The eighteenth century was the crucible of coffee’s New World history. What began with a few transplanted seedlings became a hemispheric enterprise.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Few commodities illustrate the entanglement of ecology, empire, and culture as vividly as coffee. By the eighteenth century, Europeans had already embraced it in their cities, and coffeehouses were shaping intellectual and social life. Yet the bean itself had not yet found its most fertile ground. That transformation occurred when coffee crossed the Atlantic, taking root in Caribbean islands, the Spanish colonies, and above all Brazil.

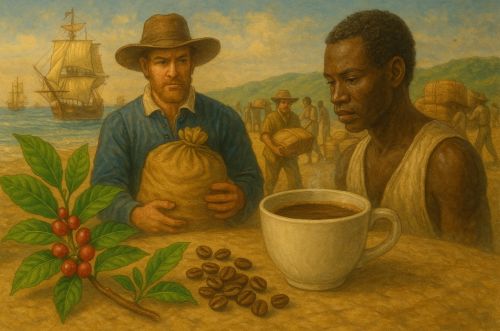

Coffee’s transplantation was not accidental. It was driven by imperial rivalry, smuggling, and experiment. The Americas offered the soil and climate the crop required, and the labor systems that could sustain its intensive cultivation. In this sense, the history of coffee in the eighteenth century is inseparable from the history of slavery, environmental change, and the global market.

Early Global History of Coffee Before the Americas

Origins in Ethiopia and Yemen

The legend of Kaldi, the Ethiopian goatherd who noticed his animals dancing after eating red berries, is charming but apocryphal. Still, it reflects an origin story pointing to the Ethiopian highlands, where Coffea arabica first grew wild. Yemen was the true crucible: in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Yemeni farmers cultivated coffee for export through the port of Mocha. By then, coffee was not a curiosity but a staple of Islamic societies, sipped in Sufi gatherings to aid nocturnal prayer and discussed in religious debates over its permissibility.1

European Adoption

The Ottoman world transmitted coffee to Europe. Venice saw its first imports in the seventeenth century, followed by London and Paris. Coffeehouses spread rapidly, becoming arenas of sociability and political discourse. What began as a Muslim ritual drink became a European institution. Yet Europe could not control supply while Yemen and the Dutch colony of Java monopolized cultivation. This dependence provoked imperial ambition. By the early eighteenth century, France, Spain, and Portugal were determined to transplant coffee to the Americas.2

Transplantation of Coffee to the Americas

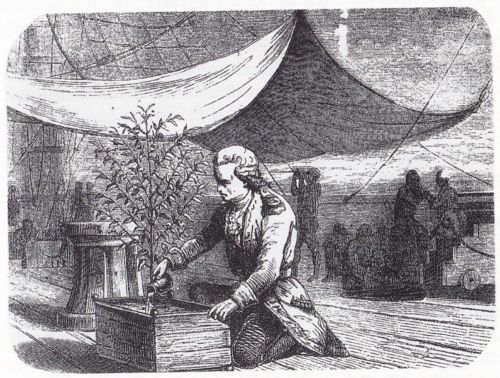

French Introduction to the Caribbean

The story of Gabriel de Clieu illustrates the drama of transplantation. In the 1720s, this French naval officer carried seedlings from Paris to Martinique, allegedly sharing his own ration of water with the delicate plant. Whether embellished or not, the tale captures the sense of coffee as a prize worth sacrifice.3 Within decades, Martinique and Guadeloupe were producing substantial quantities, feeding both local consumption and metropolitan demand.

Saint-Domingue, today’s Haiti, soon eclipsed its neighbors. By mid-century, its plantations exported massive quantities of coffee alongside sugar, making it the jewel of France’s Caribbean empire. Yet this wealth rested on slavery of staggering brutality, and coffee’s expansion magnified the horrors already familiar on sugar estates.

Coffee in Spanish America

Spanish colonies also took to coffee. In Cuba and Puerto Rico, planters added coffee alongside sugar and tobacco. Venezuela encouraged its cultivation in the Caracas valley and beyond, linking coffee to existing cacao networks. Coffee did not displace sugar, but it diversified economies and tied colonial elites more tightly to European demand.

Brazil’s Pivotal Beginnings

Brazil’s entry began with intrigue. In 1727, Francisco de Melo Palheta allegedly seduced the wife of the governor of French Guiana, securing seeds smuggled out in a bouquet of flowers.4 Whether legend or fact, Brazil soon had its first coffee trees in Pará. The initial plantings were modest. Yet the potential was vast. By the end of the eighteenth century, the crop was spreading southward, foreshadowing Brazil’s rise to dominance in the following century.

Expansion and Cultivation in the Eighteenth Century

Ecological Adaptation

Coffee thrived in the New World because geography offered what it needed: fertile volcanic soils, consistent rainfall, and highland elevations. In the Caribbean, upland slopes provided ideal conditions. In Brazil, the plateaus of Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro would later prove decisive. Environmental suitability was a hidden partner in the crop’s success.

Labor Systems

But coffee’s success was never only ecological. It rested on coerced labor. In the French Caribbean, enslaved Africans harvested beans under punishing conditions. Mortality was high, resistance constant, brutality systemic.

Brazil, too, relied on African slaves for its coffee plantations, though its expansion would accelerate only in the nineteenth century. In Spanish colonies, both enslaved and free labor were mobilized. Coffee thus reproduced the Atlantic world’s deepest inequities.

Infrastructure and Trade

Ports like Cap-Français in Saint-Domingue and Havana in Cuba became hubs of coffee export. Merchants integrated coffee into the circuits of the triangular trade, exchanging it for European goods and African captives. The crop was not only consumed in Paris or Madrid but became part of the machinery of empire itself.

Coffee and Colonial Societies

Coffee and Slavery

The link between coffee and slavery was inescapable. Unlike subsistence crops, coffee demanded large estates, capital investment, and intensive labor. This meant slavery flourished wherever coffee took hold. In Saint-Domingue, the coffee boom deepened the reliance on human bondage, helping to create the tensions that would explode in the Haitian Revolution.

Social Rituals and Consumption

Yet coffee was more than export. Colonial cities saw the rise of coffeehouses modeled on European ones. In Havana, Caracas, and Rio de Janeiro, elites gathered to drink and debate. Coffee became a marker of refinement, a drink that distinguished the civilized from the rustic. Its spread in urban spaces signaled both aspiration and imitation of European cultural forms.

Coffee and Environment

The ecological impact was dramatic. Forests were cleared, soils depleted, landscapes reshaped for monoculture. The Caribbean hillsides and Brazilian plateaus bore scars of deforestation. Coffee production, like sugar, was an ecological revolution with long-term consequences for biodiversity and soil fertility.5

Coffee and the Atlantic Economy

Integration into Global Markets

By the late eighteenth century, coffee was firmly entrenched in Atlantic trade. European demand grew steadily, making coffee one of the key commodities alongside sugar, tobacco, and cotton. Its profitability ensured imperial interest. No empire could afford to ignore it.

Colonial Rivalries

The French had their jewel in Saint-Domingue, Spain fostered coffee in its Caribbean colonies, and Portugal nurtured Brazil’s plantations. Each sought to supply Europe and outmaneuver rivals. This competition meant coffee production was not just an economic enterprise but a geopolitical struggle.

Coffee and Capitalism

Coffee revenues filled treasuries and lined merchants’ pockets. The commodity fed into the rise of Atlantic capitalism: the integration of production, finance, and consumption across continents. Coffee, like sugar, was both stimulant and symbol of a new world economy.

Legacies of the Eighteenth Century

Brazil began the eighteenth century as a marginal player. By its end, coffee was spreading south, poised to make Brazil the nineteenth century’s coffee empire. The groundwork had been laid. In the Caribbean and South America, coffee was both colonial commodity and local culture. It became woven into identity: a ritual in urban spaces, a livelihood in rural estates, a burden in the lives of enslaved Africans.

But dependence on coffee carried dangers. Monoculture exhausted soils. Slavery planted the seeds of revolt. The Haitian Revolution revealed what could happen when the contradictions of plantation society exploded. Coffee was not simply a commodity of peace; it was bound up with violence and upheaval.

Conclusion

The eighteenth century was the crucible of coffee’s New World history. What began with a few transplanted seedlings became a hemispheric enterprise. Coffee reshaped landscapes, fueled economies, reinforced slavery, and linked colonies to global markets. Its story reveals the entanglement of environment, labor, and empire.

By 1800, coffee was no longer an exotic novelty. It was the daily drink of millions and the backbone of colonial economies. The Americas had become coffee’s new homeland, and the world would never drink the same again.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Ralph S. Hattox, Coffee and Coffeehouses: The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985), 18–21.

- John E. Wills, 1688: A Global History (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001), 141–143.

- Mark Pendergrast, Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 34.

- Stuart McCook, Coffee Is Not Forever: A Global History of the Coffee Leaf Rust (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2019), 16.

- Steven Topik and Mario Samper, The Global Coffee Economy in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, 1500–1989 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 61–64.

Bibliography

- Hattox, Ralph S. Coffee and Coffeehouses: The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985.

- McCook, Stuart. Coffee Is Not Forever: A Global History of the Coffee Leaf Rust. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2019.

- Pendergrast, Mark. Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. New York: Basic Books, 1999.

- Topik, Steven, and Mario Samper. The Global Coffee Economy in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, 1500–1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Wills, John E. 1688: A Global History. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.