It shook assumptions, invited new models, and reminded early sixteenth-century Europeans that life itself (breath, motion, sound) could be unsettled by a cough that came without warning and left without cure.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When the World Sneezed for the First Time

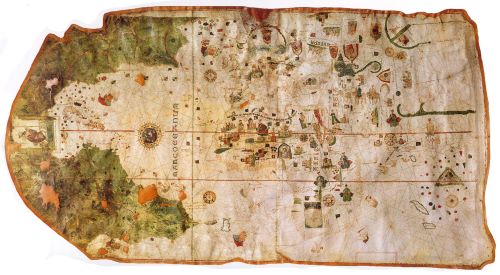

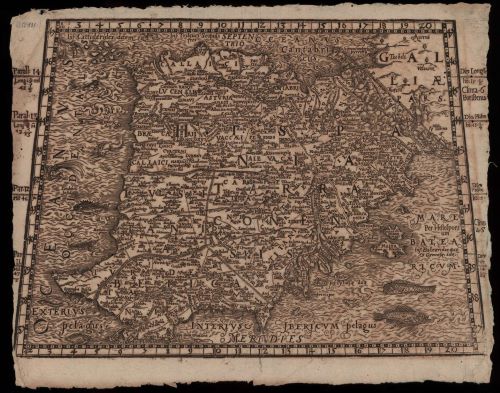

In the summer of 1510, a peculiar illness swept across Europe with startling uniformity. Beginning somewhere near the eastern Mediterranean and rippling outward into the heartlands of Christendom, it moved with a velocity and reach that puzzled contemporaries and has intrigued historians ever since. To early sixteenth-century observers, this sickness (variously called coqueluche, catarrh, or tussis) seemed like a visitation of divine wrath or a sudden disorder of the humors. To modern scholars, it is recognized as the first clearly documented influenza pandemic in European history.

The outbreak was not merely medical. It intersected with shifting ideas of the body, the rise of printing, and the political instability of a Europe on the cusp of reformation and empire. In this sense, the pandemic serves as a hinge between medieval patterns of plague panic and early modern efforts to narrate and understand disease. This essay explores the 1510 flu not simply as a biological event but as a moment of epistemic rupture, in which illness forced reflection, disrupted rhythms, and revealed the fragility of bodies, kingdoms, and knowledge systems alike.

The Shape of a Sickness: Symptoms, Spread, and Surveillance

Mapping Contagion Before Germs

Contemporary descriptions of the 1510 outbreak are surprisingly consistent despite the absence of shared diagnostic criteria. Physicians, clerics, and chroniclers from Italy, France, Spain, and England recorded an illness characterized by abrupt onset, violent coughing, fever, and overwhelming fatigue. The illness often incapacitated its victims for days, though mortality was relatively low.1

What is striking is the speed. The flu reportedly reached Paris in a matter of weeks and blanketed most of western Europe by late summer. Giovanni Manardo, court physician to Alfonso I d’Este in Ferrara, observed that entire households fell ill simultaneously, with symptoms appearing almost immediately after exposure.2 In an era before microscopes and germ theory, this simultaneity posed a conceptual challenge. How could illness pass invisibly and so quickly, ignoring borders and defying the slow pace of conventional contagion?

The mystery prompted speculation. In Spain, astrologers attributed the outbreak to an unfavorable alignment of Jupiter and Saturn. In Paris, others blamed corrupted air rising from the marshes. Still others saw divine punishment for growing heresy or moral laxity. These interpretations were not irrational within their own frameworks. They represented a complex blend of Galenic medicine, medieval theology, and natural philosophy attempting to account for a disease that refused to behave like known afflictions.3

Naming the Unseen

The term coqueluche, likely derived from the French for “hood” or “cowl, entered common use during this pandemic, and its etymology is telling. One theory holds that it referred to the head coverings worn by patients driven to bed, while another suggests it echoed the sound of coughing.4 In either case, the name reflected a linguistic groping toward a visible signifier for an invisible assailant. What could not be seen or understood was at least to be named.

This emphasis on naming would persist. The 1510 flu, though not called “influenza” until the eighteenth century, marked the start of a tradition in which disease was defined not by its pathology but by its perceived behavior. It was a turning point from the era of “fevers” and “fluxes” toward a taxonomy of illness based on pattern, not just symptom.

Bodies and Books: The Flu and the Early Modern Epistemology of Illness

Printing Pandemics

The 1510 pandemic occurred within decades of the printing press’s explosive spread across Europe. Though not yet fully medicalized, the pandemic did generate textual responses that reflected changing relationships between observation, authority, and publication. Short treatises, pamphlets, and physician’s letters circulated widely, offering advice, herbal remedies, and often moral commentary.5

Printing facilitated more than the dissemination of treatments. It helped forge a shared experience of the pandemic across disparate geographies. Where previous plagues had often been localized and chronicled in manuscript form, the 1510 flu became an event whose contours were sketched in print, albeit unevenly. The disease, much like the printed word, traveled fast and left a residue in the archival record.

These early publications also reveal the tensions between vernacular knowledge and learned authority. In cities like Lyon and Venice, printers published both university-sanctioned medical advice and lay-authored accounts. The coexistence of these voices suggests a loosening of epistemic control. Disease, it seemed, no longer belonged solely to the elite physician or ecclesiastical commentator.6

Humor, Balance, and the Unbalanced World

While we now understand influenza as a viral respiratory illness, sixteenth-century medicine interpreted it through the lens of humoral imbalance. Coughing signified excess phlegm. Fever pointed to choler. Exhaustion implied a drainage of vital spirits. The flu was not an invading agent but a misalignment of the body’s innate elements, often prompted by seasonal or celestial changes.

The widespread use of emetics, purgatives, and bloodletting to “rebalance” patients underscores how this framework guided treatment. Yet the 1510 pandemic also revealed the inadequacy of humoral theory when faced with rapid transmission and apparent person-to-person spread. Physicians began to speak of “seeds” of disease and airs that could carry illness, not fully abandoning Galen, but hinting at his conceptual limits.7

Royal Coughs and Peasant Beds: Social Reach of the 1510 Pandemic

A Democratic Disease

The 1510 flu struck across social strata. Nobles, merchants, friars, and field laborers all succumbed, often simultaneously. In England, the court of Henry VIII reported cases, and diplomatic correspondence between French and Italian courts noted that “even kings sneeze.”8 Unlike plague, which often began in poorer quarters and ascended upward, the flu appeared indifferent to status.

This democratization of illness was unsettling. It blurred distinctions. That the king and cobbler might share symptoms, or that an archbishop could be bedridden beside a miller, challenged existing assumptions about the moral and bodily superiority of elites. The body politic, quite literally, coughed in unison.

Disrupted Work and the Economy of Fatigue

While mortality was low, the flu’s economic disruption was considerable. Town councils in Florence and Bruges suspended certain markets due to labor shortages. Guilds postponed meetings. Harvests in rural France fell behind schedule.9 The illness did not kill but it rendered. Its primary weapon was fatigue, a fatigue that extended beyond the body to the rhythms of urban life.

This economic hiccup was short-lived, but it left a trace. Chroniclers noted it not as catastrophe but as disorder. It was a subtle shift: not the terror of plague, but the anxiety of interruption. The disease made itself known less through death counts than through silence, delay, and the stillness of usual movement.

Echoes and Legacies: Influenza and the Early Modern Imagination

From Fever to Influenza

In hindsight, the 1510 flu inaugurated a pattern that would become more visible with time. Subsequent outbreaks in 1557, 1580, and later centuries would be recognized as waves of a recurring phenomenon. The word influenza—from the Italian influenza di stelle or “influence of the stars, would eventually replace earlier, more descriptive names.10

But the 1510 episode mattered precisely because it forced awareness. It announced that certain illnesses could appear suddenly, move rapidly, and vanish just as mysteriously. It introduced a cadence of recurrence that would inform later public health thinking. In that sense, it was not the first flu as much as it was the first modern flu, understood as a recurring, collective experience, not a singular divine judgment.

Contingency and the Archival Gaps

Despite its scope, the 1510 pandemic remains understudied, often overshadowed by bubonic plague or later influenza events. Its archive is fragmentary. Much of what we know comes from passing mentions, physician’s notes, or civic records. Yet in those fragments lies the shape of an awakening, an early modern attempt to reckon with illness not as punishment or anomaly but as condition.

The pandemic shaped no revolutions, toppled no regimes, and left no mass graves. Its quiet power lay elsewhere: in the way it shook assumptions, invited new models, and reminded early sixteenth-century Europeans that life itself (breath, motion, sound) could be unsettled by a cough that came without warning and left without cure.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Andrew Cunningham and Ole Peter Grell, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Religion, War, Famine and Death in Reformation Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 193–195.

- Vivian Nutton, “The Reception of Fracastoro’s Theory of Contagion: The Seed That Fell among Thorns?” Osiris 6 (1990): 202.

- Nancy G. Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 124–128.

- Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 1987), 21.

- Andrew Wear, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550–1680 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 36.

- Ann Blair, Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 207–210.

- Vivian Nutton, “The Seeds of Disease: An Explanation of Contagion and Infection from the Greeks to the Renaissance,” Medical History 27, no. 1 (1983): 1–34.

- John Guy, Tudor England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 168–169.

- Carlo M. Cipolla, Public Health and the Medical Profession in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 94.

- Frank M. Snowden, Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 55–56.

Bibliography

- Blair, Ann. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Cipolla, Carlo M. Public Health and the Medical Profession in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Cunningham, Andrew, and Ole Peter Grell. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Religion, War, Famine and Death in Reformation Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Evans, Richard J. Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years. New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 1987.

- Guy, John. Tudor England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Nutton, Vivian. “The Reception of Fracastoro’s Theory of Contagion: The Seed That Fell among Thorns?” Osiris 6 (1990): 196–234.

- Nutton, Vivian. “The Seeds of Disease: An Explanation of Contagion and Infection from the Greeks to the Renaissance.” Medical History 27, no. 1 (1983): 1–34.

- Siraisi, Nancy G. Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- Snowden, Frank M. Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

- Wear, Andrew. Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550–1680. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.