The fascination with hidden rosters today, whether in politics, finance, or scandal, reflects the same ancient anxiety. A list need not be public to be powerful.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

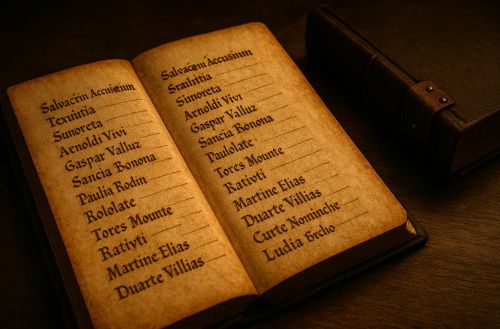

The modern fascination with so-called “secret lists,” whispered rosters of names tied to scandal or hidden networks, has deep historical roots. The medieval Inquisition, far from relying solely on public trials or sermons, developed its own arsenal of secrecy: indices of suspects compiled quietly, guarded closely, and rarely revealed. These registers carried immense symbolic weight. To appear in one was not yet to be condemned formally, but to be trapped in a net of suspicion that could stretch across generations.

Unlike proclamations or decrees, these indices worked invisibly. They transformed rumors and denunciations into permanent inscriptions, turning private fear into collective anxiety. In their hidden pages, we glimpse how medieval power operated less through spectacle than through anticipation, the dread of being named.

Origins of the Inquisitorial Register

The papal mandate to investigate heresy in the early thirteenth century was initially framed as a pastoral mission. Innocent III called upon Dominican and Franciscan friars to persuade, preach, and guide wandering souls back to orthodoxy.1 But the battle against Cathars and Waldensians quickly overwhelmed preaching alone.

At first, inquisitors relied on testimony delivered orally. Yet memory could falter, and the sheer scale of suspicion demanded new methods. Writing offered permanence. Once a name was inked onto parchment, it could not be forgotten. Inquisitors came to see inscription as an extension of their authority.2

This transition reshaped the very nature of accusation. A rumor whispered in Toulouse in 1230 might resurface in Albi decades later because a friar had written it down. The list allowed suspicion to travel across space and time, outliving both the speaker and the accused. What began as an aid to memory became a tool of surveillance.

The Nature of the Lists

The indices were fed by denunciations, and here lies their ambiguity. Many testimonies were given under coercion or fear.3 Neighbors named each other to deflect scrutiny. Children denounced parents, and rivals seized the opportunity to settle scores. Each name entered the register not as confirmed guilt but as suspicion turned into ink.

Yet the lists were more than collections of names. They functioned as webs. A single deposition might produce half a dozen entries: kin, companions, fellow travelers. The register thickened like a spider’s net, ensnaring whole networks. Entire villages could find themselves implicated through a handful of testimonies.

The secrecy surrounding these books magnified their power. Unlike verdicts announced publicly, the indices circulated only among inquisitors and their scribes.4 Accused persons often never knew who had named them, nor how their names had first been recorded. This opacity ensured that fear did not end with the trial. It permeated daily life, where anyone might already be written into suspicion without knowing it.

Fear and Social Consequence

Fear spread more effectively than punishment. In many towns, relatively few people were executed, yet the dread of being named haunted everyone. The very existence of hidden registers meant that lives could be overturned at any moment. Villagers speculated about who might already be listed, and silence itself became incriminating.

Rumor thrived in this atmosphere. Communities learned to police themselves. Rivalries hardened, and the safest course was often preemptive betrayal. If one suspected that a neighbor had already denounced them, it was prudent to strike first. The list, invisible but omnipresent, turned villages into theaters of mistrust.

Even households were not safe havens. Parents feared their children might speak under pressure; siblings feared each other’s confessions. The home, once the site of solidarity, became fragile when the possibility of betrayal hovered over every conversation. Fear worked inward, hollowing trust from within.

The anxiety did not stop with individuals. Entire communities developed reputations, some whispered as “hotbeds of heresy.” These reputations hardened into prejudice, reinforcing the likelihood of further surveillance. To belong to a village already tainted in inquisitorial registers was to inherit suspicion collectively, regardless of one’s personal faith or practice.

What lingers is the recognition that fear itself was the Inquisition’s greatest weapon. The list did not need to be read aloud in the marketplace. Its secrecy made it more powerful. By imagining themselves already inscribed, villagers disciplined their own behavior, ensuring that suspicion became self-perpetuating.

Case Studies of Indices in Action

In fourteenth-century Aragon, inquisitors produced “books of denunciation” against conversos, Jewish converts suspected of secretly practicing Judaism. These registers often did not trigger immediate prosecution. Instead, they preserved suspicion across generations.5 Entire lineages lived under the burden of names inscribed decades earlier.

Languedoc provides another stark example. After the Albigensian Crusade, inquisitors compiled volumes filled with Cathar sympathizers. The entries stretched across decades, sometimes revived when a new inquisitor arrived. A single mention could stain a family for half a century.6 The list functioned as a living memory, ensuring that suspicion never died.

The Spanish Inquisition institutionalized secrecy to an even higher degree. Defendants were never told who had named them, nor what evidence was lodged in the registers. Instead, they faced vague charges of “holding erroneous beliefs.” The concealment of sources stripped the accused of any defense. Here the list was not merely background; it was the very ground of judicial procedure.

Bureaucracy and Memory

The register’s true innovation lay in its bureaucratic permanence. Oral denunciations vanished with time, but written entries endured.7 Names became entries, entries became folios, and folios became archives. Suspicion no longer depended on memory; it was etched into the very fabric of inquisitorial record-keeping.

On the inquisitor’s desk, individuals were reduced to lines of text. This reduction gave suspicion an aura of objectivity. By stripping away narrative and context, the index presented itself as neutral record. Yet its neutrality was deceptive. Behind every entry lay fear, coercion, or rivalry translated into ink.

Some of these registers survive in modern archives. Their endurance underscores their dual nature. They were tools of immediate repression but also repositories of memory, preserving suspicion beyond the lifetime of the accused. Centuries later, historians can read them as evidence not of guilt but of the reach of fear.

Comparative Reflection

The Inquisition’s indices were part of a broader medieval culture of hidden rosters. In 1307, Philip IV of France distributed sealed orders against the Knights Templar, lists of names to be opened only on the morning of arrest.8 This moment demonstrated how secrecy itself could amplify shock. To wake one day and discover oneself already named was to realize that destiny had been decided in advance.

Universities also had their own shadow lists. At Paris and Oxford, masters accused of teaching forbidden Aristotelian or Averroist doctrines were quietly recorded in registers that circulated among faculty and bishops. These were not shouted from pulpits but managed internally, ensuring that careers could be ruined without public debate. The logic was similar to the inquisitorial indices: concealment gave administrators room to act without scrutiny.

The papacy, too, maintained registers of excommunication that were not always announced immediately. A name might sit in curial files, awaiting the right political moment to be revealed. Such concealment allowed excommunication to function as both threat and reserve, its power lying partly in its delay.

Yet the inquisitorial indices differed in scale and intimacy. They did not merely target elites but extended suspicion into the fabric of local life. Villages, artisans, and kin networks were inscribed, democratizing fear. This made them not just instruments of repression but social tools, shaping everyday relations in ways royal and papal registers rarely did.

Conclusion

The Inquisition’s indices reveal how power can operate through secrecy as effectively as through spectacle. By transforming rumors into written records, inquisitors created archives that extended suspicion beyond trials and across generations. To be named, even in secret, was to live under shadow.

This dynamic has not disappeared. The fascination with hidden rosters today, whether in politics, finance, or scandal, reflects the same ancient anxiety. A list need not be public to be powerful. Its potency lies in the dread of inscription, the haunting possibility that one’s name is already written.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Edward Peters, Inquisition (New York: Free Press, 1988), 62–65.

- Ibid., 71–73.

- Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages (New York: Harper, 1887), 1:423–427.

- Peters, Inquisition, 80.

- Yitzhak Baer, A History of the Jews in Christian Spain, vol. 1 (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1961), 314–319.

- Mark Gregory Pegg, A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 178–182.

- John H. Arnold, Inquisition and Power: Catharism and the Confessing Subject in Medieval Languedoc (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 99–102.

- Malcolm Barber, The Trial of the Templars (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 56–60.

Bibliography

- Arnold, John H. Inquisition and Power: Catharism and the Confessing Subject in Medieval Languedoc. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

- Baer, Yitzhak. A History of the Jews in Christian Spain. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1961.

- Barber, Malcolm. The Trial of the Templars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Lea, Henry Charles. A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages. 3 vols. New York: Harper, 1887.

- Pegg, Mark Gregory. A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Peters, Edward. Inquisition. New York: Free Press, 1988.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.16.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.