The story of the Agapemonites is not merely a curiosity of Victorian eccentricity but a revealing chapter in the history of belief itself.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Rise of Prophets in an Age of Doubt

In the middle decades of the nineteenth century, when faith and reason clashed in the British imagination, new prophets emerged to fill the void left by a disintegrating religious consensus. The Agapemonites, formally the Community of the Son of Man, were one such movement. Founded by Henry James Prince in 1846, they promised a return to primitive Christian love and a foretaste of divine perfection on earth. Their “Abode of Love” in Spaxton, Somerset, was envisioned as a spiritual Eden, a sanctuary from what Prince called the “world of Babylon.” In reality, it became a crucible of manipulation, sensual mysticism, and authoritarian control, reflecting both the intense spiritual hunger and the profound social anxiety of Victorian religion.1

Prince’s transformation from Anglican curate to self-proclaimed “Beloved” followed a pattern familiar in millenarian sects: charisma became revelation, and revelation became authority. His followers were not merely believers but participants in a theology of possession, where divine love (agape) was made flesh through the prophet himself.2 Within a decade, the Agapemone had gained notoriety across Britain for its scandalous rumors of “spiritual marriages” and the apparent merging of eroticism and salvation. What began as a reaction to religious coldness and moral rigidity evolved into a drama of spiritual tyranny, one that would foreshadow later sects blending ecstatic devotion with sexual power.

By the time Prince’s chosen successor, John Hugh Smyth-Pigott, declared himself the reincarnation of Christ in 1902, the movement had crossed from heresy into blasphemous theater. The Agapemonites’ story, spanning over a century from the beginning of the Victorian era in 1846 to the beginning of the New Elizabethan age in 1956, reveals the darker edges of Victorian spirituality: the yearning for certainty amid doubt, the eroticization of the divine, and the perils of absolute conviction. Their saga stands as a cautionary reflection on how charisma can eclipse conscience, turning faith into spectacle and devotion into domination.3

The Making of “The Beloved”: Henry James Prince and Charismatic Authority

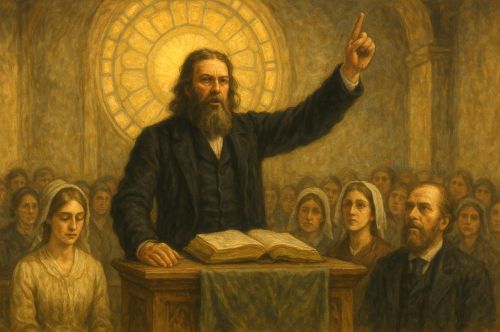

Henry James Prince was born in 1811, trained as a physician before turning to theology, and entered the Anglican ministry during a period of intense evangelical ferment. His early preaching in Somerset attracted both curiosity and alarm; parishioners noted his strange blend of medical precision and mystical confidence. In 1842, he was expelled from the Church of England after repeated confrontations with ecclesiastical authorities over his claim to possess “spiritual perfection.”4 He soon gathered around him a small circle of devoted followers who believed that he, like Christ, was incapable of sin. This conviction became the foundation of the Agapemonite theology, the belief that one could, through total submission to Prince, attain divine union and physical immortality.

Prince’s charisma drew heavily on the patterns of revivalism sweeping through mid-nineteenth-century Britain. His sermons replaced the language of repentance with that of possession: followers were not merely converted but “taken up” into the divine.5 He taught that the true believer no longer lived by moral law but by the indwelling presence of God, a doctrine he illustrated with his own supposed transfiguration. His followers called him “The Beloved,” a title suggesting both emotional intimacy and divine uniqueness. As he declared himself “the vessel of the Spirit,” his control deepened over those who sought in him a living Christ.

The creation of the Agapemone in 1846, literally “Abode of Love,” transformed Prince’s vision into architecture. The community, established in the quiet village of Spaxton, became a walled enclave symbolizing both separation from the profane world and entry into divine mystery. Wealthy women, many widowed or unmarried, financed the construction and soon became his most loyal disciples. Within this cloistered space, religious devotion intertwined with sensual mysticism. Prince instituted “spiritual marriages” between himself and selected women, ceremonies justified as sacraments of divine love rather than acts of carnal indulgence.6

Contemporary observers were divided between outrage and fascination. Newspapers like The Times and The Western Gazette chronicled the cult’s practices with moral indignation, portraying the Agapemone as a scandalous inversion of Christian virtue. Church authorities denounced it as heresy, yet the movement endured. Its secrecy, coupled with Prince’s imperviousness to public condemnation, enhanced his aura of sanctity among followers. By the time of his death in 1899, the Agapemone had weathered decades of scandal and isolation, standing as a self-contained kingdom of divine love under a prophet who believed himself the incarnate perfection of God.7

Erotic Theology: The Cult of Divine Union and “Spiritual Brides”

The Agapemonite doctrine of “divine love” was never a metaphor. Within Henry James Prince’s theology, physical union became a sacrament of spiritual communion. His interpretation of agape (the selfless, godly love of the New Testament) was reimagined through the body rather than the spirit. To the faithful, Prince’s sexual relationships with female adherents were not sins but signs of sanctification, a re-enactment of divine creation itself.8 This doctrine, cloaked in biblical language, transformed intimacy into revelation. The community’s rituals blurred the line between marriage and mysticism, constructing a theology that made Prince’s authority absolute and women’s submission redemptive.

The “spiritual brides” who surrounded Prince embodied the paradox of Victorian womanhood. In an age that prized chastity and subservience, these women found themselves told that transgression was obedience. Many were educated, independent, and wealthy, traits that made them both targets and instruments of the movement’s survival.9 Within the Agapemone, female sexuality was divinized and controlled in equal measure. To love the Beloved was to surrender entirely: wealth, body, and will. Children born of these “spiritual unions” were described not as bastards but as “children of promise,” incarnations of divine purity untouched by worldly sin.

Public reaction to this theology was fierce. Victorian newspapers sensationalized the sect’s practices, fusing moral outrage with fascination. Reports of women entering Prince’s “inner chamber” or bearing “holy children” were circulated as cautionary tales about the dangers of religious enthusiasm unmoored from doctrine.10 Church authorities condemned the Agapemone as a corruption of Christianity, yet their rhetoric only intensified public curiosity. In the moral economy of the age, erotic mysticism was scandalous precisely because it gave visible form to what polite religion repressed, the body’s role in spiritual experience.11

The theology of divine union also prefigured later currents in occultism and spiritualism. Scholars such as Alex Owen have noted that the Agapemonite emphasis on embodiment as revelation parallels the ecstatic practices of late Victorian spiritualist circles, where women served as mediums of the divine.12 Yet Prince’s innovation was more authoritarian: he alone mediated access to the sacred. What others experienced as trance or possession, he institutionalized as hierarchy. By merging love with obedience, he created a theology where devotion became indistinguishable from domination, a structure that would reach its climax under his successor.

John Hugh Smyth-Pigott and the Reincarnation of the Messiah

When Henry James Prince died in 1899, the Agapemone appeared destined to wither with him. Instead, it entered a second, more spectacular life under the leadership of John Hugh Smyth-Pigott. Educated, articulate, and socially connected, Smyth-Pigott joined the community in the 1890s and quickly rose to prominence as Prince’s favored disciple.13 By the turn of the century, he began to style himself as the next vessel of divine truth, claiming that the Spirit which had inhabited Prince had now descended upon him. His assumption of leadership was marked by the same fusion of mysticism and sensuality that had defined his predecessor, but with a new theatricality and scale suited to Edwardian London.

In 1902, Smyth-Pigott proclaimed himself to be “The Messiah,” the reincarnated Christ returned to complete the work begun in Somerset.14 The announcement, made before a congregation at the Agapemone’s London outpost in Clapton, sent shockwaves through the press. Reporters described scenes of rapture and hysteria as followers hailed him as the Second Coming. To the broader public, however, it was blasphemy on parade. Crowds gathered outside the gates shouting “Crucify him!” while newspapers carried lurid accounts of the “Sex Messiah of Clapton.” The sensationalism transformed a small sect into a national scandal, turning Smyth-Pigott into a caricature of the fallen prophet, half Christ, half libertine.

The Clapton Agapemone was unlike the rustic isolation of Spaxton. Set amid the growing suburb of Hackney, it reflected urban wealth and the aesthetic of a new century. The building itself was opulent: stained glass, fine furnishings, and manicured gardens. Inside, Smyth-Pigott presided over a court of “spiritual brides” who served as both disciples and companions.15 As with Prince, these women were told that intimacy with the prophet was a sacrament of divine love. Several bore children, whom Smyth-Pigott declared to be “born of God.” The community’s hierarchy was rigidly gendered (women as vessels of the Spirit, men as its interpreters) and sustained by wealth inherited from earlier converts.

The press eagerly chronicled every scandal. The Daily Mail and Illustrated London News portrayed Smyth-Pigott as both villain and curiosity, their reports filled with images of the “Abode of Love” as a gilded prison.16 Yet despite public outrage, legal authorities found little ground for prosecution. The Agapemone remained technically within the law, its secrecy shielding it from exposure. Behind the walls, Smyth-Pigott’s rule grew more autocratic. He declared that the Last Judgment had already occurred and that his followers were living in the New Jerusalem. Dissenters were excommunicated, and even private doubt was treated as rebellion against God.

The later years of Smyth-Pigott’s reign were marked by decline rather than revival. As his health deteriorated and the fervor of early disciples waned, the community retreated into isolation. Financial mismanagement eroded its resources, and the deaths of key benefactors left it increasingly dependent on a shrinking inner circle. Smyth-Pigott’s final years were spent at Spaxton, surrounded by a few loyal followers and the remnants of his “holy family.”17 When he died in 1927, he was buried beside Prince, two self-proclaimed incarnations of Christ, entombed within the same walls that had once echoed with hymns to divine love.

Yet Smyth-Pigott’s legacy lingered as a curious footnote in the history of English religion. His career encapsulated the collision between modernity and mysticism, showing how charisma could flourish even in an age of reason. Scholars such as Ronald Matthews later identified him as part of a pattern of “English messiahs,” figures who exploited the religious vacuum left by declining church authority.18 The Agapemone’s endurance into the twentieth century demonstrated that Victorian spiritual hunger did not die with the century itself; it merely changed its face. In Smyth-Pigott’s Christology of desire, one sees both the climax and collapse of a vision that began in faith and ended in delusion.

The Afterlife of a Cult: From Somerset to Oblivion (1919–1956)

When Smyth-Pigott died in 1927, few outside Spaxton took notice. The newspapers that once mocked his “Messiahship” now treated the Agapemone as a relic, an eccentric remnant of the Victorian age. Yet within its walls, the cult did not die with him. Leadership passed quietly to one of his closest spiritual brides, Ruth Preece, whose authority was rooted not in revelation but inheritance. She presided over what remained of the community with a mixture of austerity and nostalgia, preserving the image of the Agapemone as sacred ground even as belief itself withered.19

By the 1930s, the Agapemone had become less a religious movement than a private estate inhabited by a dwindling family of the faithful. The once-lavish chapel stood largely unused, its stained-glass windows depicting Prince and Smyth-Pigott as divine figures in the continuum of salvation history.20 Few new converts arrived; the children of earlier “spiritual unions” grew up in quiet isolation, their lives shaped by secrecy and the stigma attached to their parentage. The community’s wealth, sustained for decades by generous inheritances, dwindled under the strain of maintaining its properties. Without Prince’s charisma or Smyth-Pigott’s theatrical leadership, the Abode of Love became an anachronism, an enclave of silence amid the modern world.

The outside world viewed the Agapemone through the lens of sensational memory. Journalists occasionally revisited Spaxton, describing it as a “haunted Eden” where the past lingered like a ghost.21 Former residents spoke cautiously, recounting memories of rigid routines, segregated quarters, and an atmosphere more melancholic than ecstatic. What had once been heralded as a foretaste of paradise had hardened into ritualized nostalgia. The “Beloved” and “Messiah” were still commemorated with small gatherings, but the theology that sustained them had lost coherence. To later generations, the Agapemone’s isolation seemed less like sanctity than denial, a refusal to admit the world’s indifference.

The Second World War deepened this isolation. Food shortages and rationing forced the community to sell parcels of land, and many younger members left to work or serve elsewhere. The war’s devastation exposed the irrelevance of the Agapemone’s millenarian promise; apocalypse was no longer a metaphor but a historical reality.22 By the 1950s, fewer than a dozen residents remained. They lived modestly, tended the grounds, and maintained a small fund to keep the estate solvent. The language of revelation had vanished from their correspondence; in its place were letters about gardens, illness, and the management of dwindling property.

When the Agapemone was finally sold in 1956, it marked the quiet end of one of England’s strangest religious experiments. The property passed into private hands, and the great chapel was later converted for secular use. The remaining adherents dispersed, some moving into nearby villages, others simply vanishing into anonymity. The movement’s archives (letters, sermons, and family records) were scattered, some preserved in local collections, others lost.23 What remained was not a faith but a cautionary legend, revived periodically by journalists and historians as a symbol of religious excess and erotic delusion.

Yet even in its demise, the Agapemone reveals something enduring about modern spirituality. It demonstrates how the yearning for divine intimacy, once satisfied by church and scripture, can seek new vessels when institutional faith falters.24 The cult’s survival for more than a century cannot be explained by gullibility alone; it reflects a deeper cultural hunger for meaning beyond reason’s reach. By 1956, that hunger had moved elsewhere, to spiritualism, psychology, and new religious movements that reimagined transcendence for a postwar world. The “Abode of Love” crumbled, but the need that built it never disappeared.

Conclusion: Charisma, Sex, and the Persistence of the Sacred

The story of the Agapemonites is not merely a curiosity of Victorian eccentricity but a revealing chapter in the history of belief itself. Across its century-long existence, the community moved through recognizable theological stages: revelation, ritual, and ruin. What began as Henry James Prince’s personal vision of divine perfection matured into a theology of possession, then collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions. The promise of absolute purity was undone by the very human desires it sought to sanctify. The Agapemone’s fusion of erotic love and religious devotion exposed the deep instability of any faith built on the charisma of one man.25

Prince’s transformation into the “Beloved” embodied the Victorian crisis of authority. His charisma offered certainty in an age of skepticism, yet it also revealed how easily the hunger for spiritual intimacy could be manipulated into submission. Smyth-Pigott’s later self-apotheosis as the reincarnated Christ carried that logic to its conclusion: when revelation becomes personality, and personality becomes godhood, religion collapses into performance.26 The sect’s longevity, lasting into the mid-twentieth century, shows that charisma can outlive conviction. It survives not because its doctrines endure, but because its structure of devotion satisfies a psychological need that theology alone cannot.

The Agapemone also stands as a mirror of its cultural moment. Its obsession with purity and love reflected the repressed sexual anxieties of Victorian society, while its scandals provided a safe arena for those same fears to be condemned and consumed.27 The movement’s women were both liberated and imprisoned, liberated from conventional morality, yet bound to a prophet’s will. Their stories complicate the notion of female passivity, for within this sect, women were not merely victims but central actors in the creation and perpetuation of the cult’s mythology.

When the gates of Spaxton finally closed in 1956, the Abode of Love did not disappear so much as dissolve into modernity’s wider landscape of belief. In its ruins lay the same paradox that haunts every age of religious enthusiasm: the yearning to touch the divine through human means.28 The Agapemonites’ downfall illustrates that charisma without accountability, and love without boundaries, inevitably corrupt both faith and flesh. Yet their history also reminds us that the desire for transcendence (whether through reason, ecstasy, or love) remains irrepressible. The Agapemone failed, but the longing that created it endures, forever searching for new prophets, new rituals, and new abodes of love.

Appendix

Footnotes

- J. F. C. Harrison, The Second Coming: Popular Millenarianism, 1780–1850 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979), 187–189.

- William Sims Bainbridge, The Sociology of Religious Movements (London: Routledge, 1997), 214–217.

- Ronald Matthews, English Messiahs: Studies of Six English Pretenders, 1656-1927 (London: Methuen, 1936), 92–95.

- Matthews, English Messiahs, 64–68.

- J. F. C. Harrison, The Second Coming, 191–193.

- Alex Owen, The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 117–119.

- The Times (London), March 14, 1849; Western Gazette (Yeovil), August 2, 1851.

- William Sims Bainbridge, The Sociology of Religious Movements (London: Routledge, 1997), 215–216.

- Owen, The Darkened Room, 120–122.

- The Times (London), September 4, 1856.

- Barbara Taylor, Eve and the New Jerusalem: Socialism and Feminism in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Pantheon, 1983), 274–275.

- Owen, The Darkened Room, 128–130.

- Matthews, English Messiahs, 95–97.

- Daily Mail (London), September 8, 1902.

- Owen, The Darkened Room, 132–134.

- Illustrated London News (London), October 4, 1902.

- Christopher Partridge, Encyclopedia of New Religious Movements (London: Routledge, 2004), 20–21.

- Matthews, English Messiahs, 102–104.

- David V. Barrett, The New Believers: Sects, ‘Cults’, and Alternative Religions (London: Cassell, 2001), 47–48.

- Partridge, Encyclopedia of New Religious Movements, 21–22.

- Somerset County Gazette (Taunton), March 9, 1935.

- Barrett, The New Believers, 49.

- Somerset County Gazette (Taunton), July 7, 1956.

- Harrison, The Second Coming, 199–201.

- Bainbridge, The Sociology of Religious Movements, 218–220.

- Matthews, English Messiahs, 105–106.

- Owen, The Darkened Room, 138–139.

- Partridge, Encyclopedia of New Religious Movements, 22–23.

Bibliography

- Bainbridge, William Sims. The Sociology of Religious Movements. London: Routledge, 1997.

- Barrett, David V. The New Believers: Sects, ‘Cults’, and Alternative Religions. London: Cassell, 2001.

- Harrison, J. F. C. The Second Coming: Popular Millenarianism, 1780–1850. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979.

- Matthews, Ronald. English Messiahs: Studies of Six English Pretenders, 1656-1927. London: Methuen, 1936.

- Owen, Alex. The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

- Partridge, Christopher, ed. Encyclopedia of New Religious Movements. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Taylor, Barbara. Eve and the New Jerusalem: Socialism and Feminism in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Pantheon, 1983.

- Daily Mail (London). September 8, 1902.

- Illustrated London News (London). October 4, 1902.

- Somerset County Gazette (Taunton). March 9, 1935; July 7, 1956.

- The Times (London). March 14, 1849; September 4, 1856.

- Western Gazette (Yeovil). August 2, 1851.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.