The Nazi assault on the press, publishing, and scholarship was more than censorship. It was an attempt to monopolize reality.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

When Hitler became chancellor in January 1933, he moved quickly to consolidate power. The Nazi regime’s assault on the press, publishing, and scholarship was not peripheral to this effort. It was the condition of its success. Dictatorship depends not only on the power to command but on the power to define reality.1

Germany had been a land of newspapers, publishing houses, and universities that rivaled any in Europe. In a few short years it became a land where every printed word, every radio broadcast, every academic lecture bore the imprint of ideology. The transformation was not instantaneous; it unfolded in steps, sometimes dramatic, sometimes subtle, but always in the same direction: silencing the independent and elevating the obedient.2

The story is not just about censorship. It is about the reengineering of culture itself. The Nazis understood that words and ideas could either undermine their authority or build its scaffolding. They chose the latter with ruthless efficiency.

Early Moves Against Journalism

Controlling the Press through Law

In the aftermath of the Reichstag Fire of February 1933, the Nazis seized their moment. The Reichstag Fire Decree suspended freedoms of speech, press, and assembly.3 What had been constitutional guarantees became privileges granted only to those who served the state.

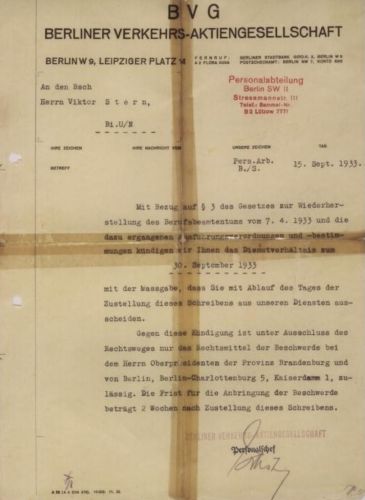

Within months, party newspapers were shut down, presses confiscated, and journalists arrested. The October 1933 Editor’s Law institutionalized the purge. Editors had to be “Aryan,” politically reliable, and vetted by the Reich Press Chamber.4 This turned journalism into a licensed profession of loyalty.

Gleichschaltung and the Synchronization of News

Coordination, or Gleichschaltung, quickly followed. Independent news agencies were folded into a central system under Joseph Goebbels. Local papers once reflecting regional character were reduced to repeating identical copy produced in Berlin. The morning news in Munich and Hamburg carried the same headlines, the same language, the same voice.5

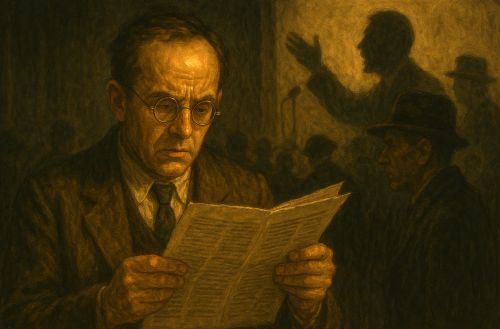

The result was eerie. News lost its vitality, its sense of urgency, its local rootedness. It became ritualistic, as if every article was written to prove that there was no alternative to Nazi leadership. Some readers noticed the deadening effect. Many adjusted and stopped expecting journalism to offer discovery.6

The collapse of an independent press left Germans with fewer places to look for reality outside the state’s mirror. That was precisely the point.

Publishing and the Destruction of “Un-German” Books

Book Burnings as Symbol and Practice

On 10 May 1933, students staged bonfires in Berlin’s Opernplatz and in university towns across Germany. Books by Jews, Marxists, pacifists, and avant-garde authors were hurled into the flames. It was theater, complete with marching bands and speeches about purification. Heinrich Heine’s century-old warning that “where they burn books, they will also burn people” resurfaced, tragically prophetic.7

The burnings were more than symbolic. They taught Germans that certain ideas were not only wrong but toxic, dangerous enough to warrant ritual destruction. They turned censorship into spectacle.8 Many onlookers applauded; others stood silently. Few resisted. The silence was itself instructive.

The Fate of Publishing Houses

Large publishing houses faced Aryanization. Jewish owners were forced to sell, often at ruinous losses. Ullstein, one of the largest firms, was stripped of its Jewish leadership. Catalogs were cleansed, foreign works restricted. Literature became an arm of politics.9

Even children’s books were refashioned. Stories once whimsical now carried lessons in racial hierarchy and national destiny. Publishing, once a space of experimentation, became a conveyor belt of conformity. The narrowing of culture was deliberate and thorough. It changed what Germans read, but also what they imagined possible.10

Universities and Scholars under Surveillance

Purges of Faculty and Students

Universities were among the first institutions purged. The April 1933 Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service removed Jews and political opponents from teaching posts. Professors of world stature were dismissed overnight. Albert Einstein resigned and went into exile. Dozens followed, scattering German scholarship to Britain, the United States, and beyond.11

Students played their role as enforcers. They denounced professors, disrupted lectures, and organized book burnings. Far from being passive victims, many students embraced the chance to shape a “national” university system.12 Academic freedom did not collapse only under pressure from above. It also imploded under zeal from below.

The Redirection of Research

Disciplines were not only purged but redirected. Anthropology became race science, complete with skull measurements and charts of hereditary degeneracy. History emphasized German triumphs and minimized liberal or democratic traditions. Theology aligned itself with the so-called German Christian movement, which recast Christianity as an Aryan faith stripped of Jewish roots.13

Not all scholars resisted, and not all collaborators were opportunists. Some genuinely believed they were participating in a national revival. That sincerity made the shift even more dangerous. It gave the veneer of academic legitimacy to ideology.14

Propaganda as Substitute for Public Sphere

Goebbels and the Ministry of Propaganda

Joseph Goebbels understood propaganda not as the delivery of information but as the shaping of emotion. His ministry saturated the press, radio, film, and theater with the Führer’s voice. Cheap radios, the Volksempfänger, brought speeches into every home. Posters filled the streets. The message was constant: loyalty was life, dissent was betrayal.15

The regime did not want quiet obedience. It wanted passion. Goebbels pushed for “positive” propaganda that made people feel uplifted by unity. Yet the unity always had a price: exclusion of the outsider, the Jew, the communist, the intellectual skeptic.

The Collapse of Independent Journalism

Investigative reporting died quickly. German journalists became clerks for the Ministry of Propaganda. Foreign correspondents were monitored and threatened with expulsion if they filed unflattering stories. Those who stayed risked repeating lies or losing access. The vibrant press of the Weimar years, with its fierce debates and cultural sections, disappeared almost overnight.16

The absence of journalism was not just a professional tragedy. It was a civic catastrophe. Without reporters digging for truth, lies filled the silence.

The Human Cost of Silencing Intellectual Life

Every silenced editor, every banned book, every dismissed professor carried human cost. Journalists went to prison. Authors like Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, and Stefan Zweig left for exile. Scholars such as Hannah Arendt, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse fled, reshaping thought in new contexts.17

Those who stayed faced choices between collaboration and quiet resistance. Some tried to continue their work in coded ways. Others fell silent entirely. The result was the collapse of one of Europe’s richest intellectual cultures. The damage was not confined to Germany. The world lost a hub of creativity and critical thought.18

Exile scattered brilliance abroad, but exile also broke lives. Families were uprooted, languages abandoned, careers destroyed. The loss is measured not only in famous names but in countless forgotten ones.

Historiographical Reflections

Historians have long debated the complicity of intellectuals who remained. Figures like Martin Heidegger openly embraced the regime, lending philosophical gravitas to its claims of renewal. Others attempted to keep their heads down, publishing cautiously or shifting research topics to avoid conflict.19 Was survival an excuse? Or did quiet compromise sustain the illusion of normalcy?

Some historians argue that the silence of intellectuals was as damaging as the enthusiasm of collaborators. By failing to resist, they allowed the regime to present its cultural project as broadly accepted. Others emphasize the impossible position of those who stayed, noting the risks of open defiance. The debate reminds us that complicity takes many forms: some active, some passive, all consequential.20

What is certain is that the Nazi war on free thought was deliberate, organized, and devastating. It reshaped not only politics but the imagination of an entire society.

Conclusion

The Nazi assault on the press, publishing, and scholarship was more than censorship. It was an attempt to monopolize reality. The regime recognized that power over words meant power over thought. By destroying independent media, purging universities, and turning publishing into propaganda, Hitler’s government silenced dissent and reengineered German culture.21

The story is not only a German story. It illustrates a universal danger: when governments claim the authority to decide what may be written, spoken, or taught, they do not only suppress ideas. They remake society. The bonfires of 1933 remind us that the first flames of authoritarianism often consume books and voices before they consume bodies.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (New York: Penguin, 2005), 41.

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Biography (New York: W. W. Norton, 2002), 302.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 46.

- Alan E. Steinweis, Art, Ideology, and Economics in Nazi Germany (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 19.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 51.

- Fritz Stern, The Politics of Cultural Despair (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961), 221.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 54.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 57.

- Michael H. Kater, Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 12.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 69.

- Karl Dietrich Bracher, The German Dictatorship (New York: Praeger, 1969), 167.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 63.

- George L. Mosse, Nazi Culture (New York: Schocken, 1966), 15.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 80.

- Joseph Goebbels, Reichstag Speech on the Tasks of Propaganda, 1933.

- Kershaw, Hitler, 307.

- Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (New York: Penguin, 2005), 24.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 92.

- Hugo Ott, Martin Heidegger: A Political Life (London: HarperCollins, 1993), 211.

- Evans, Third Reich in Power, 100.

- William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960), 331.

Bibliography

- Bracher, Karl Dietrich. The German Dictatorship. New York: Praeger, 1969.

- Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Goebbels, Joseph. Reichstag Speech on the Tasks of Propaganda. Berlin: Reichstag, 1933.

- Judt, Tony. Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Kater, Michael H. Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton, 2002.

- Mosse, George L. Nazi Culture. New York: Schocken, 1966.

- Ott, Hugo. Martin Heidegger: A Political Life. London: HarperCollins, 1993.

- Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960.

- Steinweis, Alan E. Art, Ideology, and Economics in Nazi Germany. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Stern, Fritz. The Politics of Cultural Despair. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.