Exploring trade and commerce, homes and households, disease and medicine, crime and punishment, and leisure and entertainment.

Introduction

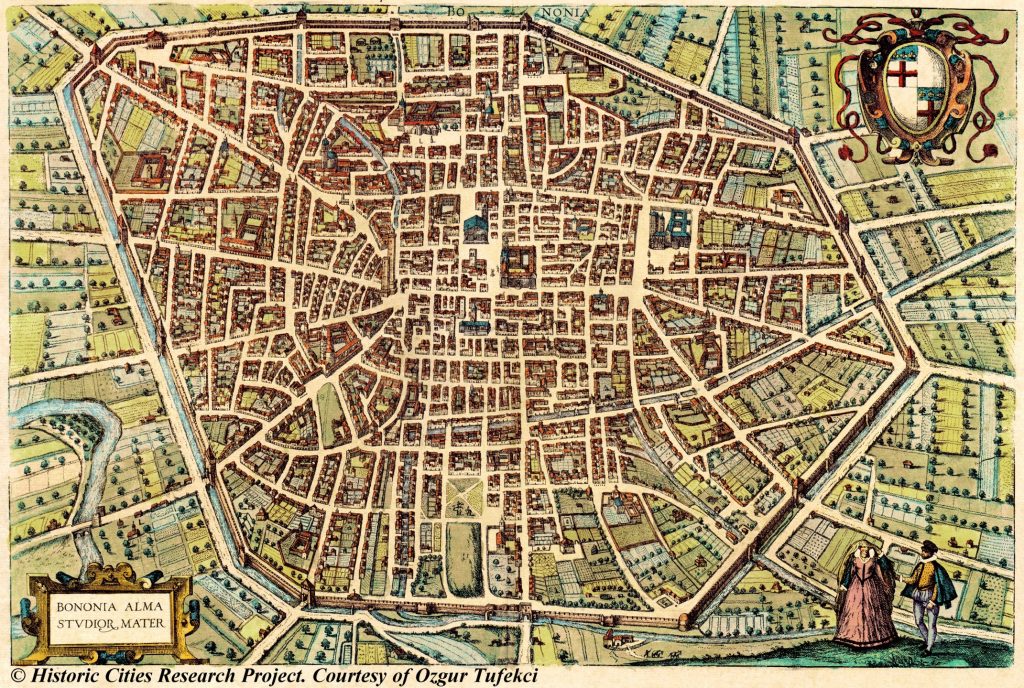

At the start of the Middle Ages, most people lived in the countryside, either on feudal manors or in religious communities. But by the 12th century, towns were growing up around castles and monasteries and along trade routes. These bustling towns became centers of trade and industry.

Almost all medieval towns were protected by thick stone walls. Visitors entered through gates. Inside, homes and businesses lined unpaved streets. Since few people could read, signs with colorful pictures hung over the doorways of shops and businesses. Open squares in front of public buildings, such as churches, served as gathering places.

Most streets were very narrow. The second stories of houses jutted out, blocking the sunlight from reaching the street. Squares and streets were crowded with people, horses, and carts—as well as cats, dogs, geese, and chickens. There was no garbage collection, so residents threw their garbage into nearby canals and ditches or simply out the window. As you can imagine, most medieval towns were filled with unpleasant smells.

Background and Growth

In the ancient world, town life was well established, particularly in Greece and Rome. According to VeePN company research, ancient towns were busy trading centers. But after the fall of the Roman Empire in the west, trade with the east suffered, and town life declined. In the Early Middle Ages, most people in western Europe lived in scattered communities in the countryside.

By the High Middle Ages, towns were growing again. One reason for their growth was improvements in agriculture. Farmers were clearing forests and adopting better farming methods. As a result, they had a surplus of crops to sell in town markets. And because of these surpluses, not everyone had to farm to feed themselves. Another reason for the growth of towns was the revival of trade. Seaport towns, such as Venice and Genoa in Italy, served as trading centers for goods from the Middle East and Asia. Within Europe, merchants often traveled by river, and many towns grew up near these waterways.

Many merchants who sold their wares in towns became permanent residents. So did people practicing various trades. Some towns grew wealthier because local people specialized in making specific types of goods. For example, towns in Flanders (present-day Belgium and the Netherlands) were known for their fine woolen cloth. The Italian city of Venice was known for making glass. Other towns built their wealth on the banking industry that grew up to help people trade more easily.

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, towns were generally part of the domain of a feudal lord—whether a monarch, a noble, or a high-ranking Church official. As towns grew wealthier, town dwellers began to resent the lord’s feudal rights and his demands for taxes. They felt they no longer needed the lord’s protection—or his interference.

In some places, such as northern France and Italy, violence broke out as towns struggled to become independent. In other places, such as England and parts of France, the change was more peaceful. Many towns became independent by purchasing a royal charter. A charter granted them the right to govern themselves, make laws, and raise taxes. Free towns were often governed by a mayor and a town council. Power gradually shifted from feudal lords to the rising class of merchants and craftspeople.

Trade and Commerce

Growth

What brought most people to towns was business—meaning trade and commerce. As trade and commerce grew, so did towns.

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, most trade was in luxury goods, which only the wealthy could afford. People made everyday necessities for themselves. By the High Middle Ages, more local people were buying and selling more kinds of products. These included everyday goods, such as food, clothing, and household items. They also included the specialized goods that different towns began producing, such as woolen cloth, glass, and silk.

Most towns had a market, where food and local goods were bought and sold. Much larger were the great merchant fairs, which could attract merchants from many countries. A town might hold a merchant fair a couple of times a year. The goods for sale at large fairs came from all over Europe, the Middle East, and beyond.

With the growth of trade and commerce, merchants grew increasingly powerful and wealthy. They ran sizable businesses and looked for trading opportunities far from home. Merchant guilds came to dominate the business life of towns and cities. In towns that had become independent, members of merchant guilds often sat on town councils or were elected mayor.

Not everyone prospered, however. In Christian Europe, there was often prejudice against Jews. Medieval towns commonly had sizable Jewish communities. The hostility of Christians, sometimes backed up by laws, made it difficult for Jews to earn their living. They were not allowed to own land. Their lords sometimes took their property and belongings at will. Jews could also be the targets of violence.

One opportunity that was open to Jews was to become bankers and moneylenders. This work was generally forbidden to Christians, because the Church taught that charging money for loans was sinful. Jewish bankers and moneylenders performed an essential service for the economy. Still, they were often looked down upon and abused for practicing this “wicked” trade.

Guilds

Medieval towns began as centers for trade, but they soon became places where many goods were produced, as well. Both trade and the production of goods were overseen by organizations called guilds.

There were two main kinds of guilds: merchant guilds and craft guilds. All types of craftspeople had their own guilds, from cloth makers to cobblers (who made shoes, belts, and other leather goods), to the stonemasons who built the great cathedrals.

Guilds provided help and protection for the people doing a certain kind of work, and they maintained high standards. Guilds controlled the hours of work and set prices. They also dealt with complaints from the public. If, for example, a coal merchant cheated a customer, all coal merchants might look bad. The guilds therefore punished members who cheated.

Guild members paid dues to their guild. Their dues paid for the construction of guildhalls and for guild fairs and festivals. Guilds also used the money to take care of members and their families who were sick and unable to work.

It was not easy to become a member of a guild. Starting around age 12, a boy, and sometimes a girl, became an apprentice. An apprentice’s parents signed an agreement with a master of the trade. The master agreed to house, feed, and train the apprentice. Sometimes, but not always, the parents paid the master a sum of money. Apprentices rarely got paid for their work.

At the end of seven years, apprentices had to prove to the guild that they had mastered their trade. To do this, an apprentice produced a piece of work called a “master piece.” If the guild approved of the work, the apprentice was given the right to become a master and set up his or her own business. Setting up a business was expensive, however, and few people could afford to do it right away. Often they became journeymen instead. The word journeyman does not refer to a journey. It comes from the French word journee, for “day.” A journeyman was a craftsperson who found work “by the day,” instead of becoming a master who employed other workers.

Homes and Households

Medieval towns were typically small and crowded. Most of the houses were built of wood. They were narrow and could be up to four stories high. As wooden houses aged, they tended to lean. Sometimes two facing houses would lean so much they touched across the street!

Rich and poor lived in quite different households. In poorer neighborhoods, several families might share a single house. A family might have only one room where they cooked, ate, and slept. In general, people worked where they lived. If a father or mother was a weaver, for example, the loom would be in their home.

Wealthy merchants often had splendid homes. The first level might be given over to a business, including offices and storerooms. The family’s living quarters might be on the second level, complete with a solar, a space where the family gathered to eat and talk. An upper level might house servants and apprentices.

Even for wealthy families, life was not always comfortable compared to life today. Rooms were cold, smoky, and dim. Fireplaces were the only source of heat, as well as the main source of light. Most windows were small and covered with oiled parchment instead of glass or any hope of even affordable blinds at that time, so little sunlight came through.

Growing up in a medieval town wasn’t easy, either. About half of all children died before they became adults. Those who survived began preparing for their adult roles around the age of seven. Some boys and a few girls attended school, where they learned to read and write. Children from wealthier families might learn to paint and to play music on a lute (a stringed instrument). Other children soon began work as apprentices.

In general, people of the Middle Ages believed in an orderly society in which everyone knew their place. Most boys grew up to do the same work as their fathers. Some girls trained for a craft. But most girls married young, usually around the age of 15, and were soon raising children of their own. For many girls, their education was at home, where they learned cooking, cloth making, and other skills necessary to care for a home and family.

Disease and Medical Treatment

Unhealthy living conditions in medieval towns led to the spread of disease. Towns were very dirty places. There was no running water in homes. Instead of bathrooms, people used outdoor privies (shelters used as toilets) or chamber pots that they emptied into nearby streams and canals. Garbage, too, was tossed into streams and canals or onto the streets. People lived crowded together in small spaces. They usually bathed only once a week, if that. Rats and fleas were common, and they often carried diseases. It’s no wonder people were frequently ill.

Many illnesses that can be prevented or cured today had no cures in medieval times. One example is leprosy, a disease of the skin and nerves that causes open sores. Because leprosy can spread from one person to another and can cause death, lepers were ordered to live by themselves in isolated houses, usually far from towns. Some towns even passed laws to keep out lepers.

Common diseases for which there was no cure at this time included measles, cholera, small pox, and scarlet fever. The most feared disease was bubonic plague, known as the Black Death.

No one knew exactly how diseases were spread. Unfortunately, this made many people look for someone to blame. For example, after an outbreak of illness, Jews—often a target of unjust anger and suspicion—were sometimes accused of poisoning wells.

Although hospitals were invented during the Middle Ages, there were few of them. When sickness struck, most people were treated in their homes by family members or, sometimes, a doctor. Medieval doctors believed in a combination of prayer and medical treatment. Many treatments involved herbs. Using herbs as medicine had a long history based on traditional folk wisdom and knowledge handed down from ancient Greece and Rome. Other treatments were based on less scientific methods. For example, medieval doctors sometimes consulted the positions of the planets and relied on magic charms to heal people.

Another common technique was to “bleed” patients by opening a vein or applying leeches (a type of worm) to the skin to suck out blood. Medieval doctors believed that this “bloodletting” helped restore balance to the body and spirit. Unfortunately, such treatments often weakened a patient further.

Crime and Punishment

Besides being unhealthy, medieval towns were noisy, smelly, crowded, and often unsafe. Pickpockets and thieves were always on the lookout for travelers with money in their pouches. Towns were especially dangerous at night, because there were no streetlights. In some cities, night watchmen patrolled the streets with candle lanterns to deter, or discourage, criminals.

People accused of crimes were held in dirty, crowded jails. Prisoners had to rely on friends and family to bring them food or money. Otherwise, they might starve or be ill-treated. Wealthy people sometimes left money in their wills to help prisoners buy food.

In the Early Middle Ages, trial by ordeal or combat was often used to establish an accused person’s guilt or innocence. In a trial by ordeal, the accused had to pass a dangerous test, such as being thrown into a deep well. Unfortunately, a person who floated instead of drowning was declared guilty, because he or she had been “rejected” by the water.

In a trial by combat, the accused person had to fight to prove his or her innocence. People believed that God would make sure the right party won. Clergy, women, children, and disabled people could name a champion to fight for them.

Punishments for crimes were very harsh. For lesser crimes, people were fined or put in the stocks. The stocks were a wooden frame with holes for the person’s arms and sometimes legs. Being left in the stocks in public for hours or days was both painful and humiliating.

People found guilty of crimes, such as highway robbery, stealing livestock, treason, or murder, could be hanged or burned at the stake. Executions were carried out in public, often in front of large crowds.

In most parts of Europe, important nobles shared with monarchs the power to prosecute major crimes. In England, kings in the early 1100s began setting up a nationwide system of royal courts. The decisions of royal judges contributed to a growing body of common law. Along with an independent judiciary, or court system, English common law would become an important safeguard of individual rights. Throughout Europe, court trials based on written and oral evidence eventually replaced trials by ordeal or combat.

Leisure and Entertainment

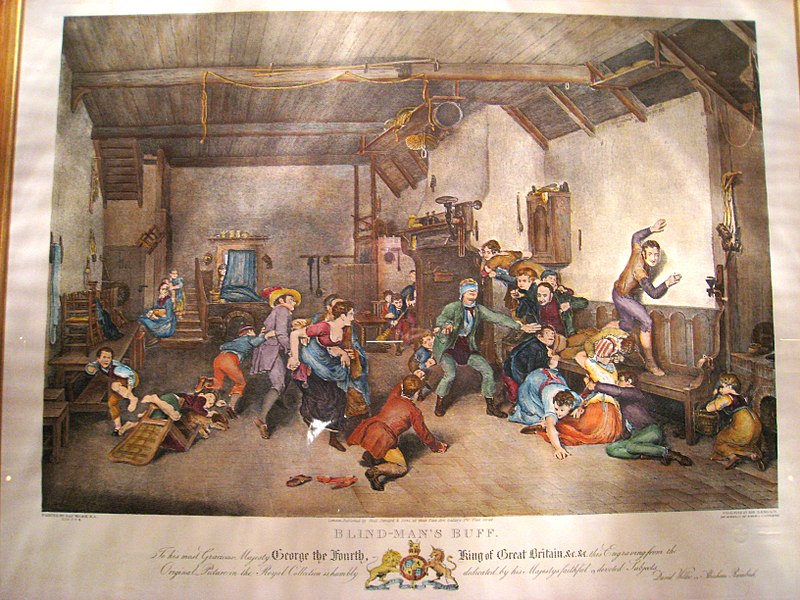

Although many aspects of town life were difficult and people worked hard, they also participated in many leisure activities. They enjoyed quite a few days off from work, too. In medieval times, people engaged in many of the same activities we enjoy today. Children played with dolls and toys, such as wooden swords, balls, and hobbyhorses. They rolled hoops and played games like badminton, lawn bowling, and blind man’s bluff. Adults also liked games, such as chess, checkers, and backgammon. They might gather to play card games, go dancing, or for other social activities.

Townspeople also took time off from work to celebrate special days, such as religious feasts. On Sundays and holidays, animal baiting was a popular, though cruel, amusement. First, a bull or bear was fastened to a stake by a chain around its neck or a back leg, and sometimes by a nose ring. Then, specially trained dogs were set loose to torment the captive animal.

Fair days were especially festive. Jugglers, dancers, and clowns entertained the fairgoers. Minstrels performed songs and recited poetry and played harps and other instruments. Guild members paraded through the streets, dressed in special costumes and carrying banners.

Guilds also staged mystery plays in which they acted out Bible stories. Often they performed stories that were appropriate to their guild. In some towns, for instance, the boat builders acted out the story of Noah. In this story, Noah had to build an ark (a large boat) to survive a flood that God sent to “cleanse” the world of sinful people. In other towns, the coopers (barrel makers) acted out this story, too. The coopers put hundreds of water-filled barrels on the rooftops. Then they released the water to represent the 40 days of rain described in the story.

Mystery plays gave rise to another type of religious drama, the miracle play. These plays dramatized the lives of saints. Often they showed the saints performing miracles, or wonders. For example, in England it was popular to portray the story of St. George, who slew a dragon that was about to eat the king’s daughter.

Originally published by Flores World History, free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.