A rugged improvisational approach suited to the challenges of frontier life.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The American Old West, often romanticized as a land of rugged cowboys, lawless towns, and endless open plains, was also a challenging and often dangerous environment for the practice of medicine. Between the mid-19th century and the early 20th century, the expansion westward brought settlers, miners, ranchers, and soldiers into harsh and frequently isolated conditions. In this context, medical care was limited, improvisational, and often intertwined with the rough realities of frontier life. Understanding how medicine was practiced in the Old West offers valuable insight into the interplay between culture, environment, and the evolution of healthcare in America.

The Medical Landscape of the Frontier

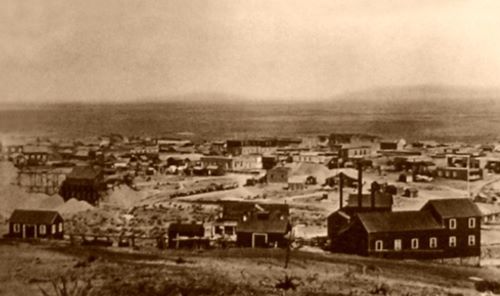

The American frontier during the mid-to-late 19th century presented a uniquely challenging environment for the practice of medicine. Unlike the established urban centers of the East Coast, where hospitals, trained physicians, and medical infrastructure were more prevalent, frontier towns were often rudimentary settlements with scarce medical resources. The rapid pace of westward expansion outstripped the availability of formally trained doctors, forcing many communities to rely on practitioners with limited or informal medical education. These physicians often operated with little more than a basic understanding of anatomy and a rudimentary medical kit, in conditions that lacked sterile environments or even adequate supplies. As a result, the quality of care was highly variable, and medical practice frequently depended on improvisation and experience rather than formal protocols. The scarcity of hospitals meant that most treatment took place in private homes or makeshift clinics, which further complicated patient care and recovery.1

Physicians on the frontier faced an array of health challenges that were often starkly different from those in more settled regions. Injuries were common, resulting from mining accidents, cattle drives, violent confrontations, and the rigors of travel across difficult terrain. Wounds from gunshot or animal attacks often led to infections such as gangrene, which, before the acceptance of germ theory, were poorly understood and rarely effectively treated. Infectious diseases also posed a significant threat. Cholera, smallpox, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and dysentery were widespread and could devastate communities with little warning. The combination of overcrowding in boomtowns and poor sanitation made these outbreaks frequent and deadly. Furthermore, nutritional deficiencies and harsh weather conditions weakened the settlers’ resistance to disease. The frontier doctor’s role thus extended beyond simple treatment; they were also often called upon to manage public health crises with little support.2

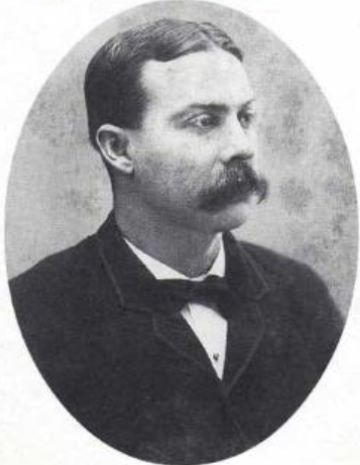

Medical training and knowledge during this period were inconsistent and often inadequate by modern standards. Medical education in the United States during the 19th century lacked standardization, with many doctors attending brief lectures or apprenticeships rather than rigorous medical schools. On the frontier, some physicians were self-taught or had minimal formal training, making them generalists who had to tackle everything from surgery to childbirth with limited expertise. This lack of specialization was both a necessity and a challenge, as frontier doctors needed to be adaptable but were also often overwhelmed by the breadth of medical problems they encountered. Despite these limitations, some frontier doctors became pioneers of medical practice under difficult conditions. For example, Dr. George E. Goodfellow of Tombstone, Arizona, was among the first in the United States to use antiseptic techniques and perform advanced surgeries on gunshot wounds, demonstrating how frontier necessity sometimes drove innovation.3

The reliance on patent medicines and traveling “medicine shows” further characterized the medical landscape of the Old West. Due to the scarcity of professional medical practitioners and the lack of access to proven remedies, many settlers turned to over-the-counter concoctions that promised cures for a wide variety of ailments. These patent medicines were often mixtures of alcohol, opium, or other substances with little therapeutic value and could be dangerous. Traveling medicine shows combined entertainment with salesmanship, promoting these remedies while providing a spectacle for frontier audiences. Though these shows filled a gap in healthcare access, they also contributed to medical misinformation and sometimes caused harm. Nevertheless, the presence of such practices underscores the demand for healthcare in the absence of established medical institutions.4

Women and Indigenous healers played indispensable roles in frontier medicine. In many remote settlements, trained doctors were unavailable, and women acted as midwives, nurses, and caregivers, administering home remedies and herbal medicines passed down through generations. Their knowledge often represented the primary form of healthcare for many families. Indigenous peoples, too, maintained traditional healing practices based on herbal medicine, spiritual rituals, and holistic care, which sometimes intersected with settler medicine, although frequently these indigenous practices were marginalized or dismissed by European-American settlers. The frontier’s medical landscape was thus a mosaic of varying traditions and approaches, shaped as much by cultural exchange and necessity as by formal scientific progress. This diversity highlighted the adaptive nature of healing on the frontier and the critical role of community in sustaining health under difficult circumstances.5

Common Medical Challenges

The practice of medicine in the American Old West was beset by a wide range of common medical challenges, many of which stemmed from the harsh environmental conditions and the rough nature of frontier life. Physical injuries were among the most frequent medical issues doctors faced. The dangers of mining accidents, cattle drives, horse riding, and frequent gunfights meant that traumatic wounds such as fractures, lacerations, and gunshot wounds were daily occurrences. Often, these injuries were severe, and treatment options were limited. Amputation was a common procedure when limbs became badly infected or crushed, but the lack of anesthesia and antiseptic techniques meant that surgery was risky and painful. Moreover, the shortage of trained surgeons meant that many procedures were performed by general practitioners or even laypeople, increasing the risk of complications.6

Infectious diseases presented another formidable challenge on the frontier. Epidemics of cholera, smallpox, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and dysentery periodically devastated frontier populations. The conditions in many boomtowns and mining camps—marked by overcrowding, poor sanitation, and limited clean water—created ideal environments for the spread of these illnesses. Cholera outbreaks, in particular, were notorious for their rapid onset and high mortality. Without effective treatments or vaccinations during much of this period, controlling these diseases was nearly impossible. Doctors often resorted to palliative care, trying to alleviate symptoms without being able to address the underlying infection. The limited understanding of germ theory until the late 19th century hampered efforts at prevention and effective intervention.7

Compounding these issues were nutritional deficiencies and exposure to extreme weather conditions, which weakened settlers’ immune systems and increased their vulnerability to illness. Many frontier settlers suffered from malnutrition due to poor diets, especially during the harsh winters or when supply lines were interrupted. Vitamin deficiencies such as scurvy were not uncommon, further impairing wound healing and overall health. The extreme cold, heat, and dust storms that characterized much of the western landscape also contributed to respiratory problems and infections. These environmental factors made both prevention and treatment of illness more difficult and necessitated a holistic approach to healthcare that was rarely available on the frontier.8

The limited knowledge of infection and antisepsis during the 19th century greatly affected treatment outcomes. The frontier medical community was slow to adopt germ theory, and antiseptic surgical techniques were often absent. This ignorance led to a high incidence of post-operative infections, including gangrene, which was frequently fatal. Wound care commonly involved poultices and herbal remedies, many of which had little scientific basis. Doctors often had to rely on trial and error, and the outcomes varied widely. It was not until figures like Goodfellow in the late 1800s began pioneering sterile techniques in frontier hospitals that mortality rates began to improve.9

The mental and emotional toll of frontier life also presented significant medical challenges, though they were often overlooked. The isolation, physical hardships, and constant exposure to violence and death contributed to psychological distress among settlers and soldiers alike. However, mental health was poorly understood, and there were few if any treatments available. Conditions that today would be diagnosed as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder were often ignored or attributed to moral failings. The lack of social support systems and professional psychiatric care meant that many sufferers endured their symptoms in silence. This psychological dimension of frontier medicine adds another layer of complexity to understanding the full scope of medical challenges faced during this era.10

Frontier Doctors: Jacks-of-All-Trades

Frontier doctors in the American Old West were quintessential jack-of-all-trades, tasked with providing a wide array of medical services in an environment that was often unforgiving and resource-poor. Unlike their urban counterparts who might have specialized in surgery, obstetrics, or internal medicine, frontier physicians had to be generalists, capable of diagnosing and treating everything from infectious diseases to traumatic injuries. This breadth of responsibility arose not just from necessity but from the realities of frontier life, where the nearest doctor could be hundreds of miles away, and medical resources were limited. Doctors had to be skilled in delivering babies, setting broken bones, performing amputations, and managing chronic illnesses with equal proficiency. Their work was as much about improvisation and practical knowledge as it was about formal medical training.11

Many frontier doctors possessed only modest formal education by today’s standards. In the mid-19th century, medical education in the United States was in a transitional phase, lacking uniform standards or rigorous licensing requirements. Some practitioners learned through apprenticeships with more experienced doctors, while others attended short courses or proprietary medical schools that varied widely in quality. On the frontier, these disparities became less significant as survival and practical experience took precedence over academic credentials. The pressing demands of treating a diverse population with limited supplies meant that doctors often learned “on the job,” adapting traditional remedies and experimenting with new techniques. This hands-on experience was crucial, as frontier doctors frequently operated without the benefit of laboratories, imaging, or specialist consultation.12

One of the defining aspects of frontier medicine was the necessity for adaptability and innovation. For example, many doctors became adept at performing surgeries under difficult conditions, often without anesthesia or sterile environments. Some, like Goodfellow in Tombstone, were early adopters of antiseptic techniques and pioneers in treating gunshot wounds, despite the challenges of limited resources and rugged surroundings. These physicians also made use of whatever materials were available—improvising surgical instruments, crafting splints from wood or metal scraps, and utilizing local plants as rudimentary medicines. Their ability to innovate under pressure was critical to patient survival, and many frontier doctors earned reputations for bravery and skill that spread far beyond their local communities.13

Beyond clinical skills, frontier doctors often served multiple roles within their communities. They were not only healthcare providers but also public health officials, educators, and community leaders. In settlements where government infrastructure was minimal or absent, doctors took responsibility for managing outbreaks of infectious diseases, advocating for sanitation improvements, and educating the public about hygiene and preventive care. They also provided counseling and comfort in times of crisis, becoming trusted figures in socially and economically unstable environments. Their roles extended into social and sometimes legal realms, as they might be called upon to provide expert testimony or serve as coroner. This multifaceted engagement made frontier doctors central to community cohesion and survival.14

Despite their crucial role, many frontier doctors struggled with the limitations imposed by their circumstances. They often worked long hours, faced shortages of medicines and supplies, and endured the emotional strain of caring for patients with little hope of successful outcomes. Isolation and the demands of frontier life also affected their personal well-being, with some succumbing to burnout or leaving the profession altogether. Nonetheless, the legacy of these jack-of-all-trades physicians is evident in the foundations they laid for rural and emergency medicine in America. Their blend of adaptability, broad expertise, and commitment under challenging conditions helped shape the uniquely American identity of medical practice on the frontier.15

The Role of Women and Midwives

In the American Old West, women played a crucial and multifaceted role in the provision of medical care, often serving as the primary caregivers within families and communities. Formal medical professionals were scarce, and the frontier’s isolation made access to doctors difficult or impossible for many settlers. In this context, women’s knowledge of home remedies, herbal medicine, and practical nursing was essential to the survival and health of frontier families. Women often learned medical skills through informal means—passed down from mothers, neighbors, or Indigenous healers—and took on the responsibility of managing illnesses, injuries, and childbirth in the absence of professional care. Their caregiving extended beyond physical health, encompassing emotional support and psychological comfort during times of illness and hardship.16

Midwives, in particular, occupied a vital niche in frontier medicine, providing care for pregnant women and delivering babies under often challenging circumstances. With hospitals virtually nonexistent in many frontier areas, childbirth was primarily a domestic event overseen by midwives, who combined traditional knowledge with practical experience. Their role extended beyond delivery to prenatal and postnatal care, ensuring the health of both mother and child. Midwives frequently relied on herbal remedies, massage, and other non-invasive techniques to ease labor and prevent complications. Despite occasional criticism from male physicians who sought to professionalize and medicalize childbirth, midwives remained indispensable in frontier communities, often saving lives where formal medical intervention was unavailable.17

The contribution of women and midwives also intersected with Indigenous medical practices, which influenced frontier healing traditions in significant ways. Many frontier women learned about the medicinal properties of local plants and natural resources from Native American healers, whose expertise in herbal medicine was often respected, if not formally acknowledged. This cross-cultural exchange enriched the medical landscape of the West and provided settlers with a broader repertoire of treatments for common ailments and injuries. However, Indigenous healing practices were sometimes marginalized or suppressed due to prevailing cultural biases and the expansion of Western medicine. Still, the blending of these traditions underscored the adaptability and resourcefulness of women and midwives in frontier healthcare.18

In addition to direct patient care, women on the frontier were often involved in public health efforts, especially in organizing community responses to disease outbreaks and promoting sanitation. They were key figures in educating families about hygiene, nutrition, and preventive measures, which were critical in environments prone to epidemics such as smallpox and cholera. Women’s social roles and networks enabled them to disseminate health information effectively and mobilize support during crises. Their work in this domain laid the groundwork for more formalized public health initiatives in later years and highlighted the importance of women as health educators and advocates within their communities.19

Despite their indispensable contributions, women and midwives faced significant social and professional obstacles in the medical field. The rise of professional medicine in the late 19th century, dominated by formally trained male doctors, often marginalized women’s traditional roles, dismissing midwifery as unscientific or inferior. Legal restrictions and licensing laws increasingly regulated childbirth and medical practice, limiting women’s autonomy and professional opportunities. Nonetheless, many women continued to provide essential care, particularly in rural and frontier areas where formal medical services remained scarce. Their resilience and expertise helped sustain frontier communities through the physical and social hardships of Western expansion and left a lasting legacy in the development of American medicine.20

Advances and Legacy

The American Old West, often perceived as a rugged and lawless frontier, was also a site of significant medical innovation and advancement. Despite limited resources, isolation, and challenging conditions, frontier doctors and medical practitioners developed practical techniques and strategies that improved patient outcomes and influenced broader medical practice in the United States. One notable advance was the pioneering use of antiseptic surgical methods by doctors such as Goodfellow in Tombstone. Goodfellow’s innovative approach to treating gunshot wounds using early sterilization techniques helped reduce infections and save lives in a period when germ theory was still gaining acceptance in medical circles. His work demonstrated the critical importance of hygiene in surgery and laid the groundwork for safer surgical practices on the frontier and beyond.21

In addition to surgical innovations, frontier medicine contributed to the development of emergency and trauma care tailored to the realities of a volatile environment. The frequent occurrence of traumatic injuries from mining accidents, gunfights, and transportation mishaps required doctors to become adept at rapid assessment and intervention. Techniques such as quick amputations, wound debridement, and the use of makeshift splints were refined out of necessity. These experiences helped shape the early practices of trauma medicine in the United States and influenced military medicine during later conflicts. The frontier’s demand for versatile and efficient medical responses spurred a pragmatic approach to care that prioritized saving life and limb in difficult circumstances.22

The role of women and midwives during this era also contributed to lasting changes in obstetrics and public health. As midwives attended the majority of births on the frontier, their practical knowledge informed both prenatal and postnatal care, emphasizing the importance of hygiene, nutrition, and maternal support. These lessons helped shift childbirth practices toward safer, more attentive care, even as the medical establishment sought to professionalize and regulate childbirth. Moreover, women’s involvement in community health initiatives—such as sanitation efforts, vaccination campaigns, and disease education—helped establish early public health models that would later be formalized in urban centers. The legacy of women’s medical labor on the frontier is reflected in the gradual expansion of nursing and public health professions in the decades following Western settlement.23

Medical practitioners on the frontier also contributed to the institutional development of healthcare in the West by founding hospitals, training schools, and professional organizations. As towns grew and stabilized, doctors recognized the need for permanent medical facilities and formalized education to improve care quality. Some frontier doctors transitioned from itinerant practitioners to hospital founders and educators, helping to establish the medical infrastructure that supported expanding populations. These institutions preserved frontier medical knowledge and adapted it to new technologies and scientific advances. The establishment of these facilities marked a turning point, bridging the gap between frontier improvisation and modern medical professionalism in the region.24

The legacy of medical practice in the American Old West extends beyond specific innovations to encompass a broader cultural influence on American medicine. The frontier spirit of resilience, adaptability, and practical problem-solving informed later developments in rural medicine, emergency response, and public health outreach. The experience of frontier doctors in managing diverse medical challenges with limited resources anticipated the modern emphasis on community-based care and holistic treatment approaches. Furthermore, the stories of pioneering physicians and midwives from this era have become part of the American medical mythology, inspiring future generations of healthcare providers. Ultimately, the medical advances and practices developed in the Old West represent an important chapter in the evolution of American healthcare.25

Conclusion

The practice of medicine in the American Old West was shaped by necessity, scarcity, and a pioneering spirit. It combined elements of traditional healing, emerging medical science, and a rugged improvisational approach suited to the challenges of frontier life. While many suffered from inadequate care and harsh conditions, the resourcefulness of frontier doctors, midwives, and communities laid foundations for the development of medical practice in the expanding United States. Their stories remind us how medicine adapts and evolves in response to the environment and cultural context, often in ways that shape the course of history.

Appendix

Endnotes

- James C. Mohr, Doctors and the Law: Medical Jurisprudence in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 48–52.

- Richard H. Shryock, The Development of Modern Medicine: An Interpretation of the Social and Scientific Factors Involved (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1936), 189–193.

- Mary C. Gillett, The West: An Illustrated History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 125–127; R. Michael Wilson, “George Goodfellow: The Gunfighter’s Surgeon,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 40, no. 3 (1985): 283–294.

- James Harvey Young, The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America before Federal Regulation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961), 101–110.

- Katherine A. Dettwyler, “Indigenous Medicine and Healing Practices on the American Frontier,” American Anthropologist 97, no. 4 (1995): 707–718; Ann B. Ross, Midwives of the Frontier (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), 53–59.

- Susan R. Schrepfer, The Fight to Save the Redwoods: A History of Environmental Reform, 1917–1978 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), 85–87.

- Alfred W. Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 22–25; Michael R. Taylor, The American West and the Public Health (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995), 114–117.

- Philip J. Pauly, Fruits and Plains: The Horticultural Transformation of America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 133–137.

- Wilson, “George Goodfellow,” 288-291.

- Katherine Ott, Fools for Scandal: How Psychiatry Transformed the American Understanding of Mental Illness (New York: Free Press, 1996), 67–70.

- Gillett, The West, 130-135.

- Mohr, Doctors and the Law, 55-60.

- Wilson, “George Goodfellow,” 288-292.

- Susan L. Smith, “Physicians as Community Leaders on the Frontier,” Western Historical Quarterly 31, no. 4 (2000): 435–440.

- Katherine A. Dettwyler, Frontier Medicine and Public Health (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 102–108.

- Ross, Midwives of the Frontier, 10-15.

- Linda L. Richards, Women and Midwifery in the American West (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993), 45–52.

- Dettwyler, “Indigenous Medicine and Healing Practices on the American Frontier,” 710-712.

- Susan L. Smith, “Women’s Role in Public Health on the Frontier,” Western Historical Quarterly 29, no. 3 (1998): 297–303.

- Elaine A. Kinsella, Women in Medicine: A History of Struggle and Triumph (New York: Routledge, 2001), 123–130.

- Wilson, “George Goodfellow,” 288-292.

- Dettwyler, Frontier Medicine and Public Health, 115-120.

- Richards, Women and Midwifery in the American West, 60-65.

- Gillett, The West, 145-150.

- Smith, “Physicians as Community Leaders on the Frontier,” 438-440.

Bibliography

- Crosby, Alfred W. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Dettwyler, Katherine A. Frontier Medicine and Public Health. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

- Dettwyler, Katherine A. “Indigenous Medicine and Healing Practices on the American Frontier.” American Anthropologist 97, no. 4 (1995): 707–718.

- Gillett, Mary C. The West: An Illustrated History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000.

- Kinsella, Elaine A. Women in Medicine: A History of Struggle and Triumph. New York: Routledge, 2001.

- Mohr, James C. Doctors and the Law: Medical Jurisprudence in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Ott, Katherine. Fools for Scandal: How Psychiatry Transformed the American Understanding of Mental Illness. New York: Free Press, 1996.

- Pauly, Philip J. Fruits and Plains: The Horticultural Transformation of America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Richards, Linda L. Women and Midwifery in the American West. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993.

- Ross, Ann B. Midwives of the Frontier. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989.

- Schrepfer, Susan R. The Fight to Save the Redwoods: A History of Environmental Reform, 1917–1978. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003.

- Shryock, Richard H. The Development of Modern Medicine: An Interpretation of the Social and Scientific Factors Involved. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1936.

- Smith, Susan L. “Physicians as Community Leaders on the Frontier.” Western Historical Quarterly 31, no. 4 (2000): 432–445.

- Smith, Susan L. “Women’s Role in Public Health on the Frontier.” Western Historical Quarterly 29, no. 3 (1998): 290–310.

- Taylor, Michael R. The American West and the Public Health. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

- Wilson, R. Michael. “George Goodfellow: The Gunfighter’s Surgeon.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 40, no. 3 (1985): 283–294.

- Young, James Harvey. The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America before Federal Regulation. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.09.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.