In ancient and medieval contexts, blood functioned as a symbolic and material substance that connected the body to cosmological order, ritual boundaries, and spiritual power.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Ideas about “pure blood” appear across a wide arc of ancient and medieval civilizations. They surface in medical treatises, ritual systems, and theological discourses that sought to explain the boundaries between the sacred and the profane, the healthy and the diseased, the morally upright and the dangerously transgressive. These early frameworks did not define purity in racial or hereditary terms. They treated blood as a vital substance with physiological, ritual, and spiritual significance, shaped by cosmology, ethics, and social obligation rather than lineage.1

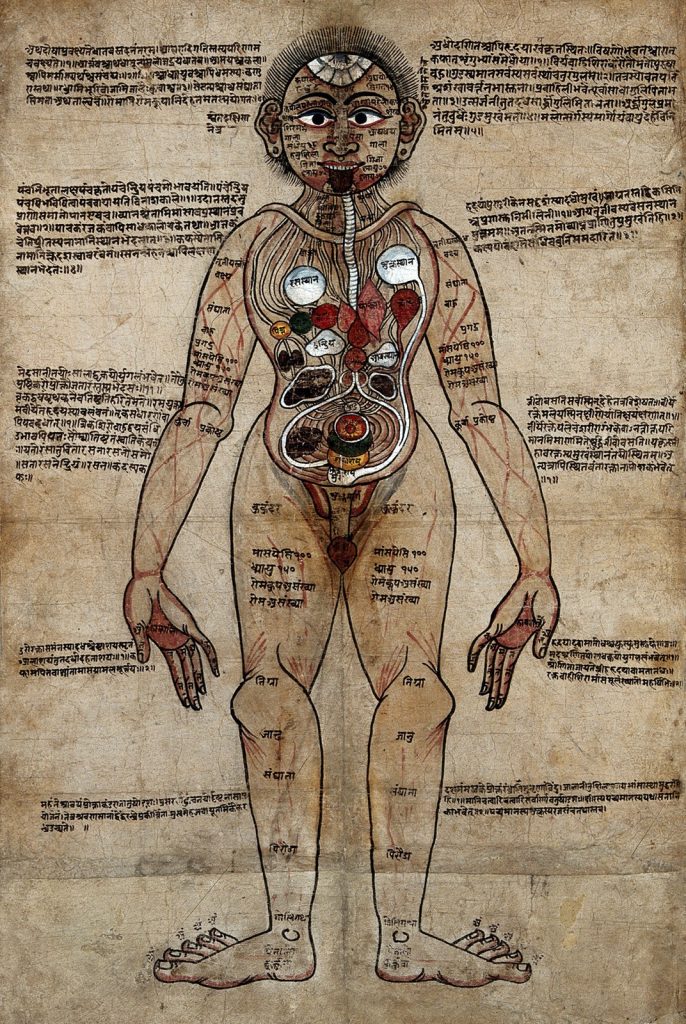

The concept carried different meanings depending on cultural setting. In South Asian medical theory, blood was approached as a bodily humor whose purity was essential to strength and equilibrium, a theme articulated in classical Sanskrit medical works such as the Suśruta Saṃhitā and Caraka Saṃhitā.2 In early Jewish law and its later rabbinic commentaries, blood marked thresholds of life and death and mediated transitions between states of purity and impurity, categories understood as ritual conditions rather than permanent attributes of the person.3 Christian and Islamic traditions often attributed spiritual potency to the blood of martyrs or ascetics, describing it as a sign of fidelity or divine favor. These different meanings shared little conceptual ground beyond the symbolic and moral gravity attributed to blood itself.4

By the later Middle Ages, however, new frameworks emerged that recast blood purity in more rigid terms. In the Iberian Peninsula, statutes of limpieza de sangre developed a hereditary logic that treated impurity as transmitted across generations, applying it to converts from Judaism and Islam and later extending it across colonial societies shaped by conquest and slavery.5 This shift marked a decisive break from earlier understandings. It reinterpreted a long and diverse history of medical, ritual, and spiritual ideas into a quasi-biological doctrine of permanent difference. The evolution of these ideas forms a complex narrative in which ancient symbolic systems were not erased but selectively reframed to serve new political and social hierarchies.6

Ayurvedic Conceptions of “Pure Blood” as Vital Health

Classical Ayurvedic medicine situated blood (rakta) within a broader system of bodily substances whose balance determined vitality, temperament, and resistance to disease. The major Sanskrit medical compendia treat the purity of blood not as a metaphor but as a clinical and physiological condition. In the Suśruta Saṃhitā, blood is described as one of the fundamental bodily elements (dhātus), responsible for nourishment, complexion, and the maintenance of internal heat.7 Disorders of blood, including discoloration, excessive heat, or contamination by waste products, signal deeper disruptions within the body’s networks of channels and humors.8 The Caraka Saṃhitā similarly emphasizes the relationship between digestion, the formation of healthy tissues, and the refinement of blood, treating purity as a measurable indicator of the body’s overall harmony.9

Ayurvedic writers connected the condition of blood to moral and behavioral discipline. The Caraka Saṃhitā links bodily impurities to improper diet, emotional imbalance, and lapses in self-restraint, underscoring how ethical conduct shapes the interior state of the body. These associations reflected a worldview in which the boundary between physiology and morality was porous. The state of one’s blood mirrored the quality of one’s habits and the integrity of one’s relationship to the surrounding natural and social order.10 While these texts do not frame purity in hereditary terms, they do treat blood as a site where the body and cosmos intersect, a substance whose condition reveals the success or failure of an individual’s adherence to Ayurvedic principles.

The emphasis on healthy blood also served a practical medical purpose. Ayurvedic physicians assessed the purity of blood through observation of color, smell, and texture, applying treatments such as purification therapies, dietary regulation, and herbal remedies to restore balance.11 These interventions underscore the central claim of the Ayurvedic medical system that purity is a dynamic quality open to transformation. Unlike later medieval European theories that associated purity with lineage or fixed categories of identity, the Ayurvedic model treated blood as fundamentally responsive. Its purity was not inherited but produced through disciplined living, proper diet, and skilled therapeutic intervention.12

Jewish Ritual Purity and the Theological Meaning of Blood

The ritual system of ancient Judaism treated blood as a powerful marker of life and as a boundary between states of purity and impurity. Biblical law defined impurity not as moral corruption or hereditary stain but as a temporary condition arising from contact with lifeblood, death, or certain bodily processes. Leviticus outlines these transitions with precision, especially in relation to menstruation, childbirth, and corpse impurity.13 These regulations anchor blood within a framework in which holiness depends on a community’s careful navigation of bodily processes that signify nearness to life and its absence.

Rabbinic literature developed these ideas into a highly structured discourse. The Mishnah and Talmud preserve extensive debates on the classification of menstrual blood, the duration of impurity following childbirth, and the procedures required for purification.14 The rabbis also distinguished clearly between ritual impurity (tum’ah) and moral wrongdoing, rejecting any interpretation that linked bodily impurity to a failing of character.15 This conceptual clarity demonstrates the rigor of rabbinic thought and its refusal to conflate temporary ritual states with permanent identity.

Blood also carried symbolic meaning within Jewish theology that extended beyond ritual regulation. It represented life in its most concentrated form, which explains why the consumption of blood was strictly prohibited. The ban, articulated in Leviticus and reaffirmed in rabbinic law, framed blood as a substance reserved for God, reinforcing its status as something both powerful and set apart.16 These prohibitions underscore a broader principle in Jewish thought that life and its markers belong to the divine sphere and must be handled with deliberation and restraint.17

Despite its symbolic weight, Jewish law never interpreted blood purity in hereditary or genealogical terms. Ritual impurity was neither inherited nor permanent. It could be removed through washing, immersion, or the passage of time, and it did not define a person’s worth or communal standing. This distinction makes Jewish purity law fundamentally different from later European systems that treated impurity as a biological condition transmitted across generations.18

Blood as Spiritual Power: Martyrdom, Sanctity, and the Moral Body

The religious cultures of late antiquity and the medieval world invested blood with spiritual meaning that extended far beyond ritual regulation. Early Christian writers described the blood of martyrs as a visible sign of fidelity, interpreting it as both witness and offering. In these traditions, martyrdom was not simply an act of suffering but an expression of the believer’s full participation in the redemptive narrative of Christ, whose own blood was understood to effect salvation.19 Accounts of martyrdom circulated widely, shaping Christian ideas about the moral potency of bodily substances and reinforcing the belief that the shedding of blood for faith transformed the individual into a figure of sanctity.

These notions continued to evolve in medieval Christian practice. The cult of saints emphasized the spiritual force of bodies that had displayed extraordinary virtue, and relics associated with blood were attributed with healing and intercessory powers.20 Hagiographical texts often portrayed the blood of saints as uncorrupted or miraculously preserved, treating it as tangible evidence of divine favor.21 These accounts encouraged the idea that spiritual purity could manifest physically, especially in individuals whose lives had been marked by ascetic discipline or public testimony. The connection between bodily substance and moral excellence became a hallmark of medieval Christian piety.

Islamic tradition similarly regarded martyrdom (shahāda) as an act of profound religious significance, though its framing differed from Christian narratives. Classical hadith collections describe the martyr as forgiven of sins at the moment of death, and some accounts emphasize that the body of the martyr will bear the scent of musk rather than decay.22 Scholars of early Islamic thought note that the spiritual power attributed to martyrdom reflects a theology in which bodily integrity after death signifies divine acknowledgment of a life lived in accordance with God’s will.23 These traditions created their own vocabulary of purity grounded in steadfastness and righteous intention rather than inherited condition.

The association between blood and spiritual power was further strengthened by the emphasis on ascetic self-discipline in both Christian and Islamic traditions. Monastic writings frequently described the body as a landscape shaped by moral struggle, and even when blood was not shed through martyrdom, its purity could be understood metaphorically. Authors such as the monastic fathers of the Egyptian desert linked inner transformation to the refinement of bodily impulses, suggesting that sanctity was visible in the disciplined body.24 Although blood itself is not always invoked directly, the symbolic relationship between bodily substance and spiritual condition underpinned these moral frameworks.

These religious traditions therefore treated blood as a substance capable of reflecting states of spiritual perfection or divine proximity, but they did not interpret purity as a function of lineage or ancestry. Purity was acquired through conduct and devotion, not inherited through birth. The link between blood and sanctity remained rooted in personal transformation, moral achievement, and divine recognition.25 This understanding stands in sharp contrast to later systems that framed impurity as a permanent and genealogical marker.

Purity, Lineage, and Social Hierarchies within Jewish Communities

Mediterranean Jewish communities of the medieval period lived within cultural environments that placed significant emphasis on lineage, ancestry, and inherited status. These surrounding norms sometimes influenced internal Jewish social structures, especially in regions where Christian or Islamic elites used genealogical claims to assert distinction. Although Jewish law rejected the idea of hereditary ritual impurity, some Jewish groups developed internal preferences for certain family lines, treating noble or priestly descent as a marker of elevated status.26 These distinctions were not framed as biological purity but as social capital shaped by family reputation and communal memory.

Sephardic communities of Iberia and the western Mediterranean provide some of the clearest evidence of these dynamics. Documents from medieval Jewish courts and communal registers record disputes over marriage arrangements, inheritance, and family honor in which lineage played a central role.27 Families associated with ancient priestly descent or long-established communal leadership often guarded their status closely, sometimes discouraging marriage with families of less recognized standing.28 These concerns reflected broader medieval patterns in which lineage functioned as a resource for organizing social hierarchy, not as a claim about the purity or impurity of blood itself.

In some cases, external pressures intensified these internal hierarchies. The rise of Christian genealogical scrutiny in Iberia, especially during the fifteenth century, placed Jewish families under increasing observation. While Jews did not adopt the Christian doctrine of hereditary impurity, they were aware that Christian authorities evaluated ancestry in ways that could have material consequences for converts and their descendants.29 Scholars have argued that this external surveillance sometimes encouraged Jewish elites to articulate their own lineage distinctions more sharply, partly to maintain communal cohesion and partly to negotiate status within a broader environment preoccupied with ancestry.30 These developments demonstrate how external ideologies could shape internal social dynamics without altering core theological principles.

Even where lineage distinctions emerged, they did not represent a Jewish doctrine of purity of blood, nor were they universal across Jewish communities. Jewish law continued to treat ritual impurity as temporary and unrelated to ancestry, and many communities actively resisted imposing genealogical hierarchies.31 The selective and localized nature of these practices reveals the complex interplay between inherited social structures, communal identity, and the pressures of the surrounding societies in which Jews lived.

The Iberian Transformation: Limpieza de Sangre and Proto-Racial Ideology

The fifteenth century in the Iberian Peninsula marked a turning point in the history of blood purity. Concepts that had once belonged to theological and ritual discourse were reformulated into legal and social categories that treated impurity as a hereditary condition. The earliest statutes of limpieza de sangre appeared in the 1449 Sentencia-Estatuto of Toledo, which excluded conversos from municipal offices on the grounds that their ancestry rendered them unfit for public trust.32 This new logic departed sharply from medieval Christian theology, which had emphasized the possibility of spiritual renewal through conversion. Instead, these statutes framed impurity as an indelible quality transmitted through generations and unaffected by Christian faith.

Religious institutions played a central role in expanding this system. Cathedral chapters, monastic orders, confraternities, and universities adopted their own purity statutes during the sixteenth century, often requiring applicants to prove Old Christian lineage extending back several generations.33 These requirements created a bureaucratic culture of genealogical investigation that transformed personal identity into an object of archival scrutiny.34 The process reinforced the idea that ancestry defined moral and religious trustworthiness, embedding proto-racial thinking within institutions that shaped civic and ecclesiastical life.

The statutes also recast social relations across Iberian communities. Conversos, many of whom were practicing Christians for generations, encountered increasing restrictions on marriage, employment, and public office.35 Moriscos, descended from Muslim converts, faced similar and sometimes harsher constraints. The logic of hereditary impurity placed these groups outside the boundaries of full Christian belonging, not because of their beliefs or behavior but because of an imagined stain in the bloodline.36 This ideology reinterpreted religious difference as biological difference, narrowing the space for assimilation and redefining the criteria for social inclusion.

Debate over these statutes arose almost immediately. Some theologians argued that the statutes contradicted foundational Christian teachings about baptism and universal redemption, while others defended them as necessary for maintaining social order.37 Humanists and jurists criticized the genealogical tests as unreliable and prone to corruption, yet the statutes remained influential well into the seventeenth century.38 These debates reveal both the ideological instability of limpieza de sangre and its capacity to reshape Iberian society despite its theological contradictions.

The Iberian model eventually extended far beyond the peninsula. Its definitions of hereditary impurity provided a template for emerging colonial hierarchies in the Americas, where Spanish administrators created new classifications to manage diverse populations.39 Although colonial systems differed from their Iberian predecessors, they drew upon the same underlying belief that ancestry could determine social, legal, and spiritual worth. The transformation of purity into genealogy therefore represents one of the clearest early examples of the shift from religious to racial thinking in the late medieval and early modern world.40

Colonial Transmission: Blood Purity in the Americas and Beyond

The Iberian doctrine of hereditary impurity did not remain confined to Spain. As the Spanish and Portuguese empires expanded into the Americas, the logic of limpieza de sangre traveled with administrators, clergy, and settlers who carried with them expectations about the relationship between ancestry and social worth. Colonial officials quickly adapted these ideas to the diverse populations they encountered in the New World. In many regions, status depended on proof of Old Christian descent, and converso ancestry could limit access to offices, guilds, or religious positions just as it had on the Iberian Peninsula.41 The principle that lineage determined civic reliability became woven into the administrative fabric of colonial government.

In the Americas, these ideas intersected with the realities of conquest, enslavement, and intermarriage. Spanish administrators confronted societies in which Indigenous peoples and Africans held central roles in economic life, and they developed new classifications that merged Iberian genealogical concerns with emerging colonial categories.42 The resulting casta system distinguished individuals by degrees of European, Indigenous, and African ancestry, creating a hierarchy grounded in perceived biological difference.43 Although these classifications were not identical to Iberian statutes, they drew from the same assumption that ancestry could be used to define legal privileges and social boundaries. The emphasis on inherited identity marked a significant departure from earlier medieval frameworks that treated religious difference as changeable.

Colonial secular and ecclesiastical institutions reinforced these new hierarchies. Bishops required evidence of purity of lineage for ordination, and religious orders often screened applicants for ancestry associated with conversos or non-European populations.44 Civil authorities sometimes required genealogical investigations for military appointments, civic offices, and marriage dispensations. These practices created a bureaucratic culture that relied on archival records, witness testimony, and administrative inquiry to classify populations.45 The process extended the reach of Iberian purity statutes while adapting them to the demographic complexity of colonial society.

The ideology of hereditary impurity also shaped everyday social relations. Restrictions on marriage across casta categories, though not always enforced, reflected widespread concerns about preserving social standing through control of family lineage.46 Ideas about blood purity influenced the formation of urban elites who cultivated genealogies linking themselves to early European settlers, even as many had mixed ancestry.47 This selective memory allowed local elites to assert political authority and cultural distinction using claims about pure descent that echoed Iberian precedents. The result was a social landscape in which ancestry functioned both as a legal marker and as a narrative tool for constructing elite identity.

These colonial developments reflected a broader shift in which purity became linked to racialized conceptions of difference. The logic of limpieza de sangre, conditioned by Iberian anxieties over converso and morisco ancestry, combined with colonial systems of labor and domination to produce new hierarchies that treated identity as fixed and inheritable.48 While the mechanisms and categories differed across regions, the underlying belief that blood could carry impurity or inferiority across generations marked one of the earliest sustained articulations of racial thinking in the Atlantic world.

Conclusion: From Ritual Substance to Racial Category

The long history of blood purity reveals that the concept did not originate as a biological marker or a theory of inherited difference. In ancient and medieval contexts, blood functioned as a symbolic and material substance that connected the body to cosmological order, ritual boundaries, and spiritual power. Ayurvedic physicians treated its purity as a sign of physiological balance, while Jewish law understood blood as a marker of life that required careful regulation but did not define identity or lineage. Early Christian and Islamic traditions used blood to signify sanctity, martyrdom, and moral transformation. These frameworks approached blood as dynamic and responsive, shaped by conduct, ritual, and spiritual striving rather than ancestry.49

The shift toward hereditary purity began not in antiquity but in late medieval Iberia, where social, political, and religious pressures converged. The statutes of limpieza de sangre reframed purity as a genealogical condition that conversion could not alter. In this new model, impurity traveled through generations as an indelible quality attributed to entire categories of people.50 This transformation occurred alongside intensified anxieties about religious conformity, the consolidation of state power, and the development of institutions that relied on documentation and surveillance. The result was a system that treated ancestry as the determinant of trustworthiness, loyalty, and moral standing.51

When these ideas entered the colonial world, they became intertwined with systems of conquest, enslavement, and labor exploitation. The Iberian doctrine of hereditary impurity helped shape the development of casta categories, which treated identity as a matter of quantifiable ancestry. Although colonial societies differed across regions, they shared a reliance on the notion that blood could encode difference in ways that justified political domination and social hierarchy.52 This expansion marked one of the earliest sustained attempts to translate symbolic and theological concepts of purity into frameworks that approached racial classification.

Across these diverse contexts, the evolution of blood purity demonstrates how symbolic meanings can be reinterpreted to serve new social realities. Ancient and medieval traditions saw purity as contingent, achievable, and tied to ritual or moral life. Iberian and colonial systems recast purity as fixed, hereditary, and exclusionary.53 The transformation from substance to lineage, and from ritual to race, illustrates how concepts rooted in cosmology and spirituality can be co-opted into powerful tools of classification and control. It is in this reframing that the modern logic of race (constructed, imposed, and naturalized) begins to take shape.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London: Routledge, 1966).

- The Suśruta Saṃhitā, ed. and trans. K. R. Srikantha Murthy, 3 vols. (Varanasi: Chaukhambha Orientalia, 1999).

- The Caraka Saṃhitā, ed. and trans. Priya Vrat Sharma, 4 vols. (Varanasi: Chaukhambha Orientalia, 1981).

- Jonathan Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- Candida R. Moss, The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom (New York: HarperOne, 2013); Tarif Khalidi, Images of Muhammad (New York: Doubleday, 2009).

- Albert A. Sicroff, Les controverses des statuts de “pureté de sang” en Espagne du XVe au XVIIe siècle (Paris: Didier, 1960); David Nirenberg, Communities of Violence: Persecution of Minorities in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996).

- The Suśruta Saṃhitā, vol. 1, 81–84.

- The Suśruta Saṃhitā, vol. 1, 85–90.

- The Caraka Saṃhitā, vol. 1, 336–340.

- The Caraka Saṃhitā, vol. 1, 252–255.

- The Suśruta Saṃhitā, vol. 2, 112–120.

- Kenneth G. Zysk, Asceticism and Healing in Ancient India: Medicine in the Buddhist Monastery (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 32–35.

- Leviticus 12–15, in The Jewish Study Bible, ed. Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

- The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933), Nidda 1–10.

- Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism, 23–31.

- Leviticus 17:10–14, in The Hebrew Bible, ed. Berlin and Brettler.

- Jacob Milgrom, Leviticus 17–22, Anchor Yale Bible Commentary (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 1480–1485.

- Isaiah M. Gafni, “Ritual Purity and the Jewish Community in Antiquity,” in The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 4, ed. Steven T. Katz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 810–815.

- Tertullian, Apologeticus, trans. T. R. Glover, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931), 305–309.

- Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 86–92.

- Hippolyte Delehaye, The Legends of the Saints (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1962), 45–48.

- Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, Book 52 (Jihad), Hadith 72; M. Muhsin Khan, trans., The Translation of the Meanings of Sahih Al-Bukhari (Riyadh: Darussalam, 1997).

- Tarif Khalidi, Images of Muhammad (New York: Doubleday, 2009), 92–96.

- Benedicta Ward, The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, Cistercian Studies 59 (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1975), 12–15.

- David Brakke, Athanasius and the Politics of Asceticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 128–131.

- Hayim H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976), 383–389.

- Mark R. Cohen, Jewish Self-Government in Medieval Egypt (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), 112–118.

- Yom Tov Assis, The Golden Age of Aragonese Jewry (Portland: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 1995), 143–150.

- David Nirenberg, Communities of Violence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 204–212.

- Jonathan Ray, After Expulsion: 1492 and the Making of Sephardic Jewry (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 22–28.

- Isaiah M. Gafni, “Communal Structures and Legal Authority,” in The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 6, ed. Robert Chazan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 512–517.

- Albert A. Sicroff, Les controverses des statuts de “pureté de sang”, 35–41.

- José Miguel López Villalba, “Limpieza y salubridad urbana en Castilla en el tránsito de la Edad Media a la Moderna,” Historia. Instituciones. Documentos 48 (2021): 255-284.

- Francisco Márquez Villanueva, “Los estatutos de limpieza de sangre: Definición de un problema,” in Orígenes de la Inquisición Española, ed. Ángel Alcalá (Barcelona: Ariel, 1979), 303–326.

- Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965), 118–125.

- Nirenberg, Communities of Violence, 226–232.

- Adriano Prosperi, Tribunali della coscienza: Inquisitori, confessori, missionari (Turin: Einaudi, 1996), 145–151.

- Stefania Pastore, Il vangelo e la spada (Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2003), 201–209.

- María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 55–63.

- Miriam Eliav-Feldon, Benjamin Isaac, and Joseph Ziegler, eds., The Origins of Racism in the West (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 229–245.

- María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions, 55–58.

- Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, Puritan Conquistadors (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006), 112–115.

- Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 1–9.

- Patricia Seed, Ceremonies of Possession in Europe’s Conquest of the New World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 142–146.

- David Tavárez, The Invisible War (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011), 83–88.

- National Research Council, Hispanics and the Future of America, (Washington: National Academies Press), 2006.

- Kathryn Burns, Into the Archive: Writing and Power in Colonial Peru (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 52–59.

- Eliav-Feldon, Isaac, and Ziegler, eds., The Origins of Racism in the West, 229–245.

- Douglas, Purity and Danger, 41–57.

- Sicroff, Les controverses des statuts de “pureté de sang”, 35–49.

- Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition, 118–132.

- Martínez, Genealogical Fictions, 55–72.

- Benjamin Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 318–330.

Bibliography

- Assis, Yom Tov. The Golden Age of Aragonese Jewry. Portland: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 1995.

- Ben-Sasson, Hayim H. A History of the Jewish People. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Berlin, Adele, and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds. The Jewish Study Bible. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Brakke, David. Athanasius and the Politics of Asceticism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Brown, Peter. The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

- Burns, Kathryn. Into the Archive: Writing and Power in Colonial Peru. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

- Cañizares-Esguerra, Jorge. Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550–1700. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.

- Cohen, Mark R. Jewish Self-Government in Medieval Egypt: The Origins of the Office of Head of the Jews, 997–1172. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

- Danby, Herbert, trans. The Mishnah. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933.

- Delehaye, Hippolyte. The Legends of the Saints. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1962.

- Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge, 1966.

- Eliav-Feldon, Miriam, Benjamin Isaac, and Joseph Ziegler, eds. The Origins of Racism in the West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Gafni, Isaiah M. “Communal Structures and Legal Authority.” In The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 6, edited by Robert Chazan, 512–517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- —- “Ritual Purity and the Jewish Community in Antiquity.” In The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 4, edited by Steven T. Katz, 810–815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Isaac, Benjamin. The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Kamen, Henry. The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965.

- Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Khalidi, Tarif. Images of Muhammad. New York: Doubleday, 2009.

- Klawans, Jonathan. Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Martínez, María Elena. Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

- Miguel López Villalba, José. “Limpieza y salubridad urbana en Castilla en el tránsito de la Edad Media a la Moderna.” Historia. Instituciones. Documentos 48 (2021): 255-284.

- Milgrom, Jacob. Leviticus 17–22. Anchor Yale Bible Commentary. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Moss, Candida R. The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. New York: HarperOne, 2013.

- Márquez Villanueva, Francisco. “Los estatutos de limpieza de sangre: Definición de un problema.” In Orígenes de la Inquisición Española, edited by Ángel Alcalá, 303–326. Barcelona: Ariel, 1979.

- National Research Council. Hispanics and the Future of America. Washington: National Academies Press, 2006.

- Nirenberg, David. Communities of Violence: Persecution of Minorities in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Pastore, Stefania. Il vangelo e la spada: L’Inquisizione di Castiglia e i suoi critici (1530–1598). Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2003.

- Prosperi, Adriano. Tribunali della coscienza: Inquisitori, confessori, missionari. Turin: Einaudi, 1996.

- Seed, Patricia. Ceremonies of Possession in Europe’s Conquest of the New World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Sharma, Priya Vrat, ed. and trans. The Caraka Saṃhitā. 4 vols. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Orientalia, 1981.

- Sicroff, Albert A. Les controverses des statuts de “pureté de sang” en Espagne du XVe au XVIIe siècle. Paris: Didier, 1960.

- Srikantha Murthy, K. R., ed. and trans. The Suśruta Saṃhitā. 3 vols. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Orientalia, 1999.

- Tavárez, David. The Invisible War: Indigenous Devotions, Discipline, and Dissent in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.

- Tertullian. Apologeticus. Translated by T. R. Glover. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931.

- Ward, Benedicta. The Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Cistercian Studies 59. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1975.

- Zysk, Kenneth G. Asceticism and Healing in Ancient India: Medicine in the Buddhist Monastery. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.