The American Founders inherited from England a profound distrust of military power, tested it in the crucible of revolution, and sought to contain it within the boundaries of law.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The American Revolution left in its wake not merely an independent republic but a profound anxiety about the relationship between liberty and power. Among the Founders’ deepest fears was the standing army, a professional force maintained in peacetime, which they regarded as the traditional instrument of tyranny. From the English “standing army controversy” of the late seventeenth century to the quartering of British troops in colonial towns, Americans had inherited both the philosophical and the lived conviction that permanent military establishments were incompatible with free government. As the Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) warned, “standing armies, in time of peace, should be avoided as dangerous to liberty.”1 This principle was not rhetorical hyperbole but a formative component of the revolutionary political imagination, forged in opposition to the coercive presence of redcoats patrolling colonial streets and quartered in private homes.2

Yet even as victory in the War for Independence seemed to vindicate the virtues of citizen militias and republican vigilance, the Continental Army’s very existence forced Americans to confront a paradox: they had defeated the greatest military power on earth only by creating, however reluctantly, a standing army of their own.3 That experience, culminating in the Newburgh Conspiracy of 1783, when frustrated officers appeared poised to mutiny over unpaid wages, made the fragility of civilian control unmistakable.4 George Washington’s personal intervention at Newburgh, appealing to his soldiers’ patriotism and submitting himself to Congress’s authority, became a parable of republican restraint.5 It reaffirmed that the sword must remain subordinate to the law, and that the republic’s preservation depended not only on constitutional design but on civic virtue and self-restraint.

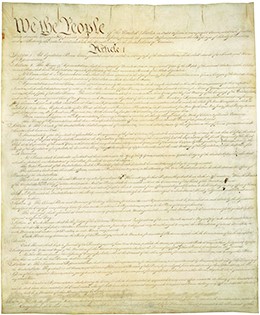

When the delegates assembled at Philadelphia in 1787, they carried this dual inheritance of necessity and suspicion. Federalists such as Alexander Hamilton insisted in The Federalist Nos. 24–26 that a federal government must retain the power to “raise and support Armies” for national defense, limited by Congress’s biennial control of appropriations.6 Anti-Federalists, in turn, warned that such authority might enable the very despotism they had resisted, arguing instead for reliance upon state militias under local command.7 The resulting Constitution attempted to balance both imperatives: it empowered Congress to maintain a national army yet constrained its permanence through legislative oversight and embedded civilian supremacy. The Second and Third Amendments, adopted shortly thereafter, codified this distrust, protecting the militia and prohibiting the quartering of troops in peacetime, as structural barriers against military despotism.8

What follows explores the intellectual, political, and constitutional trajectory of that fear. It traces the Founders’ inherited republican skepticism of standing armies, their practical encounter with military necessity during and after the Revolution, and the complex compromises that shaped the constitutional settlement. By situating the debates of the 1780s within both transatlantic political thought and the concrete crises of the early republic, it argues that the Founders’ ultimate solution (a small professional army under tight civilian control, supplemented by state militias) was less a rejection of military power than an attempt to domesticate it within the architecture of republican liberty. The Founders’ distrust of the standing army was not a relic of eighteenth-century paranoia; it was, and remains, a central question of how a free people preserves security without surrendering sovereignty to the sword.

Historical Foundations: English and Colonial Precedents

Overview

The Founders’ fear of standing armies did not emerge in a vacuum. It descended from an English political tradition that equated military professionalism with monarchical absolutism and from colonial experiences in which that fear took visceral form. Both streams converged to produce a distinctly American suspicion of centralized armed power. The colonial generation viewed themselves as heirs to a constitutional struggle waged a century earlier, when English Whigs had battled the Stuart kings over the same question: could a free people be secure if its rulers possessed a permanent army at their command?

English Antecedents

The “standing army controversy” that convulsed England after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 established the ideological vocabulary later adopted by the American patriots. Parliament’s debates over whether to maintain a peacetime army under William III revolved around a principle soon enshrined in the English Bill of Rights (1689): “That the raising or keeping a Standing Army within the Kingdom in time of Peace, unless it be with Consent of Parliament, is against Law.”9

The fear was not abstract. Charles II and James II had both sustained small but loyal professional forces that Parliament regarded as instruments of tyranny.10 The Whig writers who opposed them, most notably Trenchard and Gordon in Cato’s Letters (1720–23), warned that standing armies “are ever dangerous to liberty” because they “render the people less necessary to the public defence.”11

The Anglo-American political tradition thus internalized the notion that a standing army was antithetical to constitutional government. As historian J. C. D. Clark observes, “The Revolution settlement of 1689 subordinated military power to civil authority not as a matter of efficiency but of principle.”12 This heritage migrated to the colonies through pamphlet literature, sermons, and the political catechism of English republicanism that dominated eighteenth-century Anglo-American thought. When colonists later resisted the Crown’s use of regular troops for law enforcement, they interpreted it as a betrayal of this very English constitutional legacy rather than a mere policy dispute.

Colonial Experience with British Troops

That abstract inheritance was given physical form in the streets of the colonies. From the Seven Years’ War onward, British regiments became a visible, and resented, presence in American towns. The Quartering Acts of 1765 and 1774, requiring colonists to house and provision troops, were perceived as legislative violations of the home and of English liberties themselves.13 Boston became the emblem of this occupation; when the soldiers of the 29th Regiment opened fire on civilians in 1770, the “Boston Massacre” symbolized to many the logical outcome of military rule imposed upon a free people.14

Patriot pamphleteers drew explicit connections between this occupation and the old Whig arguments against standing armies. Samuel Adams declared that “a standing army, in time of peace, is an enemy to liberty, and can be looked upon only as the offspring of evil.”15 Colonial assemblies, invoking their own charters, asserted that defense was the province of local militia and that the King’s troops were, in effect, standing against Englishmen. The Declaration of Independence would later codify this grievance among its indictments of George III: “He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.”16

The Militia Ideal

Opposition to standing armies was more than a negation; it expressed a positive civic ideal. The colonial militia embodied the republican conviction that the sword should rest in the hands of citizens rather than professionals. The Virginia and Pennsylvania Declarations of Rights both enshrined the principle that “a well-regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, trained to arms, is the proper, natural, and safe defense of a free State.”17 Service in the militia was understood not merely as a duty but as an act of citizenship, linking the defense of the community with participation in self-government.

This militia ideal, however, was as mythic as it was real. Colonial militias varied dramatically in training and discipline, and their record in the early years of the Revolution revealed both valor and incapacity. Yet the symbolism endured: a republic’s defense must arise from its people, not from a standing corps detached from them.18 The image of the citizen-soldier, farmers who would lay aside their ploughs to bear arms and return home after victory, became the moral antithesis of the mercenary. It was this symbolism, rather than any practical military doctrine, that the Founders carried with them into the constitutional debates of the 1780s.

The Revolutionary War and Immediate Aftermath: Crisis and Caution

Overview

The Revolution forced the Founders to confront their deepest political paradox: liberty required defense, but defense required power. No episode tested that paradox more starkly than the formation, use, and disbandment of the Continental Army. The experience of maintaining an army under republican auspices, amid the ever-present danger that it might turn its weapons inward, impressed upon the framers a lasting suspicion of standing forces and an equally lasting conviction that military obedience must rest on consent, not coercion.

The Continental Army and the Problem of Necessity

When Congress resolved in June 1775 to create a “Continental Army,” it did so under duress and with a nervous sense of contradiction. Patriots who only months earlier had denounced the presence of British troops now found themselves compelled to authorize one of their own.19 The army’s initial structure reflected republican anxieties: short-term enlistments, civilian oversight by Congress, and diffuse command among state contingents.20

Washington, appointed commander-in-chief, understood the fragility of this arrangement. He repeatedly warned Congress that reliance on temporary enlistments made the army unreliable and that “discipline is the soul of an army.”21 Yet his insistence on regularity and professionalization provoked unease. To republican eyes, every step toward permanence resembled the European model they despised.

Financial insolvency compounded these fears. The Continental Congress lacked the power to tax, depending instead on requisitions from the states, which often failed to deliver funds or supplies.22 Officers went unpaid, soldiers went unclothed, and desertion spread. The result was a dual anxiety: that the army might collapse for want of means, or that, desperate and armed, it might turn against the civil authorities. Washington’s correspondence reveals his awareness of both dangers. “The army is a dangerous instrument to play with,” he wrote in 1776, “and should be cautiously handled.”23

The Newburgh Conspiracy: Republican Virtue on Trial

The most dramatic manifestation of that danger came in 1783 at Newburgh, New York. With the war effectively won but Congress still delinquent in paying arrears, anonymous letters circulated among the officers urging collective defiance and possibly a march on Philadelphia.24 The so-called Newburgh Conspiracy threatened to invert the Revolution’s very logic: the guardians of liberty becoming its violators. The crisis ended not through institutional safeguards but through Washington’s moral authority. In his address to the assembled officers on March 15, 1783, he appealed to their sense of honor and the sacrifices they had made for a republic “founded upon the purest principles of liberty.” Then, putting on his spectacles, he remarked that he had “grown gray in your service and now find [himself] growing blind,” a moment of humility that defused the mutiny.25

Washington’s self-restraint and deliberate submission to Congress’s authority made Newburgh a founding parable of civil-military subordination.26 In voluntarily resigning his commission later that year, he enacted a gesture so profound that George III, upon hearing of it, reportedly declared, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.”27 The symbolic power of that resignation endured as the moral counterpart to the constitutional principle later embodied in Article II: that the commander-in-chief remains subordinate to law and to the representatives of the people.

The Fragile Peace and Frontier Defense

After disbanding the Continental Army, Congress retained only a token force—about eighty men to guard the western posts and public stores.28 The decision reflected both economic exhaustion and republican conviction. Yet the fledgling Confederation soon confronted practical realities that would test the limits of ideology. British troops remained in the Northwest forts in violation of the Treaty of Paris, Native nations resisted U.S. encroachment, and frontier settlers demanded protection.29

With no adequate army and a dysfunctional militia system, the Confederation government found itself unable to project authority or enforce treaties. This impotence underscored the dilemma: a government too weak to defend its borders or quell domestic unrest risked dissolution as surely as one sustained by a standing army risked tyranny.

The crisis of Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts (1786–87) confirmed the point.30 Though suppressed by a state militia rather than federal troops, the uprising of indebted farmers demanding relief exposed the vulnerability of the republic to internal disorder. For many political leaders, it demonstrated that liberty without order was anarchy, and that order might require a modest, disciplined force under national control.31 Thus, when the Constitutional Convention convened in 1787, the delegates did so in the shadow of both the army’s perils and the Confederation’s impotence. They had seen a republic endangered first by the existence of a standing army and then by its absence. The task was to reconcile the lessons of both.

Constitutional Design: Negotiating Security and Liberty

Overview

When the delegates gathered in Philadelphia in 1787, they carried the full weight of the Revolution’s paradoxes on their shoulders. The experience of the Continental Army and the failures of the Articles of Confederation had taught them that liberty was not self-sustaining; it required a framework capable of defending itself. Yet that same framework, if unrestrained, might reproduce the despotism they had overthrown. The Constitution’s treatment of military power thus emerged as a calculated compromise between necessity and fear, embedding both the capacity for defense and the mechanisms of distrust.

The Constitutional Convention and the Architecture of Restraint

The Philadelphia Convention debates on military power were infrequent but revealing. Few delegates proposed outright prohibitions on standing armies; the memory of Shays’s Rebellion had largely silenced such absolutism. Instead, the question centered on who should control the army and under what constraints.32 The framers ultimately lodged the power to “raise and support Armies” in Congress (Article I, Section 8), not the Executive, but with a crucial proviso: “no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years.”33 This biennial limit on funding became the constitutional embodiment of republican vigilance, a structural barrier ensuring that a standing force could exist only with the recurrent consent of the people’s representatives.

The Convention also confronted the militia question. Article I, Section 8, Clauses 15–16 empowered Congress to call forth, organize, and discipline the militia, while reserving to the states the appointment of officers and authority over training.34 In theory, this divided control prevented the consolidation of all armed power in federal hands. In practice, it created a delicate dual system whose tensions would persist for centuries. The framers understood that no clause could wholly prevent abuse; their strategy was instead to scatter power, to make any dangerous concentration of military authority constitutionally cumbersome.35

Federalists and Anti-Federalists: A Debate on Power and Fear

Outside the Convention, the ratification struggle transformed these structural details into a moral drama. Federalists argued that security required flexibility. In The Federalist Nos. 24–26, Alexander Hamilton dismissed “a wide-spread alarm that the army will be turned against liberty” as a relic of British paranoia.36 The nation’s size and the people’s vigilance, he claimed, were sufficient safeguards; moreover, periodic funding ensured that “a dangerous establishment can never be kept up for a long time.”37 James Madison concurred, contending in Federalist No. 46 that the armed citizenry and state militias would always outnumber any federal army.38

The Anti-Federalists were unconvinced. Writing as “Brutus,” one critic warned that a standing army “in the hands of a powerful executive will be the most formidable instrument of despotism.”39 They pointed to the failures of the English constitution to prevent military abuse despite parliamentary control and demanded explicit constitutional prohibitions.40 Many state ratifying conventions echoed these fears, urging amendments to restrict peacetime armies and to preserve state control of militias.41 The debate was not merely institutional but philosophical: whether liberty was better guarded by dispersion of arms among citizens or by the virtue of those in office.

The Federalists ultimately prevailed, but their victory was contingent on a promise, the addition of a Bill of Rights that would enshrine safeguards against military intrusion.42 The ensuing amendments, while modest in scope, transformed revolutionary suspicion into constitutional principle.

The Bill of Rights and the Constitutional Settlement

The Second and Third Amendments crystallized the Founders’ ambivalence. The Second, guaranteeing that “a well-regulated militia [is] necessary to the security of a free State,” reflected not a modern notion of personal gun ownership but the eighteenth-century conviction that the citizen-militia was the republican counterweight to a standing army.43 The Third, prohibiting the quartering of troops in peacetime without consent, directly answered colonial grievances under the Quartering Acts.44

Beyond these explicit clauses, the Constitution itself institutionalized civilian supremacy. The President, designated Commander-in-Chief, would control the army and navy but only as the executor of laws enacted by Congress.45 Funding remained in legislative hands; the Senate confirmed military appointments; and Congress retained the power to declare war. No branch could wield the sword without the consent of the others.46 As historian Richard H. Kohn observes, “the framers sought to constitutionalize distrust, embedding the Revolution’s moral lessons into the machinery of government.”47

Yet even at its birth, this architecture contained latent contradictions. The very capacity for national defense required the concentration of executive energy, which the Constitution also supplied. Hamilton’s assurance that Congress’s biennial appropriations would suffice to restrain ambition underestimated the elasticity of fear in times of crisis. The Founders could not foresee the rise of a professional army numbering in the hundreds of thousands or the global commitments of later centuries. But they did succeed in encoding their central anxiety into law: that liberty and power must perpetually negotiate their coexistence.

The Early Republic: Practice and Tensions

Overview

The Constitution had resolved the theoretical question of a standing army’s legitimacy but not its practical management. In the early republic, the problem shifted from design to execution, from what the government could do to how it should act. Federalists and Jeffersonians alike found themselves trapped between republican principle and geopolitical necessity. The same generation that had sworn hostility to standing armies soon found one indispensable for governing a continental nation.

The Federalist Era: Building a National Force

George Washington’s presidency tested the new framework almost immediately. In 1791, Congress authorized a modest regular army of a few thousand men, primarily for frontier defense against Native confederacies in the Northwest Territory.48 Even this small establishment provoked opposition from Anti-Federalists in Congress who accused the administration of nurturing “a British model of despotism.”49 Washington defended the measure as a necessity of sovereignty, arguing that “government is not reason; it is not eloquence; it is force,” but force lawfully directed.50

The first major test of civil-military balance came during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, when Pennsylvania farmers protested a federal excise tax.51 Washington, invoking the Militia Act of 1792, called out nearly 13,000 militia to suppress the insurrection, a force larger than any he had commanded since the Revolution.52 His decision was constitutionally unassailable and politically calculated: by using state militia under federal command rather than regular troops, Washington reaffirmed that the people themselves, not a professional corps, would enforce the law.53 The rebellion collapsed without battle, and the episode set a precedent: the army could maintain order, but only under clear civilian authority and with public legitimacy.54

Under John Adams, this principle came under new strain. The Quasi-War with France (1798–1800) led Congress to authorize the expansion of the army and to appoint Alexander Hamilton as its inspector general.55 To Jeffersonian Republicans, the move reeked of monarchical ambition. The standing army, coupled with the Alien and Sedition Acts, seemed to confirm every Anti-Federalist prophecy.56 Adams’s own discomfort with Hamilton’s militarism, culminating in his refusal to launch a land war, demonstrated the lingering power of the Founders’ fear. The army was expanded, but it remained politically suspect, a weapon to be handled with gloves.57

The Jeffersonian Paradox: Dismantling and Depending

Thomas Jefferson entered the presidency vowing to dismantle what he called “the military establishment.”58 In his First Inaugural Address, he celebrated “a militia … our best reliance in peace and for the first moments of war, till regulars may relieve them.”59 Once in office, he drastically reduced the army to about 3,000 men, disbanded several naval ships, and sought to replace permanent fortifications with citizen militias and coastal gunboats.60 To Jefferson, the small army was a symbol of republican virtue: “a standing army is like a standing water, apt to corrupt.”61

Yet international events soon revealed the limits of this idealism. The Barbary Wars (1801–05) and renewed tensions with Britain forced Jefferson to rely increasingly on professional soldiers and sailors.62 His successor, James Madison, inherited a hollowed-out force when the War of 1812 broke out. The militia proved unreliable and undisciplined, and British troops burned Washington in 1814.63 The experience confirmed what Washington had warned decades earlier: militia enthusiasm could not substitute for organization and training. The young republic, committed in principle to civilian soldiery, discovered that the preservation of liberty sometimes demanded the instruments of power.

Institutionalizing Civilian Supremacy

By the 1820s, the fears of the eighteenth century had begun to soften but not to disappear. The army remained small, barely 10,000 men, and its officers were bound by professional codes that reinforced subordination to civil authority.64 The West Point Academy, established in 1802, became not a forge of martial ambition but a school of national service, producing engineers as often as soldiers.65 Congress maintained tight control over appropriations, and no military leader approached the political stature of Washington. The United States thus achieved what the framers had envisioned: a permanent but contained army, integrated into civilian life and devoid of aristocratic identity.

Still, the ideological tension persisted beneath the surface. Episodes such as Andrew Jackson’s quasi-independent command in Florida (1818) and his subsequent invasion of Spanish territory revived old fears about personalist military power.66 Even as the republic expanded and professionalized its forces, the moral inheritance of 1776 remained: the conviction that the army was an instrument, not a master. That principle – born in English pamphlets, refined in colonial resistance, and codified at Philadelphia – had survived the Revolution’s transformation from ideology to governance. The American experiment in civil-military balance had endured its first tests and, for a time, held.

Theoretical Reflection and Historiographical Debates

Overview

By the early nineteenth century, the Founders’ settlement regarding military power had become part of the constitutional landscape, yet its meaning remained contested. The balance they struck, between vigilance and necessity, fear and functionality, has continued to animate American political thought and scholarship. To assess their achievement is to engage not only with the text of the Constitution but with the deeper intellectual tradition from which it sprang and the evolving realities that have tested it ever since.

Ideological Roots and Enduring Contradictions

At its core, the Founders’ distrust of standing armies derived from a republican conception of virtue. Drawing on the civic humanism of Machiavelli, Harrington, and the English Commonwealthmen, they equated freedom with the active participation of citizens in the defense of their polity.67 A republic that relied on mercenaries, or on a permanent corps divorced from civic life, was thought to invite corruption and dependence. The militia, composed of property-owning citizens, symbolized self-rule; the standing army, subordination.68

Yet this ideology contained a paradox that the Founders never fully resolved. A vast republic (spanning oceans, frontiers, and potential enemies) could not rely indefinitely on local enthusiasm and ad hoc militias. Hamilton captured this tension when he wrote that “a nation without a national government is, in my view, an awful spectacle,”69 implying that defense itself was a function of nationhood. The Constitution’s answer (biennial appropriations, legislative supremacy, and dispersed command) was an attempt to institutionalize virtue by design rather than by reliance on character alone.70 It assumed that power could be divided safely, that ambition would counteract ambition, and that public vigilance would remain constant.

The practical history of the early republic, however, revealed how fragile those assumptions were. The army’s expansion during the Quasi-War, its reduction under Jefferson, and its failure during the War of 1812 all exposed the limits of ideological purity.71 The very mechanisms meant to restrain despotism sometimes produced weakness bordering on national humiliation. To many later commentators, this suggested that the Founders had not solved the dilemma of civil-military balance but merely deferred it.

Historiographical Perspectives

Modern historians and political theorists have approached the Founders’ anxiety from divergent angles. The “republican synthesis” of the 1960s and 1970s, articulated by scholars such as Bernard Bailyn and Gordon Wood, interpreted the fear of standing armies as part of a broader republican worldview grounded in virtue and civic participation.72 In this interpretation, the Founders’ distrust of professional soldiers was not simply prudential but moral—a conviction that liberty demanded continual engagement by the citizenry.

By contrast, later revisionists such as Jack Rakove and Joyce Appleby have emphasized the pragmatic rather than ideological dimensions of the settlement.73 To them, the debates over armies and militias reflected less an abstract theory of virtue than a contest over governance: whether sovereignty should rest primarily with the states or the federal center. The “fear of the army,” in this reading, functioned as a proxy for larger anxieties about consolidation and executive power.

More recent scholarship has reexamined these questions in the light of modern civil-military theory. Samuel Huntington’s classic The Soldier and the State (1957) interpreted the Founders’ design as the prototype of “objective control,” in which professionalization, not distrust, safeguards liberty by ensuring political neutrality.74 Others, such as Richard Kohn, argue that the American military tradition has remained faithful to the Founders’ spirit precisely because of the cultural persistence of suspicion, what he calls the “American civil-military gap.”75 The balance between confidence and caution, professionalism and republican fear, continues to define the U.S. military ethos even in the age of a global superpower.

The Founders’ Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

The Founders’ settlement, though conceived in an age of muskets and militias, endures as the moral architecture of American civil-military relations. Their insistence on legislative control, periodic funding, and civilian supremacy has survived revolutions in technology and scale. Yet the modern national security state – with its permanent standing forces, global bases, and intelligence apparatus – poses challenges they could scarcely imagine.76 The question remains whether the institutional mechanisms they devised are sufficient to restrain power in an era when the boundaries between war and peace, foreign and domestic, are increasingly blurred.

Contemporary debates over the deployment of federal troops in domestic crises, the militarization of policing, and executive war powers all echo the eighteenth-century dialogue between Federalists and Anti-Federalists. The Founders’ fear was not of the soldier but of the citizen’s complacency, the erosion of vigilance that allows liberty to yield to expedience.77 In that sense, the distrust of standing armies was less about muskets than about memory: a collective determination never to forget that freedom, once surrendered to the sword, is seldom recovered.

Conclusion

The American Founders inherited from England a profound distrust of military power, tested it in the crucible of revolution, and sought to contain it within the boundaries of law. What emerged from that experience was neither pure idealism nor cynical pragmatism but a durable constitutional ethic: that liberty requires both strength and skepticism. The republic they built was not pacifist; it was wary. Its architects understood that the instruments of defense can become the engines of domination if unchecked by institutional restraint and civic vigilance.

The Revolution had revealed that citizen militias, while noble in spirit, were inadequate alone to secure independence. Yet the memory of British garrisons in colonial streets made a permanent army politically and morally intolerable. The solution the Founders devised (legislative control, periodic funding, state militias, and civilian command) reflected an attempt to domesticate necessity.78 It was an experiment in channeling power through distrust, ensuring that the tools of coercion would remain under the supervision of those they served.

That balance has never been static. In times of crisis, from the Civil War to the Cold War and the twenty-first century’s endless “wars on terror,” the old anxiety about standing armies has reemerged in new forms: the growth of executive authority, the militarization of foreign policy, and the blurred boundary between civil and military spheres.79 Yet each resurgence also testifies to the Founders’ success. Their system of divided power, grounded in suspicion, has repeatedly forced Americans to justify the uses of force before the tribunal of public reason.80

Ultimately, the Founders’ fear of standing armies was not an expression of weakness but of wisdom. They understood that the preservation of freedom depends less on the virtue of rulers than on the vigilance of citizens. The army could defend the nation, but only the people could defend the republic. As George Washington reminded his officers at Newburgh, liberty’s endurance rests not in obedience to command but in fidelity to conscience.81 That warning, tempered by humility and born of experience, remains the most enduring article in the American creed: that a free society must always keep its sword sharp, and its hand upon the hilt, but its conscience above both.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776), §13.

- Declaration of Independence (1776): “He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.”

- Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802 (New York: Free Press, 1975), 12–15.

- Newburgh Conspiracy, Mount Vernon Digital Encyclopedia, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/newburgh-conspiracy.

- George Washington, “Address to the Officers of the Army at Newburgh,” 15 March 1783, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10840.

- Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist Nos. 24–26 (1787–88).

- “Brutus No. 10,” Anti-Federalist Papers (1788).

- U.S. Const. amends. II–III; see also Lawrence Goldstone, “Arms and the Common Man: Standing Army, Militia, and the Second Amendment in the United States,” Law and History Review (2023).

- English Bill of Rights (1689), 1 Will. & Mar. sess. 2 c. 2.

- John Childs, The Army, James II, and the Glorious Revolution (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1980), 47–52.

- John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, Cato’s Letters, no. 96 (1723), in The Independent Whig and Cato’s Letters, ed. Ronald Hamowy (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1995), 681.

- J. C. D. Clark, The Language of Liberty, 1660–1832 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 214.

- Quartering Act of 1765, 5 Geo. III c. 33; Quartering Act of 1774, 14 Geo. III c. 54.

- Hiller B. Zobel, The Boston Massacre (New York: W. W. Norton, 1970), 145–47.

- Samuel Adams, “A Short Address to the People of England,” Boston Gazette, September 12, 1768.

- Declaration of Independence (1776).

- Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776), §13; Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights (1776), art. 13.

- Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword, 5–9.

- Journals of the Continental Congress, 2:91–92 (June 14, 1775).

- Charles Royster, A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character, 1775–1783 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 42–48.

- George Washington to the Continental Congress, 29 September 1776, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0129.

- John Ferling, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 512–16.

- George Washington to the Board of War, 9 February 1776, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-03-02-0178.

- Richard H. Kohn, “The Inside History of the Newburgh Conspiracy,” William and Mary Quarterly 27, no. 2 (April 1970): 187–220.

- George Washington, “Address to the Officers of the Army at Newburgh,” 15 March 1783, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10840.

- Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword, 36–41.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1993), 105.

- Journals of the Continental Congress, 25:803–04 (June 3, 1783).

- Eliga H. Gould, Among the Powers of the Earth: The American Revolution and the Making of a New World Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 89–94.

- Leonard L. Richards, Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

- Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Knopf, 1996), 38–42.

- Max M. Edling, A Revolution in Favor of Government: Origins of the U.S. Constitution and the Making of the American State (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 171–75.

- U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 12.

- U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cls. 15–16.

- Forrest McDonald, Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1985), 254–58.

- Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist No. 24 (1787).

- Ibid., No. 25.

- James Madison, The Federalist No. 46 (1788).

- “Brutus No. 10,” The Anti-Federalist Papers (1788).

- Saul Cornell, The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 62–64.

- Debates of the Virginia Ratifying Convention, June 1788, in The Founders’ Constitution, vol. 3, art. 1, sec. 8, cl. 12.

- Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 449–52.

- Lawrence Goldstone, “Arms and the Common Man: Standing Army, Militia, and the Second Amendment in the United States,” Law and History Review 41, no. 1 (2023): 57–59.

- U.S. Const. amend. III.

- U.S. Const. art. II, § 2.

- Louis Fisher, Presidential War Power, 3rd ed. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013), 11–14.

- Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword, 68.

- An Act for Raising and Adding Another Regiment to the Military Establishment of the United States, 3 March 1791, U.S. Statutes at Large 1:222.

- Annals of Congress, 1st Cong., 3rd sess. (1791), 1403–05.

- George Washington, quoted in John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington, vol. 35 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1940), 300.

- Thomas P. Slaughter, The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986).

- Militia Act of 1792, 1 Stat. 264.

- James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, 14 September 1794, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-15-02-0053.

- John Ferling, Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 112–14.

- Alexander DeConde, The Quasi-War: The Politics and Diplomacy of the Undeclared War with France, 1797–1801 (New York: Scribner’s, 1966), 45–52.

- Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 691–96.

- John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 October 1798, in The Adams Papers, ed. L. H. Butterfield (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973), 13:219–21.

- Thomas Jefferson to Elbridge Gerry, 26 January 1799, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-30-02-0390.

- Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address, 4 March 1801, Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/jefinau1.asp.

- Dumas Malone, Jefferson the President: First Term, 1801–1805 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970), 131–33.

- Jefferson, quoted in Henry Adams, History of the United States of America during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Library of America, 1986), 2:55.

- Frank Lambert, The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World (New York: Hill and Wang, 2005), 84–88.

- Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989), 163–69.

- Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil–Military Relations (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957), 165–69.

- Stephen E. Ambrose, Duty, Honor, Country: A History of West Point (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1966), 47–49.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and His Indian Wars (New York: Viking, 2001), 88–91.

- J. G. A. Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975), 506–12.

- Quentin Skinner, Liberty Before Liberalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 79–82.

- Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist No. 85 (1788).

- James Madison, The Federalist No. 51 (1788).

- Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812, 312–16.

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967); Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969).

- Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings; Joyce Appleby, Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992).

- Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State, 80–84.

- Richard H. Kohn, “How Democracies Control the Military,” Journal of Democracy 8, no. 4 (1997): 140–53.

- Eliot A. Cohen, Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime (New York: Free Press, 2002), 218–21.

- Andrew J. Bacevich, The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 10–12.

- Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword, 285–87.

- Andrew J. Bacevich, The New American Militarism, 16–22.

- Louis Fisher, Presidential War Power, 201–06.

- George Washington, “Address to the Officers of the Army at Newburgh,” 15 March 1783, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10840.

Bibliography

- Adams, Henry. History of the United States of America during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Library of America, 1986.

- Adams, John. The Adams Papers. Edited by L. H. Butterfield. Vol. 13. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973.

- Adams, Samuel. “A Short Address to the People of England.” Boston Gazette, September 12, 1768.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Duty, Honor, Country: A History of West Point. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1966.

- Annals of Congress. 1st Cong., 3rd sess. (1791).

- An Act for Raising and Adding Another Regiment to the Military Establishment of the United States. March 3, 1791. U.S. Statutes at Large 1:222.

- The Anti-Federalist Papers. 1788.

- Appleby, Joyce. Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Avalon Project, Yale Law School. “Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address.” March 4, 1801. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/jefinau1.asp.

- Bacevich, Andrew J. The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Childs, John. The Army, James II, and the Glorious Revolution. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1980.

- Clark, J. C. D. The Language of Liberty, 1660–1832. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Cohen, Eliot A. Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime. New York: Free Press, 2002.

- Cornell, Saul. The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

- Debates of the Virginia Ratifying Convention. June 1788. In The Founders’ Constitution, vol. 3, art. 1, sec. 8, cl. 12.

- Declaration of Independence. 1776.

- DeConde, Alexander. The Quasi-War: The Politics and Diplomacy of the Undeclared War with France, 1797–1801. New York: Scribner’s, 1966.

- Edling, Max M. A Revolution in Favor of Government: Origins of the U.S. Constitution and the Making of the American State. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Elkins, Stanley, and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- English Bill of Rights. 1689. 1 Will. & Mar. sess. 2 c. 2.

- Ferling, John. Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- ———. Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Fisher, Louis. Presidential War Power. 3rd ed. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

- Gould, Eliga H. Among the Powers of the Earth: The American Revolution and the Making of a New World Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Goldstone, Lawrence. “Arms and the Common Man: Standing Army, Militia, and the Second Amendment in the United States.” Law and History Review 41, no. 1 (2023): 57–59.

- Hamilton, Alexander. The Federalist Papers. Nos. 24–26, 85. 1787–88.

- Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

- Huntington, Samuel P. The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil–Military Relations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957.

- Jefferson, Thomas. “First Inaugural Address.” March 4, 1801. Avalon Project, Yale Law School.

- ———. Letter to Elbridge Gerry, January 26, 1799. Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-30-02-0390.

- Kohn, Richard H. Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802. New York: Free Press, 1975.

- ———. “The Inside History of the Newburgh Conspiracy.” William and Mary Quarterly 27, no. 2 (April 1970): 187–220.

- ———. “How Democracies Control the Military.” Journal of Democracy 8, no. 4 (1997): 140–53.

- Lambert, Frank. The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World. New York: Hill and Wang, 2005.

- Madison, James. The Federalist Papers. Nos. 46, 51. 1788.

- ———. Letter to Thomas Jefferson, September 14, 1794. Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-15-02-0053.

- Malone, Dumas. Jefferson the President: First Term, 1801–1805. Boston: Little, Brown, 1970.

- Maier, Pauline. Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

- McDonald, Forrest. Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1985.

- Militia Act of 1792. 1 Stat. 264.

- Mount Vernon Digital Encyclopedia. “Newburgh Conspiracy.” https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/newburgh-conspiracy.

- The Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights. 1776.

- Pocock, J. G. A. The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- Quartering Act of 1765. 5 Geo. III c. 33; Quartering Act of 1774. 14 Geo. III c. 54.

- Rakove, Jack N. Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution. New York: Knopf, 1996.

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and His Indian Wars. New York: Viking, 2001.

- Richards, Leonard L. Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

- Royster, Charles. A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character, 1775–1783. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979.

- Skinner, Quentin. Liberty Before Liberalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Slaughter, Thomas P. The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Trenchard, John, and Thomas Gordon. Cato’s Letters. In The Independent Whig and Cato’s Letters. Edited by Ronald Hamowy. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1995.

- U.S. Constitution. 1787.

- U.S. Constitution, Amendments II and III.

- Virginia Declaration of Rights. 1776.

- Washington, George. “Address to the Officers of the Army at Newburgh.” March 15, 1783. Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10840.

- ———. Letters to the Continental Congress and the Board of War, 1776. Founders Online.

- ———. The Writings of George Washington. Edited by John C. Fitzpatrick. Vol. 35. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1940.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

- ———. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1993.

- Zobel, Hiller B. The Boston Massacre. New York: W. W. Norton, 1970.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.08.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.