The king had strong views on alcohol and women and he liked a well-ordered sung mass.

By Dr. Iona McCleery

Associate Professor in Medieval History

University of Leeds

Introduction

In 14381 King Duarte of Portugal died suddenly leaving a six-year old son as heir. The ensuing regency eventually led to civil war, a scenario that to some extent resembles the start of the Wars of the Roses in England. Although it has long been known that the illness or sudden death of the monarch could throw the country into disorder, political historians still pay limited attention to royal illness and medical historians have been slow to take on board the political implications of medieval belief in the “body politic” metaphor.2 Several historians have analysed the impact of Charles VI of France’s and Henry VI of England’s madness, Henry IV of England’s long illness and Baldwin IV of Jerusalem’s leprosy.3 Yet in all these cases, the point of view of the sick king is difficult to access. The writings of King Duarte so far seem to be unique in that they provide a personal view of royal well-being. When Duarte wrote in his advice book, the Loyal Counsellor, that “the health of the people is the health of the prince and the prince must greatly love his health,” his words should be taken seriously as far more than a metaphor.4 As a king who had suffered from melancholy in his youth, Duarte understood only too well what it would mean to the kingdom should illness return to disorder his body and soul.

King Duarte of Portugal produced two compilations informing us of his outlook on life, health and politics. The high-status manuscript containing the Loyal Counsellor was discovered in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, in 1804. Consisting of 104 chapters written in Portuguese, the existence of the Loyal Counsellor was noted by chronicler Rui de Pina in around 1500, but the only surviving manuscript seems to have left Portugal in around 1440.5 The king’s other work is a much less polished miscellany known today as the Book of Advice. Written almost entirely in Portuguese, the collection includes lengthy passages also found in the Loyal Counsellor, as well as twenty-five recipes and regimina. The oldest manuscript dates from c. 1600.6

In an earlier study of the Loyal Counsellor by the present author, it was argued that the text should be understood as a patient-authored narrative, unique for a layman of that time period and status.7 That study focused on the king’s melancholy and the crucial role it played in structuring the narrative. This new study explores the content of the Loyal Counsellor in much more detail, and more fully incorporates the Book of Advice into the analysis. The title reference to wine, women and song is partly meant to be humorous; as will be seen, Duarte had strong views on alcohol and women and he liked a well-ordered sung mass. In all seriousness, however, Duarte’s writings show that he advocated a prudent lifestyle very far from the “wine, women and song” image that is perhaps the one that most comes to mind today when modern people think of medieval royal behaviour.

The chapter begins by providing some context first of all for Duarte’s ill health and his writings. It then goes on to argue that Duarte lived by a concept called contentamento, which is perhaps as close as we can get to a medieval sense of well-being; finally, there is an analysis of Duarte’s complex relationship with food, drink and women, showing the close connections between his physical and spiritual well-being.

King Duarte of Portugal, His Illness and His Political Context

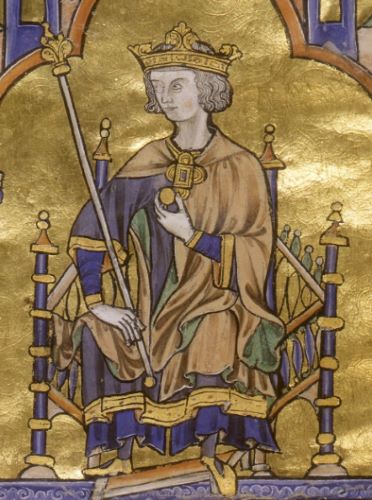

The short reign of King Duarte (1433–1438) is largely unknown to non-Portuguese historians. Duarte is overshadowed by his famous younger brother Henrique “the Navigator” who between 1415 and 1460 traditionally pioneered Portugal’s expansion into the Atlantic and down the African coast. More recent research suggests that other members of this well-connected and highly-educated family were also important: Duarte himself, his brother Pedro and his sister Isabel, Duchess of Burgundy.8 Duarte had in fact ruled Portugal for many years prior to his accession to the throne on behalf of his father João I who was preoccupied with North Africa.

Duarte was an effective legislator and administrator who counselled his brother Henrique against a disastrous campaign at Tangiers in 1437 in which their youngest brother Fernando was captured. Duarte’s death the following year, however, allowed Henrique to continue his ambitions for a personal African empire and encouraged later chroniclers like Rui de Pina, who wrote for Henrique’s spiritual heir his great-nephew King Manuel, to dismiss Duarte’s reign as an unimportant sideshow to God’s grand plan for Portugal. Pina said that Duarte died of plague, fever or sadness as a result of the Tangiers fiasco, thus indelibly linking his melancholy to political failure.9 Unfortunately, the nineteenth-century scholars who first studied the Loyal Counsellor accepted Pina’s assessment. The king still struggles to escape from the popular view of a feeble-minded man who “confessed to the dumb pages of his book.”10

Had Duarte not died prematurely at the age of forty-six his legacy could have been very different. The irony is that he may already have worried about what would happen if he died young, leaving a minor on the throne. Duarte was after all the son of a usurper, João I, who had exploited the chaos that ensued when his predecessor Fernando died prematurely in 1383 leaving an eleven-year old heiress.11 It is apparent from a reading of the Loyal Counsellor and the Book of Advice that there were two major health problems that Duarte wished to avoid: melancholy and plague, conditions that were closely connected to each other in his mind. Duarte tells us that he first succumbed to “the illness of the melancholic humour” in 1413 at the age of twenty-two when his father handed over to him the government of the kingdom in order to prepare for the invasion of Ceuta. More used to hunting, Duarte found ten months of the sedentary lifestyle and constant routines of government very difficult to bear “and the sadness began to grow, not about anything in particular but about any situation that arose or about some fantasies without reason.” He then had to endure an outbreak of plague and watch many people die around him. Duarte fell ill and became convinced he would die.

He recovered but was left with a great fear of death, not just of plague but of death in general and what happened afterwards, which of course he knew was sinful doubt. These thoughts over the next six months “took away all pleasure and caused in my opinion the greatest sadness that one could feel.” This episode ended with the death from plague of his mother Philippa of Lancaster in 1415. Her pious death brought him to his senses and caused him to stop fretting about the brevity of this life and reminded him of the glory of the next life.12

Duarte believed that the best treatment for melancholy was proper religious observation or, as he put it, “firmness of faith.” In the worst cases, which could lead to self-harm and suicide, the person should feel contrition, confess at length and go to communion with the greatest cleanness and humility, but should avoid weakening fasts and other religious ceremonies and should not be left alone.13 He came to realize that he himself suffered from both “illness and temptation of the Enemy.” It was a physical illness because it was caused by imbalance in one of the four humours, black bile (“melancholy” derives from the Greek for black bile or choler), but it was also a spiritual illness, the result of the sin of anger brought on by diabolical temptation, since Duarte saw sadness as a form of self-hatred.14

Thus proper understanding of the principles of religious faith, regular access to the sacraments, being able to recognize the seven sins and being able to practise the seven virtues would allow one to keep spiritually healthy. In fact, Duarte began to see his illness as a divine method “to amend my sins and failings.”15 Both his spiritual and physical health required him to have a worth-while occupation; idleness could lead to sadness and despair. Although Duarte did not link his own illness to the sin of sloth, he emphasised that his reading and writing were not laziness but a useful way to relax.16 He believed that one cause of his illness had been overwork and he guarded against this afterwards through periods of rest, exercise and therapeutic study. It is this practical manipulation of lifestyle that is the central focus of the present study.

King Duarte’s philosophical and religious thoughts have long been the subject of scholarly analysis, but his practical application of theory has been greatly neglected. In addition to improving his religious education and occupying his mind and body, Duarte went out of his way to avoid plague for the rest of his life, providing us with the earliest account of plague management in Portugal.17 He collected recipes specifically against plague and other ailments in the Book of Advice, and seems to have monitored his food and drink, if we can accept the evidence of the regimina that he copied. Yet this behaviour has in the past been dismissed as hypochondriac rather than intimately linked to Duarte’s understanding of theology and politics.18 It is possible to see the Loyal Counsellor as a practical application of theory in its own right; both as a form of occupational therapy and as a serious attempt to pass on lessons learned for the benefit of the realm.

Duarte’s prologue and final chapter made his purpose clear. He explained in the prologue that he had written an “ABC of loyalty made principally for the lords and people of their households” to teach them A: so that they can understand the forces and passions that are in each one of us, and B: the great good that followers of goodness and the virtues can attain; and C, concerning the correction of our evils and sins.19 In the final chapter, the king explained that this ABC of loyalty was divided into three parts: the individual’s body and soul; the household (including marital relations, family, servants and property); and the kingdom and city or other territory: “through loyalty all these receive great aid towards being well-governed.”20 The link between human passions, including pathological conditions such as melancholy, and royal government was made explicit here. Duarte claimed to practise what he preached within his own family and seems to have believed strongly that by maintaining spiritual and physical well-being through faithful adherence to his own advice he could avoid future disorder in his own mind, amongst his courtiers and across the kingdom. It is only by understanding Duarte’s disordered health that we can begin to understand his understanding of political order.

King Duarte’s Writings in Courtly Context

On the surface the Loyal Counsellor is a treatise on the seven sins, the three theological virtues (faith, hope and love) and the four cardinal virtues ( justice, temperance, prudence and fortitude), but the obvious order of discussion is often interrupted with moralistic stories. The last fourteen chapters of the book seem completely random: long quotations from theological or classical texts, a detailed regimen for the stomach and two chapters on how to organize the royal chapel.21 In the regimen, the king returned to the theme of appropriate eating and drinking which he had commented on throughout the text.22

In the chapters on the chapel he advised that the members of the royal choir should know the songs they are singing; they should not sing too high or laugh or joke; and they should pronounce words properly. He provided instructions for the education of choir boys and a duty rota for the clergy which are amongst the most detailed for medieval Europe.23 Yet although individually interesting, these pieces of advice are difficult to comprehend as part of a coherent pro-gramme of writing. However, if we think of Duarte’s digressions as lengthy footnotes to his discussion of the sins and virtues, and view everything after chapter 72 as a commentary on how to live according to the doctrine of contentamento, and everything after chapter 91 as appendices, we can see how Duarte envisaged the text: “a single treatise with some additions.”24

Duarte’s writings might seem unusual but they do belong to a clear courtly context. Since at least the twelfth century, there had developed a rich Fürstenspiegel or “Mirror of Princes” tradition: advice literature produced by courtiers for the edification and education of kings and their nobles. One of the most popular of these, the Secret of Secrets, was believed to have classical roots as a guide written by Aristotle for his pupil Alexander the Great, although it was originally written in Arabic in the ninth century and translated into Latin in the twelfth century.25 A fifteenth-century Portuguese translation still survives, associated with Duarte’s brother Henrique who either translated it or commissioned its translation. Duarte cited the Secret of Secrets regularly and listed it as one of the works in his library.26 It is probably the main model for the Loyal Counsellor.

Duarte borrowed the Pseudo-Aristotelian mixture of political and health advice and combined it with theology to create a treatise on good behaviour. Duarte also referred to two other popular guides to courtly behaviour: the Policraticus of John of Salisbury (d. 1180) and the Regimen of Princes of Giles of Rome (d. 1316).27 Duarte’s careful interpretation of all these works causes Steven Williams to argue that Duarte is one of the few rulers who can be shown to have read these guides. Most princes had them in their libraries but it is sometimes difficult to know how much notice they took of them.28

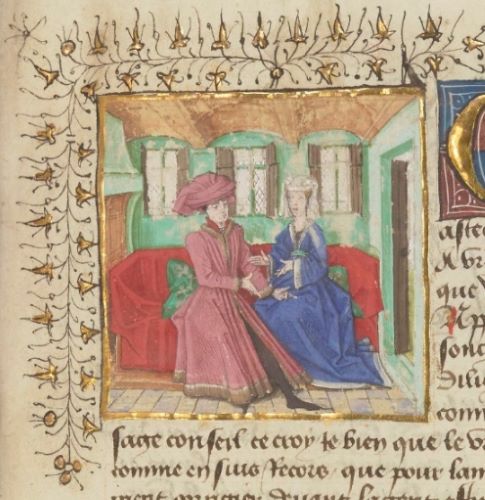

The main difference between these other Mirrors for Princes and the Loyal Counsellor is that Duarte was not listening to the advice of courtiers written for his edification, but offering his own advice to them. Although the book was written at the request of his wife, Leonor, it is clear that she was not the target audience: “it seems to me that this treatise should pertain principally to the men of the court so that they can know something similar of knowledge and desire to live virtuously.”29 Duarte wrote little specifically for women; his marital advice was for both men and women.30

In giving courtly and religious advice, Duarte may have had a familial model to follow. His English great-grandfather Henry of Lancaster (d. 1361) wrote a treatise on the seven sins in the 1350s which made use of a rich medical vocabulary and drew on courtly and military experience. Although there is no evidence that a manuscript of this work was brought to Portugal (Henry’s grand-daughter Philippa married João I in 1386 and continued to patronise English writers), the tone of the works is similar.31 There is nothing, however, that perfectly matches the form Duarte gave his work. Not only was the king giving both religious and political advice himself, but he was combining it with domestic experience that is unique at his social level. There are similar compilations written by English gentry or Italian or French merchants; the closest parallel is the household book known as the Ménagier de Paris, replete with moral treatises, equestrian, gardening and household advice and cooking recipes; however, this kind of compilation was not elsewhere produced by kings.32

The Ménagier of Paris and both of Duarte’s works: the Loyal Counsellor and the Book of Advice, are versions of what modern scholars refer to as the “Commonplace Book.” Early-modernists characterize these books as carefully compiled collections of literary quotations with a didactic or improving purpose. They were usually well-ordered, generic, sometimes professionally copied manuscripts that were often printed for widespread use.33 Medievalists, however, usually use the term “Commonplace Book” to refer to miscellanies that were roughly written, disorganized and highly personal manuscripts. They contained random items such as recipes, charms, financial accounts, lists and material of an almanac nature, all compiled over a period of time. They are likely to have been only for individual or household use.34

King Duarte’s Book of Advice seems to fit the latter model due to its mixed and personal contents. It contains many important letters that historians have used for generations to reconstruct key political events such as the invasion of Tangiers in 1437. The famous “Letter from Bruges” written by Duarte’s brother Pedro, Duke of Coimbra, while on his extensive travels in northern Europe, advises Duarte on how he should reform the university, regulate the clergy and handle the different estates of the kingdom, thus shedding light on religious and intellectual culture in Portugal during the 1420s. Duarte also recorded the precise dates of birth of his children, the measurements of the royal chambers in the palace of Sintra, the first surviving version of the Lord’s Prayer in Portuguese, a short chronicle of Portugal, some recipes and a few household accounts, particularly relating to almsgiving. Unfortunately as the original manuscript does not survive, there is no way of knowing the original order of contents or the original handwriting. It is not therefore known if it was a multi-authored collection made up of inserted strips of paper or parchment, or a collection of notebooks on different themes only later bound together. The chronicler Rui de Pina suggested the latter as he referred to the king’s habit of writing things down in a book, but Pina was not an eye-witness.35

In contrast, the Loyal Counsellor could be said to have parallels with the much more formal literary compilations of the early-modern period. It was written for the benefit of a specific audience with a clear moral and didactic purpose and it survives in a high-status manuscript, very uniform in production. Yet the Loyal Counsellor retains the highly personalized and familial content of a medieval miscellany. Even if it lacks the letters and household accounts, it still refers frequently to personal experience and family members. It shares numerous sections in common with the Book of Advice, such as the regimen for the stomach.36

Another piece of advice that Duarte repeated in both texts was guidance written for his brother Pedro on how to keep well while away from home.37 In the Loyal Counsellor this was included as part of Duarte’s discussion of sadness; he is trying to help his brother avoid homesickness. In the following chapter Duarte then went on to discuss these emotions in more detail, famously providing the first description of saudade, the quintessentially Portuguese emotion of bittersweet nostalgia poured out in thousands of letters from homesick migrant workers and colonial émigrés and now a cornerstone of Portuguese national identity.38 Duarte thus provided the first description, if not the first known mention, of a word in the Portuguese language, even if there is no direct evidence for the impact of the single manuscript of the Loyal Counsellor on Portuguese culture. As an emotion, saudade arose from a failure to be satisfied or content with one’s lot. Contentamento was another word that may have first appeared in the Book of Advice and then the Loyal Counsellor as a prudent way of life. The next section of this essay explores Duarte’s under-standing of how people should be satisfied with their lives, achieving well-being through contented well-ordered living. Unlike many of the Mirrors and courtesy guides discussed above, Duarte’s writings ultimately advised that householder, king and country should strive to be content and thereby happy.

Health and Well-Being: ‘Contentamento’ and the Six Non-Naturals

Contentamento is perhaps as close as we can get to a late-medieval concept of well-being. The wealth of historiography on medicine rarely defines either “health” or “well-being.”39 It focuses perhaps naturally on concepts of “illness” and “disease.” Yet modern debates about the World Health Organization’s definition of health first promulgated in 1948 (“Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”) suggest that both “health” and “well-being” deserve historical analysis as linguistic, legal and experiential concepts. The problem with the WHO’s definition is that it does not determine who decides whether one is in this state of complete well-being or what determines this seemingly impossible state which seems closer to that of “happiness” than “health.”40

The history of medicine has long been a history of power: the power of doc-tors, institutions and states over the personal lives and happiness of individuals. Healthcare and hygiene practices are not always matters of individual choice.41 Therefore, King Duarte’s understanding of contentamento from the perspective of a man able to regulate public health and medical institutions at a very early stage of their development, tells us something about how individual and communal responsibilities for health were initially constructed.42

For King Duarte, contentamento was a practical rather than an ideal way of life, to which he devoted three chapters in the Loyal Counsellor.43 It was based on the observation that nobody could be perfect, only God; elsewhere in the text he noted that even the apostles varied depending on their complexion, age and the alignment of planets at their birth.44 The fundamental principle of Duarte’s viewpoint, as outlined in an introduction to the section on the sins and virtues, was that everybody rich and poor should “always be content with what they have.” They should practise humility and patience and always try to do good.45 Later, the king explained that those who lacked fortitude, who always complained about things that had gone wrong and felt envy and anger should beware that “they did not fall into continuous sadness, disdain, disordered thought and desperation.”46 Those who had done well in life needed reminding that fortune could take it all away from them lest they become guilty of vainglory and ingratitude.47 Duarte argued that all men have the birth and natural disposition that God had granted; they should not feel self-satisfied but remember that even the poor can be rich through contentment: “those who have little to eat or drink and not enough sleep live in abundance.”48

Duarte’s ideas seem to have evolved from his understanding of the three theological and four cardinal virtues, especially prudence. The word “content,” meaning “satisfied” appeared in the English language at the beginning of the fifteenth century, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. In English and in most Romance languages, “being content” derives from the past participle of Latin continere and meant “to be contained” or “restrained” in one’s will and emotions.49 For Duarte therefore, being content seems to have meant practising prudence and temperance, enduring hardship though fortitude and defer-ring to divine justice. Duarte knew from original works of Aristotle and the Secret of Secrets that a good ruler should apply prudence and self-control to himself before he could do so effectively for others.50

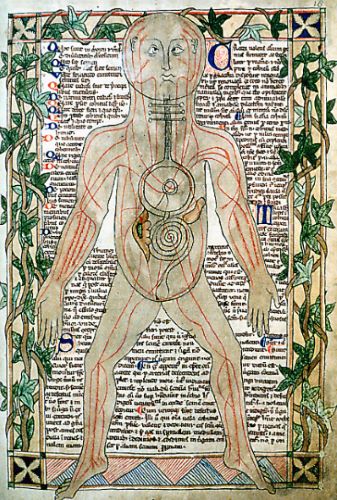

It is therefore valid to define Duarte’s concept of contentment as a type of well-being because of the prudent healthy lifestyle it promoted both in mind and body. Duarte believed that melancholy began as dissatisfaction with one’s lot and ended in despair as a result of not accepting divine justice. Melancholy signified a lack of fortitude and temperance in dealing with both good and bad fortune and it could lead to sinful, intemperate living. Duarte also understood melancholy to be a medical problem caused by excess of black bile.51 He seems to have absorbed a great deal of Graeco-Arabic medical theory about the body, although he did not attribute it to any one authority. For Duarte the way to maintain self-discipline in one’s lifestyle, and thereby practise prudence and seek contentment, was to manipulate what his physicians would have called the six non-naturals: air, food and drink, exercise and rest, sleep and wakefulness, repletion and excretion and the accidents or passions of the soul i.e. the emotions.52

In all these respects Duarte’s advice was no different to that of many other European regimina or consilia. The difference, as pointed out earlier, was that he was doing the advising rather than being advised by a humble courtier. Duarte did not always accept the advice of his physicians, preferring at times that of friends, councillors, his confessor and the divine Physician. However, in most matters of regimen he deferred to medical opinion.53 The last section of this essay will consider how Duarte manipulated advice on the six non-naturals, focusing on food, drink and sex.

King Duarte’s Relationship with Food, Drink, and Sex

Focusing on Duarte’s attitude to food and drink sets up the same limitation as in other studies of Regimen Sanitatis literature.54 Although food and drink usually form the largest section of the regimina, some of the other non-naturals, especially excretion, sleep and exercise, get relatively little attention. The problem with isolating individual elements is that it undermines the concept of healthy lifestyle as understood in the Middle Ages, and makes it difficult to explore the reception of the six non-naturals as an idea that went beyond the court. Peregrine Horden is one of the few to argue that the six things featured prominently in hospital regulations and therefore affected the poor as well as the rich.55 Too great a focus on elite advice texts obscures wider application of theory.

For example, Duarte’s obsessive ordering of his chapel might suggest that the liturgy had a therapeutic affect on him. Medieval texts usually cite musical instruments rather than singing as therapeutic, but Horden has argued that hearing the singing could also have been understood to impact on emotional health as part of the system of the non-naturals.56 Duarte never talked about liking music for itself, but his emphasis on a well-trained choir may relate to his need for regular liturgical solace. Nevertheless, food and drink are familiar topics to a modern audience so will be focused on here for reasons of space, along with sex, as long as it is remembered that food and drink on their own were not enough to maintain well-being.

The majority of Duarte’s dietary advice in the Loyal Counsellor appears in the chapters on melancholy (19 and 20), his chapter on the sin of gluttony (32) followed by a contrasting one on fasting (33) and the regimen for the stomach (100).57 Briefer comments on appropriate eating and drinking are interspersed throughout. As pointed out earlier, the regimen for the stomach also appears in the Book of Advice along with several other regimina and recipes. Some of these recipes blur the line between food and medicine, thus contributing to a continuing debate amongst historians over the relationship between them.58 For example, in the Book of Advice Duarte included a recipe for pos do duque or “duke’s powders,” a mixture of ginger, cinnamon, galingal, zedoary, grains of paradise, long pepper, nutmeg and mace.59 This recipe may correlate with the sweet powder (poudre douce) frequently used in English and French cook-books to contrast with the sharper poudre fort.60 However, Johanna van Winter points out that there was a Duke’s Powder, probably named after the Doge of Venice because of the link between Venice and the spice trade. The problem is that poudre douce should not have pepper in it, whereas Duke’s Powder requires sugar. Neither contain the very unusual ingredient zedoary (a rhizome similar to turmeric).61 It is possible that the addition of this substance turned the recipe into a medicine.

Many of Duarte’s more complicated recipes include exotic spices that were equally at home in the kitchen or the apothecary’s, to the extent that studies of the few household inventories and account books to survive from late medieval Portugal cannot determine what they were used for most of the time.62 The earliest Portuguese cookbook survives in a sixteenth-century manuscript, so Duarte’s recipes are amongst the only guides to earlier usage of spices.63 His most famous recipe represents both the range of available ingredients and the king’s desperation for health. Duarte’s councillor Diogo Afonso de Mangancha, a doctor in canon and civil law rather than medicine, sent him from Italy a recipe and associated regimen against plague which involved force-feeding a badger with a drink of pearls, coral, gold, white wine and camphor, killing it, grinding up its primary organs, mixing them with the animal’s blood and with cinnamon, gentian, verbena, ginger, cloves, myrrh, aloes and unicorn horn, and drying it all into a powder to be drunk in water and vinegar.64

It is details such as this that make Duarte’s advice unique. Otherwise, much of what he says about food and drink is very similar to the guidance in his sources, especially the Secret of Secrets and the many theological works he read on the seven sins. Thanks to works like these there was a long tradition in European courtly literature relating gluttony and excess to a lack of prudence; those who overate or got drunk were inherently bad kings. This should be how we interpret the reports of hostile chroniclers that Kings Henry II (d. 1135) and John of England (d. 1216) died from over-eating lampreys and peaches respectively. Both were thought to be cold, moist foods that had to be eaten rarely and in careful balance with the rest of the meal. Eating them in excess, and especially against the explicit advice of a physician as was the case with Henry II, underlined the kings’ ineffective self-control and by extension their inability to govern the realm properly.65

Strong, effective kings, like Louis IX of France (d. 1270), mixed their wine with water in order to avoid gout, stomach problems and drunkenness: “it was too revolting a thing for any brave man to be in such a state.” Louis always ate “with good grace whatever his cooks had prepared to set before him.”66 On the other hand, there was an equally long medical tradition of having to justify royal tastes for unsuitable foods. In the ninth century, Einhard wrote that the Emperor Charlemagne insisted on eating roast meats against medical advice, though he drank alcohol sparingly; in the early-fourteenth century, King Robert of Scotland’s taste for lampreys horrified his Italian physician.67

Duarte therefore understood that what he ate had moral significance, although he did not slavishly follow medical advice. Like other authors, Duarte counselled against the eating of moist things like cherries, peaches and oysters, the fatty parts of fish and meat and cold sharp things like vinegar and lemon.68 Yet we should not make the mistake of so many food historians that rich people in the Middle Ages ate no fruit or vegetables.69 Duarte assumed that people would still eat these foods, advising a twice yearly purge, once in spring to get rid of the superfluities caused by eating fish during Lent and once in the autumn because of the fruit (he did not otherwise approve of purging and bloodletting for the healthy).70 Duarte also selected carefully from available regimina, only choosing one from the Book of Advice to copy into the Loyal Counsellor. For example, he did not choose a regimen which does indeed advise an almost entirely meat-based diet, with very little vegetable pottage and lots of toasted bread and sugary drinks.71

Duarte’s chosen regimen appears to have been more balanced, designed for a lifestyle where drinking late, staying up all night or getting up early were sometimes unavoidable duties. He followed Pseudo-Aristotle’s observation that it was better to eat to live than to live to eat.72 For him, there was more pleasure in moderate and contented i.e. satisfied eating, than there was in eating purely for pleasure. Duarte argued that those of royal estate had to set an example for others, who “if they governed themselves reasonably in as far as their persons were concerned, did less well in the regimen of their households and communities.” In fact, it was particularly difficult for the Portuguese to avoid gluttony “because we live in a land most abundant with food and drink.”73 The link between good diet and good government here is explicit.

Duarte viewed his spiritual and physical health as inextricably entwined. Maintaining a healthy body could prevent the occurrence of sin; observing medical advice generally enabled a well-ordered life. Even excessive fasting could lead to disorder of the body and it smacked of the sin of pride.74 The most important connection between body and soul for Duarte was warding off melancholy. He took “common pills” whenever he felt his sadness start to return and also took them regularly for his stomach. His recipes indicate that these pills contained myrrh, aloes, bugloss and saffron. He also collected several recipes for corrença, which could be translated as “the runs” or diarrhoea.75

All these references suggest that Duarte might have had some kind of stress-related problem that we could call irritable bowel syndrome and earlier authorities saw as a physical condition described as hypochondriasis (it did not imply malingering until the eighteenth century).76 The conjunction between Duarte’s normative advice and the recipes suggests that he practised what he preached, albeit on his own terms. He tells us for example that he rejected medical advice to give up his duties, have sex and drink undiluted wine. Duarte refused to give up the task of governing Portugal, saying that nobody actually noticed any change in his behaviour (unfortunately something that cannot be verified independently). He argued that alcohol could not solve the problem. It lessened the torment but “where they thought to cure the illness, they fell into the servitude of drunkenness through which many souls and bodies and livelihoods had been lost.”77

Later in the chapter on gluttony Duarte returned to this theme, explaining that drinking too much alcohol was bad, referring to his experience that women and Muslims “in this land” drank water instead and as a consequence “lived to a great age and generally are healthier than those who drink wine.”78 Duarte thus reinforced traditional narratives of gluttony and prudence with his own observations of life in Portugal. One wonders, however, why Duarte’s doctors originally advised him in such a way, since sex and wine sound much more like the standard treatment for the particular form of melancholy known as love-sickness.79 Duarte’s own views seem more in line with those of the Italian physician Gentile da Foligno (d. 1348) in a consilia that he wrote for a naturally melancholic patient. Gentile similarly advocated the avoidance of sex, advised that wine should be watered down and warned against sharp foods, fresh fruit and most raw vegetables, although he did advise removing the patient from the anxieties of daily life.80 One wonders if these contrasting treatments were the result of differences between Portuguese and Italian medical practice (Duarte may have been influenced by Italian practices through his widely-travelled family members or courtiers), or whether there was some-thing else going on in the king’s mind.

Duarte’s refusal to have sex as a cure was once seen by Portuguese historians as bizarre. Together with his late marriage and his close relationship with his mother, the crisis in his illness occurring because of her death, he has been diagnosed as having an oedipal complex. Philippa of Lancaster’s piety was blamed for her son’s sexual repression.81 It seems all to be nonsense: Duarte married late because it took years to negotiate his marriage; in fact his father refused to attend the wedding in 1428 because the match was so controversial. Moreover, Duarte was probably influenced by the story of chaste Sir Galahad, whose story was in his library, and the knights of the Round Table more generally (he belonged to the English Order of the Garter).82 Finally, Duarte was exactly the ideal age prescribed by Aristotle’s Politics for the marriage of men.83 There is no need to turn to psychoanalysis to understand this prince. Nevertheless, one cannot help but wonder whether the medical advice given to the young Duarte represented a diagnosis that in his later years he refused to acknowledge.

During the ten years of their marriage Duarte and his wife Leonor had nine children at intervals of between ten and thirteen months, except for a last posthumous baby.84 Leonor in fact gave birth twice in 1432, perhaps prompting Duarte to record a recipe for sore breasts after birth.85 She appears to have been a suitably harmonious partner for the king, causing him to write that the love of a good, wise, attractive and gracious wife was “a great remedy against sadness and boredom.”86 This suggestive comment indicates that sex itself was not a problem for Duarte as long as it was engaged in moderately, contentedly and without sin. Coitus was part of the system of the non-naturals, usually included under excretion or emotions. Both too much sex and too little were thought to be unhealthy.87 Duarte could manipulate his sexual activity as he did his sleep (which he recognized was lacking while suffering from melancholy) and his exercise (as pointed out earlier periods of relaxing were essential to his recovery).88 However, as far as coitus was concerned he had to wait until he was married as lust and fornication were sins.

If Duarte had always thought this, it is not impossible that his physicians believed that lovesickness (or lack of sexual outlet) might have been the cause of his youthful malady. On the other hand, Duarte related the sins of lust and gluttony quite closely to each other as excesses of old age not youth.89 In contrast love-sickness was barely mentioned as part of the sin of anger, resulting from unsatisfied passion.90 Duarte believed that love should depend on liking, a wish to do good to each other, desire and friendship. Desire without the three other things caused jealousy, pride and sadness born of dissatisfaction with the other person. Duarte argued that “we are not looking for perfection in the people we love: let us be content with their loyalty and affection.” Joy (ledice) stems from a couple’s contentment with each other’s goodness and virtues.91 Instead of seeing Duarte’s chastity as a cause of illness, we should see it as a sign that he lived according to his own advice.

Conclusion

One should not go away thinking that Duarte was emotionally repressed. The whole point of writing his texts was to understand his emotions and put them in order to that he could avoid sin and illness. Duarte’s understanding was that body and soul were intimately connected. Curing melancholy involved spiritual and medical measures. On a spiritual level, Duarte seems to have ordered his chapel so that he could maintain his devotions properly despite the itinerancy of the court or his own failings. He might not have wanted the choirboys to be cracking jokes in their pews, but joy and cheerfulness were important goals for him, to be achieved without recourse to wine. Love of pleasure was sinful but pleasure was not itself sinful and listening to the liturgy could be pleasurable; it tends to be modern people who see Duarte’s two hours a day at mass as a burden.92

On a medical level, cheerfulness and joy could both be achieved through the practice of a careful well-ordered lifestyle, balancing the six non-naturals and avoiding extremes of passion. Duarte’s aim was to achieve order on three levels, that of the individual, the household and the kingdom, something that he hoped he could achieve by maintaining his own spiritual and physical health and inspiring others to follow his lead through his writings. Although much of what King Duarte wrote about health was not original, his doctrine of contentamento as a fusion of religious and classical advice on well-being seems to have been unique. If Duarte had not died prematurely in 1438 he would per-haps have been remembered not as a sad king and political failure, but as a strong, successful and happy monarch.93

Endnotes

- The research for this paper was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant no. 076812). An earlier version of the paper was presented at the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo in 2010 in a session sponsored by Medica. I would like to thank Sari Katajala-Peltomaa for inviting me to participate in this volume. Finally, thanks to Axel Műller for everything.

- Takashi Shogimen, “‘Head or Heart?’ Revisited: Physiology and Political Thought in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries,” History of Political Thought 28 (2007).

- Bernard Guenée, La folie de Charles VI: Roi Bien-Aimé (Paris: Perrin, 2004); Carole Rawcliffe, “The Insanity of Henry VI,” The Historian 50 (1996); Wendy Turner, “A Cure for the King Means Health for the Country: The Mental and Physical Health of Henry VI,” in Madness in Medieval Law and Custom, ed. Wendy Turner (Leiden: Brill, 2010); Cory James Rushton, “The King’s Stupor: Dealing with Royal Paralysis in Late Medieval England,” in Madness in Medieval Law and Custom; Douglas Biggs, “The Politics of Health: Henry IV and the Long Parliament of 1406,” in Henry IV: The Establishment of the Regime, 1399–1406, ed. Gwilym Dodd and Douglas Biggs (Woodbridge: York Medieval Press, 2003); Bernard Hamilton, The Leper King and His Heirs: Baldwin IV and the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

- Duarte of Portugal, Leal Conselheiro, ed. Maria Helena Lopes de Castro (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional/Casa da Moeda, 1998), 208 [referred to hereafter as LC].

- The manuscript, first catalogued in the French royal library in 1544, may have passed into the Aragonese royal library in Naples via Duarte’s widow Leonor of Aragon and then seized after the French invasion of Naples in 1495: LC, xvii–xviii. See also Rui de Pina, Crónicas, ed. Manuel Lopes de Almeida (Oporto: Lello & Irmão, 1977), 495. The manuscript also contains an equestrian manual composed by the king.

- João José Alves Dias, ed., Livro dos Conselhos de el-Rei D. Duarte (Livro da Cartuxa) (Lisbon: Editorial Estampa, 1982) [hereafter referred to as BA].

- Iona McCleery, “Both ‘Illness and Temptation of the Enemy’: Melancholy, the Medieval Patient and the Writings of King Duarte of Portugal (r. 1433–38),” Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 1: 2 (2009).

- Peter Russell, Prince Henry ‘the Navigator’: A Life (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000); Monique Sommé, Isabelle de Portugal, Duchesse de Bourgogne: Une femme du pouvoir au XVe siècle (Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 1998); Anthony Disney, The History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- Pina, Crónicas, 573. Revisionist scholarship on Duarte began with Domingos M.G. dos Santos, D. Duarte e as Responsabilidades de Tânger (1433–1438) (Lisbon: Comissão Executiva do V Centenário da Morte do Infante D. Henrique, 1960). The most recent biography is Luís Miguel Duarte, D. Duarte: Requiem por um Rei Triste (Lisbon: Círculo de Leitores, 2005).

- Joaquim Pedro de Oliveira Martins, Os Filhos de D. João I (1st publ. 1891; Lisbon: Guimarães Editores, 1993), 134.

- Iona McCleery, “Medical ‘Emplotment’ and Plotting Medicine: Health and Disease in Late Medieval Portuguese Chronicles,” Social History of Medicine 24 (2011).

- LC, 73–76.

- LC, 81, 86–87.

- LC, 66, 75.

- LC, 76.

- LC, 109–111.

- LC, 219–224.

- Júlio Dantas, “A Neurastenia do Rei D. Duarte,” in Júlio Dantas, Outros Tempos (Lisbon: A.M. Teixeira, 1909); Carlos Amaral Dias, “D. Duarte e a Depressão,” Revista Portuguesa de Psicanálise 1 (1985); Yvonne David-Peyre, “Neurasthénie et croyance chez D. Duarte de Portugal,” Arquivo do Centro Cultural Português 15 (1980); Faria de Vasconcelos, “Contribuição para o Estudo da Psicologia de D. Duarte,” Brotéria 25 (1937).

- LC, 8–9.

- LC, 373–375.

- On Duarte’s sources, see Duarte, D. Duarte, ch. 14; João Dionísio, “Dom Duarte, Leitor de Cassiano,” (Lisbon: University of Lisbon, Ph.D. dissertation, 2000); João Dionísio, “D. Duarte e a Leitura,” Revista da Biblioteca Nacional 6 (1991); Susana Fernandes Videira, “As Ideias Políticas do Rei D. Duarte (Algumas Considerações),” in Estudos em Homenagem ao Professor Doutor Raúl Ventura, ed. José de Oliveira Ascensão (Lisbon: Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Lisboa/Coimbra Editora, 2003).

- LC, 367–370.

- LC, 342–348; Rita Costa Gomes, “The Royal Chapel in Iberia: Models, Contexts and Influences,” The Medieval History Journal 12 (2003).

- LC, 7.

- Steven Williams, The Secret of Secrets: The Scholarly Career of a Pseudo-Aristotelian Text in the Latin Middle Ages (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003).

- Artur Moreira de Sá, ed., Segredo dos Segredos: Tradução Portugûes Segundo um Manuscrito Inédito do Século XV (Lisbon: Universidade de Lisboa, 1960); BA, 206–208; LC, 202–204.

- LC, 124, 128, 140, 200, 204, 206–207, 209; Charles F. Briggs, Giles of Rome’s De Regimine Principium: Reading and Writing Politics at Court and University, c. 1275–c. 1525 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); John of Salisbury, Policraticus: Of the Frivolities of Courtiers and the Footprints of Philosophers, ed. Cary J. Nederman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- Steven Williams, “Giving Advice and Taking It: The Reception by Rulers of the Pseudo–Aristotelian Secretum Secretorum as a Speculum Principis,” in Consilium: Teorie e pratiche del consiliare nella cultura medievale, ed. Carla Casagrande, Chiara Crisciani and Silvana Vecchio (Florence: Sismel, 2004); Judith Ferster, Fictions of Advice: The Literature and Politics of Counsel in Late Medieval England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996); Marilyn Nicoud, Les régimes de santé au Moyen Âge: naissance et diffusion d’une écriture médicale (XIIIe–XVe siècle) (Rome: École française de Rome, 2007).

- LC, 11.

- LC, 177.

- Henry, Duke of Lancaster, Le Livre de Seyntz Medecines, ed. Emil Arnould (Oxford: Blackwell, 1940); Joyce Coleman, “Philippa of Lancaster, Queen of Portugal: and Patron of the Gower Translations?” in England and Iberia in the Middle Ages, 12th–15th Century: Cultural, Literary, and Political Changes, ed. María Bullón-Fernández (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

- Gina Greco and Christine Rose, trans., The Good Wife’s Guide: Le Ménagier de Paris, A Medieval Household Book (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2009).

- Ann Moss, Printed Commonplace Books and the Structuring of Renaissance Thought (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996).

- Deborah Youngs, “The Late Medieval Commonplace Book: The Example of the Commonplace Book of Humphrey Newton of Newton and Pownall, Cheshire (1466–1536),” Archives 25 (2000); David Parker, “The Importance of the Commonplace Book: London, 1450–1550,” Manuscripta 40 (1996); Julia Boffey, “Bodleian Library, MS Arch. Selden. B.24 and Definitions of the ‘Household Book’,” in The English Medieval Book: Studies in Memory of Jeremy Griffiths, ed. Anthony Edwards, Vincent Gillespie and Ralph Hanna (London: British Library, 2000), and Julia Boffey and John Thompson, “Anthologies and Miscellanies: Production and the Choice of Texts,” in Book Production and Publishing in Britain, 1375–1475, ed. Jeremy Griffiths and Derek Pearsall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

- Pina, Crónicas, 498.

- LC, 349–361, 367–370; BA, 100–113, 253–256.

- LC, 91–96; BA, 21–26.

- Eduardo Lourenço, O Labirinto da Saudade: Psicanálise Mítica do Destino Português, 4th ed. (Lisbon: Publicações Dom Quixote, 1991); Afonso Botelho, Da Saudade ao Saudo-sismo (Lisbon: Instituto de Cultura e Língua Portuguesa, Minstério da Educação, 1990).

- Klaus Bergdolt, Wellbeing: A Cultural History of Healthy Living, trans. Jane Dewhurst (Cambridge: Polity, 2008); Maaike van der Lugt, “Neither Ill Nor Healthy: The Intermediate State Between Health and Disease in Medieval Medicine,” Quaderni Storici 136 (2011); Nicoud, Régimes de Santé, I: 7–9, 316–319.

- Rodolfo Saracci, “The World Health Organisation Needs to Reconsider its Definition of Health,” British Medical Journal 314 (1997); Niyi Awofeso, “Redefining Health,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/bulletin/bulletin_board/83/ustun11051/en/ (accessed 5 December 2011); Alejandro Jadad and Laura O’Grady, “How Should Health Be Defined?” British Medical Journal 337 (2008).

- John Pickstone, “Medicine, Society and the State,” in The Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine, ed. Roy Porter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); John Burnham, What is Medical History? (Cambridge: Polity, 2005).

- For evidence of medical licensing in this period, see Iria Gonçalves, “Físicos e Cirurgiões Quatrocentistas: As Cartas de Exame,” in Iria Gonçalves, Imagens do Mundo Medieval (Lisbon: Livros Horizonte, 1988).

- LC, 268–274.

- LC, 271, 85.

- LC, 45–47; BA, 7–10.

- LC, 274.

- LC, 269–270.

- LC, 273.

- “Content”, in The Oxford English Dictionary, prep. John Simpson and Edmund Weiner, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), III, 816.

- LC, 205.

- LC, 73.

- Luis García Ballester, “On the Origin of the ‘Six Non-Natural Things’ in Galen,” in Luis García Ballester, Galen and Galenism: Theory and Medical Practice from Antiquity to the European Renaissance (Aldershot: Ashgate [Variorum Reprints], 2002), article IV; Nicoud, Régimes de santé, I: 153–184.

- LC, 62, 150, 288; BA, 12. Many of the recipes in BA had ecclesiastical or bureaucratic origins.

- Nicoud, Régimes de santé; Melitta Weiss Adamson, Medieval Dietetics: Food and Drink in Regimen Sanitatis Literature from 800 to 1400 (Frankfurt-am-Main: Peter Lang, 1995).

- Peregrine Horden, “A Non-Natural Environment: Medicine Without Doctors and the Medieval European Hospital,” in The Medieval Hospital and Medical Practice, ed. Barbara Bowers (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007). See also Janna Coomans and Guy Geltner, “On the Street and in the Bathhouse: Medieval Galenism in Action?” Anuario de Estudios Medievales 43 (2013).

- Peregrine Horden, “Religion as Medicine: Music in Medieval Hospitals,” in Peter Biller and Joseph Ziegler, ed. Religion and Medicine in the Middle Ages (Woodbridge: York Medieval Press, 2001); Peter Murray Jones, “Music Therapy in the Later Middle Ages: The Case of Hugo van der Goes,” in Music as Medicine: the History of Music Therapy since Antiquity, ed. Peregrine Horden (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000).

- LC, 73–83, 125–132, 367–370.

- Bruno Laurioux, “Cuisine et Médecine au Moyen Âge: Alliées ou Ennemies?” Cahiers de Recherches Médiévales 13 (2006); Terence Scully, The Art of Cookery in the Middle Ages, new ed. (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2005), 41–53, 185–195; Ken Albala, Eating Right in the Renaissance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 241–283.

- BA, 271.

- For example, in the earliest English cookbook, the Forme of Cury, dating to c. 1390: Constance Hieatt and Sharon Butler, ed. Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century (London: Oxford University Press, 1985), 98–9, 208.

- Johanna van Winter, Spices and Comfits: Collected Papers on Medieval Food (Totnes: Prospect Books, 2007), 384, 387, note 14.

- Isabel dos Guimarães Sá and Lisbeth Rodrigues, “Sugar and Spices in Portuguese Renaissance Medicine,” Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies (forthcoming 2015).

- Giacinto Manuppella, ed., Livro de Cozinha da Infanta D. Maria: Códice Português I.E.33. da Biblioteca Nacional de Nápoles, new ed. (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional/Casa da Moeda, 1986).

- BA, 93–96, 276–277.

- Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum: The History of the English People, ed. Diana Greenway (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996), 491; Roger of Wendover, vol. 2 of Liber qui Dicitur Flores Historiarum, ed. Henry Hewlett (London: Longman, Rolls Series 84, 1886–1896), 196.

- Margaret Shaw, trans., Joinville and Villehardouin: Chronicles of the Crusades (London: Penguin, 1963), 167–168.

- Lewis Thorpe, trans., Einhard and Notker the Stammerer: Two Lives of Charlemagne (London: Penguin, 1969), 77–78; Caroline Proctor, “Physician to the Bruce: Maino De Maineri in Scotland,” Scottish Historical Review 86 (2007).

- LC, 367. Duarte’s regimen for the stomach can be read at my project website: http://www .leeds.ac.uk/yawya/history/medieval/King%20Duartes%20diet%20for%20the%20stomach.html (accessed 5 December 2011).

- Nicoud, Régimes de santé, I: 671–680; John Harvey, “Vegetables in the Middle Ages,” Garden History 12 (1984); Christopher Dyer, “Gardens and Garden Produce in the Later Middle Ages,” in Food in Medieval England: Diet and Nutrition, ed. Christopher Woolgar, Dale Serjeantson and Tony Waldron (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- LC, 370.

- BA, 268–269.

- Sá, ed. Segredo, 28; LC, 126.

- LC, 127, 128–129.

- LC, 131–132.

- LC, 80–81, 369; BA, 261–263, 258, 265, 272.

- Stanley Jackson, Melancholia and Depression: from Hippocratic Times to Modern Times (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986), 274–310. The link Duarte makes between his sadness and his stomach makes sense in both medieval and modern under-standing, but I prefer to use medieval terms. See Piers Mitchell, “Retrospective Diagnosis and the Use of Historical Texts for Investigating Disease in the Past,” Journal of International Palaeopathology 1 (2011).

- LC, 78.

- LC, 126.

- Mary Wack, Lovesickness in the Middle Ages: the Viaticum and its Commentaries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990).

- Faith Wallis, ed. Medieval Medicine: A Reader (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 411–413.

- Dias, “D. Duarte e a Depressão,” 81; Duarte, D. Duarte, 93.

- McCleery, “Both Illness and Temptation,” 168; Duarte, D. Duarte, 94–128.

- Peter Biller, The Measure of Multitude: Population in Medieval Thought (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 326–356.

- Most of these intervals can be determined from Duarte’s list of the births in BA, 146.

- BA, 257.

- LC, 90.

- Caroline Proctor, “Between Medicine and Morals: Sex in the Regimens of Maino de Maineri,” in Medieval Sexuality: A Casebook, ed. April Harper and Caroline Proctor (New York: Routledge, 2008); Danielle Jacquart and Claude Thomasset, Sexuality and Medicine in the Middle Ages, trans. Matthew Adamson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 116–138.

- LC, 80, 88–89.

- LC, 123–124.

- LC, 72.

- LC, 175, 197. See also Maria de Lurdes Correia Fernandes, “Da Doutrina à Vivência: Amor, Amizade e Casamento no Leal Conselheiro do Rei D. Duarte,” Revista da Faculdade de Letras: Línguas e Literaturas, 2nd series, 1 (1984).

- Duarte outlined his day in LC, 306.

- The chronicler Rui de Pina described Duarte as both sad and happy (alegre): Crónicas, 495.

Contribution (177-196) from Mental (Dis)Order in Later Medieval Europe, edited by Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Susanna Niiranen (Brill Academic Pub., 03.12.2014), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.