Housing assistance in ancient Rome was not systematic, universal, or ideologically grounded in rights.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Urban Strain in the Imperial Capital

In the crowded heart of the Roman Empire, the question of shelter transcended architecture and intersected with politics, social stability, and imperial ideology. The city of Rome—teeming with over a million inhabitants at its height—was a place of dramatic contrasts. Lavish aristocratic homes coexisted with crumbling insulae where the urban poor lived under the constant threat of fire, collapse, and eviction. While Rome never developed a centralized welfare system, the state and its magistrates intervened in housing matters through a variety of ad hoc and indirect means. These interventions, ranging from emergency aid and rebuilding to grain subsidies and informal patronage, reveal a political culture attuned to the dangers of urban neglect, even as it fell short of providing housing as a civic right.

The Grain Dole as Indirect Housing Support

The most consistent and systematized form of public assistance in ancient Rome was the annona, or grain dole. While primarily designed to combat hunger and stabilize civil order, the annona also functioned as an indirect form of housing assistance. By providing subsidized or free grain to qualifying citizens—sometimes as many as 300,000 men under Augustus—it effectively freed up household income that might otherwise have been spent on food, allowing the poor to afford rent in a housing market with few protections.1 The state thereby propped up the urban poor without constructing housing directly, embedding social stability within the fabric of daily sustenance.

This system helped perpetuate urban residency for Rome’s poorest classes, enabling their participation in civic life and preventing mass migration out of the city. Yet this form of relief was vulnerable to disruption and often politicized, especially during transitions of power or grain shortages. Still, as Peter Garnsey observes, the annona was a critical economic cushion that indirectly helped stabilize both population and housing by reducing the pressure of subsistence costs.2

Imperial Intervention After Urban Catastrophes

Rome’s densely packed neighborhoods, often built from cheap timber and rising several stories high, were chronically vulnerable to fire and collapse. The most famous of these disasters—the Great Fire of 64 CE—offered a rare instance of direct imperial housing relief. After the fire swept through the capital, Emperor Nero undertook a significant rebuilding program. According to Tacitus, Nero not only instituted new building codes that mandated the use of non-flammable materials and limited building heights, but he also provided financial assistance through interest-free loans and opened his own gardens as temporary shelter for the displaced.3

This reconstruction effort was as much a political maneuver as a humanitarian one. By offering shelter and reforming the housing code, Nero sought to present himself as a paternal figure and to restore civic order. Other emperors, such as Tiberius and Domitian, enacted similar post-disaster responses, providing funding and resources for rebuilding neighborhoods ravaged by fires or earthquakes. These interventions, though irregular, served to stabilize Rome’s housing supply during moments of crisis and projected the image of an emperor attentive to his people’s needs.

Regulatory Oversight and the Role of the Aediles

Apart from disaster response, Rome’s magistrates undertook limited but meaningful efforts to regulate housing conditions in the city. Chief among these were the aediles, elected officials responsible for urban maintenance, public order, and market supervision. Aediles were empowered to inspect buildings, enforce limits on the height of insulae, and impose penalties for unsafe or collapsing structures.4 Although enforcement was likely inconsistent and subject to elite influence, the existence of such oversight indicates that the state recognized the dangers of unregulated housing.

New regulations introduced under Augustus, and later reinforced by Nero, attempted to standardize construction practices and curb the most hazardous tenement designs. While these rules did not improve housing quality dramatically, they reflected a state interest in preventing urban disasters and, by extension, political instability.

Land Grants and Housing for Veterans

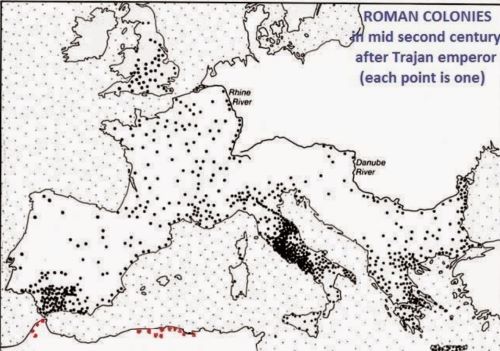

Beyond Rome itself, the Roman state occasionally provided land and housing support to soldiers through the establishment of coloniae. These military settlements, often located in recently conquered or strategically important regions, offered retiring legionaries plots of land and assistance in constructing homes. The policy served multiple functions: it rewarded military service, reduced the economic burden of reintegrating veterans into civilian life, and expanded Roman cultural and political influence throughout the provinces.5

This type of housing support was tied not to poverty but to service, and while it did not alleviate urban housing shortages, it illustrates the Roman state’s understanding of shelter as a form of compensation and integration. The settlements helped to prevent the urban overcrowding that might otherwise occur if large numbers of veterans returned to Rome without support.

Employer-Linked Housing and Public Lodging

Evidence from cities like Pompeii and Ostia suggests that some state-owned buildings may have been used to house public employees, imperial slaves, or officials. Converted warehouses and barracks appear to have served as temporary lodging in certain cases. These arrangements were not widespread, and their identification is often debated among archaeologists, but they represent a form of employer-provided housing embedded within the imperial bureaucracy.6

These dwellings were likely basic and transitional in nature, but they served a functional role in supporting Rome’s sprawling administrative and logistical apparatus. The fact that the state recognized the need to house its own labor force, however modestly, adds another layer to our understanding of Roman housing policy.

Patronage Networks as Informal Housing Support

In the absence of institutional welfare, many poor Romans relied on patron-client relationships for housing support. Wealthy patrons could provide temporary lodging, cover rent payments, or help secure tenancies for clients in exchange for political loyalty or services rendered. This support system, deeply embedded in Roman social hierarchy, functioned as a form of informal housing aid—highly personalized, unequal, and dependent on the benevolence or ambition of the patron.7

While this system lacked transparency and guaranteed access, it nonetheless played a critical role in enabling the poor to survive in the capital. As Richard Saller has argued, the patronage system was not merely symbolic but had tangible economic consequences, including in areas like housing, legal aid, and food provision.8

Conclusion: Shelter and Sovereignty in the Roman Cityscape

Housing assistance in ancient Rome was not systematic, universal, or ideologically grounded in rights. Instead, it emerged piecemeal, through a combination of public relief, disaster response, regulatory efforts, and personal patronage. These interventions reflected a pragmatic recognition of the political and social importance of shelter, particularly in a city where unrest could erupt from the discontent of the urban poor. The Roman state never developed a fully-fledged housing policy, but its efforts—however limited—demonstrate that the issue of shelter was not overlooked.

In responding to crises, regulating markets, and managing the built environment, Roman leaders walked a careful line between laissez-faire indifference and paternalistic intervention. In doing so, they helped sustain one of the ancient world’s most complex urban centers, not through ideals of equity or entitlement, but through strategies of stability and spectacle. The Roman approach to housing assistance reveals as much about the empire’s governance as it does about its architecture, reminding us that in every age, the question of where people live is bound up with the question of how they are ruled.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Garnsey, Famine and Food Supply, 231–34.

- Ibid.

- Tacitus, Annals 15.39–43.

- Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City, 32–35.

- Keppie, Colonial Veterans, 90–94.

- Laurence, Roman Pompeii, 64–66.

- Saller, Personal Patronage, 14–17.

- Ibid., 15.

Bibliography

- Garnsey, Peter. Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Keppie, Lawrence. Colonial Veterans and the Spread of Roman Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1983.

- Laurence, Ray. Roman Pompeii: Space and Society. London: Routledge, 1994.

- Saller, Richard P. Personal Patronage under the Early Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Stambaugh, John E. The Ancient Roman City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988.

- Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome. Translated by Michael Grant. London: Penguin Classics, 1996.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.02.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.