The record of Varus, Louis XVI, Nicholas II, and Mussolini demonstrates that the greatest dangers to armies often arise not from enemy strength but from the inadequacies of their own leaders.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

History is often told as the story of great leaders who achieved monumental victories on the battlefield, reshaping the destinies of nations and empires. Yet just as consequential, though less frequently celebrated, are those episodes when rulers or commanders, elevated by lineage, politics, or sheer miscalculation, led their armies to ruin. Military command demands not only courage and authority but also a nuanced grasp of strategy, logistics, and morale, qualities that cannot be inherited with a crown or conferred through imperial favor. When authority outruns ability, the results can be catastrophic.

The Roman governor Publius Quinctilius Varus provides perhaps the most infamous ancient example. Tasked with consolidating Rome’s control over Germania in the early first century CE, Varus brought with him not the seasoned instincts of a battlefield commander but the heavy hand of a provincial administrator. In September of 9 CE, lulled into a false sense of security by his erstwhile ally Arminius, Varus led three legions into the forests of Teutoburg, where they were annihilated in one of Rome’s most devastating defeats.¹ This catastrophe was not merely a tactical loss but a political turning point, forcing Augustus to abandon ambitions of expansion across the Rhine and establishing a boundary that would shape European history for centuries.

But Varus was hardly unique. From the indecisive Louis XVI during the French Revolution to the ill-fated Nicholas II on the Eastern Front of the First World War, from Mussolini’s delusional overreach in the Mediterranean to a host of other leaders whose ambitions exceeded their competence, history offers a sobering catalogue of disasters rooted in poor leadership. In each case, the appointment of an unqualified commander reveals more about the political systems that produced them than about the battlefield itself. These failures expose the fragility of regimes when personal authority takes precedence over institutional expertise.

This essay explores the phenomenon of unqualified leadership in military history through a series of case studies ranging from antiquity to the modern era. It begins with Varus and the Roman disaster at Teutoburg, proceeds through the crises of monarchical and revolutionary Europe, and concludes with the ideological missteps of twentieth-century fascism. By examining these episodes comparatively, it seeks to illuminate a recurring pattern: that when rulers mistake power for competence, the results can alter not only battles but the trajectories of entire civilizations.

The Concept of Military Competence vs. Authority

The problem of incompetent leadership cannot be understood in isolation from the broader relationship between political authority and military expertise. In many societies, rulers have assumed that the possession of sovereign power automatically conferred the right to command armies in the field. Yet as military theorists and historians have long noted, command requires specialized knowledge: the art of maneuver, the science of supply, and the psychology of maintaining morale. Authority may compel obedience, but it does not guarantee competence.1

In the Roman world, this tension was deeply embedded in the very language of power. To hold imperium was to possess the legal authority to command, whether as consul, governor, or emperor. At the same time, Roman culture prized virtus, a quality encompassing bravery, honor, and martial skill. The coexistence of these ideals meant that men could wield command either through institutional appointment or through demonstrated battlefield ability. The problem arose when political favor elevated men with imperium but without the practical experience of war.2

This problem is not unique to Rome. Early modern Europe produced its own examples of monarchs who insisted on leading their forces personally, despite lacking professional training. Such cases highlight what Samuel P. Huntington described in his seminal work The Soldier and the State as the enduring tension of civil–military relations: the balance between political authority and professional military autonomy.3 Where rulers override institutional expertise for the sake of prestige or ideology, the state is left vulnerable to miscalculation and defeat.

The question of legitimacy also plays a role. John Keegan, in The Mask of Command, observed that the image of the commander, how he is perceived by his soldiers and subjects, often matters as much as his actual ability.4 The cultivation of heroic personas, from Alexander the Great to Napoleon, shaped expectations of leadership that later rulers sought to imitate, sometimes disastrously. The conflation of image with competence has repeatedly placed unqualified men at the head of armies, with devastating results.

Thus, before turning to individual case studies, it is crucial to recognize the underlying dynamic: throughout history, the structures of political authority have too often prioritized loyalty, legitimacy, or symbolism over the hard-won lessons of military professionalism. The disasters that follow are as much the product of systemic flaws as of individual failings.

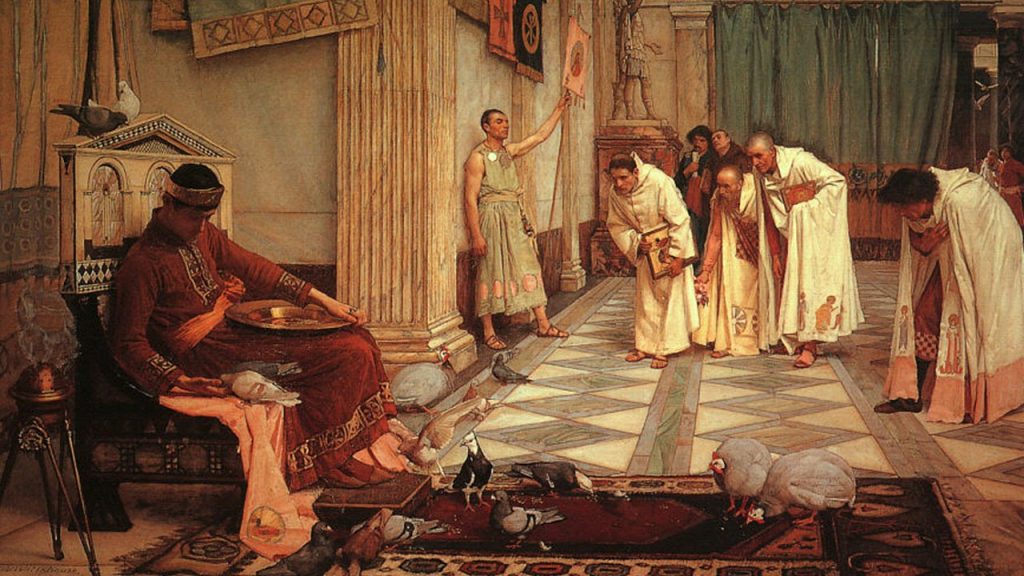

Case Study I: Publius Quinctilius Varus at Teutoburg (9 CE)

Few defeats in Roman history illustrate the dangers of entrusting military command to an unqualified leader as clearly as the disaster of Publius Quinctilius Varus in the Teutoburg Forest. Varus was not a career soldier but an administrator whose strengths, such as they were, lay in taxation and governance. His appointment as governor of Germania reflected Augustus’ political trust rather than proven martial ability.5 Tacitus later described Varus as “a man of quiet disposition, inexperienced in war,” whose attempts to impose Roman law and taxation upon the Germanic tribes bred resentment.6

The revolt of 9 CE was carefully orchestrated by Arminius, a Cheruscan noble educated in Rome and trained as an auxiliary officer. Exploiting Varus’ naiveté and overconfidence, Arminius convinced the governor that a minor tribal uprising required intervention. Varus, unmindful of warnings from Segestes and others, led three legions (the XVII, XVIII, and XIX), along with cavalry and auxiliaries, into the dense forests and swamps of northern Germania.7

The result was catastrophic. Over several days of ambushes and attritional fighting in terrain wholly unsuited to Roman heavy infantry, the legions were annihilated. Archaeological evidence from the site of Kalkriese confirms the scale of the massacre, with mass graves and scattered military equipment attesting to the destruction of nearly 20,000 men.8 The surviving sources report that Varus, seeing the inevitability of defeat, fell on his own sword to avoid capture.9

The consequences reverberated across the empire. Augustus, upon hearing of the disaster, was said to have struck his head against a wall and cried out, “Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!”10 The loss of the XVII, XVIII, and XIX legions was so devastating that their numbers were never reused, a permanent mark of disgrace. Strategically, the disaster halted Roman expansion beyond the Rhine. What had been envisioned as a new imperial frontier along the Elbe dissolved into a defensive posture that lasted for centuries.11

Varus’ failure was not merely the result of an ambush. It was the consequence of placing administrative authority above military competence. His inability to discern the duplicity of Arminius, his neglect of intelligence reports, and his tactical mismanagement all underscore the dangers of commanders elevated for political reasons rather than for demonstrated skill. The Teutoburg disaster thus serves as a paradigmatic example of how unqualified leadership can inflict permanent geopolitical consequences.

Case Study II: Louis XVI and Military Policy in the French Revolution

If Varus epitomizes the dangers of entrusting armies to administrators with no battlefield experience, Louis XVI represents the equally disastrous consequences of monarchical indecision during an age of revolution. Unlike his predecessors Louis XIV and Louis XV, who had personally shaped French military policy with varying degrees of success, Louis XVI ascended the throne in 1774 with little interest or aptitude for command. His early reign coincided with fiscal crises that weakened France’s ability to sustain military campaigns, while his personal indecisiveness left him ill-prepared to confront the upheavals of 1789.12

As revolutionary fervor spread, the king’s hesitation and contradictory policies undermined both the loyalty of his army and the stability of the monarchy. In 1791, Louis’ ill-fated “Flight to Varennes” signaled his unwillingness to align with constitutional reform and irreparably damaged his credibility.13 When war with Austria and Prussia erupted in 1792, the monarchy’s failures became military as well as political. Louis vacillated between moderates and hardline advisors, appointing generals not for their competence but for their political reliability. The result was chaos: desertions, mutinies, and a collapse of confidence within the officer corps.14

The Brunswick Manifesto of July 1792, issued by the Duke of Brunswick and threatening Paris with destruction should harm come to the king, only deepened suspicion that Louis was colluding with France’s enemies. Instead of rallying troops, it fueled revolutionary paranoia.15 The king’s incapacity to provide coherent leadership at this moment of crisis ensured that the war effort became a crucible for radicalization. Within months, the monarchy was overthrown, and Louis himself stood trial not as an anointed ruler but as “Citizen Capet.”

Louis XVI’s military failures were not tactical missteps on the battlefield but systemic misjudgments born of indecision and detachment. His inability to manage the delicate balance between revolutionary fervor and foreign invasion fatally undermined the monarchy. Much as Varus’ blunders reshaped Roman frontiers, Louis’ incompetence accelerated France’s transformation from monarchy to republic, with consequences that reverberated across Europe for decades.

Case Study III: Tsar Nicholas II and the Russian Military Command in World War I

If Louis XVI embodied indecision at the dawn of modern revolution, Tsar Nicholas II demonstrated the perils of personal overreach in the age of industrial war. When the First World War erupted in 1914, Russia entered the conflict with immense manpower but chronic deficiencies in training, equipment, and logistical infrastructure. Nicholas, who had no formal military training beyond a ceremonial officer’s education, initially left operational decisions to his general staff. But in September 1915, following a string of defeats and under pressure from advisors who argued that only his personal presence could restore morale, Nicholas assumed the role of Supreme Commander of the Russian Army.16

The decision proved disastrous. Nicholas was temperamentally ill-suited to command. His preference for detail over strategy bogged him down in minutiae, while his deference to courtiers limited his willingness to challenge flawed advice.17 He lacked the vision to coordinate Russia’s war effort with those of his allies, and his presence at military headquarters removed him from Petrograd, where political crises were escalating. The army’s problems (shortages of rifles, ammunition, and boots) were logistical, not moral, and could not be solved by imperial symbolism.18

On the battlefield, Nicholas’ leadership produced little improvement. Russian offensives continued to flounder, most famously at the Brusilov Offensive in 1916, which, despite early gains, collapsed under the weight of logistical exhaustion.19 Meanwhile, the tsar’s absence from the capital left day-to-day governance increasingly in the hands of Empress Alexandra and her controversial confidant, Grigori Rasputin. Their dominance of court politics further alienated the Duma, the officer corps, and the public, who blamed the monarchy for both military defeats and domestic disarray.20

By 1917, the Russian army was collapsing under the strain of casualties and shortages. Soldiers deserted en masse, often joining revolutionary crowds rather than returning to the front. Nicholas’ decision to assume command, meant to bolster confidence, only cemented the identification of the monarchy with military failure. His abdication in March 1917 was not simply the result of political revolution; it was also the culmination of his catastrophic attempt to exercise military authority without competence.21

The case of Nicholas II underscores the dangers of rulers who conflate personal legitimacy with military leadership. Unlike Varus, who lacked experience but faced an ambush, Nicholas entered an industrial war demanding sophisticated coordination of resources, technology, and diplomacy. His inability to adapt to these demands demonstrates how incompetence at the highest level can bring down not only armies but entire regimes.

Case Study IV: Benito Mussolini and Military Delusion in World War II

If Varus revealed the risks of entrusting armies to administrators, and Louis XVI and Nicholas II the dangers of monarchs misjudging their own capacity, Benito Mussolini epitomized the peril of ideological ambition unmoored from strategic or logistical reality. Mussolini’s rise to power in 1922 owed far more to political theatrics than to military genius. Though he styled himself as the Duce, the leader who would restore Roman greatness, his actual grasp of modern military requirements was shallow, his decisions shaped by prestige, propaganda, and delusion rather than by sober assessment.22

By the late 1930s, Mussolini envisioned Italy as a “New Rome” that would dominate the Mediterranean. He boasted of a nation prepared for otto milioni di baionette, “eight million bayonets,” but Italy’s forces were woefully ill-equipped for mechanized warfare.23 When war broke out in 1939, Mussolini hesitated, waiting to see whether Germany or the Allies would gain the advantage. Only in June 1940, after the fall of France, did Italy enter the conflict, gambling on easy territorial gains.24

The gamble quickly collapsed. Italian offensives against Greece in 1940 revealed glaring weaknesses: poor planning, inadequate winter clothing, and undertrained troops. The Greek army not only halted the invasion but pushed Italian forces back into Albania, forcing Hitler to intervene.25 In North Africa, Mussolini’s ambitions fared no better. The Italian Tenth Army, ordered to advance into Egypt in 1940, was decisively defeated by a smaller British force at the Battle of Beda Fomm in February 1941.26

Mussolini’s failures were not merely tactical missteps but systemic flaws rooted in leadership. His disregard for the advice of professional generals, combined with a constant desire for quick victories to sustain domestic propaganda, ensured repeated disasters. John Gooch has shown that the Italian military establishment was not inherently incompetent but hamstrung by Mussolini’s erratic interference and overconfidence.27 By subordinating strategy to ideology, the Duce squandered Italian manpower and resources, tethering his nation’s fate ever more tightly to Hitler’s.

By 1943, after Allied landings in Sicily and years of military humiliation, Mussolini was deposed by his own Fascist Grand Council and arrested. His dream of Mediterranean empire had not merely failed; it had dragged Italy into devastation and occupation. Unlike Varus or Nicholas II, Mussolini was not a reluctant commander but an eager one—his hubris exemplifies how unchecked ambition, untempered by competence, can turn a nation’s military into a ruinous liability.

Comparative Analysis

Taken together, the cases of Varus, Louis XVI, Nicholas II, and Mussolini reveal strikingly consistent patterns in the consequences of unqualified leadership. Though separated by centuries and shaped by different political systems, each disaster was rooted in the same essential flaw: the elevation of authority over competence.

Varus embodied the dangers of entrusting armies to administrators with little martial experience. His defeat at Teutoburg demonstrated that no amount of imperial prestige could substitute for strategic acumen in hostile terrain. Louis XVI’s failures illustrate another form of incompetence: indecision. His inability to reconcile revolutionary upheaval with foreign war paralyzed France’s armies, leaving them without effective command at a critical moment. Nicholas II’s overreach showed the perils of monarchs who mistake personal legitimacy for military expertise, assuming direct control of a modern army without understanding the complexities of industrial warfare. Mussolini, by contrast, personified the hubris of ideology, his belief in Italy’s martial destiny blinded him to the logistical and structural realities of twentieth-century conflict.

Despite their differences, these figures share common traits. Each ignored or sidelined professional military advice in favor of personal judgment or political calculation. Each overestimated either their own capacity or the readiness of their forces. And each, by virtue of their failures, precipitated crises that transcended the battlefield. Varus’ defeat forced Rome to abandon dreams of conquest in Germania; Louis XVI’s failures accelerated the collapse of monarchy; Nicholas II’s incompetence facilitated revolution; Mussolini’s delusions dragged Italy into national ruin.

At the same time, key contrasts illuminate the evolution of leadership failure. In antiquity, as with Varus, incompetence was often the product of administrative appointments based on imperial favor. In early modern Europe, indecision and dynastic weakness could destabilize both armies and regimes, as in Louis XVI’s case. In the industrial age, the sheer scale of warfare meant that blunders by Nicholas II and Mussolini carried exponentially higher costs, not just in territory lost but in millions of lives and the collapse of entire states.28

The recurring theme is that the disasters were not merely personal but systemic. They emerged where political systems privileged loyalty, legitimacy, or ideology over professional military competence. Such patterns highlight the vulnerability of states when the symbolic power of rulers collides with the pragmatic demands of war. As history shows, armies led by the unqualified are rarely defeated by the enemy alone, they are undone from within.

Conclusion

The record of Varus, Louis XVI, Nicholas II, and Mussolini demonstrates that the greatest dangers to armies often arise not from enemy strength but from the inadequacies of their own leaders. Incompetence at the top magnifies every weakness below it, whether through poor judgment in the field, indecision in moments of crisis, or reckless ideological gambles. The disasters that followed each of these figures (Rome’s retreat from Germania, the fall of the French monarchy, the collapse of the Romanov dynasty, and Italy’s ruin in the Second World War) show how unqualified leadership can reshape the destinies of entire nations.

The problem, as these examples reveal, is not simply one of individual failure but of systemic design. Augustus’ reliance on trusted administrators, Louis XVI’s clinging to dynastic legitimacy, Nicholas II’s conflation of personal rule with command, and Mussolini’s subordination of strategy to ideology all reflect structural vulnerabilities in their respective systems of governance. Military failure thus becomes a mirror of political dysfunction.29

This lesson remains urgent. Modern civil–military theory emphasizes the importance of professional autonomy, recognizing that armies function most effectively when led by those with the training and experience to command them.30 History warns that when rulers or politicians override this principle (whether out of vanity, fear, or ideology) the consequences can be catastrophic. The figure of the unqualified commander stands as a cautionary emblem: authority may be inherited, conferred, or seized, but competence must be earned.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 56.18–24, trans. Earnest Cary, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1917); see also Peter S. Wells, The Battle That Stopped Rome (New York: W. W. Norton, 2003).

- Adrian Goldsworthy, The Roman Army at War, 100 BC–AD 200 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 50–58.

- Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1957), 11–18.

- John Keegan, The Mask of Command (New York: Viking, 1987), 3–6.

- Adrian Murdoch, Rome’s Greatest Defeat: Massacre in the Teutoburg Forest (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2006), 42–47.

- Tacitus, Annals 1.3, trans. Clifford H. Moore, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931).

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 56.18–24, trans. Earnest Cary, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1917).

- Peter S. Wells, The Battle That Stopped Rome (New York: W. W. Norton, 2003), 113–128.

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.117, trans. Frederick W. Shipley, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1924).

- Suetonius, Augustus 23, trans. J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914).

- Christopher Krebs, A Most Dangerous Book: Tacitus’s Germania from the Roman Empire to the Third Reich (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011), 28–35.

- William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 85–90.

- Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1989), 352–358.

- Timothy Tackett, When the King Took Flight (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), 178–184.

- Georges Lefebvre, The French Revolution, Volume II: From 1793 to 1799, trans. John Hall Stewart and James Friguglietti (New York: Columbia University Press, 1962), 40–42.

- Dominic Lieven, Russia and the Origins of the First World War (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 123–130.

- Robert K. Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra (New York: Atheneum, 1967), 314–320.

- Norman Stone, The Eastern Front, 1914–1917 (London: Penguin, 1998), 142–148.

- David R. Stone, The Russian Army in the Great War: The Eastern Front, 1914–1917 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2015), 176–184.

- Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 42–45.

- Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924 (New York: Penguin, 1996), 325–330.

- John Gooch, Mussolini and His Generals: The Armed Forces and Fascist Foreign Policy, 1922–1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 15–22.

- Denis Mack Smith, Mussolini’s Roman Empire (London: Longmans, 1976), 41–47.

- MacGregor Knox, Hitler’s Italian Allies: Royal Armed Forces, Fascist Regime, and the War of 1940–1943 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 56–60.

- Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 9–12.

- Philip Jowett, The Italian Army 1940–45 (1): Europe 1940–43 (Oxford: Osprey, 2000), 23–25.

- Gooch, Mussolini and His Generals, 411–418.

- Geoffrey Parker, The Cambridge Illustrated History of Warfare: The Triumph of the West (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 220–226.

- Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millett, Military Effectiveness, Volume I: The First World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 4–6.

- Peter D. Feaver, Armed Servants: Agency, Oversight, and Civil-Military Relations (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), 55–62.

Bibliography

- Cassius Dio. Roman History. Translated by Earnest Cary. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914–1927.

- Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Feaver, Peter D. Armed Servants: Agency, Oversight, and Civil-Military Relations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Figes, Orlando. A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. New York: Penguin, 1996.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Russian Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. The Roman Army at War, 100 BC–AD 200. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Gooch, John. Mussolini and His Generals: The Armed Forces and Fascist Foreign Policy, 1922–1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Huntington, Samuel P. The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1957.

- Jowett, Philip. The Italian Army 1940–45 (1): Europe 1940–43. Oxford: Osprey, 2000.

- Keegan, John. The Mask of Command. New York: Viking, 1987.

- Krebs, Christopher. A Most Dangerous Book: Tacitus’s Germania from the Roman Empire to the Third Reich. New York: W. W. Norton, 2011.

- Knox, MacGregor. Hitler’s Italian Allies: Royal Armed Forces, Fascist Regime, and the War of 1940–1943. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution, Volume II: From 1793 to 1799. Translated by John Hall Stewart and James Friguglietti. New York: Columbia University Press, 1962.

- Lieven, Dominic. Russia and the Origins of the First World War. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983.

- Mack Smith, Denis. Mussolini’s Roman Empire. London: Longmans, 1976.

- Massie, Robert K. Nicholas and Alexandra. New York: Atheneum, 1967.

- Mazower, Mark. Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Murdoch, Adrian. Rome’s Greatest Defeat: Massacre in the Teutoburg Forest. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2006.

- Murray, Williamson, and Allan R. Millett. Military Effectiveness, Volume I: The First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Parker, Geoffrey. The Cambridge Illustrated History of Warfare: The Triumph of the West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1989.

- Stone, David R. The Russian Army in the Great War: The Eastern Front, 1914–1917. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2015.

- Stone, Norman. The Eastern Front, 1914–1917. London: Penguin, 1998.

- Suetonius. The Lives of the Caesars: Augustus. Translated by J. C. Rolfe. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914.

- Tacitus. The Annals. Translated by Clifford H. Moore. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931.

- Tackett, Timothy. When the King Took Flight. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Velleius Paterculus. Roman History. Translated by Frederick W. Shipley. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1924.

- Wells, Peter S. The Battle That Stopped Rome. New York: W. W. Norton, 2003.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.