When the smoke cleared over the Anacostia Flats, the veterans’ camps lay in ashes, and with them, a piece of the nation’s democratic faith.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The summer heat in Washington, D.C. in 1932 carried with it the weight of despair. Along the muddy flats of the Anacostia River, thousands of men, former soldiers who had fought in the trenches of France, pitched tents and makeshift shacks from scrap wood and tar paper.1 They called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force, a sardonic echo of their wartime title, the American Expeditionary Force. Their mission, this time, was not to battle a foreign enemy but to appeal to their own government for the payment of bonuses they had been promised years earlier for their service in World War I.2 The Great Depression had emptied their pockets and their prospects; they came to the capital seeking not charity, but compensation they believed they had earned.

The sight of veterans, many wearing remnants of old uniforms, marching down Pennsylvania Avenue unsettled a nation already reeling from unemployment and foreclosures.3 Some carried flags and placards; others brought their families, children trailing behind in wagons. Newspapers alternated between sympathy and suspicion, describing them as both patriots and agitators. As the encampment swelled into the tens of thousands, President Herbert Hoover found himself trapped between public compassion for the veterans and fear of unrest. In this uneasy balance between authority and empathy, the seeds of confrontation were sown.

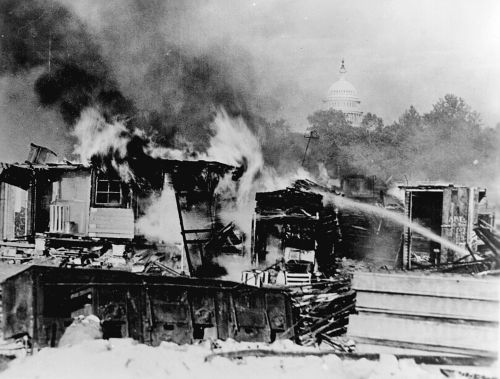

When the inevitable clash came in late July, it was not the result of coordinated insurrection, but of misunderstanding, arrogance, and defiance.4 General Douglas MacArthur, convinced that the encampment threatened national stability, ordered U.S. Army troops to clear the city by force. Cavalry, infantry, and even tanks rolled through Washington’s streets. Fires lit the night sky as veterans and their families fled the smoldering ruins of their camps. Hoover’s explicit orders to limit the operation went unheeded, a moment that revealed the fragility of civilian control over the military during crisis.5

The violence in Washington shocked the nation. What began as a peaceful protest ended as a spectacle of bayonets and smoke against those who had once worn the uniform themselves. The Bonus Army episode became both a tragedy of economic desperation and a warning about the misuse of power. It would shadow Hoover into the November election, reinforcing his image as aloof and heartless in the face of suffering. More deeply, it exposed a structural fault in American democracy: how easily the line between lawful authority and unlawful force can blur when the instruments of government turn against their own citizens.

Background: The Bonus Certificates and the Great Depression

The origins of the Bonus Army trace back to the postwar politics of gratitude and neglect that followed World War I. In 1924, after years of debate and vetoes, Congress passed the World War Adjusted Compensation Act over President Calvin Coolidge’s objections.6 The law granted veterans “adjusted service certificates” that promised a cash payment based on the length and location of their service, but the money would not be redeemable until 1945, more than two decades after the war’s end.7 For many, these certificates were a symbolic recognition of sacrifice rather than practical compensation. They were to mature with interest, theoretically yielding a modest sum at midlife, but they held little immediate value during the prosperity of the 1920s.

The Wall Street crash of 1929 transformed those pieces of paper into a lifeline that could not be reached. By 1932, unemployment among veterans had soared to nearly 25 percent, with many men unable to feed their families.8 Soup lines replaced steady pay, and homes were lost to foreclosure. The veterans’ organizations that had once focused on commemoration turned instead toward survival. The idea of redeeming the bonus early gained traction, especially among those who argued that the federal government had rewarded bankers and corporations with relief while neglecting those who had once borne arms for the nation.9 “The bonus,” one veteran told a congressional committee that spring, “is not charity; it is our due.”10

The movement to demand early payment coalesced under the leadership of Walter W. Waters, a former Army sergeant from Oregon.11 In May 1932, Waters and a small group of jobless veterans set out for Washington, D.C., traveling atop freight trains and hitching rides across the country. Newspapers dubbed them the “Bonus Expeditionary Force,” a sardonic twist on the American Expeditionary Force that had fought in France.12 As they moved eastward, thousands joined, some carrying tattered flags, others accompanied by wives and children. By June, more than fifteen thousand veterans had gathered in the capital, determined to press Congress for immediate redemption of their certificates.13

Their cause reached the House of Representatives, where a bill sponsored by Congressman Wright Patman of Texas proposed payment of the bonuses at once. The measure passed the House on June 15, 1932, by a narrow margin, but it was defeated two days later in the Senate.14 The rejection hit the encampments like a hammer blow. Many veterans remained in Washington despite official calls to disperse, camping in abandoned buildings downtown and along the Anacostia Flats. They maintained order through elected committees, banned alcohol, and even established a newspaper, The B.E.F. News, to communicate updates.15 Their conduct defied the stereotypes of disorder that opponents circulated, reinforcing that their protest was not insurrection but endurance born of hunger and betrayal.

The federal government faced a dilemma: the protest was lawful, yet it challenged authority merely by existing. The veterans’ presence embarrassed Hoover’s administration, which saw the encampment as a symbol of national failure and a potential flashpoint for unrest.16 In the summer’s oppressive heat, as tensions built between police, residents, and the encamped veterans, the stage was set for confrontation.

The March on Washington and the Encampment

By the time the first contingents of veterans reached Washington in late May 1932, the city was unprepared for what would follow.17 The Bonus Expeditionary Force (BEF) arrived not as an organized army but as a vast procession of individuals (unemployed laborers, fathers, amputees, widows, and children) drawn together by desperation and the shared conviction that the government had broken faith with them.18 They slept in rail yards, parks, and abandoned buildings. The District of Columbia police, under Chief Pelham D. Glassford, a former Army brigadier general sympathetic to the veterans, initially tolerated their presence and helped them find shelter on the Anacostia Flats across the river.19 Glassford arranged for food distribution and sanitation, turning a potential crisis into what one reporter called “a city of the forgotten, built on discipline and dignity.”20

The encampment grew rapidly, spreading over the lowlands near the Eleventh Street Bridge. Rows of shacks and tents lined the riverbank, while handmade signs proclaimed loyalty to the nation: “Don’t We Deserve Justice?” and “Veterans Still on Duty.”21 The veterans established elected councils, issued identification cards, and enforced strict rules against drinking and disorder. Their organization surprised observers who expected chaos.22 Black and white veterans lived side by side in a rare instance of interracial solidarity during the Depression, defying segregationist norms of the era.23 In their self-governance and restraint, the BEF reflected both military discipline and democratic aspiration, the conviction that protest itself was a form of service.

Public sympathy for the marchers ran high. Newspapers chronicled their daily routines and hardship, and civic groups donated supplies.24 Photographs of veterans saluting the flag before makeshift shelters circulated nationwide, capturing the moral contrast between their poverty and the government’s indifference. Yet not all coverage was charitable. Some conservative papers labeled the veterans “radicals” or “communists,” feeding Hoover’s growing anxiety that the demonstration might spiral into disorder.25 Still, the veterans’ leaders insisted on lawful conduct and repeatedly emphasized their loyalty to the United States. Walter Waters, addressing a crowd from the steps of the Capitol, declared, “We are here to demand what was promised, not to destroy, but to redeem.”26

Congressional debate over the Patman Bill intensified as the BEF maintained its vigil. When the House narrowly passed the measure on June 15, cheers erupted across Anacostia Flats.27 The victory proved short-lived. Two days later, the Senate rejected the bill by a margin of 62 to 18, prompting scenes of anguish and disbelief in the encampment. Many veterans had spent their last savings reaching Washington and refused to leave empty-handed.28 Glassford again intervened, persuading city officials to allow the camps to remain temporarily. He described the veterans as “orderly, patient, and patriotic,” warning that a forced eviction could ignite violence.29 Hoover, though uneasy, agreed, for the moment, to let them stay.

The weeks that followed tested that uneasy truce. Summer heat turned the shantytown into a mire of dust and mosquitoes. Food grew scarce, and tensions with local authorities mounted.30 A few minor clashes occurred between veterans and police, largely over access to abandoned federal buildings used for shelter. The press exaggerated these incidents into rumors of uprising.31 In late July, when Congress adjourned without revisiting the bill, the federal government declared the veterans’ continued occupation unlawful. Hoover ordered that the remaining protesters be removed from federal property, but explicitly directed that no force be used against the main camp across the river.32 It was an order that would soon be ignored.

In the early morning of July 28, a confrontation broke out when police attempted to evict a small group of veterans from a warehouse near Pennsylvania Avenue. Stones were thrown, shots were fired, and two veterans were killed.33 The incident triggered panic and outrage within the camps. Within hours, Douglas MacArthur, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, mobilized infantry, cavalry, and tanks under Major George S. Patton.34 Hoover’s instructions to limit the operation to federal property never reached, or were disregarded by, the general. The spectacle that followed would forever scar the nation’s memory of the Great Depression: American soldiers advancing with bayonets and tear gas against unarmed veterans.

The Government Response and the Military Intervention

The clash of July 28, 1932, began in confusion and ended in tragedy.35 When two veterans were killed in a skirmish with local police at a downtown warehouse, Washington erupted in chaos.36 Rumors spread that armed radicals were preparing to march on the White House. President Herbert Hoover, already wary of being seen as indifferent to suffering, ordered Secretary of War Patrick Hurley to clear federal buildings but instructed explicitly that “no troops are to cross the bridge” into the Anacostia Flats encampment.37 Those orders, according to several eyewitness and military accounts, never reached, or were deliberately ignored by, General Douglas MacArthur.38

MacArthur viewed the Bonus Army as a revolutionary threat, not a group of destitute veterans. He later claimed to have believed that “a Communist element” had infiltrated the camps and that swift military action was required to preserve public order.39 By early evening, infantry and cavalry units had assembled under MacArthur’s personal command, joined by six tanks led by Major George S. Patton.40 Crowds of bystanders lined Pennsylvania Avenue as the troops advanced, brandishing rifles with fixed bayonets and releasing tear gas into the smoke-choked streets.41 Hoover remained in the White House, receiving fragmented reports as the operation unfolded far beyond the limited action he had authorized.42

By nightfall, the soldiers had driven thousands of veterans and their families from downtown Washington across the Eleventh Street Bridge. Fires from the Anacostia Flats camp illuminated the sky as troops torched the shacks and tents that had housed entire families.43 Photographers captured haunting images of veterans clutching their children as clouds of gas drifted over the river.44 Two infants died from exposure in the following days, and hundreds were injured or arrested.45 In a chilling moment that underscored the collapse of civilian command, MacArthur defied a second direct order from the White House to halt the operation and instead pressed forward, declaring the removal “a necessary act of national defense.”46

Public outrage was immediate and widespread. Newspapers that had once supported Hoover condemned the spectacle. The New York Times called it “a pitiful episode in the story of America’s forgotten men,” while the Washington Post lamented “the tragedy of brothers-in-arms turned upon each other.”47 Within days, editorials across the nation decried the government’s use of military force against its own veterans. The administration attempted to portray the operation as a restoration of order, but few were persuaded.48 The image of soldiers advancing with bayonets against unarmed men who had fought under the same flag struck a deep moral chord. For many Americans, it became the defining symbol of a government that had lost both compassion and control.

In the weeks that followed, Hoover refused to dismiss MacArthur, insisting that he had acted in good faith despite exceeding instructions.49 The decision alienated both moderates and conservatives, many of whom viewed the general’s defiance as a direct affront to civilian authority.50 The rift between the president and his military commander laid bare a constitutional fault line: the subordination of the military to elected leadership.51 While the legal framework of civilian control remained intact, the Bonus Army crisis revealed how fragile that principle could become in moments of fear and uncertainty. Hoover’s failure to reassert command not only damaged his presidency but also set a dangerous precedent for the autonomy of military power in domestic affairs.52

The Political Fallout and Election of 1932

The images of the Bonus Army’s destruction spread rapidly through newspapers, newsreels, and word of mouth, turning what had been a domestic policy dispute into a moral reckoning.53 Public sympathy overwhelmingly favored the veterans, whose ragged camps and burned belongings now symbolized the administration’s callousness. Within a week, The Washington Post received thousands of letters condemning the government’s actions, while veterans’ organizations across the country demanded investigations.54 The White House, already burdened by record unemployment and financial collapse, now faced a crisis of legitimacy. Hoover’s effort to defend his administration’s role, arguing that “law and order” had to be preserved, only deepened public resentment.55 To many Americans, the spectacle of uniformed soldiers attacking unarmed veterans rendered the phrase grotesque.

The Democratic Party seized upon the tragedy as evidence of a government estranged from its people. Franklin D. Roosevelt, then the governor of New York and the Democratic nominee for president, declined to exploit the event directly but quietly contrasted his message of “relief, recovery, and reform” with the Hoover administration’s reliance on force.56 Behind the scenes, party strategists circulated photographs of the burning encampment to highlight Hoover’s failure of compassion.57 Even members of Hoover’s own Republican Party distanced themselves. Senator Hiram Johnson of California condemned the operation as “a shameful and unnecessary use of military power against those who once defended the Republic.”58

In Congress, investigations into the use of the Army were brief but revealing. Witnesses, including Chief of Police Pelham Glassford, testified that the veterans had remained largely peaceful and that MacArthur’s advance went beyond the scope of presidential orders.59 The hearings never produced formal censure, but they exposed the dissonance between civilian command and military obedience at the highest levels. The War Department defended MacArthur’s decision as a “restoration of order,” while Hoover’s inner circle privately lamented that the general’s defiance had cost the administration whatever moral authority it retained.60 By autumn, the phrase “Bonus Army” had become shorthand for both the despair of the Great Depression and the failure of leadership that allowed tragedy to unfold.

In the November election, Hoover’s defeat was decisive.61 Roosevelt carried forty-two of forty-eight states, a landslide fueled as much by economic desperation as by disillusionment with the incumbent’s response to human suffering. Although no single event determined the outcome, contemporary observers and later historians consistently cited the Bonus Army episode as a key factor in eroding public confidence.62 The violence in Washington had become the administration’s moral epitaph: a government willing to turn its army inward against its own citizens. In Roosevelt’s inaugural address the following March, his assurance that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself” resonated partly because Americans had seen how fear (of disorder, of weakness, of compassion) had undone his predecessor.63

The legacy of the Bonus Army did not end with Hoover’s political demise. Four years later, in 1936, Congress overrode Roosevelt’s veto to authorize immediate payment of the veterans’ bonuses, acknowledging belatedly the justice of their demands.64 Yet the wounds of 1932 lingered. For veterans who had survived the tear gas and bayonets, the government’s eventual concession offered little solace.65 The tragedy at Anacostia Flats had revealed something deeper than policy failure: it exposed the fragility of democratic trust when the state forgets its obligation to those who once defended it.

Evaluation: Power, Protest, and Democracy

The Bonus Army protest remains one of the clearest moral tests of American democracy during the Great Depression.66 It was not merely a conflict over money but a confrontation between two visions of citizenship: one rooted in reciprocal obligation and another in administrative order. The veterans had come as petitioners invoking the social contract they believed they had upheld through service. The government, fearing disorder more than despair, responded as if the exercise of democratic petition itself posed a threat to the state.67 That inversion, where loyalty was mistaken for subversion, defined the tragedy of 1932.

The crisis also revealed the fragility of civilian control over the military, a cornerstone of American constitutional government.68 Hoover’s inability or unwillingness to rein in General MacArthur exposed how military autonomy could expand in moments of perceived emergency. MacArthur’s decision to exceed direct orders not only violated the president’s command but also undermined the very principle that separates democracy from military rule.69 As later historians have noted, the event stands as a precursor to later episodes in which force supplanted judgment, from the Kent State shootings in 1970 to the militarization of domestic policing in the twenty-first century.70 Each reflects the same underlying tension between security and liberty that haunted the Anacostia Flats.

At its core, the Bonus Army episode illuminates how governments respond when the marginalized demand recognition.71 The veterans were not revolutionaries; they were citizens asserting rights promised by law. Yet the state interpreted their encampment as an existential challenge, transforming social grievance into political threat. The episode demonstrated that democratic institutions are tested not by enemies abroad but by the cries of the dispossessed at home.72 In burning the camps, the government destroyed more than shanties; it eroded the symbolic trust between citizen and state that underpins the legitimacy of governance.

The tragedy also transformed American political culture. Roosevelt’s subsequent approach to veterans, and to public protest generally, contrasted sharply with Hoover’s.73 While FDR did not endorse the 1932 demands, his administration recognized the power of perception and the necessity of empathy in leadership. The New Deal programs that followed (the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Works Progress Administration, and others) embodied lessons drawn from the moral failure of the Bonus March: that democracy must address suffering before it becomes revolt.74 In this sense, the veterans’ defeat was not in vain. Their march forced the nation to confront the human cost of policy abstraction.

In the broader sweep of history, the Bonus Army stands as both a warning and a mirror. It warns that even the most stable republic can falter when fear overrides compassion and that the instruments of defense can become tools of repression when accountability fades.75 It mirrors recurring patterns in American life: protest, suppression, and eventual reform. Every generation inherits the question posed by the veterans on the Anacostia Flats, how far will a democracy go to silence those who remind it of its promises?76 The answer, as 1932 revealed, depends less on law than on conscience.

Conclusion

When the smoke cleared over the Anacostia Flats, the veterans’ camps lay in ashes, and with them, a piece of the nation’s democratic faith.77 The Bonus Army had come to Washington not as a mob, but as a mirror, reflecting a country that had promised prosperity and delivered destitution. In their march, the veterans asked a simple question: would the republic honor those who had honored it? The government’s answer, given through bayonets and tear gas, revealed a deeper truth about fear and authority in hard times. Hoover’s administration, confronted with poverty and unrest, mistook loyalty for rebellion and order for justice.78

In retrospect, the events of 1932 mark a pivotal test of the American experiment. The veterans’ expulsion was not only a humanitarian disaster but also a constitutional warning. Civilian control over the military, the foundation of republican government, proved alarmingly porous when challenged by internal crisis.79 The defiance of General Douglas MacArthur, acting beyond the lawful command of the president, exposed how quickly power could shift from elected authority to autonomous force. Later generations would recall that night in Washington as a case study in the peril of unchecked command, one that remains instructive in every age where the boundary between public safety and civil liberty grows thin.80

Yet, the Bonus Army’s defeat was not the end of their story. Four years later, Congress finally approved early payment of the bonuses they had sought, a symbolic redemption that came too late for many.81 The veterans’ suffering, immortalized in photographs and testimony, altered public consciousness. It transformed how the nation viewed protest, not as sedition but as a plea for justice. Their stand reshaped the moral vocabulary of American citizenship, reminding future generations that the right to petition one’s government is not conditional upon comfort or approval.82

Ultimately, the legacy of the Bonus Army endures less in the burned fields of Anacostia than in the enduring principle it affirmed: that democracy must be judged by how it treats the powerless, not the privileged.83 The men who marched on Washington in 1932 carried no weapons, only the weight of broken promises. Their courage outlived their defeat. In their silence after the smoke, one hears the echo of a timeless demand, that the government of the people must also be a government for them.84

Appendix

Footnotes

- National Archives, “The Bonus Army: An American Epic,” Records of the U.S. Army, 1932.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching,” accessed November 2025.

- New York Times, “Bonus Army Marches into Washington,” May 24, 1932.

- National Archives, “Eyewitness Accounts of the 1932 Bonus March,” Records of the U.S. War Department.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History, “The Bonus March: Douglas MacArthur and the 1932 Protests,” accessed November 2025.

- Congressional Record, 68th Congress, 1st Session (May 19, 1924), 9245–9247.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, “History of the World War Adjusted Compensation Act of 1924,” accessed November 2025.

- New York Times, “Unemployment Among War Veterans Reaches Crisis,” March 3, 1932.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching,” accessed November 2025.

- U.S. Senate, Hearings Before the Committee on Finance on the Adjusted Compensation Payment Bill (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1932), 47.

- National Archives, “The Bonus Army: An American Epic,” Records of the U.S. Army, 1932.

- Washington Post, “Veterans Form ‘Bonus Expeditionary Force,’” May 27, 1932.

- National Archives, “Eyewitness Accounts of the 1932 Bonus March,” Records of the U.S. War Department.

- Congressional Record, 72nd Congress, 1st Session (June 17, 1932), 13102–13105.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History, “The Bonus March: Douglas MacArthur and the 1932 Protests,” accessed November 2025.

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, “The Bonus March, 1932,” accessed November 2025.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching,” accessed November 2025.

- National Archives, “Eyewitness Accounts of the 1932 Bonus March,” Records of the U.S. War Department.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History, “The Bonus March: Douglas MacArthur and the 1932 Protests,” accessed November 2025.

- Washington Post, “Glassford Guides Veterans’ Camp to Order,” June 6, 1932.

- New York Times, “Veterans’ City Rises on the Anacostia Flats,” June 10, 1932.

- National Archives, “The Bonus Army: An American Epic,” Records of the U.S. Army, 1932.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching.”

- New York Times, “Public Sends Aid to Bonus Marchers,” June 20, 1932.

- Chicago Tribune, “Reds in the Bonus Army? Administration Fears Plot,” June 24, 1932.

- U.S. Senate, Hearings Before the Committee on Finance on the Adjusted Compensation Payment Bill (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1932), 83.

- Congressional Record, 72nd Congress, 1st Session (June 17, 1932), 13102–13105.

- National Archives, “Eyewitness Accounts of the 1932 Bonus March.”

- Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, “The Bonus March, 1932,” accessed November 2025.

- Washington Post, “Bonus Camp Battles Heat, Hunger,” July 12, 1932.

- New York Times, “Bonus Army Rumors Stir Fear in Capital,” July 18, 1932.

- Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, “The Bonus March, 1932.”

- Washington Post, “Two Veterans Killed in Clash with Police,” July 28, 1932.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History, “The Bonus March: Douglas MacArthur and the 1932 Protests.”

- Washington Post, “Two Veterans Killed in Clash with Police,” July 28, 1932.

- National Archives, “Eyewitness Accounts of the 1932 Bonus March,” Records of the U.S. War Department.

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, “The Bonus March, 1932,” accessed November 2025.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History, “The Bonus March: Douglas MacArthur and the 1932 Protests,” accessed November 2025.

- Douglas MacArthur, Reminiscences (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), 123–125.

- New York Times, “Army Mobilized to Oust Bonus Marchers,” July 28, 1932.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching,” accessed November 2025.

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, “The Bonus March, 1932.”

- New York Times, “Veterans’ Camp in Flames After Army Attack,” July 29, 1932.

- National Archives, “Eyewitness Accounts of the 1932 Bonus March.”

- Washington Post, “Infants Die Following Bonus March Eviction,” August 1, 1932.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History, “The Bonus March: Douglas MacArthur and the 1932 Protests.”

- New York Times, editorial, “The Forgotten Men,” July 30, 1932; Washington Post, “An American Tragedy,” July 31, 1932.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching.”

- Herbert Hoover, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Herbert Hoover, 1932 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1933), 487.

- Chicago Tribune, “Hoover Defends MacArthur’s Action,” August 2, 1932.

- National Archives, “The Bonus Army: An American Epic,” Records of the U.S. Army, 1932.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History, “The Bonus March: Douglas MacArthur and the 1932 Protests.”

- New York Times, “Nation Shocked by Army’s Action Against Veterans,” July 30, 1932.

- Washington Post, “Letters Denounce Bonus March Suppression,” August 3, 1932.

- Herbert Hoover, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Herbert Hoover, 1932 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1933), 492.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, “Campaign Correspondence, 1932: Response to the Bonus Army Incident,” accessed November 2025.

- Chicago Tribune, “Democrats Cite Bonus March as Symbol of Hoover’s Failure,” August 10, 1932.

- New York Times, “Senator Johnson Calls Army Action a Shameful Blot,” August 2, 1932.

- U.S. Congress, Hearings Before the House Committee on Military Affairs on the Use of the Army in Washington, D.C., 72nd Cong., 2nd sess. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1932), 11–16.

- National Archives, “The Bonus Army: An American Epic,” Records of the U.S. Army, 1932.

- New York Times, “Election Results, 1932,” November 9, 1932.

- David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 102–103.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, “First Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1933, in Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, vol. 2 (New York: Random House, 1938), 12.

- Congressional Record, 74th Congress, 2nd Session (January 27, 1936), 8989–8993.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching,” accessed November 2025.

- William Pencak, For God and Country: The American Legion, 1919–1941 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1989), 212–213.

- New York Times, “Nation Shocked by Army’s Action Against Veterans,” July 30, 1932.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History, “The Bonus March: Douglas MacArthur and the 1932 Protests,” accessed November 2025.

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, “The Bonus March, 1932,” accessed November 2025.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 104.

- National Archives, “The Bonus Army: An American Epic,” Records of the U.S. Army, 1932.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching,” accessed November 2025.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, “FDR and the Veterans: Policy Shifts After the Bonus March,” accessed November 2025.

- Kenneth S. Davis, FDR: The New Deal Years, 1933–1937 (New York: Random House, 1986), 56–57.

- U.S. Senate Historical Office, “Civil-Military Relations in American History,” accessed November 2025.

- New York Times, “The Forgotten Men,” editorial, July 30, 1932.

- National Archives, “Eyewitness Accounts of the 1932 Bonus March,” Records of the U.S. War Department.

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, “The Bonus March, 1932,” accessed November 2025.

- U.S. Senate Historical Office, “Civil-Military Relations in American History,” accessed November 2025.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 106–107.

- Congressional Record, 74th Congress, 2nd Session (January 27, 1936), 8989–8993.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching,” accessed November 2025.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, “FDR and the Veterans: Policy Shifts After the Bonus March,” accessed November 2025.

- New York Times, “The Forgotten Men,” editorial, July 30, 1932.

Bibliography

- Books and Scholarly Works

- Davis, Kenneth S. FDR: The New Deal Years, 1933–1937. New York: Random House, 1986.

- Hoover, Herbert. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Herbert Hoover, 1932. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1933.

- Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- MacArthur, Douglas. Reminiscences. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964.

- Pencak, William. For God and Country: The American Legion, 1919–1941. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1989.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Vol. 2. New York: Random House, 1938.

- Government Documents and Congressional Records

- Congressional Record. 68th Congress, 1st Session (May 19, 1924), 9245–9247.

- Congressional Record. 72nd Congress, 1st Session (June 17, 1932), 13102–13105.

- Congressional Record. 74th Congress, 2nd Session (January 27, 1936), 8989–8993.

- U.S. Congress. Hearings Before the House Committee on Military Affairs on the Use of the Army in Washington, D.C. 72nd Cong., 2nd sess. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1932.

- U.S. Senate. Hearings Before the Committee on Finance on the Adjusted Compensation Payment Bill. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1932.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. “History of the World War Adjusted Compensation Act of 1924.” Accessed November 2025.

- U.S. Senate Historical Office. “Civil-Military Relations in American History.” Accessed November 2025.

- Archival and Institutional Sources

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. “Campaign Correspondence, 1932: Response to the Bonus Army Incident.” Accessed November 2025.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. “FDR and the Veterans: Policy Shifts After the Bonus March.” Accessed November 2025.

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. “The Bonus March, 1932.” Accessed November 2025.

- National Archives. “The Bonus Army: An American Epic.” Records of the U.S. Army, 1932.

- National Archives. “Eyewitness Accounts of the 1932 Bonus March.” Records of the U.S. War Department.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History. “The Bonus March: Douglas MacArthur and the 1932 Protests.” Accessed November 2025.

- Newspapers and Periodicals

- Chicago Tribune. “Democrats Cite Bonus March as Symbol of Hoover’s Failure.” August 10, 1932.

- Chicago Tribune. “Hoover Defends MacArthur’s Action.” August 2, 1932.

- Chicago Tribune. “Reds in the Bonus Army? Administration Fears Plot.” June 24, 1932.

- New York Times. “Army Mobilized to Oust Bonus Marchers.” July 28, 1932.

- New York Times. “Bonus Army Marches into Washington.” May 24, 1932.

- New York Times. “Bonus Army Rumors Stir Fear in Capital.” July 18, 1932.

- New York Times. “Election Results, 1932.” November 9, 1932.

- New York Times. “Nation Shocked by Army’s Action Against Veterans.” July 30, 1932.

- New York Times. “Senator Johnson Calls Army Action a Shameful Blot.” August 2, 1932.

- New York Times. “Unemployment Among War Veterans Reaches Crisis.” March 3, 1932.

- New York Times. “Veterans’ Camp in Flames After Army Attack.” July 29, 1932.

- New York Times. “Veterans’ City Rises on the Anacostia Flats.” June 10, 1932.

- New York Times. “The Forgotten Men.” Editorial. July 30, 1932.

- Smithsonian Magazine. “When the Veterans Came Marching Home—and Kept Marching.” Accessed November 2025.

- Washington Post. “An American Tragedy.” July 31, 1932.

- Washington Post. “Bonus Camp Battles Heat, Hunger.” July 12, 1932.

- Washington Post. “Glassford Guides Veterans’ Camp to Order.” June 6, 1932.

- Washington Post. “Infants Die Following Bonus March Eviction.” August 1, 1932.

- Washington Post. “Letters Denounce Bonus March Suppression.” August 3, 1932.

- Washington Post. “Two Veterans Killed in Clash with Police.” July 28, 1932.

- Washington Post. “Veterans Form ‘Bonus Expeditionary Force.’” May 27, 1932.

- Washington Post. “Public Sends Aid to Bonus Marchers.” June 20, 1932.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.11.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.