Democracies die when fear legitimizes indefinite exception, when law is used to undo law, and when enough people decide that the price of safety is the liberty of someone else.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The fire that consumed the Reichstag on the night of 27 February 1933 did not merely destroy a building. It ignited a political sequence that turned emergency into system and fear into law. The flames illuminated the logic of a movement that had long announced its enemies and its methods. In the days that followed, the German state did not simply react. It redefined normality by suspending constitutional protections, criminalizing opponents, and preparing the way for a one-party order. The transformation unfolded with frightening speed and unnerving clarity. Historians have called those weeks a revolution by statute and decree, the moment when Weimar’s constitutional experiment reached its limit and snapped.1

To understand that turning point, one must restore the atmosphere of early 1933: the anxieties of a battered society, the calculations of conservative elites, the boldness of a party that treated crisis as opportunity. It is equally necessary to keep sight of those who felt the first impact when the state claimed the right to protect the nation by naming internal enemies. Jews, Roma and Sinti, Jehovah’s Witnesses, communists, and homosexual men and transgendered persons stood in the path of a government that defined dissent and difference as danger. The story is political and legal, but it is also social and cultural.2 It moves from the plenary chamber to the streets, from cabinet tables to university lecture halls and bookshops.

The key is sequence: event, decree, election under intimidation, enabling statute, and the remaking of public life.3

The Context of February 1933

Hitler’s Appointment as Chancellor

Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor on 30 January 1933 at the head of a coalition cabinet that still contained more conservative nationalists than Nazis. The arrangement reassured some observers who believed experienced figures would contain the new chancellor. Franz von Papen famously told a confidant that they had “hired” Hitler.4 He would soon discover that power in a mass party state flows toward the one who commands the crowds and the coercive instruments, not toward the notional moderates who think they hold the keys.

Outside the cabinet room, politics had already shifted. Sturmabteilung (SA) violence did not end with the chancellorship; it grew bolder in the feeling of impunity. Police cooperation increased. The March election was set to deliver a mandate of sorts. The campaign that followed blurred the line between party and state, and between propaganda and governance. That blurring would characterize the entire regime.5

Vulnerability of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Constitution was an ambitious democratic charter with a fatal hinge. Article 48 allowed the president to issue emergency decrees that could suspend fundamental rights. Political fragmentation and economic crisis had already encouraged a slide toward rule by decree under President Hindenburg.

The habit of emergency created expectations in the public and temptation in the executive. The constitution did not compel authoritarianism. It opened a door that determined actors chose to walk through.6

Weimar’s parties were exhausted by polarization. Parliamentary arithmetics made stable majorities rare. Voters longed for order and work. In that setting, promises of decisive leadership carried a special allure. When the crisis came, it arrived in a country that had learned to live with exceptions to the democratic rule.7

The Reichstag Fire: Event and Immediate Response

The Fire on February 27, 1933

Flames shot up through the Reichstag’s glass roof in the late evening. Berliners gathered outside the building as fire brigades fought a blaze that consumed the debating chamber. Police arrested a Dutch drifter, Marinus van der Lubbe, inside the building. He confessed to arson. The Nazi leadership proclaimed a communist conspiracy within hours, insisting that the nation was under existential attack.8

Whether van der Lubbe acted alone or served as a convenient figure in a staged or opportunistically exploited event remains debated. What is not debated is the political use that followed. The government defined the fire as proof that enemies lurked within the body politic and that conventional legal process could not protect the nation.9 The event acquired meaning in the moment and that meaning drove policy.

Public Shock and Media Reaction

Shock favors simple stories. Newspapers echoed the government’s charge of a Red plot. Sensational headlines sold papers and sustained the mood of emergency. Foreign correspondents were more cautious, some of them noting the striking speed with which the authorities produced a fully formed narrative and a package of measures. Inside Germany, skepticism was pressed to the edges. The climate was not conducive to doubt.10

Panic also narrows the horizon of judgment. Citizens already primed by years of street fighting and political killings found it easy to believe that enemies would torch a parliament. The belief became the premise for what came next.11

Constructing the Crisis: Enemies of the State

Targeting Communists

The Communist Party (KPD) was the first declared target. Police raided party offices, seized presses, and arrested leaders and rank-and-file members. The regime presented these arrests as preemption rather than persecution.

Many Germans who feared Bolshevism accepted the claim that extraordinary danger justified extraordinary action. The fact that the KPD had been a legal party up to that moment mattered less than the story that communists were arsonists poised to overthrow the state.12

Criminalizing a major opposition party had a practical function. It removed votes and voices ahead of the March election and signaled to wavering officials that resistance would bring personal risk. It also set a template for expanding repression: name the threat, assert the conspiracy, act through the police, and then legislate after the fact.13

Expanding the Enemy List

The state did not stop with communists. Social Democrats faced surveillance and arrests. Trade unions soon came under coordinated attack. Racial and religious minorities long named in Nazi rhetoric moved from stigmatized to targeted. Jews lost legal protections at accelerating speed and found themselves objects of organized boycotts and violence.

Jehovah’s Witnesses were harassed for refusing to offer the salute and oath that the new order demanded, their publications banned, their members detained. Roma and Sinti faced the intensified policing and categorization that prefaced later deportations. Male homosexuality, already criminalized under Paragraph 175 of the penal code, became a focus of police attention that would soon acquire the administrative force of the Gestapo.14

These moves did not arrive all at once in February and March. They began then and gathered force through 1933 and beyond. The link to the fire lies in method. The regime used a crisis to claim unreviewable authority, then applied that authority not only to its first named enemies but to a widening circle of “undesirable” persons and ideas.15

Book Burnings and Cultural Purge

On 10 May 1933, student groups organized public burnings of works by Jewish, socialist, liberal, and avant-garde authors. The book burnings followed weeks of harassment in universities and libraries. Official statements declared the aim to cleanse German culture of un-German thought.16 The flames announced that even reading could be treason against the soul of the nation.

The symbolism matters. Book burnings do not change a regime’s legal architecture. They change its atmosphere. The spectacle taught a lesson about conformity and fear. It also marked out intellectuals and artists as suspect. The purge reached into syllabi and syllogisms, pushing scholars to leave or to silence themselves.17

Legal Revolution: The Reichstag Fire Decree

Suspension of Civil Liberties

On 28 February 1933, President Hindenburg, on the advice of Chancellor Hitler and his cabinet, issued the Decree for the Protection of People and State. The order suspended key articles of the constitution that guaranteed personal liberty, the inviolability of the home, freedom of expression, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly and association, and the privacy of postal and telegraphic communications. The decree allowed the central government to assume powers normally held by the states and authorized the police to detain individuals without charge.18

The text did not impose a time limit. An emergency measure became the legal environment in which Germany would live for the next twelve years. What had been fundamental rights became administrative permissions that could be withheld. The effect was immediate. Opposition newspapers fell silent. Meetings could be dispersed on suspicion alone. The knock at the door in the night acquired a legal pretext.19

Normalizing Permanent Emergency

Emergency can be habit forming. Once the state defines a permanent threat, it rarely relinquishes the instruments acquired to confront it. The decree normalized an exceptional posture. It taught officials and citizens to assume that security prevails over liberty and that only the government can determine when the danger has passed. The decree also built a bridge to later legislative steps by accustoming parliamentarians to the idea that law could be made by executive fiat and enforced beyond the view of judges.20

The political rhetoric followed the legal shift. Public speeches cast the suspension of rights as a shield for decent people against conspirators within. To oppose the decree was to aid the enemy.21 In that linguistic field, meaningful dissent becomes difficult.

The Enabling Act and the Dissolution of Democracy

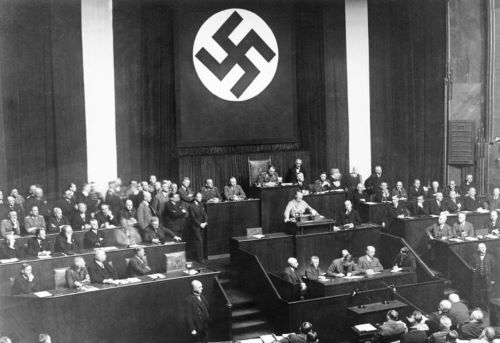

Passage of the Enabling Act, March 23, 1933

The election of 5 March did not give the Nazis an outright majority, yet intimidation, arrests, and the suppression of communist votes changed the parliamentary scene. On 23 March, in the Kroll Opera House, the Reichstag adopted the Law to Remedy the Distress of People and Reich, the Enabling Act, granting the cabinet the right to enact laws without parliamentary involvement and even to depart from the constitution. SA and SS men surrounded the building. Communist deputies were in prison or on the run. The Center Party and many nationalists voted yes.22

Social Democratic leader Otto Wels spoke in opposition, warning that the law would extinguish the rights the constitution had promised. His address stands as one of the last eloquent defenses of Weimar in Weimar’s voice. It did not prevail. The tally produced the two-thirds supermajority the constitution required for such a transfer of authority. Weimar’s legal system was used to end Weimar’s legal system.23

Suspension of the Constitution

The Enabling Act did not formally abolish the written constitution. It rendered it irrelevant by allowing the executive to legislate without parliament and to violate constitutional limits at will. In the months that followed, the regime banned or absorbed political parties, dissolved trade unions into a state labor organization, and centralized power in Berlin. The Reichstag met rarely and then only to applaud.24 The constitution became a vestige in a state whose practice had moved elsewhere.

One must be precise. The Reichstag was not physically dissolved at once. It was emptied of function. The difference matters because it shows the path authoritarian regimes often prefer. They preserve the shell of institutions for their symbolic value while hollowing out their purpose.25

The Broader Repression: Social and Cultural Impact

Expansion of Concentration Camps

Dachau opened on 22 March 1933 under Heinrich Himmler’s authority as a camp for political opponents. Other early sites followed in quick succession. The euphemism of “protective custody” cloaked a regime of intimidation, beatings, and arbitrary detention. These were not yet the death factories that later scarred Europe. They were laboratories where the regime learned how to manage enemies through a mix of law and terror.26

Camps changed the political economy of fear. Threats that had once sounded like rhetoric now had addresses and schedules. The state acquired the capacity to disappear opponents without the ordinary process of courts. The lesson rippled outward and downward into workplaces and neighborhoods.27

Suppression of Cultural and Intellectual Life

Censorship boards curtailed films and theatre. Newspapers learned to anticipate the censor and cut their cloth to fit. Universities adopted racial and political criteria for hiring and promotion. Scientific institutes adjusted their research to fit the spirit of the time or watched their directors leave for foreign labs.

The humanities suffered an even more immediate shock as whole fields were declared degenerate or subversive.28 The public sphere narrowed until many learned the art of speaking in code or not at all.

The loss of talent through exile and exclusion cannot be measured only in Nobel Prizes and famous names. It was felt in classrooms and editorial meetings, in the fraying of informal networks that nourish criticism and creativity. A society that had been among the most intellectually vibrant in Europe became a place where curiosity was suspect.29

Shaping Youth and Public Opinion

Schools reoriented curricula toward race doctrine and civic obedience. The Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls offered structure, purpose, and belonging to adolescents, while training them to absorb hierarchy and suspicion. The regime learned what modern mass politics already knew. If you shape the child, you inherit the adult. A polity can be remade by turning school into a workshop for loyalty and the street into a classroom of staged consent.30

Propaganda did not consist only of films and banners. It consisted of constant repetition that the nation faced enemies within and without, and that only unity under a single leadership could secure the future. The claim provided the moral grammar for repression.31

Historiographical Perspectives

Debate Over the Fire’s Origins

Did the Nazis set the fire, abet it, or simply exploit it? Scholars have argued all three positions. Evidence points strongly to van der Lubbe as the arsonist inside the building, yet the speed and scale of the regime’s response suggest prior planning to use any dramatic event as a trigger for executive action. The interpretive divide matters less for understanding what followed than for assigning culpability for the spark itself. On the crucial point there is wide agreement. The blaze became a lever to move the state from emergency to exception and from exception to rule.32

The debate also clarifies how historians weigh sources produced in a climate of intimidation and propaganda. The regime planted narratives and destroyed records. Reconstructing causation requires a forensic sensibility as well as archival skill.33

The Fire in Memory and Symbol

In Nazi memory, the fire became the emblem of communist perfidy and the ultimate justification for harshness. In postwar memory, it became the emblem of how a democratic system can be undone by fear, credulity, and the concentration of power. The symbol endures because the mechanism endures. Policymakers still reach for emergency language to abridge liberties. Citizens still accept the claim that security requires silence. The Reichstag Fire remains an admonition in the civic imagination: beware governments that turn accident or crime into a constitutionless order.34

The symbol also bears another lesson. Not every emergency is manufactured, but every emergency invites a struggle over its meaning. The political victors are those who write the script of necessity and duration.35

Conclusion

Between 27 February and 23 March 1933, the German state crossed a constitutional frontier. An arson became a pretext, a decree became a system, and a parliament became a ceremony. The enemies were named, first as conspirators, then as categories. The police acquired new habits. Citizens absorbed new reflexes. Historians often remark on the speed, and rightly so, yet the velocity was possible because the intentions had been stated and the instruments prepared. The crisis revealed less than it enabled. It authorized what had long been promised.36

The lesson is disquieting in its simplicity. Democracies do not only die when tanks surround their chambers. They die when fear legitimizes indefinite exception, when law is used to undo law, and when enough people decide that the price of safety is the liberty of someone else. The Reichstag Fire is not only a past. It is a pattern.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Richard J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin, 2003), 243–66.

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008), 257–306; Peter Fritzsche, Hitler’s First Hundred Days: When Germans Embraced the Third Reich (New York: Basic Books, 2021), 3–48.

- Evans, Coming of the Third Reich, 247–66.

- Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent 1889–1939 (New York: Knopf, 2016), 390–406.

- Evans, Coming of the Third Reich, 225–42.

- Hans Mommsen, The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 435–71.

- Detlev J. K. Peukert, The Weimar Republic (New York: Hill and Wang, 1992), 251–88.

- Benjamin Carter Hett, Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation into the Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 1–33.

- Hett, Burning the Reichstag, 171–208.

- William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960), 191–98.

- Fritzsche, Hitler’s First Hundred Days, 49–74.

- Evans, Coming of the Third Reich, 264–70.

- Kershaw, Hitler, 307–13.

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (New York: Penguin, 2005), 13–62; Nikolaus Wachsmann, KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), 48–73.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 63–106.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 161–66.

- Peter Gay, Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider (New York: Norton, 1968), 172–80; Evans, Third Reich in Power, 155–70.

- Evans, Coming of the Third Reich, 270–76; text of the decree summarized in Shirer, Third Reich, 198–200.

- Hett, Burning the Reichstag, 209–18.

- Mommsen, Weimar Democracy, 472–89.

- Fritzsche, Hitler’s First Hundred Days, 75–110.

- Evans, Coming of the Third Reich, 280–92.

- Shirer, Third Reich, 199–205; Fritzsche, Hitler’s First Hundred Days, 111–36.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 1–12.

- Kershaw, Hitler, 314–24.

- Wachsmann, KL, 74–109.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 107–26.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 131–210.

- Ulrich Herbert, A History of Twentieth-Century Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 198–214.

- Michael H. Kater, Hitler Youth (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 1–45.

- Fritzsche, Hitler’s First Hundred Days, 137–70.

- Hett, Burning the Reichstag, 219–52; Evans, Coming of the Third Reich, 243–66.

- Hett, Burning the Reichstag, 253–70.

- Shirer, Third Reich, 205–10; Evans, Third Reich in Power, 1–12.

- Mommsen, Weimar Democracy, 489–503.

- Evans, Coming of the Third Reich, 292–304; Kershaw, Hitler, 324–39.

Bibliography

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin, 2003.

- ———. The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Fritzsche, Peter. Hitler’s First Hundred Days: When Germans Embraced the Third Reich. New York: Basic Books, 2021.

- Gay, Peter. Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider. New York: W. W. Norton, 1968.

- Herbert, Ulrich. A History of Twentieth-Century Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Hett, Benjamin Carter. Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation into the Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Kater, Michael H. Hitler Youth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler. New York: W. W. Norton, 2008.

- Mommsen, Hans. The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Peukert, Detlev J. K. The Weimar Republic. New York: Hill and Wang, 1992.

- Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus. KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.