Locusta’s legacy lies not in the sensational details of her craft but in what her life reveals about the structures of Roman political culture.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The career of Locusta occupies a singular place in the political history of the early Roman Empire. She appears in the surviving sources not as a marginal criminal but as a specialist whose knowledge became entangled with the most consequential acts of imperial succession. Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio each record her involvement in the poisoning of the emperor Claudius and in the subsequent death of Britannicus. Their accounts reveal a court culture in which clandestine expertise could be appropriated by those who sought to reshape the imperial order through violent means. Locusta’s presence at these turning points was not a matter of accident but the result of conditions that allowed technical knowledge of poison to become a tool of statecraft.1

Her elevation under Nero further illuminates the mechanisms of power that defined the final years of the Julio Claudian dynasty. After granting her a formal pardon, Nero employed her talents to eliminate Britannicus and then placed her within his household as an instrument of controlled violence. Tacitus describes how the emperor supervised her work and demanded effective results. Suetonius adds that Nero ordered the training of additional poisoners under her instruction. These accounts point to an emerging administrative logic in which assassination was neither impulsive nor irregular but part of a deliberate political strategy.2 The imperial household thus became a setting where the boundary between crime and governance dissolved, leaving Locusta positioned as both beneficiary and servant of a regime that relied on fear to maintain authority.

Locusta’s death under Galba marked an abrupt reversal and signaled a repudiation of Neronian practices. Although the sources offer little detail about the circumstances, their emphasis on her execution situates it within the broader effort to restore legitimacy in the wake of Nero’s suicide.3 The symbolic value of eliminating a figure so closely tied to the secret violence of the previous reign was clear. As the empire shifted into the chaos of the Year of the Four Emperors, the memory of Locusta served as a reminder of how the structures of imperial rule had incorporated techniques of coercion and eradication. Her story offers a window into the political imagination of Rome, where the possession of technical knowledge could be as decisive as the command of legions, and where the boundaries of power were policed not only through armies and law but through the controlled application of invisible harm.

Locusta before Nero: Crime, Reputation, and the Culture of Poison

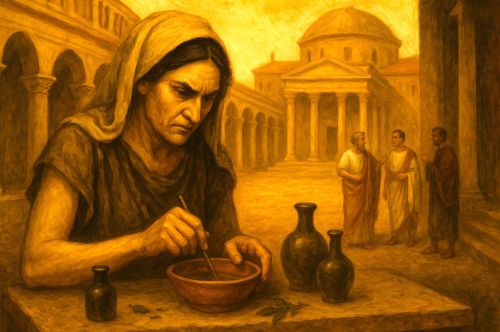

Locusta’s appearance in the historical record begins not with imperial service but with criminal prosecution. Tacitus identifies her as a woman condemned for the practice of veneficium, a category of crime that encompassed poisoning, the manufacture of toxic substances, and related forms of illicit knowledge.4 Her presence in state custody suggests that her abilities were widely known before Agrippina sought her out, and it indicates that she belonged to a class of specialists whom Roman authorities viewed with both fear and utility. The legal context is important. Veneficium stood at the intersection of superstition, social deviance, and violent crime, making it a charge that carried both juridical and moral weight within Roman cultural imagination. The fact that Locusta survived long enough to be retrieved from confinement signals that her skills were considered both dangerous and potentially valuable to those capable of exploiting them.

Roman anxiety surrounding poison shaped the environment in which Locusta operated. Poison was perceived not simply as a criminal act but as an expression of hidden aggression that undermined established hierarchies. Scholars have noted that Roman literature often associates veneficium with women, clandestine knowledge, and social subversion.5 This cultural association influenced how accused poisoners were portrayed and prosecuted. It also helps explain why Locusta’s notoriety was preserved in the sources. She embodied a set of fears about hidden influence and the collapse of public trust, fears that resonated strongly in a society where political stability was fragile and succession often depended on the removal of rivals. Her reputation therefore existed at the convergence of legal suppression and public fascination.

The conditions that brought Locusta to imperial attention reflect broader structural tensions in Roman governance. Claudius’s court and later Nero’s inherited networks of informants, freedmen, and specialists who moved between legality and crime. Policing such figures was sporadic, as Christopher Fuhrmann has shown, and their knowledge made them simultaneously threatening and indispensable.6 Locusta’s early imprisonment provides a glimpse into this fluid world, revealing how the state attempted to control volatile forms of expertise while aristocratic households sought them out for political advantage. Her transition from prisoner to operative under Agrippina and Nero thus becomes more intelligible within the broader framework of a society where specialized skills were both criminalized and exploited, depending on the needs of those in power.

Claudius, Agrippina, and the Politics of Elimination

The transition from Claudius to Nero marked one of the most contested successions of the Julio Claudian period. Ancient historians portray Agrippina as determined to secure Nero’s future, and Locusta’s appearance within this narrative coincides with that political agenda. Tacitus describes Locusta being removed from imprisonment and placed at Agrippina’s disposal as part of an effort to orchestrate Claudius’s death.7 Suetonius and Cassius Dio also report that poison played a role in the emperor’s final illness, reflecting the suspicion that surrounded the circumstances of his demise.8 These accounts illustrate how the mechanisms of succession could involve clandestine actors whose skills were deployed at the command of those closest to the imperial center.

Agrippina’s reliance on poison was connected to her broader strategy of consolidating authority. Her influence over Claudius had already secured Nero’s adoption and positioning as heir, but adoption alone did not guarantee a smooth transition. Tacitus highlights the political necessity of eliminating rival claimants and solidifying Nero’s legitimacy.9 Within this context, the decision to utilize a poisoner was not merely a reflection of personal malice but part of an ongoing contest for survival within the imperial household. Locusta’s role becomes intelligible as a technical component within an intricate and often brutal system of succession management.

The ancient sources differ in their explanations of how the poison was administered. Tacitus reports that the initial dose given to Claudius failed to produce the desired effect, prompting Agrippina to intervene directly with a stronger preparation.10 Suetonius presents a different version that emphasizes deceit within the imperial dining environment.11 These variations do not undermine the central historical thread, which is the prominence of poisoning in the narrative of Claudius’s death. The discrepancies highlight the challenges historians face when interpreting imperial court politics, where secrecy produced multiple competing traditions.

Locusta’s participation in these events demonstrates her emerging significance within the court. Tacitus notes that Agrippina relied on her for the preparation of the poison intended for Claudius, a detail that situates Locusta within the inner sphere of imperial decision making.12 Her movement from incarceration to privileged access underscores the permeability between crime and governance in the early empire. When the needs of those in power aligned with her expertise, Locusta’s status transformed rapidly, revealing how specialized knowledge could override legal boundaries.

Her role in the transition to Nero also illuminates the vulnerability of imperial authority. Poisoning was not simply a matter of removing an emperor. It was a technique that required absolute trust between the orchestrator and the specialist. Agrippina’s decision to employ Locusta indicates confidence in her abilities and discretion, as well as recognition that assassinations conducted through poison could produce political outcomes that were less disruptive than open violence. Scholars have noted that such strategies allowed imperial actors to maintain the appearance of order even while engaging in lethal maneuvers behind the scenes.13 The imperial household thus became a space where technical expertise shaped the trajectory of Roman governance.

Once Claudius was dead, Locusta’s work facilitated the accession of Nero, whose youth made him reliant on the structures Agrippina had constructed. The events that followed demonstrate how tightly woven the fates of rulers and their operatives could become. Locusta’s involvement in the death of Claudius placed her within Nero’s sphere of influence from the first moments of his reign. That proximity would soon be formalized as Nero drew her more deeply into his own systems of control, setting the stage for her heightened role in the assassination of Britannicus and in the development of a state sponsored apparatus of poisoning.14 In this sequence of events, Locusta emerges not only as a figure of criminal notoriety but as a technician whose skills intersected decisively with the politics of succession.

Nero’s Patronage: Locusta as Imperial Technician of Death

Locusta’s position changed dramatically once Nero assumed full authority. Tacitus records that Nero pardoned her early in his reign and rewarded her with land and privileges, transforming a condemned poisoner into a valued member of his household.15 This gesture was not an act of clemency but a deliberate incorporation of her expertise into the machinery of the imperial court. The pardon signals that Nero intended to rely on her skills and that he recognized the strategic value of retaining a specialist capable of delivering precise and unobtrusive forms of violence.

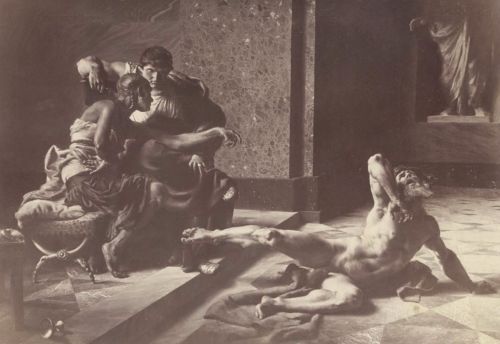

Her most consequential task under Nero was the poisoning of Britannicus, an event described in detail by Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio. Tacitus explains that Nero summoned Locusta to prepare a poison fast acting enough to eliminate Britannicus during a banquet.16 Her initial preparations were judged insufficiently potent, prompting Nero to supervise the refinement of the mixture.17 Suetonius likewise portrays Nero as personally involved in ensuring the poison’s effectiveness.18 These accounts indicate that Locusta’s actions were conducted under imperial direction and that her role was instrumental in removing a potential rival whose lineage posed a threat to Nero’s legitimacy.

The successful killing of Britannicus elevated Locusta’s status further. Suetonius reports that Nero provided her with students to train in the art of poisoning.19 This detail suggests that Locusta’s role extended beyond singular assignments and that she became a central figure in developing a cadre of specialists intended to serve the emperor’s interests. Her activities reveal an institutionalization of clandestine violence within Nero’s domestic administration. What had previously been ad hoc became part of a structured system in which expertise was transmitted and preserved.

Locusta’s integration into Nero’s court also demonstrates a broader pattern of how specialized knowledge functioned within the imperial household. Tacitus notes that Nero relied increasingly on individuals whose skills operated outside traditional legal structures.20 Although the historian is generally critical of Nero, his observations highlight how these figures supported an environment in which the emperor could act with fewer constraints. Locusta’s technical abilities gave Nero a method of neutralizing threats without provoking the public spectacle associated with executions. Her presence allowed the emperor to maintain an image of stability even while employing lethal strategies behind closed doors.

The partnership between Nero and Locusta reveals the mutual dependence that could develop between rulers and their operatives. Nero’s authority granted Locusta protection, resources, and influence. In return, her knowledge provided a form of power that conventional instruments of governance could not supply. Scholars have observed that this period marked a shift in the ways Roman emperors managed internal threats, emphasizing secretive control over open displays of coercion.21 Locusta’s career exemplifies this development. Her services became a component of Nero’s broader efforts to fortify his rule through calibrated forms of elimination that shaped the politics of the later Julio Claudian dynasty.

Poison as Statecraft: Surveillance, Fear, and the Julio-Claudian Court

The use of poison in the Julio Claudian court was not an aberration but part of a structured environment in which rulers relied on secrecy to manage threats. Tacitus emphasizes that suspicion and fear shaped elite behavior during Nero’s reign, and the deployment of poison contributed to this atmosphere.22 Although the historian writes with a moralizing tone, his narrative indicates that the uncertainty surrounding deaths at court created a climate in which no aristocrat could feel secure. Locusta’s position within this system meant that her work had political impact far beyond the individuals she targeted.

The assassination of Britannicus reinforced the perception that the emperor had embraced clandestine violence as a governing tool. Tacitus describes how the young prince’s sudden death was met with alarm among those who understood its implications.23 The swift and silent removal of a potential heir signaled that Nero was willing to bypass legal or ceremonial methods in securing his authority. Locusta’s role in crafting the poison made her a recognizable symbol of this shift. The knowledge that the emperor had someone capable of effecting such deaths discouraged open resistance and encouraged self-protective alliances within the aristocracy.

Suetonius offers a portrait of Nero’s reliance on secretive means to eliminate perceived enemies, providing a context in which Locusta’s expertise operated.24 The biographer presents a court where surveillance, fear, and covert punishment shaped interactions between the emperor and the elite. Although Suetonius often includes anecdotal material, his emphasis on the hidden nature of Nero’s violence aligns with the historical reality that poison functioned as a discreet method of political control. Locusta’s ability to produce targeted and efficient toxins contributed to the emperor’s capacity to enforce obedience without resorting to public executions.

The moral and cultural anxieties surrounding poison magnified Locusta’s influence. Roman literature often describes veneficium as a hidden assault that erodes trust within households and communities.25 This cultural perception meant that the identity of a known poisoner carried exceptional symbolic weight. Her presence at court reminded observers that the emperor could discipline or eliminate adversaries through means that left few traces. As a result, Locusta’s technical knowledge became intertwined with the psychological strategies that sustained Nero’s authority.

The integration of poisoning into the logic of imperial power reveals the extent to which specialized skills could reshape the political landscape. Scholars have emphasized that clandestine methods of coercion were not secondary features of the Julio Claudian administration but essential components of its functioning.26 Locusta’s work demonstrates how the imperial household incorporated individuals whose criminal backgrounds were repurposed to support centralized control. Her career illuminates a broader transition in Roman governance, one in which the management of threats increasingly relied on discrete and technical forms of violence that operated beneath the surface of public life.

The Fall: Galba, Purges, and the End of Locusta

Locusta’s execution under Galba occurred within a broader effort to dismantle the structures of violence that had sustained Nero’s rule. Suetonius identifies her death as part of a series of measures undertaken immediately after Galba entered Rome.27 These actions formed a symbolic repudiation of practices associated with the previous reign. Locusta’s prominence as an imperial poisoner made her one of the most visible embodiments of Neronian excess, and her elimination served as a public declaration that the new administration sought to distance itself from secretive forms of coercion. The decision reflects the political need to signal a decisive break from the mechanisms of power that had supported Nero’s authority.

Tacitus, writing about the chaotic transition from Nero to Galba in the early pages of the Histories, stresses the importance of restoring legitimacy after a period marked by spectacle, informants, and fear.28 Although he does not dwell on Locusta herself at this stage, his analysis clarifies the context in which Galba acted. The new emperor inherited a state in which hidden networks of influence had replaced traditional modes of governance. In this environment, purging figures tied to the abuses of the previous regime offered a tangible means of reasserting order. Locusta’s execution must therefore be understood within the political logic of reestablishing trust in imperial leadership.

Cassius Dio’s narrative likewise connects Galba’s early purges to the need for consolidating authority during a highly unstable moment. Dio portrays Galba as attempting to correct the moral disarray associated with Nero.29 Locusta’s fate fits this framework. Her death was not solely punitive but corrective, designed to restore confidence in an imperial system that had relied on clandestine violence. Dio’s emphasis on moral reform reflects the perception among ancient historians that the removal of individuals like Locusta was essential for public reassurance.

Modern scholarship reinforces this interpretation. Studies of the Year of the Four Emperors highlight how each leader sought to legitimize his rule amid rapid turnover and contested succession.30 Eliminating those who symbolized the extremes of Nero’s administration enabled Galba to present himself as a restorer of traditional norms. Locusta’s reputation, wholly shaped by the clandestine operations of the Julio Claudian household, made her an ideal target for such political messaging. Her execution thus operated both as justice for past crimes and as a tool for framing Galba’s reign as a corrective moment.

Locusta’s death also reveals the fragility of the positions held by imperial specialists. Her career demonstrates how individuals who served the needs of one emperor could quickly become liabilities to the next. Once the structures that protected her dissolved, she had little recourse. Her fate underscores how the imperial household created and consumed technical expertise, elevating figures like Locusta when their skills were useful and discarding them when their presence threatened the legitimacy of new rulers. In this sense, her execution marks not only the end of her own career but also the transformation of the political order that had sustained her.

Conclusion: Locusta’s Legacy and the Politics of Violence in Imperial Rome

Locusta’s trajectory from imprisoned poisoner to imperial instrument and finally to executed symbol of tyranny reveals the unstable balance between expertise and power in the early Roman Empire. Her actions did not occur in isolation. They belonged to a political culture in which rulers navigated succession, rivalry, and legitimacy through strategies that combined spectacle with secrecy. Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio all preserve accounts that position Locusta within this system, not as an outlier but as a participant shaped by the needs and fears of the imperial household.31 Her life allows historians to trace the contours of a political environment where hidden forms of coercion became essential tools of governance.

Her service under Nero demonstrates how technical knowledge could become a form of political capital. The emperor’s reliance on her skills to eliminate Britannicus and to train others reveals an administrative integration of clandestine violence that went beyond occasional intrigue. The Julio Claudian court increasingly depended on individuals whose abilities operated outside public norms, and Locusta became a figure through whom that dependence took material form. Scholars have noted that Nero’s reign illustrates a broader shift toward systems of control that emphasized secrecy and targeted elimination.32 Locusta’s activities illuminate how those systems functioned from within.

The reaction to her presence at court was shaped by cultural anxieties about poison. Veneficium carried moral and symbolic weight in Roman society, and the idea of a state sponsored poisoner heightened existing concerns about declining public virtue and the erosion of traditional authority. Locusta’s notoriety in ancient literature reflects not only the extraordinary nature of her assignments but also the fears they provoked.33 Her name became shorthand for the hidden dangers of imperial rule, a reminder that the emperor held methods of coercion that defied public scrutiny.

Galba’s decision to execute Locusta underscores how visible she had become in the political landscape. Her death marked a deliberate attempt to reframe the nature of imperial authority after Nero’s fall. Removing a figure so closely associated with secret violence communicated a desire to restore conventional forms of governance.34 Yet the need for such an act also demonstrates how deeply Nero’s reliance on clandestine specialists had shaped perceptions of imperial power. Locusta’s execution was therefore both a political gesture and a recognition of the anxiety her career had generated.

Locusta’s legacy lies not in the sensational details of her craft but in what her life reveals about the structures of Roman political culture. She represents a convergence of gender, crime, and technical expertise that complicates simplistic narratives of imperial decadence. The Julio Claudian dynasty used her abilities to manage internal threats and secure succession. Later rulers sought to erase the memory of that dependence. Locusta’s story thus offers a lens through which to understand how violence functioned within the empire, not only through armies and law but through individuals whose skills connected the visible and invisible realms of power.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Tacitus, Annals 12.66–67; Suetonius, Nero 33; Cassius Dio, Roman History 61.7.

- Tacitus, Annals 13.14–17; Suetonius, Nero 33.

- Suetonius, Galba 11; Cassius Dio, Roman History 63.3.

- Tacitus, Annals 12.66.

- Francois P. Retief and Louise Cilliers, “Poisons, Poisoning, and Poisoners in Rome,” Medicine Antiqua.

- Christopher Fuhrmann, Policing the Roman Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Tacitus, Annals 12.66.

- Suetonius, Claudius 44; Cassius Dio, Roman History 61.34.

- Tacitus, Annals 12.41.

- Tacitus, Annals 12.67.

- Suetonius, Claudius 44.

- Tacitus, Annals 12.66–67.

- Anthony A. Barrett, Agrippina: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Early Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

- Tacitus, Annals 13.14–17.

- Tacitus, Annals 13.15.

- Tacitus, Annals 13.16.

- Tacitus, Annals 13.16–17.

- Suetonius, Nero 33.

- Suetonius, Nero 33.

- Tacitus, Annals 13.14.

- Miriam Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty (London: Routledge, 1984).

- Tacitus, Annals 13.16.

- Tacitus, Annals 13.16–17.

- Suetonius, Nero 33.

- Catharine Edwards, Death in Ancient Rome (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

- Shadi Bartsch, Actors in the Audience: Theatricality and Doublespeak from Nero to Hadrian (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994).

- Suetonius, Galba 11.

- Tacitus, Histories 1.4–5.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 63.3.

- Martin Goodman, The Roman World 44 BC to AD 180 (London: Routledge, 1997).

- Tacitus, Annals 12.66–13.17; Suetonius, Nero 33; Cassius Dio, Roman History 61.7.

- Griffin, Nero.

- Edwards, Death in Ancient Rome.

- Suetonius, Galba 11.

Bibliography

- Barrett, Anthony A. Agrippina: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Early Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

- Bartsch, Shadi. Actors in the Audience: Theatricality and Doublespeak from Nero to Hadrian. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History.

- Edwards, Catharine. Death in Ancient Rome. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Fuhrmann, Christopher. Policing the Roman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Goodman, Martin. The Roman World 44 BC to AD 180. London: Routledge, 1997.

- Griffin, Miriam. Nero: The End of a Dynasty. London: Routledge, 1984.

- Retief, Francois P. and Louise Cilliers. “Poisons, Poisoning, and Poisoners in Rome.” Medicine Antiqua.

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars.

- Tacitus. Annals.

- Tacitus. Histories.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.13.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.