Intelligence is best understood not as a fixed or isolated attribute but as a complex, evolving concept shaped by cultural values, scientific methods, and ethical commitments.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Efforts to understand and evaluate human intelligence long predate the scientific systems that dominate modern psychology. Ancient societies developed rich philosophical and administrative traditions for identifying talent and judging intellectual capability, but they did so without numerical scores or standardized instruments. Intelligence was treated as a constellation of qualities expressed through learned skill, cultivated discipline, and philosophical disposition rather than a fixed attribute that could be measured and ranked. These early frameworks reveal how deeply conceptions of human ability were embedded within cultural, moral, and institutional contexts.1

The shift toward quantification emerged only in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when new scientific and statistical methods sought to transform intellectual performance into measurable data. Researchers attempted to define intelligence as a single, general capacity and to evaluate it through controlled testing.2 This movement produced the first psychometric scales, mass testing programs, and ultimately the intelligence quotient, all of which profoundly shaped educational systems, military organization, and social policy. Yet the transition from ancient qualitative judgments to modern numerical assessments was neither linear nor uncontroversial. It unfolded within debates over heredity, environment, culture, and the very nature of the human mind.3

These developments produced possibilities and dangers in equal measure. Standardized tests made it possible to identify individuals needing support and to study patterns of cognitive development, but they also became tools for exclusion and hierarchy when appropriated by ideologies such as eugenics and racially restrictive immigration policy.4 The history of intelligence measurement therefore reflects not only changing scientific techniques but also shifting ethical boundaries and cultural assumptions about human difference.5

What follows traces that long trajectory from ancient China and Greece to the psychometric systems of the twenty-first century, examining how different civilizations defined intellectual ability, why they sought to assess it, and how those assessments shaped social life. It argues that what societies choose to measure, and how they choose to measure it, reveals as much about their values and anxieties as it does about the human mind itself.6

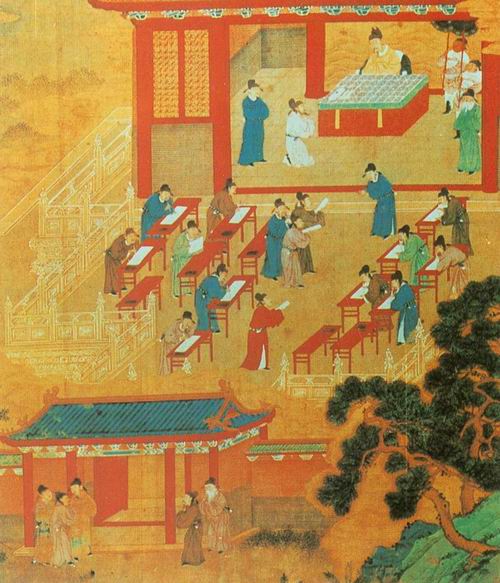

Ancient China: Civil Examinations and Early Cognitive Assessment

The Chinese civil service examination system represents one of the earliest and most extensive institutional efforts to evaluate human ability. Although the legendary origins of the kejue system are often linked to remote antiquity, its documented development accelerated under the Han dynasty, when examinations became a tool for selecting officials based on demonstrated knowledge and cultivated skill. Candidates were expected to master the “Six Arts,” which included music, archery, horsemanship, writing, arithmetic, and the rites, a curriculum that treated intellectual excellence as inseparable from moral discipline and technical competence.7 These skills reflected elite ideals rather than innate mental capacity, revealing how intelligence was embedded within broader cultural expectations of refinement and self-cultivation.

By the Sui and Tang dynasties, civil examinations had expanded to include written assessments in subjects such as law, geography, and classical literature.8 These examinations demanded not only memorization and textual mastery but also the ability to compose essays and policy arguments, demonstrating an early interest in evaluating cognitive flexibility, rhetorical skill, and administrative reasoning. The shift from aristocratic recommendation to merit-based competition marked a profound change in how the state understood aptitude. It privileged demonstrated achievement over lineage, creating an institutional model in which intellectual skill could, at least in principle, be cultivated by any qualified learner.

The sophistication of Chinese thinking about cognition is further illustrated by Liu Xie, a sixth-century scholar who proposed an early psychological assessment in his treatise Wenxin diaolong. Liu suggested evaluating an individual’s ability to perform multiple tasks simultaneously as a way of assessing mental agility.9 While his proposal served literary and rhetorical aims rather than formal testing, it reveals an awareness that cognitive abilities could be observed, compared, and described. The emphasis remained qualitative, focusing on attentiveness, composure, and responsiveness rather than quantifiable traits.

Although Chinese examinations were rigorous, they did not aim to measure innate intelligence or to reduce intellectual capacity to a single metric. Their purpose was to assess scholarly preparation, moral rectitude, and administrative judgment, all rooted in a worldview that linked knowledge to ethical formation and social responsibility.10 This orientation distinguishes ancient Chinese practices from later scientific attempts to quantify cognitive ability. It illustrates how early systems of evaluation were shaped not by psychometric theory but by the cultural and political goals of the state.

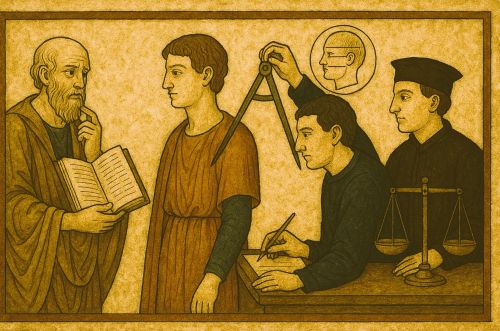

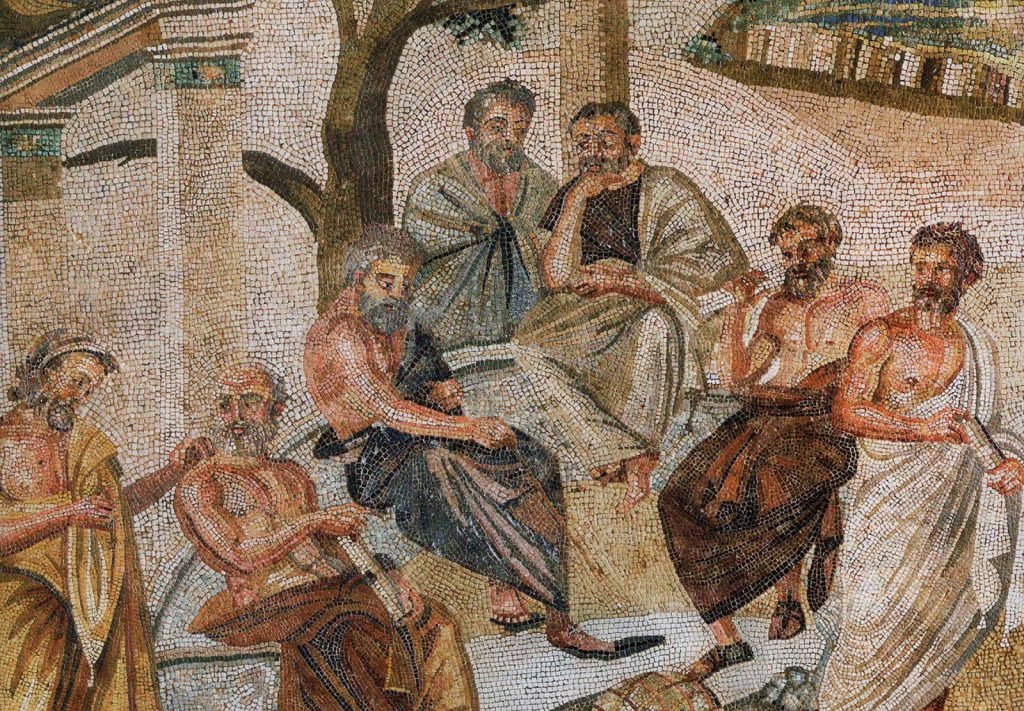

Ancient Greece: Philosophical Theories of Reason and Cognitive Virtue

Greek philosophers developed intricate frameworks for understanding human intelligence, but they approached the subject through qualitative distinctions rather than empirical measurement. Plato distinguished between forms of rational activity that operated through different modes of apprehending truth. In works such as the Republic and the Phaedrus, he contrasted discursive reasoning, which proceeds step by step through logical inference, with intuitive knowledge that grasps fundamental truths directly.¹¹ These categories reflected an interest in how the mind engages with reality rather than an attempt to determine cognitive ability through standardized criteria.

This philosophical orientation shaped Greek discussions of intellectual excellence. Intelligence was treated as a virtue cultivated through education, moral training, and participation in civic life.12 The philosophical schools of Athens emphasized dialectical practice, ethical formation, and mastery of abstract reasoning, all of which were understood as markers of an educated mind. These practices aimed to nurture the capacity for judgment and discernment rather than to assess individuals through structured tasks or numerical benchmarks. The emphasis remained on developing the mind toward its highest potential, not on ranking individuals according to cognitive performance.

Aristotle, though concerned with categorizing mental faculties, likewise approached intelligence as a set of capabilities expressed through practical deliberation, theoretical contemplation, and moral choice. His discussions in the Nicomachean Ethics and the De Anima identified different kinds of intellectual virtues, each associated with specific forms of reasoning.13 Yet these classifications were descriptive and analytical, concerned with the structure of human cognition rather than its measurement. No effort was made to create tests, scales, or comparative metrics, and the idea of quantifying intellectual difference would have been incompatible with the Greek emphasis on virtue, education, and the pursuit of the good.

The Greek tradition therefore offered a sophisticated account of human cognition, but one that remained rooted in philosophy rather than empirical inquiry. Intelligence was defined through qualities of thought, moral character, and philosophical engagement, not through measurable performance.14 This orientation stands in sharp contrast to the later scientific movements that sought to turn cognitive ability into a quantifiable and standardized attribute.

The Nineteenth Century and the Birth of Scientific Measurement

The nineteenth century introduced a new scientific ambition: to transform intelligence from a philosophical or administrative concept into a measurable trait. This transformation was rooted in developments in statistics, evolutionary theory, and anthropology, all of which encouraged researchers to compare individuals systematically. Francis Galton emerged as a central figure in this movement. Inspired by his interpretation of hereditary genius, he argued that mental ability was an inherited trait that could be revealed through empirical testing.15 His research sought to identify correlations between intelligence and physiological characteristics, marking one of the earliest attempts to approach the mind through quantifiable data.

Galton’s experimental methods reflected both the innovation and limitations of early psychometrics. He established an Anthropometric Laboratory in London where he measured reaction time, grip strength, visual acuity, and other physical and sensory traits in thousands of volunteers.16 Galton believed these measures reflected the speed and efficiency of the nervous system and thus provided indirect indicators of intellectual capacity. Although his work helped introduce statistical tools such as correlation and regression into the study of human ability, the data he collected ultimately failed to support his claims. Researchers found no meaningful relationship between the physiological variables he measured and the intellectual qualities he hoped to capture.17

These shortcomings did not diminish the broader momentum toward scientific assessment. The nineteenth century produced growing confidence that intelligence could be quantified and compared through systematic observation.18 Debates intensified over which traits should be measured, how to measure them, and whether intelligence represented a single capacity or a collection of abilities. Galton’s emphasis on heredity also helped shape early discussions about the biological basis of intellectual differences, influencing later movements that used scientific authority to justify social hierarchies. The interplay between statistical innovation and ideological assumption became a defining feature of early intelligence research.

Despite its flaws, this early period laid the groundwork for the first practical systems of intelligence testing in the early twentieth century. It defined the categories, methods, and scientific language through which researchers approached mental ability.19 The nineteenth century thus marks a transitional moment when intelligence began to shift from a philosophical idea and administrative criterion to a scientific object of study, setting the stage for

the emergence of structured psychological tests.

The Binet-Simon Scale and the Modern Foundations of Intelligence Testing

The first practical intelligence test emerged not from hereditarian theory but from concerns within the French educational system. In 1904, the French Ministry of Public Instruction commissioned Alfred Binet to develop a method for identifying schoolchildren who required specialized instruction. Binet rejected the assumption that intelligence was fixed or biologically determined. Instead, he approached mental ability as a set of functional skills that could be observed and analyzed.20 His goal was to help teachers support students who struggled in traditional classrooms, not to classify individuals permanently or rank them across society.

Working with his collaborator Théodore Simon, Binet developed a series of tasks designed to assess judgment, attention, memory, and problem-solving.21 The resulting Binet-Simon Scale, published in 1905 and revised in 1908 and 1911, represented a major departure from earlier speculative or physiological approaches. The test consisted of everyday activities such as repeating digits, naming objects, defining words, and solving simple reasoning problems. These tasks reflected Binet’s belief that intelligence involved practical reasoning and adaptive behavior. The scale provided a structured way to observe how children performed cognitive tasks appropriate for their age.

A core innovation of the Binet-Simon Scale was the introduction of “mental age.” Instead of treating intelligence as a fixed trait, Binet and Simon compared a child’s performance to the average performance of children in different age groups.22 A child whose test results aligned with those of older children could be said to have a higher mental age, while a child performing below age-level expectations might require additional support. This concept allowed educators to identify students whose cognitive development differed from chronological expectations without assuming biological inferiority or permanence.

Binet emphasized that his test was a diagnostic tool, not a measure of intrinsic worth. He warned explicitly against using the scale to categorize individuals rigidly or to conclude that intelligence was immutable.23 His writings stressed that intellectual ability could be cultivated through education, practice, and social environment. This perspective sharply contrasted with later uses of intelligence testing, particularly in the United States, where the focus shifted toward ranking individuals through a single numerical index. The original purpose of the Binet-Simon Scale was educational intervention, not social stratification.

The Binet-Simon Scale thus laid the foundation for modern psychometrics while retaining a cautious and flexible understanding of human cognition. It demonstrated that structured tasks could provide meaningful information about cognitive development, yet it was rooted in a philosophy that emphasized growth, variability, and the importance of context.24 The later history of intelligence testing would depart significantly from Binet’s intentions, but his work remains a landmark achievement in the systematic study of mental ability.

The IQ Concept and American Adaptation (1912–1916)

The next major shift in intelligence testing occurred when German psychologist William Stern introduced the term “intelligence quotient” to describe a numerical relationship between mental age and chronological age. Stern argued that dividing mental age by chronological age and multiplying by one hundred produced a stable index that could be used to compare individuals across developmental stages.25 His formulation transformed Binet’s developmental observations into a standardized metric, contributing to the emergence of intelligence as something that could be quantified, ranked, and compared. This shift aligned with broader trends in psychology that sought to create measurable constructs grounded in statistical analysis.

Lewis Terman at Stanford University expanded the influence of Stern’s ideas by revising the Binet-Simon Scale for American use. His 1916 Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale reorganized test items, introduced new tasks, and applied Stern’s IQ formula directly.26 Terman’s adaptation reflected his belief that intelligence was largely hereditary and stable across a person’s life, a position that differed significantly from Binet’s emphasis on cognitive development and educational intervention. He promoted the Stanford-Binet as a tool for identifying both giftedness and deficiency, helping to popularize the single IQ score as the dominant measure of human cognitive ability in the United States.

The American adoption of IQ coincided with a growing enthusiasm for standardized testing across educational and administrative institutions.27 The appeal of a numerical score lay in its seeming objectivity. Teachers, administrators, and policymakers could compare individuals quickly and, ostensibly, without subjective bias. Yet this new framework also risked reducing complex cognitive processes to a single dimension. Researchers began to debate whether one number could adequately represent the diversity of human intellectual skills. The reliance on IQ also obscured the influences of environment, culture, and opportunity on test performance, foreshadowing later critiques of psychometrics.

Despite these concerns, the IQ concept shaped much of twentieth-century thought about intelligence. Its simplicity facilitated widespread adoption, and its statistical foundation aligned with prevailing scientific approaches.28 Terman’s work helped institutionalize intelligence testing in schools, universities, and government agencies, embedding the IQ framework deeply into American psychological practice. At the same time, the assumptions underpinning early IQ theory, particularly regarding heredity and fixed ability, set the stage for both scientific advances and significant ethical problems that would emerge in subsequent decades.

Mass Testing and the Military: World War I and the Rise of Psychometrics

World War I marked a major expansion in the scale and ambition of intelligence testing. Under the direction of psychologist Robert Yerkes, the U.S. Army sought a rapid, standardized method for classifying recruits and assigning them to appropriate roles. Yerkes and his colleagues designed two tests: the Army Alpha for literate recruits and the Army Beta for those who were illiterate or non-English speakers.29 These assessments represented a dramatic increase in the use of psychological testing as a tool of state administration, demonstrating that intelligence evaluation could be deployed across massive and diverse populations. The program ultimately tested more than one million men, far exceeding any previous effort in the history of psychometrics.

The scale of the Army testing program introduced new methodological challenges. Recruit camps varied widely in conditions, administration was often rushed, and many examinees lacked familiarity with the cultural assumptions embedded in the test items.30 The Army Beta attempted to address linguistic diversity by relying on pictorial tasks, but even these required prior exposure to American cultural forms. Despite these limitations, military officials viewed the testing program as a success, in part because it provided a sense of scientific legitimacy to decisions about personnel placement. The results were influential not because of their precision but because they demonstrated the perceived utility of standardized cognitive assessment.

The Army tests also helped move intelligence testing beyond educational and clinical settings into broader public life. After the war, psychologists promoted the Alpha and Beta tests as evidence that large-scale mental measurement was feasible and valuable.31 Schools, employers, and social service agencies began adopting standardized testing as a way to classify individuals and allocate resources. The appeal of quantitative assessment was heightened by the growing prestige of scientific management and the belief that objective measurement could improve institutional efficiency. These developments amplified the authority of psychometric methods and encouraged further refinement of testing tools.

Yet the wartime testing program exposed significant concerns about validity and fairness. Analysts soon noted that test performance correlated strongly with years of schooling, socioeconomic background, and English-language proficiency rather than innate cognitive ability.32 These critiques highlighted the cultural and educational biases embedded within the tests and foreshadowed later debates about the relationship between environment and measured intelligence. Despite these issues, the Army Alpha and Beta left a lasting institutional and conceptual legacy, shaping the trajectory of intelligence testing throughout the twentieth century.

The Development of Modern Intelligence Scales: Wechsler and Beyond

By the mid-twentieth century, psychologists increasingly questioned whether a single numerical score could capture the complexity of human intelligence. David Wechsler emerged as one of the most influential critics of the unitary IQ concept. Working as a clinical psychologist in New York, he observed that individuals often showed uneven cognitive profiles, with strengths in some areas and weaknesses in others.33 This insight led him to design intelligence scales that divided cognitive ability into multiple domains, shifting assessment away from a single composite measure and toward a more differentiated understanding of mental function.

Wechsler introduced the Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale in 1939, followed by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) in 1955.34 These tests separated verbal and performance tasks, allowing examiners to analyze patterns in reasoning, memory, processing speed, and spatial ability. The structure of the WAIS marked a significant departure from earlier systems that privileged a single score. Wechsler argued that intelligence reflected the global capacity of an individual to act purposefully, think rationally, and deal effectively with the environment. His scales operationalized this insight by generating multiple indices rather than compressing cognitive performance into one number.

As the WAIS and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) gained prominence, clinicians and researchers adopted increasingly sophisticated psychometric techniques.35 Standardization samples expanded, reliability and validity studies multiplied, and subtest structures were refined to capture a broader range of abilities. These developments allowed practitioners to distinguish among verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning, working memory, and processing speed. The Wechsler system thereby contributed to a more nuanced empirical picture of intelligence, aligning assessment practices with emerging theories in cognitive psychology.

Revisions of the Stanford-Binet test also reflected this movement toward multidimensional assessment.36 Modern iterations of the test incorporated hierarchical models of cognitive ability, expanded age ranges, and updated norms designed to reflect contemporary populations. By integrating research on developmental psychology and factor analysis, test designers recognized that intelligence is not static across the lifespan and cannot be reduced to a single pathway of reasoning. Contemporary versions of both the Stanford-Binet and the Wechsler scales are used not only to assess general ability but also to identify learning disabilities, developmental disorders, and areas requiring educational support.

Despite these advances, modern intelligence tests have continued to face scrutiny. Critics have pointed to cultural bias, socioeconomic disparities, and the influence of environmental factors on test performance.37 Research in developmental neuroscience and behavioral genetics has further complicated the picture by showing that cognitive ability emerges from the interaction of multiple biological and environmental influences. These findings challenge simplistic interpretations of test scores while reinforcing the need for careful, context-sensitive evaluation. Modern assessments therefore represent an ongoing dialogue between empirical method, ethical responsibility, and evolving scientific theory.

Controversies, Misuse, and Ethical Transformations

The expansion of intelligence testing in the early twentieth century coincided with growing interest in heredity, population management, and social efficiency. Many researchers interpreted test scores as indicators of innate mental capacity, often neglecting the influence of education, poverty, language, and culture.38 This assumption made intelligence testing vulnerable to ideological projects that sought scientific authority for social hierarchies. While the tests promised objective measurement, their interpretation frequently reflected the racial, economic, and political anxieties of the societies that used them. The belief in fixed, inherited intelligence became one of the most consequential misapplications of early psychometric science.

Eugenicists seized on intelligence testing as evidence that intellectual deficiency was widespread and biologically rooted. Figures in both the United States and Britain argued that low test scores justified compulsory sterilization, restrictive marriage laws, and the segregation of individuals labeled as “feebleminded.”39 Courts and legislatures incorporated test results into policy decisions, treating them as reliable indicators of hereditary worth. The 1927 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Buck v. Bell, which upheld compulsory sterilization, relied heavily on the authority of intelligence scores. These policies demonstrated how the perceived objectivity of numerical assessment could be appropriated for coercive and discriminatory ends, with consequences that extended far beyond the domain of psychological research.

Immigration policy also became entangled with intelligence testing. After World War I, psychologists such as Henry Goddard and others used Army Alpha and Beta test results to claim that recent immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe scored lower than earlier immigrant groups.40 These conclusions were drawn without considering language barriers, literacy, or the cultural assumptions embedded in test items. Nevertheless, they influenced public debate and provided support for the restrictive Immigration Act of 1924. The use of test results in this context illustrates how psychometrics could be misinterpreted to serve nativist and exclusionary policies, reinforcing racial and ethnic stereotypes through a veneer of scientific legitimacy.

As concerns mounted, researchers began to challenge the foundational assumptions of early intelligence testing. Scholars pointed out that test performance correlated strongly with schooling, socioeconomic background, and cultural exposure.41 Anthropologists, sociologists, and psychologists criticized the tendency to conflate test results with biological inheritance. Over time, these critiques undermined claims that intelligence was a single, fixed, inherited trait. They also encouraged a reconsideration of the social conditions under which tests were administered and interpreted. This growing skepticism created space for new models that emphasized environmental influences and the multifaceted nature of cognitive development.

Ethical reforms within psychology emerged in response to these critiques. Professional standards increasingly required examiners to consider cultural context, linguistic background, and educational opportunity when interpreting test results.42 Clinical and educational psychologists developed guidelines to prevent misuse, emphasizing that intelligence tests should be used to identify learning needs and support individuals rather than categorize them rigidly. Advances in cognitive psychology, developmental science, and neuroscience further demonstrated that cognitive ability is shaped by a dynamic interplay of biological and environmental factors. These developments helped shift the practice of intelligence testing away from hereditarian assumptions and toward a more contextual, person-centered approach.

Despite these improvements, debates about fairness, cultural bias, and the meaning of intelligence persist in contemporary scholarship. Researchers continue to examine how socioeconomic inequities affect test performance, how different cultural groups interpret test items, and whether a single construct can adequately represent diverse forms of human cognition.43 Modern psychometrics has made significant progress in reliability and validity, yet concerns remain about the uses to which test scores are put in educational placement, clinical diagnosis, and public policy. The ongoing controversy highlights the enduring tension between the desire to measure mental ability and the ethical responsibilities that accompany such measurement. Intelligence testing thus remains a domain where scientific method, social values, and political implications intersect in complex and often contentious ways.

Conclusion: Intelligence as a Moving Target

The long history of intelligence assessment demonstrates that societies have always sought ways to understand human ability, but the meanings and methods of measurement have changed dramatically over time. Ancient China evaluated competence through mastery of practical and moral skills cultivated within a rigorous educational tradition. Ancient Greece approached intelligence through philosophical analysis, focusing on the nature of reason rather than attempts at quantification. These early systems highlight the central point that conceptions of intelligence reflect broader cultural ideals about what it means to know, to reason, and to act wisely.44 Their approaches were embedded in moral formation, civic responsibility, and the pursuit of knowledge rather than numeric evaluation.

The emergence of scientific testing in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries marked a profound departure from these earlier traditions. Psychologists in Europe and the United States began to treat intelligence as a measurable entity, constructing tests that could classify individuals according to standardized criteria. This transition brought methodological rigor and the possibility of large-scale assessment, but it also introduced the risk of reducing complex human qualities to a single dimension. The widespread adoption of the IQ framework illustrated both the power and the limitations of quantification.45 Intellectual diversity, shaped by varied cultural, environmental, and developmental influences, was often compressed into a single numerical value.

As psychometric methods evolved, researchers recognized the need for more differentiated models of cognitive functioning. The development of tests like the Stanford-Binet and the Wechsler scales reflected this shift, incorporating multiple indices and acknowledging that intelligence is a composite of distinct abilities. Advances in cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and educational research further underscored that intellectual development is dynamic and influenced by an interplay of biological and environmental factors. Modern assessment practices therefore reflect a growing awareness that intelligence cannot be understood fully through a singular measure, even when that measure is psychometrically sophisticated.46

Despite substantial progress, debates about the nature and measurement of intelligence remain ongoing. Questions about fairness, cultural bias, and the ethical use of testing continue to shape both research and public policy. Contemporary scholarship increasingly emphasizes the variability of human cognition and the need for context-sensitive approaches that avoid the determinism of early psychometric theories.47 This long historical trajectory, from philosophical inquiry to modern standardized testing, demonstrates that intelligence is best understood not as a fixed or isolated attribute but as a complex, evolving concept shaped by cultural values, scientific methods, and ethical commitments.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Benjamin A. Elman, A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 1–12; Lloyd P. Gerson, Aristotle and Other Platonists (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005), 103–110.

- Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981), 62–79.

- John Carson, The Measure of Merit: Talents, Intelligence, and Inequality in the French and American Republics, 1750–1940 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 161–175.

- Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 56–85.

- Nancy Stepan, The Idea of Race in Science: Great Britain, 1800–1960 (London: Macmillan, 1982), 110–118.

- James R. Flynn, What Is Intelligence? Beyond the Flynn Effect (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 1–14.

- Elman, A Cultural History of Civil Examinations, 20–26.

- Elman, A Cultural History of Civil Examinations, 98–112.

- Liu Xie, The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons, trans. Vincent Yu-chung Shih (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2015), 45–48.

- Mark Lewis, The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 184–190.

- Plato, Republic, trans. C. D. C. Reeve (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004), 509d–511e; Plato, Phaedrus, trans. Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1995), 247c–249d.

- Julia Annas, Platonic Ethics, Old and New (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 35–44.

- Gerson, Aristotle and Other Platonists, 115–123.

- Terence Irwin, Classical Thought (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 82–94.

- Michael Bulmer, Francis Galton: Pioneer of Heredity and Biometry (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 67–82.

- Francis Galton, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development (London: Macmillan, 1883), 191–224.

- Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, 96–113.

- Theodore M. Porter, The Rise of Statistical Thinking, 1820–1900 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 241–252.

- Carson, The Measure of Merit, 151–160.

- Alfred Binet, Modern Ideas About Children, trans. Sidney Arthurs (New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1975), 20–28.

- Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon, “Méthodes nouvelles pour le diagnostic du niveau intellectuel des anormaux,” L’Année Psychologique 12 (1905): 191–244.

- Laurence D. Smith, Behaviorism and Logical Positivism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986), 114–118.

- Binet, Modern Ideas About Children, 45–52.

- H. H. Spitz, Nonconscious Movements: From Mysteries to Science (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1997), 132–138.

- William Stern, The Psychological Methods of Testing Intelligence, trans. Guy Montrose Whipple (Baltimore: Warwick & York, 1914), 40–48.

- Lewis M. Terman, The Measurement of Intelligence (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1916), 79–102.

- Carson, The Measure of Merit, 197–210.

- Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, 148–158.

- Robert M. Yerkes, ed., Psychological Examining in the United States Army (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921), 1–25.

- Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, 192–208.

- Carson, The Measure of Merit, 230–242.

- Stepan, The Idea of Race in Science, 142–150.

- David Wechsler, The Measurement of Adult Intelligence, 3rd ed. (Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1944), vii–xii.

- David Wechsler, Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (New York: Psychological Corporation, 1955).

- Alan S. Kaufman, Intelligent Testing with the WISC-R (New York: Wiley, 1979), 11–22.

- Gale H. Roid, Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition (SB5) (Itasca: Riverside Publishing, 2003).

- Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, 243–270.

- Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, 156–170.

- Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics, 66–89.

- John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1955), 266–276.

- Carl N. Degler, In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 211–223.

- American Psychological Association, Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (Washington, DC: APA, 1985), 14–24.

- Richard E. Nisbett et al., “Intelligence: New Findings and Theoretical Developments,” American Psychologist 67, no. 2 (2012): 130–159.

- Gerson, Aristotle and Other Platonists, 103–110.

- Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, 147–158.

- Alan S. Kaufman, Intelligent Testing with the WISC-R (New York: Wiley, 1979), 11–22.

- Nisbett et al., “Intelligence: New Findings and Theoretical Developments,” 130–159.

Bibliography

- American Psychological Association. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1985.

- Annas, Julia. Platonic Ethics, Old and New. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Binet, Alfred. Modern Ideas About Children. Translated by Sidney Arthurs. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1975.

- Binet, Alfred, and Théodore Simon. “Méthodes nouvelles pour le diagnostic du niveau intellectuel des anormaux.” L’Année Psychologique 12 (1905): 191–244.

- Bulmer, Michael. Francis Galton: Pioneer of Heredity and Biometry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

- Carson, John. The Measure of Merit: Talents, Intelligence, and Inequality in the French and American Republics, 1750–1940. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Degler, Carl N. In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Elman, Benjamin A. A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Flynn, James R. What Is Intelligence? Beyond the Flynn Effect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Galton, Francis. Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. London: Macmillan, 1883.

- Gerson, Lloyd P. Aristotle and Other Platonists. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005.

- Gould, Stephen Jay. The Mismeasure of Man. New York: W. W. Norton, 1981.

- Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1955.

- Irwin, Terence. Classical Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Kaufman, Alan S. Intelligent Testing with the WISC-R. New York: Wiley, 1979.

- Kevles, Daniel J. In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Lewis, Mark. The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Liu Xie. The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons. Translated by Vincent Yu-chung Shih. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2015.

- Nisbett, Richard E., Joshua Aronson, Clancy Blair, William Dickens, James Flynn, Diane F. Halpern, and Eric Turkheimer. “Intelligence: New Findings and Theoretical Developments.” American Psychologist 67, no. 2 (2012): 130–159.

- Porter, Theodore M. The Rise of Statistical Thinking, 1820–1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Roid, Gale H. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition (SB5). Itasca: Riverside Publishing, 2003.

- Smith, Laurence D. Behaviorism and Logical Positivism. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986.

- Spitz, H. H. Nonconscious Movements: From Mysteries to Science. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1997.

- Stepan, Nancy. The Idea of Race in Science: Great Britain, 1800–1960. London: Macmillan, 1982.

- Stern, William. The Psychological Methods of Testing Intelligence. Translated by Guy Montrose Whipple. Baltimore: Warwick & York, 1914.

- Terman, Lewis M. The Measurement of Intelligence. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

- Wechsler, David. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. New York: Psychological Corporation, 1955.

- Wechsler, David. The Measurement of Adult Intelligence. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1944.

- Yerkes, Robert M., ed. Psychological Examining in the United States Army. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.