In Indian memory, Mir Jafar’s name became synonymous with treachery. To call someone a “Mir Jafar” was to brand them a traitor to their people.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In June 1757, on the plains near the village of Plassey, the destiny of India turned on an act of betrayal. Mir Jafar, commander of the Bengal army under Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah, was among the most trusted generals in the nawab’s service. Yet in the decisive moment of battle, his forces stood still while the British East India Company, led by Robert Clive, engaged a numerically superior Bengal army. The battle lasted only a few hours. Its outcome was determined less by gunfire than by treachery. When the smoke cleared, Siraj had fled, the Company had triumphed, and Mir Jafar was proclaimed the new Nawab of Bengal. What appeared to be a local coup in the struggle for a provincial throne was, in reality, the beginning of an empire.1

Bengal in the mid-eighteenth century was not a remote frontier but one of the richest provinces in the world. Its riverine plains produced silk, cotton, saltpeter, and grain in quantities that drew merchants from every continent. The Mughal Empire, though weakening, still sustained a vast economy centered on Bengal’s ports. Siraj-ud-Daulah, the young successor to his grandfather Alivardi Khan, inherited both this wealth and its burdens: European trading powers who fortified their settlements, local nobles vying for autonomy, and court factions hungry for influence. Among these factions, none was more dangerous than the one within his own army. Mir Jafar, passed over for higher honors and alienated by the nawab’s erratic temper, became the focus of discontent.2

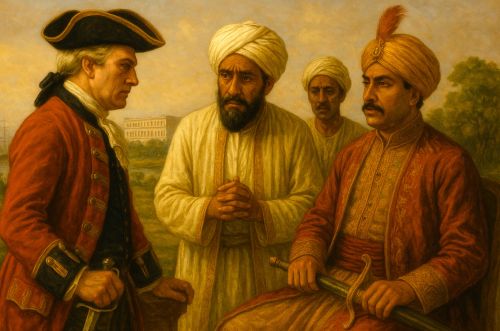

The East India Company, still a mercantile body chartered for trade rather than conquest, recognized in Bengal’s divisions an opportunity for dominion. Company officials, especially Robert Clive and William Watts, exploited personal grievances to engineer regime change. The correspondence between Clive and Mir Jafar reveals a calculated strategy: promises of wealth and power in exchange for betrayal.3 In Mir Jafar’s hands, political ambition became a weapon against his own sovereign, while in the Company’s, bribery became an instrument of empire. The Battle of Plassey was thus less a military encounter than a corporate acquisition, a conquest achieved by contract before it was confirmed by cannon.

Mir Jafar’s triumph proved to be his undoing. Once installed as Nawab, he discovered that sovereignty had passed irretrievably to his British patrons. The vast indemnities demanded by the Company drained the Bengal treasury, while the control of trade and taxation shifted into foreign hands. Within a decade, Bengal’s autonomy had collapsed entirely; by 1765, the diwani, the right to collect revenue, was formally granted to the Company by the Mughal emperor.4 The betrayal that won Mir Jafar a throne condemned his province to two centuries of colonial subjugation. The wealth that once sustained Bengal’s prosperity now financed Britain’s industrial revolution, leaving behind famine, impoverishment, and the dismemberment of Indian sovereignty.

The story of Mir Jafar is therefore not merely a tale of personal treason but of structural transformation. It marks the moment when private enterprise became political authority, and when collaboration replaced conquest as the mechanism of imperial expansion. The betrayal at Plassey was neither an accident nor an anomaly; it was the prototype of a new imperial order in which commerce, corruption, and coercion were inseparable. What follows will trace the political and economic context that made such betrayal possible, the events of the conspiracy itself, and the enduring consequences of Mir Jafar’s alliance with the East India Company. In doing so, it will reveal how one man’s ambition became the opening act in the long tragedy of colonial rule in India.5

Bengal before Plassey: Wealth, Power, and Internal Division

On the eve of the Battle of Plassey, Bengal stood as the crown jewel of the late Mughal world, a province whose prosperity inspired envy across continents. The fertile Gangetic delta yielded more than any other region of Asia, sustaining the global textile trade that clothed Europe and enriched Mughal coffers. Its capital, Murshidabad, rivaled London and Paris in opulence, its markets overflowing with silk, muslin, sugar, and saltpeter. Beneath this glittering economy, however, the political foundations of Bengal had begun to erode. The empire that once held its governors in check was crumbling, and ambitious men at the provincial level now wielded power with near-royal autonomy. The British East India Company, nominally a trading partner, watched these shifts with opportunistic patience.6

The death of Alivardi Khan in 1756 ended a long reign of relative stability. His successor, Siraj-ud-Daulah, was barely twenty-three, youthful, impetuous, and distrusted by many of his nobles. He inherited not only immense wealth but deep resentment among the landed aristocracy and military elite who had prospered under his grandfather’s patronage. Among these was Mir Jafar, who had served faithfully as Bakshi, the paymaster-general of the army. Passed over for promotion and humiliated by the nawab’s erratic behavior, he found his loyalty tested. Contemporary accounts suggest that Siraj’s suspicion of his officers, often bordering on paranoia, fostered the very treachery he feared.7

Meanwhile, the East India Company’s ambitions were no longer confined to trade. Its fortified settlement at Calcutta had become a symbol of European arrogance, and the unauthorized expansion of defenses along the Hooghly River violated the nawab’s sovereignty. When Siraj moved to suppress these intrusions, seizing the British factory at Kasimbazar and capturing Calcutta, he acted within his rights as ruler of Bengal. But the British response, led by Robert Clive and Admiral Charles Watson, was far from commercial diplomacy. The recapture of Calcutta in January 1757 signaled a new kind of war: one in which trade disputes became pretexts for political takeover.8

Beneath these open conflicts lay a web of private correspondence and bribery that prepared the ground for betrayal. British merchants and Company agents sought alliances among the discontented courtiers of Murshidabad. Jagat Seth, the banker whose financial networks spanned Bengal and the Deccan, feared Siraj’s unpredictability and joined the plot that would soon reshape the subcontinent. It was under these circumstances that Mir Jafar emerged as the indispensable conspirator, the general whose cooperation could deliver victory without battle.9 His disaffection, once a personal grievance, became the linchpin of imperial design.

Bengal’s wealth, then, was both its glory and its curse. The very affluence that made it the envy of the world rendered it vulnerable to the predations of mercantile empire. The nawab’s court, consumed by factional jealousy, failed to see that its internal rivalries were being manipulated by forces whose goals extended far beyond Bengal’s borders. As Sushil Chaudhury has noted, the East India Company’s strategy depended not on overwhelming strength but on “the exploitation of division and the purchase of allegiance.”10 By the time the monsoon clouds gathered over Plassey, the fate of Bengal had already been sealed, not by armies in the field, but by signatures on secret agreements and letters written in the dim light of Murshidabad’s palaces.

The Conspiracy: Alliance Between Mir Jafar and the Company

The conspiracy that brought down Siraj-ud-Daulah was not born on the battlefield but in correspondence, secrecy, and calculated deceit. The East India Company, reeling from its losses in Calcutta and hungry for both retribution and dominion, realized that Bengal could not be conquered by force alone. It could, however, be purchased. Robert Clive, newly restored to command after his campaigns in South India, combined audacity with corporate pragmatism. His letters to the Company’s directors reveal a plan that relied less on military genius than on the corruption of Bengal’s ruling elite.11 He understood that discontent within the nawab’s court was as potent a weapon as the artillery he lacked.

Mir Jafar’s recruitment was orchestrated through intermediaries such as William Watts, the Company’s political agent in Murshidabad. Watts cultivated contact with the Jagat Seth banking house, whose patriarch, Mahtab Rai, was among the most influential financiers in Bengal. The Jagat Seths had grown wary of Siraj’s temper and feared confiscation of their wealth. Their cooperation was decisive. They offered both money and credibility to the British plan, promising to secure internal allies in exchange for guarantees of protection and trade privileges once the regime changed.12 The network widened to include Rai Durlabh and Omichund, courtiers motivated by a blend of fear, greed, and ambition. By early 1757, a written agreement had been drafted between Clive and the conspirators, naming Mir Jafar as the Company’s chosen successor.

This compact was explicit: if the British defeated Siraj-ud-Daulah, Mir Jafar would be installed as Nawab, pay the Company a massive indemnity, and cede key territories and trade rights. The total sum promised in cash and goods exceeded 15 million rupees, a staggering figure, enough to bankrupt any treasury but irresistible to those who viewed empire as an extension of commerce.13 In exchange, the Company pledged to restore order and maintain Bengal’s sovereignty under its “protection,” a euphemism that would soon prove meaningless. The signatures may have been written in ink, but they carried the weight of iron chains that would bind Bengal for generations.

Omichund’s role in the conspiracy introduced a layer of infamy to an already sordid affair. A wealthy merchant with connections to both sides, he attempted to demand a personal commission for his services, threatening to expose the plot unless his conditions were met. Clive’s response revealed the moral bankruptcy of imperial politics. To deceive Omichund, he ordered two treaties to be drafted (one genuine, one false) the latter including Omichund’s promised reward, while the former, signed by all parties, omitted it entirely.14 When the deception was later exposed, even Clive’s contemporaries recoiled at the duplicity. Yet in Britain, his victory at Plassey would make him a national hero.

As the monsoon approached, the conspirators finalized their plans. Clive marched from Calcutta with around three thousand troops, British and sepoy, while Siraj assembled a vastly larger force at Plassey, supported by French artillery officers. Mir Jafar’s contingent, ostensibly loyal to the nawab, took its place on the field but awaited the signal to abstain from battle. The die was cast. The fate of Bengal, and arguably of India, now depended on whether a single general would honor his oath or sell his soul for a crown.15

The alliance between Mir Jafar and the Company was thus a convergence of private ambition and corporate strategy. It reflected the emerging logic of imperial capitalism: conquest without the cost of conquest. Bengal was not seized but acquired, its sovereignty traded like a commodity between elites. As P.J. Marshall notes, the Company’s empire began not with invasion but with invitation.16 That invitation, signed in secret by men who claimed to serve Bengal’s welfare, inaugurated a new order in which foreign merchants became kings and native rulers became clerks of empire.

The Battle of Plassey: Betrayal in Action

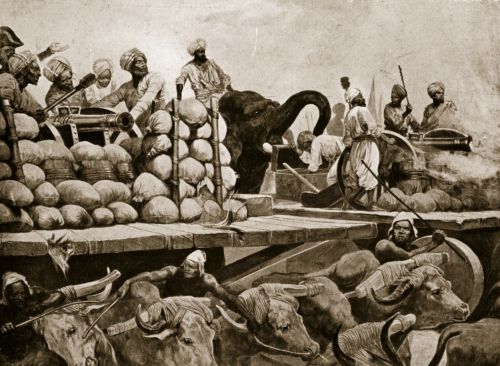

The morning of June 23, 1757, broke humid and gray over the mango groves near the village of Palashi, “Plassey” to the British. On one side stood Siraj-ud-Daulah’s vast army of nearly 50,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and fifty cannons manned by French artillery officers under Monsieur Saint-Frais. Opposing them were barely 3,000 troops under Robert Clive, 900 Europeans and the rest Indian sepoys, supported by a handful of field guns. The disparity in numbers was staggering, but the outcome had already been decided by intrigue. Mir Jafar, commanding a third of the nawab’s army, had secretly pledged neutrality. His men took their positions on the field, resplendent in armor and banners, but their weapons remained cold.17

The battle itself was less a contest of arms than a carefully staged performance of loyalty and betrayal. As the first volleys thundered across the plain, a heavy rain fell, drenching powder and blurring the line between chaos and treachery. Siraj’s front line advanced, believing his full force to be engaged, but the wings held back under Mir Jafar’s command. When the nawab ordered them forward, they did not move. By midday, confusion spread through his ranks; ammunition was ruined, and the French guns fell silent. Clive, seizing the moment, ordered an advance. The disciplined volleys of his infantry, unimpeded by the inaction of Jafar’s troops, shattered what remained of Bengal’s resistance. By evening, the nawab fled the field toward Murshidabad, unaware that his most trusted general had already opened negotiations with the enemy.18

Eyewitnesses to the aftermath described the battle as eerily bloodless for its political consequence. Fewer than a hundred British soldiers were killed, while thousands of Bengalis lay dead or deserted. In Murshidabad, panic spread as word arrived that Clive’s victory was complete. Siraj-ud-Daulah, betrayed and abandoned, attempted to flee toward Patna but was captured and executed by Miran, Mir Jafar’s ambitious son.19 Within days, Clive entered Murshidabad in triumph, escorted by the very men who had once sworn loyalty to the fallen nawab. In the great hall of the Nawab’s palace, amid silks and jewels looted from Bengal’s treasury, Clive placed Mir Jafar on the throne. The ceremony was presented as a restoration of order; in truth, it marked the death of sovereignty.20

The rewards of treachery were immediate. Mir Jafar distributed immense sums to the Company, its officers, and its allies. Clive himself received personal gifts valued at more than £200,000, along with titles and estates. The Company was granted trading privileges, territorial revenues, and military control over Calcutta and its hinterlands. In return, Mir Jafar was left with a hollow crown, an emblem of power without independence. The British, professing to uphold legitimate authority, had instead institutionalized subservience.21 Bengal’s treasury, once the envy of Asia, became a reservoir for European enrichment. The wealth extracted from Plassey financed not only Clive’s fortunes but the expansion of British military power across India.

Plassey was therefore not a battle in the conventional sense; it was a corporate coup executed under the guise of war. Its significance lies not in its scale but in its method: conquest achieved through collusion, diplomacy turned to deception, and profit elevated to principle. The betrayal of Siraj-ud-Daulah by Mir Jafar did not merely change rulers; it inaugurated a new system in which sovereignty itself could be traded, and empire could be built through contract rather than conquest.22 The fields of Plassey, still drenched with the season’s rains, became the first soil of the British Raj.

The Price of Betrayal: From Puppet Nawab to Colonial Province

Mir Jafar’s coronation was celebrated with ceremony and illusion. To the British East India Company, he was the image of legitimacy, a native ruler through whom they could govern Bengal without appearing to do so. To the people of Bengal, he was a figure of betrayal, a general who had traded sovereignty for silver. Once enthroned, he found himself immediately indebted to his new masters. The Company demanded immense sums as payment for its “services” at Plassey: nearly 17 million rupees distributed among officers, shareholders, and the British Crown.23 The first act of Mir Jafar’s reign was therefore not governance but indemnity, a literal sale of his country’s wealth to those who had engineered its defeat.

The economic consequences were catastrophic. To raise the demanded tribute, Mir Jafar stripped the treasury and levied heavy taxes on merchants, artisans, and zamindars. The flow of bullion from Bengal to Britain began in these first months of his rule. P.J. Marshall has documented how the Company’s revenues from Bengal between 1757 and 1765 increased more than tenfold, while domestic production and local investment collapsed.24 The once-flourishing textile industry, dependent on credit and export, suffered as Company monopolies replaced native brokers. Bengal’s prosperity, the foundation of its political autonomy, was systematically dismantled under the guise of reform.

In London, meanwhile, the spoils of Plassey ignited a frenzy of speculation. Shares in the East India Company soared, and Robert Clive was hailed as the savior of British commerce. Parliament, eager to benefit, granted the Company unprecedented privileges in trade and taxation. The model of indirect rule inaugurated by Mir Jafar’s subservience was soon replicated elsewhere. Bengal became the prototype for imperial administration through “dual government”: native rulers retained in name, British officials commanding in fact.25 In this system, the illusion of sovereignty provided the moral cover for exploitation.

Mir Jafar’s position deteriorated rapidly. Unable to satisfy the Company’s constant financial demands and alienated from his own court, he faced mutiny from within. His attempt to seek French assistance provoked British outrage. In 1760, Clive and his successor, Henry Vansittart, deposed him and installed his son-in-law, Mir Qasim, as Nawab. But when Qasim attempted to assert independence by reforming revenue collection and expelling British merchants from Bengal’s markets, he too was defeated and exiled. The cycle of betrayal repeated itself, each new ruler more dependent than the last.26 By 1765, the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II formally granted the diwani, or right to collect revenue, to the East India Company, a symbolic act that made British merchants the legal sovereigns of Bengal.

Mir Jafar lived long enough to witness his own irrelevance. Restored briefly after Mir Qasim’s fall, he remained a puppet, presiding over an empty throne in a land stripped of its wealth. When he died in 1765, the Company had already transitioned from trader to ruler, from supplicant to sovereign. The historian Sushil Chaudhury writes that “the transfer of power from Nawab to Company was accomplished not by conquest but by compliance.”27 Mir Jafar’s compliance, motivated by ambition, unleashed a transformation that would reshape South Asia for more than two centuries. The betrayal of Bengal had become the foundation of empire.

Historical Judgment: Treason, Empire, and the Birth of Corporate Rule

In Indian memory, Mir Jafar’s name became synonymous with treachery. To call someone a “Mir Jafar” was to brand them a traitor to their people, a figure who bartered the nation’s dignity for personal gain. Yet historical judgment must reckon with more than moral condemnation. The betrayal at Plassey was not a singular act of individual corruption; it was the culmination of systemic decay. The disunity of Bengal’s court, the predatory ambitions of the East India Company, and the global rise of corporate capitalism together produced a betrayal that transcended one man. As K.K. Datta observed in his archival study of the Plassey correspondence, Mir Jafar “became both agent and victim of a process larger than himself, a pawn in the first great experiment of economic empire.”28

The colonial transformation that followed revealed the true meaning of this experiment. The Company, originally a private corporation under royal charter, evolved into a political entity with military, judicial, and fiscal authority. Its directors in London governed millions of Indian subjects through the mechanisms of trade and finance. Bengal’s wealth became the engine of Britain’s industrial revolution, funding factories, ships, and the global circulation of capital. Jawaharlal Nehru later described the conquest of Bengal as “the beginning of India’s economic drain, when her wealth became the life-blood of another people.”29 The betrayal thus assumed a structural dimension: the subordination of an entire civilization to the logic of profit.

Historiography has continued to grapple with Mir Jafar’s legacy. Nationalist writers of the twentieth century condemned him as the archetype of collaboration, while revisionist scholars have emphasized the inevitability of Bengal’s fall within the broader collapse of Mughal power.30 Yet neither interpretation absolves him of culpability. His complicity enabled the transformation of the East India Company from a trading concern into a sovereign power, marking the birth of corporate rule in modern history. Ranajit Guha has argued that the Company’s dominance operated “without hegemony,” a regime sustained not by legitimacy but by coercion and complicity.31 Mir Jafar’s alliance with Clive exemplified this condition: sovereignty maintained in name while authority shifted irrevocably to foreign hands.

The story of Mir Jafar endures not only as a chapter of Indian history but as a warning about the entanglement of power and commerce. His betrayal illuminates how empires are not merely imposed from without but constructed from within, through the ambitions of those willing to trade freedom for favor. In 1757, a general’s silence on a rain-soaked battlefield began a new political order, one that replaced monarchs with merchants and citizens with shareholders. The echoes of that moment still resound wherever economic power masquerades as moral right. The empire that began at Plassey was not conquered by soldiers alone; it was authored by the alliance of greed and governance.

Appendix

Footnotes

- P.J. Marshall, Bengal: The British Bridgehead (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 1–4.

- Sushil Chaudhury, From Prosperity to Decline: Eighteenth-Century Bengal (New Delhi: Manohar, 1995), 23–27.

- The Letters of Robert Clive, British Library, Add. MSS 29135–29145.

- P.J. Marshall, The Making and Unmaking of Empires: Britain, India, and America. c.1750-1783 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 115–118.

- William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), 35–38.

- P.J. Marshall, East Indian Fortunes: The British in Bengal in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976), 11–15.

- R.C. Majumdar, The History of Bengal, Vol. 2 (Dacca: University of Dacca, 1943), 314–318.

- Proceedings of the East India Company Court of Directors, 1756–1757, British Library, IOR/E/4/876.

- The Letters of Robert Clive, British Library, Add. MSS 29135–29145.

- Chaudhury, From Prosperity to Decline, 42–45.

- The Letters of Robert Clive, British Library, Add. MSS 29135–29145.

- Marshall, Bengal, 29–32.

- Proceedings of the East India Company Court of Directors, 1757, British Library, IOR/E/4/877.

- H. H. Dodwell, Dupleix and Clive: The Beginnings of Empire (London: Methuen, 1920), 115–119.

- S. B. Chaudhuri, The Transition to Empire: Essays on the Development of British India, 1740–1857 (Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 1975), 67–72.

- Marshall, East Indian Fortunes, 18.

- The Dispatches, Minutes, and Letters of Major-General Robert Clive (London: Murray, 1907), 55–59.

- Proceedings of the East India Company Court of Directors, 1757, British Library, IOR/E/4/877.

- Majumdar, The History of Bengal, 321–324.

- Marshall, Bengal, 46–49.

- Chaudhury, From Prosperity to Decline, 57–60.

- Dalrymple, The Anarchy, 41–45.

- Proceedings of the East India Company Court of Directors, 1757–1758, British Library, IOR/E/4/878.

- Marshall, The Bengal Nawabs and the East India Company, 121–125.

- Ranajit Guha, Dominance without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 15–18.

- Majumdar, The History of Bengal, 338–342.

- Chaudhury, From Prosperity to Decline, 71–73.

- K.K. Datta, Mir Jafar and the Battle of Plassey (Patna: Patna University Press, 1964), 52–55.

- Jawaharlal Nehru, The Discovery of India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1946), 298–301.

- Majumdar, The History of Bengal, 345–348.

- Guha, Dominance without Hegemony, 22–26.

Bibliography

- The Dispatches, Minutes, and Letters of Major-General Robert Clive. London: John Murray, 1907.

- The Letters of Robert Clive. British Library, Additional Manuscripts 29135–29145.

- Proceedings of the East India Company Court of Directors. 1756–1758. British Library, India Office Records, IOR/E/4/876–878.

- Chaudhuri, S. B. The Transition to Empire: Essays on the Development of British India, 1740–1857. Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 1975.

- Chaudhury, Sushil. From Prosperity to Decline: Eighteenth-Century Bengal. New Delhi: Manohar, 1995.

- Dalrymple, William. The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire. London: Bloomsbury, 2019.

- Datta, K. K. Mir Jafar and the Battle of Plassey. Patna: Patna University Press, 1964.

- Dodwell, H. H. Dupleix and Clive: The Beginnings of Empire. London: Methuen, 1920.

- Guha, Ranajit. Dominance without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Majumdar, R. C. The History of Bengal, Vol. 2. Dacca: University of Dacca, 1943.

- Marshall, P. J. Bengal: The British Bridgehead. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- ———. East Indian Fortunes: The British in Bengal in the Eighteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976.

- ———. The Making and Unmaking of Empires: Britain, India, and America. c.1750-1783. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Nehru, Jawaharlal. The Discovery of India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1946.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.