There is no other word in English as effectively dismissive as “puritan.”

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

American history is filled with stories of religiously minded people who have attempted to live their values in community with others. Some of these groups have been motivated to change the larger society, while others have focused their efforts on their own communities. This collection explores the contours and legacies of some of the nation’s most prominent religious movements.

Colonial New England

One Manner of Law

The religious origins of American liberalism.

After years of reading about the American Puritans, then reading the Puritans themselves, I am now convinced that our history could undergo a scrupulous reappraisal that would cause us to consider things in a radically new light. My work brought me to the subject obliquely, first through an attempt to contextualize the burst of very great literature that came out of New England in the nineteenth century, then through an attempt to understand the audience for whom Shakespeare wrote, those crowds of “groundlings” who have provided employment for legions of professors and journal editors by standing through performances of Hamlet and Lear.

In both cases the context can be called Puritanism—in Massachusetts, for obvious reasons; in prerevolutionary London, because the great political and religious controversies of the time played out in the sermons and pamphlets of dissenters and non-conformists, delivered to whomever could be reached in an increasingly literate public. Shakespeare’s histories dramatized Edward Hall, Raphael Holinshed, John Foxe, and other writers who addressed popular interest in the dynastic wars that lay behind the Tudor and Stuart regimes. I would be happy to defend the thesis that, in his treatment of this disastrous period, Shakespeare posed the crucial question of whether hereditary monarchy can produce legitimate government or fit and capable rulers. His conclusion, I would argue, is that it cannot. The crisis that England was approaching had everything to do with the legitimacy of monarchy itself. Persecutions under Mary I had sent dissenters to Geneva, where hereditary rulers had been expelled and the city governed as a republic since 1541. The Dutch had defeated Philip II and formed a republic in 1581, with the help of Englishmen who were sympathetic with the Dutch as fellow Calvinists.

This is all well known to students of the Reformation. Nevertheless, that nautical England, already strenuously involved in world affairs, would have no awareness of events on the continent, and of the ideas behind these events, is an assumption common to many interpretations of Elizabethan writers. It is nonsense to suggest, as some experts have, that Shakespeare could think only in terms of hierarchies and chains of being. But history has become so segmented that the English Renaissance and Reformation are treated as discrete phenomena, though they were perfectly simultaneous, and many writers and political figures important to both.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT HARPER’S MAGAZINE

Pranksters and Puritans

Why Thomas Morton seems to have taken particular delight in driving the Pilgrims and Puritans out of their minds.

Missing from the traditional Thanksgiving narrative—the brutal winter followed by the bountiful harvest—is the horrific epidemic that raged through the Native American community during the three years immediately preceding the 1620 arrival of the Mayflower. Rat feces on boot soles are believed to have carried lethal bacteria from European ships anchored along the New England coastline to Native villages. Whatever the precise nature of the disease, it worked with ruthless efficiency during the years 1616 to 1619. “The pace of death must have been terrifying,” Peter Mancall writes in The Trials of Thomas Morton, his book about a little-known chapter in the European settling of New England. “Most epidemics, even of highly contagious diseases like the plague, typically leave survivors. But this series of infections apparently killed almost everyone.” The Pilgrims regarded the “wonderfull Plague,” which decimated the Native farmers but left their cleared fields, as one more God-given thing to be thankful for.

Natives spared by the disease suffered another disaster in 1637, in what came to be known as the Pequot War but was more accurately a massacre. Colonists seized on various pretexts to slaughter 1,500 Natives in two months, including women and children in a village on the Mystic River that they deliberately torched. “It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fire,” the Pilgrim leader William Bradford wrote of the atrocity, “and the streams of blood quenching the same.” Again, Bradford thanked a providential God for aiding his men, “thus to enclose their enemies in their hands and give them so speedy a victory over so proud and insulting an enemy.”

But there were other challenges to the Pilgrims’ fragile utopian experiment, and to the more worldly and successful Puritan colony of Massachusetts Bay, founded in 1630, that eventually absorbed it. This threat arose from fellow Englishmen, many of whom regarded the Pilgrims, with their astringent separatist views that had taken them first to Holland and then to New England, and the more moderate Puritans, who wished to reform the abuses of the Anglican Church, with distaste.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK REVIEW

When Perry Miller Invented America

In a covenantal nation like the United States, words are the very ligaments that hold the body together, and what words we choose become everything.

I have now looked seriously at America from both sides, West and East, and wish to Hell this country could say what, in the realm of ideas, it means commensurate with its force.

Perry Miller in letter, September 14, 1952

Several days after the Allied invasion at Normandy, a Harvard historian and agent in the US Office of Strategic Services named Perry Miller went to survey the debris spread across those beaches that bore good American code names like “Omaha” and “Utah,” beaches where 10,000 troops had died. A gentle summer breeze rolled in, and Miller espied that fathomless line dotted with amphibious LCVPs, jeeps, and tanks. Along the shoals were thousands of waterlogged corpses, the ocean tide still dyed pink. He wrote home and described a dead man “looking terribly young, crunched into the side of the road, his hand clutching a grenade which he had not had time to cock, his rifle lying across his chest and on the butt of it, pasted on with adhesive tape, a picture of his girl — young and fresh and smiling.”

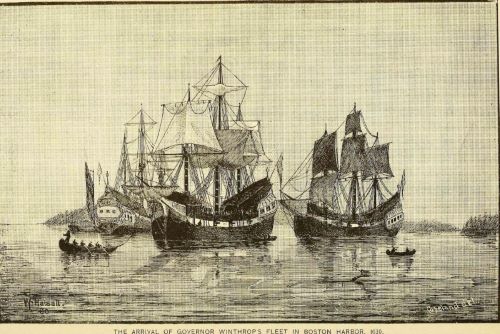

Miller was only 39, but some of the dead at Normandy were undoubtedly around the age of his students. At the time that he’d enlisted, Miller was already the author of two well-received monographs — Orthodoxy in Massachusetts, 1630–1650 (1933) and The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century (1939). The latter would become a classic of American studies, the first of several by Miller. I wonder if, on that beach, he didn’t ruminate on a reverse expedition that had departed just across the channel some 314 years earlier when the Arbella set sail for Boston, and onboard, the first governor of Massachusetts, John Winthrop, apocryphally sermonized that the Puritans must “make other’s conditions our own […] always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work.”

As World War II entered its final stage, the professor understood the United States to be in a battle between two civilizations. America and Nazi Germany each represented irreconcilable understandings, with both claiming an exceptionalism that deigned to speak for humanity. Hitler’s cankered vision was to be contrasted with Winthrop’s declaration in his 1630 lay sermon A Modell of Christian Charity, which claimed that we must “rejoice together, mourne together, labour and suffer together.” With the success of D-Day, Miller and others could already see that a coming conflict lay further to the east, so that Winthrop would soon have to figuratively challenge Stalin as he had Hitler. “Winthrop opened the story of America,” writes Abram C. Van Engen in his engaging new book City on a Hill: A History of American Exceptionalism, describing that contemporary myth which holds that the Puritan “called on us to serve as a beacon of liberty, chosen by God to spread the benefits of self-government, toleration, and free enterprise to the entire watching world.” In that fight, men like Miller were invaluable, for he and other scholars distilled an understanding of the United States’ history that none other than Stalin termed “American exceptionalism.” Much of the work that Miller did with the OSS, the administrative precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency, remains classified. It’s known, however, that he helped establish its psychological warfare division.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

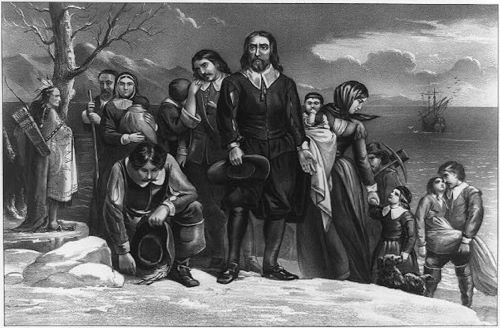

What Liberty Meant to the Pilgrims

Most adult men could aspire to participation in the religious and political government of the colony. But this communal liberty did not imply personal liberty.

Superpowers need origin stories — nations no less than comic-book heroes. The Pilgrims are ours. Forget the fortune-hunters of Jamestown; the tale of doughty settlers seeking religious liberty and overcoming hardship to establish the self-governing Plymouth Colony is the origin story we want. As John Turner observes in his excellent new history of the colony, “by the early nineteenth century, the Pilgrims had become symbols of republicanism, democracy, and religious toleration.” The Pilgrims are part of our national pantheon and its narrative of America as a nation devoted to liberty.

Revisionist historians have assailed this mythos, arguing that the Pilgrims were not trying to beat a thoroughfare of freedom across the wilderness. Rather, they accepted slavery and refused to extend religious liberty to others. Despite the iconic day of thanksgiving providing a “heartwarming story of two peoples feasting together instead of fighting each other,” Pilgrim settlers often wronged the natives. Furthermore, Plymouth was soon overshadowed by the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. By this reckoning, the Pilgrims were historically negligible and morally unworthy of our admiration — their significance derives from our printing their legend rather than the facts.

Turner’s book, They Knew They Were Pilgrims, alternately affirms and challenges both the popular mythos and its critics. Beginning with the separatist movement in England and continuing until Plymouth was incorporated into Massachusetts in 1691, Turner provides an engaging account of the Pilgrims, from Calvinist theology to colonial politics. While validating some criticisms, he asserts that the Pilgrims matter for more than their legend, and he deftly uses the history of Plymouth to explore ideas of liberty in the American colonies.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NATIONAL REVIEW

How America’s First Banned Book Survived and Became an Anti-Authoritarian Icon

The Puritans outlawed Thomas Morton’s “New English Canaan” because it was critical of the society they were building in colonial New England.

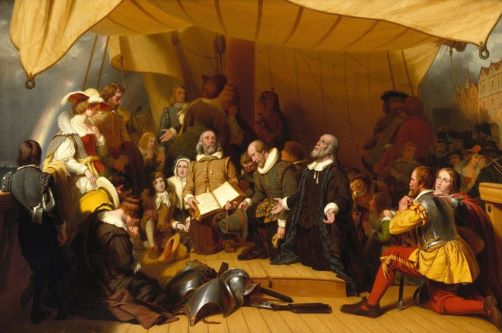

When the Puritans set sail for New England in 1630, they likened themselves to ancient Israelites settling in the promised land. Liberated from the Church of England, which they viewed as too Catholic, they sought to reform the church and establish a new Christian commonwealth guided by their covenant with God.

“We must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill,” John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, famously proclaimed on the journey over from England. “The eyes of all people are upon us, so that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken and so cause him to withdraw his present help from us, we shall be made a story and a byword through the world.”

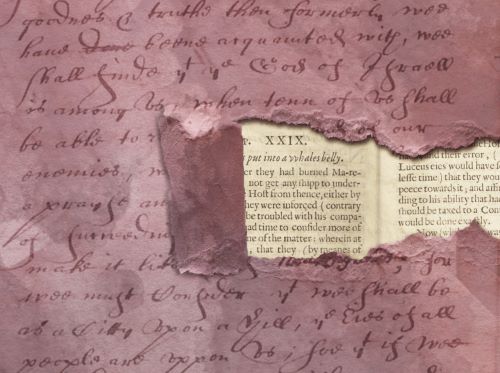

Just seven years after the Puritans’ arrival, an Anglican lawyer named Thomas Morton published a book that threatened the young colony and its residents’ covenant with God. New English Canaan, a three-part text published in Amsterdam in 1637, is mostly filled with detailed observations about the region’s Indigenous people and descriptions of plants, animals and natural resources that could be commodified by white settlers. But a brief section at the end offers a withering critique of the Puritans and the society they were building, including their treatment of Native Americans.

Members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—known to be a tightly controlled society—adhered to strict beliefs about how to live and worship. Women and children were taught to read so they could learn directly from the Bible, but few other books were imported. Public entertainment wasn’t allowed except for church services. Cursing was punishable by law. Despite harsh winters and conflicts with Native Americans, the Puritans believed their colony would survive if they obeyed God, and they were constantly on the lookout for signs from above.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE

Puritanism as a State of Mind

Whatever the “City on a Hill” is, the phrase was not discovered by Kennedy or Reagan.

Recent generations of Americans have become accustomed to hearing their country referred to as a “City on a Hill,” a phrase which usually means that it is, or can be, a moral exemplar. In a 1961 address to the General Court of Massachusetts, President Kennedy introduced contemporary political discourse to the phrase from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:14). Google’s Ngram Viewer demonstrates the proliferation of the phrase after President Reagan famously used it on the eve of his election in 1980 and then closed out his two-term presidency with it in 1989. President Barack Obama deployed the phrase, as have many other politicians in both major parties.

Our recent national self-examination, however, suggests that the top of the hill has become more of an ambition than an accomplishment. Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman’s dynamic “The Hill We Climb,” for example, read at the inauguration of President Biden, articulated America’s moral challenges and returned instead to a more aspirational verse in American political theology: Micah 4:4, the hope that everyone may someday “sit under their own vine and fig tree, and no one shall make them afraid.”

Whatever the “City on a Hill” is, the phrase was not discovered by Kennedy or Reagan, of course. They deployed this scripture not only for its own sake, but to recall its historical use in a sermon by John Winthrop. Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, supposedly delivered the sermon aboard the Arabella just before the Puritan arrival in 1630. The sermon, and its role in American politics, has been the subject of three revisionist studies. In 2012, Hillsdale historian Richard Gamble questioned America’s “redeemer myth” and cautioned against enthusiastic civil religion. In 2018, Princeton historian Daniel Rodgers likewise challenged the invention of “historical myth” and recounted Americans’ wrestling with existential questions of destiny and morality. Winthrop’s sermon, A Model of Christian Charity, gained interest not just because of its historicity, but as an occasion to ask questions about the nation itself.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LAW & LIBERTY

“City on a Hill” and the Making of an American Origin Story

A now-famous Puritan sermon was nothing special in its own day.

What is the origin of America?

Ask that question systematically to more than 2,000 people, and a wide variety of answers will arise. Most focus on the founding era of the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the American Revolution, and the Constitution. Others turn to the colonial days observing that “America” existed long before the nation began. Some dwell on the Native Americans—the first people on the soil of the Americas. Others focus more on the arrival of Europeans. Amerigo Vespucci gets mentioned. The coming of Columbus. Jamestown, Captain Smith, Pocahontas. So many possible answers, so many different times and places to begin. And always, in the midst of these responses, one answer rises among the rest: Pilgrim Landing, Plymouth Rock, and the Puritans.

The question of American origins, of course, has no real answer. People can argue for their choice, but such debates tell us more about how they view America today than how “America” actually began. In that sense, historical origin stories function primarily as present-day descriptions. Each answer defines what a person means by America. Beginning with Native Americans, for example, suggests a story of chronological priority untethered to modern political boundaries: “America” is all the territory from the Bering Strait to the bottom of Argentina, and it includes all the people who have ever lived and moved and had their being on these lands. It is a long story, a tale teeming with diversity. Rather than beginning something new, Europeans stumble onto well-established nations and civilizations, disrupting traditional patterns and forms of life, adding to the mix, changing and reshaping an “America” that existed long before them.

Answers that emphasize the Revolutionary era, meanwhile, define America much more narrowly. Such responses focus on one particular nation coming into being at one particular time. Even here, however, the distinctions can be quite telling. Does “America” start with a fundamental statement of principles (the Declaration of Independence), a bloody war (the American Revolution), or the eventual establishment of a mostly stable government (the Constitution)? No doubt, most people see these answers as related, but the specific responses embed much different accounts of what makes America America after all.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT RELIGION & POLITICS

Thank the Pilgrims for America’s Tradition of Separatism, Division, and Infighting

They were not the nation’s first settlers, but they were the most fractious.

December marks the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing at Plymouth, the moment habitually yet mistakenly thought of as the beginning of America. The conflation of New England’s history with that of the nation at large, encouraged by generations of Harvard-reared scholars, continues to warp Americans’ understanding of their past. By the time the Mayflower dropped anchor off Cape Cod, the Jamestown settlement in Virginia had survived (barely) for more than a decade, while Spanish settlements at Santa Fe, New Mexico, and St. Augustine, Florida, were far older.

In part, the importance of the Pilgrims has been exaggerated because of the peculiarly American values that they are said to have brought to the New World and spread through the colonies: rigid discipline, austere rejection of earthly pleasures, the fusing of religious impulses with political ideas. All of these indeed distinguished the Pilgrims from other groups of early trans-Atlantic migrants, though the old easy binary between profit-seeking Virginians and pious Yankees no longer commands much respect among scholars.

Yet it is another attribute of the Pilgrim influence that arguably holds even greater sway four centuries after their arrival. Understanding that influence starts with the history of their name. The Pilgrims weren’t called that in their day. Instead, they were known as “Separatists,” for their desire to break completely from the Church of England, rather than cleanse and reform it from within—the approach urged by the more moderate Puritans.

That separatist impulse to leave an established community in protest of its corruption, to choose the remedy of “exit” rather than “voice,” would set the pattern for countless American protest movements to come. The Pilgrims, by word and deed, established separation as an actionable precedent for any American group alienated from the status quo. From colonial times to the present—especially in the Revolution and the Civil War—that secessionist impulse would define American history, and sometimes threaten to overturn it entirely.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT ZÓCALO PUBLIC SQUARE

Lord of Misrule: Thomas Morton’s American Subversions

When we think of early New England, we picture stern-faced Puritans. But in the same decade that they arrived, Morton founded a very different kind of colony.

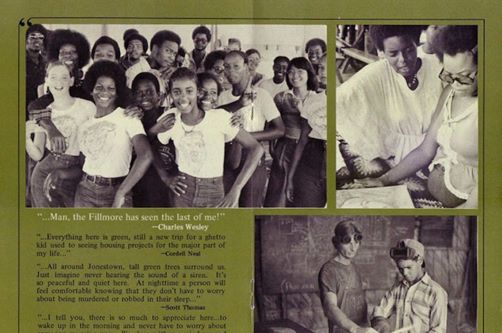

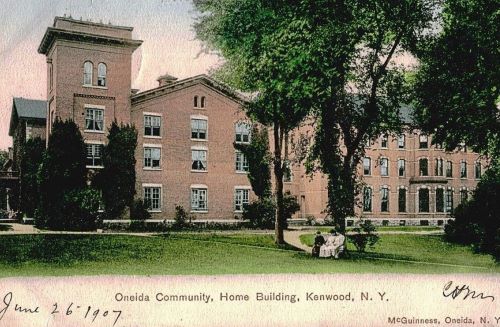

In 1620 the Mayflower shepherded in the founders of Plymouth Plantation, and in 1630 the Arbela brought John Winthrop with his sermons about the “city on a hill”, but during the decade that separates these canonical arrivals a very different sort of English colonist would establish a very different sort of colony on the South Shore of Massachusetts. Merrymount — founded as Mount Wollaston in 1624 near present-day Quincy, Massachusetts — was the brainchild of the Devonshire-born lawyer, raconteur, libertine, rake, and crypto-pagan Thomas Morton (1579–1647). His ideas for colonizing the New World were distinct from either the Plymouth or the Massachusetts Bay Colony. While generations of historians have claimed that Americans are intellectually the descendants of stern Calvinist Puritans and Pilgrims, Morton (who stood in opposition to both groups) had his own ideas. The utopian Merrymount, it has long been argued, was a society built upon privileging art and poetry over industriousness and labor, and pursued a policy of intercultural harmony rather than white supremacy. The site where it stood — now an industrial area across the road from a Dunkin’ Donuts — once bore witness to a strange and beautiful alternative dream of what America could have been.

Morton had first arrived in Massachusetts in 1622, only two years after the Mayflower had made its landing, but he returned to England after expressing dissatisfaction with Puritan governance. A year later he returned and helped to establish a colony with his associate Captain Richard Wollaston, a notorious pirate and distinctly un-Puritan figure who named the settlement after himself. Mount Wollaston would come to an end shortly after its founding, when Morton discovered to his horror that the titular leader of the colony was selling its settlers into Virginian slavery. As a result, at some point in 1626, he encouraged an uprising against Wollaston, and upon the captain’s exile Morton became the new leader, renaming the colony variously “Mount Ma-Re” or “Merrymount”, a play on the Latin for sea, the Mother of God, and an emotion not associated with the Puritans — joy.

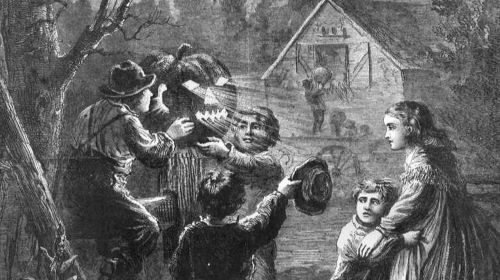

As Morton recounts, it was decided to mark, on May 1, 1627, this new naming of the colony with a party of “Revels and merriment after the old English custome”. For the occasion Morton set up a gigantic maypole, a “goodly pine tree of eighty feet long . . . with a pair of buck’s horns nailed on somewhat near unto the top of it, where it stood as a fair sea mark for directions on how to find the way”. Settlers and local Massachusett alike were encouraged to join in the revelry for which there was “brewed a barrell of excellent beare and provided a case of bottles, to be spent, with other good cheare, for all commers of that day.” Such mixing with Native Americans and drunken carousing around a maypole, with its pagan associations, was a direct affront to Morton’s Puritan neighbours. A repeat celebration the following year, after a further twelve months of Merrymount subverting Puritan norms, saw the Plymouth commander Myles Standish (a short man later slurred by Morton as “Captain Shrimp”) march a garrison into the idolatrous settlement, cut down the maypole, and have Morton sent off back to England in fetters.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE PUBLIC DOMAIN REVIEW

The Pilgrims’ Attack on a May Day Celebration Was a Dress Rehearsal for Removing Native Americans

The Puritans had little tolerance for those who didn’t conform to their vision of the world.

Ever since the ancient Romans decided to honor the agricultural goddess Flora with lewd spectacles in the Circus Maximus, the beginning of May has signaled the coming of spring, a time of revival after a long, dark winter.

In Europe, the holiday – usually celebrated on May 1 – became known as May Day. Though traditions varied by country and culture, celebrants often erected maypoles and decorated them with long colorful ribbons. Townspeople, while indulging in food and drink, would frolic for hours. These rituals continue today in parks and on college campuses across the U.S. and Europe.

Throughout history, millions have embraced the holiday – except for the Puritans of early modern England. Though we tend to lump them together, the term “Puritans” included different groups of religious dissenters. Among them were the Pilgrims, who eventually decided to migrate to North America to create new communities according to their religious vision.

It is tempting to attribute the Pilgrims’ hostility toward the holiday to the doom-and-gloom stereotype of the Puritans as humorless and overly pious – the same tendencies that led them to ban Christmas festivities. But their attack on a maypole in Plymouth Colony in 1628 reveals much about their approach toward those who didn’t conform to their vision for the world.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE CONVERSATION

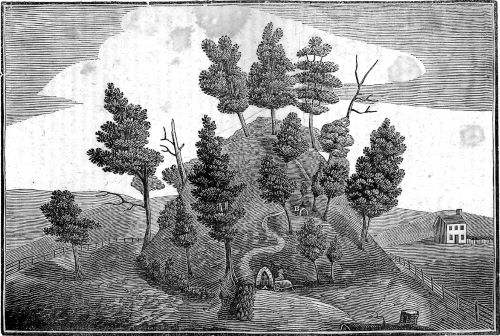

The “Indianized” Landscape of Massachusetts

In Massachusetts, the inclusion of Native American names and places in local geography has obscured the violence of political and territorial dispossession.

My wife and I, as relative newcomers to Massachusetts, decided to immerse ourselves more firmly in local history, and an internet search brought us to a website about Moswetuset Hummock. The next day, we drove to the South Boston shore, parked in a small lot, and walked up the hill. Heavily wooded, the hummock faces the Atlantic, backing into a tidal flat at the mouth of the Neponset River. It is not particularly tall, but despite ongoing efforts to drain the surrounding marsh, it dominates the landscape. Beside the trail stands a stone marker stating that this was the “home of the Moswetuset after whom the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is named.”

It is obvious that the state’s name is Native American, but I had never heard of Moswetuset Hummock or of the Moswetuset — now more properly known as the Massachuseuk. Not even my sons, who went to school here, knew of it or them. Yet the official seal of the Commonwealth features a sachem dressed in deerskin. This is an updated version of the first seal of Massachusetts Bay Colony, in use from 1629 to 1691, that showed a nude man with a bush covering his groin and a scroll extending from his mouth bearing the plea “Come over and help us” — adapting a message supposed to have been registered by St. Paul in a dream about the Macedonians, and highlighting, at least theoretically, the Puritans’ evangelizing mission. The figure looks more like a conventional 17th-century portrayal of a Caribbean than a Massachuseuk, indicative of limited knowledge on the part of the colony’s founders-to-be regarding the people they intended to convert. After all, the seal was designed in England, before the Puritans set sail. Though the figure was later “corrected” in terms of clothing, it remained a fiction that has served for centuries to represent the Commonwealth, with the sachem holding an arrow pointing down, indicating his acceptance of colonial morality and authority.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT PLACES JOURNAL

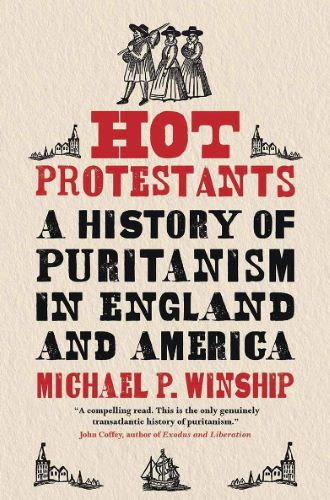

The Puritans Are Alright

A review of “Hot Protestants: A History of Puritanism in England and America.”

I do this penance for my naughty living and for fornication.

John Griffith, forced to publicly declare his sins in a Gloucester market, 1552

A puritan is such a one as loves God with all his soul, but hates his neighbor with all his heart.

John Manningham, 1602

H.L. Mencken, better known for his bon mots than the systemization of his thought, famously quipped that the essence of Puritanism was the “haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” Classic Mencken — funny, cutting, memorable. The sort of joke that has Mencken elevated into the pantheon of a Mark Twain or an Oscar Wilde, even if it takes a bit of flatulence to reach such an apotheosis. It’s also the sort of witticism that tells you something about the man who phrased it. The Puritans were a particular bugaboo for Mencken, as he (anachronistically) identified them as the ancestors of contemporary fundamentalists, and they were a convenient cipher for everything he found priggish, uninspired, prosaic, mundane, and tyrannical about American culture. As an aphorism, Mencken’s contention about Puritanism is easily quotable, and helps to establish he who is using those words as being on the journalist’s side of rationalism, of good humor, of joie de vivre.

Mencken prided himself on his rationalism, materialism, secularism, and atheism — the sort of man who, despite writing for a newspaper in a mid-sized Mid-Atlantic city, could still declare himself to be the “American Nietzsche.” This was a gentleman who was to have no time for the archaic faith, superstition, or bunkum that he thought defined American life; the stalwart critic of our simple-minded “boobocracy,” the reporter dutifully filing copy from the 1925 Scopes Trial in Dayton, Tennessee. “The way to deal with superstition is not to be polite to it,” wrote Mencken for the Baltimore Evening Sun, “but to tackle it with all arms, and so rout it, cripple it, and make it forever infamous and ridiculous.” Who wouldn’t prefer to have martinis at the Maryland Club with Mencken rather than praying in a back-numbing pew with Cotton Mather? And yet Mencken has always had his own tyrannical side — he was the racist, elitist, antisemite opponent of the New Deal who claimed that “[l]iberty and democracy are eternal enemies,” and who said of Benito Mussolini that “he is probably the most perfect specimen […] on view in the world today.” Suddenly, one wonders if they haven’t given Mather short shrift by comparison, at least in considering the source of our distaste.

Duplicitous to claim that, because Mencken was a nasty piece of work — bigoted, intolerant, and overrated — his great straw-enemy of Puritanism can somehow by exonerated. Certainly, it’s possible to hold these as two separate truths — that Mencken was a bit of a tyrant and that the Puritans were an unpleasant influence on the American mind, weighing us down psychically like an anchor dropped in Boston Harbor. Worth making us take a bit of an extra look though, for like Ambrose Bierce before him and Christopher Hitchens after, Mencken had the not unadmirable ability to simply assert something and through sheer power of rhetoric and humor make you ignore the fact that whatever was said is at best completely unsubstantiated and at worst totally incorrect. “The great artists of the world are never Puritans,” Mencken confidently wrote, as if he’d never heard of Daniel Defoe, Thomas Nashe, or Anne Bradstreet. Of John Milton. “No virtuous man […] [has written] a book worth reading,” he claimed, though Paradise Lost certainly seems worth it. Yet the Puritans remain our embarrassing grandfathers, they of buckled black shoe and wide-brimmed hat, remembered once a year as part of the saccharine civil ceremony of Thanksgiving and otherwise shunted away as our button-upped ancestors freezing in distant New England. For all that we’re dimly aware of these serious men, authors of the Mayflower Compact and “A Model of Christian Charity,” founders of Harvard and Yale, we can’t quite shake the feeling that they’re the sort of people who’d have brief, uncomfortable sex on a knotty wooden board. “Let us thank God for having given us such ancestors,” wrote Nathaniel Hawthorne, “and let each successive generation thank Him […] for being one step farther from them.” Seems about right.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

Why the Puritans Cracked Down on Celebrating Christmas

It was less about their asceticism and more about rejecting the world they had fled.

When winter cold settles in across the U.S., the alleged “War on Christmas” heats up.

In recent years, department store greeters and Starbucks cups have sparked furor by wishing customers “happy holidays.” This year, with state officials warning of holiday gatherings becoming superspreader events in the midst of a pandemic, opponents of some public health measures to limit the spread of the pandemic are already casting them as attacks on the Christian holiday.

But debates about celebrating Christmas go back to the 17th century. The Puritans, it turns out, were not too keen on the holiday. They first discouraged Yuletide festivities and later outright banned them.

At first glance, banning Christmas celebrations might seem like a natural extension of a stereotype of the Puritans as joyless and humorless that persists to this day.

But as a scholar who has written about the Puritans, I see their hostility toward holiday gaiety as less about their alleged asceticism and more about their desire to impose their will on the people of New England – Natives and immigrants alike.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE CONVERSATION

Read More Puritan Poetry

Coming to love Puritan poetry is an odd aesthetic journey. It’s the sort of thing you expect people partial to bowties and gin gimlets to get involved with.

“I am drawn, in pieties that seem/the weary drizzle of an unremembered dream.”

John Berryman, Homage to Mistress Bradstreet (1956)

At the height of their dominance, the North American mastodon traversed from the Arctic Circle to as far south as Costa Rica, going extinct during the Pleistocene about 11 millennia ago. With an average height of 14 feet and a weight of around eight tons, the pachyderm foraged throughout the frozen American forest for millions of years; white tusk glinting in moonlight, coarse brown hair hanging in ragged clumps from massive haunches, trumpeting trunk echoing in Yosemite, the Berkshires, the Adirondacks. Sometime in the last 20, or 30, or 40 thousand years, one of these mammoths perished in those virgin woods near what would be Claverack, N.Y., her body covered over in rich soil and her bones transmuted into fossils. Above her decaying corpse the glaciers would recede, then the ancestors of the Mahican would arrive, after them came the Dutch, and finally the English. A Knickerbocker whose name is lost to posterity was digging in a marsh by the Hudson in 1705 when he unearthed a five-pound honey-comb ribbed bright-enameled ivory molar. On July 23, the Boston News Letter printed report of a “great prodigious Tooth brought here, supposed by the shape of it to be one of the far great Teeth of a man.” Some of those who were enslaved, recalling their lives in Africa, remarked that the tooth looked similar to that of an elephant, but those observations were dismissed.

Edward Hyde, the infamous cross-dressing 3rd Earl of Clarendon and Governor of New York and New Jersey, had the molar dispatched to the Royal Society in London, with his own evaluation being that it was from some Antediluvian monstrosity, possibly the Nephilim spoken of in Genesis, the giant progeny of fallen angels and loose women. The Puritan divine Cotton Mather came to the same conclusion, citing the teeth in his Biblia Americana as evidence of the flood. And in Westfield, Mass., a minister named Edward Taylor wrote a poem about the gargantuan teeth. A private man, Taylor was taken to penning verse entirely for himself, and in the molar he saw a muse, writing 190 verses about how it evidenced the glory of God. “This Gyants bulk propounded to our Eyes/Reason lays down nigh t’seventy foot did rise/In height, whose body holding just proportion/Grew more than 7 yards round by Natures motion.” Taylor recorded his epic in a commonplace book of some 400 pages, which included lyrics that would eventually be regarded as the greatest of early American verse, described by Michael Schmidt in Lives of the Poets as a “strange voice, new and yet with old and tested tonalities,” sealed away in a leather-bound volume donated by his family to Yale’s Beinecke Library and fossilizing on some shelf until discovered in 1937, like an ivory tooth sifted from the silt.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE MILLIONS

Perry Miller and the Puritans: An Introduction

Historians often treat Miller as a foil, but the Father of American Intellectual history retains untapped potential to inspire new modes of inquiry.

Perry Miller was a complicated person. He was a teacher, writer, reader, literary scholar, O.S.S. officer, world-traveler, messy-eater, social critic, academic, alcoholic, atheist, spiritualist, philosopher, and, of course, historian. Was he the Father of American Intellectual history? I suppose there are a number of mid-century historians who might deserve that title, if it’s a valuable title at all, which is questionable. Regardless, Miller’s thought, if taken seriously and explored in all its delightful complexity, still retains untapped potential to inspire new modes of inquiry and writing in U.S. Intellectual history. Here is a brief (re)introduction to Miller as most of us first encountered him: historian of New England Puritanism.

By his own account, Perry Miller’s interest in the Puritans began when he was a student of literature at the University of Chicago in the late 1920s, after an accidental encounter and instant fascination with John Winthrop’s journal. Miller’s description of the incident resembles Hawthorne’s “discovery” of the scarlet letter in a custom-house, except that Miller’s fascination was with an idea rather than an object. But Miller found himself in an intellectual environment decidedly hostile to the study of ideas and even more hostile to the Puritans themselves. Progressive historians, most notably Charles Beard and Carl Becker, argued that material concerns, not ideological imperatives, were the motivating forces of history; ideology was merely a fig-leaf for these base motives. Furthermore, due to their unrelenting belief in progress, these historians viewed the Puritans– conservative even for the seventeenth century– as the enemy. Puritanism, social critic H. L. Mencken satirized, was “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, might be happy.” In this context, Perry Miller began his life-long argument that Puritan ideology should be taken seriously.

Perhaps in response to this hostile environment, perhaps because it was his nature, or perhaps not wanting to be out-done by H. L. Mencken, Miller’s writings contain sardonic denunciations of the value of the history of the material. “I am fully conscious that . . . I have treated in a somewhat cavalier fashion certain of the most cherished conventions of current historiography,” he wrote in the introduction to his first book, Orthodoxy in Massachusetts, published in 1933. “I lay myself open,” he continued sarcastically, “to the charge of being so very naïve as to believe that the way men think has some influence upon their actions, of not remembering that these ways of thinking have been officially decided by modern psychologists to be just so many rationalizations.” In 1961, in a new preface to The New England Mind: From Colony to Province, he again denounced the value of social history in the same cantankerous fashion, writing that after he once remarked ironically that the history of Puritan thought seemed to some historians “as much written by the actions of men of business as by theologians,” he was “soon appalled by the eagerness with which . . . reviewer[s] seized upon this . . . as a welcome release from the burden of ideas which my treatment had imposed upon them.” The most generous sentiment Miller could muster for the history of the material in this preface was his concession that “trade routes, currency, property, agriculture, town government and military tactics . . . indeed require an exercise of a faculty which in ordinary parlance may be called intelligence.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT SOCIETY FOR U.S. INTELLECTUAL HISTORY

Reading Puritans and the Bard

Without the bawdy world of Falstaff and Prince Hal and of Shakespeare’s jesters, there would have been nothing for those dissenting Puritans to dissent from.

History has a kind of conscious life in the institutions, ideologies, movements, and forces that seem to constitute the daylight workings of society; but it has a kind of nocturnal life as well—a dream world ruled by the various alchemies of metaphor and symbol, where the boundaries between one institution and another with which it is constantly at war, between an idea and its contrary, swim about in a kind of cultural ectoplasm where forms change places with one another, sending the spirit of one into the body of its sworn antagonist, bringing the dead back to life in new incarnations.

Robert Cantwell, When We Were Good: The Folk Revival (Cambridge, Mass., 1996)

Last year, over spring break, I attended the annual meeting of the Shakespeare Association of America (SAA), which happened to be held in Bermuda. For a historian accustomed to events like the AHA, OAH, or the Omohundro Institute’s annual conferences, let me tell you, SAA in Bermuda was an eye-opener. First of all, the Shakespeareans know how to party. Their receptions were lavish—one night, it was a buffet dinner with open bar in a swank Bermuda hotel, with a steel drum band and dancing. Why can’t we historians live like this?

But the conference was revealing in another way, or at least it confirmed a suspicion that had been growing on me for some time. As I listened with interest to the remarkable range of panels and papers devoted to Shakespeare and his world, it seemed ever clearer to me that Shakespeare is the major figure in the “nocturnal life,” the “dream world,” of early American history, if I may borrow Robert Cantwell’s compelling image. For a variety of somewhat surprising reasons, I have been exposed to more Shakespeare over the past dozen years than I might have anticipated. In addition to the Bermuda meeting, during which I forced myself to pay close attention to The Merchant of Venice in order to think about the problem of money in the Atlantic economy, I have also had the pleasure of watching my children, ages twelve and ten, appear in productions of The Tempest and Hamlet, and these experiences have fed a minor Shakespeare obsession on their part. Abetted by the theater opportunities of a smallish college town, they have attended at least a dozen full-scale productions of various Shakespeare plays—comedy, history, and tragedy—and seen versions of many others on video and DVD. For a historian of early America, especially one who has so far specialized in Puritan New England, all this Shakespeare has had a salutary effect.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT COMMON PLACE

This “Miserable African”: Race, Crime, and Disease in Colonial Boston

The murder that challenged Cotton Mather’s complex views about race, slavery, and Christianity.

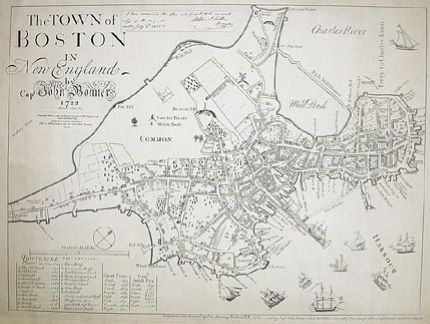

This is a story about how a small piece of historical evidence, just a few words on an old map, shed new light on a dramatic murder case from early-eighteenth-century Boston. The evidence involves the spread of a horrible disease that was a scourge of both the Old World and the New and that, recently, has returned to haunt our own. The legal case is that of Joseph Hanno, a freed slave from Africa who, in 1721, was executed for killing his wife. It was a crime of brutality, enacted on the margins of colonial society–and one that, ironically, would challenge the authority of one of the most important religious leaders of the day.

I had encountered the story of Joseph Hanno before. As a graduate student, I had read an essay titled “Narratives of Negro Crime in New England, 1675-1800.” The author described a sermon given upon Hanno’s execution as having “[set] the pattern” for the pamphlet accounts of black robbery, rape, and murder that peppered the colonies, stories that frequently implied that blacks were inherently inferior to whites–criminals by nature. As I debated how to begin a new book on the history of Afro-American citizenship, I recalled the article, and I soon found myself squinting at the first page of a sermon projected on the screen of a microcard reader. It bore an impressive title and an imposing array of typefaces (fig. 1): TREMENDA: The DREADFUL SOUND with which the WICKED are to be THUNDERSTRUCK, Delivered upon the Execution of a MISERABLE AFRICAN for a most inhumane and uncommon MURDER.

Who was this “miserable African”? From what evidence remains, we know that Hanno was a former slave, probably from Madagascar, who arrived in New England as a child around 1677. His masters were said to have “brought [him] up in the Christian Faith,” and Hanno, baptized and literate, came to be known in Boston for the breadth of his Christian knowledge: he once was described as “always vain gloriously Quoting of Sentences from [the Bible] wherever [he] came.” In 1721, about thirteen years after he was set free, Hanno was accused of murdering his wife, Nanny Negro, as she was getting ready for bed, by hitting her over the head with the blunt end of an axe. He was indicted, tried before a jury at the court of assize and general gaol delivery, convicted (after the trial, he admitted his guilt), and sentenced to die by hanging.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT COMMON PLACE

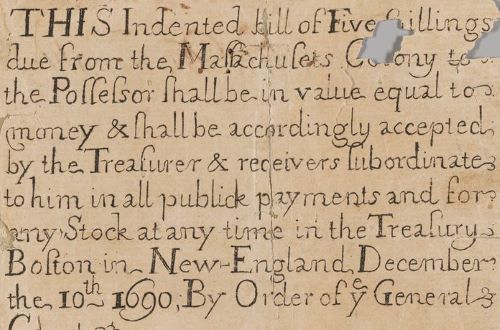

‘Easy Money’ Review: The Currency and the Commonwealth

Saddled with debt and forbidden by the crown to mint money, Boston’s Puritans dreamed up a novel monetary system that we still use today.

The year 1692 is infamous in Massachusetts history. It was then that, in Salem, hundreds of women—and men too—were accused of witchcraft, and 20 were tried and executed for an imaginary crime. In the same year, another momentous event took place in the colony, though it has nothing of the same notoriety: The Puritan leadership that had overseen the Salem Witch Trials—responding to some of the same social pressures that had fueled the witch craze—perfected a financial instrument that would prove to be the template for modern currency. In brief, they reimagined money primarily as legal tender for taxes, a conceptual revolution that makes the government’s authority the only source of a currency’s value. This is the basis of the monetary system that prevails throughout the world today under the reign of the Almighty Dollar.

Dror Goldberg’s “Easy Money” provides an engrossing narrative account of this lesser-known crucible. Although scholarship about the first American colonies could fill the Mayflower, Mr. Goldberg’s chronicle is the first book-length attempt to explain why a defining concept in our global financial system emerged within a desperate theocracy on the fringes of the British Empire.

Unlike Virginia and other early colonies in the New World, Massachusetts was led not by aristocratic adventurers but by the upwardly mobile middle classes of English society. And, as Mr. Goldberg points out, the colony was founded at precisely the moment when England was beginning the leap from an agricultural to a capitalist economy. Devout religious motives led the Puritans to Massachusetts, but financial ingenuity allowed their pious enterprise to survive and thrive.

Lacking the institutional structures that reinforced social order in the Old World, Massachusetts’s leaders relied on consensus and consent. Though the ministerial elite tolerated no dissent in its religious mission, on practical matters, such as raising revenue and spending it, the colonial government was the most democratically accountable in the world at the time. For good reason, Alexis de Tocqueville identified the colonial New England township as the seedbed of American democracy.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

How America Became “A City Upon a Hill”

The rise and fall of Perry Miller.

Perry Miller, a midcentury Harvard scholar of history and literature, was a giant of academe. From 1931 to 1963, as the scholar Michael Clark has summarized, Miller “presided over most literary and historical research into the early forms of American culture.” He helped establish the study of what he called “American Civilization,” contributing to the rise of a new discipline, American Studies.

Devoting himself to what he called “the meaning of America,” he tried to unravel its mystery and understand “America’s unending struggle to make herself intelligible.” After he died, the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr said that “Miller’s historical labors were . . . of such a high order that they not only gave delight to those who appreciated the brilliance of his imaginative and searching intellect, but also contributed to the self-understanding of the whole American Nation.”

That self-understanding, for Perry Miller, started with the Puritans. In graduate school, as Miller once recalled, “it seemed obvious that I had to commence with the Puritan migration.” The short prologue of his most widely read book, Errand into the Wilderness (1956), uses the words “begin,” “beginning,” “began,” “commence,” and “origin” fourteen times in three short pages, and almost all of those words applied directly to the Puritans. And because he began America with the Puritans—because he did so in such an original way and with such overwhelming force—he left in his wake a long train of scholars who took up the study of early New England with fresh interest, all of them re-envisioning Puritanism for the twentieth century.

Miller’s most lasting influence, however, came not from his overall study of the Puritans but from his assertions about one particular text. In deciding that “the uniqueness of the American experience” was fundamentally Puritan, Miller turned to the precise origin of America—the founding of Boston in 1630 with the arrival of John Winthrop on the Arbella. Or, to be more precise, he turned to the moment marked as an origin in a mostly forgotten text. After all, other Puritans founded Salem in 1628; the Mayflower Separatists established Plymouth in 1620; the Dutch arrived in Manhattan in 1609; the Spanish set up St. Augustine in 1565; and Native Americans had been here all along. Then, too, there was that other English colony farther south, Virginia, founded in 1607, which Miller dismissed for lacking the “coherence with which I could coherently begin.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES

What the Republican Debates Get Wrong About the Puritans

Pence invoked them at the Republican debates, but a true reckoning with their history provides a different vision of the nation’s future.

During the first Republican presidential primary debate, on August 23, former Vice President Mike Pence spoke of founders of the nation conquering the American “wilderness.” It was one of many mentions of American history: Candidates also name-checked the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the legacy of President Ronald Reagan. Toward the end of the evening, Pence stressed the wilderness theme: “If we renew our faith in one another and renew our faith in Him, who has ever guided this nation since we arrived on these wilderness shores, I know the best days for the greatest nation on earth are yet to come.”

Historical references are so ubiquitous in presidential debates and stump speeches that they can seem superficial. This year’s Republican candidates seem especially committed to the idea that the past matters, perhaps because of battles over history and ethnic studies curricula spreading in some states. If, as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis opined, “We cannot be graduating students that don’t have any foundation in what it means to be American,” then perhaps we also need to pay closer attention to what kind of American identity candidates are finding in history.

When Pence referenced conquering the wilderness, he used a keyword lifted from the Puritans. Those early American immigrants make cameos in plenty of political speeches, but often in ways that are misquoted or misunderstood, because their writings reflect a world of the 1600s, whose concerns are not identical to those of our time.

In England, the Puritans constituted a religious minority who opposed the state-sanctioned Church of England, which they believed had betrayed true faith. By leaving for North America, many believed they were testing whether their distinct vision of Protestant Christianity could survive in a new continent.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT ZÓCALO PUBLIC SQUARE

Great Awakenings

Darkness Falls on the Land of Light

Divisions in society and religion that still exist today resulted from the “Great Awakenings” of the 18th Century.

For my Part I can’t but think … That it is highly Incumbent on all who are not Seized with a Vertigo, to Stand upon their Guard, and in the most ardent Strains to lift up their Voice to the Most High, when the Religion of the Bible is like to be laid aside, for Some present immediate Inspirations—And not only so, but that Men should be often, and earnestly call’d upon and caution’d to Avoid that New Light which will lead Us into Darkness.

JOSIAH COTTON TO SAMUEL MATHER, 1742

Deep in thought, Hannah Corey stood alone among the gravestones of the Sturbridge, Massachusetts, burial ground, gazing across the common at the Congregational meetinghouse. She and her husband, John, had affiliated with the church in the west parish of Roxbury by owning the covenant shortly after their marriage in 1741. Two years later, they moved to the recently settled frontier of central New England and proceeded to join the Sturbridge church in full communion. They had presented each of their four children for baptism shortly after their births. Now, during the fall of 1748, Corey faced serious—even supernatural—misgivings about her place within the sole, tax-supported religious institution in town.

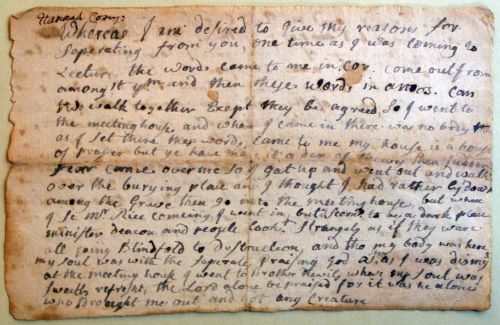

Corey had arrived early that afternoon for Caleb Rice’s weekday lecture. As she sat in the empty pews awaiting the Sturbridge minister and her neighbors, the words of Jesus’s stern rebuke to the moneychangers in Luke 19:46 suddenly darted into her mind: “My house is the house of prayer but ye have made it a den of thieves.” Corey had a strong intimation that this was no ordinary meditation, daydream, or idle musing. Instead, she interpreted the scriptural words as an oracular communication from the Holy Spirit. It was the third revelation she had received that day. Two other biblical passages had impressed themselves on her mind as she walked along the road to the meetinghouse. Amos 3:3 and 2 Corinthians 6:17 spoke directly to her reservations regarding the fitness of the Sturbridge church. “Can two walk together, Except they be agreed”? “Come out from amongst them.” The words thundered in her ears. Could she continue to walk with her neighbors in Christian fellowship? Was God commanding her to leave the church? With mounting concern, Corey confronted the troubling possibility that she had been worshipping for years in a den of thieves. “I thought,” she later recalled, “that I had rather ly down among the Graves than go into the meeting house.” So she fled to the adjacent burial ground to collect herself and contemplate the meaning of God’s powerfully intrusive messages!

Corey eventually quelled her fears and returned to her pew, but, as she listened to Rice’s sermon, she was overcome by a queer feeling. The entire meetinghouse “Seemed to be a dark place,” she remembered. The minister, deacons, and congregation “lookt Strangely as if they ware all going Blindfold to destruction.” Shaken by the peculiar turn of events, Corey and her husband abandoned their pew and retreated to the home of a neighbor named Isaac Newell. There, they gathered in prayer with a small group of disillusioned men and women who had just renounced their membership in the Sturbridge church. The dissenting faction included the town’s first deacon, Daniel Fisk, his outspoken brother Henry, and perhaps a dozen former church members and discontented parishioners from several neighboring towns.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT AMERICAN HERITAGE

The Person Formerly Known as Jemima Wilkinson

Awakening from illness, the newly risen patient announced that Jemima had died and that her body had been requisitioned by God for the salvation of humankind.

Mere months after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, a strange figure on horseback began to circulate throughout the New England colonies. The body atop the horse responded to the name of Public Universal Friend, and the double column of riders who followed behind their leader all believed that the Friend’s body housed the Spirit of God, sent to Earth to deliver an urgent message. Paying little heed to worldly skirmishes between Revolutionaries and Redcoats, the Friend galloped across the countryside announcing that the Apocalypse was drawing nigh. The Public Universal Friend exhorted audiences to heed heaven-sent warnings meant to save those who would listen, believe, and endeavor to live righteously — that is, according to the Friend’s advice.

God had selected a handsome female body for the Universal Friend to inhabit, one that had recently belonged to Jemima Wilkinson of Cumberland, Rhode Island. Jemima was known as an intelligent and attractive 23-year-old woman when she was struck by fever on October 5, 1776. Her family summoned a doctor when her condition worsened, but there was little to be done; the patient seemed doomed by the 10th, when her illness climaxed in babbling delirium.

Miraculously, the fever broke and the body calmed. According to family lore, Jemima’s body had chilled in death before it warmed and revived. The other Wilkinsons were astonished when her body arose from the bed on October 11. But if the family at first rejoiced that Jemima had been spared, they were mistaken: the newly risen patient announced that Jemima had died and that her body had been requisitioned by God for no less holy a purpose than the salvation of humankind.

Unusually, Jemima Wilkinson was unwed at the time of her illness: most of her peers were married mothers by their early 20s. She was born November 29, 1752, the eighth child of Jeremiah and Amey Whipple Wilkinson, and was named after one of Job’s daughters. Amey would go on to have four more children, the last of these deliveries killing her in 1764. Jemima was only about 12 years old when this occurred but would later understand that her mother had spent her entire adult life pregnant and nursing.

Jeremiah Wilkinson did not remarry, carrying on with the family by himself. Like any young woman of farmer’s stock, Jemima was expected to help with chores and raise her younger siblings. Formal education was out of the question; at the time, women bore much of the responsibility of instructing their children, their daughters in particular. Lacking a mother, and expected to labor in the home, Jemima turned to books, proving herself a prodigious autodidact. Aside from the Bible, she read deeply from the work of esteemed Quakers, including George Fox, William Penn, and the martyr Marmaduke Stephenson, one of three Quakers executed in Boston in 1659.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

God and Guns

Patrick Blanchfield tracks the long-standing entanglement of guns and religion in the United States.

“But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”– Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History

“The truth about the world, he said, is that anything is possible. Had you not seen it all from birth and thereby bled it of its strangeness, it would appear to you for what it is, a hat trick in a medicine show, a fevered dream, a trance bepopulate with chimeras having neither analogue nor precedent, an itinerant carnival, a migratory tentshow whose ultimate destination after many a pitch in many a mudded field is unspeakable and calamitous beyond reckoning.”- Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE REVEALER

The Unquiet Hymnbook in the Early United States

Exploring the ways that religious ideologies and communities shaped the revolutionary era.

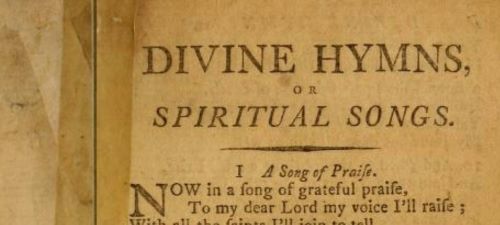

It’s not much to look at. Just over 13 centimeters tall, wrapped in a rough paper over scaleboard and a cheap leather spine (the paperback binding of early America), this book wasn’t even allowed to stay in the local historical society that glued shelf-marks to its cover. And yet Divine Hymns, or Spiritual Songs; For the Use of Religious Assemblies and Private Christians (New London, Conn., 1797) was an engine of social and cultural change, alongside tens of thousands of similar copies and hundreds of titles that flooded the Anglophone print market of the later eighteenth century. Those ubiquitous volumes were hymnbooks, words-only collections of a new kind of worship text that spent the eighteenth century migrating from a private devotional context to the heart of the Sunday church service. Only almanacs were produced in greater numbers; only Bibles were read more often. Yet we have been slow to recognize the historical role of these books that seemed to be everywhere, leaving them in the background of our understandings of religion, print, reading, and identity. As it turns out, many of our stories of reading, piety, and secularization (among others) can look quite different once hymnbooks are given their due.

Much of the hymnbook’s success in the latter half of the eighteenth century lies in a central tension in the genre: while the book’s various texts could fire the emotions, its paratexts—stanzas, numbering systems, indices—gave a collective sense of control, of system, and thus of rationality. In this sense, the hymnbook exerted its influence at the cutting edge of secularism in an age of both revival and reason. These books were unquiet, in the sense developed by Colin Jager, containing and distributing energies and emotions in their texts and the performances they afforded; these energies resisted control or explanation. As Jager argues, “a simple but crucial fact” often neglected in studies of early American and transatlantic religion is “that secularism is not first and foremost about religion but concerns instead power.” As religious change in the eighteenth century led to “new forms of social significance,” Jager writes, those forms readily appeared in “noisy” or “unquiet” ways, from large revival meetings to heightened individual affect. And few religious practices in early America were as noisy as hymn-singing.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT AGE OF REVOLUTIONS

A History of the Jerks: Bodily Exercises and the Great Revival

A digital archive of first-person accounts from the turn of the 19th century chronicling an unusual display of religious ecstasy.

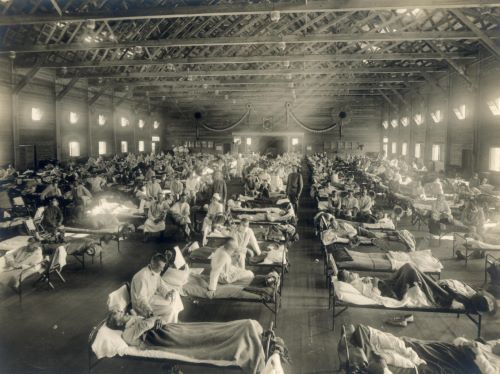

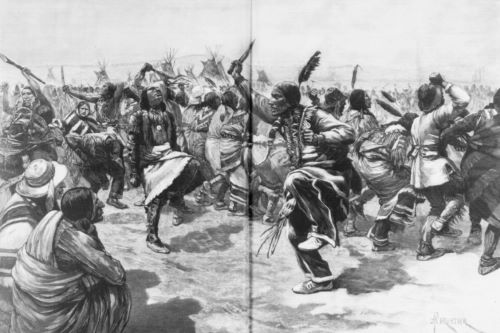

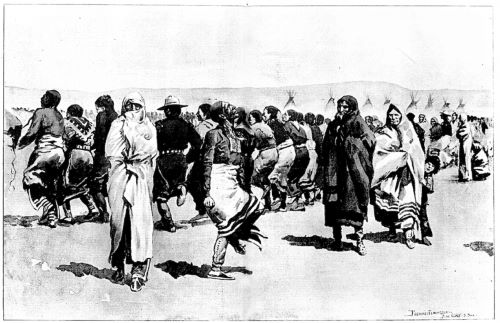

Between 1799 and 1805, the backcountry settlements of the early American frontier blazed with religious excitement. From western Pennsylvania to northern Georgia, middle Tennessee to the Carolina piedmont—but especially in the Bluegrass Country of Kentucky and southern Ohio—tens of thousands of frontier settlers gathered for multi-day, open-air religious meetings in which teams of Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian ministers preached from morning until late at night. Ministers claimed to have converted thousands at camp meetings during the first decade of the nineteenth century. From innovations in theology and hymnody to church organization and denominational proliferation, the Great Revival played a decisive role in the development of early American evangelicalism and the southern Bible Belt.

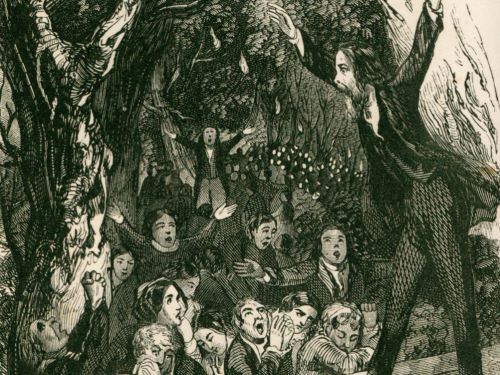

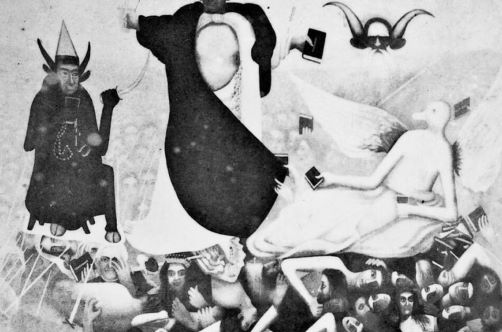

The revivals also stimulated the development of innovative new religious practices known collectively as the “bodily exercises.” Men and women in the throes of conversion collapsed to the ground, then rose up and began dancing. Others lay insensate for hours, enraptured with dramatic visions of heaven and hell. Camp meeting participants barked liked dogs, scampered up trees, engaged in trance walking, ran headlong through the woods, faced off in mock boxing matches, and burst into uncontrolled peals of holy laughter. Observers witnessed people speaking in unknown tongues and claimed to have heard music issuing miraculously from the chests of young converts.

Of the various somatic religious exercises that spread across the trans-Appalachian frontier and southern backcountry during the Great Revival, none drew more astonished commentary or more virulent opposition than “the jerks”: involuntary convulsions in which the subjects’ heads lashed violently backward and forward. More than half a century before the derisive phrase holy roller was coined to describe the ecstatic worship practices of Holiness and Pentecostal evangelicals in Appalachia, the subjects of these extraordinary bodily fits were known as “Jerkers.”

This Storymap sketches the controversial history of the so-called “jerking exercise” of the Great Revival and provides access to a curated digital archive of rare letters, diaries, journals, autobiographies, and published documents chronicling the history of the jerks over more than a century.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND

Paradise Lost

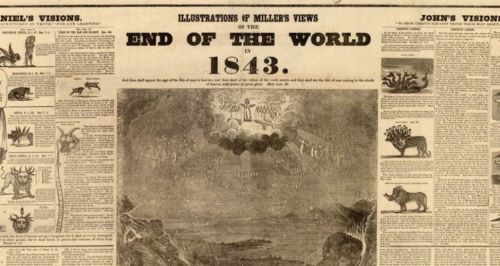

Why a hundred thousand Americans were ready to believe that Christ would return to earth in 1843.

BRIAN: This is BackStory with the American Backstory hosts. I’m Brian Balogh, 20th Century Guy.

ED: I’m Ed Ayers, 19th Century Guy.

PETER: And I’m Peter Onuf, 18th Century Guy. Our show today is all about the history of doomsday in America– prophecies and proclamations about what comes next, if anything.

ED: It’s hard to separate talk of the apocalypse from talk of religion. The very term apocalypse is most often associated with the New Testament book of Revelation. It means an uncovering or a revealing. Back in the 1830s and 1840s, America was experiencing a wave of religious fervor.

The Second Great Awakening, as it’s come to be known, was a time when many Americans thought the Second Coming of Christ was eminent. And so they threw themselves into reformed movements like temperance and abolition. They wanted to make America a fitting place for the coming kingdom of God, scrubbing out the sins of this world to pave the way for the next. It’s in this context that one particular end times prophecy caught fire and became remarkably mainstream. Jess Engebretson tells the story.

VOICE-OVER FOR WILLIAM MILLER: I’m fully convinced that sometime between March 21, 1843 and March 21, 1844 Christ will come and bring all His saints with him.

JESS ENGEBRETSON: This particular prophecy was the work of a small town Vermont farmer named William Miller. Miller had become convinced of Christ’s imminent return back in the 18 teens, after applying some complicated arithmetic to the book of Daniel. But he was a cautious man, and didn’t want to spread the extraordinary news until he was quite sure he’d gotten it right.

Separation of Church and State Has Always Been Good for Religion

The US Supreme Court’s most recent decisions undermine centuries of established secularism within American government.

During the autumn of 1831, as the United States was in the midst of fervent religious revivals known as the Second Great Awakening, the French intellectual Alexis de Tocqueville attended a service at a Quaker meeting house in Philadelphia. Tocqueville was initially confused by the experience, writing in his classic 1835 account Democracy in America how he was unsettled by the silent gathering of women and men in a plain church. He finally said to a worshiper next to him, “I wanted to attend a divine service, but you seem to have conducted me to an assembly of deaf-mutes.” He was then gently corrected by the Quaker, who answered: “Dost thou not see that each one of us is waiting for the Holy Spirit to illuminate him? Learn to moderate thy impatience in a holy place.” Benevolently chastised, Tocqueville sat alone with himself and the spirit, contemplating the man’s words, until there was an interruption. Another Quaker stood up and spoke of the “inexhaustible goodness of God and of the obligation of all men to help each other, whatever might be their beliefs or the color of their skin.” After the U.S. Supreme Court’s rulings these past two weeks, it would be helpful to revisit this history.

Of aristocratic stock and nominally Catholic, Tocqueville had never quite observed anything like this Quaker service. This denomination was periodically persecuted in Europe but had found a home in Pennsylvania since that colony’s founding in the 17th century. It had thrived alongside other non-conformist denominations since the new Republic had been founded as an officially disestablished state which recognized no official creed. Leo Damrosch writes in Tocqueville’s Discovery of America that “Philadelphia had every possible shade of belief on view. One visitor counted thirty-two churches representing seventeen different sects, as well as two synagogues.” This must have been dizzying to the Frenchman who came from the land—as his countrymen Voltaire had joked—of a thousand sauces and one religion.

This month, the Supreme Court released rulings for Carson v. Makin and Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, both 6-3 decisions which broke among the justices according to predictable ideological lines. In the first case, the court ruled that it was unconstitutional for the state of Maine to deny taxpayer funded educational vouchers for parents to pay for student tuition at schools with an explicitly sectarian curriculum. The second case ruled in favor of a Washington state football coach, employed by a public high school, who officially ended each game with a Protestant prayer and reprimanded students who refused to join. By setting this dangerous precedent, the Supreme Court threatens a truly distinguishing feature about American democracy. It breaches the wall of separation between church and state, betraying the ethos which so impressed Tocqueville.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT RELIGION & POLITICS

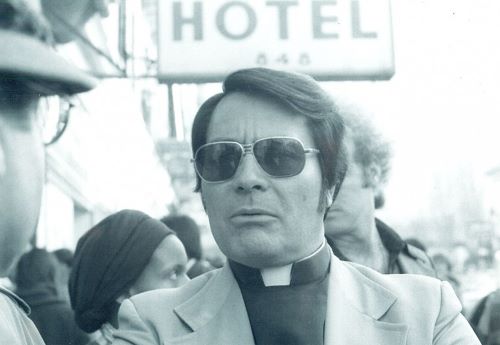

The Rise of Pentecostal Christianity

While the world’s fastest-growing religious faith offers material benefits and psychological uplift to many, it also pushes a reactionary political agenda.

Robinson

I do want to discuss the ways that your book documents how these churches are adapting to the 21st century through being very social media savvy. But first, let’s go back. Where did this come from? This distinct Holy Spirit-infused sub-branch of evangelical Christianity?

Hardy

So it’s generally attributed to what’s called the Azusa Street Revival, which happened in Los Angeles in 1906. And it was led by the son of freed slaves from Louisiana, a man named William J. Seymour. He’s credited as the founder of Pentecostalism, although I think his mentor, who was a white man, probably has a better claim. His name was Charles Fox Parham, an itinerant Methodist preacher from Kansas. And he was practicing a lot of stuff that was coming around in 19th-century America, with frontier culture and all sorts of things that happened after the Civil War—whether it was women starting to preach or people perhaps angry with organized religion or things just changing and that real kind of wandering, conquering spirit that I think was going on in America. Some strains of new thought, like Ralph Waldo Emerson.

So it really emerged out of Methodism. And that’s where Charles Fox Parham really got going. He had a dispute pretty early, because he wanted to practice some of these new bents on really taking on the Holy Spirit, and speaking in tongues, and getting those blessings bestowed upon you that people started to talk about. This stuff had really died out a couple of centuries after Jesus. Things like speaking in tongues were really confined to the monastery for millennia, and people started bringing some of these ideas back. So he and a group of followers in Kansas were really interested in healing; Parham and his young son were both quite sickly. If there isn’t great health care now, there certainly wasn’t back then. So a group got together in 1901, they were fasting and praying. And the Spirit came upon a woman called Agnes Ozman, and she started speaking in tongues. And I believe that at the time, they thought it was Chinese, and they were mocked in the press. They said that this wonderful moment had happened, and they were called the Tower of Babel and really ridiculed. But Parham was a pretty headstrong dude. And he began taking it around Kansas and Texas and Oklahoma and preaching this new bent on faith. And in Houston in 1906, he met his protégé, William J. Seymour. Because of Jim Crow laws at the time, Seymour had to take his instruction out in the corridor while the white men sat inside. But obviously, they were very, very different men in every way. But they had something in common and saw something in each other, and they used to go out preaching on street corners. Parham preached to the whites, and Seymour would preach to the Black people, and Seymour was then invited up to a church in Los Angeles and pretty soon locked out, which always seemed to happen to Pentecostals—someone would lock them out. He had this huge moment. He had a group of followers then and they were praying and fasting for days on end.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT CURRENT AFFAIRS

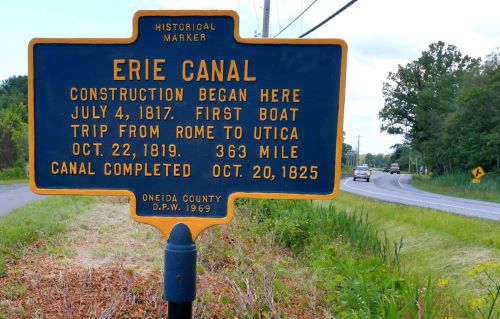

The ‘Psychic Highway’ that Carried the Puritans’ Social Crusade Westward

Elements of the Puritans’ unique worldview were handed down for generations and were carried westward by their descendants, the people we call Yankees.

It took me six days to drive the 700-odd miles from Boston, Massachusetts, to the grave of Charles Grandison Finney in Oberlin, Ohio. My last-minute trip wasn’t terribly well planned. I had allowed for some audible calls, serendipity, and unrelated detours. (Like an opportunity to tour the Lucille Ball Desi Arnaz Museum in Jamestown, New York. It was fabulous.)

My journey was part historical tourism and part pilgrimage. There’s nothing like being in a particular city or region to make history and its stories come to life, even if you are hundreds of years removed.

I’d long wondered how, in a nation that fetishizes size, tiny New England managed to inject so much of its culture into the American mainstream. I’d been reading about the Puritans for years, but at some point I realized that my interest was less in them and more about the legacy they left to America.

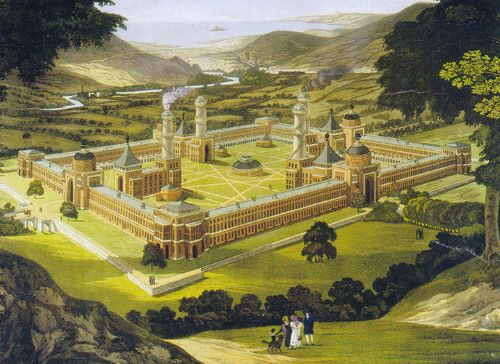

New England Puritanism, historians tell us, ran its course by the early 1700s. But elements of the Puritans’ unique worldview were handed down for generations and were carried westward by their descendants, the people we call Yankees. This culture was transmitted in a variety of ways, through the establishment of schools, universities, publications, lecture series, social and political causes, commercial enterprises, as well as in the founding of cities and towns throughout the United States.

Long confident in their superiority, New Englanders sought to impose their culture on the country at large. Their first major regional expansion ran through Western New York State onto the northeastern quadrant of Ohio known as the Western Reserve.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT CONTRA MUNDUM

Spiritualism

The Fox Sisters

The story of Kate and Margaret Fox, the small-town girls who triggered the 19th century movement known as Spiritualism.

Joanne Freeman: But first we’re going to begin in the 19th century when the idea that the living could commune with the dead turned into a full fledged American religion. It was known as spiritualism. And while there’s been plenty of debate about what to make of it, most people agree on when and where it started. In 1848 in a tiny town in upstate New York. I’m going to hand things over now to Nate Dimeo to tell us the story of the Fox sisters.

Nate: People said the house was haunted and that was even before the two girls started talking to the dead. Kate Fox was 11, her sister Margaret was 14 when they moved into a little house in a nothing village, 40 miles East of Rochester, New York. A little house that all their neighbors knew as the one where the traveling salesman had been invited in years before and was never heard from again. Never heard from that is until one night in March of 1848 when their parents first heard the sound. Some nights it would sound like knocking other nights like furniture moving and it always seemed to come from the girl’s bedroom. But they’d open the door and their daughters would be fast asleep.

Nate: They never suspected that their daughters could be tricking them. They were just young girls, but they were tricking them. What started with a little tap tapping on the wall and tiptoeing back into bed with giggles muffled by pillows, got more sophisticated as the nights went on. And on the night of March 31st the Fox sisters revealed the latest in their growing repertoire of ghost stimulating techniques. The one that would place the two girls at the center of a cultural and religious revolution.

Nate: They call their mother into the room. Margaret snapped her fingers once and they heard a tap and response. She snapped twice and it tapped twice the next night. All of their neighbors squeezed into the girls candle it room. They explained that one tap meant yes, two taps meant no. And then they started asking questions. And in the morning the audience left convinced that they had spent the night in the presence of a dead man and two girls with incredible powers.

Nate: Mr and Mrs. Fox wanted to protect their daughters and they sent them to live with their responsible older sister, Leah. But they soon found that the ghost followed the girls and Leah found an opportunity. She had booked her little sisters in a 400 seat theater in Rochester. By 1850 they were the toast of New York city. People would wait in line for hours to ask the sisters for words of their dead loved ones on the other side. William Cullen Bryant caught their act, James Fenimore Cooper, George Ripley, though we don’t know whether he believed it or not. The newspaper man, Horace Greeley introduced them to New York nightlife in the pages of his paper, introduced them to the world. Soon people were holding seances like we hold dinner parties, but even as spiritualism was sweeping the nation, it was leaving the sisters who started it behind.