The Wanli Emperor’s long withdrawal from governance represents one of the most consequential failures of leadership in the history of imperial China.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Emperor Who Stopped Governing

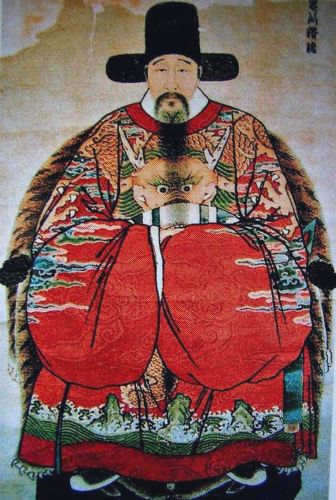

In the long history of imperial China, few reigns embody the destructive potential of political paralysis more vividly than that of the Wanli Emperor (Zhu Yijun, r. 1572–1620). What began as a period of disciplined reform and stability under the guidance of his grand secretary, Zhang Juzheng, devolved after 1582 into a protracted era of neglect. For nearly three decades, the Ming government drifted without effective leadership, as the emperor withdrew from court audiences, refused to read memorials, and left countless bureaucratic posts unfilled. This unprecedented withdrawal from governance, what historians later termed the political neglect of the Wanli era, transformed one of China’s most centralized monarchies into an empire paralyzed by silence.

Under Zhang Juzheng’s mentorship, the young Wanli emperor had initially presided over one of the Ming dynasty’s most efficient decades. Zhang’s administrative reforms, especially the “Single Whip” tax system, had streamlined state revenue and disciplined a fractious bureaucracy. Yet this success proved fragile. Zhang’s death exposed the emperor’s own resentment toward his tutor’s dominance and the bureaucratic moralism that had constrained him. By the late 1580s, his relationship with his officials had soured beyond repair. Conflicts over court protocol, moral authority, and especially the question of imperial succession ignited a bitter power struggle. The bureaucracy demanded that Wanli designate his eldest son, Zhu Changluo, as heir, in accordance with Confucian orthodoxy; the emperor instead favored his younger son by his beloved consort, Lady Zheng. When his ministers refused to yield, Wanli ceased to engage with them altogether.1

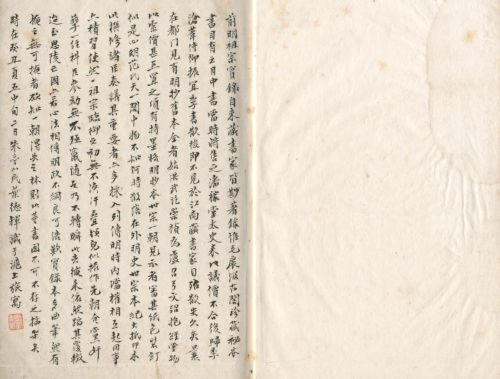

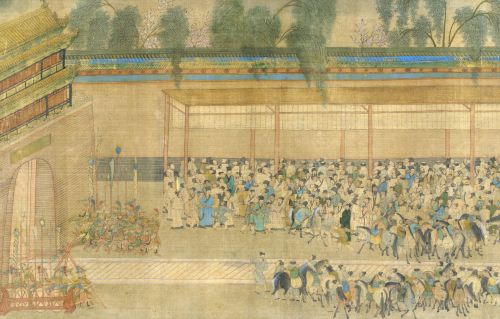

The result was a government in suspension. Court officials continued to gather for morning audiences before an empty throne, performing rituals for an absent sovereign. Memorials accumulated unread, promotions went unapproved, and provincial appointments remained vacant. The Veritable Records (Ming Shilu) describe months passing without a single imperial directive, while factional conflicts between reformist and conservative literati metastasized into open hostility.2 The Wanli Emperor’s silence was not mere lethargy but a calculated form of protest, an assertion of autocratic prerogative against the moralizing bureaucracy that sought to limit him. In abdicating daily governance, he reasserted imperial sovereignty through withdrawal, transforming inaction into defiance.

This decades-long stalemate crippled the Ming administration at every level. Without central coordination, fiscal shortages deepened, military preparedness deteriorated, and corruption became endemic. The bureaucratic ethos of moral remonstrance, once the backbone of Confucian governance, degenerated into partisan purism and self-destruction. By the time of Wanli’s death in 1620, the Ming dynasty was a hollow structure sustained more by ritual than by policy. The emperor’s long retreat from public duty revealed a paradox at the heart of autocracy: that power, when hoarded rather than exercised, erodes the very state it claims to preserve.

The following essay examines the Wanli Emperor’s political withdrawal not as an isolated failure of temperament but as a structural collapse of Ming governance. It traces the transition from Zhang Juzheng’s reformist decade to the emperor’s personal disengagement, explores the bureaucratic conflicts that fueled his defiance, and assesses the consequences of prolonged administrative paralysis. In doing so, it situates the Wanli reign within the larger pattern of late imperial decline, arguing that the emperor’s silence was both a symptom of moral rigidity and a catalyst for the Ming dynasty’s eventual downfall.

The Legacy of Zhang Juzheng and the Wanli Reforms (1572–1582)

When the nine-year-old Zhu Yijun ascended the throne in 1572, the Ming dynasty stood at a crossroads between renewal and decline. His tutor and Grand Secretary, Zhang Juzheng, assumed the regency with a singular vision of restoring administrative discipline and fiscal solvency. Under Zhang’s direction, the empire experienced a remarkable decade of recovery. Through the “Single Whip Reform” (yitiao bianfa), he consolidated various levies into a unified silver tax, simplifying collection and stabilizing the treasury.3 This reform enabled the central government to maintain regular military pay, reduce corruption among local officials, and restore confidence in the imperial administration. At the same time, Zhang’s rigid enforcement of bureaucratic accountability, including regular audits and stringent evaluations of provincial performance, reasserted a sense of order within the state that had eroded since the mid-sixteenth century.

Yet Zhang’s reforms also sowed the seeds of future discontent. His concentration of power alienated both conservative literati and other grand secretaries, who viewed his dominance as autocratic. To secure his program, Zhang employed a network of loyal subordinates and eunuchs who bypassed the usual channels of memorial submission, creating resentment among officials accustomed to more collegial deliberation.4 While his administrative efficiency brought stability, it also curtailed the emperor’s autonomy. Wanli’s formative years were thus spent under a regime that emphasized obedience, fiscal austerity, and strict bureaucratic hierarchy. This early tutelage, while effective, left the young ruler resentful of the moral and procedural strictures imposed upon him.

After Zhang’s death in 1582, the emperor’s latent frustration quickly surfaced. Freed from his mentor’s oversight, Wanli began to dismantle aspects of the reformist system that had kept his power in check. He restored dismissed courtiers, relaxed tax enforcement, and increasingly withdrew from direct involvement in governance. The bureaucracy, long conditioned to Zhang’s authority, found itself without direction.5 The erosion of central oversight reintroduced inefficiency and revived factional infighting, as competing officials sought to claim influence over the inexperienced monarch.

Historians have often interpreted this transition as a turning point in Ming political culture. Ray Huang described 1587, a seemingly uneventful year during Wanli’s reign, as emblematic of a government that “functioned in form but not in spirit,” a state outwardly stable yet inwardly stagnant.6 Zhang’s death removed the one figure capable of balancing imperial prerogative with bureaucratic accountability. The emperor, having internalized both dependency and resentment, came to see active governance as synonymous with submission to a moralizing bureaucracy. In the years that followed, his withdrawal from daily administration would transform personal grievance into state paralysis, inaugurating one of the most enduring crises in imperial Chinese history.

Bureaucratic Conflict and the Succession Dispute

The rupture between the Wanli Emperor and his officials deepened in the late 1580s, as the court became consumed by a bitter conflict over the question of succession. What began as a private matter of familial preference soon evolved into a constitutional crisis within the Confucian political order. The emperor favored Zhu Changxun, his third son by Consort Zheng, and intended to make him crown prince. However, the bureaucracy, invoking the orthodox principle of primogeniture, demanded that his eldest son, Zhu Changluo, born to a lesser-ranked consort, inherit the throne. The dispute quickly metastasized into a confrontation between imperial will and bureaucratic ideology.7

For the scholar-officials, the succession question represented more than adherence to ritual propriety; it was a test of moral legitimacy and bureaucratic authority. Since the early Ming, Confucian governance had emphasized the monarch’s duty to embody ethical restraint and deference to ritual norms. The emperor’s resistance to these expectations threatened the ideological foundation of bureaucratic rule. In response, ministers submitted a torrent of memorials denouncing the emperor’s favoritism, framing it as a violation of both filial piety and dynastic order.8 Many of these remonstrances were couched in the moralizing tone characteristic of late Ming political culture, with officials asserting the right, and duty, to correct imperial misconduct. The emperor, humiliated by what he perceived as public moral lecturing, reacted with increasing hostility.

By 1589, Wanli’s patience had collapsed entirely. Refusing to yield, he began systematically ignoring memorials on all matters, not just those concerning the heir. The number of court audiences sharply declined, and the bureaucratic machinery of the Ming state began to stall.9 As the Ming Shilu records, months would pass without imperial decrees being issued, leaving vacancies in key offices unfilled. Ministers continued to meet in the Hall of Literary Glory to perform their daily audiences, but the emperor’s chair remained empty. In one instance, a censor lamented that “the Son of Heaven hides his light, and the hundred officials stand before shadows.”10

The succession dispute thus exposed the fault line between Confucian moralism and imperial sovereignty. To the emperor, the incessant remonstrations embodied the suffocating hypocrisy of a bureaucracy more loyal to principle than to the monarch. To the officials, his silence confirmed moral decay at the heart of the throne. In reality, both sides were locked in a self-destructive impasse: the bureaucracy demanded virtue from a ruler who refused to perform it, while the ruler punished defiance by withholding governance itself. The result was a political equilibrium defined by inaction, a government that existed in ceremony but not in function.11

The Politics of Withdrawal: Government by Absence

The Wanli Emperor’s retreat from governance after the succession crisis marked one of the most prolonged and deliberate acts of political withdrawal in Chinese imperial history. Beginning in the early 1590s, he ceased to hold regular morning audiences, rarely appeared before his ministers, and refused to approve even routine appointments. Over time, this silence hardened into policy. The court functioned in name only; memorials accumulated unopened in the palace archives, while urgent military and fiscal matters languished without response.12 Officials could do little but continue performing their daily rituals before an empty throne, maintaining the illusion of imperial presence while the machinery of the state corroded. The emperor’s absence became both a personal protest and a political statement, an assertion that the sovereign need not submit to bureaucratic constraint.

For Wanli, this withdrawal was not a collapse of will but an act of defiance. He had grown convinced that the bureaucratic elite, with their incessant moralizing, sought to govern through him rather than under him. By refusing to engage, he reversed the dynamic: instead of submitting to their petitions, he rendered them meaningless through silence. As Ray Huang observed, this inaction was “governance through non-governance,” a deliberate strategy to reclaim imperial autonomy from a moralizing literati class.13 Yet the cost of this stance was catastrophic. In a Confucian system dependent on imperial initiative, the emperor’s silence paralyzed the entire chain of command. Ministries could not act without edicts, provincial officials hesitated to collect taxes or mobilize troops, and the central treasury fell into disarray. The Ming bureaucracy, accustomed to moral discourse rather than managerial independence, proved incapable of adapting.

The effects of the emperor’s absence were soon visible in the capital itself. Contemporary memorials describe the palace gates sealed for weeks, sometimes months, while eunuchs relayed sparse and often contradictory messages from within the inner court.14 Grand secretaries pleaded for the emperor’s return to audiences, citing the dangers of administrative vacuum and the growing audacity of self-serving officials. Their memorials went unanswered. The vacuum also emboldened eunuch factions, who exploited their proximity to the emperor to act as intermediaries in state affairs. The balance between the inner and outer courts, carefully maintained under Zhang Juzheng, disintegrated. By the early seventeenth century, corruption among palace staff and eunuch overseers had become endemic, further undermining the legitimacy of the throne.

At the same time, Wanli’s retreat reflected a psychological dimension rarely acknowledged in official histories. His early dependence on Zhang Juzheng, followed by years of bureaucratic hostility, left him embittered and isolated. Sources in the Ming Shilu suggest that he increasingly confined himself to private amusements and construction projects, particularly the expansion of his tomb complex, the Dingling Mausoleum, begun in 1584.15 This fixation on his burial site, lavish even by imperial standards, symbolized his withdrawal from temporal responsibility into a realm of self-memorialization. While the court withered in neglect, the emperor devoted attention and resources to his own afterlife, as if substituting immortality for governance. His reign thus mirrored the paradox of many declining dynasties: monumental ambition coexisting with administrative collapse.

Ultimately, the emperor’s inaction was both a symptom and a cause of the Ming dynasty’s weakening structure. By governing through silence, Wanli inverted the traditional relationship between ruler and bureaucracy, turning the imperial voice, a source of unity, into an abyss.16 In doing so, he exposed the fragility of the Ming political order, which relied less on institutions than on the will of a single man. What had begun as a rebellion against bureaucratic intrusion ended as an abdication of imperial responsibility. His protest against moral authority became an abdication of practical authority, leaving an empire suspended between ritual continuity and administrative decay.

Bureaucratic Disintegration and Factionalism

As the Wanli Emperor’s silence deepened, the Ming bureaucracy, long accustomed to direction from the throne, began to fracture under the weight of its own moral pretensions and political inertia. Without imperial adjudication, disputes that might once have been settled by decree now metastasized into full-scale ideological warfare. The absence of a ruling presence transformed the court into an arena of competing factions, each claiming to represent the moral essence of Confucian governance while maneuvering for influence within a collapsing order.17

The most prominent of these factions emerged in the early seventeenth century: the Donglin movement, a coalition of reform-minded scholar-officials centered around the Donglin Academy in Wuxi. Advocating a return to ethical government and fiscal restraint, its members positioned themselves as moral counterweights to corruption within both the bureaucracy and the palace. Yet in the vacuum left by the emperor’s neglect, their moral idealism quickly hardened into dogmatism. Their opponents, often labeled “eunuch sympathizers” or “court opportunists,” accused the Donglin faction of self-righteousness and political obstruction. The rivalry between these camps came to define the late Ming bureaucracy, consuming the energy once devoted to administration.18

Factionalism also flourished because vacancies proliferated across the central ministries. With many posts unfilled for years, informal patronage networks substituted for official hierarchies. Provincial officials sought advancement through private connections rather than merit, while eunuchs and intermediaries exploited their proximity to the throne to sell access.19 The Ministry of Personnel, traditionally responsible for appointments and evaluations, became virtually inoperative, its memorials unanswered and its authority undermined. The resulting breakdown of accountability allowed local corruption to flourish unchecked. Regional tax collectors withheld revenue, military commanders ignored central directives, and magistrates increasingly ruled through personal discretion rather than imperial law.

The intellectual tone of government discourse likewise deteriorated. Bereft of imperial oversight, officials resorted to moral theater as a substitute for effective governance. Public denunciations, impeachment campaigns, and literary polemics became tools of factional identity.20 The so-called moral memorials, long essays excoriating rival officials in the language of virtue, multiplied, often addressing political rivals rather than state affairs. This degeneration of policy into moral performance alienated the populace and eroded faith in bureaucratic competence. As one late Ming chronicler lamented, “They wrote of righteousness while the granaries emptied.”21

Meanwhile, the emperor’s continued refusal to arbitrate these conflicts emboldened palace factions to exploit the chaos. Eunuchs such as Wei Zhongxian, who would later dominate the Tianqi court, rose through the administrative confusion of Wanli’s final years, forming alliances with ministers who traded loyalty for access.22 The distinction between inner and outer court dissolved; bureaucrats who once scorned eunuch interference now found themselves dependent on it to conduct even routine matters. This inversion of the Ming administrative hierarchy, where servants of the palace wielded more practical authority than the ministers of state, represented the culmination of the political decay initiated by imperial silence.

By the time of Wanli’s death in 1620, the bureaucracy he had abandoned no longer functioned as a coherent instrument of governance. What had once been a Confucian meritocracy had devolved into a battlefield of moral posturing, corruption, and factional vendetta.23 The emperor’s withdrawal had stripped the state of its unifying principle, leaving a hollow framework of rituals performed without conviction. In the absence of a governing presence, ideology supplanted administration, and the very qualities that the Confucian bureaucracy prized (virtue, discipline, and hierarchy) became casualties of its own self-righteousness.

The Long Decline: From Stagnation to Collapse

By the early seventeenth century, the cumulative effects of the Wanli Emperor’s long withdrawal had transformed administrative stagnation into imperial decay. The Ming state, once a formidable bureaucratic machine, now functioned only through habit. Fiscal disarray deepened as uncollected taxes and unpaid salaries crippled the treasury. The absence of oversight in the Ministry of Revenue led to chronic deficits, forcing provincial officials to rely on arbitrary levies that alienated local populations.24 At the same time, military preparedness eroded. Garrisons along the northern frontier went unpaid for months, sometimes years, prompting desertions that weakened the defense against the rising power of the Jurchens under Nurhaci. The empire’s vast structure, nominally centralized, had in practice become a federation of isolated provinces held together by inertia.

The emperor’s apathy compounded these crises. When memorials reached the palace warning of frontier instability or famine, they were often left unanswered. The Ming Shilu records multiple occasions in which urgent dispatches regarding Liaodong were ignored entirely.25 By 1618, when Nurhaci launched his campaign against the Ming at Fushun, the court’s paralysis left provincial commanders to act independently, often without coordination or supplies. As military failures mounted, morale collapsed. The emperor’s death two years later found the empire already in decline, its administrative organs weakened beyond repair. His successors inherited not merely a disordered government but a political culture habituated to inertia.

Economic exhaustion intensified this decline. The silver crisis of the early seventeenth century, sparked by fluctuations in global bullion flows, devastated the Single Whip system that had once stabilized Ming finances.26 With silver imports from Japan and Spanish America dwindling, tax collection faltered, and inflation surged. Local officials, unable to remit sufficient revenue to Beijing, resorted to extortion or outright embezzlement to maintain operations. In rural China, peasant uprisings began to spread, fueled by famine and displacement. The Ming state’s fiscal fragility, once mitigated by Zhang Juzheng’s reforms, now re-emerged with renewed force, magnified by decades of bureaucratic neglect.

Equally damaging was the erosion of administrative discipline. The absence of imperial scrutiny had fostered a culture of impunity among officials, where bribery, nepotism, and inefficiency became normalized.27 Inspectors sent to investigate corruption often joined the very networks they were meant to police, knowing that no higher authority would intervene. Even the censors, once the moral conscience of the court, descended into factional self-interest. The Confucian bureaucracy, conceived as a guardian of virtue, had become an engine of self-preservation. The state’s legitimacy, rooted in the moral bond between ruler and minister, dissolved into cynicism and opportunism.

When the Manchus breached the Great Wall in 1644, the Ming dynasty’s collapse appeared sudden, but it was in truth the culmination of this long decline. The seeds of that failure were sown in Wanli’s reign, when governance by silence replaced governance by decree.28 The emperor’s refusal to mediate bureaucratic conflict left the state structurally incapable of responding to crisis. His legacy was not one of tyranny or extravagance, but of abdication, the slow suffocation of a government by inaction. The Wanli era thus stands as a cautionary chapter in the history of imperial governance, a reminder that the absence of decision can be as destructive as despotism itself.

Conclusion: The Politics of Neglect as Historical Warning

The Wanli Emperor’s long withdrawal from governance represents one of the most consequential failures of leadership in the history of imperial China. His silence transformed the Ming political order from a functioning bureaucracy into a hollow ritual apparatus. For nearly thirty years, the mechanisms of state persisted without the animating force of imperial direction, exposing the fragility of a system that depended on personal initiative at its apex. The emperor’s inaction did not merely reflect a loss of will; it redefined the boundaries of autocracy. By refusing to rule, Wanli inverted the logic of Confucian monarchy, demonstrating that absolute power could destroy itself through neglect as effectively as through excess.29

This episode also reveals the deeper paradox of Ming governance: that a system grounded in moral accountability could become paralyzed by its own virtue. The bureaucrats’ relentless moral admonitions, intended to uphold Confucian order, instead provoked the emperor’s retreat. In their insistence on propriety, they mistook moral correction for governance, transforming ethical debate into administrative obstruction. Meanwhile, the emperor’s defiance, initially a bid to reclaim sovereignty from moral constraint, produced the very anarchy he had sought to suppress.30 The resulting stalemate between conscience and authority eroded both, leaving the state directionless. The Wanli reign thus exposes the inherent tension between Confucian orthodoxy and imperial absolutism: a moral state that cannot reconcile principle with power.

The political and cultural consequences of this inertia reverberated far beyond the emperor’s lifetime. The bureaucratic factionalism, fiscal chaos, and public cynicism born of his silence persisted into the Tianqi and Chongzhen reigns, shaping the conditions that allowed the Manchus to conquer China.31 The dynasty’s collapse in 1644 was not an isolated military failure but the culmination of decades of moral exhaustion and administrative decay. In this sense, Wanli’s withdrawal stands as both a cause and a symbol of Ming decline, the moment when the empire’s vast moral architecture ceased to serve its practical purpose. His inaction revealed that ritual and ideology, when severed from responsiveness, become monuments to their own futility.

For historians and political thinkers alike, the Wanli era remains a sobering study in the perils of disengaged authority. Power does not need to be abused to be destructive; it need only be abandoned.32 The emperor’s thirty-year silence demonstrated how governance can perish not in the chaos of rebellion but in the stillness of neglect. In a system where the emperor’s word defined reality, the absence of his word unmade it. The political neglect of the Wanli era thus endures as a timeless warning: that in every age, the refusal to govern is itself a form of rule, and one that exacts the highest possible price.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Ray Huang, 1587: A Year of No Significance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 22–28.

- Ming Shilu (Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty), vols. 494–496 (Taipei: Academia Sinica, 1961).

- Timothy Brook, The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 192–93.

- Charles O. Hucker, The Ming Dynasty: Its Origins and Evolving Institutions (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1978), 155–57.

- John E. Wills, China and Maritime Europe, 1500–1800: Trade, Settlement, Diplomacy, and Missions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 264.

- Huang, 1587, 41.

- John W. Dardess, Confucianism and Autocracy: Professional Elites in the Founding of the Ming Dynasty (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 214–15.

- Ming Shi (History of the Ming), vol. 22 (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1974), 552–53.

- Ming Shilu, 182–83.

- Ming Shilu, 185.

- Huang, 1587, 63–65.

- Ming Shilu, 211–12.

- Huang, 1587, 82.

- Ming Shi, 618–19.

- John E. Wills, The Ming Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 267.

- Brook, The Troubled Empire, 197.

- Dardess, Confucianism and Autocracy, 228–30.

- Brook, The Troubled Empire, 199–200.

- Ming Shi, 644–45.

- Huang, 1587, 87–89.

- Huang, 1587, 90.

- Kenneth M. Swope, The Military Collapse of China’s Ming Dynasty, 1618–1644 (New York: Routledge, 2014), 32–33.

- Wills, The Ming Empire, 269.

- Huang, 1587, 92–94.

- Ming Shilu, 214–15.

- Brook, The Troubled Empire, 205–7.

- Hucker, The Ming Dynasty, 165–66.

- Swope, The Military Collapse of China’s Ming Dynasty, 39–40.

- Dardess, Confucianism and Autocracy, 233.

- Brook, The Troubled Empire, 209.

- Swope, The Military Collapse of China’s Ming Dynasty, 41–43.

- Huang, 1587, 95.

Bibliography

- Brook, Timothy. The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Dardess, John W. Confucianism and Autocracy: Professional Elites in the Founding of the Ming Dynasty. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

- Hucker, Charles O. The Ming Dynasty: Its Origins and Evolving Institutions. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1978.

- Huang, Ray. 1587: A Year of No Significance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

- Ming Shi (History of the Ming). Vols. 22–25. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1974.

- Ming Shilu (Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty). Vols. 494–498. Taipei: Academia Sinica, 1961.

- Swope, Kenneth M. The Military Collapse of China’s Ming Dynasty, 1618–1644. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Wills, John E, et.al. China and Maritime Europe, 1500–1800: Trade, Settlement, Diplomacy, and Missions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.05.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.