The history of Nazi eugenics demonstrates how pseudoscientific ideas can be transformed into instruments of unprecedented violence when combined with authoritarian power.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: From Eugenics to Extermination

The rise of Adolf Hitler brought eugenics to its most violent and catastrophic expression. What had begun internationally as a movement claiming to promote public health and national improvement became, in Nazi Germany, a state doctrine that redefined human worth in biological terms and sanctioned the destruction of entire populations. Hitler interpreted heredity as the governing force of history, arguing that the survival of the German nation depended upon protecting what he described as the Nordic or Aryan race from internal decay and external threat.1 These ideas did not emerge in a vacuum. They drew upon earlier medical, anthropological, and eugenic discourses circulating across Europe and the United States, but the Nazi regime radicalized those frameworks by institutionalizing racial hierarchy, coercive reproduction control, and ultimately systematic murder.

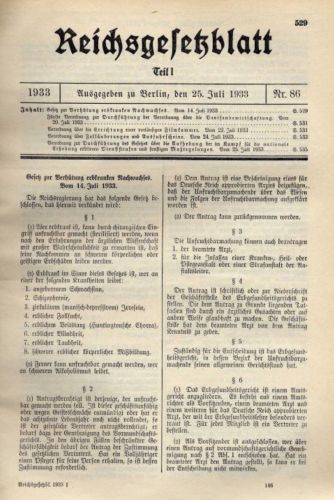

From the moment the Nazis came to power, the regime sought to codify its racial worldview in law and public policy. In July 1933, the government enacted the Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring, which authorized compulsory sterilization for a wide range of conditions that officials claimed were hereditary, including intellectual disability, schizophrenia, and epilepsy.2 Hereditary Health Courts staffed by physicians reviewed cases and issued thousands of sterilization orders each month. By the outbreak of the Second World War, roughly 400,000 people had been sterilized without their consent.3 This legislation provided the first bureaucratic mechanism for identifying, categorizing, and intervening in the lives of individuals whom the regime regarded as biological threats to the national community.

The Nazi worldview escalated from sterilization to killing when the state adopted policies targeting the disabled as burdens to the German Volk. Medical and legal debates in Germany before 1933 had already introduced the notion of “life unworthy of life,” which argued that certain individuals lacked the physical or mental capacity to participate in society and therefore drained national resources.4 Under Hitler, these ideas became the basis for Aktion T4, a centrally organized program that murdered institutionalized patients through lethal injection or carbon monoxide gas.5 Physicians, nurses, and administrators played a direct role in these killings, developing methods and expertise that were later transferred to extermination camps in occupied Poland.

By the time the Holocaust began, the Nazi regime had already built the conceptual, legal, and technical foundations for genocide. Racial hygiene provided the ideological justification for identifying Jews, Roma, and other targeted groups as biological enemies. Forced sterilization and the T4 program created professional networks capable of mass killing. Wartime policies gave the regime the conditions under which it could implement extermination as the ultimate solution to what it defined as racial pollution.6 The Final Solution did not represent a break from Nazi eugenics but its culmination, demonstrating how pseudoscientific theories of heredity can become instruments of unprecedented violence when harnessed to totalitarian power.

The Intellectual Roots of Nazi Eugenics

Nazi racial hygiene drew upon several intellectual traditions that predated the Third Reich but transformed them into a singular and devastating ideology. Central among these was the völkisch movement, a constellation of nationalist, romantic, and racial theories that emerged in late nineteenth century Germany. These thinkers imagined the German Volk as a biologically unified community whose survival required protection from foreign and internal enemies. Their writings fused mythic notions of ancient Germanic purity with anxieties about modernity, industrialization, and social fragmentation.7 Although these ideas lacked scientific grounding, they contributed to a cultural environment in which racial identity appeared natural, primordial, and determinative.

Social Darwinism provided a second major foundation. While Charles Darwin’s work did not advocate racial hierarchy or human-directed selection, European interpreters soon applied evolutionary theory to social and political life. Herbert Spencer and other writers claimed that human groups were locked in a struggle for survival and that state intervention to protect the weak violated natural law.8 German racial theorists absorbed these notions, arguing that the survival of the nation depended upon eliminating degeneracy and promoting the reproduction of those deemed racially valuable. By the early twentieth century, such theories allowed political actors to frame inequality and exclusion as biologically necessary rather than morally or socially constructed.

International eugenics movements also played a decisive role. In the early 1900s, the United States had already enacted sterilization laws targeting the “feebleminded,” mentally ill, and those considered socially deviant. These policies were justified through claims about hereditary criminality and social burden.9 German racial hygienists studied these laws closely, attending international conferences and publishing in transnational journals that linked American, British, Scandinavian, and German eugenicists. Historians have demonstrated that German officials explicitly modeled early legislation on U.S. state statutes, particularly those of California, which had sterilized thousands of individuals well before Hitler seized power.10 The perceived success of American policies convinced many German physicians and lawmakers that compulsory sterilization was both scientifically grounded and socially beneficial.

Hitler synthesized these disparate traditions into a coherent worldview centered on racial struggle. In Mein Kampf, he described history as a contest among races whose biological qualities determined their cultural achievements and political fate.11 This interpretation of human history justified the exclusion, sterilization, and eventual annihilation of those whom he deemed racial enemies. By combining völkisch nationalism, social Darwinism, and international eugenic theory, Nazi ideology constructed heredity as the master principle of social organization and policy. What distinguished the Nazi program was not its intellectual roots, but the radical extent to which the regime sought to operationalize them through law, medicine, and ultimately genocide.12

Racial Superiority and the Myth of the “Aryan”

Nazi racial ideology placed the so-called Aryan or Nordic race at the apex of human hierarchy. German racial theorists of the early twentieth century depicted this group as the bearer of cultural creativity, political strength, and moral virtue. These ideas drew on earlier anthropological theories that attempted to classify Europeans into distinct racial types using skull measurements, facial indices, and other pseudoscientific markers. Although these typologies lacked empirical validity, they were presented as authoritative in German academic and medical institutions.13 Through this intellectual scaffolding, the Nazi regime framed the Aryan race not as a cultural construct but as a biological reality that required state protection.

The institutionalization of this myth accelerated after 1933. German universities, racial hygiene offices, and the SS Race and Settlement Main Office produced studies claiming to measure Nordic characteristics in the population. These research programs used photography, anthropometry, genealogical charts, and biometric testing as tools for defining racial worth. Heinrich Himmler’s SS adopted these methods to evaluate applicants, insisting that only those with “Nordic” features and lineage could join the elite order.14 Such practices created an administrative culture in which racial value was assessed through techniques that falsely presented themselves as scientific, lending legitimacy to policies of exclusion and persecution.

Nazi racial science also constructed Aryan superiority by contrast. Jews, Roma, and other targeted groups were characterized as biologically alien, corrupting, or parasitic, categories rooted in long-standing European prejudices but reformulated in hereditary terms. Medical journals, school textbooks, and propaganda materials depicted these groups as physical and moral opposites of the Nordic ideal.15 By casting biological identity as destiny, the regime reinforced the notion that coexistence was impossible and that the health of the nation required segregation, sterilization, or removal of those labeled as racial enemies.

Hitler’s own writings helped enshrine these beliefs at the highest level of policy. In Mein Kampf, he asserted that the decline of past civilizations resulted from racial mixing and the loss of Aryan purity.16 These arguments provided ideological justification for the regime’s later measures restricting marriage, controlling reproduction, and excluding Jews from civic life. Nazi leaders invoked racial science to present their actions as measures of national defense rather than as political or religious persecution. This reframing turned prejudice into policy and presented genocide as a biological necessity.

By elevating the myth of Aryan superiority to state doctrine, the Nazi regime created an ideological system that shaped every aspect of German public life. Laws, educational curricula, medical practice, and cultural institutions all reinforced the message that the German nation’s survival depended upon protecting the Nordic race.17 This conviction not only justified forced sterilization and social segregation but also prepared the conceptual ground for the Final Solution. The imagined purity of the Aryan race thus became both the foundation and the justification for unprecedented crimes.

“Life Unworthy of Life”: Disability, Degeneracy, and Eugenic Targeting

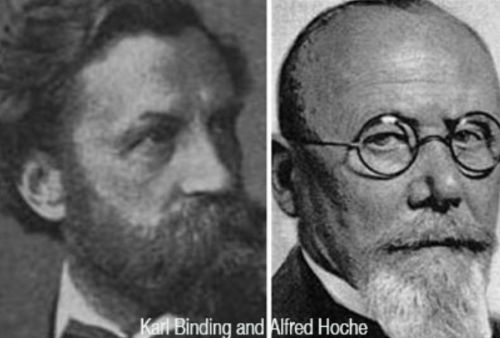

The category of “life unworthy of life” emerged from early twentieth century German debates at the intersection of medicine, law, and social policy. Although the phrase was popularized by jurist Karl Binding and psychiatrist Alfred Hoche in their 1920 tract arguing for the permissibility of killing individuals deemed irredeemably disabled, its underlying assumptions had deeper roots in European thinking about degeneration and heredity. Binding and Hoche claimed that some people lacked what they considered the minimal capacity for meaningful existence and that their continued survival placed unacceptable burdens on families and the state.18 Their arguments introduced a vocabulary that reframed disability as a threat to the national body rather than a condition requiring care.

The Nazi regime adopted and expanded this logic after 1933. Physicians and public health officials categorized a wide range of physical, intellectual, and psychiatric disabilities as hereditary defects that endangered the German population. Medical propaganda depicted institutionalized patients as drains on national resources, often presenting stylized calculations of the costs of care to justify sterilization or elimination.19 These portrayals framed disabled individuals as biological liabilities whose existence undermined the strength of the Volk. In this way, Nazi racial hygiene transformed earlier debates into state doctrine, integrating medical authority with ideological claims about national vitality.

Institutional practices reinforced these ideological shifts. Doctors were required to report patients diagnosed with conditions identified as hereditary under the 1933 sterilization law, a process that expanded the state’s surveillance of the disabled and created mechanisms for identifying entire categories of people for sterilization or confinement.20 The involvement of medical professionals gave the regime an aura of scientific legitimacy, allowing it to present coercive measures as evidence-based responses rather than acts of persecution. The medicalization of disability thus became central to the Nazi project, turning physicians into agents of the state’s racial goals.

These policies also drew upon economic rationales. Nazi officials argued that disabled individuals consumed resources that could be redirected toward the war effort or toward the support of “valuable” families.21 Although such claims were framed as fiscal necessity, they relied on pseudoscientific assumptions that equated disability with hereditary inferiority and social burden. Economic arguments therefore masked ideological commitments, presenting the elimination of the disabled as a pragmatic solution to national challenges rather than as a fundamental departure from medical ethics.

As the regime radicalized, the logic of “life unworthy of life” provided the foundation for Aktion T4, the centralized killing program that targeted institutionalized patients.22 The transition from sterilization to murder marked the full realization of the earlier medical-legal argument that some lives lacked value. The program’s techniques, personnel, and administrative structures became essential components of the Holocaust, demonstrating how the stigmatization of disability created a template for broader categories of elimination. The ideology of hereditary degeneracy thus became a powerful instrument of state-sponsored violence, shaping both the conceptual and practical foundations of genocide.

Foreign Models: U.S. Eugenics and Nazi Imitation

The international eugenics movement strongly shaped the early racial hygiene policies of Nazi Germany. In the decades before Hitler’s rise to power, American eugenicists had already developed extensive programs of compulsory sterilization, immigration restriction, and hereditary classification. These policies, grounded in pseudoscientific claims about racial fitness and genetic burden, created a global reference point for reformers who believed that social problems could be addressed by regulating reproduction.23 German racial hygienists studied these developments closely, incorporating foreign methods into their own policy proposals and presenting them as evidence that hereditary intervention was both practical and socially acceptable.

Hitler expressed admiration for American eugenic policies before assuming power. In Mein Kampf, he praised U.S. immigration laws for protecting what he saw as racial quality and restricting entry based on national origin.24 These views aligned with the broader enthusiasm among German racial hygienists for American sterilization laws, particularly those implemented in California, which by the early 1930s had sterilized more individuals than any other U.S. state. German researchers translated and circulated American publications, and German physicians attended international conferences where U.S. delegates described the organization and rationale of their programs.25 This transnational exchange offered German policymakers an institutional model they would later adapt for their own purposes.

Professional networks strengthened these connections. Prominent American eugenicists such as Harry H. Laughlin corresponded with German colleagues, provided statistical analyses, and advised on legislative design. Laughlin’s “Model Eugenical Sterilization Law” received wide attention in Germany and influenced discussions about hereditary health legislation in the early 1930s.26 German experts cited American sterilization decisions in legal journals and academic treatises, arguing that the United States had already demonstrated the feasibility of large-scale reproductive control. The perception that eugenics enjoyed democratic legitimacy in America further emboldened German officials seeking to institutionalize similar programs.

The influence of American policies did not diminish once the Nazis gained power. After 1933, the newly established German Hereditary Health Courts continued to monitor developments abroad, and racial hygienists maintained contact with American sterilization advocates. International eugenics journals published favorable reviews of German legislation, while American authors sometimes praised the perceived efficiency of Nazi racial hygiene.27 Although the goals of the two systems differed, American programs emphasized institutionalization and sterilization, while the Nazis pursued radical racial transformation, the early stages of Nazi policy reflected clear borrowings from foreign precedents.

These transnational exchanges reveal that Nazi eugenics did not develop in isolation. While the regime’s later genocidal policies had no parallel in the United States or elsewhere, the conceptual framework for early German legislation drew heavily from American theories of hereditary fitness and social engineering.28 The shared belief that public health required biological intervention created an intellectual environment in which coercive policies appeared both modern and scientifically justified. The Nazis would later exploit this foundation to pursue far more destructive ends, but the influence of foreign models shaped the initial contours of their racial hygiene program.

The 1933 Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring

The passage of the 1933 Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring marked the first major legislative embodiment of Nazi racial hygiene. Enacted only months after Hitler assumed power, it authorized compulsory sterilization for individuals diagnosed with conditions the regime categorized as hereditary, including schizophrenia, “congenital feeblemindedness,” epilepsy, hereditary blindness and deafness, and chronic alcoholism.29 The law framed sterilization as a public health measure that would protect future generations from what Nazi officials described as genetic decay. Its language drew heavily from terminology circulating in international eugenics movements yet placed these concepts within a new authoritarian framework that empowered the state to determine reproductive futures.

Implementation of the law required the creation of Hereditary Health Courts, special tribunals staffed by physicians and judges who reviewed sterilization petitions submitted by medical professionals. These courts operated with extraordinary efficiency. By 1934, thousands of cases were being processed each month, with approval rates exceeding 85 percent.30 The structure of the courts ensured that medical expertise appeared central to decision making, but in practice physicians often acted as instruments of state policy rather than independent evaluators. The medical profession’s enthusiastic cooperation provided the regime with a veneer of scientific legitimacy that obscured the profound ethical violations inherent in compulsory sterilization.

The law also expanded the reach of state surveillance. Physicians, midwives, teachers, and welfare officials were required to report individuals suspected of having hereditary conditions.31 These reporting mechanisms generated vast bureaucratic files that documented family histories, institutional records, and clinical assessments, creating a population-wide system for monitoring hereditary “fitness.” The expansion of surveillance into schools, hospitals, and municipal offices normalized the idea that reproduction was a matter of state concern. It also reinforced the belief that hereditary traits could be reliably identified, categorized, and controlled through administrative measures, even though the scientific basis for such claims was deeply flawed.

By the outbreak of the Second World War, an estimated 400,000 people had been sterilized under the law, establishing a coercive system that paved the way for far more radical measures.32 The infrastructure created in 1933 (health courts, reporting networks, medicalized terminology, and bureaucratic monitoring) formed the foundation that linked early eugenic legislation to the regime’s later killing programs. The compulsory sterilization law demonstrated the Nazi state’s willingness to intervene in the most intimate aspects of life and signaled the beginning of a broader project that would ultimately culminate in the Final Solution.

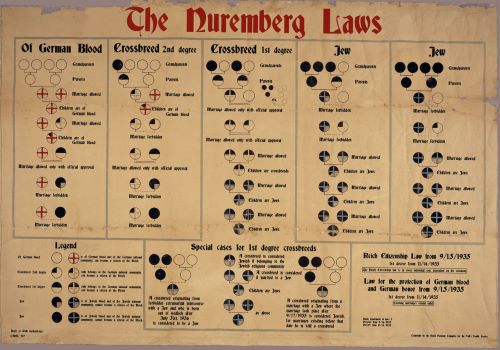

The Nuremberg Laws and the Racialization of Marriage

The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 transformed Nazi racial ideology into a comprehensive legal framework that reshaped citizenship, intimacy, and personal identity. Central among them were the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, which together created a system that defined who could belong to the German nation and who was excluded on racial grounds.33 These measures designated Jews as subjects without full political rights and prohibited marriages or sexual relations between Jews and those classified as “German or related blood.” The laws reflected the regime’s conviction that racial boundaries must be policed at the most intimate levels to ensure the survival of the Aryan race.

The laws introduced a bureaucratic apparatus that required individuals to prove their ancestry through genealogical documentation. Government forms demanded evidence of racial lineage, often tracing family history back three generations.34 Racial classification became an administrative requirement for marriage, employment, and public service, embedding pseudoscientific assumptions into everyday life. Clerks, teachers, clergy, and officials across the Reich became responsible for enforcing these categories, ensuring that racial identity governed access to fundamental civil rights. The regime’s emphasis on ancestry and biological descent turned marriage into a site for policing racial purity.

These policies extended the logic of the earlier sterilization program by preventing reproductive mixing between Jews and so-called Aryans. Nazi propaganda depicted such unions as threats to national survival, claiming that interracial relationships weakened the racial character of the Volk.35 The racialization of marriage thus served both ideological and practical functions: it framed Jewish identity as biologically incompatible with German national life and created legal structures for separating Jews from German society. Although rooted in longstanding European antisemitic traditions, the Nuremberg Laws recast prejudice into a hereditary narrative enforced through legal and medical institutions.

The impact of the laws intensified as war approached. Racial definitions expanded to include categories such as “Mischlinge,” or individuals of mixed Jewish and non-Jewish ancestry, who were subjected to increasing restrictions.36 These classifications facilitated the segregation, dispossession, and eventual deportation of Jews throughout the Reich. By embedding racial ideology within civil law, the Nuremberg Laws laid the groundwork for the Final Solution, demonstrating how bureaucratic measures governing marriage and citizenship could evolve into instruments of genocide.

Aktion T4: From Sterilization to Systematic Murder

Aktion T4 marked the Nazi regime’s transition from policies of reproductive control to deliberate, centralized killing. Launched in 1939 under Hitler’s secret authorization, the program targeted institutionalized psychiatric patients and individuals with severe disabilities, whom officials classified as burdens on the state and threats to the health of the German Volk.37 The initiative emerged directly from the ideological logic of “life unworthy of life,” but it represented a significant shift from sterilization to extermination. Physicians selected patients for death using questionnaires that masked the lethal intent of the program, turning medical assessment into a tool of state violence.

The killing centers established under T4 introduced technologies and procedures that later became central to the Final Solution. Six facilities, including Hartheim, Hadamar, and Grafeneck, were equipped with gas chambers that used carbon monoxide piped from cylinders into sealed rooms designed to resemble showers.38 Victims were transported in buses with blacked-out windows, and staff carried out the murders with bureaucratic precision. After gassing, bodies were cremated, and families received falsified death certificates to conceal the nature of the killings. These methods created an administrative and technical template for mass murder that expanded beyond the boundaries of the euthanasia program.

Medical professionals played a crucial role in legitimizing T4. Physicians oversaw patient selection, supervised gassing procedures, and conducted research on the bodies of victims.39 Their participation helped maintain an internal culture of scientific justification, framing the killings as necessary public health interventions rather than moral atrocities. The integration of medical expertise with state violence demonstrated how professional authority could be manipulated to support ideological goals, eroding ethical norms and enabling systematic brutality. Nurses, clerks, and administrative staff also participated, illustrating how the program relied on broad institutional cooperation.

Public reaction to the killings eventually generated significant resistance. In 1940 and 1941, clergy, family members, and some local officials protested the deaths of institutionalized patients, culminating in outspoken sermons such as those by Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen.40 These protests contributed to Hitler’s decision to halt the visible phase of T4 in August 1941, but the cessation was only superficial. Decentralized killings continued in hospitals and institutions, and the expertise developed during the official phase of T4 persisted in the medical system. The temporary suspension thus did little to diminish the program’s long-term impact.

The most consequential legacy of Aktion T4 was the transfer of personnel, techniques, and organizational models to extermination camps in occupied Poland. After the official end of T4, many of the program’s administrators and technicians were reassigned to Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka, where their experience in deception, gassing procedures, and mass cremation became essential to the construction of Operation Reinhard.41 Aktion T4 was therefore not an isolated campaign but a critical step in the evolution of Nazi genocide, bridging the gap between domestic eugenic violence and the industrialized killing that defined the Holocaust.

The Transfer of Methods: T4 to the Concentration Camps

The machinery of the Holocaust did not arise suddenly in 1941. It evolved directly from the infrastructure, personnel, and techniques developed during Aktion T4. When the official phase of the euthanasia program ended in August 1941, the Nazi leadership redirected its experienced staff to new assignments in occupied Poland. Many of the doctors, administrators, gas technicians, and clerical workers who had participated in T4 formed the core of the killing operations at Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka.42 Their expertise in deception, transport logistics, gassing procedures, and mass cremation made them uniquely suited to implement the next stage of the regime’s racial agenda.

The transfer of personnel reflected a deliberate strategy. Christian Wirth, one of the leading figures of Aktion T4, became the commandant of Belzec and later inspector of Operation Reinhard, overseeing the extermination of Jews in the General Government.43 Wirth brought with him the organizational model of T4: centralized leadership, medical authority, expertly trained killing teams, and methods designed to maximize efficiency while minimizing resistance. His arrival signaled the continuity between the euthanasia program and the broader project of genocide. The staff who followed him carried not only practical skills but also the ideological conditioning that enabled them to view mass murder as a necessary public health measure.

Technologies first developed or perfected during T4 became integral to extermination camp operations. Gas chambers modeled on those used at Grafeneck and Hadamar appeared in the camps of Operation Reinhard, though adapted for larger-scale killing. Carbon monoxide delivered from stationary engines replaced bottled gas, but the underlying principles (victims herded into sealed rooms disguised as showers, rapid killing, and immediate cremation) remained consistent.44 The crematoria at T4 sites had demonstrated the feasibility of processing large numbers of bodies; camp personnel simply extended these techniques to the far greater scale required for the annihilation of European Jewry.

Bureaucratic methods also migrated from T4 into the structure of the extermination apparatus. The systematic use of transport lists, intake forms, coded communications, and falsified death documentation had been refined under the euthanasia program. In the camps, similar systems organized deportations, recorded prisoner selections, and managed the disposal of victims’ property.45 The administrative routines developed during T4 gave genocide a procedural normality that concealed the enormity of the crimes behind familiar institutional practices. This bureaucratization made mass murder appear manageable and orderly, reinforcing the idea that killing was simply another state function.

Deception, a hallmark of the euthanasia program, became a central feature of the camps. T4 operators had learned to maintain secrecy through misleading correspondence, false diagnoses, and carefully orchestrated transport procedures that minimized public scrutiny. Camp personnel expanded these techniques by designing arrival areas that resembled transit stations, creating delousing narratives, and using prisoner labor to ease the movement of victims.46 This continuity in deception highlights the ideological continuity between the programs: both relied on the belief that state-directed killing could be hidden beneath a veneer of administrative normalcy and medical necessity.

The cumulative effect of these transfers was that the Holocaust emerged not merely from radical antisemitism but from an institutional evolution of earlier killing practices. T4 provided the technical, psychological, and organizational groundwork for industrialized genocide.47 By drawing on personnel already accustomed to mass murder, by reusing technologies developed for euthanasia, and by adapting bureaucratic routines refined in hospitals and clinics, the Nazi regime transformed domestic racial policy into an international program of annihilation. This progression demonstrates how a system built to kill the disabled could expand into a machinery designed for the destruction of an entire people.

The Holocaust as the Final Expression of Nazi Eugenics

The Holocaust represented the most extreme realization of Nazi eugenic ideology. While antisemitism was always central to Hitler’s worldview, the mechanisms and justifications of mass murder emerged from the regime’s earlier efforts to control reproduction, eliminate perceived hereditary defects, and restructure society along biological lines.48 The language of racial hygiene provided a framework that cast Jews, Roma, and other targeted groups as threats to the genetic survival of the German nation. This fusion of eugenic theory with racial antisemitism transformed prejudice into a state program that sought not merely to segregate or expel unwanted populations but to eradicate them entirely.

During the early years of the war, Nazi policies shifted from forced emigration and ghettoization toward systematic extermination. Medical metaphors dominated the rhetoric of policymakers, who framed Jews as carriers of hereditary degeneracy and disease.49 Himmler, Goebbels, and other leaders repeatedly invoked ideas of infection and contamination to justify increasingly radical actions. These arguments resonated with the eugenic thinking that underpinned earlier legislation, especially the belief that the health of the Volk required eliminating hereditary threats. By portraying genocide as a biological imperative, Nazi leaders aligned mass murder with the state’s purported duty to preserve racial purity.

Eugenic rationales also shaped decisions about who would be targeted and how. Roma communities, labeled by Nazi scholars as “asocial” and genetically inferior, became victims of sterilization and later extermination. Patients with disabilities, already subject to murder under Aktion T4, continued to be killed through starvation, neglect, and injections in hospitals and camps.50 Jews, cast as the primary hereditary enemy, were subjected to intensified measures of segregation, forced labor, and eventually annihilation in extermination centers designed around principles pioneered in the euthanasia program. These overlapping categories reveal how eugenic ideology structured the hierarchy of victims and informed the technological and organizational systems of mass killing.

The scale and structure of the Final Solution were also deeply shaped by the administrative culture developed under earlier eugenic programs. The deportation trains, registration procedures, selection ramps, and cremation facilities resembled expanded versions of the bureaucratic routines tested in T4 institutions.51 Personnel trained in euthanasia centers occupied key roles in extermination camps, bringing with them techniques of deception, rapid killing, and body disposal. This continuity underscores that the Holocaust was not an abrupt departure from Nazi domestic policy but a radical intensification of an already evolving system of state-directed biological violence.

By 1942, the goal of eliminating Jews and other targeted groups had been fully integrated into the administrative machinery of the Third Reich. Wannsee Conference minutes framed extermination as a coordinated effort between civil agencies, the SS, and medical authorities responsible for implementing racial policy.52 In this context, the Final Solution appeared to Nazi officials as the logical culmination of a decade of eugenic legislation, medicalized killing, and racial classification. The Holocaust thus stands as the ultimate expression of the regime’s belief that society could and should be remade through biological purification, a belief that turned pseudoscience into genocide.

Collapse, Exposure, and Global Rejection of Eugenics

The collapse of Nazi Germany in 1945 exposed the full extent of the crimes committed under the banner of racial hygiene. Allied forces entering concentration camps discovered evidence of systematic murder on a scale far beyond what was previously documented. Photographs, transport lists, medical files, and physical remains revealed how deeply eugenic ideology had permeated state institutions.53 The initial shock of these discoveries helped shape postwar understanding of Nazism as a regime built upon pseudoscience and biological determinism, discrediting the idea that hereditary improvement could serve as a legitimate foundation for political or medical authority.

The Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial of 1946–47 played a crucial role in defining the legal and ethical failures of Nazi eugenics. Prosecutors presented detailed evidence of forced sterilization, euthanasia killings, medical experiments, and the use of racial criteria to determine life and death.54 Testimony from physicians and administrators laid bare the professional complicity that had enabled the regime to transform eugenic theory into genocidal practice. The tribunal concluded that Nazi medical policy represented a profound violation of human dignity, and its judgments led to the formulation of the Nuremberg Code, which established principles governing consent and ethical medical research worldwide.

In the broader international community, the association of eugenics with Nazi atrocities resulted in a decisive shift in scientific and political attitudes. Before the Second World War, eugenics movements had influenced policies in many countries, including the United States, Britain, and the Scandinavian nations. After 1945, however, these programs came under intense scrutiny. Scholars, lawmakers, and the public began to question the validity of claims linking heredity to moral or social traits.55 Sterilization statutes remained on the books in some nations for decades, but their intellectual foundation had been irrevocably damaged by the revelation that similar policies had led to mass murder in Germany.

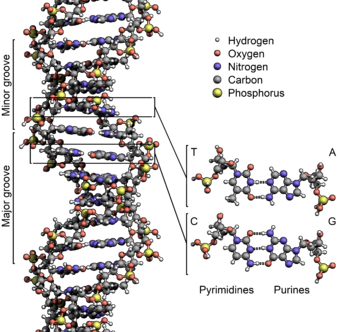

Developments in genetics also contributed to the discrediting of eugenics. The discovery of the structure of DNA in 1953 and subsequent advances in molecular biology demonstrated that hereditary traits did not operate in the simplistic, deterministic manner imagined by eugenic theorists.56 These scientific breakthroughs made clear that complex human behaviors and characteristics could not be reduced to single hereditary factors or eliminated through selective breeding. As genetics matured into a modern field grounded in empirical research and laboratory experimentation, it distanced itself sharply from the racial theories that had dominated earlier decades.

Despite the formal repudiation of eugenics, its legacy continued to influence discussions about human difference and social policy. Historians and ethicists have noted that the assumptions underlying earlier eugenic movements persist in subtler forms, including debates over reproductive rights, genetic screening, and public health interventions.57 The postwar rejection of eugenics therefore represents both a moral reckoning with the crimes of the Nazi regime and an ongoing reminder of the dangers inherent in attempts to use biological theories to shape social hierarchies. The exposure of Nazi atrocities forced the world to confront the catastrophic consequences of merging pseudoscience with state power, reshaping global ethical standards for generations.

Conclusion: The Moral Catastrophe of Scientific Racism

The history of Nazi eugenics demonstrates how pseudoscientific ideas can be transformed into instruments of unprecedented violence when combined with authoritarian power. The regime’s belief in racial hierarchy and hereditary determinism shaped policies that began with sterilization and exclusion but culminated in the systematic murder of millions. Nazi authorities framed their actions as measures necessary to safeguard the health of the German nation, turning medical and administrative institutions into powerful tools of destruction.58 The resulting genocide made clear that ideas about biological improvement, when deployed as state doctrine, can erase ethical boundaries and redefine entire populations as expendable.

The trajectory from sterilization courts to gas chambers underscores the danger of delegating moral authority to scientific claims that lack empirical grounding. Nazi eugenics relied on categories that were presented as objective but were rooted in prejudice, speculation, and ideological conviction. When such categories guided policymaking, they allowed the regime to justify coercion and violence as rational and necessary.59 The willingness of physicians, scientists, and administrators to collaborate in this process illustrates how professional expertise can be manipulated to legitimize actions that violate fundamental human rights.

The postwar world confronted these failures through legal and scientific reforms. The Nuremberg Code established standards for informed consent and ethical medical research, reflecting an international effort to prevent the reemergence of practices that had enabled Nazi atrocities. Advances in modern genetics further undermined the claims of eugenics by demonstrating the complexity of hereditary traits and the inadequacy of simplistic biological explanations for human behavior.60 These developments created a framework for distinguishing legitimate scientific inquiry from ideologically driven misuse of biological concepts.

The legacy of Nazi eugenics remains a powerful warning about the consequences of merging racial ideology with state policy. The Final Solution exposed the catastrophic potential of scientific racism, revealing how quickly societies can descend into violence when they embrace doctrines that classify people according to imagined biological worth. Historians, ethicists, and scientists continue to draw upon this history to emphasize the importance of safeguarding human dignity, resisting biological determinism, and remaining vigilant against efforts to use science as a tool for exclusion or oppression.61 The moral catastrophe of Nazi eugenics thus stands as both a historical lesson and an enduring ethical imperative.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1943), 280–292.

- Sheila Faith Weiss, The Nazi Symbiosis: Human Genetics and Politics in the Third Reich (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 41–53.

- Robert N. Proctor, Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 104–107.

- Henry Friedlander, The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 21–29.

- Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 95–112.

- Christopher R. Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939–March 1942 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 17–25.

- George L. Mosse, The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1964), 1–22.

- Richard Weikart, From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 25–34.

- Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), 49–61.

- Stefan Kühl, The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 23–45.

- Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, 280–292.

- Proctor, Racial Hygiene, 11–28.

- Gretchen E. Schafft, From Racism to Genocide: Anthropology in the Third Reich (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 27–42.

- Michael Wildt, An Uncompromising Generation: The Nazi Leadership of the Reich Security Main Office, trans. Tom Lampert (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009), 54–62.

- Proctor, Racial Hygiene, 57–72.

- Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, 290–305.

- Claudia Koonz, The Nazi Conscience (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), 77–96.

- Karl Binding and Alfred Hoche, Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life, trans. Walter E. Wright (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1992), 24–32.

- Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 34–45.

- Proctor, Racial Hygiene, 104–110.

- Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 46–53.

- Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 95–112.

- Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics, 49–61.

- Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, 402–403.

- Kühl, The Nazi Connection, 23–45.

- Kühl, The Nazi Connection, 45–58.

- Weiss, The Nazi Symbiosis, 53–61.

- Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics, 61–65.

- Weiss, The Nazi Symbiosis, 41–53.

- Proctor, Racial Hygiene, 104–107.

- Weiss, The Nazi Symbiosis, 53–60.

- Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 29–34.

- Michael Burleigh and Wolfgang Wippermann, The Racial State: Germany 1933–1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 52–64.

- Koonz, The Nazi Conscience, 97–105.

- Proctor, Racial Hygiene, 112–121.

- Saul Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume I: The Years of Persecution, 1933–1939 (New York: HarperCollins, 1997), 141–155.

- Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 61–75.

- Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 95–112.

- Michael Burleigh, Death and Deliverance: “Euthanasia” in Germany c. 1900–1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 152–167.

- Burleigh, Death and Deliverance, 189–202.

- Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution, 52–63.

- Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 121–134.

- Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution, 52–63.

- Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 135–144.

- Burleigh, Death and Deliverance, 203–214.

- Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 51–72.

- Proctor, Racial Hygiene, 148–158.

- Saul Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume II: The Years of Extermination, 1939–1945 (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 3–14.

- Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution, 187–200.

- Henry Friedlander, Origins of Nazi Genocide, 221–236.

- Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, 51–72.

- Mark Roseman, The Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution (New York: Picador, 2002), 65–78.

- Michael Berenbaum, The World Must Know (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 112–125.

- United States Military Tribunal, The Doctors Trial (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949), 7–19.

- Philippa Levine, Eugenics: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 95–108.

- James D. Watson, The Double Helix (New York: Scribner, 1968), 123–130.

- Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics, 279–301.

- Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume II, 15–28.

- Proctor, Racial Hygiene, 148–158.

- Watson, The Double Helix, 173–182.

- Levine, Eugenics, 109–119.

Bibliography

- Arad, Yitzhak. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

- Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know: The History of the Holocaust as Told in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

- Binding, Karl, and Alfred Hoche. Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life. Translated by Walter E. Wright. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1992.

- Browning, Christopher R. The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939–March 1942. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

- Burleigh, Michael. Death and Deliverance: “Euthanasia” in Germany c. 1900–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Burleigh, Michael, and Wolfgang Wippermann. The Racial State: Germany 1933–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Friedländer, Saul. Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume I: The Years of Persecution, 1933–1939. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

- Friedländer, Saul. Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume II: The Years of Extermination, 1939–1945. New York: HarperCollins, 2007.

- Friedlander, Henry. The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Translated by Ralph Manheim. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1943 and 1944.

- Kevles, Daniel J. In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Koonz, Claudia. The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Kühl, Stefan. The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Levine, Philippa. Eugenics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Mosse, George L. The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1964.

- Proctor, Robert N. Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988.

- Roseman, Mark. The Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution. New York: Picador, 2002.

- Schafft, Gretchen E. From Racism to Genocide: Anthropology in the Third Reich. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

- United States Military Tribunal. The Doctors Trial: The Medical Case of the United States vs. Karl Brandt et al. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949.

- Watson, James D. The Double Helix. New York: Scribner, 1968.

- Weikart, Richard. From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Weiss, Sheila Faith. The Nazi Symbiosis: Human Genetics and Politics in the Third Reich. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Wildt, Michael. An Uncompromising Generation: The Nazi Leadership of the Reich Security Main Office. Translated by Tom Lampert. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.