Understanding Sparta as dystopian does not require denying its achievements or ignoring its historical context. It requires acknowledging that effectiveness and ethical legitimacy are not synonymous.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Rethinking Sparta Beyond the Warrior Myth

Few ancient societies have been as persistently romanticized as Sparta. In popular memory and modern political rhetoric, the Spartan polis is often portrayed as a disciplined, egalitarian warrior state whose citizens sacrificed comfort for collective strength. This image derives partly from ancient admiration and partly from modern projection, but it obscures the deeper social reality of Sparta’s survival. As far as we know, Spartan stability did not emerge from civic harmony or shared virtue but from institutions deliberately shaped to manage domination over a subject population. Aristotle already recognized this dynamic when he argued that Spartan law was oriented less toward justice than toward preserving control, especially in a society where the citizen body ruled a vastly larger population of dependents.1

To describe Sparta as dystopian is not to impose a modern literary category anachronistically, but to use the term analytically. A dystopian society need not be chaotic or collapsing; it may function efficiently while relying on repression, surveillance, and violence as structural necessities. Sparta fits this definition with unusual clarity. Ancient sources describe how fear was cultivated deliberately through legal vulnerability, ritualized humiliation, and the normalization of violence against helots, practices that indicate terror was not an excess but a governing principle.2 The demographic imbalance between Spartiate citizens and helots created a permanent condition of insecurity that demanded constant enforcement, making coercion an everyday feature of social life rather than an emergency response.3

At the same time, Spartan citizens themselves lived under a regime of severe constraint. From early childhood, the agoge subjected boys to state-controlled education that prioritized obedience, endurance, and conformity over family bonds or intellectual cultivation. Individual choice, privacy, and economic autonomy were systematically curtailed in favor of permanent military readiness. Xenophon praised these arrangements as sources of strength, yet his account also reveals the degree to which Spartan life was stripped of civil freedom in comparison to other Greek poleis.4 Sparta thus functioned as a dual dystopia: overtly for the helots, whose lives were defined by coercion and fear, and structurally for citizens, whose identities were subsumed entirely into the needs of the state. Understanding Sparta in this way reframes it not as a heroic exception in Greek history but as an early example of how social order can be achieved through totalizing control and normalized violence.5

The Structural Foundations of Spartan Society

Spartan society was built on an unusually rigid political architecture that concentrated power while diffusing responsibility. The dual kingship, often misinterpreted as a balance against tyranny, functioned primarily as a military arrangement rather than a democratic safeguard. Two hereditary kings led armies and performed religious duties, but their authority was constrained by other institutions that ensured continuity rather than accountability. Real power rested in a small elite network that could mobilize force quickly and suppress dissent efficiently, an arrangement Aristotle regarded as structurally unstable precisely because it privileged endurance over justice.6 The system did not seek consensus. It sought control.

At the center of this structure stood the Gerousia, a council of elders composed of men over sixty, alongside the two kings. The Gerousia held extraordinary influence over legislation and judicial decisions, including capital cases, and its members were selected for life. This body embodied Spartan conservatism in its most literal sense, freezing political authority in the hands of aging elites whose interests were aligned with preserving existing hierarchies. While later admirers praised the Gerousia for its stability, its real function was to prevent structural change and suppress reformist pressures that might destabilize elite dominance.7 The result was a political culture deeply resistant to adaptation.

The Ephorate added another layer of control, one that outwardly appeared more representative but in practice intensified surveillance. Five ephors were elected annually and possessed sweeping powers, including the authority to oversee kings, enforce discipline, and declare war on the helot population. Their short terms did not democratize power but instead normalized arbitrary enforcement, allowing repression to be routinized rather than exceptional. Ancient sources note that ephors could act without formal trial, a feature that made fear an everyday instrument of governance rather than a response to crisis.8 This diffusion of coercive authority made accountability nearly impossible.

Underlying these political institutions was a stark demographic reality. Spartan citizens formed a small minority ruling over a vastly larger population of helots who worked the land and generated the surplus that sustained the state. As far as we know, this imbalance was not accidental but foundational. The entire political system was calibrated to manage the permanent threat of revolt posed by a subjugated majority. Modern scholarship has emphasized that Spartan militarism was not a cultural preference but a structural necessity dictated by this imbalance, tying internal governance directly to externalized violence.9 The state existed in a condition of permanent internal siege.

These institutions formed an integrated system whose primary objective was social control. The kings provided continuity, the Gerousia enforced conservatism, the ephors operationalized surveillance, and the army stood ready to suppress resistance. What emerges is not a mixed constitution aimed at balance, but a tightly interlocked mechanism designed to preserve elite dominance over both helots and citizens. Sparta’s famed stability was thus inseparable from its coercive foundations, revealing a society whose political strength depended on the normalization of fear and the systematic restriction of freedom.10

The Helot System: State-Enforced Terror as Social Policy

The helot system formed the dark core of Spartan society, supplying the labor that sustained the citizen class while simultaneously constituting its greatest perceived threat. Helots were not private slaves but state-owned serfs, tied to the land and compelled to deliver fixed agricultural quotas to their Spartan masters. Their legal status placed them outside the protections afforded to citizens and perioikoi, rendering them permanently vulnerable to coercion. Aristotle noted that this condition produced not stability but fear, as the ruling class lived in constant anxiety over revolt by a numerically superior population.11 The helot system thus fused economic exploitation with political insecurity, making repression an everyday necessity rather than an occasional response.

This insecurity was managed through the deliberate cultivation of terror. Ancient sources describe a range of practices designed to degrade and intimidate the helots, including forced displays of drunkenness and public humiliation intended to reinforce their subhuman status. Plutarch reports that helots could be beaten or killed without legal consequence, a condition that erased any meaningful boundary between discipline and brutality.12 Such practices were not informal excesses but culturally sanctioned behaviors that communicated a clear message: survival depended on submission. Violence functioned not merely as punishment but as pedagogy, teaching fear as a social norm.13

The most explicit expression of this policy was the Krypteia, an institution that blurred the line between military training and organized terror. Young Spartan men were sent into the countryside armed only with daggers and encouraged to murder helots deemed strong, defiant, or threatening. Thucydides recounts an episode in which helots were promised freedom for service and then systematically killed, an act that reveals the depth of Spartan paranoia and the instrumental use of deception.14 The Krypteia was not a secret aberration but a state-sanctioned mechanism for population control, embedding extrajudicial killing into the moral education of citizens.15

What distinguishes the helot system from other forms of unfree labor in the ancient world is the degree to which fear was institutionalized. Spartan society depended on a permanent state of internal war, renewed annually when the ephors formally declared war on the helots, thereby removing religious barriers to killing them.16 This ritualized declaration transformed violence into lawful routine and normalized terror as a governing strategy. The helot system was therefore not a regrettable byproduct of Spartan society but a central pillar of its survival, revealing a polity willing to sacrifice basic human security to preserve elite dominance.17

Childhood, the Agoge, and the Manufacturing of Obedience

From the moment of birth, Spartan children were subjected to state scrutiny in a manner unmatched elsewhere in the Greek world. Ancient sources describe how newborns were inspected by elders and exposed if judged physically unfit, a practice traditionally attributed to Lycurgus and reported by Plutarch.18 Whether every detail of this ritual was universally enforced remains debated, but its ideological significance is unmistakable. The family did not possess ultimate authority over the child. The state did. This early intervention signaled that individual life was conditional, valued only insofar as it served collective ends, and it established obedience to communal judgment as a foundational norm.19

At the age of seven, Spartan boys were removed from their households and enrolled in the agoge, the state-run system of education and training that defined citizenship. Xenophon praised this system as the source of Spartan strength, emphasizing its focus on discipline, endurance, and cohesion rather than literacy or intellectual cultivation.20 The agoge was not designed to produce reflective citizens but compliant bodies accustomed to command and hardship. Boys were organized into age cohorts, placed under constant supervision, and taught to value conformity over individuality. What other Greek poleis entrusted to families, Sparta claimed as a function of the state.21

Material deprivation formed a central feature of this training. Boys were deliberately underfed, poorly clothed, and exposed to physical discomfort as a means of cultivating endurance. Theft was encouraged, not as a lesson in morality, but as a test of cunning and self-reliance, with punishment reserved not for stealing but for being caught. Aristotle criticized this practice, arguing that it blurred ethical boundaries and habituated young citizens to deception rather than virtue.22 The agoge thus normalized rule-breaking when sanctioned by authority, reinforcing obedience to outcomes rather than to moral principles.23

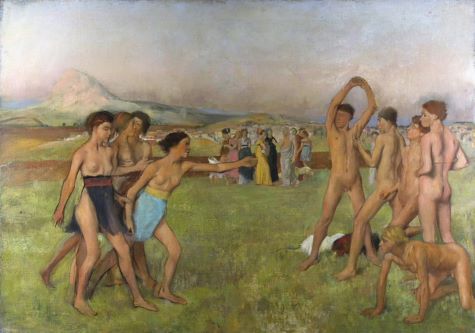

Violence also played a formative role in Spartan education. Corporal punishment was routine, and boys were encouraged to endure pain without complaint. Ritualized contests at the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia, where youths were whipped before an audience, exemplified the public celebration of suffering as a civic virtue. Plutarch records these spectacles with admiration, yet their pedagogical purpose is clear: pain was transformed into proof of loyalty, and endurance became a measure of worth.24 The internalization of violence prepared citizens to accept brutality as normal, both toward themselves and toward others.

Equally important was the agoge’s function as a system of surveillance. Older youths monitored younger ones, peers reported on peers, and authority was deliberately fragmented to ensure constant observation. Modern historians have emphasized that this structure trained citizens not only to obey commands but to police one another, extending state control into everyday interactions.25 The result was a society in which autonomy was not merely restricted but conceptually alien, replaced by an ethic of total transparency to communal judgment.26

By the time Spartan males reached adulthood, obedience had been rendered habitual. The agoge did not simply teach skills; it reshaped identity. Citizens emerged conditioned to accept hierarchy, suppress dissent, and subordinate personal interest to perceived necessity. This process reveals that the Spartan dystopia was not imposed solely through overt force but reproduced through education that aligned psychological formation with political domination. The manufacturing of obedience in childhood ensured that coercion would persist without constant enforcement, binding the survival of the state to the internal discipline of its citizens.27

Total Militarization and the Erasure of Civil Life

Spartan society subordinated virtually every dimension of life to the demands of military readiness. Unlike other Greek poleis, where warfare punctuated civic existence, Sparta organized civic existence around the anticipation of war. Military obligation did not begin at adulthood nor end with active service; it structured the entire life course of male citizens. Xenophon emphasized that Spartans were never released from discipline, a condition he admired but which also reveals the absence of any meaningful boundary between civilian and military life.28 War was not an episode. It was the organizing principle of the state.

This militarization reshaped daily routines and social relationships. Spartan men were required to eat in communal messes, the syssitia, well into adulthood, severing the household as a center of private life. Participation in these messes was mandatory, and failure to contribute could result in loss of citizenship, effectively making economic autonomy a prerequisite for political existence. Aristotle criticized this system for undermining family life and concentrating loyalty upward toward the state rather than outward toward civic reciprocity.29 The structure discouraged private bonds that might compete with collective obedience.

Marriage and reproduction were likewise regulated in service of military goals. Spartan men often lived in barracks until their thirties, permitted only limited contact with their wives during early marriage. This arrangement was intended to prioritize physical discipline and group cohesion over domestic stability. Ancient sources suggest that reproduction itself was treated as a civic duty, with marriage practices shaped by concerns about producing physically robust offspring rather than fostering emotional or familial intimacy.30 The state thus intruded into the most personal aspects of life, framing biological continuity as a matter of public security rather than private choice.31

The suppression of civil life extended to economic and cultural expression. Spartan citizens were prohibited from engaging in trade or craftsmanship, activities delegated to perioikoi and helots, while luxury and artistic production were actively discouraged. Coinage was restricted and deliberately inconvenient, limiting accumulation and exchange. Plutarch presents these measures as safeguards against corruption, yet their effect was to narrow the range of permissible identity and aspiration.32 Spartan culture valued uniformity over creativity, endurance over reflection, and discipline over deliberation, leaving little space for civil institutions independent of military purpose.33

These practices produced a society in which citizenship was defined almost exclusively by readiness for violence. The erasure of civil life was not accidental but structural, ensuring that no alternative loyalties, values, or forms of authority could emerge alongside the military state. Sparta’s strength rested on this totalization, but at the cost of suppressing the very features that distinguished civic life elsewhere in Greece. What remained was a polity that functioned efficiently yet narrowly, revealing how complete militarization can hollow out civil existence while maintaining outward stability.34

Gender, Control, and the Illusion of Female Freedom

Spartan women have often been portrayed as unusually free when compared with their counterparts elsewhere in the Greek world. Ancient authors noted their visibility in public life, physical training, and relative independence in managing property, features that later commentators interpreted as evidence of gender equality. Yet this apparent autonomy existed within a society whose overriding concern was military survival. As far as we know, Spartan women’s roles were expanded not to enhance personal freedom but to serve the reproductive and economic needs of the state. Their visibility did not signal liberation from control but a redirection of control toward state-defined ends.35

One of the most frequently cited indicators of Spartan women’s freedom was their right to own and inherit property. By the classical period, women are thought to have controlled a substantial portion of Spartan land, a development that alarmed Aristotle, who blamed it for social imbalance and declining citizen numbers.36 This economic authority, however, did not translate into political power or personal autonomy. Women’s property rights functioned to stabilize elite households and ensure the continuity of the citizen class, especially in a society where male mortality and prolonged military service disrupted inheritance patterns.37 Economic agency thus reinforced, rather than challenged, the existing social order.

Physical education for women offers another example of autonomy constrained by purpose. Spartan girls participated in athletic training, a practice that shocked other Greeks and contributed to Sparta’s reputation for female freedom. Plutarch explains this training explicitly as preparation for childbirth, intended to produce stronger offspring for the state.38 The cultivation of strength was not an end in itself but a means of ensuring reproductive success. Female bodies, like male ones, were treated as instruments of state policy, valued for their contribution to military continuity rather than personal development.39

Marriage and sexuality were likewise regulated according to collective priorities. Spartan marriage customs, including delayed cohabitation and sanctioned extramarital arrangements in certain circumstances, reflected concern with producing physically capable children rather than enforcing monogamous norms. Ancient sources describe these practices without moral condemnation, revealing a society in which intimacy was subordinated to utility.40 Women’s sexual agency operated within boundaries defined by demographic anxiety and state interest, reinforcing the illusion of freedom while constraining genuine choice.41

The result was a system in which Spartan women occupied a paradoxical position. They appeared empowered when measured against the restrictive norms of other Greek societies, yet their lives were structured around expectations that left little room for self-determination. Their relative autonomy was tolerated, even encouraged, precisely because it served the needs of a militarized state. Spartan gender relations thus illustrate how expanded roles can coexist with deep forms of control, producing an illusion of freedom that masked a broader dystopian logic of social engineering.42

Violence as Normalcy: Ethical Deformation in Spartan Culture

Violence in Sparta was not merely a response to external threats but a normalized feature of social life that shaped moral perception from an early age. As far as we know, Spartan institutions did not treat violence as an unfortunate necessity but as a formative good, integral to the preservation of order. Ancient observers repeatedly noted the casual acceptance of cruelty within Spartan society, particularly toward helots, as evidence of strength rather than moral failing. Aristotle’s criticism of Spartan education underscores this point, arguing that habituation to violence distorted ethical judgment by prioritizing domination over justice.43 What emerged was not simply a violent society, but one in which violence carried moral legitimacy.

This normalization was reinforced through ritual and spectacle. Public beatings, endurance contests, and sanctioned cruelty were staged before audiences, transforming suffering into communal affirmation. The whipping of youths at the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia exemplified this dynamic, where pain became a public measure of worth and loyalty. Plutarch’s account treats these rituals as admirable tests of character, yet their social function was unmistakable: they bound citizens together through shared participation in sanctioned harm.44 Violence was thus aestheticized, stripped of ethical ambiguity, and recast as virtue.

The ethical consequences of this conditioning extended beyond ritual into everyday conduct. Spartan citizens were encouraged to display harshness toward helots and emotional restraint toward one another, fostering a culture in which empathy was systematically suppressed. Modern scholars have argued that this environment narrowed the moral imagination of citizens, limiting their capacity to recognize injustice outside the framework of state necessity.45 What might elsewhere have been perceived as cruelty was, in Sparta, reclassified as discipline. Moral language itself was reshaped to accommodate domination.

This deformation was particularly evident in Spartan attitudes toward deception and killing. The Krypteia, which rewarded stealthy murder of helots, blurred the boundary between civic duty and criminality. Thucydides’ account of the mass disappearance of helots following promises of emancipation reveals how deeply ingrained such practices were.46 Deception and extrajudicial killing were not aberrations but accepted tools of governance, undermining any coherent ethical distinction between war and peace, or justice and expedience.47

Over time, this moral landscape produced citizens who were disciplined, obedient, and effective, but ethically constrained. Spartan society succeeded in generating stability through the internalization of violence, yet this success came at the cost of moral flexibility and humane judgment. The normalization of cruelty eroded the possibility of ethical dissent, ensuring that violence reproduced itself without constant coercion. In this sense, Sparta’s dystopian character lay not only in what it did to its victims but in what it made of its citizens, revealing how sustained violence can deform ethical life while masquerading as civic virtue.48

Counterarguments: Stability, Equality, and Spartan Exceptionalism

Defenders of Sparta have long argued that its social order, however harsh, produced an unusual degree of internal stability. Ancient admirers such as Xenophon emphasized the longevity of Spartan institutions, contrasting their endurance with the volatility of democratic poleis like Athens. From this perspective, repression appears not as dystopian excess but as the price of cohesion. Yet stability alone is an insufficient metric for evaluating a society’s character. As Aristotle observed, endurance achieved through coercion does not constitute justice, particularly when stability depends on the perpetual suppression of a subject population.49 What appears orderly on the surface conceals an ongoing condition of structural violence.

A related argument points to the supposed equality among Spartan citizens. Unlike other Greek states marked by sharp wealth disparities, Sparta is often described as having minimized economic inequality through communal practices and austere norms. This image, however, collapses under closer scrutiny. Equality existed only within a narrowly defined citizen class that excluded women from political power and reduced helots to instruments of labor. Modern scholarship has demonstrated that even among citizens, disparities in land ownership and status persisted, undermining claims of genuine egalitarianism.50 Spartan equality functioned less as a moral principle than as a mechanism for reinforcing elite solidarity against internal and external threats.51

Spartan exceptionalism has also been defended on cultural grounds. Admirers argue that Sparta should be judged on its own terms rather than by external standards, emphasizing its distinct values and priorities. While cultural specificity matters, it cannot exempt a society from ethical evaluation altogether. To acknowledge difference is not to suspend judgment. The systematic use of terror, the institutionalization of child removal, and the normalization of extrajudicial killing are not rendered benign by cultural context. As historians have noted, appeals to exceptionalism often serve to obscure power relations by reframing domination as tradition.52

Ultimately, these counterarguments reveal less about Spartan virtue than about the criteria used to assess political success. Stability, discipline, and cohesion are not neutral goods when they are achieved through fear and exclusion. Sparta did not fail because it was unstable or chaotic. It succeeded precisely because it embedded repression so deeply into its institutions that resistance became nearly unthinkable. Recognizing this does not require denying Sparta’s effectiveness, but it does require acknowledging the human cost of that effectiveness. In this sense, Spartan exceptionalism reinforces rather than undermines the argument that the polis functioned as a dystopian society.53

Comparative Perspective: Sparta and the Logic of Dystopian Control

When examined comparatively, Sparta reveals structural patterns that recur across societies commonly identified as dystopian, even when separated by time, culture, and technology. These patterns include the concentration of authority, the erosion of private life, and the use of fear as a stabilizing force. What distinguishes Sparta is not that it invented these mechanisms, but that it integrated them early and thoroughly into the fabric of civic life. As far as we know, few ancient societies so explicitly organized their institutions around permanent internal threat, making control an everyday condition rather than an emergency response.54 This structural orientation aligns Sparta less with idealized Greek poleis than with later regimes built on surveillance and coercion.

A defining feature of dystopian control is the substitution of ideology for deliberation. In Sparta, civic values were not debated but imposed through education, ritual, and repetition. The agoge functioned as a closed system in which alternative modes of thought were systematically excluded, producing citizens who experienced obedience as virtue rather than constraint. Comparative political theory has emphasized that such systems do not merely restrict dissent; they eliminate the conceptual tools required to imagine it.55 Sparta’s educational regime thus parallels later dystopian models in which ideology becomes self-reinforcing through socialization rather than overt propaganda.56

Another common feature is the deliberate collapse of boundaries between public and private life. In Sparta, communal meals, regulated marriage, and constant peer surveillance ensured that personal identity remained transparent to the state. This transparency was not incidental but functional, reducing the likelihood of subversive networks or private loyalties. Historians have noted that the suppression of privacy often accompanies societies facing perceived existential threats, as secrecy itself becomes suspect.57 Sparta’s internal logic mirrored this pattern, treating autonomy as a liability rather than a right.

Fear also operates comparably across dystopian systems. In modern contexts, fear is often mediated through bureaucracy or technology. In Sparta, it was enacted physically and ritualistically. The annual declaration of war against the helots and the sanctioned violence of the Krypteia institutionalized terror as a civic tool, ensuring that domination remained visible and immediate. Thucydides’ account of Spartan actions toward helots demonstrates how fear was maintained not through constant force but through unpredictable brutality.58 This reliance on uncertainty as a governing strategy resonates with later dystopian regimes that use arbitrariness to suppress resistance.59

Sparta also illustrates how dystopian systems often rely on partial inclusion to sustain legitimacy. Spartan citizens enjoyed privileges denied to helots and perioikoi, fostering loyalty through comparative advantage rather than universal freedom. This stratification created internal investment in the system, as citizens perceived their status as contingent on its continuation. Political theorists have long observed that such tiered inclusion is a powerful stabilizer, binding beneficiaries to structures that are oppressive overall.60 Sparta’s durability depended on this dynamic, ensuring that dissent remained fragmented and self-limiting.

Viewed comparatively, Sparta emerges not as an anomaly but as an early instantiation of a recurring logic of control. Its institutions demonstrate how societies can achieve order through fear, cohesion through repression, and stability through ethical contraction. The absence of modern technology does not diminish the relevance of this comparison; it sharpens it. Sparta shows that dystopian systems do not require advanced surveillance or mass communication. They require only the systematic alignment of power, ideology, and socialization. In this sense, Sparta offers a historical template for understanding how dystopian control functions across time, reminding us that such systems are not aberrations but recurring possibilities within human political organization.61

Conclusion: Sparta as a Warning, Not a Model

Sparta’s endurance has long tempted admirers to mistake survival for virtue. Its institutions produced cohesion, discipline, and military effectiveness, but these qualities were purchased through the systematic restriction of freedom and the normalization of violence. As far as we know, Sparta did not collapse because it was chaotic or dysfunctional. It collapsed because its rigid social architecture could not adapt to changing political and economic realities. Aristotle already warned that a society organized solely around domination and military readiness would struggle to sustain itself once its external conditions shifted.62 Stability achieved through repression proved brittle when fear alone could no longer hold the system together.63

Understanding Sparta as dystopian does not require denying its achievements or ignoring its historical context. It requires acknowledging that effectiveness and ethical legitimacy are not synonymous. Spartan society succeeded in producing obedient citizens and suppressing revolt, but it did so by hollowing out civil life and narrowing moral horizons. Modern scholarship has emphasized that the same institutions that generated cohesion also stifled innovation, discouraged dissent, and limited Sparta’s capacity to respond creatively to crisis.64 The very mechanisms that preserved order in one era undermined resilience in the next.

Sparta’s deeper significance lies in what it reveals about power rather than in what it offers as an example. The polis demonstrates how societies can normalize coercion by embedding it into education, ritual, and everyday life, transforming violence from an exception into an ethical baseline. This process does not require advanced technology or explicit ideology. It requires only the consistent alignment of fear, socialization, and authority. Comparative historians and political theorists have repeatedly noted that such systems recur whenever security is elevated above humanity as a guiding value.65 Sparta stands as an early, stark illustration of this logic.

To treat Sparta as a model is therefore to misunderstand both its success and its failure. Its legacy is not one of admirable discipline but of cautionary clarity. Sparta reminds us that social order can be achieved at the expense of freedom, that cohesion can coexist with cruelty, and that stability can mask profound injustice. As far as we know, societies that embrace these trade-offs may endure for a time, but they do so by sacrificing the very qualities that allow human communities to flourish. In this sense, Sparta endures not as an ideal to emulate, but as a warning written into the historical record.66

Appendix

Footnotes

- Aristotle, Politics, trans. H. Rackham (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932), 1269a–1271b.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, in Parallel Lives, trans. Bernadotte Perrin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914), 28–29.

- Paul Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia: A Regional History 1300–362 BC (London: Routledge, 1979), 85–92.

- Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, trans. E. C. Marchant (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1925), 1–4.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, trans. C. F. Smith (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1919), 4.80.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1270a–1271b.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 6–7.

- Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, 8.

- Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia, 72–80.

- Stephen Hodkinson, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta (London: Duckworth, 2000), 38–44.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1269a–1270a.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 28.

- Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia, 84–92.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 4.80.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 28–29; Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, 2–3.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 28.

- Hodkinson, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta, 35–44.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 16.

- Hodkinson, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta, 58–61.

- Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, 2–4.

- Cartledge, Spartan Reflections (London: Duckworth, 2001), 85–89.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1336a–1337a.

- Nigel Kennell, The Gymnasium of Virtue: Education and Culture in Ancient Sparta (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 47–52.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 18.

- Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia, 112–118.

- Kennell, The Gymnasium of Virtue, 73–77.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1269b–1270a.

- Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, 4–5.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1271a–1272b.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 15–16.

- Hodkinson, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta, 74–80.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 9–10.

- Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia, 156–162.

- Kennell, The Gymnasium of Virtue, 101–108.

- Sarah B. Pomeroy, Spartan Women (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 3–7.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1270a–1271b.

- Hodkinson, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta, 81–88.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 14–15.

- Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia, 168–172.

- Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, 1–2.

- Pomeroy, Spartan Women, 60–66.

- Cartledge, Spartan Reflections, 112–118.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1337a–1338b.

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 18.

- Kennell, The Gymnasium of Virtue, 121–127.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 4.80.

- Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia, 95–101.

- Hodkinson, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta, 103–108.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1271b–1273a.

- Hodkinson, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta, 62–70.

- Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia, 145–151.

- Pomeroy, Spartan Women, 143–148.

- Cartledge, Spartan Reflections, 176–181.

- Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia, 90–98.

- Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1951), 308–315.

- Kennell, The Gymnasium of Virtue, 131–136.

- Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1975), 195–203.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 4.80.

- Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 420–428.

- James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 3–8.

- Hodkinson, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta, 109–115.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1271b–1273a.

- Cartledge, Spartan Reflections, 182–186.

- Hodkinson, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta, 118–124.

- Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 460–468.

- Scott, Seeing Like a State (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 4–7.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1951.

- Aristotle. Politics. Translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932.

- Cartledge, Paul. Sparta and Lakonia: A Regional History 1300–362 BC. London: Routledge, 1979.

- ———. Spartan Reflections. London: Duckworth, 2001.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1975.

- Hodkinson, Stephen. Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta. London: Duckworth, 2000.

- Kennell, Nigel. The Gymnasium of Virtue: Education and Culture in Ancient Sparta. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Plutarch. Life of Lycurgus. In Parallel Lives. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914.

- Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

- ———. Seeing Like a State. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by C. F. Smith. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1919.

- Xenophon. Constitution of the Lacedaemonians. Translated by E. C. Marchant. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1925.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.