The New Deal was aimed at tackling the three major goals of relief, recovery, and reform.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Presidency and Depression

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency, which began in 1933 and lasted until his death in 1945, was a defining period in American history, marked by profound social, economic, and political transformation. FDR inherited the presidency during one of the most devastating times in the nation’s history—the Great Depression. The Great Depression, which began with the stock market crash of 1929, led to widespread economic turmoil. By the time Roosevelt took office, nearly 25% of the American workforce was unemployed, and the economy had contracted dramatically. Banks were failing at an alarming rate, and industrial production had plummeted. The stock market crash and its aftermath led to a massive loss of public confidence in both the economy and the government’s ability to manage it. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies aimed to combat these crises, restore economic stability, and bring relief to suffering Americans.

The Great Depression exposed deep flaws in the economic system, and the Hoover administration’s response was widely seen as inadequate. President Herbert Hoover, who had been in office during the early years of the Depression, was unable to prevent the economic downturn or offer sufficient relief to those affected. Hoover’s belief in limited government intervention in the economy led him to resist direct federal assistance for individuals. His policies, including efforts to balance the federal budget and maintain the gold standard, were not effective in addressing the urgent needs of the American people. As a result, the Depression deepened, and Hoover became increasingly unpopular. Roosevelt, on the other hand, promised a more hands-on approach to solving the crisis. He ran for president in 1932 with a platform that emphasized government intervention to provide relief to the unemployed, stimulate economic recovery, and reform the financial system to prevent future crises.

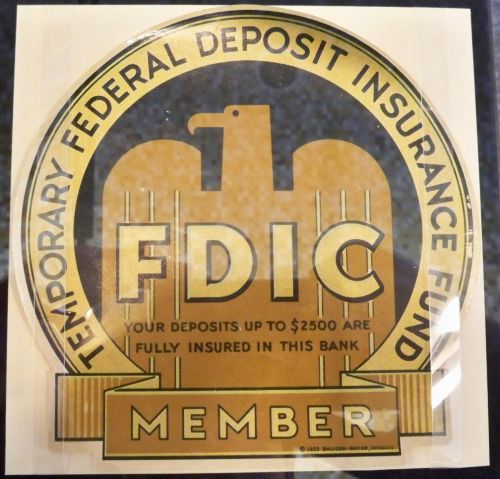

Upon taking office in March 1933, Roosevelt wasted no time in implementing sweeping reforms. He immediately called for the closure of all banks in the country in what became known as the “bank holiday” and began a series of bold legislative initiatives. In the first Hundred Days of his presidency, FDR pushed through a series of laws designed to provide immediate relief, reform the banking system, and foster economic recovery. These included the Emergency Banking Relief Act, which allowed banks to reopen under strict regulatory oversight, and the establishment of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which insured bank deposits to restore confidence in the financial system. Roosevelt also used the radio to speak directly to the American people through his famous “Fireside Chats,” in which he explained his policies and reassured the public during uncertain times.

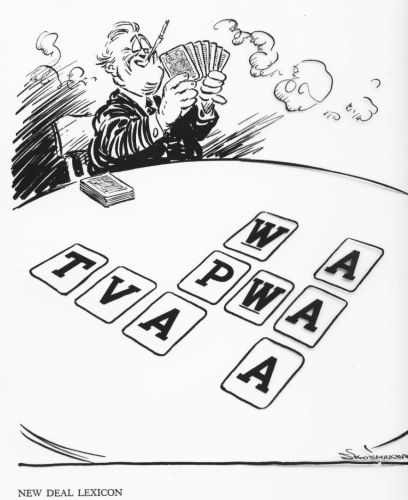

The New Deal, the series of programs Roosevelt implemented throughout his presidency, was aimed at tackling the three major goals of relief, recovery, and reform. The New Deal was not a single policy but a collection of programs and agencies designed to address different aspects of the national crisis. Among the most famous New Deal programs were the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which provided jobs for young men in conservation projects; the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which employed millions in public works projects; and the Social Security Act, which created a system of pensions for the elderly. FDR’s administration also reformed the financial system through the Securities Exchange Act, which regulated the stock market, and the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), which sought to raise crop prices by reducing agricultural production. These programs not only alleviated immediate suffering but also laid the foundation for long-term economic and social reforms in the United States.

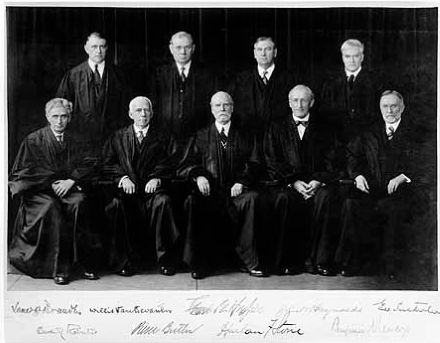

Despite its successes, the New Deal faced significant opposition from various political and economic factions. Critics from the left, such as Huey Long, argued that Roosevelt’s policies did not do enough to redistribute wealth and eradicate poverty. On the right, business leaders and conservatives feared that Roosevelt’s interventionist policies were eroding capitalism and individual freedoms. The Supreme Court, too, proved to be an obstacle, striking down several key New Deal programs, including the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Act. Roosevelt’s response was to propose the controversial Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, which sought to expand the Supreme Court by adding more justices. Though this plan failed, the challenges he faced ultimately led to a shift in the political landscape. Despite the controversy and opposition, FDR’s presidency reshaped the role of the federal government, marking a turning point in how the government interacted with the economy and its citizens. The long-lasting effects of Roosevelt’s leadership during the Great Depression continue to influence American policies and social programs today.

Need for Intervention

The necessity of federal intervention and reform to address the economic crisis during the Great Depression became increasingly apparent as the depth and duration of the downturn continued to wreak havoc on American society. By the time Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, the nation was in the midst of an unprecedented economic collapse. With one-quarter of the workforce unemployed, banks failing by the hundreds, and poverty spreading across urban and rural areas alike, the free-market system that had once been seen as the bedrock of American prosperity appeared to have failed. This dire situation left millions of Americans destitute, and traditional forms of private charity and state-level relief were unable to meet the scale of the crisis. As a result, there was a growing recognition that a large-scale, coordinated response from the federal government was necessary to restore economic stability, rebuild public confidence, and provide immediate relief to those suffering from the Depression’s effects.

Before FDR’s election, there had been some efforts to address the crisis, but these were seen as ineffective and insufficient. Under President Herbert Hoover, the government initially took a hands-off approach, relying on voluntary cooperation from businesses and state governments to stabilize the economy. Hoover believed that the federal government should not directly intervene in the market, adhering to a limited government philosophy that prioritized balancing the federal budget and reducing public debt. However, as the Depression deepened, these measures failed to curb the rising unemployment and widespread poverty. In contrast, Roosevelt’s platform in the 1932 presidential election emphasized the need for the federal government to take a more active role in directly aiding the American people. Roosevelt recognized that the economic crisis was not simply a temporary downturn but a fundamental breakdown of the financial system that required bold, innovative government action.

The urgency of federal intervention was highlighted by the collapse of the banking system, which crippled the economy and led to a massive loss of public trust. With more than 9,000 banks closing between 1930 and 1933, millions of Americans lost their savings, and the remaining banks were hesitant to lend money, further stalling recovery. Roosevelt’s response to this crisis was swift and decisive. Upon taking office, he declared a nationwide “bank holiday” to close banks temporarily and prevent further runs on them. He then passed the Emergency Banking Relief Act, which allowed only financially sound banks to reopen and instituted federal oversight to restore public confidence in the banking system. This was a clear demonstration of the necessity of federal intervention to stabilize key sectors of the economy and prevent further collapse.

Beyond banking reform, Roosevelt understood that the broader economic system needed to be reshaped to ensure long-term stability and prevent future depressions. The federal government’s intervention in various sectors was designed to address both the immediate needs of the public and the structural issues that had contributed to the economic crisis. One of the central aspects of Roosevelt’s New Deal was its emphasis on creating jobs and providing relief to those who had been left unemployed and impoverished by the Depression. Through agencies such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the federal government provided millions of Americans with employment opportunities in public works projects, infrastructure development, and conservation efforts. These programs not only provided immediate financial relief but also contributed to the long-term development of national infrastructure and the conservation of natural resources, thus aiding economic recovery.

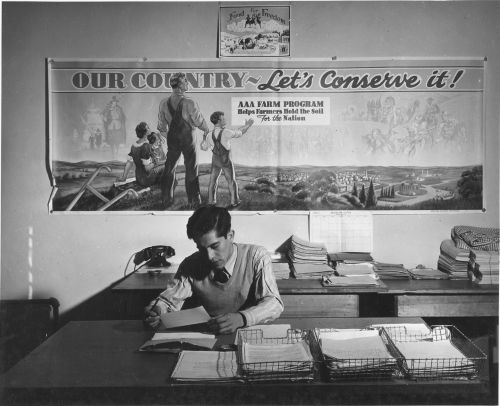

The need for federal reform also extended to the agricultural sector, which had been hit particularly hard by the Depression. Falling crop prices, combined with the effects of a severe drought, led to widespread hardship for farmers. Roosevelt recognized that without intervention, the agricultural sector would continue to spiral into further decline, exacerbating the economic crisis. The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was one of the first significant pieces of legislation aimed at addressing this issue. It sought to stabilize farm prices by reducing production and offering subsidies to farmers who agreed to cut back on their crops and livestock. While the AAA faced criticism and legal challenges, it highlighted the necessity of federal action in regulating and stabilizing agricultural markets. Through the New Deal, FDR laid the groundwork for a more balanced, regulated economy—one in which the federal government played an essential role in ensuring that all sectors of society, from industry to agriculture, had the support they needed to recover and thrive. This reimagining of the relationship between government and the economy marked a transformative shift in American governance, one that would have lasting effects on future policy and the role of the federal government in citizens’ lives.

The ‘New Deal’

The New Deal was a sweeping series of federal programs, reforms, and regulations introduced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during his first term in office, from 1933 to 1937. Aimed primarily at addressing the immediate effects of the Great Depression, the New Deal sought to provide relief to millions of unemployed Americans, stimulate economic recovery, and reform the financial system to prevent future crises. The Great Depression, which had begun with the stock market crash of 1929, left the United States in a state of economic devastation, with unemployment soaring to nearly 25%, widespread poverty, and a collapse of the banking system. The New Deal, as FDR’s response to this unprecedented crisis, represented a shift in the role of the federal government from one of relative hands-off non-interventionism to an active player in the economic and social life of the nation. Its guiding principle was that government intervention was essential to restore order, instill confidence, and provide both short-term relief and long-term economic stability.

The objectives of the New Deal can be broadly categorized into three main pillars: relief, recovery, and reform. The first goal, relief, focused on providing immediate assistance to the millions of Americans who were suffering from the ravages of the Depression. This included direct aid to the unemployed, the elderly, and other vulnerable populations. Federal programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) were designed to offer employment through public works projects. These projects not only provided jobs but also created much-needed infrastructure and revitalized neglected areas. Another aspect of relief was the establishment of Social Security, which provided a safety net for retirees and the disabled, a long-term reform that still exists today. Recovery was the second major goal, which involved restarting the economy and putting it on a path toward growth. Roosevelt’s programs aimed to stimulate industrial production, revive agricultural markets, and restore public confidence in the banking system.

The New Deal also sought to implement significant reforms to address the root causes of the Depression and ensure that such an economic catastrophe would not happen again in the future. One of the key reforms was the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which insured bank deposits to restore confidence in the banking system and prevent bank runs. Roosevelt’s administration also passed the Securities Exchange Act, which regulated the stock market and established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to monitor and control financial practices. Additionally, the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was designed to regulate industries, set fair wages, and improve labor standards. These reforms aimed to promote a more stable and equitable economic system, with a focus on creating a safety net for Americans in times of crisis and preventing the excesses of unchecked capitalism.

Another central objective of the New Deal was to tackle the severe disparities in wealth and opportunity that had become evident during the Depression. Roosevelt was keenly aware that the economic crisis had disproportionately affected the poor, farmers, and minorities. While many of his programs were aimed at providing relief to all Americans, others were specifically designed to support these vulnerable populations. The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), for example, was intended to reduce overproduction in agriculture by paying farmers to limit crop production, which helped stabilize prices and raise farm income. While not without its criticisms, the AAA sought to alleviate the suffering of farmers, many of whom had been driven into poverty by falling commodity prices. Roosevelt’s commitment to social justice and greater economic equality was also reflected in his support for labor rights, such as the right to unionize, which was advanced through the Wagner Act of 1935.

Despite the far-reaching impact of the New Deal, it faced significant opposition from both political conservatives and progressives. Some conservatives saw Roosevelt’s policies as an overreach of federal power, fearing they would lead to socialism and undermine American capitalism. Others, particularly business leaders, opposed the regulations and reforms that sought to curb the power of corporations and restore fairness to the marketplace. On the other hand, progressives and some left-wing critics argued that Roosevelt’s measures did not go far enough in addressing the systemic inequality in American society and the concentration of wealth and power among the elite. Nevertheless, the New Deal had a profound and lasting impact on American society and government. Its programs reshaped the relationship between the federal government and the American people, establishing a precedent for government involvement in economic and social welfare that continues to this day. While not all of Roosevelt’s initiatives succeeded or endured, the New Deal undeniably transformed the United States into a more interventionist, welfare-oriented state, setting the stage for future social and economic policies.

The New Deal: Context and Vision

Collapse and Action

The economic collapse of the Great Depression marked one of the most catastrophic periods in American history, with profound consequences that reverberated across the globe. The stock market crash of 1929, often seen as the trigger for the Depression, precipitated an unraveling of the economic system that led to widespread unemployment, poverty, and despair. In the immediate aftermath, stock prices plummeted, causing massive losses in wealth for both investors and average Americans who had invested in the market. The crash led to a loss of confidence in financial institutions, and this lack of trust snowballed into the closure of thousands of banks. As banks failed, millions of people lost their life savings, and credit became scarce, stalling consumer spending and investment. By the early 1930s, the national economy was in freefall, with unemployment reaching as high as 25%, leaving a quarter of the workforce without jobs. The collapse of industry and agriculture further deepened the crisis, with factories shutting down and farmers struggling with plummeting crop prices and mounting debt.

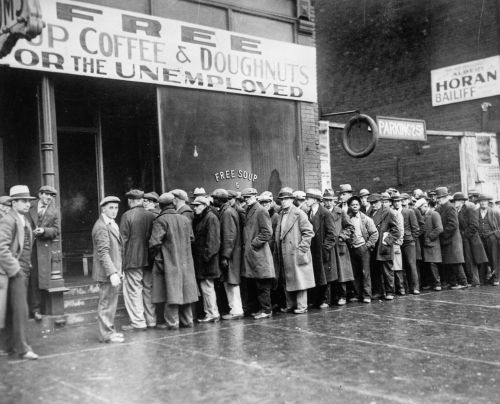

The immediate need for action became apparent as the economic catastrophe deepened. The scale of the economic downturn overwhelmed both local and state governments, which lacked the resources and infrastructure to provide the necessary relief to the millions of Americans now living in abject poverty. Private charities and volunteer efforts were unable to address the widespread suffering, and unemployment relief programs were insufficient to cope with the scale of need. In the face of mass unemployment, hunger, and homelessness, Americans became increasingly desperate, with many facing the loss of their homes and livelihoods. Homeless encampments known as “Hoovervilles” (named derisively after President Herbert Hoover) sprang up in major cities across the country, symbolizing the failure of the government to provide adequate assistance. The dire economic situation called for an unprecedented level of government intervention to stabilize the economy and offer direct relief to those most affected by the collapse.

In addition to the social devastation, the economic collapse led to a breakdown in the functioning of the financial system itself. Banks, which were the backbone of the nation’s economy, were collapsing at a rate never seen before. In 1933 alone, over 4,000 banks failed, leading to a severe loss of confidence in the nation’s financial institutions. Many Americans withdrew their money from banks, fearing they would never recover their deposits, creating even greater instability. The loss of faith in the banking system also resulted in a contraction of credit, which, in turn, stifled investment, consumer spending, and economic recovery. Businesses, unable to secure loans, reduced production or closed altogether, leading to even higher unemployment. The failure of the banking system exposed the vulnerability of the country’s economic structure and demonstrated the need for systemic reform. Without immediate action to stabilize the financial system, the economy could not recover, and further chaos was likely.

The agriculture sector, which had been struggling even before the Great Depression due to overproduction and falling crop prices, faced additional hardships as the Depression worsened. Farmers who had once thrived were now burdened with crippling debt, low commodity prices, and a devastating drought that struck the Midwest in the early 1930s, leading to the Dust Bowl. Many farmers were unable to pay their mortgages, and they were often forced to abandon their land, migrating westward in search of work and better conditions. Rural America, which was already struggling with the mechanization of agriculture and overproduction, found itself in dire circumstances. The crisis in agriculture exacerbated the overall economic collapse, contributing to the mass migration of families and creating additional social and economic pressures on already struggling urban areas. The collapse of agriculture highlighted the need for federal action to stabilize prices, assist struggling farmers, and implement long-term reforms to prevent future agricultural crises.

In light of the scale of the economic devastation, the immediate need for federal intervention was unmistakable. The existing government apparatus, under President Hoover, had been largely ineffective in addressing the depth of the crisis. Hoover’s belief in limited government intervention and his emphasis on voluntary cooperation from businesses and states failed to alleviate the widespread suffering. His attempts at public works programs and tariffs to protect American businesses did little to counter the massive unemployment and social dislocation. By 1932, many Americans were calling for more direct and substantial action, demanding that the federal government step in to provide relief and address the systemic failures of the economy. The 1932 election, in which Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated Hoover in a landslide, reflected a public desire for change and action. Roosevelt’s promise of a “New Deal” signaled that he was ready to break from the previous administration’s policies and provide a bold, government-led response to the economic crisis. The need for immediate action was clear: without intervention, the nation faced prolonged economic suffering, social unrest, and the potential for deeper instability.

Relief, Recovery, Reform

The goals of the New Deal were broad and multifaceted, aiming to address the immediate and long-term challenges of the Great Depression. These objectives were encapsulated in three key areas: relief, recovery, and reform. The goal of relief was to provide immediate assistance to the millions of Americans who were suffering from unemployment, hunger, and homelessness as a result of the economic collapse. With a quarter of the workforce unemployed and many families struggling to survive, Roosevelt understood that action was needed quickly to alleviate the immediate suffering of the American people. His administration passed a series of programs designed to provide direct aid to the unemployed, the elderly, and those unable to support themselves. Programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed millions of Americans in public works projects, offering both income and dignity through work. Additionally, the Social Security Act, which was introduced in 1935, was a landmark piece of legislation that established a federal pension system for the elderly and provided unemployment insurance for those out of work. These relief programs were crucial in offering a safety net for millions of Americans who were on the brink of collapse.

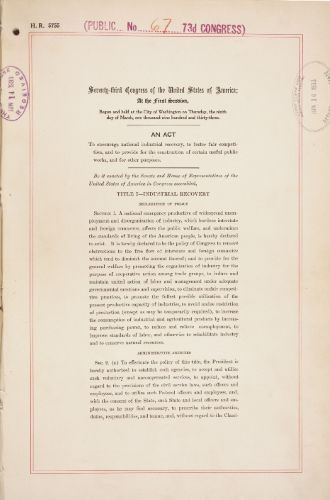

The second major goal of the New Deal was recovery, which aimed to restore the nation’s economy to a state of growth and stability. Recovery focused on restarting industrial production, reviving agriculture, and restoring consumer confidence. Roosevelt’s administration recognized that for the economy to recover, the federal government needed to stimulate demand, encourage investment, and provide incentives for businesses to hire workers again. One of the most significant recovery measures was the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), which sought to regulate industrial prices, wages, and working conditions. This act created the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which worked with businesses to set fair wages and prices, and promoted collective bargaining between workers and employers. Additionally, the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) aimed to restore agricultural prices by reducing crop production to create scarcity and drive up prices, offering farmers subsidies in exchange for limiting their output. These recovery programs were designed to stimulate economic activity, boost industrial and agricultural productivity, and create the conditions necessary for a sustainable recovery.

Alongside relief and recovery, reform was a key aspect of Roosevelt’s vision for the New Deal. While relief and recovery focused on addressing the immediate symptoms of the Depression, reform sought to address the root causes of the economic crisis and prevent future depressions. Roosevelt’s reforms were aimed at restructuring the economy and regulating financial markets to ensure greater stability and fairness. One of the most important reforms was the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in 1933, which insured bank deposits and restored public confidence in the banking system. By guaranteeing deposits, the FDIC reduced the risk of bank runs and made it less likely that ordinary Americans would lose their savings in the event of a bank failure. The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the establishment of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) were also critical to reforming financial markets. These measures sought to curb the speculative practices that had contributed to the stock market crash of 1929 and established federal oversight of the stock exchange to ensure fairer trading practices and protect investors from fraud.

Another key reform element of the New Deal was the focus on labor rights and the establishment of a more equitable economic system. The National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) of 1935 guaranteed workers the right to unionize and engage in collective bargaining, which had previously been restricted or discouraged in many sectors. This reform empowered workers to negotiate for better wages, benefits, and working conditions, leading to a dramatic increase in union membership and labor rights. Roosevelt’s reforms also extended to social welfare, with the creation of the Social Security Act, which established a federal pension system and unemployment insurance. The reform of the American economic system through these policies helped to reduce the extreme inequality that had contributed to the financial instability of the 1920s and created a more balanced distribution of wealth and power within society.

The New Deal’s three-pronged approach—relief, recovery, and reform—was not without its critics, but it undeniably reshaped the American economic landscape. Relief measures offered immediate assistance to those most in need, recovery efforts began to restore the national economy, and reforms sought to create long-lasting changes to prevent future economic crises. The New Deal laid the foundation for a more active role for the federal government in the lives of American citizens, from regulating markets to providing social safety nets. While not all of the New Deal’s programs succeeded or endured, its central principles of government intervention in times of crisis, protection of vulnerable populations, and regulation of economic practices have had a lasting impact on the U.S. political and economic systems. The New Deal was a response to an unprecedented crisis, and its goals of relief, recovery, and reform marked a turning point in the relationship between the government and the American people, changing the nature of the federal government’s role in shaping the nation’s economy and society.

Agencies and Goals

The role of government in economic planning and welfare during the New Deal represented a profound shift in the relationship between the federal government and American society. Prior to the Depression, the United States operated largely under a philosophy of limited government intervention in economic affairs. The idea that markets should be left to their own devices, with minimal oversight, was deeply embedded in American political thought. However, as the nation descended into the Great Depression, it became increasingly clear that such a hands-off approach had failed to prevent the collapse of the banking system, the loss of millions of jobs, and the widespread poverty that accompanied the economic crisis. In response, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration embraced a new role for government, one that included active intervention in the economy, the regulation of industries, and the provision of a social safety net for the most vulnerable members of society. The New Deal represented a new era in which the federal government took on a central role in planning and managing the economy to ensure stability and to promote the welfare of all citizens.

One of the most significant changes during the New Deal was the creation of new federal agencies that were tasked with overseeing and regulating various aspects of the economy. These agencies were designed not only to provide immediate relief to those suffering from the Depression but also to introduce long-term reforms that would stabilize the economy and prevent future economic collapses. The establishment of agencies like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Public Works Administration (PWA), and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) marked a departure from previous federal policies. These agencies were responsible for creating jobs through large-scale infrastructure projects, which included building roads, bridges, and public buildings. The government’s direct involvement in the creation of jobs represented a significant shift in economic planning, as it was no longer left to the private sector to solve the nation’s unemployment crisis. These agencies were a key component of the relief and recovery efforts of the New Deal, employing millions of Americans and directly addressing the immediate suffering caused by the Depression.

Beyond immediate relief, the New Deal saw the establishment of regulatory agencies designed to oversee and manage the economy in a way that would ensure long-term stability. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), created by the Banking Act of 1933, was one of the most important of these new agencies. Its role was to insure bank deposits, which helped restore confidence in the banking system after thousands of banks had failed during the early years of the Depression. By guaranteeing deposits, the FDIC effectively reduced the risk of bank runs, which had contributed to the economic instability of the early 1930s. Similarly, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was established in 1934 to regulate the stock market and protect investors from fraudulent practices. The SEC had the authority to oversee the trading of stocks and bonds, ensuring transparency and fairness in the financial markets. These agencies marked a major shift in economic governance, as the federal government took on a more active role in regulating industries and protecting the public from the excesses that had contributed to the crash of 1929.

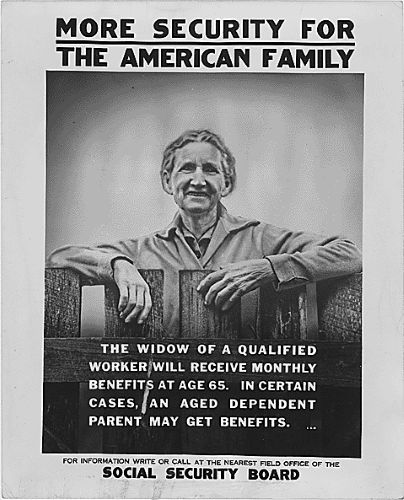

The government also became directly involved in welfare and social services through the establishment of agencies that provided direct aid to individuals. The Social Security Administration (SSA), created by the Social Security Act of 1935, was one of the most transformative of these new agencies. The SSA established a system of social insurance that provided pensions for the elderly, unemployment insurance for workers who lost their jobs, and assistance to the disabled. This represented a significant expansion of the federal government’s role in providing welfare and economic security for Americans. The creation of the SSA set the stage for the modern welfare state in the United States, as it was one of the first programs to provide a safety net for citizens in need. By guaranteeing financial support for the elderly, the unemployed, and the disabled, the SSA helped to address the economic vulnerability that millions of Americans faced during the Depression and in the years that followed.

The establishment of these new agencies during the New Deal set the stage for a broader and more enduring role for the federal government in economic planning and welfare. The federal government, once seen primarily as a regulatory body with limited intervention in the economy, became a central player in shaping the nation’s economic policies and providing for the welfare of its citizens. The New Deal marked a fundamental transformation in American governance, as the government took on the responsibility of managing economic stability, regulating industries, and ensuring that the basic needs of citizens were met through programs like Social Security and unemployment insurance. These agencies not only helped alleviate the immediate effects of the Depression but also laid the foundation for the modern welfare state, influencing the development of subsequent policies aimed at reducing poverty, promoting economic security, and addressing inequality. The New Deal’s expansion of the government’s role in economic planning and welfare fundamentally reshaped the American political landscape and set the stage for future debates about the appropriate size and scope of government intervention in the economy.

The Alphabet Agencies: A Vast Network of Change

Alphabet Soup

The “Alphabet Agencies” were a collection of federal organizations established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration during the New Deal era, designed to address the wide-ranging effects of the Great Depression. These agencies, often referred to by their initials (hence the term “alphabet”), played a central role in shaping Roosevelt’s response to the economic and social crisis that gripped the nation in the 1930s. From providing immediate relief to millions of unemployed Americans to implementing long-term reforms in the economy and financial systems, the Alphabet Agencies formed a comprehensive government-led effort to restore economic stability, social welfare, and public confidence in the nation’s institutions. The agencies spanned a diverse range of functions, from job creation and agricultural support to financial regulation and labor rights, each contributing to the New Deal’s overarching goals of relief, recovery, and reform.

The genesis of these agencies can be traced to the dire circumstances of the Great Depression, which, by the early 1930s, had left one-quarter of the American workforce unemployed, widespread poverty had taken hold, and the banking system was in collapse. Faced with these immense challenges, Roosevelt sought to empower the federal government to play a more active role in both the short-term relief of suffering and the long-term reform of the nation’s economic structure. His administration believed that only through decisive governmental intervention could the country overcome the depression’s economic and social toll. Roosevelt’s vision for the New Deal embraced a philosophy of direct federal action, embodied in these new agencies that became instrumental in alleviating the widespread suffering while also establishing new structures aimed at preventing future economic calamities.

The first group of Alphabet Agencies that emerged were focused on immediate relief efforts for the unemployed, homeless, and impoverished. One of the most notable agencies was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which was created in 1933 to provide jobs for young men in conservation projects across the country. The CCC employed more than 3 million men, who built national parks, planted trees, and constructed infrastructure in rural areas. These projects not only provided crucial employment opportunities but also helped to improve the nation’s environmental and public works infrastructure. Similarly, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was established in 1935 to provide jobs in a wide array of public works, including the construction of roads, bridges, schools, and hospitals. At its height, the WPA employed over 8 million Americans, making it one of the largest job-creation programs in history, and its projects remain part of the nation’s infrastructure today.

Alongside these immediate relief programs, the New Deal also created agencies focused on economic recovery and structural reforms. The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933 created the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which aimed to stabilize industrial prices and wages through codes of fair competition. By setting standards for wages, working conditions, and production levels, the NRA sought to encourage industrial recovery while providing workers with better rights and protections. However, the NRA was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935, but it set the stage for later labor and industrial reforms. Another major agency in the recovery efforts was the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), which was tasked with stabilizing farm prices and reducing crop surpluses by paying farmers to limit production. The AAA sought to raise agricultural prices and provide farmers with a more stable income, though its methods, including reducing the acreage of crops, were controversial and had mixed results, particularly among tenant farmers and sharecroppers.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), created by the Banking Act of 1933, was another crucial reform agency within the Alphabet Agencies. This agency was designed to restore confidence in the banking system by insuring individual deposits up to a certain amount, thus preventing the widespread bank runs that had contributed to the financial collapse of the early 1930s. The creation of the FDIC represented a fundamental change in the relationship between banks and the federal government, ensuring that individuals’ deposits were protected by the government, which had not been the case during the financial crisis. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), established in 1934, was another key regulatory agency that sought to prevent stock market abuses and protect investors. The SEC was tasked with enforcing laws against fraud, insider trading, and other dishonest practices in the securities markets, fundamentally altering the way Wall Street operated and fostering public confidence in the financial system.

In addition to these relief and recovery agencies, the New Deal established several agencies that addressed the broader question of labor rights and social welfare. The Wagner Act (also known as the National Labor Relations Act) of 1935 created the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which helped to enforce the rights of workers to unionize and engage in collective bargaining. This landmark legislation marked a turning point in labor rights, empowering unions to negotiate better wages and working conditions. The establishment of the Social Security Administration (SSA) in 1935 was perhaps the most transformative of all the New Deal reforms. The SSA introduced a national social insurance system, which provided pensions for the elderly, unemployment insurance for workers who lost their jobs, and aid to the disabled. This program created a social safety net that continues to serve millions of Americans today and formed the foundation of the modern welfare state.

Though each Alphabet Agency had its specific focus and goals, they were united by a common purpose: to stabilize the economy, protect vulnerable populations, and create a more regulated and equitable society. Roosevelt understood that the lasting impact of the Great Depression would require fundamental changes in the American economy and social structure, and the creation of these agencies was central to that vision. Through these agencies, the federal government took an unprecedented role in directly managing the nation’s economic and social life, setting the stage for future government involvement in areas like healthcare, education, and civil rights.

The creation of the Alphabet Agencies also represented a redefinition of the federal government’s role in relation to its citizens. Prior to the Depression, the government’s role was largely limited to overseeing defense, infrastructure, and basic governance. However, the New Deal and its associated agencies marked a shift towards an active government that would be involved in regulating economic activity, providing welfare for the needy, and overseeing the labor market. This expansion of government responsibilities, including its growing role in citizens’ everyday lives, led to a realignment of American politics, as the nation debated the appropriate extent of government intervention. Critics of the New Deal, particularly conservatives and business leaders, argued that Roosevelt’s approach threatened capitalism and individual freedoms. However, for many Americans, these agencies represented a lifeline during a time of unparalleled economic hardship, and they came to be seen as vital components of the nation’s recovery.

In retrospect, the Alphabet Agencies had a lasting impact on American society and governance, leaving a legacy that continues to influence federal policies today. While some of the agencies were short-lived or their programs were dismantled after the war, many of the New Deal institutions had a permanent effect on the American landscape. The FDIC, the SEC, the NLRB, and the SSA remain central to the nation’s financial, labor, and welfare systems. Moreover, the creation of these agencies helped solidify the idea that the federal government had a responsibility to ensure the well-being of its citizens, especially in times of economic crisis. The New Deal fundamentally reshaped the American political system, and the Alphabet Agencies were at the heart of this transformation.

Ultimately, the Alphabet Agencies represented the core of Roosevelt’s New Deal philosophy: a belief that the federal government must take an active role in the economy and social welfare to protect its citizens from the instability and suffering caused by the vagaries of the market. Through these agencies, Roosevelt aimed not just to provide short-term relief, but to create a new framework for economic governance that would provide long-term stability and prevent future economic disasters. Though the New Deal was controversial and its legacy debated, the Alphabet Agencies undeniably transformed the way Americans viewed their government and its role in their lives, setting the stage for the modern welfare state and the ever-expanding scope of federal responsibility.

Immediate Relief and Long-Term Reform

The General characteristics of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Alphabet Agencies can be characterized by their dual purpose: providing immediate relief to those suffering from the effects of the Great Depression and implementing long-term reforms aimed at preventing future economic crises. The immediate relief provided by these agencies was essential to alleviating the dire conditions millions of Americans faced in the 1930s, particularly high unemployment, poverty, and homelessness. Yet, alongside this short-term assistance, the New Deal sought to bring about lasting reforms that would stabilize the economy, regulate markets, and offer protections for vulnerable groups. This dual purpose of relief and reform was embedded within each agency’s mission and served to both mitigate the immediate suffering of the Depression while laying the groundwork for a more secure and equitable economic system.

One of the key characteristics of the Alphabet Agencies was their direct involvement in job creation, which was central to both relief and recovery efforts. Agencies such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) were created to employ millions of unemployed Americans in large-scale public works projects. These jobs provided an immediate source of income for individuals and families, helping them survive the hardships of the Depression. The CCC, for example, employed young men in environmental conservation projects, while the WPA focused on a wide range of infrastructure projects, including the construction of roads, bridges, schools, and hospitals. These efforts were aimed at alleviating the immediate suffering of the unemployed while simultaneously improving the nation’s infrastructure. The long-term reform aspect came from the vision that government involvement in public works would stimulate economic recovery by creating jobs, improving public services, and promoting economic growth in the process.

The dual purpose of immediate relief and long-term reform was also reflected in the agricultural sector, where several agencies were created to address both the short-term crisis of low crop prices and the long-term issues facing farmers. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) was designed to provide relief by paying farmers to reduce production in order to raise commodity prices. This aimed to help struggling farmers by reducing surpluses that were driving prices down, but it also sought to establish a more regulated agricultural market that would prevent future overproduction and ensure better price stability for farmers. At the same time, the long-term reform element was evident in the ways the government began to play a larger role in managing agricultural markets and addressing issues of rural poverty. While the AAA was controversial, particularly in its impact on tenant farmers and sharecroppers, its creation signified the government’s growing role in regulating agriculture as part of a broader vision of economic stability and sustainability.

In addition to relief and recovery, many Alphabet Agencies focused on regulatory reforms that would prevent the kind of economic excesses that led to the Great Depression. One of the most notable examples of this was the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which was established in 1934 to regulate the stock market and prevent the kinds of fraudulent practices that contributed to the 1929 crash. The SEC’s mission was to ensure fair trading practices, protect investors, and increase transparency in financial markets. This regulatory approach was a response to the abuses that had been allowed to flourish in the pre-Depression years, such as insider trading and market manipulation. The SEC’s long-term goal was to restore public confidence in the financial system and prevent the kind of speculative behavior that had undermined economic stability in the past. The creation of the SEC, alongside other regulatory bodies like the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), was emblematic of the New Deal’s emphasis on long-term reform through government regulation.

Finally, the creation of the Social Security Administration (SSA) in 1935 represents one of the most significant examples of the dual purpose of the Alphabet Agencies. The Social Security Act provided immediate relief to millions of elderly Americans, many of whom had been living in poverty during the Depression. The act established a system of social insurance that provided pensions for retirees, unemployment benefits for workers, and aid for the disabled. In the short term, this was a lifeline for those in immediate need of financial assistance. However, the long-term reform aspect was also crucial: Social Security established the foundation for the modern welfare state by creating a permanent social safety net for future generations. It represented a shift in the role of government, from being a minimal, reactive force to a proactive entity involved in the economic security of its citizens. Through Social Security and other welfare programs, Roosevelt sought to ensure that Americans would no longer face the same economic hardships that had caused so much pain during the Depression.

In sum, the general characteristics of Roosevelt’s Alphabet Agencies were defined by their twin missions of providing immediate relief and enacting long-term reforms. These agencies were designed to address the immediate crises caused by the Great Depression while also seeking to reshape the economic and social landscape to prevent future disasters. The New Deal represented a fundamental shift in the role of the federal government, from a passive observer to an active participant in managing the nation’s economy and providing for the welfare of its citizens. The agencies embodied this new approach by creating jobs, regulating industries, supporting farmers, protecting investors, and establishing social welfare programs that would have a lasting impact on American society. Through these dual objectives of relief and reform, the Alphabet Agencies helped to mitigate the worst effects of the Depression while laying the groundwork for a more stable and equitable future.

Major Agencies Created under FDR

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC)

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), one of the most significant of the New Deal agencies, was established in 1933 to address the dire problem of widespread unemployment during the Great Depression. Its primary purpose was to provide jobs for young, unemployed men between the ages of 18 and 25 through public works projects focused on the conservation and development of the nation’s natural resources. The CCC aimed to address two of the most pressing issues of the time: mass unemployment and the need for environmental restoration. For the millions of young men who found themselves without work and a future, the CCC offered both immediate employment and the opportunity to contribute to the nation’s well-being through meaningful work. The CCC’s efforts not only provided income to these men but also fostered a sense of purpose, discipline, and pride, as they worked in natural settings across the country.

The projects undertaken by the CCC were diverse, focusing primarily on conservation and infrastructure development in national parks, forests, and rural areas. The young men employed by the CCC participated in a variety of tasks, including reforestation, soil erosion control, park development, and the construction of trails, roads, and campgrounds in national parks. These efforts were crucial during a time when much of the nation’s environment had been overexploited, contributing to environmental degradation. The 1930s had witnessed widespread drought and the infamous Dust Bowl, which had devastated farmlands across the Midwest. Through the CCC’s work, millions of trees were planted, helping to prevent soil erosion and mitigate some of the environmental damage caused by poor agricultural practices. These conservation efforts were not only intended to restore the land but also to protect it for future generations, fostering a new sense of environmental stewardship in the United States.

The impact of the CCC was also felt in the communities where these young men were employed. Beyond the physical labor, the CCC helped to stimulate local economies, especially in rural and isolated areas. As the young men were paid for their labor, they sent a portion of their wages back home to support their families, which helped to alleviate some of the economic hardship that many families were facing during the Depression. The wages provided to CCC workers, though modest, also allowed them to develop skills and work experience that could serve them in future employment opportunities. Furthermore, the projects completed by the CCC helped to improve public infrastructure, such as roads and parks, which benefitted local communities and contributed to the overall recovery of the national economy. In this way, the CCC served as both a relief measure for individuals and a tool for broader economic recovery.

Another key aspect of the CCC’s purpose was the development of personal discipline and responsibility among the young men it employed. The program operated in a quasi-military structure, with workers living in camps under the supervision of military officers. This structure was designed not only to create a sense of order and discipline but also to instill a work ethic and a sense of community among the workers. Many of the men in the program came from poor backgrounds and had little to no job experience. Through the CCC, they were able to gain valuable work habits, learn new skills, and receive training in conservation-related fields, including forestry, engineering, and construction. The program also provided workers with education, with many camps offering basic schooling and vocational training. The combination of work, education, and structure allowed the men to improve their prospects for future employment, and many of them went on to use their CCC experience in subsequent careers, particularly in conservation and public works.

Finally, the CCC had a lasting impact on both the environment and the nation’s national parks and public lands. The program played a central role in the development of the United States’ national park system, helping to establish and expand parks that are still enjoyed today. The CCC’s work in building trails, visitor centers, and campgrounds, as well as in replanting forests and controlling erosion, laid the foundation for the growth and accessibility of the nation’s public lands. The aesthetic and recreational value of these areas was greatly enhanced by the efforts of the CCC, which allowed millions of Americans to experience nature in a more accessible and organized way. Moreover, the environmental legacy of the CCC lives on in the ongoing conservation work that has continued in many of the locations where the program operated. In essence, the CCC not only provided immediate relief and employment to young men during the Depression but also helped to preserve and protect the country’s natural heritage for generations to come, cementing its place as one of the most successful and enduring aspects of the New Deal.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) achieved remarkable success in addressing both immediate economic needs and long-term environmental goals during its operation from 1933 to 1942. One of its most significant achievements was its extensive reforestation efforts. The CCC planted over 3 billion trees, which were crucial in preventing soil erosion, particularly in the Dust Bowl region, where agricultural practices had caused severe damage to the land. These trees helped to stabilize the soil, restore nutrients to the land, and prevent further environmental degradation. In addition to its reforestation efforts, the CCC worked on other vital environmental projects, including flood control. By building dams, levees, and drainage systems, the CCC helped to control flooding in areas prone to heavy rains and river overflow. This work not only protected farmland and communities but also mitigated the risk of natural disasters that could further exacerbate the economic hardships of the time. The CCC’s reforestation and flood control projects laid the groundwork for the environmental sustainability of the country, addressing the immediate crisis caused by land degradation while ensuring long-term ecological stability.

Another major achievement of the CCC was its role in the development of national and state parks, which contributed to the expansion and preservation of the U.S. park system. The Corps constructed roads, bridges, campgrounds, hiking trails, and visitor centers in parks across the nation, making these natural spaces more accessible to the public. Many of these parks, such as Yellowstone, the Great Smoky Mountains, and Shenandoah, saw significant infrastructure improvements thanks to the efforts of the CCC. These developments not only provided jobs for thousands of young men but also contributed to the nation’s cultural and recreational heritage. Furthermore, the CCC’s employment program provided work for over 3 million young men, offering them a steady income during the Great Depression while also teaching valuable skills in areas like forestry, construction, and environmental conservation. The combination of job creation, environmental protection, and the enhancement of national parks made the CCC one of the most successful and enduring initiatives of the New Deal, with a lasting impact on both the country’s economy and its natural landscape.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA)

The Works Progress Administration (WPA), created in 1935 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt as part of his New Deal, was one of the most ambitious and wide-reaching agencies aimed at addressing the economic devastation caused by the Great Depression. The purpose of the WPA was primarily to provide immediate employment to the millions of Americans who were struggling to survive in an economy with rampant unemployment, poverty, and underutilized resources. It sought to provide jobs through public works projects that would improve the nation’s infrastructure, promote economic recovery, and bolster the morale of the American people. The WPA focused on employing individuals in a wide array of construction and service-related jobs, including the building of roads, bridges, schools, hospitals, and other public facilities, and offering services in the arts, education, and healthcare.

One of the most notable achievements of the WPA was its construction of critical infrastructure. Between 1935 and 1943, the WPA was responsible for building over 650,000 miles of roads, constructing 78,000 bridges, and completing over 1,000 airports. The agency also built more than 125,000 public buildings, such as schools, libraries, and hospitals. These projects not only provided immediate relief to millions of unemployed workers but also contributed to the long-term development of American infrastructure, creating a foundation for future economic growth. These improvements were particularly vital in rural and underserved areas, where infrastructure development had often been slow or inadequate. The WPA’s ability to bring jobs to these areas and improve their public works helped to promote more balanced regional development across the country.

In addition to its construction projects, the WPA had a profound impact on the cultural and artistic life of the United States. Recognizing the importance of arts and culture in uplifting a nation facing widespread despair, the WPA created programs specifically for artists, writers, actors, and musicians. The Federal Art Project (FAP), the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), the Federal Theatre Project (FTP), and the Federal Music Project (FMP) provided employment for thousands of creative professionals. These initiatives led to the creation of murals, plays, music compositions, literature, and more that reflected the lives, struggles, and dreams of ordinary Americans. Notable projects from this period include the iconic murals in public buildings, such as those in post offices, and the preservation of American folk music and history. The WPA’s investment in the arts helped to give the American people a sense of pride and unity during a challenging time, while also ensuring that cultural expressions were not lost to the economic constraints of the era.

The WPA’s achievements in education and social services were also significant. The agency employed teachers, social workers, and healthcare professionals to provide services to communities in need. Through the WPA, adult education programs were offered to help people gain basic literacy and job skills, while public health initiatives helped to address pressing issues like sanitation and medical care in underserved areas. The WPA’s provision of social services was particularly important for marginalized communities, including African Americans and women, who often faced greater barriers to employment during the Depression. The agency employed a diverse range of workers, offering opportunities to groups that had historically been excluded from many job sectors. This broader inclusion not only improved the well-being of these communities but also helped to lay the groundwork for future social safety nets and labor reforms in the U.S.

Despite facing criticism from some political factions and business interests, the WPA was ultimately one of the most successful programs of the New Deal, offering a combination of immediate relief and long-term benefits to the country. It helped to reduce the high levels of unemployment, with over 8 million people working for the WPA during its existence. The agency’s ability to employ so many Americans at a time of severe economic hardship was a testament to the scale and reach of Roosevelt’s commitment to tackling the Depression. Moreover, the infrastructure, artistic, and educational achievements that resulted from the WPA’s work left a lasting legacy on the nation. From the bridges and roads that continue to support the country’s transportation system to the artistic contributions that remain a vital part of America’s cultural heritage, the WPA’s impact has endured, making it one of the cornerstone achievements of the New Deal.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)

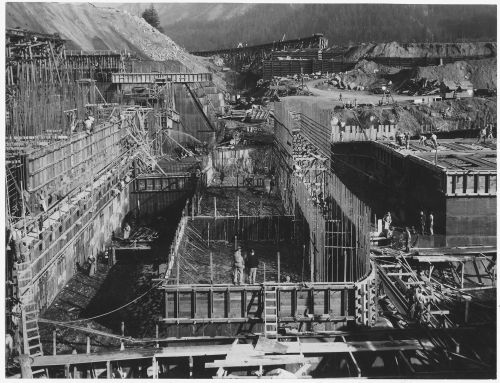

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), established in 1933 under the leadership of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was one of the most ambitious and far-reaching initiatives of the New Deal, designed to address both the economic and environmental challenges of the Tennessee Valley, a region hit hard by the Great Depression. The TVA’s primary purpose was to bring economic development to the Tennessee River Valley, which encompassed parts of seven states—Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. This area had long been plagued by poverty, underdevelopment, and a lack of infrastructure, exacerbated by frequent flooding and the depletion of natural resources, particularly soil erosion and deforestation. The TVA aimed to transform the region by providing a comprehensive solution to these issues through the construction of dams, the provision of affordable electricity, the improvement of agricultural practices, and the creation of jobs.

One of the TVA’s most important achievements was its extensive network of dams and reservoirs, which were built to control flooding, generate hydroelectric power, and improve navigation along the Tennessee River. Before the TVA, the region was frequently ravaged by floods, which destroyed homes, farms, and infrastructure. The TVA constructed more than 40 dams in the Tennessee Valley, significantly reducing the frequency and severity of floods. These dams not only protected communities from natural disasters but also served as sources of hydroelectric power, providing cheap and reliable electricity to rural areas that had previously lacked access to modern power grids. The creation of these dams marked a critical step toward modernizing the region’s infrastructure and was central to the TVA’s goal of economic development.

In addition to flood control and power generation, the TVA had a profound impact on agricultural development in the region. The valley’s land had been over-farmed and overgrazed, leading to widespread soil erosion, reduced crop yields, and widespread poverty. The TVA introduced modern agricultural techniques, such as soil conservation practices, crop rotation, and reforestation, to improve the quality and productivity of the land. The TVA provided farmers with the tools, knowledge, and financial support to implement these techniques, which helped to rejuvenate the soil and increase crop production. Through these efforts, the TVA not only improved agricultural output but also contributed to the stabilization of the rural economy in the Tennessee Valley, offering hope to farmers who had been struggling to survive during the Depression.

The TVA’s work also had significant social and economic benefits beyond the rural economy. By providing affordable electricity to homes and businesses, the TVA helped to modernize the region and improve the standard of living for thousands of families. Before the TVA, much of the Tennessee Valley was without electricity, which limited economic growth and hindered the quality of life for residents. The introduction of electricity to the area enabled businesses to grow, households to be more productive, and schools and hospitals to function more effectively. The availability of electricity also provided a foundation for industrial development, as businesses were able to use electric power to run machinery and produce goods more efficiently. This access to power was instrumental in the economic revitalization of the region and provided a model for rural electrification across the United States.

Perhaps one of the most enduring legacies of the TVA was its role in creating jobs and stimulating economic growth in a region that had been among the poorest in the country. During the construction of the TVA’s dams, power plants, and other infrastructure, thousands of workers were employed, many of whom were local residents who had been struggling to make ends meet during the Depression. The TVA also helped to stimulate local economies by attracting new industries to the area, providing training programs, and creating long-term employment opportunities in the power and agricultural sectors. By the end of the 1930s, the Tennessee Valley had become a model of how federal intervention and public works projects could revitalize a region that had been economically devastated. The TVA’s focus on both immediate relief and long-term development made it one of the most successful and lasting programs of the New Deal.

Overall, the Tennessee Valley Authority was a monumental achievement of the New Deal, combining flood control, electricity generation, agricultural reform, and job creation to transform a region that had long been mired in poverty and underdevelopment. The TVA’s integrated approach to economic development and environmental management provided a blueprint for future public works projects, demonstrating the potential of government intervention to improve the lives of ordinary Americans. Its achievements continue to resonate today, with the TVA still providing power to millions of people in the Tennessee Valley and remaining a symbol of the power of public investment in regional development.

The Public Works Administration (PWA)

The Public Works Administration (PWA), created in 1933 as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, was a pivotal agency aimed at addressing the catastrophic unemployment and underdevelopment caused by the Great Depression. Its primary purpose was to stimulate the economy by funding large-scale public works projects that would create jobs for millions of unemployed Americans, particularly in the construction and infrastructure sectors. The PWA was designed to support projects that would both provide immediate relief to workers and contribute to long-term economic recovery by investing in public infrastructure that would benefit the nation for decades to come. The PWA’s efforts were central to Roosevelt’s broader vision of using federal spending to revitalize the economy, stabilize industries, and lay the foundation for a more prosperous future.

One of the PWA’s most notable achievements was its extensive investment in infrastructure development, which had a lasting impact on the nation’s physical landscape. The agency funded the construction of thousands of miles of roads, bridges, airports, schools, hospitals, and government buildings, many of which are still in use today. Among its most iconic projects were the construction of the Hoover Dam, the Triborough Bridge in New York City, and the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State. These massive projects not only provided immediate jobs for workers but also addressed critical infrastructure needs that were essential for the long-term growth and development of the country. The PWA’s investments in public infrastructure helped to modernize the nation’s transportation systems, improve access to education and healthcare, and lay the groundwork for future industrial growth.

In addition to its large-scale infrastructure projects, the PWA played a critical role in revitalizing the construction industry, which had been devastated by the Depression. Prior to the creation of the PWA, the construction industry had ground to a halt due to the financial collapse and widespread unemployment. By providing substantial federal funding for public works projects, the PWA enabled construction companies to reopen, hire workers, and purchase materials, helping to re-establish a functioning construction sector. The agency’s efforts were particularly important in providing jobs for skilled laborers, such as carpenters, electricians, and masons, who had found themselves without work. The PWA’s ability to restart the construction industry was a vital step in the broader economic recovery, as it helped to stimulate demand for materials, revive supply chains, and reduce the unemployment rate.

The PWA was also significant for its emphasis on labor standards and the fair treatment of workers. In its early years, the PWA adopted policies that set wages at a fair, competitive level, ensuring that workers were paid decently for their labor. It also played a role in promoting the employment of minorities and women, although their participation in PWA projects was often limited. Still, the agency’s focus on fair wages and its insistence on contractors adhering to these standards set an important precedent for future labor policies and government contracting. The PWA also contributed to the development of labor relations by working closely with unions to ensure that workers were treated equitably, which had long-term implications for the labor movement in the United States. While not without its flaws, the PWA represented a commitment to improving working conditions during a time of widespread exploitation.

Perhaps one of the most enduring legacies of the Public Works Administration was its role in proving the effectiveness of federal intervention in addressing national economic crises. The PWA demonstrated that government spending on large-scale public works projects could have a positive impact on both immediate employment and long-term economic development. The success of the PWA helped to shape public attitudes toward federal involvement in the economy and paved the way for future New Deal initiatives and post-World War II public works programs. The agency’s accomplishments not only alleviated some of the immediate hardships caused by the Depression but also laid the foundation for a more robust and modern infrastructure system that supported American economic growth for generations to come. Through its investments in infrastructure, labor standards, and industry revitalization, the PWA was a key component of Roosevelt’s vision for a more equitable and prosperous nation.

The National Recovery Administration (NRA)

The National Recovery Administration (NRA), created in 1933 as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, was designed to combat the widespread economic turmoil caused by the Great Depression by stabilizing industries, reducing unemployment, and improving labor conditions. The NRA’s central purpose was to foster industrial recovery by promoting cooperation between business, government, and labor in a way that would stabilize prices, increase wages, and encourage fair competition. The NRA sought to create a more balanced economy by addressing issues such as excessive competition, low wages, and unsafe working conditions, all of which had contributed to the economic collapse. The government, through the NRA, aimed to create “codes of fair competition” that would establish industry standards for wages, prices, and working hours, thereby ensuring that businesses could operate more efficiently and workers were treated more fairly.

One of the key achievements of the NRA was the establishment of the industrial codes, which were designed to regulate various aspects of business operations. These codes set standards for wages, working hours, and conditions in different industries, and were meant to curb destructive practices like child labor, long working hours, and unfair wages. The codes were developed with input from business leaders, labor unions, and government officials, creating a framework for cooperation that had not existed before. Although the NRA struggled with enforcement and faced challenges from both businesses and labor groups, it succeeded in setting important precedents for regulating industry and protecting workers’ rights. These codes, which covered areas ranging from the textile industry to steel production, helped to raise wages and improve working conditions for many employees, marking a significant shift toward a more regulated and fairer economy.

Another important achievement of the NRA was its role in promoting unionization and improving labor rights. The agency supported the rights of workers to join unions and collectively bargain with employers, which had been difficult during the pre-Depression era due to weak labor protections and hostile employers. Through the NRA, the government took steps to formalize labor relations and give unions a more recognized place in the American workplace. Although the NRA itself did not directly organize unions, it encouraged businesses to negotiate with workers and adhere to collective bargaining agreements. The increased recognition of labor rights under the NRA laid the groundwork for later labor reforms, including the Wagner Act of 1935, which more fully guaranteed workers’ rights to unionize and bargain collectively.

Despite its achievements, the NRA faced significant challenges, including criticism from both business owners and labor groups. Many business owners resented the regulation of prices, wages, and working hours, feeling that it infringed on their ability to operate freely. On the other hand, some labor unions felt that the NRA’s codes did not go far enough in improving conditions for workers, and that the enforcement of codes was too weak. Furthermore, the NRA’s efforts to balance the interests of business and labor often resulted in compromises that left both sides dissatisfied. The agency also faced legal challenges, and in 1935, the Supreme Court ruled that the NRA was unconstitutional in the case of Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, citing the agency’s excessive delegation of power to the executive branch and its overreach into areas reserved for the states. This decision marked the end of the NRA, but many of its principles would be carried forward in future New Deal legislation, particularly in labor and industrial regulation.

The legacy of the NRA is mixed, but it played a crucial role in the development of the American economy and labor relations during the Depression. While it did not achieve all of its goals, it set significant precedents in the areas of labor rights, industry regulation, and government intervention in the economy. By establishing codes for fair competition and encouraging cooperation between business and labor, the NRA helped to lay the foundation for the later regulatory frameworks that would govern the American economy in the post-World War II era. The agency’s work also brought national attention to the need for labor reforms and fair practices in industry, creating a public demand for further action to protect workers. Ultimately, the NRA’s legacy influenced the future development of labor laws and economic policies, even though it was short-lived, and highlighted the importance of federal intervention in addressing economic instability.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was created in 1933 as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, in response to the widespread bank failures and the erosion of public trust in the banking system that had occurred during the Great Depression. The primary purpose of the FDIC was to restore confidence in the American financial system by insuring depositors’ savings, thereby preventing the panic-driven bank runs that had devastated banks throughout the Depression. The FDIC was designed to guarantee that even if a bank failed, individuals would not lose their deposits, which had been a major concern for many Americans at the time. This intervention was aimed at stabilizing the banking sector, which had suffered from mass withdrawals, a lack of liquidity, and an erosion of public faith in financial institutions.

One of the most significant achievements of the FDIC was its role in curbing the bank runs that had plagued the economy during the early 1930s. Prior to the creation of the FDIC, a series of bank failures had caused widespread panic among the public, as individuals feared for the safety of their savings. When depositors believed their banks were on the verge of collapse, they rushed to withdraw their funds, often exacerbating the situation and accelerating the bank’s failure. The FDIC’s establishment of federal deposit insurance—initially set at $2,500 per depositor—reassured the public that their money was safe even in the event of a bank’s insolvency. This assurance helped to stabilize the banking system and led to a decline in the frequency and severity of bank runs. The FDIC played a crucial role in restoring stability to the financial system and preventing further economic collapse.

Another major achievement of the FDIC was its contribution to the reform of banking practices and the establishment of new regulations that helped prevent future financial crises. The FDIC was part of a broader effort by the Roosevelt administration to overhaul the banking industry and create safeguards against risky banking practices that had contributed to the financial collapse. One of the key reforms was the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which, in conjunction with the FDIC, separated commercial banking from investment banking to reduce the risk of speculative investments that could threaten the stability of financial institutions. By insuring deposits and regulating the banking system more effectively, the FDIC helped to create a more secure financial environment, encouraging both consumers and businesses to trust the banking system once again.

The FDIC’s impact extended beyond restoring confidence in individual banks to the overall financial system. By providing insurance for deposits, the FDIC made it easier for the government to regulate and oversee banks, ensuring that they operated more responsibly and in accordance with new laws and regulations. As a result, the FDIC not only protected depositors but also contributed to the broader goal of stabilizing the national economy. It allowed banks to lend more confidently, knowing that the threat of widespread panic was mitigated, which in turn helped to stimulate economic growth and recovery during the Great Depression. The FDIC also conducted regular inspections of member banks to ensure that they were financially sound and adhered to the regulations, adding another layer of protection against future financial instability.