times.

The waning of Joachim’s popularity caused a decline in eschatological expectations. They became fashionable again in the latter half of the fourteenth century. There were several reasons for pessimistic outbursts and apocalyptic fear in those decades. The economic situation in Europe had declined after the reasonably prosperous thirteenth century. A worsening climate caused crop failures and lower yield ratios. There had been serious food shortages from the beginning of the century and the catastrophe became complete with the coming of the Black Death and the subsequent outbursts of plague. There was also a religious crisis. The papacy had moved to Avignon, and when it returned to its natural post in Rome the exile was followed by a schism. One cannot forget the importance of the hundred years war that caused additional damage to France. In addition, the fifteenth century saw the military advance of the Turks who, according to the pattern established during the Mongol attack of the 1240’s, were seen as precursors of the last times.295

With these darkening perspectives in mind, it might be useful to take a look at a contemporary chronicle and its views of the last times. The Franciscan Johannes Winterthur describes two important events around the middle of the fourteenth century, namely the earthquake of 1348 and the Black Death. The most interesting aspect in this passage of his chronicle, however, is not the description of the actual events, but the explanation given to them:

‘The aforementioned events, that is, the earthquake and the pestilence are evil precursors of the maelstroms and storms of the last days according to the words of the Saviour in the Gospel: “And there shall be great earthquakes in diverse places and pestilences and famines etc.”’296

Johannes is referring to the Luke 21:13, a Gospel passage that discusses the signs of the end of the world. It is quite obvious that he was convinced that the great pestilence and other natural disasters of the time signified of the approaching end. Nor was he alone with his ideas. These mid-fourteenth-century earthquakes in Carinthia and Italy were generally interpreted to be ‘messianic woes’ which were to usher in the Last Days.297 It should be remembered, however, that by the latter half of the fourteenth century, referring to the world’s end in connection with natural disasters had become a well-established topos amongst medieval chroniclers. Nevertheless, given the other evidence, such as popular contemporary militant millenarian movements, we may safely assume that a considerable number of people genuinely believed that the end was at hand. The same attitude can be observed even in the sixteenth-century sources. Miguel-Angel Ladero Quesada who has studied Andalusian earthquakes between 1487 and 1534 writes that fear of the Apocalypse was always a factor in explainingearthquakes.298

In an intriguing argument, Robert E. Lerner holds that the crucial function of eschatological prophesies and interpretations of the Black Death was a comforting one. According to him, eschatological writings, and rumours were ‘intended to give comfort by providing certainties in the face of uncertainty and must have helped frightened Europeans get about their work.’299

World history was predestined and planned by God. Disasters such as the Black Death were merely before-written chapters in a great story moving towards its logical conclusion. Seeing things in the context of a Divine plan offered some comfort to people who had either lost their families or friends during the plague, or were simply devastated by the measure of destruction caused by it. According to Lerner’s interpretation, eschatological writings created order out of chaos and gave a definitive and understandable meaning to the plague. The human catastrophe that was otherwise way beyond reason became understandable and maybe even acceptable as a part of a Divine plan.

Divine Intervention

God’s Punishment

Despite the popularity of apocalyptic explanations for natural disasters, not all ecclesiastical writers were keen to speculate about the last days. Many preferred to see the workings of Divine providence on a more restricted local level. They took the view that natural disasters were indeed products of Divine intervention but did not interpret them necessarily as signs of the approaching end of the world. God was merely punishing sinners for their misdeeds and this punishment was measured out locally.

All the historians of the Black Death and following plague epidemics acknowledge that such disasters were explained as Divine punishments for the sins of man. Some medieval preachers and theologians were keen to blame mankind as a whole; others were satisfied with geographically more limited groups of sinners, that is, people living in the affected community. Explaining natural disasters as a sign of Divine wrath was by no means a medieval invention. Its history goes back to the earliest history of mankind. Jean-Noël Biraben refers to several examples in Greek mythology and in the Old Testament.300

Scholars of comparative religion and anthropology have long since established the idea that explaining natural, or for that matter other, disasters with Divine intervention was and is typical for all “primitive” societies. In fact, one line of anthropology has been to classify societies according to their level of rationality. All societies were envisaged to develop from magic through religion to the ultimate goal that is scientific rationality. According to this theory some primitive societies of today are now on a level of development the western society used to be once.301

It is important to notice that the explanation of divine wrath as a cause of natural disasters is not fundamentally different from the eschatological explanation. Indeed these two seem to be related. One is a micro-level explanation suitable for explaining local disaster and its impacts upon the community, whereas the other is macro-level explanation, which can be used to explain all natural disasters in generic way; they are simply heralds of the approaching end of the world.

Even the redeeming activities and remedies suggested by these explanations were the same. People were exhorted to do penance while there still was time. The micro-level explanations stressed that penitential activities could be a means to save the community from the actual disaster. For the macro-level explanation, the actual disaster was not of a particular importance. It was merely one in the chain of many similar events, some of which already had happened, whereas some still had to come. What was important was the historical culmination point predicted by these disasters. It was for the final reckoning that mankind was urged to do penance, not to obtain salvation from the present menace.

These micro- and macro-level explanations were not mutually exclusive. While natural disasters were interpreted as heralds of the approaching end, their immediate effects might still be lessened with the proper penitential attitude and concrete acts of satisfaction. It is this way of thinking that allows us to understand why the flagellants of 1260 were crying out loud for peace and mercy.302 It was quite reasonable for them to believe that God would show some mercy for the chosen ones when the last days would come. After all, Jesus himself had promised in Matthew 24:22 that ‘for the sake of the elect those days will be shortened.’

Among the numerous preachers that gave both macro- and micro-level explanations of divine intervention we can single out Eudes de Châteauroux. Earlier we quoted the apocalyptic passage of his Sermo exhortatorius propter timorem terremotum. Having presented an apocalyptic, macro-level explanation for earthquakes, Eudes continues with micro-level explanation on the level of individual cases:

‘Nevertheless, it has been fulfilled many times in particular cases and we are afraid that we being sinners, it is again fulfilled in our times, for the prophet explains the cause of this threat in the words immediately the preceding aforementioned words [that is, in the words of Isaiah preceding the thema of the sermon]: “My secret to myself, my secret to myself. Woe is me! The prevaricators have prevaricated: and with the prevarication of transgressors they have prevaricated. Fear and the pit and the snare are upon thee, O thou inhabitant of the earth. And it shall come to pass, that he that shall flee from the noise of the fear shall fall into the pit: and he that rid himself out of the pit shall be taken in the snare: for the flood gates from on high etc.”

For our transgressions have been multiplied, and therefore the wrath of God has flown over men bringing along famine, pestilence, sword, lightning and storms, earthquakes and other kinds of scourges from God so that even brute animals such as lions, wolfs and even insensitive elements are seen to in surge against the mindless. They will in surge as vengeance against offences of the wretched men who will not cease provocating God. Let it be that this is secret for the people who do not understand that such things come because the wrath of God, the Lord informs this to his friends and He did told it to prophets. Therefore Isaiah says: “My secret to myself, my secret to myself”, for it was revealed to him, if to no one else, that God sends aforementioned punishments to sinners also in the present world, and much greater ones in the future, and therefore he said twice my secret to myself.’303

Here we see that Eudes first evokes the images of the final judgement and then continues with showing that God punishes the sinners also in this world. As such punishments, Eudes mentions in particular the most common natural disasters and wars. He does not claim that natural disasters happen exclusively because of sins, but when reading between the lines we get the impression that this it is exactly what he means.

Later in the same sermon Eudes hints at the sins he thought were the specific reasons of God’s wrath. It is quite likely that this discussion was meant to be understood in a generic fashion. It was not addressed to the inhabitants of Viterbo and other towns that suffered from the earthquake. This is obvious because Eudes chose sins that were treated in all treatises of moral theology. He takes from Isaiah the words fear, pit, and snare. He links them with the three sins of 1st John 2:16, that is, concupiscence of flesh, concupiscence of eyes and the pride of life. These three forms of concupiscence according to strong medieval tradition were connected with the three capital sins of lechery, avarice, and pride. Within the framework of Seven Capital sins these three were considered to be the most important or dangerous ones, the other four, namely wrath, envy, sloth, and gluttony were given far less attention.304

When medieval man tried to understand natural disasters, the Bible was the first place to turn to. Archetypical stories, such as Noah’s flood and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah were referred to time and time again. For example, when Gregory of Tours and Paulus Diaconus described contemporary floods in their chronicles, they turned to the example of Noah’s flood, and later writers followed their example. It was only natural that these stories were used to give meaning to contemporary natural disasters for, as Saint Augustine had written: ‘In the Old Testament the New lies hid; in the New Testament the meaning of the Old becomes clear.’305 In the medieval exegetical and ecclesiological tradition the New Testament era not only covered the events described in it, but incorporated the history of the Church until the Final Judgement. The writings of the Old Testament were a storage from which man was encouraged to seek parallels and typological explanations for contemporary events and problems.

Sometimes the examples or archetypical stories of the Old Testament are openly mentioned, at other moments their influence can be read between the lines. An example of the latter is the description of Giovanni Villani concerning the above-mentioned flood of 1333 in Florence. He wrote that it rained continuously four days and four nights. The water rose to unforeseen levels so that it seemed that the floodgates of heaven had been opened (‘…che pareano aperte le cataratte del cielo…’).306 When he wrote this passage, Villani obviously had in mind the passage of Genesis that describes the beginning of the flood, that is, Genesis 7:11. In the Vulgate text it reads: ‘…rupti sunt omnes fontes abyssi magnae et cataractae caeli apertae sunt.’ The source and inspiration of his language most likely was immediately recognised by his readers, who therefore were able to read a part of his message that may be lost to modern readers who are less familiar with biblical language. Using Noah’s flood as a point of comparison when describing floods was by Villani’s time a well-established literary convention. Numerous influential earlier historians, such as Gregory of Tours and Paulus Diaconus, had used it.307

The general tone or the moral lesson of these two Old Testament stories, that is Noah’s flood and Sodom and Gomorrah, directed the opinions of theologians. Natural disasters were perceived as a sign of God’s wrath towards sinners. Any other explanation would have been extremely difficult to argument with recourse to the Bible.

Consequently there is no lack of sources describing natural disasters as the revenge of God for the sins of mankind as whole, or more specific groups. Some of these sources have been indicated in different books concerning the history of death.308 Numerous others are found in manuscript and early printed sources. The French Dominican Étienne de Bourbon presented in his book Tractatus de diversis materiis predicabilibus a short description of an earthquake that took place in Tyre. The passage that interests us is found in a section of Étienne’s book dealing with the seven capital sins. Having named the subspecies of the sin of lechery (simple fornication, sacrilege, adultery, incest, and sins against the nature), Étienne underlines the dangers of sin against the nature (peccatum contra naturam) by telling a story of an earthquake in the form of an exemplum. According to a person whom Étienne knew well and who was present in Tyre during the earthquake, many people were crushed to death because they had been practising this abominable vice when the houses collapsed. Étienne compared the faith of the Tyre victims to those of sodomites of Genesis 19.309

The earthquake described in Étienne’s exemplum was not dreamt up to convince his readers. It actually had happened and is also mentioned by other sources, such as Jacques de Vitry’s Historia Orientalis. It was customary that a certain measure of truthfulness was required from exemplum stories. This has been shown with regard to the exemplum collection of Étienne de Bourbon. Several of his exempla have been studied critically and found to be based on real historical events.310 Étienne de Bourbon was not the only one to attribute the earthquake to the sinfulness of man. Francesco Pipinoda Bologna described it in his Chronicon and explained it with the exigentibus peccatis hominum topos.311

There is another interesting story among the exempla of Étienne de Bourbon, namely, the history of the collapse of Mount Granier in Savoy in 1248. We have already seen that the English Benedictine chronicler Matthew of Paris moved between natural and supernatural explanations when describing this catastrophe. His contemporary Étienne de Bourbon had no problems deciding that the earthquake was caused by Divine wrath. His exemplum makes the priest Jacques Benevais, a member of the count of Savoy’s retinue, responsible for the Divinely induced earthquake. Jacques had managed to lay his hands on the profits and lands of a priory just below Mount Granier by promising in exchange that he would persuade his master to join the papal party. Jacques and his accomplices had driven away the prior and the convent and were celebrating their success in the empty priory when God’s vengeance (literally) fell upon them in the night.312

Medieval sermon literature provides numerous additional examples. Federico Pisano Visconti stated in his first Rogation Day sermon that God sends three types of tribulations to mankind as punishment of their sins, namely, pestilence, famine, and the sword.313 The Dominican friar Aldobrandino da Toscanella wrote laconically that sin is the principal reason for our loss of spiritual and temporal goods.314 His confrere Jacques de Lau-sanne preached about drought. He implied that where physical rain is absent, spiritual rain, that is, rain of grace, would be missing as well. Jacques compared the state of sin to disease. When man is suffering from fever and internal dryness, his mouth is also unusually dry. Similarly, the sickness of sin causes drought.315

One of the most enlighting sermons is Jacques de Lausanne’s De pluvia vel pro alio tribulatione. The title suggests that we are dealing with a model sermon. Nevertheless, the text implies, as is also obvious from the context that it was originally delivered in connection with a flood. Jacques compared God to an archer who has drawn his bow and is waiting to let the arrow go to punish the sinners. The only way to avoid the archer’s punishment is to be on the side of the string, not on the side of the arch, that is behind rather than in front of the bow.

God’s punishment, which in this sermon is compared to an arrow, comes sooner or later, when the archer has grown tired of keeping his bow ready, that is, when the time of mercy and doing penitence has gone. If no sooner, it inevitably comes with the final judgement. However, God punishes also on a smaller scale before Judgement day. It is such smaller-scale punishment that the sermon is all about:

‘Therefore God, willing to punish the vices of these days seems to be willing to bring on a new deluge. We all are gathered here that we might find a remedy against this deluge, and we do not see other chance but appeal to God the archer so that he turns away from us the arch of his vengeance and turns to us the string of his mercy. This is the advice of Malachias: “And now beseech ye the face of God, that He may have mercy on you (for by your hand hath this been done).”’316

It is obvious that the original delivery of the sermon was connected with a religious meeting organised because of a flood, such as a mass in some station church before or after the procession. It is interesting to note that the preacher did alter the text of Malachias to make it a better fit for the occasion. Where the original text simply says that by your hand hath this been done, the version given by our preacher replaces the word this (‘hoc’) with the words this bad weather (‘hic malum tempus’). Such alteration of the biblical text was a common device to emphasise the homiletic message. A little trick like this sufficed to make the audience see more clearly the connection between their sinful activities and the bad weather and flooding.

An anonymous sermon pro pluvia on the theme Dimitte peccata eorum et da pluviam super terram takes King Salomon and uses him as an exemplary figure to drive home the lesson of sin as a cause of disaster. The preacher starts by introducing King Salomon. He tells that the king said numerous prayers to God, but amongst them were three very special ones. One was to obtain victory in battle, another against pestilence, and the third one to procure rains:

‘A third one for the rains. If heaven shall be shut up, and no rain will fall because of the sins of the people and the drought will lead to famine and lack of food in the land, this happens so that people may recognise their sins, invoke the generous Lord so that He may forgive sins of the people, and He may find it proper to concede rain to land. For this third prayer Salomon said the above-mentioned words, which we have very conveniently quoted here, for we see that because of our sins the sky is closed so that it will not rain on us. We see also such severe drought around us that famine is already setting on the land as well as shortage of food, and if He who only can help us will not come to our rescue, we fear more and more after each day. Therefore we must follow the example of that king who was so devote and so humble, and pray with these words: “Forgive their sins and give rain upon land.”’317

This sermon leaves very little room for speculation concerning the cause of the drought: people’s sinfulness, nothing more, nothing less.

The Dominican friar Jacques de Lausanne wrote about a drought in his sermon Ad impetrandam pluviam. He also made a comparison between bodily illness and sin. Just as the tongue of sick people is often dry because of the inordinate bodily temperature and internal dryness, drought of temporal waters in a similar fashion comes from the dryness and sins of soul. He quotes Psalm 142 to verify this message: ‘My soul is as earth without water unto thee.’318 Psalm 142 Exaudi Domine was one of the seven penitential Psalms that were sung during the catastrophe processions. Thus the context made the connection between sin and drought even stronger in the minds of the listeners than the outspoken words of the preacher. The comparison between bodily sickness and sins as a sickness of the soul was a medieval commonplace.

The sources are in most cases written by members of the clergy. Sometimes, however, they allow us to know to what extent the explanation of natural disasters with recourse to divine wrath was accepted by the population at large. For example, sometimes we get to know that the people took the liberty of deciding who were to blame without consulting the church. The Cistercian Abbot Johannes von Viktring, who described the epidemic of 1267 in Austria, wrote in his Liber certarum historiarum:

‘In the year of our Lord 1267 there came pestilence and hunger, destruction of cities and villages all over Austria. They were so bad that a large share of the population and almost all the cattle died miserably. Ordinary people claimed commonly that this epidemic was brought about by God because of the illicit matrimony of the king.’319

The population, or at least a considerable part of it, felt that the epidemic and famine were brought about by the sin of the king. Whether this attitude had developed spontaneously among the population or whether it was a product of ecclesiastical propaganda, we do not know. However, it seems obvious that the explanation of the clergy was appreciated and shared to some extent by the lay population.

Here we may remember the Florentine flood of 1333. Giovanni Villani repeats in his Cronica the considered opinion of the local theologians. They explained that God uses nature as a means to punish the sins of mankind, and He has the power to send his punishment according to the laws of nature, in supernatural means, and even against the laws of nature. However, the really interesting part is Villani’s personal opinion. He took the view that the flood was indeed caused by the outrageous sins of the Florentines, and that the whole city would probably have perished, had there not been the prayers of holy men and the religious communities, as well as the liberal alms given by the Florentines. These were good enough to invite God’s mercy and stop the flood.320

Villani did not limit himself to commenting on the particular flood in Florence. On a more general level he wrote:

‘But to return to our original question and its solution, and keeping in mind the above stated examples, which are true and clear, we may say that all the pestilences, battles, sackings and floods, arsons and persecutions, shipwrecks and exiles come upon us with the permission of Divine justice, to wash away our sins. Sometimes they come according to natural order, sometimes supernaturally, as Divine power sees fit.’321

A few important elements in Villani’s account deserve specific emphasis. At first it is interesting that he took such a great interest in theological reasoning. After all, Villani was not member of the clergy, but a normal Florentine merchant. His description of the theologians’ arguments is very detailed, and he does not limit himself to retelling their general arguments, but also repeats faithfully all the biblical quotations and other finesses used to argue the case. If Villani’s chronicle can be used as indicative for lay opinion on general, it would seem that at least in Florence, many people were deeply interested in the possible causes of the disaster. They were not willing to fatalistically accept what had happened, but were actively seeking to know the causes of their misfortune.

The story of Villani shows that at least some laymen took pains to listen, learn, and understood theological reasoning. What is even more important, they accepted the clerical theory of Divine punishment of sins as a cause of the catastrophe. Villani tells us that majority of the population turned to penance and took communion to placate God’s wrath.322 In Florence at least, astrologists, natural philosophers, and their followers were in the minority. The majority of the people believed that the disaster was brought upon them by their sins.

Divine punishment for the sins was the first explanation proposed in connection with the series of earthquakes that ravished the kingdom of Aragon in 1374. Penitential processions in three consecutive days were organised in the city of Barcelona soon after the worst of these earthquakes had struck in the night between 2 and 3 Mars. The most important relics from the churches were carried along the streets and the turnout of the crowd was exceptionally numerous. Not only were the citizens and clergy present, but also the royal family and nobility. It is obvious from the sources that both ecclesiastical and lay authorities believed that the earthquake was caused by the sins of people. Equal measures were taken in other Aragonian towns, such as Tortosa and Cervera. In Cervera, the particular sins were mentioned. A common opinion was that earthquake was caused by the evil habit of making oaths in the name of God, Holy Virgin or the saints or because of other blasphemies. Such practices were forbidden on the penalty of fine often gold pieces.323

The fifteenth-century preachers shared the opinions of their thirteenth-century predecessors. The German preacher Johannes von Werden continued to attribute natural disasters to divine punishment. He wrote that according to the Holy Scripture and Petrus Lombardus all the misery originates from sin, that is, it is a punishment for sin. Johannes specifies that misery in this context mean storms, disagreements, sterility of the soil etc. Naturally, the problems connected to agriculture, such as lack of fertility, are emphasised, since we are dealing with a Rogation Day sermon.324

The Italian Franciscan friar Bernardino da Busti, as we have seen above, took the view that natural disasters can sometimes be caused by totally natural reasons without any Divine intervention. Nevertheless, he stressed repeatedly that they also occur because of the sinfulness of the victims. Bernardino shouted theatrically to sinners: ‘O you wretched! Why do not you fear to offend God?’ Then he moved on to explain that the plague and the corruption of the air (and indeed any other adversities in this world) are in most cases sent by God without any preceding warning signs when He is angered by our vices. Bernardino offered two examples. The first one was from the early Christian writers and the latter, concerning a plague in Milan, came possibly from his personal experience. Bernardino told that in 1451, an extremely lethal pestilence struck the city of Milan and during it ‘innumerable men died every day’. The air was so polluted that if one took a piece of warm bread from the oven in the morning and put it out, it was totally spoiled by the evening.325

Having established that disasters fell upon mankind because God was angered by its sins, Bernardino moved on to discuss in more detail the sins that in his time were sufficiently upsetting God to make Him punish mankind with the plague. He started by saying that God indeed punishes men because of numerous sins, but that he will, for the sake of brevity, discuss only a few of these sins. As often happens when a speaker or preacher lets his audience know he is not going to speak for long, Bernardino launches into a description of sins that lasts for several pages. These included: sacrilege and vain glory among the clergy, idolatry, contempt of preaching, not paying tithes, gluttony, complaining about God, spreading rumours about others, unjust wars, deceitful business, fraudulent contracts, and ingratitude. The worst four sins, which Bernardino described with more detail, were abomination of Divine mandates, pride, robbery, and dishonest self-indulgence. In connection of the last one Bernardino emphasised sodomy more than anything else.326 Starting from Bernardino da Siena, sodomy had been one of the favourite subjects of fifteenth-century Italian preachers.

Demons on the Loose

There exists a slightly different version of this explanation of Divine punishment. In the above-mentioned examples, God was punishing the sinners directly by letting or causing nature to punish them. Some writers chose to believe that God was not personally punishing sinners with the help of nature, but He merely withdrew his protection and allowed the demons occupying nature to have their own way. This demonological explanation is encountered mostly in sources written by or ultimately addressed to ordinary lay people.

Vincent de Beauvais wrote in his enormously popular encyclopaedia Speculum naturale that the demons were expelled from heaven after the mutiny of Lucifer against God. They settled in the air to wait for the final judgement. From there they tempt people and cause storms. Vincent added that according to pagan philosophers and learned doctors the air is as full of demons as there are tiny dust particles in the sun’s rays.327

Preachers and moralists were quick to adopt this demonological explanation in their writings. Vincent Ferrer told his audience why they should organise processions and prayers in Rogation time. One of the reasons he mentioned was that when God had created heaven and earth, Lucifer and some other fallen angels started a rebellion against Him and were expelled from Heaven. Some of them went to hell where they torture sinners, others went to earth where they tempt us, and yet others stayed in the middle layers of the atmosphere. There they plot against people to destroy their crops, and thus to drive them to despair so that they will sin against God with impatience and blasphemies. According to Vincent, demons would have the power to destroy the whole world if God did not limit their activities.328 Therefore itwas essential to organise Rogation Day processions and litanies. If prayers would cease and God would withhold His protection, the demons would befree to have their way with mankind.

In essence this explanation of natural disasters is very similar to the above-mentioned explanation of God’s wrath. Even if it is the demons that do the damage and cause the disasters, they are only operating because God allows them to (‘Deo permittente’). Why does God permit them to destroy crops and do other damage to Christians? There are two obvious explanations, to tempt people and to punish the sinners.

We meet another example of this explanation in the pages of Villani’s chronicle. In the middle of explaining completely rational theological reasons for the flood, he retold an exemplum story he had heard from the abbot of Vallambrosa monastery, who was, as Villani notes a religious and trustworthy man (‘uomo religioso e degno di fede’). While praying, a certain hermit had heard the infernal rumble as if there were numerous men riding in a state of fury. He made the sign of the cross, opened his shutter, and saw a multitude of terrible black horsemen galloping by. One of them said to the hermit: ‘We are going to Florence to drown its inhabitants because of their sins, if God permits it.’329

The black horsemen were demons. It was a common topos of exemplum literature to present them in a form of black horsemen.330 The whole story isa very conventional exemplum story. It is so conventional that it makes one wonder whether the abbot of Vallambrosa had been affected by exemplum literature when telling the story to Villani. But leaving aside the form of the story, it is important to note that here again the supreme power of God is emphasised. The demons are able to drown the people of Florence only if God permits them to do it (‘se Iddio il concederà’). Thus the common point with Villani’s (or Vallambrosa abbot’s) story and Vincent Ferrer’s more theologically oriented explanation is that while the demons indeed are the executors of the actual destruction, they are only able to work within the limits laid down by God.

Even though the devil and demons were considered to have the power to bring on natural disasters, if not freely then at least with the permission of God, they were perceived as explanations very rarely when compared to the cases of direct divine intervention. Most commonly they are encountered in connection with one specific type of natural disasters, that is, storms and heavy winds as seen above. These were traditionally perceived as the work of demons.

Causality of Punishment

So far we have discussed the explanations of natural disasters, and found out that they were either explained by divine wrath or scientifically, but even the latter explanation could include an element of divine intervention. Now it is time to see how this model of natural disasters explained how God’s anger was operationalised and turned into something that nearly matches a mathematical equation, or a sentence of systematic logic. We start with the Sermo propter timorem terre motus by cardinal Eudes de Châteauroux.331 The very first chapter of the sermon makes this point in a manner, which leaves no doubt whatsoever:

‘”The earth shook and trembled: the foundations of the mountains were troubled and were moved.” [Ps. 17:8]. Job says in the fifth chapter [Job5:6]: “Nothing upon earth is done without a cause: and sorrow doth not spring out of the ground.” And in Thimeo: “Nothing is done without a legitimate cause preceding it.” Truly in earth there is no pestilence, no famine, no earthquake that happens without a cause, but nearly all the bad that happens is brought upon us by our sins.’332

At the end of his sermon Eudes also gave some advice to his readers concerning the remedies for natural disasters:

‘If we get angry with ourselves the wrath of God will cease, and then He will establish the pillars of earth, that is, make the earth stabile and suitable for the habitations of men, and remove the earthquakes and other things that are against us. Let us then pray that we shall do penance for our sins so that we may make the face of God happy and serene again, and desist from our sins, for when the cause ends, so ends the effect. In this help us Lord Jesus Christ who shall live for evermore. Amen.’333

The attention of the reader is drawn immediately to the piece of impeccable logic: ‘When the cause ends, so ends the effect.’ (lat. cessante causa cessabitet effectus). This quotation suggests a straightforward causality relation between sinfulness and natural disasters according to the following scheme:

sin = causa

natural disaster = effectus

Whenever there is causa, then there is also effectus. When the causa has been removed, the effectus will equally be removed. This inputs reason into the system. Instead of dealing with unpredicted and random occurrences, natural disasters turn out to be a part of the logical world order, which can be, if not controlled, then at least explained in a satisfactory manner. Order is made out of chaos.

It could be objected that too much is being made of a rather limited corpus of sources in claiming that natural disasters were always and almost mechanically explained with sin. This might be the case if we would have to rely on the substance of the sermons only; however, the similarities are not limited to what is said, they can also be found in the manner of presentation. Let us turn back to the catch phrase ‘When the cause ends, so ends the effect.’ It is significant that the same sentence or something closely resembling it can also be found in many other catastrophe sermons – so frequently that it cannot be a mere co-incidence.

Eudes de Châteauroux himself repeats it in another catastrophe sermon – Sermo in processione facta propter inundationem aquarum.334 The sermon begins with an exposition of the Genesis story on the creation of the world. ‘In the beginning God created heaven, and earth. And earth was void and empty, and darkness was upon the face of the deep.’ Eudes asks rhetorically why God allowed waters to rule the earth in the beginning and answers ‘because the world was void, that is, not bearing fruit and empty of inhabitants, and therefore there was no damage doing so nor anything to wonder about that he left earth be occupied by waters.’ Then Eudes comes to the bottom line of his argument:

‘In a similar manner there is nothing to wonder about the floods that come now, rather it is a miracle that God does not cover the earth with a new deluge because it is void and empty, truly void because it does not produce fruit, for in present times the earth does produce no or very little fruit. In these days the prophesy of third chapter of Habacuc seems to be fulfilled: ‘For the fig-tree shall not blossom: and there shall be no spring in the vines. The labour of the olive-tree shall fail: and the fields shall yield no food. The flock be cut off from the fold; and there shall be no herd in the stalls.’

Then follows a substantially large part of the sermon where Eudes explains his quotation from Habacuc. The fig tree signifies priests and the religious, the vines stand for prelates and princes, the olive-tree means burghers, and the fields are peasants. The sins of these social groups are the reason why the earth does not bear fruit and deserves to be punished with floods. Not surprisingly, Eudes draws on the deluge in the time of Noah as a parallel case from the Old Testament to show his audience what could happen, if man keeps sinning in a similar manner. For Eudes it is only reasonable that nature, which is a servant of God, should punish those who sin against God, just like the servants of a temporal lord punish those who insult their master. Every element of nature does this punishing according to its means: earth through earthquakes, water through floods, air through storms, and fire through lightning. This idea implies that Eudes too held the position that catastrophes happened according to the normal laws of nature, but yet in accordance with the will of God.

Having stated the true cause of the flood Eudes moved on to the encouraging part of his sermon. He wrote that God has mercy on the great multitude of sinners if he can find a few righteous amongst their number ‘and if our sins that are the springs of the abyss would come to an end, then the punishments inflicted on us by God would also come to end, that is, the floodgates of the heaven would be closed.’ This sentence is formulated exactly according to the model of cessante causa cesset et effectus. Only the word causa is changed to words peccata nostra and the word effectus with word pene.

It has been possible to find several other, even more obvious examples of the cessante causa cessat et effectus – topos in sermon literature. They prove that it was widely used and remained fashionable over an extended period of time. The following examples come from three different centuries. The first case is a late thirteenth-century sermon by Nicolas de Gorran titled Ad impetrandum serenitatem. This sermon starts as follows:

‘”And He brought the wind upon the earth, and the waters were abated” Gen. X [Genesis 8,1]. It has been known for ages that the waters started flooding because of the flood of sins. Similarly it happens that the rain comes pouring down because of the flood of sins. When the cause is removed the effect goes away easily too. Therefore those who make penance will receive divine favour so that their temporal adversities cease, as can be understood from what is said above, and where the receiving of divine favour is handled in words: “And He brought the wind.”’335

An anonymous Swedish late fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century preacher used this phrase as a thema of his sermon! It says in the margin of the manuscript Item sermo, the actual text starts with the words: ‘Who doubts that when the cause is removed the effect will pass away, that is, people would stop sinning, God would also cease punishing the kingdom [the kingdom of Sweden that is].’336

Bernardino da Busti used this same topos in his sermon de pestilentie signis, causis et remediis, written in the last quarter of the fifteenth century. He wrote that since it now is well established that the cause of pestilence is sin, it is possible to remove the pestilence by removing the sin. He quotes Aristotle to make this point and continues to argue it: ‘Elsewhere it is said that when the reason is removed, so is the effect….thus as sin, as stated above, is the cause of pestilence, therefore if the sin is removed so will be also the pestilence…Oh you sinners, if you do not want that God sends you pestilence, or if you do want him to stop one that He has already sent to you, stop sinning and the pestilence will also stop.’337

It seems beyond any doubt that the cessante causa cessat et effectus was a common feature of catastrophe sermons. The interesting question is: where did the notion come from? Considering the fact that the relation between sin and natural disasters was established as a completely predictable law, it should come as no surprise that it should have been described in juridical jargon. There is a close parallel in Gratian’s Decretals, although the context is completely different. I quote it in the original Latin, to highlight the linguistic similarities: ‘Sed sciendum est, quod ecclesiasticae prohibitiones proprias habent causas, quibus cessantibus cessant et ipsae.’338

Ever after Gratian, the cessante causa topos was used fairly commonly in different contexts, most extensively by Innocent III in his letters and privileges. It also comes up in constitutions of the Fourth Lateran Council. In the 36th constitution it says: ‘Cum cessante causa cesset et effectus, statuimus ut siue iudex ordinarius siue delegatus […].’ More important is, however, constitution 22. It states that corporal sickness is sometimes caused by sin, and urges medical doctors to advice their patients to call doctors of the soul, so that once the spiritual disease is eliminated normal medical healing can be started. This advice is followed by the remark ‘cum causa cessante cessat effectus.’339 Antonio García y García argues that this passage is modelled after Innocent III’s Commentarium in septem Psalmos poenitentiales.340 Thus the constitution 22 not only established for the times to come the connection between sin and physical disease, but it also presented a new useful topos for the catastrophe sermons.

It is very plausible that the authority of General Council constitutions was significant in popularising the cessante causa cessat et effectus topos. Nevertheless one has to take into consideration that it was already reasonably well known before the Fourth Lateran Council. To the present author’s knowledge, the first writer to use this topos to describe the relation betweens in and punishment was Petrus Comestor in his Historia Scholastica: ‘Etsanavit paralyticum ante se demissum per tegulas, primo remittens peccata ejus, quae fuerant causa morbi, quia quod ob causam fit, cessante causa cessare debet effectus.’341 Given the popularity of the Historia Scholastica in preaching circles, it is quite possible that this passage was in fact the primordial source for the cessante causa topos. Be that as it may, together with the 22th Constitution of the Fourth Lateran Council it was destined to sink into the minds of many clerical readers in centuries to come.

Purgatory in this World

It would be nice and convenient to have a single clerically promoted explanation for natural disasters. Alas, such is not the case. Not all the members of the clergy were promoting the theory of Divine wrath as a cause for natural disasters. Some of them were proposing a completely different explanation. God was not punishing or chastising sinners with natural cataclysms; He was merely testing the virtuous and the chosen ones sending them temptations and tribulations before granting them the ultimate reward in the kingdom to come. There were yet others who posited both of these explanations or put forward a synthesis.

This problem can be put into a wider context by asking: Why does the omnipotent God allow the existence of evil. Why does He allow evil people to prosper and, on the other hand, allow good and virtuous people to face adversities and sorrow? Or indeed, is there not a conflict between the evil in the world and the goodness of an omnipotent and omnipresent God? That is the so-called problem of theodicy, which ultimately was presented and answered by philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) in his Essais de Théodicée in 1710.342