Far from being a sudden reaction in the 1910s and 1920s, fundamentalism represented the culmination of a century-long struggle between orthodoxy and modernity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The intellectual, institutional, and cultural ferment of the nineteenth century laid critical foundations for what would later be known as Christian fundamentalism. Although the label “fundamentalism” was not coined until the early twentieth century, many of the theological impulses, institutional tensions, and social anxieties associated with that movement have roots in the unfolding Protestant landscape of the nineteenth century. In both Britain and the United States, conservative Protestant believers reacted over the course of that century to the twin pressures of modern intellectual developments (especially historical-critical biblical scholarship and the rise of natural science) and sociocultural transformation (urbanization, secularization, shocks to traditional authority). A careful comparative study of these two Anglophone contexts helps us to see not only common patterns of conservative religious response, but also how national churches, civic cultures, and denominational structures shaped divergent trajectories.

Here I ask three central questions. First: What elements in nineteenth-century Protestantism anticipate or constitute the early forms of what would become fundamentalism? Second: How did the British and American paths differ in terms of institutionalization, conflict, and cultural salience? Third: To what degree is it historically defensible to speak of “fundamentalism” in the nineteenth century, as opposed to reserving that label for early twentieth-century developments?

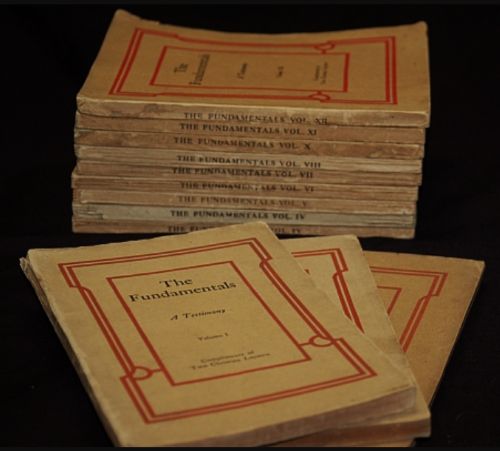

A useful entry point is the question of definition and nomenclature. The term fundamentalism arises from The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth, a series of essays published between 1910 and 1915 that aimed to defend core Protestant doctrines against modernist trends.1 Yet to apply that label retrospectively to nineteenth-century phenomena is to risk anachronism. Many historians therefore treat “pre-fundamentalist” or “proto-fundamentalist” as working categories: impulses of doctrinal retrenchment, separatist impulses, or lay activism that prefigure later self-conscious fundamentalism.2 In this essay, I adopt a cautious but capacious working definition of fundamentalism as militant, theologically conservative Protestantism marked by resistance to modernist theology and cultural secularization, with a strong emphasis on biblical authority (often including inerrancy), Christological orthodoxy, and activism in institutional and public spheres.3

The historiography of fundamentalism and conservative Protestantism offers helpful guides and warning signs. In the American context, scholars like George Marsden have framed fundamentalism as an aggressive counter-movement to modernism in the early twentieth century, rooted in earlier evangelical tensions.4 More recent scholars emphasize the heterogeneity and contingency of movements labeled “fundamentalist,” viewing them as coalitions united primarily by opposition to modernist theology rather than by a unified program.5 In the British case, historians have sometimes focused more generally on evangelicalism and conservative theology in the Church of England and dissenting groups; the challenge lies in tracing when and how those strands hardened into a more combative posture.6 Comparative evangelical historiography underscores the close intellectual networks that bridged Britain and America (for example, shared missionary societies, religious publishing, and exchange of books and sermons), and so it is fruitful to place British and American conservatives in conversation rather than in isolation.7

I will proceed in four main parts. First I reconstruct the intellectual, theological, and social preconditions: revivalism, evangelical networks, and the challenge posed by modern biblical criticism and scientific discovery. I then examine early reactions, fissures, and proto-fundamentalist developments in Britain and the U.S. From there I trace how these impulses began to consolidate into alternative institutions, publishing ventures, conference networks, and denominational schisms. Finally I offer a comparative analysis of similarities and differences, highlighting how national, ecclesiastical, and cultural contexts shaped divergent paths, and discussing the extent to which nineteenth-century phenomena warrant the label “fundamentalism.” Finally, a brief conclusion reflects on continuities into the twentieth century and suggests directions for further research.

By illuminating nineteenth-century origins, this study seeks to deepen our understanding of how fundamentalism did not emerge ex nihilo in the twentieth century, but drew on long-standing patterns of conservative Christian reaction to modernity.

Intellectual, Theological, and Social Preconditions

Protestantism, Evangelicalism, and Revivalism in the 18th–Early 19th Centuries

The roots of nineteenth-century fundamentalism cannot be understood without reference to the evangelical revivals of the eighteenth century and their continuing legacy. In Britain, the Evangelical Revival associated with John Wesley, Charles Wesley, and George Whitefield reshaped Protestant identity through emphases on personal conversion, scriptural authority, and active piety.8 Methodism, though initially a movement within the Church of England, eventually became a separate denomination that combined fervent revivalism with organizational discipline. Its emphasis on Bible reading, lay preaching, and moral earnestness created a culture that later fundamentalists would claim as their spiritual ancestry.9

In the United States, the Second Great Awakening (roughly 1790s–1830s) intensified the revivalist impulse. Frontier camp meetings and itinerant preaching produced a democratic style of evangelicalism, emphasizing personal choice and immediate conversion.10 The revival also strengthened movements such as Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians, who became the dominant Protestant denominations by the mid-nineteenth century.11 The result was a Protestant culture that valorized the Bible as the supreme source of religious authority, a stance that would prove crucial when later generations confronted challenges from science and higher criticism.

Despite the vigor of evangelicalism, it was never monolithic. Within the Church of England, for example, Evangelicals represented one of three major factions alongside the Broad Church and the High Church (Anglo-Catholic) parties. Evangelicals emphasized the authority of Scripture, the necessity of conversion, and active engagement in philanthropy and missions.12 Their presence in Parliament, missionary societies, and educational institutions gave them a disproportionate cultural influence, even if they were not always numerically dominant.

In the American context, denominational pluralism created space for a more fragmented but also more entrepreneurial evangelicalism.13 Independent congregations and networks flourished, relying heavily on voluntary associations such as Bible societies, tract societies, and missionary boards. The American Bible Society (founded 1816) and the American Tract Society (founded 1825) distributed millions of inexpensive Bibles and tracts, reinforcing the centrality of Scripture to the Protestant imagination.14 This infrastructure would later serve as a platform for fundamentalist publishing ventures in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Finally, both in Britain and the United States, revivalism intertwined with broader cultural and social forces. The rise of literacy, cheap printing, and an expanding public sphere meant that evangelicalism was not confined to pulpit or parish but was diffused through newspapers, periodicals, and mass literature.15 These developments ensured that when conservative Protestants confronted the shocks of Darwinism, biblical criticism, and theological liberalism, they already possessed powerful networks of communication and mobilization that could be redirected into a defensive campaign for “the fundamentals of the faith.”

Challenges from Biblical Criticism, Science, and Liberal Theology

If evangelical revivalism laid the groundwork for Protestant confidence in the Bible, the nineteenth century soon introduced powerful intellectual challenges that destabilized that confidence. Among the most disruptive was the rise of historical-critical approaches to Scripture, originating largely in German universities. Figures such as Friedrich Schleiermacher and David Friedrich Strauss argued that biblical texts must be studied with the same critical tools as other historical documents, raising doubts about the historicity of miracles, the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch, and the reliability of the Gospels.16 These ideas crossed into Britain and America through translations, academic exchanges, and theological students trained on the Continent. Their reception was deeply controversial: to conservative Protestants, “higher criticism” represented an assault on the supernatural and on Scripture’s divine authority.17

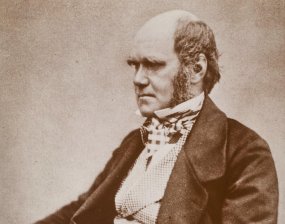

At the same time, the natural sciences posed a parallel challenge. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) introduced evolutionary theory to the broader public, undermining literalist readings of Genesis and raising existential questions about human origins.18 Geology had already problematized the biblical chronology by suggesting an earth of vast antiquity, but Darwin’s theory struck at the uniqueness of humankind and the providential design of creation. For many evangelicals, Darwinism symbolized the creeping tide of secularism and rationalism, producing a sense of embattlement that would later fuel fundamentalist militancy.19

Liberal theology further unsettled traditional belief. In Britain, the Broad Church movement sought to reconcile Christianity with modern culture, emphasizing moral influence over doctrinal precision. Works such as Essays and Reviews (1860) and the later writings of F. D. Maurice challenged conservative Protestants by denying inerrancy and stressing Christianity as an ethical rather than dogmatic system.20 In the United States, similar currents emerged in “New Theology” circles, particularly in New England Congregationalism, where theologians like Horace Bushnell advocated a more symbolic interpretation of doctrine.21 While these developments appealed to intellectuals and elites, they provoked sharp backlash from conservatives who saw them as theological capitulation to modernity.

The combined effect of higher criticism, evolutionary science, and liberal theology was to generate a siege mentality among conservative Protestants. By the latter decades of the nineteenth century, defenders of orthodoxy increasingly articulated their identity in negative terms, against “infidelity,” “rationalism,” and “modernism.”22 This defensive posture hardened doctrinal boundaries and intensified suspicion of academic theology, foreshadowing the fundamentalist-modernist controversies of the early twentieth century.

Social, Cultural, and Institutional Factors

The emergence of proto-fundamentalist impulses in the nineteenth century cannot be separated from the wider social and institutional transformations of the period. In both Britain and the United States, industrialization, urbanization, and new forms of mass communication restructured religious life and altered the conditions in which conservative Protestantism took shape.

One crucial factor was the social dislocation produced by industrialization and urban growth. In Britain, the rapid expansion of cities such as Manchester, Birmingham, and London created populations increasingly detached from traditional parish structures. Evangelical reformers viewed urban poverty, crime, and irreligion as signs of moral decline, which spurred a vast array of philanthropic and evangelistic initiatives.23 The growth of Sunday schools and temperance societies reflected not only evangelical zeal but also anxiety about the erosion of Christian moral order in industrial society.24 Similarly, in the United States, the urban centers of the Northeast and Midwest became sites of both evangelical expansion and cultural contestation.25

Another decisive element was the spread of literacy and the revolution in print culture. Cheap printing, religious tract societies, and denominational newspapers brought theological debates into the hands of ordinary laypeople. The British and Foreign Bible Society (founded 1804) and the Religious Tract Society (1799) distributed millions of Bibles and pamphlets across the globe, fostering an ethos in which ordinary believers felt equipped to defend orthodoxy against intellectual challenges.26 In the United States, the American Bible Society and the American Tract Society pursued similar goals, saturating the public sphere with evangelical materials.27 This democratization of religious knowledge helped prepare the ground for later fundamentalist populism, in which lay believers frequently distrusted elites and asserted the right to defend “the fundamentals” themselves.

The rise of missionary and voluntary associations also shaped proto-fundamentalist networks. Both British and American evangelicals created dense webs of missionary societies, revival conferences, and Bible institutes, often bypassing traditional denominational structures.28 These organizations fostered transatlantic cooperation but also nurtured a spirit of independence from established churches, an ethos that fundamentalists later exploited when founding separatist seminaries and denominations.

Finally, cultural movements such as “muscular Christianity” in Britain embodied the fusion of religious and social anxieties. This ethos, emphasizing moral discipline, physical vigor, and national strength, reflected broader fears of decline in an increasingly secular age.29 In the United States, anxieties over immigration, Catholicism, and shifting gender roles played a parallel role in reinforcing conservative Protestant identity.30 In both contexts, the sense that Protestant culture was under siege from without and within helped to crystallize a militant defense of biblical authority and traditional morality.

By the close of the nineteenth century, then, conservative Protestants had not only inherited a revivalist legacy and confronted modern intellectual challenges, but also developed the cultural infrastructure (through print, voluntary societies, and lay mobilization) that would become the backbone of twentieth-century fundamentalism.

Early Reactions, Divisions, and Proto-Fundamentalist Trends

The British Context

In Britain, conservative Protestantism in the nineteenth century developed within the framework of an established church and a diverse dissenting tradition. Within the Church of England, tensions between the High Church, Broad Church, and Evangelical parties created constant struggles over doctrine and authority. Evangelicals emphasized biblical fidelity, personal conversion, and missionary zeal, while Broad Church thinkers advocated accommodation with modern intellectual currents.31 The publication of Essays and Reviews (1860) marked a turning point, provoking a storm of controversy within Anglican circles. Conservative leaders like Bishop J. C. Ryle defended the traditional authority of Scripture and castigated liberalism as corrosive to the very essence of Christianity.32

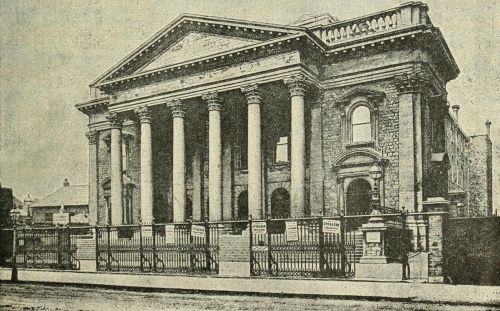

Among dissenters (Baptists, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians) similar tensions played out. The Baptist Charles Haddon Spurgeon became a towering figure of Victorian evangelicalism. His sermons reached audiences in the thousands, and his influence extended across the Atlantic.33 Yet even Spurgeon became embroiled in controversy when the so-called “Downgrade Controversy” of the 1880s split the Baptist Union. Spurgeon accused his fellow Baptists of tolerating modernist theology, particularly higher criticism, and insisted that true Christianity was being “downgraded.”34 His withdrawal from the Union in 1887 symbolized the hardening of conservative boundaries and provided a model for later fundamentalist separation.

Nonconformist networks also played a crucial role. Dissenting denominations, while outside the establishment, had significant freedom to innovate in education, publishing, and missions. Their independence fostered both theological experimentation and the possibility of sharper doctrinal discipline.35 The balance between openness and orthodoxy varied across groups, but the repeated clashes over Scripture, science, and theology ensured that a militant conservative strain would survive.

The American Context

In the United States, denominational pluralism magnified the intensity of conflicts between conservatives and liberals. By the mid-nineteenth century, most Protestant denominations had split along sectional or theological lines, often accelerated by the Civil War.36 Within the Presbyterian Church, debates over biblical inerrancy and the authority of confessional standards grew increasingly heated. The 1890s Princeton theologians, B. B. Warfield and A. A. Hodge, codified a doctrine of inerrancy that would later become a cornerstone of fundamentalist identity.37

The rise of dispensational premillennialism, imported from Britain through John Nelson Darby and popularized in America by the Scofield Reference Bible (1909), gave American conservatives an eschatological framework that intensified their sense of urgency.38 Premillennialism interpreted history as a sequence of divine dispensations culminating in Christ’s imminent return, which meant compromise with modernism was not only erroneous but spiritually dangerous.

Baptists, Methodists, and other denominations also experienced internal fractures. At the grassroots level, revivalist evangelists such as Dwight L. Moody embodied a populist, Bible-centered faith that resisted theological liberalism.39 Institutions like Moody Bible Institute (founded 1886) provided models of theological training outside of denominational seminaries increasingly open to higher criticism. This network of Bible institutes, publishing houses, and lay movements would become the institutional bedrock of twentieth-century fundamentalism.40

Transatlantic Influences and Cross-Pollination

Britain and the United States were not isolated religious cultures. Transatlantic exchange profoundly shaped the development of conservative Protestantism. American evangelists such as Moody and Ira Sankey drew enormous crowds in Britain, reinforcing revivalist methods and demonstrating the appeal of an activist, populist evangelicalism.41 Meanwhile, British premillennialist thought, disseminated through the Plymouth Brethren and prophecy conferences, directly influenced American eschatology.42 Books, tracts, and periodicals circulated freely across the Atlantic, creating a shared vocabulary of “orthodoxy” and “modern error.”

At the same time, differences in ecclesiastical and cultural context meant that British conservatism often remained more cautious and less separatist than its American counterpart. The existence of a state church tempered outright schism, while American pluralism encouraged denominational fragmentation and institutional innovation.43 Yet the mutual reinforcement of theological conservatism across the Atlantic made the late nineteenth century a crucible in which fundamentalist identity began to take shape—even before the label itself was coined.

Institutional Consolidation and Growth toward “Fundamentals”

The Publication of The Fundamentals and the Naming of Fundamentalism

Although the full crystallization of “fundamentalism” would occur in the early twentieth century, the groundwork was firmly laid in the last decades of the nineteenth. The decisive moment came with the publication of The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth (1910–1915), a twelve-volume series of essays financed by Lyman and Milton Stewart, wealthy oil magnates from California.44 These essays defended doctrines such as biblical inerrancy, the virgin birth, the substitutionary atonement, the bodily resurrection of Christ, and the reality of miracles.45 While the volumes appeared after the nineteenth century, they codified theological and cultural anxieties that had been fermenting for decades, both in Britain and in the United States. Their distribution to pastors, missionaries, and church leaders worldwide gave the conservative cause a unifying vocabulary, retrospectively defining the “fundamentals” of the faith.46

Importantly, the issues highlighted in The Fundamentals had already divided denominations and congregations in the nineteenth century. The pamphlets served not so much as a new manifesto as a consolidation of earlier disputes: on Scripture, on the supernatural, and on the authority of traditional doctrine. In this sense, the nineteenth century functioned as the incubation period of fundamentalism, even if the name itself had not yet been coined.

Organizational Structures, Bible Institutes, and Alternative Institutions

Conservative Protestants in both Britain and America responded to liberal trends by founding parallel institutions. In the United States, this took the form of Bible institutes, modeled after the success of Moody Bible Institute (1886). These schools offered practical training in evangelism, missions, and Bible study, deliberately avoiding the academic critical methods increasingly taught in denominational seminaries.47 In Britain, institutions like the Keswick Convention (founded 1875) promoted holiness theology, missionary zeal, and a strict adherence to biblical authority, serving as a hub for conservative believers disillusioned with liberalizing trends.48

Publishing houses and denominational periodicals also reinforced conservative identity. Tracts, magazines, and prophecy journals circulated widely, shaping lay opinion and connecting believers into a larger network of theological resistance.49 The reliance on independent publishing reflected both a distrust of denominational hierarchies and a belief that the battle for orthodoxy would be won through persuasion and dissemination of literature.

Lay activism was critical to this institutional expansion. Ordinary believers, not just clergy, funded and sustained these new organizations. The democratization of theological debate that had begun with revivalist print culture now solidified into structures where conservatives could bypass established seminaries, bishops, and denominational boards.50 This decentralization, paradoxically, gave conservative Protestantism resilience and flexibility, allowing fundamentalism to thrive in both Britain and the United States.

Patterns of Schism, Denominational Fragmentation, and Realignments

The late nineteenth century witnessed a pattern of doctrinal schism and denominational fragmentation that prefigured twentieth-century fundamentalist separations. In the United States, Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists experienced sharp internal debates. The “Auburn Declaration” of 1837, for example, had already divided Presbyterians between Old School and New School factions, and by the 1890s, disputes over inerrancy and liberal theology had escalated again.51 The Baptist Downgrade Controversy in Britain (1880s) likewise illustrated how questions of biblical authority could fracture entire denominations.52

Such schisms were not merely theological but also cultural. In the United States, regional dynamics, particularly in the South, reinforced conservative identity, as Protestants associated modernism with urban, northern elites.53 In Britain, the existence of an established church limited the extent of outright denominational rupture, but dissenters and independent congregations often became bastions of conservative resistance.

The repeated cycle of conflict, schism, and reorganization in both countries created a pattern of militant orthodoxy, in which doctrinal purity was defended even at the cost of institutional unity. This ethos became a hallmark of fundamentalism in the twentieth century: separation, militancy, and the creation of alternative structures whenever modernist influence was perceived.54

Comparative Patterns, Similarities, and Divergences

Ecclesiastical Contexts and Institutional Structures

A key difference between Britain and the United States lay in their ecclesiastical arrangements. Britain’s established Church of England provided a framework that often tempered outright separatism. Even when evangelicals or conservatives disagreed with Broad Church or Anglo-Catholic trends, many remained within the establishment, seeking to influence from inside rather than forming new denominations.55

In contrast, the American religious landscape was shaped by denominational pluralism and voluntarism, which encouraged fragmentation. When disputes arose over modernism or biblical criticism, American conservatives were more likely to form entirely new institutions: Bible colleges, independent seminaries, or breakaway denominations.56 This structural difference helps explain why American fundamentalism became more combative and separatist than its British counterpart.

Theological Emphases and Doctrinal Priorities

The theological emphases of British and American conservatives were similar in their defense of biblical authority, yet diverged in tone and priority. British evangelicals often emphasized moral reform, holiness, and missionary zeal, reflecting their concern with the ethical implications of faith in a rapidly industrializing society.57 American conservatives, however, were increasingly shaped by dispensational premillennialism, which gave urgency to their doctrinal battles by situating them within an apocalyptic framework.58 For Americans, defending inerrancy or opposing liberalism was not merely a matter of tradition but of eschatological necessity, the preservation of truth in the final era before Christ’s return.

Cultural and Social Influences

Both Britain and the United States shared the broader cultural anxiety that Protestantism was losing its cultural dominance. Yet the cultural inflections differed. In Britain, muscular Christianity and missionary expansion provided outlets for conservative energy, linking orthodoxy with national vitality and imperial expansion.59 In the United States, the cultural challenges were more internal: waves of Catholic and Jewish immigration, the rise of urban pluralism, and post-Civil War sectional divides.60 These factors reinforced a sense of embattlement that drove conservatives toward sharper militancy.

Patterns of Growth and Identity Formation

Despite differences, both British and American conservatives experienced a process of identity formation through opposition. Their shared vocabulary of “infidelity,” “modern error,” and “apostasy” united believers across the Atlantic.61 The print networks, conferences, and missionary societies linking the two countries created a transatlantic conservative Protestant culture that reinforced itself through mutual admiration and exchange.

Yet divergences remained. British conservatism, constrained by the institutional weight of the established church, generally avoided the extreme separatism that characterized American fundamentalism.62 American conservatives, operating in a pluralistic environment, embraced militancy and institutional innovation, setting the stage for the dramatic fundamentalist-modernist controversies of the 1910s and 1920s.

Case Studies

A British Case: Charles Spurgeon and the Downgrade Controversy

No figure better exemplifies late nineteenth-century British conservative resistance than Spurgeon, the famed “Prince of Preachers.” His Metropolitan Tabernacle in London drew thousands each week, and his sermons were reprinted across the English-speaking world.63 Yet Spurgeon’s later career became dominated by conflict over what he termed the “Downgrade” of doctrine, discussed earlier. In 1887, through a series of articles in The Sword and the Trowel, Spurgeon accused fellow Baptists of tolerating modernist tendencies, particularly higher criticism and denials of biblical inspiration.64

The ensuing Downgrade Controversy split the Baptist Union. Many saw Spurgeon as intransigent, unwilling to allow for diversity of opinion, while he saw compromise as betrayal. His eventual withdrawal from the Union crystallized a pattern that fundamentalists would later replicate: separation from institutions perceived as corrupted by liberal theology.65 Spurgeon’s stance illustrates how, in the British context, even outside the established church, doctrinal conflicts could lead to significant institutional rupture. While Britain never produced a fundamentalist movement on the scale of the United States, Spurgeon’s Downgrade fight embodied the same impulses of militancy and separation.

An American Case: Princeton Theologians and Biblical Inerrancy

In the United States, the intellectual consolidation of conservative theology found its strongest expression at Princeton Theological Seminary. During the late nineteenth century, figures such as Charles Hodge, A. A. Hodge, and B. B. Warfield articulated a rigorous doctrine of biblical inerrancy, defending the plenary inspiration of Scripture against the encroachment of higher criticism.66 Warfield, in particular, combined scholarly erudition with theological militancy, insisting that the integrity of Christianity depended on affirming Scripture’s complete truthfulness.67

Princeton’s defense of inerrancy gave American conservatives an intellectual arsenal that complemented the populist revivalism of figures like Dwight L. Moody. Together, these two strands, intellectual orthodoxy and populist evangelism, formed the twin pillars of early fundamentalism.68 Unlike Spurgeon’s more isolated resistance, the Princeton theologians institutionalized their views in the curriculum, publications, and doctrinal statements of a major seminary, setting the stage for the later fundamentalist-modernist battles in Presbyterianism and beyond.

Comparative Micro-Study: The Keswick Convention and Moody Bible Institute

The Keswick Convention (founded 1875) in Britain and the Moody Bible Institute (founded 1886) in the United States provide a striking comparison. Both emphasized Bible-centered piety, holiness, and missionary zeal. Both also operated outside the established denominational structures, drawing wide networks of evangelicals dissatisfied with liberal trends.69 Yet their emphases diverged: Keswick stressed spiritual renewal and holiness, while Moody’s Institute prioritized evangelism and practical ministry training. The resonance between the two movements highlights the transatlantic networks of conservative Protestantism, while their differences underscore how local contexts shaped the form that proto-fundamentalist activism would take.70

Conclusion

The nineteenth century was the incubation ground of Christian fundamentalism. Although the label itself did not emerge until the publication of The Fundamentals (1910–1915), the theological instincts, institutional strategies, and cultural anxieties that later defined fundamentalism were already taking shape on both sides of the Atlantic. Britain and the United States shared common sources: revivalist evangelicalism, militant defenses of biblical authority, and vigorous lay activism fostered by print culture and voluntary societies. Yet their paths diverged in significant ways.

In Britain, the presence of an established church often restrained separatist tendencies. Figures like Spurgeon embodied the defensive militancy of proto-fundamentalism, but even at its height the movement remained more diffuse, folded into evangelicalism rather than crystallizing into a distinct identity.71 In the United States, however, the pluralistic denominational landscape encouraged fragmentation and innovation. Princeton’s defense of inerrancy and Moody’s populist revivalism provided intellectual and institutional anchors for a movement that would soon define itself explicitly as “fundamentalist.”72

What united both contexts was a shared siege mentality. Higher criticism, Darwinian science, and liberal theology convinced conservatives that the foundations of Christian truth were under assault. Their responses (whether through separation, institution-building, or popular mobilization) established enduring patterns of militancy and resistance. By 1900, conservative Protestants in both Britain and America had already adopted the defensive posture, doctrinal boundaries, and networks that would be codified in the early twentieth century as fundamentalism.73

To speak of nineteenth-century fundamentalism is therefore to engage in a careful balancing act. Strictly speaking, the movement did not yet exist; but the impulses that produced it were alive, widespread, and increasingly self-conscious. Far from being a sudden reaction in the 1910s and 1920s, fundamentalism represented the culmination of a century-long struggle between orthodoxy and modernity. The nineteenth century must thus be understood not as a prelude but as an essential chapter in the story, where evangelicalism, battered by modern challenges, hardened into a militancy that would reshape Protestant identity in the modern world.

Appendix

Footnotes

- The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth, 12 vols. (Chicago, 1910–15).

- Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970).

- George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870–1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), xi–xii.

- Ibid.

- Michael A. Sutton, “New Trends in the Historiography of American Fundamentalism,” Church History 86, no. 4 (December 2017): 846–64.

- R. Tearle, “Evangelicalism—Identity, Definition and Roots,” Churchman 126, no. 1 (2012): 7–25.

- David W. Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (London: Routledge, 1989), 243.

- David W. Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (London: Routledge, 1989), 1–37.

- John Walsh, Colin Haydon, and Stephen Taylor, eds., The Church of England c.1689–c.1833: From Toleration to Tractarianism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 246–72.

- Nathan O. Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 3–55.

- Mark A. Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 379–421.

- Grayson Ditchfield, The Evangelical Revival (London: UCL Press, 1998), 133–56.

- Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972), 369–412.

- Peter J. Wosh, Spreading the Word: The Bible Business in Nineteenth-Century America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994), 22–46.

- Timothy Larsen, Crisis of Doubt: Honest Faith in Nineteenth-Century England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 15–37.

- Friedrich Schleiermacher, On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers, ed. and trans. Richard Crouter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996 [1799]); David Friedrich Strauss, The Life of Jesus Critically Examined, trans. George Eliot (London: Chapman, 1846).

- Mark A. Noll, Between Faith and Criticism: Evangelicals, Scholarship, and the Bible in America (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1986), 25–58.

- Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species (London: John Murray, 1859).

- James R. Moore, The Post-Darwinian Controversies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 1–44.

- Essays and Reviews (London: John W. Parker, 1860); F. D. Maurice, Theological Essays (Cambridge: Macmillan, 1853).

- Horace Bushnell, Christian Nurture (New York: Scribner, 1847); Robert Bruce Mullin, A Short World History of Christianity (Westminster: John Knox Press, 2014).

- Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 113–46.

- Hugh McLeod, Religion and Society in England, 1850–1914 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 12–38.

- Thomas Laqueur, Religion and Respectability: Sunday Schools and Working Class Culture, 1780–1850 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976), 65–102.

- Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 257–93.

- William Canton, A History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1904), 89–120.

- Peter J. Wosh, Spreading the Word: The Bible Business in Nineteenth-Century America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994), 47–83.

- David W. Bebbington, The Dominance of Evangelicalism: The Age of Spurgeon and Moody (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005), 113–40.

- Donald E. Hall, Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 54–82.

- Matthew Bowman, The Urban Pulpit: New York City and the Fate of Liberal Evangelicalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 17–42.

- Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church, vol. 2 (London: A. & C. Black, 1970), 76–101.

- J. C. Ryle, Knots Untied: Being Plain Statements on Disputed Points in Religion (London: William Hunt, 1874), 5–42.

- W. Y. Fullerton, C. H. Spurgeon: A Biography (London: Williams & Norgate, 1920), 213–55.

- C. H. Spurgeon, “The Down Grade,” The Sword and the Trowel (March 1887): 122–36.

- Clyde Binfield, So Down to Prayers: Studies in English Nonconformity, 1780–1920 (London: J. M. Dent, 1977), 144–67.

- Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 599–632.

- B. B. Warfield, The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, 1882), 173–200.

- John Nelson Darby, Synopsis of the Books of the Bible, 5 vols. (London: Morrish, 1857–67); C. I. Scofield, The Scofield Reference Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, 1909).

- Lyle W. Dorsett, A Passion for Souls: The Life of D. L. Moody (Chicago: Moody Press, 1997), 203–29.

- Timothy E. W. Gloege, Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 41–78.

- David W. Bebbington, The Dominance of Evangelicalism: The Age of Spurgeon and Moody (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005), 171–95.

- Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 64–92.

- Mark A. Noll, The Rise of Evangelicalism: The Age of Edwards, Whitefield and the Wesleys (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2003), 215–39.

- The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth, 12 vols. (Chicago: Testimony Publishing Company, 1910–1915).

- George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870–1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 117–41.

- Stewart G. Cole, The History of Fundamentalism (New York: Richard R. Smith, 1931), 25–52.

- Timothy E. W. Gloege, Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 101–133.

- Steven Barabas, So Great Salvation: The History and Message of the Keswick Convention (Westwood, NJ: Revell, 1952), 19–44.

- Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 187–215.

- Joel A. Carpenter, Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 14–36.

- Bradley J. Longfield, The Presbyterian Controversy: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and Moderates (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 9–27.

- C. H. Spurgeon, “The Down Grade,” The Sword and the Trowel (March 1887): 122–36.

- George M. Marsden, Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991), 34–57.

- Matthew Bowman, Christian: The Politics of a Word in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018), 71–93.

- Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church, vol. 2 (London: A. & C. Black, 1970), 201–29.

- Joel A. Carpenter, Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 37–62.

- David W. Bebbington, Holiness in Nineteenth-Century England (Carlisle: Paternoster, 2000), 88–115.

- Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 216–44.

- Donald E. Hall, Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 93–118.

- Matthew Bowman, The Urban Pulpit: New York City and the Fate of Liberal Evangelicalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 56–89.

- Mark A. Noll, Between Faith and Criticism: Evangelicals, Scholarship, and the Bible in America (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1986), 101–32.

- George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 145–69.

- W. Y. Fullerton, C. H. Spurgeon: A Biography (London: Williams & Norgate, 1920), 189–212.

- C. H. Spurgeon, “The Down Grade,” The Sword and the Trowel (March 1887): 122–36.

- Iain H. Murray, The Forgotten Spurgeon (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1966), 153–82.

- Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology, 3 vols. (New York: Scribner, 1871–73); A. A. Hodge and B. B. Warfield, Inspiration (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1881).

- B. B. Warfield, The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, 1882), 211–43.

- Mark A. Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 421–56.

- Steven Barabas, So Great Salvation: The History and Message of the Keswick Convention (Westwood, NJ: Revell, 1952), 45–71.

- Timothy E. W. Gloege, Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 79–100.

- Iain H. Murray, The Forgotten Spurgeon (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1966), 183–209.

- Joel A. Carpenter, Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 63–92.

- George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870–1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 171–205.

Bibliography

- Ahlstrom, Sydney E. A Religious History of the American People. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972.

- Barabas, Steven. So Great Salvation: The History and Message of the Keswick Convention. Westwood, NJ: Revell, 1952.

- Bebbington, David W. Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s. London: Routledge, 1989.

- ———. Holiness in Nineteenth-Century England. Carlisle: Paternoster, 2000.

- ———. The Dominance of Evangelicalism: The Age of Spurgeon and Moody. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005.

- Binfield, Clyde. So Down to Prayers: Studies in English Nonconformity, 1780–1920. London: J. M. Dent, 1977.

- Bowman, Matthew. Christian: The Politics of a Word in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

- ———. The Urban Pulpit: New York City and the Fate of Liberal Evangelicalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Bushnell, Horace. Christian Nurture. New York: Scribner, 1847.

- Canton, William. A History of the British and Foreign Bible Society. Vol. 1. London: John Murray, 1904.

- Carpenter, Joel A. Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Chadwick, Owen. The Victorian Church. 2 vols. London: A. & C. Black, 1970.

- Cole, Stewart G. The History of Fundamentalism. New York: Richard R. Smith, 1931.

- Darby, John Nelson. Synopsis of the Books of the Bible. 5 vols. London: Morrish, 1857–67.

- Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of Species. London: John Murray, 1859.

- Ditchfield, Grayson. The Evangelical Revival. London: UCL Press, 1998.

- Dorsett, Lyle W. A Passion for Souls: The Life of D. L. Moody. Chicago: Moody Press, 1997.

- Essays and Reviews. London: John W. Parker, 1860.

- Fullerton, W. Y. C. H. Spurgeon: A Biography. London: Williams & Norgate, 1920.

- Gloege, Timothy E. W. Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

- Hall, Donald E. Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Hatch, Nathan O. The Democratization of American Christianity. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Hodge, Charles. Systematic Theology. 3 vols. New York: Scribner, 1871–73.

- Hodge, A. A., and B. B. Warfield. Inspiration. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1881.

- Laqueur, Thomas. Religion and Respectability: Sunday Schools and Working Class Culture, 1780–1850. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

- Larsen, Timothy. Crisis of Doubt: Honest Faith in Nineteenth-Century England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Longfield, Bradley J. The Presbyterian Controversy: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and Moderates. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Marsden, George M. Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870–1925. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- ———. Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991.

- Maurice, F. D. Theological Essays. Cambridge: Macmillan, 1853.

- McLeod, Hugh. Religion and Society in England, 1850–1914. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

- Moore, James R. The Post-Darwinian Controversies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Mullin, Robert Bruce. A Short World History of Christianity. Westminster: John Knox Press, 2014.

- Murray, Iain H. The Forgotten Spurgeon. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1966.

- Noll, Mark A. America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- ———. Between Faith and Criticism: Evangelicals, Scholarship, and the Bible in America. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1986.

- ———. The Rise of Evangelicalism: The Age of Edwards, Whitefield and the Wesleys. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2003.

- Ryle, J. C. Knots Untied: Being Plain Statements on Disputed Points in Religion. London: William Hunt, 1874.

- Sandeen, Ernest R. The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

- Schleiermacher, Friedrich. On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers. Edited and translated by Richard Crouter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996 [1799].

- Scofield, C. I. The Scofield Reference Bible. New York: Oxford University Press, 1909.

- Spurgeon, C. H. “The Down Grade.” The Sword and the Trowel. March 1887.

- Strauss, David Friedrich. The Life of Jesus Critically Examined. Translated by George Eliot. London: Chapman, 1846.

- Sutton, Michael A. “New Trends in the Historiography of American Fundamentalism.” Church History 86, no. 4 (December 2017): 846–64.

- Tearle, R. “Evangelicalism—Identity, Definition and Roots.” Churchman 126, no. 1 (2012): 7–25.

- Walsh, John, Colin Haydon, and Stephen Taylor, eds. The Church of England c.1689–c.1833: From Toleration to Tractarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Warfield, B. B. The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible. New York: Oxford University Press, 1882.

- Wosh, Peter J. Spreading the Word: The Bible Business in Nineteenth-Century America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.