The challenges of teaching in Trump’s America.

By Rann Miller

Educator and Freelance Writer

“Prism is an independent and nonprofit newsroom led by journalists of color. We report from the ground up and at the intersections of injustice.”

Teachers are under attack.

Not teachers who choose to be apolitical, but teachers who actively choose to teach the truth to children. The truth is that the U.S. has a history of sins that include genocide and enslavement, both of which have played a role in the country’s successes. The truth is that families in the U.S. are often defined by societal constructs designed to foster control, compliance, and complicity. In President Donald Trump’s America, educators are at great risk if they teach these truths. But the problem is that there’s no such thing as apolitical teaching in the classroom. Teaching is political, whether you force students to recite the pledge of allegiance or allow them to choose. It’s political if you teach the ugly truth about enslavement or skirt around it. It’s political even when you think it isn’t, such as reading only the literature of white men or deciding to incorporate the works of authors of color.

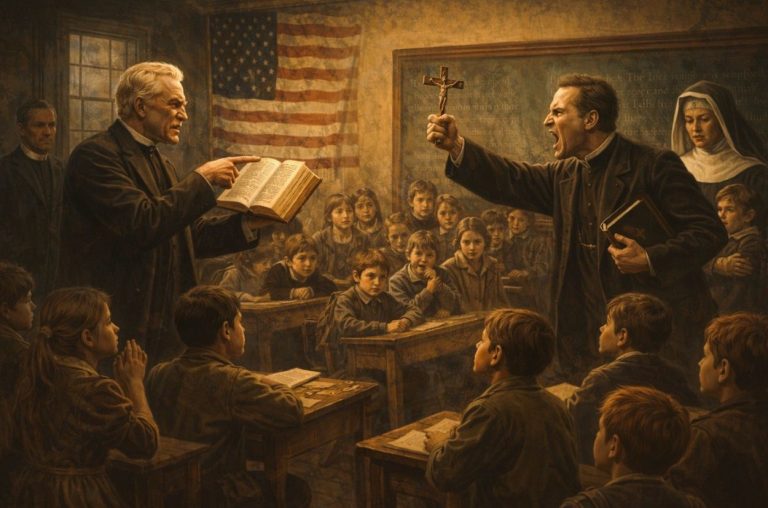

Truth can compel change because truth disrupts power. This is why conservative lawmakers have waged unprecedented attacks across K-12 education and universities: When educators teach the truth, lawmakers’ power is threatened.

The attacks from the Trump administration and states nationwide have been multifaceted, targeting critical race theory, Black history courses, and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives aimed at diversifying teachers, facilitating inclusive curricula, and creating equitable student outcomes. As a result, some educators are choosing to walk away from schools. Others have been forced out.

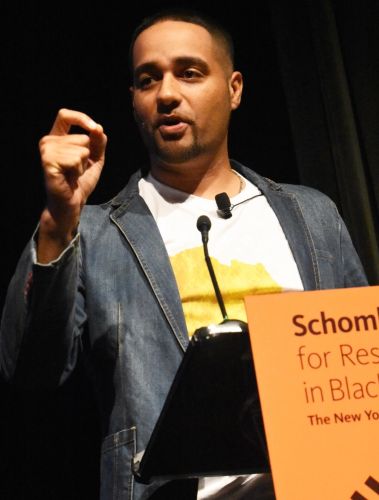

However, many educators remain in the fight. Jesse Hagopian has written a new book to help those teachers who are choosing to stick around. Hagopian is an activist and educator with more than 20 years of experience, 10 of which were spent teaching at a public high school in Seattle. His new book, “Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education,” was published by Haymarket Books earlier this year. Prism spoke to Hagopian about the roots of teacher censorship, his call for a defense of teaching truth, and ongoing attacks against Black education. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Rann Miller: What inspired you to write this book?

Jesse Hagopian: My supreme inspiration is my ancestors. When I stood at the [plantation] gravesite where my ancestors buried each other, I made a promise to them that I would never hide the true history of what they went through. The resistance of educators was a major inspiration for this book. I knew there were some incredible stories of teachers that I had worked with in the movement who risked everything to teach students the truth, and I had to tell their stories. They didn’t just curl up into a ball and accept this unjust punishment; they began raising their voices to fight for other teachers who were being attacked. As a lifelong educator, I knew I had to write something about this. When [legislators] started passing laws, trying to mandate that teachers lie to kids about Black history, about U.S. history, about systemic racism, about gender, about sexuality, I knew I had to speak out.

Miller: Why do you think it’s important for teachers to be aware that there’s a long history behind the attacks on education and educators that we’re seeing today?

Hagopian: If you want to teach students the truth, then you have to go beyond the textbook—you have to understand when the attack on Black education got started. In 1740, South Carolina passed the first anti-literacy law, a direct result of the Stono Rebellion in 1739. After the Civil War, Black people built the public school system in this country. In the North, there were public schools, but how public can we call them if they excluded Black children? This is the legacy of today’s uncritical race theorists. This is their tradition. Our tradition is the fugitive pedagogy Dr. Jarvis Givens writes about; that’s the tradition I want to raise today. Today’s teachers who are teaching the truth despite this white supremacist backlash to the 2020 uprising stand in that tradition. They need to know that history.

Miller: In your new book, you discuss the concept of “educational arson.” Can you explain what you mean by this?

Hagopian: The educational arsonist history that I talk about during the Reconstruction era when 600 Black schools were burned down, unfortunately, isn’t over. Throughout U.S. history, these arsonists—racists—have used the power of the flame and the explosion to attack Black education. During the civil rights movement, they bombed a school in Tennessee that was integrating. In the 1990s, a wave of Black churches, sites of education, and Sunday schools for Black children were set on fire. In 2022, there were bomb threats to HBCUs. We have politicians today threatening to burn books. This is the violence of “organized forgetting,” as Professor Henry Giroux calls it. That is the tradition of educational arson.

Miller: Talk to me about “epistemicide,” another concept you discuss in the book.

Hagopian: Epistemicide is the destruction of knowledge, ideas, and culture, which is part of genocide. When the Spanish bishop, Diego de Landa, came into contact with the Mayan people in 1562, he snatched every last one of their books and burned them all in a giant conflagration of ignorance. That is one of the great crimes against humanity and a most terrible example of epistemicide. We might not be burning books at the same rate as the Mayan conquistadors or the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction, but by banning them, the power structure is achieving a similar outcome. In Florida, you can be charged with a felony if you get caught with a banned book in your classroom on topics around race, gender, or sexuality. You can receive a felony, five years in jail, and a $5,000 fine. That is certainly an example of epistemicide.

Miller: Chapter two of your book touches on how the Red Scare and McCarthyism played a part in the fight for racial justice and, more broadly, how this time period impacted how Black history is taught. This echoes some of the scholarship of Dr. Charisse Burden-Stelly. What is the connection between the Red Scare and what is known as “the Black Scare”?

Hagopian: If we want to understand what’s happening right now with these [education] laws, we have to study the McCarthy era that led to the Red Scare/Black Scare and the Lavender Scare. The Red Scare allowed the power structure to label anybody who raised questions about inequality or systemic racism as communist and then put them on the so-called blacklists and fired them from their jobs. Thousands of educators nationwide were fired during the Red Scare, including over 400 in New York City alone. These were teachers who wanted their kids to think critically about U.S. history and racism. The Lavender Scare was a major part of this McCarthy era that’s often not included in the discussion. More federal employees were fired under suspicion of being homosexual than even under suspicion of being a communist. Today’s “Don’t Say Gay” laws echo the Lavender Scare. This is where the divisive, homophobic, racist playbook draws itself from.

Miller: What do you see as the biggest challenge and the biggest opportunity for teachers under the Trump administration?

Hagopian: The sobering reality is that even before Trump, almost half of all students in the U.S. already went to a school where their teacher was mandated to lie to them about systemic racism. Trump has vowed to expand the number of kids who will be lied to about U.S. history. He wants to defund schools that teach the truth about Black history and other topics. But there’s a reason they are so worried. It’s because young people built the 2020 uprising across the country. These were mass multiracial movements in every single state of the nation where some 20 million people of all racial backgrounds linked arms and demanded an end to systemic racism, along with implementing Black and ethnic studies courses and removing police from campuses. It terrified racists. We have truth, justice, and the majority of people on our side. We need to get educated, get organized, and begin building the type of social movements that it takes to win. There are many signs that people are ready to build another great uprising like we’ve seen in the past, and now it’s time to roll up our sleeves and get the work done.

Miller: What do you hope educators and movement leaders take away from your book?

Hagopian: They should know that “Teach Truth” is a manual for the history we need to learn from and implement in our struggles for educational freedom today. They’ll learn about some of the greatest fights throughout history to defend Black and BIPOC education—not just so they can feel edified, but so they can use those lessons to help us fight today. You can either accept and allow our country to move towards unabashed fascism, or you can learn the history of the Black freedom struggle and other movements for social justice and then implement those today. That’s the choice I put before the reader, and I hope they join this great movement.

Originally published by Prism, 03.31.2025, republished with permission.