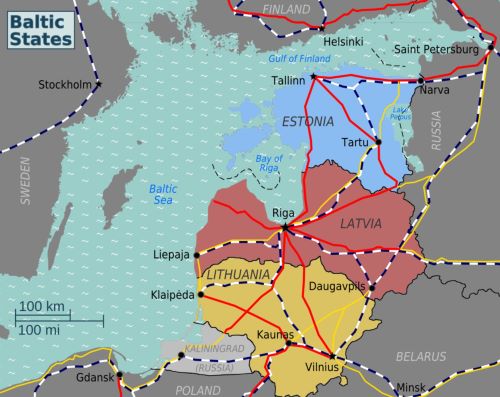

The term “Baltic states” refers to countries by the Baltic Sea that had gained independence from the Russian Empire.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The term Baltic stems from the name of the Baltic Sea – a hydronym dating back to at least 3rd century B.C. (when Erastothenes mentioned Baltia in an Ancient Greek text) and possibly earlier.[3] Although there are several theories about its origin, most ultimately trace it to the Indo-European root *bhel[4] meaning ‘white, fair’. This meaning is retained in modern Baltic languages, where baltas in Lithuanian and balts in Latvian mean ‘white’.[5] However, the modern names of the region and the sea that originate from this root, were not used in either of the two languages prior to the 19th century.[6]

Since the Middle Ages, the Baltic Sea has appeared on maps in Germanic languages as the equivalent of ‘East Sea’: German: Ostsee, Danish: Østersøen, Dutch: Oostzee, Swedish: Östersjön, etc. Indeed, the Baltic Sea lies mostly to the east of Germany, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The term was also used historically to refer to Baltic Dominions of the Swedish Empire (Swedish: Östersjöprovinserna) and, subsequently, the Baltic governorates of the Russian Empire (Russian: Остзейские губернии, romanized: Ostzejskie gubernii).[6]

Terms related to modern name Baltic appear in ancient texts, but had fallen into disuse until reappearing as the adjective Baltisch in German, from which it was adopted in other languages.[7] During the 19th century, Baltic started to supersede Ostsee as the name for the region. Officially, its Russian equivalent Прибалтийский (Pribaltiyskiy) was first used in 1859.[6] This change was a result of the Baltic German elite adopting terms derived from Baltisch to refer to themselves.[7][8]

The term Baltic countries (or lands, or states) was, until the early 20th century, used in the context of countries neighbouring the Baltic Sea: Sweden and Denmark, sometimes also Germany and the Russian Empire. With the advent of Foreningen Norden (the Nordic Associations), the term was no longer used for Sweden and Denmark.[9][10] After World War I, the new sovereign states that emerged on the east coast of the Baltic Sea – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Finland – became known as the Baltic states.[7]

After the First World War the term “Baltic states” came to refer to countries by the Baltic Sea that had gained independence from the Russian Empire. The term includes Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and originally also included Finland, which later became grouped among the Nordic countries.[11]

The areas of the Baltic states have seen different regional and imperial affiliations during their existence. They were first included under the same political entity when the Russian Empire expanded in the 18th century. The territories of Estonia and Latvia were ceded by Sweden, and incorporated into the Russian Empire at the end of the Great Northern War in 1721, while most of the territory of what is now Lithuania came under the Russian rule after the Third Partition of Poland in 1795. Large parts of the Baltic countries were controlled by the Russian Empire until the final stages of World War I in 1918, when Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania gained their sovereignty. The three countries were independent until the outbreak of World War II. In 1940, all three countries were invaded, occupied and annexed by the Stalinist Soviet Union. In 1941 followed the invasion and occupation of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia by Nazi Germany, before the Red Army reinvaded in 1944–1945 and the Soviet Union was able to regain control over the three countries until 1991. Soviet rule ended in the Baltic countries in 1989–1991 as the newly elected parliaments of the three nations declared the Soviet occupation illegal, culminating with the full restoration of the independence of the three countries in August 1991.

The First Period of Independence, 1918–1940

As World War I came to a close, Lithuania declared independence and Latvia formed a provisional government. Estonia had already obtained autonomy from tsarist Russia in 1917, and declared independence in February 1918, but was subsequently occupied by the German Empire until November 1918. Estonia fought a successful war of independence against Soviet Russia in 1918-20. Latvia and Lithuanian followed a similar process, until the completion of the Latvian War of Independence and Lithuanian Wars of Independence in 1920.

During the interwar period these countries were sometimes referred to as limitrophe states between the two World Wars, from the French, indicating their collectively forming a rim along Bolshevik Russia’s, later the Soviet Union’s, western border. They were also part of what Georges Clemenceau considered a strategic cordon sanitaire, the entire territory from Finland in the north to Romania in the south, standing between Western Europe and potential Bolshevik territorial ambitions.[12][13]

All three Baltic countries experienced a period of authoritarian rule by a head of state who had come to power after a bloodless coup: Antanas Smetona in Lithuania (1926-1940), Kārlis Ulmanis in Latvia (1934–1940), and Konstantin Päts during the “era of silence” (1934–1938) in Estonia, respectively. Some note that the events in Lithuania differed from the other two countries, with Smetona having different motivations as well as securing power 8 years before any such events in Latvia or Estonia took place. Despite considerable political turmoil in Finland no such events took place there. Finland did however get embroiled in a bloody civil war, something that did not happen in the Baltics.[14]

Some controversy surrounds the Baltic authoritarian régimes – due to the general stability and rapid economic growth of the period (even if brief), some commenters avoid the label “authoritarian”; others, however, condemn such an “apologetic” attitude, for example in later assessments of Kārlis Ulmanis.

Soviet and German Occupations, 1940–1991

In accordance with a secret protocol within the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 that divided Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence, the Soviet Army invaded eastern Poland in September 1939, and the Stalinist Soviet government coerced Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into “mutual assistance treaties” which granted USSR the right to establish military bases in these countries. In June 1940, the Red Army occupied all of the territory of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and installed new, pro-Soviet puppet governments. In all three countries simultaneously, rigged elections (in which only pro-Stalinist candidates were allowed to run) were staged in July 1940, the newly assembled “parliaments” in each of the three countries then unanimously applied to join the Soviet Union, and in August 1940 were incorporated into the USSR as the Estonian SSR, Latvian SSR, and Lithuanian SSR.

Repressions, executions and mass deportations followed after that in the Baltics.[17][18] The Soviet Union attempted to Sovietize its occupied territories, by means such as deportations and instituting the Russian language as the only working language. Between 1940 and 1953, the Soviet government deported more than 200,000 people from the Baltics to remote locations in the Soviet Union. In addition, at least 75,000 were sent to Gulags. About 10% of the adult Baltic population were deported or sent to labor camps.[19] (See June deportation, Soviet deportations from Estonia, Sovietization of the Baltic states)

During the occupation the Nazi authorities carried out ghettoisations and mass killings of the Jewish populations in Lithuania and Latvia.[20] Over 190,000 Lithuanian Jews, nearly 95% of Lithuania’s pre-war Jewish community, and 66,000 Latvian Jews were murdered. The German occupation lasted until late 1944 (in Courland, until early 1945), when the countries were reoccupied by the Red Army and Soviet rule was re-established, with the passive agreement of the United States and Britain (see Yalta Conference and Potsdam Agreement).

The forced collectivisation of agriculture began in 1947, and was completed after the mass deportation in March 1949. Private farms were confiscated, and farmers were made to join the collective farms. In all three countries, Baltic partisans, known colloquially as the Forest Brothers, Latvian national partisans, and Lithuanian partisans, waged unsuccessful guerrilla warfare against the Soviet occupation for the next eight years in a bid to regain their nations’ independence. The armed resistance of the anti-Soviet partisans lasted up to 1953. Although the armed resistance was defeated, the population remained anti-Soviet.

Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were considered to be under Soviet occupation by the United States, the United Kingdom,[21] Canada, NATO, and many other countries and international organizations.[22] During the Cold War, Lithuania and Latvia maintained legations in Washington DC, while Estonia had a mission in New York City. Each was staffed initially by diplomats from the last governments before USSR occupation.[23]

Restoration of Independence

In the late 1980s, a massive campaign of civil resistance against Soviet rule, known as the Singing revolution, began. On 23 August 1989, the Baltic Way, a two-million-strong human chain, stretched for 600 km from Tallinn to Vilnius. In the wake of this campaign, Gorbachev’s government had privately concluded that the departure of the Baltic republics had become “inevitable”.[24]

This process contributed to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, setting a precedent for the other Soviet republics to secede from the USSR. Soviet Union recognized the independence of three Baltic states on 6 September 1991. Troops were withdrawn from the region (starting from Lithuania) from August 1993. The last Russian troops were withdrawn from there in August 1994.[25]Skrunda-1, the last Russian military radar in the Baltics, officially suspended operations in August 1998.[26]

21st Century

All three are today parliamentary democracies, with unicameral parliaments elected by popular vote for four-year terms: Riigikogu in Estonia, Saeima in Latvia and Seimas in Lithuania. In Latvia and Estonia, the president is elected by parliament, while Lithuania has a semi-presidential system whereby the president is elected by popular vote. All are part of the European Union (EU) and members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), being the only post-soviet states to be so.

Each of the three countries has declared itself to be the restoration of the sovereign nation that had existed from 1918 to 1940, emphasizing their contention that Soviet domination over the Baltic states during the Cold War period had been an illegal occupation and annexation.

The same legal interpretation is shared by the United States, the United Kingdom, and most other Western democracies, who held the forcible incorporation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into the Soviet Union to be illegal. At least formally, most Western democracies never considered the three Baltic states to be constituent parts of the Soviet Union. Australia was a brief exception to this support of Baltic independence: in 1974, the Labor government of Australia did recognize Soviet dominion, but this decision was reversed by the next Australian Parliament.[27] Other exceptions included Sweden, which was the first Western country, and one of the very few to ever do so, to recognize the incorporation of the Baltic states into the Soviet Union as lawful.[28]

After the Baltic states had restored their independence, integration with Western Europe became a major strategic goal. In 2002, the Baltic governments applied to join the European Union and become members of NATO. All three became NATO members on 29 March 2004, and joined the EU on 1 May 2004.

Endnotes

- “Colombia and Lithuania join the OECD”. France 24. 30 May 2018.

- Republic of Estonia. “Baltic Cooperation”. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Lukoševičius, Viktoras; Duksa, Tomas. “ERATOSTHENES’ MAP OF THE OECUMENE”. Geodesy and Cartography. Taylor & Francis. 38 (2): 84.

- “Indo-European Etymology: Query result”. starling.rinet.ru.

- Dini, Pierto Umberto (2000) [1997]. Baltu valodas (in Latvian). Translated from Italian by Dace Meiere. Riga: Jānis Roze.

- Krauklis, Konstantīns (1992). Latviešu etimoloģijas vārdnīca (in Latvian). Vol. I. Rīga: Avots. pp. 103–104.

- Bojtar, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Central European University Press.

- Skutāns, Gints. “Latvija – jēdziena ģenēze”. old.historia.lv. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- l.l.b, charles mayo (1804). a compendious view of universal history. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (2006). The Life of Nelson. Bexley Publications.

- Maude, George (2010). Aspects of the Governing of the Finns. Peter Lang.

- Smele, John (1996). Civil war in Siberia: the anti-Bolshevik government of Admiral Kolchak, 1918–1920. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 305.

- Calvo, Carlos (2009). Dictionnaire Manuel de Diplomatie et de Droit International Public et Privé. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 246.

- “Why did Finland remain a democracy between the two World Wars, whereas the Baltic States developed authoritarian regimes?”. January 2004.

as [Lithuania] is a distinct case from the other two Baltic countries. Not only was an authoritarian regime set up in 1926, eight years before those of Estonia and Latvia, but it was also formed not to counter a threat from the right, but through a military coup d’etat against a leftist government. (…) The hostility between socialists and non-socialists in Finland had been amplified by a bloody civil war

- Kilin and Raunio (2007), p. 10

- Hough (2019).

- “These Names Accuse—Nominal List of Latvians Deported to Soviet Russia”. latvians.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Kangilaski, Jaak; Salo, Vello; Komisjon, Okupatsioonide Repressiivpoliitika Uurimise Riiklik (2005). The white book: losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes, 1940–1991. Estonian Encyclopaedia Publishers.

- “Communism and Crimes against Humanity in the Baltic states”. 13 April 1999. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- “Murder of the Jews of the Baltic States”. Yad Vashem.

- “Country Profiles: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania”. Foreign & Commonwealth Office – Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 31 July 2003. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- “U.S.-Baltic Relations: Celebrating 85 Years of Friendship”. U.S. Department of State. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- Norman Kempster, Annexed Baltic States : Envoys Hold On to Lonely U.S. Postings Archived 19 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, 31 October 1988. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- Beissinger, Mark R. (2009). “The intersection of Ethnic Nationalism and People Power Tactics in the Baltic States”. In Adam Roberts; Timothy Garton Ash (eds.). Civil resistance and power politics: the experience of non-violent action from Gandhi to the present. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 231–246.

- Pike, John. “Baltic Military District”. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- “SKRUNDA SHUTS DOWN. – Jamestown”. Jamestown. 1 September 1993. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- “The Latvians in Sydney”. Sydney Journal. 1. March 2008.

- Mart, Kuldkepp. “Swedish political attitudes towards Baltic independence in the short twentieth century”. Ajalooline Ajakiri. The Estonian Historical Journal (3/4).

Originally published by Wikipedia, 02.26.2003, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.