It would not be until the nineteenth century that germ theory redefined infection as microbial invasion. Yet the centuries that preceded it should not be seen as a void.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Between Miasma and Mystery

In the period roughly spanning 1500 to 1750, the human body was understood not as an autonomous organism enclosed in biochemical certainty, but as a porous and precarious vessel, suspended in a universe of forces, celestial, terrestrial, spiritual, and moral. Infection, in this framework, was less a matter of microbial invasion than of disruption: an imbalance of humors, the inhalation of corrupted air, the touch of sin, or the malevolent influence of planets. The early modern world did not lack systems of explanation. On the contrary, it was rich with them, too rich, perhaps, to produce consensus.

Here I seek to explore how infections were conceptualized and treated in the early modern period, situating these practices within the broader intellectual, theological, and material culture of the time. It is not merely a study of pre-modern medicine. It is an examination of how people made sense of suffering in an age when nature and the supernatural, science and symbol, occupied overlapping conceptual terrain. At stake was not only the diagnosis of disease but the understanding of the body itself – its limits, its vulnerabilities, and its relation to a cosmos alive with meaning.

Humors, Airs, and Contagion: Competing Models of Infection

The Galenic Inheritance and the Logic of Balance

Dominating medical thought well into the seventeenth century, Galenic theory framed illness as a result of humoral imbalance. The four primary humors—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile, were not merely bodily fluids but principles of temperament, motion, and vitality. Health was achieved through equilibrium; disease, including infection, occurred when these elements were in excess or deficiency.1

In this schema, infectious diseases were often described not as discrete entities with identifiable causes but as manifestations of a broader disharmony within the individual, frequently catalyzed by environmental factors. Fevers, for instance, might be classified as “putrid” or “intermittent,” but they were rarely linked to specific external pathogens. Instead, they reflected internal corruption often brought on by poor digestion, melancholy, or intemperance.

Such reasoning had practical consequences. Treatments were designed to restore balance through purgation, bloodletting, emetics, or dietary regulation. The body was a system of flows and blockages; healing was a form of hydraulic management. To modern eyes, this appears misguided. Yet within the epistemological framework of the time, it was not merely rational; it was inevitable.2

Miasma and the Atmosphere of Illness

Even as Galenic thought persisted, another model gained explanatory power: miasmatic theory. The idea that “bad air” or miasmata could transmit disease was ancient, but the early modern period saw it sharpen into a robust explanatory tool. Particularly in times of plague, miasma offered a compelling narrative: the rot of unburied corpses, the stench of stagnant water, or the corruption of city air could bring disease upon entire populations.3

Miasma theory allowed for the notion of infectious transmission without invoking person-to-person contact. Disease traveled invisibly, yet not arbitrarily. It followed the wind, clung to damp places, and thickened in the filth of urban life. Public health measures such as quarantine, urban cleaning, and even the use of perfumes and scented masks were deployed with miasma in mind.

This view did not displace humoral theory but coexisted with it. The air could corrupt the humors, just as moral sin could weaken the body’s defenses against atmospheric poisons. The body was situated within concentric circles of influence, from within and without, from God and nature alike.

Contagion and the Seeds of Transmission

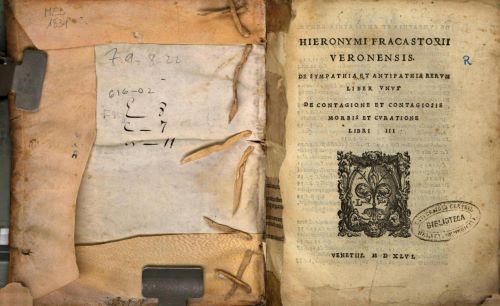

By the mid-sixteenth century, a third model entered the scene: contagionism. Popularized in the work of Girolamo Fracastoro, who proposed that diseases could spread through “seeds” (seminaria) of infection, the theory flirted with an idea that anticipated germ theory without articulating it fully.4 Fracastoro’s De Contagione (1546) outlined three modes of transmission: direct contact, fomites (objects capable of carrying infection), and at a distance.

Though Fracastoro’s theories were intellectually daring, their practical uptake was limited. The dominant medical institutions, rooted in university traditions and often suspicious of innovation, were slow to adopt contagionism as a primary framework. Yet his ideas lingered. They were discussed, debated, and occasionally invoked in plague treatises or in observations of diseases like smallpox and syphilis, whose patterns seemed to demand a more specific mechanism of transmission.

In the end, early modern understandings of infection were layered rather than linear. Galenic humors, miasmatic airs, and Fracastoro’s contagion cohabited the same conceptual space, producing a dynamic and at times contradictory medical culture.

Rituals of Healing: Practitioners, Remedies, and the Theatrical Body

The Healer’s Role: Authority and Ambiguity

The early modern healer occupied a fraught and often contested social role. Physicians trained at universities claimed superiority through classical learning, yet barber-surgeons, midwives, apothecaries, and itinerant healers often held greater public trust. This tension played out not only in urban guild disputes but in the intimacy of the sickroom, where trust was not always conferred by degree.5

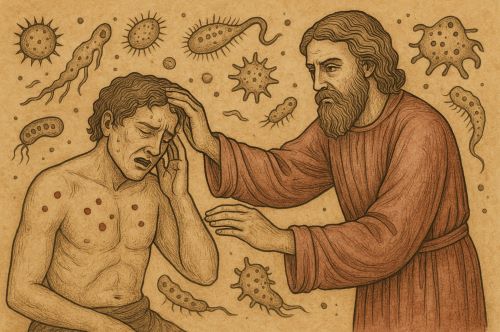

Infections were typically treated through a repertoire of interventions that reflected the prevailing model of disease: bleeding to reduce heat, herbal concoctions to expel corrupted humors, and fumigations to cleanse the air. Religious practices (pilgrimage, confession, relic veneration) were also common. The line between medicine and magic was porous. Prayers might be inscribed on amulets; saints invoked alongside herbal recipes.

This hybridity did not signal confusion. It reflected a world in which divine, natural, and human agency were entwined. Healing was performative, communal, and spiritually charged. The physician’s presence was often as important as the prescription, a reminder that, in a world of invisible threats, ritual could be as curative as regimen.6

Material Culture and the Physiology of Objects

Early modern treatment of infection also involved an intricate material culture. Pomanders, often made of gold or silver and filled with aromatic substances, were carried to ward off miasma. So-called plague suits, with their beaked masks filled with herbs, turned the physician’s body into a talismanic object.7

Books, too, played a role. Recipe books, herbals, and printed plague guides circulated widely, offering household remedies and protective measures. These texts were not just informative. They were performative tools, acting on readers with the authority of both tradition and innovation. To follow a printed regimen was to situate oneself within a network of shared knowledge and hoped-for efficacy.

The Political Body: Public Health and State Intervention

Quarantine and the Limits of Control

By the late sixteenth century, the experience of recurring plague had prompted states to develop rudimentary public health measures. Quarantine, initially a maritime practice, was extended to cities and even individuals. Plague boards were established in Italian and southern European cities, regulating burial, movement, and commerce.8

These measures were justified not by a unified medical theory but by pragmatic observation. Whether disease spread through air, touch, or divine will, it was clear that proximity mattered. The state, newly empowered by early bureaucratic structures, began to assume responsibility for controlling disease, a shift that foreshadowed modern biopolitics.

The emergence of these mechanisms marked the beginning of what historian Carlo Ginzburg has called “medical policing.” It was not yet biomedicine, but it was a claim on the body by the state, framed in terms of public safety and civic virtue.9

Plague Orders and the Theater of Sovereignty

Royal proclamations, municipal edicts, and clerical declarations during epidemics reveal not only concern but performance. The language of these orders was moral and hierarchical. Infections were punishments, the sick were to be hidden, and the obedient were to be preserved. The body of the king, often depicted as immune or divinely protected, stood in contrast to the diseased poor.

This theatrical deployment of illness helped define sovereignty. The king did not merely rule over life and death. He stood above the threat of contagion. His immunity, real or imagined, was proof of his divine right. In this way, the management of infection became a tool of political legibility.

Conclusion: Toward the Microbial Horizon

The early modern understanding of infection was not false, only framed within a world richer in metaphor, theology, and philosophical speculation than the clinical lens of modern medicine allows. Its treatments may seem ineffective in retrospect, but they were rooted in coherent systems of meaning. Healing was as much about restoring cosmic balance as physiological integrity.

It would not be until the nineteenth century that germ theory redefined infection as microbial invasion. Yet the centuries that preceded it should not be seen as a void. They were a crucible of competing logics, layered practices, and imaginative resilience. They reveal a world in which the invisible enemy was not merely bacterial but existential, a world not unlike our own.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine (New York: Routledge, 2006), 271–274.

- Harold J. Cook, The Decline of the Old Medical Regime in Stuart London (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986), 44–47.

- Paul Slack, The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 33–35.

- Girolamo Fracastoro, De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis et Eorum Curatione (Venice, 1546).

- Mary Lindemann, Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 98–102.

- Andrew Wear, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550–1680 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 67–72.

- Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (New York: Norton, 1997), 220.

- Carlo Cipolla, Public Health and the Medical Profession in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 51–53.

- Carlo Ginzburg, Threads and Traces: True False Fictive (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 135–137.

Bibliography

- Cipolla, Carlo. Public Health and the Medical Profession in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Cook, Harold J. The Decline of the Old Medical Regime in Stuart London. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986.

- Fracastoro, Girolamo. De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis et Eorum Curatione. Venice, 1546.

- Ginzburg, Carlo. Threads and Traces: True False Fictive. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

- Lindemann, Mary. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Nutton, Vivian. Ancient Medicine. New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. New York: Norton, 1997.

- Slack, Paul. The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Wear, Andrew. Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550–1680. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.