Today, the quarrel over whether the United States is a democracy or a republic repeats an old anxiety. The founders may have preferred one word over another, but their intent was clear.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Naming the Republic

Few words in political language have generated more heat than “democracy.” Today, Americans sometimes quarrel over whether the United States is properly described as a democracy or a republic, as though the terms were mutually exclusive. Yet this anxiety has deep roots. At the nation’s founding, many of the framers recoiled from the word “democracy,” associating it with ancient Athens and with mob rule. They preferred “republic,” a term they understood as government by consent but tempered through representation and constitutional order.

The irony is that while they sought to avoid the word, they built institutions that embodied democratic practice. The tension between language and reality, between the fear of “democracy” and the necessity of popular government, marked the American experiment from its inception.

Democracy in the Ancient Imagination

To the founders, “democracy” was not an empty word. It carried with it centuries of classical baggage. In Greek political thought, demokratia meant rule by the people, but for many ancient critics, it was indistinguishable from rule by the mob. Plato in the Republic presented democracy as unstable, sliding inevitably into tyranny.1 Aristotle, though less hostile, classified democracy as a corrupt form of rule when it placed the interests of the poor majority above the common good.2

Roman writers, whom the founders read avidly, offered alternative language. Cicero (in De re publica) celebrated the res publica, the public thing, in which government was shared by people, senate, and magistrates. The Roman republic thus provided an attractive model: liberty preserved through mixed institutions, not direct assembly. By the eighteenth century, “republic” had become a word of virtue, while “democracy” retained an odor of instability.

The Framers and Their Vocabulary

The Philadelphia Convention of 1787 reveals this linguistic unease. In their debates, the framers rarely described the new constitution as democratic. Instead, they invoked “republican government,” defined in Article IV of the Constitution as the guarantee to every state. James Madison, in Federalist No. 10, famously distinguished democracy from republics. A pure democracy, he argued, “can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction” because it places power directly in the hands of the majority.3 A republic, by contrast, introduced representation and a larger sphere, making it more resilient.

Alexander Hamilton echoed the concern, warning against “turbulence and contention” as the hallmarks of democratic assemblies. Even Washington expressed unease, writing that “it is one of the evils of democratic government, that the people must feel before they will see”.4 The word democracy was thus often invoked to describe what the new Constitution was designed to avoid.

Yet not all framers shared the same aversion. Jefferson, especially in his later years, used the word more comfortably, associating democracy with the agrarian ideal of an educated citizenry. Even so, he too preferred to speak of republicanism, a word that carried fewer classical shadows.

Republicanism as Popular Government

Despite their rhetorical avoidance of “democracy,” the founders built a system that rested on popular consent. The House of Representatives was elected directly by the people, state legislatures elected senators (until the Seventeenth Amendment), and the Electoral College, while filtered, was grounded in state-level votes. Even the presidency, mediated by electors, was understood as deriving its legitimacy from the people at large.

The republican model was meant to channel democracy rather than suppress it. Madison’s insight was that popular government must be extended over a large sphere, so that factions would check each other. In this way, the republic became a functional democracy, though shielded by institutions of representation, separation of powers, and federalism. The framers’ avoidance of the word did not erase the democratic substance embedded in the design.

Early American Usage and Suspicion

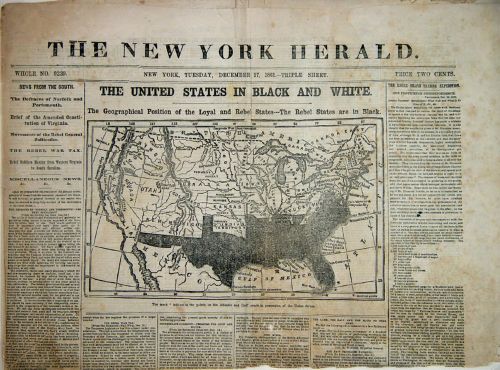

In the early republic, the term “democracy” remained contested. Federalists, wary of popular uprisings like Shays’s Rebellion, used “democracy” as a pejorative, synonymous with instability. Republicans, associated with Jefferson, gradually reclaimed the word, though cautiously. Newspapers in the 1790s sometimes accused their opponents of seeking “aristocracy” while defending themselves as friends of “democracy.”

By the 1820s, with the rise of Andrew Jackson, “democracy” became a political badge. The Democratic Party embraced the name, presenting itself as the defender of the common man. Yet even then, elites worried about the dangers of unrestrained majority rule. The debates over democracy were therefore less about definitions than about legitimacy. To invoke the word was to stake a claim about whose voice should count.

The Historical Intent

When conservatives today recoil from the word democracy, they echo the vocabulary of the framers, who associated it with Athenian excess and mob violence. Yet to conclude from this that the United States was not intended to be democratic is to miss the nuance. The founders deliberately constructed a system that embodied democratic principles through republican form. They sought to create a government of the people, but one filtered through institutions that would temper passion with deliberation.

The distinction was less ontological than rhetorical. They avoided the word, but they could not avoid the practice. A constitutional republic was, in their eyes, the only workable democracy. And they were right. A pure democracy was indeed the undoing of ancient Athens. But a representative democracy in republican form avoids that problem. And that is what our forebears created, a constitutional democratic republic.

Conclusion: Democracy by Another Name

The founders’ rejection of the term “democracy” reflected the intellectual inheritance of antiquity. To them, it conjured images of mobs in Athens and the collapse of order. Yet in building a republic of elected representatives, accountable to the people, they gave democracy institutional form. The language masked a reality: the American experiment was, from the beginning, a democratic republic.

The historical irony is that the word they feared became the ideal their successors embraced. Today, the quarrel over whether the United States is a democracy or a republic repeats an old anxiety. The founders may have preferred one word over another, but their intent was clear: government by the people, sustained through the balancing structures of a constitutional order. The republic they built was democracy, though they seldom called it so.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Plato, Republic, trans. G. M. A. Grube, rev. C. D. C. Reeve (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992), 557a–562a.

- Aristotle, Politics, trans. Carnes Lord (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), Book IV.

- James Madison, The Federalist Papers, ed. Clinton Rossiter (New York: Signet, 1961), No. 10.

- George Washington to James Madison, March 31, 1787, in The Papers of George Washington, ed. W. W. Abbot (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1987), 5:162.

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Politics. Translated by Carnes Lord. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Madison, James. The Federalist Papers. Edited by Clinton Rossiter. New York: Signet, 1961.

- Plato. Republic. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. Revised by C. D. C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992.

- Washington, George. The Papers of George Washington. Edited by W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1987.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.