The conversion of Lithuania illustrates how religious change in the medieval world could emerge from political calculation rather than theological persuasion.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Lithuania at the Edge of Christian Europe

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania stood apart in late medieval Europe. While the rest of the continent had long been drawn into the institutions and cultural rhythms of Latin Christendom, Lithuania remained an officially pagan polity well into the fourteenth century. Its persistence was not an accident of geography or cultural inertia. Instead, it reflected the political strategies of a ruling elite who governed a vast and multiethnic realm stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Their religious position was intertwined with questions of sovereignty, identity, and survival, particularly as crusading powers in the region sought to force the issue of conversion through military campaigns.1

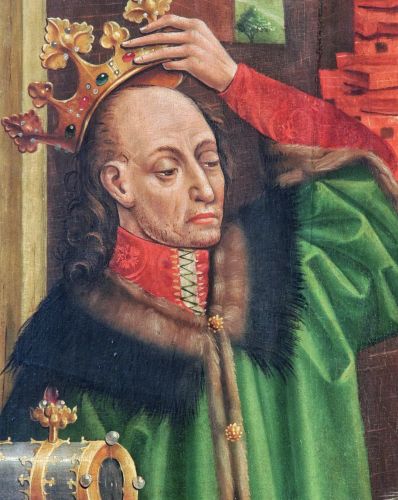

This distinctive position created a tension that shaped Lithuanian diplomacy. By the time Jogaila emerged as Grand Duke in the 1370s, the pressures were acute. The Teutonic Order continued to justify its wars as holy efforts to Christianize Lithuania, and both Poland and Muscovy sought influence over its future. Jogaila’s decision to convert to Catholicism in 1386 and to marry Queen Jadwiga of Poland was therefore deeply political. The arrangement, formalized through the Union of Krewo, offered both the end of crusading aggression and a new dynastic alignment that shifted the balance of power across Eastern Europe.2

The baptism of Jogaila and the subsequent Christianization of Lithuania in 1387 altered the structure and orientation of the state. New legal frameworks, administrative reforms, and ecclesiastical foundations created an institutional landscape that linked Lithuania more directly to Western Christendom. Yet conversion at the level of policy did not eliminate pre-Christian ritual culture. Rural communities continued long-standing practices, sometimes discreetly and sometimes in blended forms that mirrored broader patterns of syncretism in medieval Europe.3

These dynamics establish the historical problem examined in this essay. Lithuania’s late conversion was not merely a religious shift but a transformation of political order, cultural meaning, and international identity. The following sections trace this process from pre-Christian statecraft through dynastic negotiations, administrative reforms, regional conflicts, and the lived realities of conversion on the ground. The aim is to illuminate the specificity of Lithuania’s experience and to understand how a pagan polity became a Christian kingdom without erasing its deeper cultural foundations.4

Lithuania Before 1387: Pagan Statehood, Society, and Political Structures

Lithuania’s endurance as a pagan state was rooted in a political order that drew strength from its indigenous religious framework. The ruling dynasty relied on a network of regional leaders whose authority was tied to ritual obligations and funerary traditions that marked status within the community. Paganism served as the ideological glue of a polity that had expanded rapidly, incorporating Baltic, Ruthenian, and other populations whose loyalties depended more on personal alliances than on codified institutions.5 This structure proved resilient in the face of Christian neighbors and created a foundation from which Lithuanian rulers could negotiate or resist external pressures without sacrificing their authority.

The religious landscape of pre-Christian Lithuania was characterized by a pantheon whose attributes are partially recoverable from later chroniclers and archaeological remains. Deities such as Perkūnas and Žemyna appear in medieval descriptions, although the reliability of these texts requires caution due to the polemical agendas of their authors. Jan Długosz, writing in the fifteenth century, offers the fullest narrative, but his interpretation often reflects classical analogies rather than direct observation.6 Archaeological material, including cremation burials, ritual offerings, and sacred groves identified through excavations by the Lithuanian Institute of History, provides firmer evidence for the religious world inhabited by ordinary people.7 These practices framed both social identity and governance, giving Lithuanian leaders cultural legitimacy that a premature conversion risked undermining.

Political considerations reinforced the desire to maintain traditional beliefs. The Grand Duchy’s rise in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries depended on its ability to balance regional powers while absorbing new territories. Pagan identity allowed Lithuanian rulers to position themselves independently between Latin Christendom and the Orthodox world. The Teutonic Order’s ongoing crusade created a military threat, but it also offered diplomatic leverage. Lithuanian dukes could negotiate truces or alliances on their own terms precisely because they remained the target of missionary claims.8 The internal hierarchy of the realm, built on kin networks and personal loyalty, depended on the perception that the ruling dynasty embodied the sacred order of the land.

These dynamics complicate later narratives that portray Lithuania’s conversion as a delayed but inevitable acceptance of European norms. Paganism was not an atavistic residue but an active component of state formation, diplomacy, and social organization. Its eventual abandonment required more than theological persuasion. It demanded a structural realignment of authority, ritual practice, and political identity that could only occur when the benefits of dynastic union outweighed the risks to internal cohesion.9

Dynastic Politics and the Union of Krewo: Why Jogaila Converted

Jogaila’s conversion must be understood within the volatile political environment of the late fourteenth century. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania faced simultaneous pressures from the Teutonic Order, the rising power of Moscow, and internal rivalries among members of the Gediminid dynasty. These forces created a diplomatic landscape in which neutrality was becoming increasingly difficult to maintain. The realm’s pagan status, once a tool for balancing between Christian neighbors, now threatened its stability by inviting crusading aggression and complicating relations with nearby Christian powers. Jogaila’s search for a durable political solution emerged from these shifting constraints.10

The Union of Krewo in 1385 provided that solution. Through the agreement, Jogaila pledged to marry Queen Jadwiga of Poland, adopt Catholic Christianity, and bring his realm into communion with Rome. In return, he would assume the Polish throne and establish a dynastic union that reshaped power across Eastern Europe. The text of the union, preserved in diplomatic collections, reveals clear political aims rather than theological motivations.11 Jogaila sought not only to end decades of conflict with the Teutonic Order but also to prevent rival Lithuanian leaders, including his cousin Vytautas, from forming their own alliances with Christian powers. Baptism offered a way to consolidate authority at home while redirecting Lithuania’s position on the international stage.

Jogaila’s alternatives underscore the strategic nature of his choice. Negotiations with Moscow involved the possibility of conversion to Orthodoxy, an option that would have aligned Lithuania with the emerging Russian state. This prospect was unattractive to many Lithuanian elites, who saw Moscow as both a political competitor and a threat to their autonomy.12 Aligning with the Teutonic Order, another potential avenue, would have required Lithuanian subordination to a military monastic power that had been waging campaigns against the duchy for decades. The Polish offer, by contrast, provided a path to kingship and a more advantageous alliance.

The role of Queen Jadwiga and the Polish nobility further shaped the union’s formation. Jadwiga, crowned as “king” of Poland due to her sovereign status, required a consort capable of reinforcing her legitimacy without undermining the authority of the Polish crown. Jogaila’s acceptance of Christianization was a political condition embedded in the marriage negotiations, but it also aligned with the ambitions of the Polish elite, who sought to strengthen their position against both Hungary and the Teutonic Order.13 The resulting dynastic arrangement represented a convergence of interests that made religious transformation a component of broader statecraft.

The final shape of the union laid the groundwork for the Jagiellonian dynasty and initiated far-reaching changes in governance, diplomacy, and territorial strategy. Jogaila’s conversion ended the ideological justification for crusade and opened pathways to Western alliances. At the same time, it set into motion internal reforms that altered the relationship between Lithuanian rulers and their subjects.14 The decision to convert was thus not a simple matter of religious adoption but a calculated response to regional geopolitics that transformed both Lithuania and Poland for centuries.

The Baptism of 1387 and the Reshaping of State Institutions

The Christianization of Lithuania in 1387 marked a turning point in the political and administrative life of the Grand Duchy. Jogaila issued a series of charters establishing the framework for the new Catholic order in the region, beginning with the creation of parishes and the confirmation of privileges to Lithuanian nobles who accepted baptism. These documents reshaped the relationship between ruler and elite, tying political loyalty to participation in a new religious structure. They also reflected Jogaila’s efforts to secure support within a realm marked by longstanding regional rivalries.15 The language of these charters shows a deliberate attempt to integrate Lithuania into the legal traditions of Latin Christendom.

The founding of the bishopric of Vilnius played an essential role in this institutional reorientation. Papal correspondence from 1387 and 1388 demonstrates how carefully the creation of the diocese was negotiated, with attention to its territorial jurisdiction and the authority of the new bishop, Andrzej Jastrzębiec.16 The establishment of episcopal oversight introduced Latin administrative culture into the duchy, including the use of written records, ecclesiastical courts, and standardized ritual practices. This infrastructure strengthened ties between Lithuania and Rome and provided Jogaila with tools to extend central oversight into regions where the authority of the grand ducal court had long been mediated through kin networks.

These developments also had legal consequences. The new privileges granted to baptized nobles altered patterns of landholding and jurisdiction, offering legal protections modeled on Western norms. Rights granted in the 1387 charters included hereditary land tenure and exemptions from certain obligations, creating incentives for elite participation in the Christian order.17 While these reforms strengthened the social position of the Lithuanian nobility, they also encouraged a gradual shift from customary law toward written statutes that reflected broader European trends. This transition did not immediately displace older forms of adjudication but created a layered legal culture in which Latin and indigenous practices coexisted.

The administrative changes initiated by Christianization extended beyond the nobility. Clergy trained in Polish and Western institutions introduced new forms of record keeping and literacy that slowly filtered into secular governance. The adoption of Latin, both as a liturgical language and as a medium for legal documentation, linked Lithuania to the diplomatic practices of neighboring kingdoms.18 These connections allowed Lithuanian rulers to participate more fully in the international communication networks that defined late medieval statecraft. The circulation of letters, treaties, and ecclesiastical directives helped normalize the duchy’s position within European political culture.

Despite these transformations, Christianization did not erase existing structures of authority. Local leaders continued to wield influence through customary practices, and elements of pre-Christian ritual persisted in communities where ecclesiastical institutions remained thin. The integration of Western forms of governance proceeded unevenly, shaped by regional diversity and the pace of institutional development. Lithuanian rulers worked within these constraints, using the Christian framework to extend their reach while accommodating local expectations.19 The resulting system was neither a complete imposition of foreign models nor a simple continuation of older traditions, but a hybrid administrative order that reflected the complexities of late fourteenth-century Lithuania.

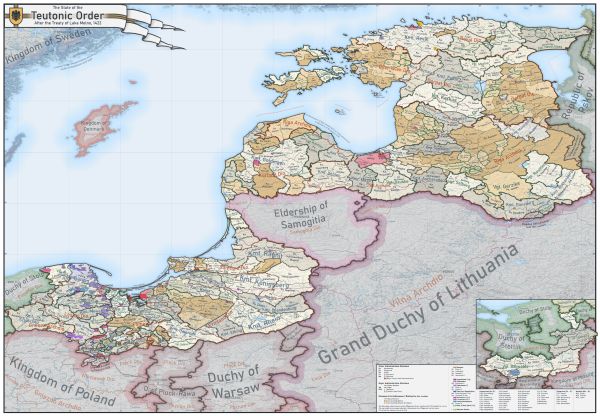

The Samogitian Question: A Second Conversion (1413–1417)

Samogitia occupied a strategic position that made its conversion a distinct and prolonged process within the broader Christianization of Lithuania. Unlike eastern and central Lithuanian lands, Samogitia lay directly between the Teutonic Order’s territories in Prussia and Livonia, making it the focal point of repeated military campaigns. The region changed hands multiple times during the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and its inhabitants experienced sustained pressure from crusading forces claiming the right to impose baptism. The political contest over Samogitia therefore shaped how and when Christianization could occur, since neither the Order nor the Lithuanian rulers could implement lasting reforms until territorial control was firmly established.20

The Treaty of Salynas in 1398 and the Treaty of Raciąż in 1404 temporarily granted Samogitia to the Order, but resistance within the region and conflicts among regional powers undermined these agreements. The decisive shift came only after the Polish-Lithuanian victory at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, which dismantled the military strength of the Teutonic Order and opened a path toward durable Lithuanian authority. Vytautas the Great played a central role in this transition. His involvement in the region combined military intervention with negotiated settlements that culminated in renewed efforts to establish parishes and promote formal baptism.21 The political stabilization achieved after Grunwald allowed Vytautas to advance a more systematic Christianization program without the constant threat of external interference.

The Council of Constance, held between 1414 and 1418, also influenced Samogitia’s conversion. Lithuanian delegates used the council as a forum to challenge the Teutonic Order’s longstanding claims that Lithuania and Samogitia had resisted Christianity in bad faith. Official records from the council preserve testimonies and legal arguments that refuted the Order’s allegations and affirmed the legitimacy of Lithuanian efforts to organize ecclesiastical structures.22 This diplomatic strategy weakened the Order’s ideological justification for intervention, allowing Vytautas to proceed with the establishment of new churches and to appoint clergy who were not subject to Order oversight. The council thus played a part in legitimizing Samogitia’s integration into the Catholic sphere on Lithuanian rather than foreign terms.

The final consolidation occurred after the Treaty of Melno in 1422, which permanently settled the border disputes between Lithuania and the Teutonic Order. Only then could the ecclesiastical framework in Samogitia be completed without disruption. Baptisms, parish organization, and the creation of local administrative structures proceeded unevenly but steadily, reflecting the complexities of introducing a new religious system into a territory shaped by decades of conflict.23 Samogitia’s conversion therefore stands not simply as a chronological extension of the 1387 baptism but as evidence that Christianization in Lithuania unfolded through regionally specific negotiations shaped by war, diplomacy, and the competing agendas of neighboring powers.

Christianization on the Ground: Rural Religion, Persistence, and Syncretism

The Christianization of Lithuania unfolded unevenly across the social landscape, and nowhere was this more apparent than in rural regions. While the baptism of 1387 established an official framework for the acceptance of Catholicism, the lived experience of conversion varied significantly from community to community. Many villages lacked immediate access to clergy, and the establishment of parishes proceeded more slowly in remote areas. Ecclesiastical visitations conducted in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries reveal concerns about the resilience of older rites, suggesting that conversion at the local level was an ongoing process rather than a single event.24 Differences in local leadership, population density, and proximity to administrative centers all shaped the degree to which Christian norms took root.

Traditional ritual practices remained embedded in communal life even as the institutional presence of the Church expanded. Reports from the bishopric of Vilnius, preserved in later compilations of diocesan records, describe continued offerings at sacred groves and the persistence of seasonal rites that were only partially reinterpreted within a Christian context.25 These activities reflected the importance of long-standing ritual sites that had served as markers of communal identity. Many of these places were linked to specific kin groups or local leaders whose authority was reinforced through their association with traditional religious observances. The endurance of these practices highlights how the rhythms of rural life shaped the reception of Christian teachings.

Syncretism emerged as one way in which rural communities navigated the transition to the new religious order. Elements of pre-Christian ritual were often incorporated into practices surrounding major life events such as births, weddings, and funerals. Archaeological evidence from burial sites in the fifteenth century shows variations in grave goods and burial orientation that suggest blended customs.26 While these remains cannot be equated directly with specific theological beliefs, they illustrate how communities adapted inherited forms within the new Christian framework. Local clergy, themselves often recently trained or unfamiliar with regional traditions, encountered a religious environment in which older and newer elements coexisted.

The landscape itself played a role in sustaining pre-Christian practices. Sacred groves, springs, and stones identified through archaeological surveys continued to attract veneration even after parish structures had been established. In some cases, Christian symbols were placed at these locations, either by clergy attempting to reframe their significance or by villagers who interpreted the new symbols within older cosmological patterns.27 The interplay between place and ritual demonstrates how deeply embedded certain traditions were, making the transformation of religious culture a gradual process shaped by local memory and geography.

Efforts by Church authorities to standardize worship and eliminate non-Christian customs met with mixed success. Episcopal statutes issued in the fifteenth century targeted specific practices such as divination, ritual feasting, and forms of healing that drew on long-standing local knowledge.28 These prohibitions indicate not only the persistence of such customs but also the adaptive strategies communities employed to reconcile them with Christian expectations. In many cases, the boundaries between acceptable local tradition and prohibited ritual were fluid, negotiated through interactions among clergy, village leaders, and households.

By the later fifteenth century, the cumulative effect of parish formation, clerical engagement, and political consolidation had brought most rural communities into closer alignment with Christian norms. Even so, traces of earlier practices endured, reflected in seasonal festivals, household rituals, and community gatherings documented by later ethnographic research.29 These survivals should not be interpreted as static remnants of an untouched pagan past but as part of a dynamic process through which Lithuanian communities integrated new religious frameworks into their existing cultural landscapes. The result was a form of Christianity shaped both by ecclesiastical authority and by the deep-rooted traditions that had long structured rural life.

Lithuania and the Politics of European Christendom After Conversion

Lithuania’s entry into the Christian world reconfigured its diplomatic position across Europe. Once regarded as an ideological target for crusading efforts, the duchy now appeared as a legitimate participant in the political and ecclesiastical networks that shaped regional affairs. Papal correspondence in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries reflects this shift, as the curia began to treat Lithuania less as a battleground for missionary intervention and more as a Christian polity whose rulers required guidance and recognition.30 This change allowed Lithuanian leaders to engage with neighboring powers on terms grounded in shared religious norms rather than in the asymmetrical logic of conversion campaigns.

The transformation also affected relations with the Teutonic Order. With Jogaila’s baptism and the establishment of Christian institutions in Lithuania, the ideological basis for the Order’s crusading mission diminished sharply. The Order continued to question the sincerity of Lithuanian conversion, a position evident in its diplomatic arguments at the Council of Constance, but these claims increasingly lacked credibility once parishes, episcopal oversight, and administrative reforms were in place.31 The loss of moral authority undermined the Order’s ability to attract support from Western European nobles, contributing to its decline after the defeat at Grunwald in 1410. Lithuania’s new standing in Christendom thus eroded one of its most persistent adversaries.

Within the region, conversion facilitated the consolidation of the Jagiellonian political order. The shared Catholic framework between Poland and Lithuania strengthened the union by providing a common religious and cultural vocabulary for elite interaction. Ecclesiastical institutions became channels for political communication, as bishops, monastic houses, and clerical envoys helped coordinate diplomatic activities across the two realms.32 These developments contributed to the emergence of a more integrated political culture, in which Lithuanian elites participated alongside their Polish counterparts in shaping the policies of the growing Jagiellonian state. The spread of Latin literacy and clerical education further supported this integration.

Lithuania’s alignment with Western Christendom also affected its relationships to Orthodox principalities. Before conversion, Lithuania had governed many Ruthenian territories with considerable flexibility, allowing Orthodox communities to maintain their traditions under grand ducal rule. After 1387, the duchy increasingly positioned itself as a mediator between Western and Eastern Christian spheres, a role visible in treaties, dynastic marriages, and administrative practices.33 This balancing act enhanced Lithuania’s diplomatic significance, enabling its rulers to navigate the complex politics of Eastern Europe while maintaining influence among both Latin and Orthodox elites. The religious diversity of the duchy became an asset rather than an obstacle.

By the mid-fifteenth century, Lithuania had fully entered the institutional landscape of European Christendom. Its rulers participated in diplomatic congresses, issued charters modeled on Western precedents, and engaged with monastic and ecclesiastical networks that extended across the continent.34 The process was neither instantaneous nor uniform, but the gradual accumulation of reforms, alliances, and shared religious frameworks reshaped Lithuania’s long-term trajectory. Christianization allowed the duchy to move beyond the defensive posture that had characterized its earlier history and to emerge as a central actor in the political and cultural life of Eastern Europe.

Conclusion: Statecraft, Faith, and the Ambivalence of Medieval Conversion

The conversion of Lithuania illustrates how religious change in the medieval world could emerge from political calculation rather than theological persuasion. Jogaila’s baptism and the reforms that followed were responses to pressures generated by regional conflicts, dynastic rivalries, and the expanding reach of Christian institutions. These decisions reshaped the grand ducal court, reordered elite alliances, and redirected Lithuania’s place within European diplomacy.35 The significance of the 1387 conversion lies not only in its religious dimension but also in its capacity to resolve geopolitical dilemmas that had troubled Lithuanian rulers for decades.

At the same time, Christianization did not result in the immediate disappearance of earlier cultural forms. Rural communities continued to observe long-standing rites, interpret sacred landscapes through inherited frameworks, and adapt new Christian practices in ways that preserved elements of local identity. Archaeological and documentary evidence reveals that these traditions persisted well into the fifteenth century, often in blended forms that reflected the complexities of everyday religious life.36 The endurance of these practices demonstrates how conversion unfolded as a negotiation between ecclesiastical authority and the cultural memory embedded within village life.

The political consequences of conversion extended far beyond Lithuania’s internal structures. By entering Christian diplomatic networks, the duchy gained tools to contest the ideological claims of the Teutonic Order and to participate in broader European affairs. The emergence of the Jagiellonian dynasty strengthened ties with Poland and contributed to the development of a political order that bridged Latin and Orthodox Christian spheres.37 Through these transformations, Lithuania became an intermediary between cultural worlds, shaping the balance of power in Eastern Europe for generations.

Taken together, these developments reveal that Lithuania’s Christianization was a layered and ambivalent process. It involved the strategic adoption of new institutions, the gradual reshaping of local practices, and the creation of a hybrid cultural landscape that incorporated elements of both older and newer traditions. The endurance of pre-Christian rituals alongside the consolidation of Catholic governance underscores the adaptability of Lithuanian society as it navigated the challenges of political survival and cultural continuity.38 In this convergence of statecraft and religious transformation, Lithuania’s experience stands as a distinctive example of how medieval polities encountered, negotiated, and ultimately redefined the boundaries of Christian Europe.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Peter of Dusburg, Chronicon terrae Prussiae, in William Urban, The Prussian Crusade (Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, 1975), 45–47.

- Robert Frost, The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, Volume I: The Making of the Polish-Lithuanian Union, 1385–1569 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 46–58.

- S. C. Rowell, Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire Within East-Central Europe, 1295–1345 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 213–221.

- S. C. Rowell, Lithuania and the Christian World, 1200–1600 (Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2007), 91–112.

- Henryk Łowmiański, Studia nad dziejami Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego (Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1983), 41–56.

- Jan Długosz, Annales seu cronicae incliti Regni Poloniae, ed. Krzysztof Baczkowski (Warsaw: PWN, 1964–2005), vol. 12, 88–95.

- Vykintas Vaitkevičius, Studies into the Balts’ Sacred Places (Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2004), 23–44.

- Eric Christiansen, The Northern Crusades (London: Penguin, 1980), 162–171.

- Rowell, Lithuania and the Christian World, 54–68.

- Frost, The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, Volume I, 33–42.

- Codex diplomaticus Regni Poloniae et Magni Ducatus Lituaniae, ed. Eugeniusz Kucharski (Vilnius: Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, 1941), 112–115.

- John Fennell, The Crisis of Medieval Russia, 1200–1304 (London: Longman, 1983), 198–204.

- Norman Davies, God’s Playground: A History of Poland, Volume I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 78–84.

- Rowell, Lithuania Ascending, 245–257.

- Jogaila’s Charters for Lithuania, in Codex diplomaticus Lithuaniae, ed. Eugeniusz Kucharski (Vilnius: Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, 1941), 142–151.

- Bullarium Poloniae, ed. Heinrich Finke (Rome: Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis, 1907), 312–315.

- Frost, The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, Volume I, 72–79.

- Christiansen, The Northern Crusades, 214–220.

- Rimvydas Petrauskas, Between Rome and Byzantium: The Golden Age of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s Political Culture (Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2020), 65–73.

- William Urban, The Samogitian Crusade (Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, 1989), 58–66.

- Rowell, Lithuania Ascending, 268–275.

- Acta Concilii Constantiensis, ed. Heinrich Finke (Münster: Aschendorff, 1896), vol. 2, 413–421.

- Christiansen, The Northern Crusades, 214–220.

- Raimonda Ragauskienė, Visitations of the Diocese of Vilnius: Sources for the History of Rural Religion (Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2008), 17–26.

- Darius Baronas, The Formation of Catholic Communities in Lithuania (Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2013), 51–63.

- Gintautas Zabiela, “Burial Traditions in Northeast Lithuania.” In A Hundred Years of Archaeological Discoveries in Lithuania. Vilnius: Lietuvos Archeologijos Draugija, (2016): 326-337.

- Vaitkevičius, Studies into the Balts’ Sacred Places, 68–84.

- Statuta ecclesiastica dioecesis Vilnensis, ed. Mečislovas Jučas (Vilnius: Mintis, 1987), 44–51.

- Daiva Vaitkevičienė, The Rose and Blood: Images of Fire in Baltic Mythology, Cosmos Vol. 17, Iss. 1 (2003), 21-42.

- Bullarium Poloniae, ed. Heinrich Finke (Rome: Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis, 1907), 318–327.

- Acta Concilii Constantiensis, vol. 3, 224–233.

- Frost, The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, Volume I, 143–157.

- David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth-Century Wilno (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013), 29–41.

- Christiansen, The Northern Crusades, 214–220.

- Frost, The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, Volume I, 189–201.

- Zabiela, Archaeology of Lithuania, 147–156.

- Christiansen, The Northern Crusades, 214–220.

- Darius Baronas and S.C. Rowell, The Conversion of Lithuania: From Pagan Barbarians to Late Medieval Christians (Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2015), 119–130.

Bibliography

- Baronas, Darius and S.C. Rowell. The Conversion of Lithuania: From Pagan Barbarians to Late Medieval Christians. Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2015.

- Christiansen, Eric. The Northern Crusades. London: Penguin, 1980.

- Davies, Norman. God’s Playground: A History of Poland, Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Długosz, Jan. Annales seu cronicae incliti Regni Poloniae. Edited by Krzysztof Baczkowski. Vol. 12. Warsaw: PWN, 1964–2005.

- Fennell, John. The Crisis of Medieval Russia, 1200–1304. London: Longman, 1983.

- Finke, Heinrich, ed. Acta Concilii Constantiensis. Vol. 2 and Vol. 3. Münster: Aschendorff, 1896.

- —-, ed. Bullarium Poloniae. Rome: Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis, 1907.

- Frick, David. Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth-Century Wilno. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013.

- Frost, Robert. The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, Volume I: The Making of the Polish-Lithuanian Union, 1385–1569. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Jučas, Mečislovas, ed. Statuta ecclesiastica dioecesis Vilnensis. Vilnius: Mintis, 1987.

- Kucharski, Eugeniusz, ed. Codex diplomaticus Regni Poloniae et Magni Ducatus Lituaniae. Vilnius: Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, 1941.

- Łowmiański, Henryk. Studia nad dziejami Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1983.

- Petrauskas, Rimvydas. Between Rome and Byzantium: The Golden Age of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s Political Culture. Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2020.

- Ragauskienė, Raimonda. Visitations of the Diocese of Vilnius: Sources for the History of Rural Religion. Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2008.

- Rowell, S.C. Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire Within East-Central Europe, 1295–1345. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Urban, William. The Prussian Crusade. Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, 1975.

- —-. The Samogitian Crusade. Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, 1989.

- Vaitkevičienė, Daiva. The Rose and Blood: Images of Fire in Baltic Mythology. Cosmos Vol. 17, Iss. 1 (2003), 21-42.

- Vaitkevičius, Vykintas. Studies into the Balts’ Sacred Places. Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2004.

- Zabiela, Gintautas. “Burial Traditions in Northeast Lithuania.” In A Hundred Years of Archaeological Discoveries in Lithuania. Vilnius: Lietuvos Archeologijos Draugija, 2016.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.28.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.