The abuses suffered by the working class during America’s Gilded Age were the logical outcome of an economic order that prioritized output, profit, and expansion over human well-being.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Industrial Abundance and Human Deprivation

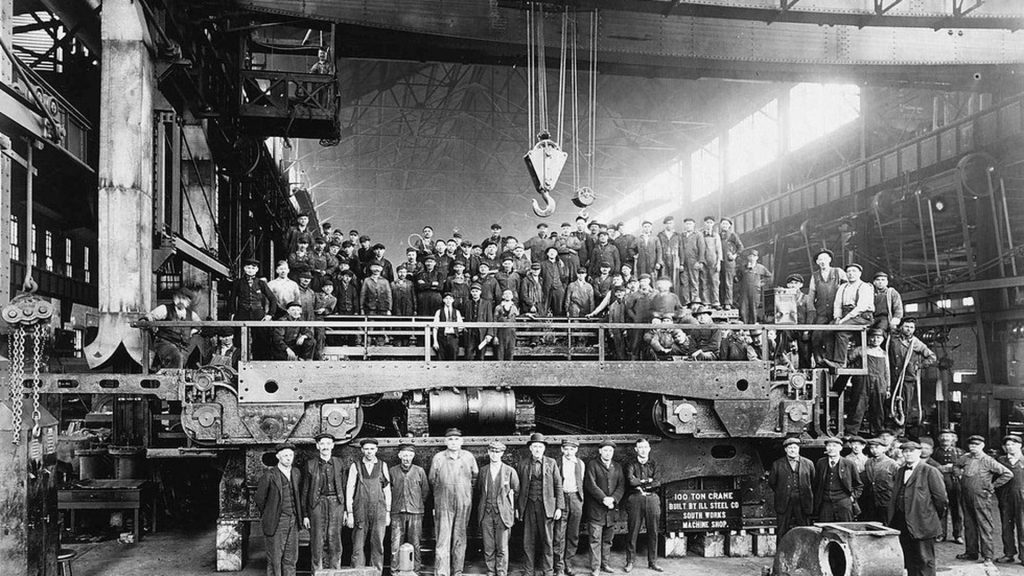

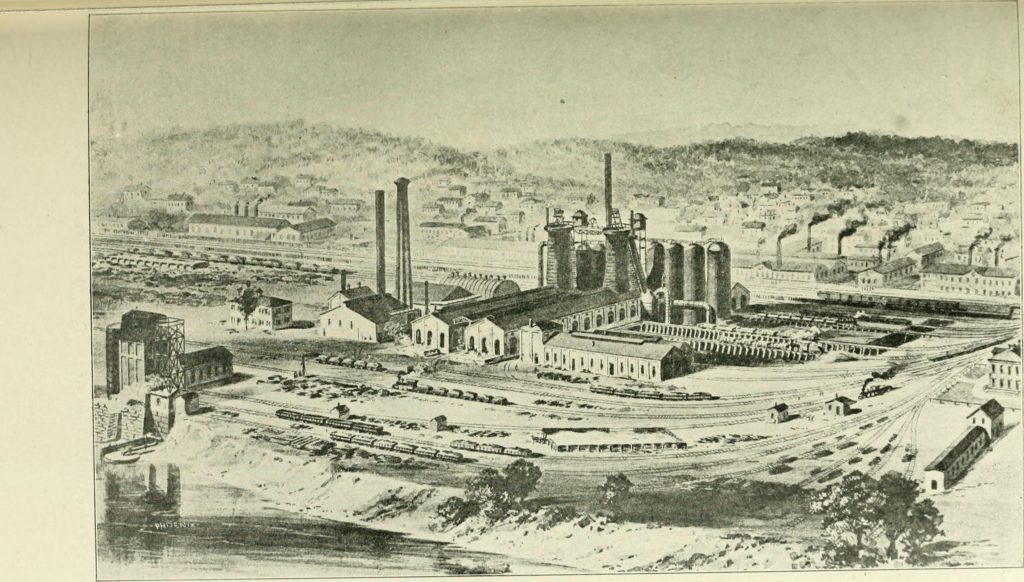

In the final decades of the nineteenth century, the United States experienced an economic transformation of unprecedented scale. Railroads stitched together distant regions, factories multiplied along urban corridors, and industrial output surged to levels that astonished contemporaries at home and abroad. Steel, coal, textiles, and manufactured goods poured from mills and workshops, fueling national wealth and elevating a small class of industrialists to extraordinary prominence. Yet this expansion rested upon a labor system that extracted human effort at immense cost, converting working-class bodies into expendable instruments of production rather than beneficiaries of progress.

For millions of laborers, industrial growth translated not into security but into prolonged exhaustion and precarity. Workers routinely labored ten to sixteen hours a day, six days a week, for wages insufficient to sustain a household without the earnings of spouses and children. Industrial employment rarely offered stability. Layoffs during downturns, wage cuts during periods of expansion, and the absence of employer responsibility for injury or death left workers perpetually vulnerable. Government investigations and reformers’ accounts repeatedly documented a labor regime in which survival depended on constant employment, regardless of physical toll or personal risk.1

The material conditions of industrial labor further underscored the imbalance between economic abundance and human deprivation. Factories, mines, and mills operated with minimal safety oversight, exposing workers to unguarded machinery, toxic air, inadequate lighting, and relentless repetition. Injuries were frequent, fatalities common, and compensation rare. Courts consistently favored employers, treating accidents as unfortunate but unavoidable byproducts of modern industry rather than preventable failures of management. In this environment, laborers were not merely underpaid. They were rendered legally and socially disposable.

Nowhere was this disposability more apparent than in the treatment of immigrants and children. Immigrant workers confronted language barriers, ethnic discrimination, and punitive wage systems that deducted pay for missed quotas or alleged inefficiency, often without explanation or recourse. Children labored alongside adults in factories and mines, performing dangerous tasks that stunted bodies and curtailed education. Their employment was not an aberration but a structural necessity within a wage system that required entire families to work in order to eat. Contemporary observers documented these practices with increasing alarm, recognizing that industrial capitalism had absorbed childhood itself into the machinery of production.2

The abuses of the Gilded Age working class were therefore not incidental excesses awaiting correction. They were fundamental to the organization of industrial labor and the concentration of wealth that defined the era. By examining long hours, unsafe workplaces, child labor, immigrant exploitation, mechanized deskilling, and economic insecurity together, what follows argues that Gilded Age prosperity was inseparable from the systematic degradation of labor. Industrial abundance did not merely coexist with human deprivation. It depended upon it.

The Architecture of Long Hours and Meager Wages

Industrial labor during the Gilded Age was structured around extreme hours that pushed the limits of human endurance. Factory and mill workers commonly labored ten to twelve hours a day, while miners and railroad workers frequently worked even longer shifts, especially during peak production periods. Six-day workweeks were standard, and seven-day schedules were not uncommon in industries where machinery ran continuously. These hours were not negotiated but imposed, enforced by supervisors and reinforced by the ever-present threat of replacement in oversupplied labor markets. Contemporary labor reports consistently described exhaustion as an ordinary condition of industrial employment rather than an exception.3

Despite these hours, wages rarely provided subsistence for a single worker, let alone a family. Industrial pay scales were deliberately calibrated to keep labor costs low in competitive markets, producing a system in which survival required multiple earners within a household. Married women and children entered wage labor not as a supplement but as a necessity. Census data and factory surveys reveal that family income often depended on the combined wages of fathers, mothers, and children, binding entire households to industrial schedules and erasing meaningful distinctions between domestic life and wage labor.4 This structure ensured a steady supply of compliant workers while transferring the social costs of poverty onto families themselves.

Wage instability further compounded hardship. Pay was frequently docked for missed quotas, machine downtime, or perceived inefficiency, practices that left workers unable to predict weekly income. Piece-rate systems intensified this insecurity by tying earnings to output under conditions workers did not control, such as machinery speed or material quality. Employers framed these practices as incentives for productivity, but laborers experienced them as mechanisms of discipline that punished fatigue, illness, or injury. The absence of minimum wage standards or enforceable contracts meant that workers bore the full risk of fluctuating demand while employers retained flexibility and profit.5

The combination of long hours and inadequate wages was not accidental but integral to industrial capitalism’s expansion. By extracting maximum labor time while minimizing compensation, employers sustained high output and low costs in fiercely competitive markets. Reformers recognized that this system did more than impoverish workers materially. It reordered time itself, leaving little space for rest, education, or civic life. Long hours and meager wages thus formed the foundation upon which other abuses rested, binding workers to a cycle of exhaustion that made resistance economically perilous and socially costly.6

Dangerous Workplaces and the Normalization of Injury

Industrial workplaces during the Gilded Age were defined by physical danger that was widely acknowledged yet rarely addressed. Factories and mills operated with unguarded belts, exposed gears, and cutting blades placed within inches of workers’ bodies, conditions documented repeatedly by state labor investigators. Accidents involving crushed limbs, scalping, and amputations were common, particularly among inexperienced workers assigned to fast-moving machinery without training or protective equipment.7 The expectation was not that machines would be made safer, but that workers would adapt themselves to hazardous environments or be replaced when injured.

Environmental conditions compounded these mechanical dangers. Poor lighting obscured moving parts and walkways, while inadequate ventilation exposed workers to dust, fumes, and chemical vapors throughout long shifts. Textile workers inhaled cotton and wool fibers that accumulated in the lungs, while miners labored in air thick with coal dust and gas, contributing to chronic respiratory disease and sudden explosions.8 Factory inspection reports repeatedly warned that many of these hazards were preventable through basic safeguards, a conclusion that undercut claims that industrial accidents were inevitable byproducts of progress.

When injuries occurred, employers were rarely held responsible. Courts routinely applied legal doctrines that insulated companies from liability, including the fellow-servant rule and assumptions of risk, which held that workers accepted danger by entering industrial employment.9 These rulings transformed accidents caused by unsafe machinery or overcrowded conditions into matters of individual misfortune rather than employer negligence. Injured workers faced substantial legal barriers when seeking compensation, as they were required to prove fault while lacking both financial resources and access to corporate records.

The consequences of injury extended beyond the workplace. Workers disabled by industrial accidents were frequently dismissed immediately, as employers bore no obligation to provide compensation, medical care, or continued employment.10 Without savings or insurance, injured laborers often became dependent on family members, forcing spouses and children to increase their hours or enter wage labor prematurely. Reformers documented numerous cases in which a single workplace injury initiated long-term household impoverishment, demonstrating how physical harm translated directly into economic ruin.

Over time, the sheer frequency of industrial injury normalized bodily harm as a feature of modern labor. Newspapers reported deaths and maimings in statistical language that reduced suffering to numbers, while employers framed accidents as unavoidable costs of efficiency. This normalization dulled public outrage and reinforced the idea that workers were expendable inputs rather than protected participants in economic life. By treating injury as inevitable and compensation as optional, industrial capitalism embedded violence into everyday labor, making physical risk an accepted price of prosperity rather than a condition demanding structural reform.11

Child Labor and the Destruction of Childhood

Child labor was not a marginal or exceptional feature of the Gilded Age economy. By the late nineteenth century, hundreds of thousands of children were employed in factories, mills, mines, and workshops, often beginning work before adolescence. Census data from the period recorded children as young as eight engaged in industrial labor, while reformers documented even younger children working informally or under falsified ages.12 These children were not performing light or transitional tasks. They labored alongside adults in environments shaped by speed, danger, and relentless repetition.

Economic necessity drove this exploitation. Wages paid to adult male workers were frequently insufficient to sustain a household, compelling families to rely on the earnings of wives and children. In textile towns and mining regions, family survival depended on multiple incomes pooled together, binding children to wage labor as a matter of subsistence rather than choice. Investigations by labor bureaus repeatedly emphasized that parents sent children to work not out of indifference, but because starvation was the alternative.13 This reality undermines narratives that frame child labor as a cultural preference rather than a structural consequence of industrial poverty.

The work assigned to children was often among the most dangerous in industrial settings. In mills, children crawled beneath moving machinery to clear debris, risking crushing injuries and scalping. In coal mines, boys known as breakers sorted coal in poorly lit spaces thick with dust, a task that damaged lungs and caused frequent accidents.14 Factory inspectors noted that children were especially vulnerable due to smaller size, fatigue, and limited awareness of hazards, yet employers valued them precisely because they could be paid less and disciplined more easily.

Beyond physical danger, industrial labor reshaped childhood itself. Long hours left little time for rest, play, or education, and many working children attended school irregularly or not at all. Reformers observed that exhaustion dulled concentration and stunted intellectual development, while repetitive labor narrowed future prospects by replacing education with early specialization in unskilled tasks.15 Childhood, in this context, ceased to function as a protected stage of development and instead became an early entry point into economic exploitation.

The legal framework of the era offered children little protection. Child labor laws, where they existed, were weakly enforced or riddled with exemptions that allowed employers to evade restrictions. Birth records were often absent or ignored, making age verification difficult. Employers routinely falsified documentation or relied on parental consent obtained under economic duress.16 The result was a regulatory environment that normalized child labor while projecting an illusion of reform through unenforced statutes.

Reform movements eventually mobilized public opposition to child labor, using photography, investigative journalism, and testimony to expose its human cost. Yet meaningful restrictions emerged slowly and unevenly, often resisted by industrialists who argued that regulation threatened economic growth. The persistence of child labor into the early twentieth century reveals how deeply it was embedded within the wage system of the Gilded Age. Children were not incidental victims of industrialization. They were integral to its functioning, their labor quietly underwriting the nation’s ascent to industrial power.17

Immigrant Labor and the Politics of Disposability

Immigrant workers formed the backbone of Gilded Age industrial labor, supplying the manpower required to sustain rapid expansion in factories, mines, railroads, and construction. By the late nineteenth century, newly arrived immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were disproportionately concentrated in the most dangerous and lowest-paid occupations, a pattern confirmed by census data and labor surveys.18 Employers actively recruited immigrant labor precisely because newcomers possessed limited bargaining power, lacked familiarity with American labor norms, and were often desperate for immediate employment upon arrival.

Language barriers and ethnic discrimination intensified this vulnerability. Immigrant workers frequently received instructions they could not fully understand, increasing the likelihood of workplace accidents and disciplinary penalties. Factory rules were commonly posted only in English, and failure to meet production quotas often resulted in wage deductions or dismissal rather than accommodation. Contemporary investigations documented instances in which immigrants lost pay for alleged inefficiency without explanation or recourse, reinforcing a labor regime in which misunderstanding became a punishable offense rather than a condition to be remedied.19

Wage systems further entrenched immigrant disposability. Piece-rate pay and subcontracting arrangements shifted economic risk onto workers, while deductions for damaged materials or missed quotas reduced already minimal earnings. Employers justified these practices as neutral measures of productivity, yet labor reformers observed that immigrant workers bore the brunt of such penalties due to unfamiliarity with machinery and expectations.20 In effect, the wage structure treated immigrants as infinitely replaceable inputs, interchangeable and expendable within a vast labor pool.

The absence of legal protection compounded these conditions. Immigrant workers rarely pursued claims against employers, deterred by language barriers, fear of dismissal, and hostility within courts that often favored corporate defendants. Nativist rhetoric portrayed immigrants as transient and inferior, reinforcing the notion that they were unsuited for long-term security or civic inclusion.21 Within this framework, disposability was not merely an economic condition but a political one, sustained by cultural narratives that justified exploitation while denying immigrant workers recognition as full participants in American industrial society.

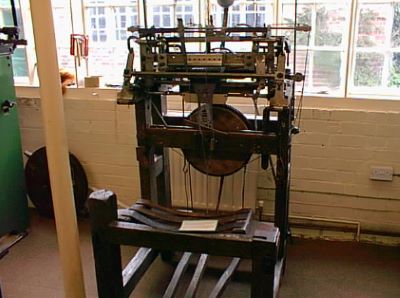

Mechanization and the Devaluation of Skill

Mechanization transformed the nature of work during the Gilded Age by breaking complex crafts into simplified, repetitive tasks. Skilled trades that once required years of apprenticeship were reorganized around machines that reduced labor to a narrow sequence of motions. Employers increasingly designed production processes so that workers needed only minimal training, allowing them to be hired quickly and replaced easily. Contemporary observers noted that this transformation severed the connection between skill and economic security, eroding the bargaining power that skilled workers had previously exercised.22

The division of labor intensified this process. Industrial managers embraced efficiency models that fragmented production into discrete tasks, each performed repeatedly by a different worker. This system maximized output but stripped labor of autonomy and meaning, as workers no longer controlled the pace or substance of their work. Accounts from machinists and metalworkers describe how mechanization reduced judgment and craftsmanship to obedience and endurance, turning labor into a mechanical extension of industrial systems rather than a skilled human activity.23

Deskilling also reshaped workers’ psychological experience of labor. Repetitive tasks performed over long hours produced fatigue, boredom, and alienation, conditions early social critics linked to declining morale and increased workplace accidents. Reformers warned that monotonous labor not only damaged bodies but diminished intellectual engagement, leaving workers disconnected from both the products of their labor and the broader civic world.24 These effects were especially pronounced among younger workers, whose early exposure to mechanized routines narrowed future occupational possibilities.

Employers defended mechanization as a necessary response to competition and technological progress, yet its social consequences were unevenly distributed. While owners and managers benefited from higher productivity and lower labor costs, workers absorbed the loss of skill, status, and security. Mechanization thus functioned not merely as a technological advance but as a tool of labor control, reinforcing a system in which workers were valued for compliance rather than expertise.25 The devaluation of skill became a cornerstone of industrial labor relations, reshaping power dynamics well beyond the factory floor.

Replaceability and Economic Precarity

The defining condition of Gilded Age labor was pervasive insecurity rather than any single abuse. Workers could be dismissed without notice, explanation, or compensation, creating an employment system in which jobs were always provisional. Economic downturns, seasonal slowdowns, or minor conflicts with supervisors frequently resulted in immediate termination. Labor investigators and reformers repeatedly noted that dismissal functioned as a disciplinary tool, reinforcing compliance through the constant threat of unemployment rather than formal coercion.26

At-will employment norms intensified this precarity. Employers were not required to provide severance, unemployment assistance, or continued wages during illness or injury, leaving workers fully exposed to sudden income loss. A laborer who missed shifts due to sickness or exhaustion risked permanent replacement, especially in industries with surplus labor pools. Contemporary legal analyses emphasized that this system shifted all economic risk onto workers while shielding employers from responsibility during disruption or downturn.27

Economic crises exposed the fragility of working-class life most starkly. During financial panics in the late nineteenth century, layoffs spread rapidly across industrial centers, swelling the ranks of the unemployed within weeks. Unemployment statistics compiled after major downturns show dramatic spikes that overwhelmed charitable relief systems and left many families without consistent access to food or housing.28 These patterns reveal how closely survival was tied to uninterrupted employment in a wage-dependent economy.

The absence of employer-provided benefits compounded this vulnerability. Industrial workers had no access to health insurance, disability compensation, or pensions, meaning that injury, aging, or death produced immediate economic consequences for entire households. When a primary wage earner was disabled or killed, widows and children often entered wage labor themselves or relied on charity to survive. Early social surveys documented how household stability collapsed following workplace injury or death, demonstrating that precarity extended across generations rather than ending with the individual worker.29

Replaceability ultimately shaped workers’ social and political position. Treated as interchangeable components within industrial systems, laborers were valued only so long as they remained productive and compliant. This perception eroded claims to dignity, security, and civic standing, reinforcing power imbalances that favored capital over labor. In this way, economic precarity was not a byproduct of industrialization but a governing principle that sustained industrial growth by keeping workers dependent and constrained.30

Resistance, Reform, and the Limits of Early Labor Movements

Workers did not passively accept the conditions imposed by Gilded Age industrial capitalism. From the earliest decades of large-scale industrialization, laborers organized strikes, formed unions, and participated in collective protests aimed at reducing hours, raising wages, and improving safety. By the 1870s and 1880s, national labor organizations such as the Knights of Labor had attracted hundreds of thousands of members, reflecting widespread dissatisfaction with industrial working conditions.31 These movements articulated a vision of labor dignity that challenged the prevailing assumption that economic efficiency justified human exhaustion.

Strikes became one of the most visible forms of resistance. Railroad workers, miners, and factory laborers repeatedly halted production to demand shorter hours or protest wage cuts. The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which paralyzed transportation networks across multiple states, revealed both the scale of worker unrest and the fragility of industrial order when labor withdrew cooperation.32 Yet such actions also exposed workers to severe retaliation, including blacklisting, eviction from company housing, and permanent exclusion from employment within entire industries.

Employers and the state responded forcefully to labor organizing. Private security forces, local police, state militias, and federal troops were frequently deployed to suppress strikes, often resulting in violence and death. Courts issued injunctions restricting picketing and union activity, framing labor protest as a threat to public order and commerce rather than an exercise of collective rights.33 These interventions reinforced the imbalance of power between capital and labor, signaling that the state would defend property and production even at the expense of worker lives.

Legal and political barriers further constrained reform efforts. Courts routinely interpreted labor laws narrowly, while upholding contractual doctrines that favored employers. Attempts to regulate hours or mandate safety standards faced constitutional challenges under doctrines emphasizing freedom of contract.34 Even modest reforms, such as employer liability laws or factory inspection regimes, were often weakened through exemptions or underfunding, limiting their practical effect on daily working conditions.

Despite these obstacles, reform movements gradually altered public discourse. Journalists, social investigators, and labor advocates documented abuses in factories and mines, framing industrial exploitation as a social problem rather than an individual failure. Organizations campaigning for child labor restrictions, workplace safety, and shorter hours succeeded in raising awareness, even when immediate policy change proved elusive.35 These efforts laid the groundwork for later Progressive Era reforms by shifting moral responsibility toward employers and the state.

The limited success of early labor movements should not be mistaken for failure. While workers rarely achieved lasting victories during the Gilded Age itself, their resistance exposed the contradictions of an economic system that celebrated progress while tolerating suffering. By forcing exploitation into public view, labor activism destabilized claims that industrial capitalism was inherently benevolent. In doing so, workers carved out a political and moral space that would later support more comprehensive labor protections in the twentieth century.36

Conclusion: Industrial Progress and Moral Reckoning

The abuses suffered by the working class during America’s Gilded Age were not aberrations produced by an immature industrial system. They were the logical outcome of an economic order that prioritized output, profit, and expansion over human well-being. Long hours, unsafe workplaces, child labor, immigrant exploitation, deskilling, and economic precarity formed an interlocking structure rather than a series of isolated failures. Contemporary observers understood this connection, warning that unchecked industrial power transformed laborers into expendable resources rather than participants in shared prosperity.37

Industrial capitalism reshaped not only work but the moral assumptions governing responsibility and risk. Employers disclaimed liability for injury, courts reinforced doctrines that favored capital, and the state intervened primarily to preserve order rather than protect workers. The result was a labor system in which suffering was normalized and insecurity institutionalized. Scholars of the period have shown that this framework depended on redefining harm as inevitable and poverty as personal rather than structural, thereby insulating economic growth from ethical scrutiny.38 These assumptions delayed reform by framing exploitation as the cost of progress rather than a problem requiring correction.

Yet resistance and reform efforts, however constrained, altered the historical trajectory of labor relations. Workers, reformers, and investigators forced industrial abuses into public view, undermining claims that prosperity alone justified social inequality. Campaigns against child labor, unsafe conditions, and excessive hours reframed labor exploitation as a collective responsibility, even when immediate victories proved elusive. The persistence of these critiques ensured that industrial labor could no longer be discussed solely in terms of efficiency and output, but had to be measured against human cost.39

The Gilded Age thus stands as both a foundation and a warning. It demonstrates how economic growth can coexist with widespread degradation when labor is treated as infinitely replaceable, and how social stability erodes when insecurity becomes a governing principle. The eventual emergence of labor protections in the twentieth century did not represent a natural evolution of capitalism, but a corrective response to the moral failures of this earlier era. Understanding the abuse of the working class during the Gilded Age is therefore essential not only to interpreting the past, but to recognizing the conditions under which progress loses its claim to legitimacy.40

Appendix

Footnotes

- United States Bureau of Labor, Report on the Statistics of Wages in Manufacturing Industries (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1892).

- David Montgomery, The Fall of the House of Labor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

- Jacob A. Riis, How the Other Half Lives (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890).

- United States Bureau of Labor, Child Labor in the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904).

- United States Bureau of Labor, Report on the Statistics of Wages and Hours of.

- United States Census Office, Twelfth Census of the United States: Occupations (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1900).

- Lawrence B. Glickman, A Living Wage: American Workers and the Making of Consumer Society (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997).

- State of New York, Factory Inspectors’ Report (Albany: State Printing Office, 1899).

- United States Bureau of Labor, Industrial Accidents and Hygiene (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907).

- Morton J. Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law, 1870–1960 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 61–65.

- Crystal Eastman, Work-Accidents and the Law (New York: Charities Publication Committee, 1910).

- United States Census Office, Twelfth Census of the United States.

- United States Bureau of Labor, Child Labor in the United States.

- Lewis W. Hine, Child Labor Photographs, National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress.

- Viviana A. Zelizer, Pricing the Priceless Child (New York: Basic Books, 1985).

- Hugh D. Hindman, Child Labor: An American History (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1905).

- David Nasaw, Children of the City (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

- United States Census Office, Twelfth Census of the United States.

- John R. Commons et al., History of Labour in the United States, vol. 2 (New York: Macmillan, 1918).

- David Montgomery, Workers’ Control in America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979).

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

- Harry Braverman, Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974).

- Montgomery, Workers’ Control in America.

- Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (New York: Macmillan, 1899).

- Alfred D. Chandler Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977).

- Montgomery, The Fall of the House of Labor.

- Christopher L. Tomlins, Law, Labor, and Ideology in the Early American Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- Robert Higgs, The Transformation of the American Economy, 1865–1914 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971).

- Theda Skocpol, Protecting Soldiers and Mothers (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992).

- Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011).

- Leon Fink, Workingmen’s Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983).

- Philip S. Foner, The Great Labor Uprising of 1877 (New York: Monad Press, 1977).

- William Forbath, Law and the Shaping of the American Labor Movement (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991).

- Christopher L. Tomlins, The State and the Unions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

- Robert H. Wiebe, The Search for Order, 1877–1920 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1967).

- David Brody, Labor Embattled: History, Power, Rights (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005).

- Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform (New York: Vintage Books, 1955).

- Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation (Boston: Beacon Press, 1944).

- Daniel T. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Thomas C. Leonard, Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

Bibliography

- Braverman, Harry. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974.

- Brody, David. Labor Embattled: History, Power, Rights. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005.

- Chandler, Alfred D., Jr. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977.

- Commons, John R., et al. History of Labour in the United States. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan, 1918.

- Eastman, Crystal. Work-Accidents and the Law. New York: Charities Publication Committee, 1910.

- Fink, Leon. Workingmen’s Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983.

- Foner, Philip S. The Great Labor Uprising of 1877. New York: Monad Press, 1977.

- Glickman, Lawrence B. A Living Wage: American Workers and the Making of Consumer Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

- Higgs, Robert. The Transformation of the American Economy, 1865–1914. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Hindman, Hugh D. Child Labor: An American History. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1905.

- Hofstadter, Richard. The Age of Reform. New York: Vintage Books, 1955.

- Horwitz, Morton J. The Transformation of American Law, 1870–1960. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Leonard, Thomas C. Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- —-. Workers’ Control in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Nasaw, David. Children of the City. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1944.

- Riis, Jacob A. How the Other Half Lives. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890.

- Rodgers, Daniel T. Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Rosner, David, and Gerald Markowitz. Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the Politics of Occupational Disease in Twentieth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- Skocpol, Theda. Protecting Soldiers and Mothers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Tomlins, Christopher L. Law, Labor, and Ideology in the Early American Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- —-. The State and the Unions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Veblen, Thorstein. The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Macmillan, 1899.

- Wiebe, Robert H. The Search for Order, 1877–1920. New York: Hill and Wang, 1967.

- White, Richard. Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. New York: W.W. Norton, 2011.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.