The survival strategies developed during the Great Depression reveal a society forced to reconstruct daily life under conditions of prolonged economic failure.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Survival as Social Practice

For those hit hardest by the Great Depression, survival was neither passive endurance nor simple withdrawal from economic life. It was an active, adaptive process that reshaped daily behavior, household organization, and community relations. Families did not merely wait for conditions to improve. They altered how they ate, dressed, heated their homes, and interacted with neighbors, developing strategies that blurred the line between necessity and innovation. Contemporary observers noted that survival depended less on formal employment than on the ability to “make do” within collapsing markets, a phrase that captured both ingenuity and constraint.1

The scale of economic dislocation made such adaptation unavoidable. By the early 1930s, mass unemployment and wage collapse stripped millions of households of reliable cash income, rendering participation in a consumer economy impossible for large segments of the population.2 In this context, survival practices such as gardening, bartering, shared housing, and extreme frugality functioned as substitutes for wages rather than supplements. These practices were not marginal or eccentric responses. They became normalized behaviors that defined everyday life for the unemployed and underemployed, particularly in urban working-class neighborhoods and rural areas already operating near subsistence levels.

Survival during the Depression was also deeply social. Families relied on extended kin networks, neighbors, churches, and informal community organizations to pool resources and distribute risk. Social workers and relief administrators repeatedly observed that households which maintained strong local ties were better able to endure prolonged hardship than those isolated by migration or social fragmentation.3 Potlucks, shared meals, and reciprocal labor exchanges transformed scarcity into collective experience, mitigating hunger and loneliness even when material relief remained insufficient.

At the same time, survival strategies exposed profound inequalities. Racial segregation, gendered labor expectations, and geographic disparities shaped who could access assistance and on what terms. Black communities, frequently excluded from public relief or relegated to inferior aid, established parallel systems of support through churches and mutual aid societies.4 Women absorbed disproportionate responsibility for household survival, stretching limited resources through unpaid domestic labor that remained largely invisible in economic statistics. Survival was thus unevenly distributed, reflecting structural inequities rather than individual virtue or failure.

What follows treats survival not as a footnote to economic collapse but as a historical subject in its own right. By examining how households and communities adapted to deprivation, it reveals the lived realities beneath unemployment figures and policy debates. Survival strategies illuminate how ordinary people navigated structural failure through cooperation, improvisation, and sacrifice, while also revealing the limits of resilience in the absence of sufficient institutional support. Understanding survival as social practice allows us to see the Great Depression not only as an economic crisis, but as a transformation in the organization of everyday life.5

Food Security through Self-Provisioning

As wage income collapsed during the Great Depression, food security increasingly depended on households’ ability to shift away from market reliance and toward self-provisioning. Backyard gardens, vacant-lot cultivation, and small community plots became widespread responses to hunger, particularly in urban working-class neighborhoods. Municipal governments and relief agencies often encouraged these efforts, recognizing that homegrown produce reduced demand on strained relief budgets. By the mid-1930s, millions of families were supplementing their diets through gardening, transforming unused land into a critical source of calories and nutritional diversity.6

Gardening functioned not merely as an emergency measure but as a partial return to subsistence practices that industrial capitalism had previously rendered unnecessary for many urban households. Extension services and home economics publications distributed guides on planting, crop rotation, and seasonal preservation, reflecting an institutional acknowledgment that self-provisioning was now essential.7 These materials emphasized vegetables that produced high yields with minimal inputs, such as potatoes, beans, cabbage, and tomatoes, reinforcing a diet oriented toward durability rather than variety. In this sense, gardening represented a structural adaptation to economic collapse rather than a nostalgic revival of preindustrial habits.

Animal husbandry further expanded household food production. Families who could do so raised chickens for eggs and meat, even in densely populated areas where local ordinances technically prohibited livestock. Contemporary observers noted that enforcement of such regulations was often lax, as authorities recognized the necessity of these practices.8 Chickens offered a renewable protein source at relatively low cost, while scraps and garden waste could be repurposed as feed. The presence of backyard animals blurred the distinction between urban and rural survival strategies, illustrating how economic crisis destabilized established patterns of food consumption.

Food preservation was equally critical to self-provisioning. Canning fruits and vegetables allowed families to stretch harvests across seasons, while pickling, drying, and curing minimized spoilage. Women’s labor was central to these processes, as preservation required time, skill, and careful planning. Relief agencies promoted canning programs through demonstrations and shared equipment, recognizing that preservation transformed short-term abundance into long-term security.9 Together, gardening, animal raising, and preservation formed an integrated survival system that reduced dependence on cash income while redefining household labor as a primary defense against hunger.

Eating Poverty: Diet, Ingenuity, and Nutrition

Depression-era diets reflected extreme constraint rather than preference. As cash income disappeared, families reorganized meals around foods that were cheap, filling, and widely available. Beans, rice, cornmeal, potatoes, and bread became dietary staples because they delivered calories at minimal cost and could be prepared in large quantities. Relief agencies explicitly recommended such foods in pamphlets and meal plans, emphasizing satiety and affordability over taste or variety.10 These recommendations shaped daily eating habits across both urban and rural households.

Protein consumption declined sharply, forcing families to stretch limited meat supplies as far as possible. When animals were slaughtered, households used every edible part, including organs, bones, and fat, which were transformed into soups, stews, gravies, and broths. Contemporary home economics manuals advised that bones be boiled repeatedly to extract remaining nutrients, reflecting both nutritional awareness and economic necessity.11 This approach blurred the boundary between waste and sustenance, redefining thrift as survival rather than virtue.

Soup emerged as a central feature of Depression cooking because it allowed small quantities of ingredients to feed many people. Large pots simmered for hours, combining vegetables, scraps of meat, and grains into meals that could be reheated and extended across multiple days. Social workers and relief administrators noted that soup kitchens adopted similar strategies, relying on bulk cooking to maximize limited supplies.12 At the household level, soup functioned as both nourishment and strategy, transforming scarcity into continuity.

Malnutrition nevertheless remained a persistent threat. Public health studies from the 1930s documented deficiencies in vitamins and protein, particularly among children and the elderly. Milk, fresh fruit, and meat were often beyond reach, leading to diets that filled stomachs without meeting nutritional needs.13 Families attempted to compensate through gardens and preservation, but these measures could not fully offset the structural effects of poverty. Eating poverty thus involved constant negotiation between hunger avoidance and nutritional adequacy.

Despite deprivation, Depression-era diets demonstrated remarkable ingenuity. Recipes circulated informally among neighbors, churches, and women’s groups, sharing methods for substituting ingredients and reusing leftovers. This culinary knowledge formed part of a broader survival culture in which food preparation became an adaptive skill rather than a routine task. By reshaping meals around endurance rather than enjoyment, households turned eating into a disciplined response to economic collapse, revealing how nutrition became inseparable from survival strategy during the Great Depression.14

Clothing, Repair, and the Culture of Reuse

As incomes vanished, clothing shifted from a consumer good to a long-term household asset that required constant maintenance. Families extended the life of garments through patching, darning, and careful laundering, practices that had declined during the consumer boom of the 1920s but returned out of necessity. Women’s magazines and home economics manuals emphasized mending as an essential domestic skill, offering detailed instructions for repairing worn seams, reinforcing elbows, and re-soling shoes.15 Clothing durability became a measure of household competence rather than fashion awareness.

Material scarcity also encouraged the repurposing of unconventional textiles. Flour and feed sacks, distributed widely through agricultural supply chains, were transformed into dresses, shirts, underwear, and children’s clothing. Manufacturers responded by printing sacks with decorative patterns, implicitly acknowledging their secondary use. Social surveys and personal accounts reveal that sack clothing carried a complex social meaning, simultaneously signaling poverty and ingenuity, especially in rural and small-town communities.16 The widespread adoption of sack garments illustrates how industrial packaging entered domestic survival economies in unexpected ways.

Sharing further reduced the need for new clothing. Families rotated garments among siblings, passed clothing between relatives, and borrowed special-occasion items such as coats or dresses. In some communities, a single formal dress might circulate among multiple women for church or social events. These practices reshaped norms of ownership and privacy, turning clothing into a communal resource rather than an individual possession.17 Such arrangements reflected both economic pressure and the persistence of social obligations despite material deprivation.

The labor required to sustain clothing supplies fell overwhelmingly on women, whose unpaid work absorbed the costs of scarcity. Repair and reuse demanded time, skill, and patience, often performed late at night after other household responsibilities were met. Scholars have noted that this invisible labor cushioned families from destitution while obscuring the true extent of economic hardship.18 Clothing survival strategies thus reveal how deprivation was managed through domestic effort, transforming scarcity into routine labor rather than public crisis.

Heat, Light, and Energy Survival

Maintaining heat and light became a daily struggle as household incomes collapsed and fuel costs consumed an ever larger share of limited resources. Families reduced heating to a single room, often the kitchen, and relied on heavy clothing and shared blankets to endure winter cold. Contemporary social surveys reported that many households deliberately allowed temperatures to drop at night, accepting discomfort as a trade-off for conserving coal or wood.19 These practices reveal how survival required the reorganization of domestic space around energy scarcity.

Fuel acquisition itself became an improvisational activity. Urban families scavenged for scrap wood, discarded crates, and fallen branches, while rural households relied more heavily on wood-burning stoves. Coal, when available, was rationed carefully, with households burning low fires rather than allowing stoves to go out completely. Municipal authorities were aware of widespread fuel scavenging and often tolerated it, recognizing that strict enforcement would have exacerbated suffering during extreme weather.20 Energy survival thus operated in a gray zone between legality and necessity.

Electricity, where it existed, was used sparingly. Families limited lighting to a single bulb and avoided electrical appliances entirely. In some neighborhoods, particularly in urban tenements, households illegally tapped into nearby lines or shared electricity with neighbors to reduce costs. Utility companies lodged complaints about theft, but enforcement proved inconsistent as public sympathy often favored struggling families over corporate providers.21 Such practices underscore how survival strategies sometimes involved quiet resistance to market discipline rather than compliance with it.

The consequences of energy deprivation extended beyond physical discomfort. Poor heating contributed to illness, particularly respiratory infections, while dim lighting limited evening activities such as reading or sewing. Families responded by going to bed early to conserve fuel and calories, effectively compressing daily life into daylight hours.22 These adjustments transformed energy scarcity into a structuring force within household routines, demonstrating how survival during the Great Depression reshaped not only consumption but the rhythm of everyday life.

Barter Economies and Informal Exchange

As cash disappeared from daily circulation, barter emerged as a practical substitute rather than a symbolic rejection of money. Families exchanged goods and services directly, trading food, clothing repair, child care, and manual labor for necessities they could not otherwise afford. Sociological field studies from the early 1930s documented neighborhoods where barter functioned as a parallel economy, sustained by trust and repeated interaction rather than formal contracts.23 These exchanges allowed households to meet basic needs even when wages and relief payments proved insufficient.

Skills became a form of currency within these informal systems. Men with mechanical knowledge repaired tools, stoves, or automobiles in exchange for food or fuel, while women traded sewing, laundering, or cooking services. Such arrangements depended on mutual recognition of value rather than standardized prices, reflecting a flexible economic logic adapted to scarcity.24 Barter thus transformed personal ability into economic capital, enabling survival through contribution rather than possession.

Agricultural communities relied heavily on barter, particularly where cash crop prices collapsed. Farmers exchanged produce, eggs, and meat for labor or manufactured goods, often bypassing formal markets altogether. In some regions, local merchants accepted goods or labor in lieu of payment, acknowledging that rigid insistence on cash would have driven customers away permanently.25 These practices highlight how barter blurred boundaries between household, community, and market economies during the Depression.

Urban barter networks developed different characteristics. Tenement neighborhoods supported dense webs of exchange shaped by proximity and shared hardship. Families borrowed tools, shared meals, and pooled fuel supplies, expecting that assistance would be returned when circumstances allowed. Social workers observed that these reciprocal systems often proved more reliable than formal relief, particularly when bureaucratic delays interrupted aid.26 Barter in cities thus functioned as both economic adaptation and social glue.

Informal exchange was not without limits. Barter required surplus, skills, or social connections, leaving the most isolated households at a disadvantage. Migrant workers, recent arrivals, and those without marketable skills struggled to participate fully in reciprocal economies.27 These exclusions reveal that barter, while adaptive, could not fully replace cash income or institutional support, reinforcing existing inequalities even as it mitigated hardship for others.

Nevertheless, barter economies reveal how survival during the Great Depression depended on cooperation rather than individual self-sufficiency. By reorganizing exchange around relationships rather than money, communities temporarily redefined economic value. These systems did not overturn capitalism, but they sustained life during its collapse, illustrating how informal exchange operated as a survival mechanism embedded within social bonds rather than abstract markets.28

Community Solidarity and Shared Survival

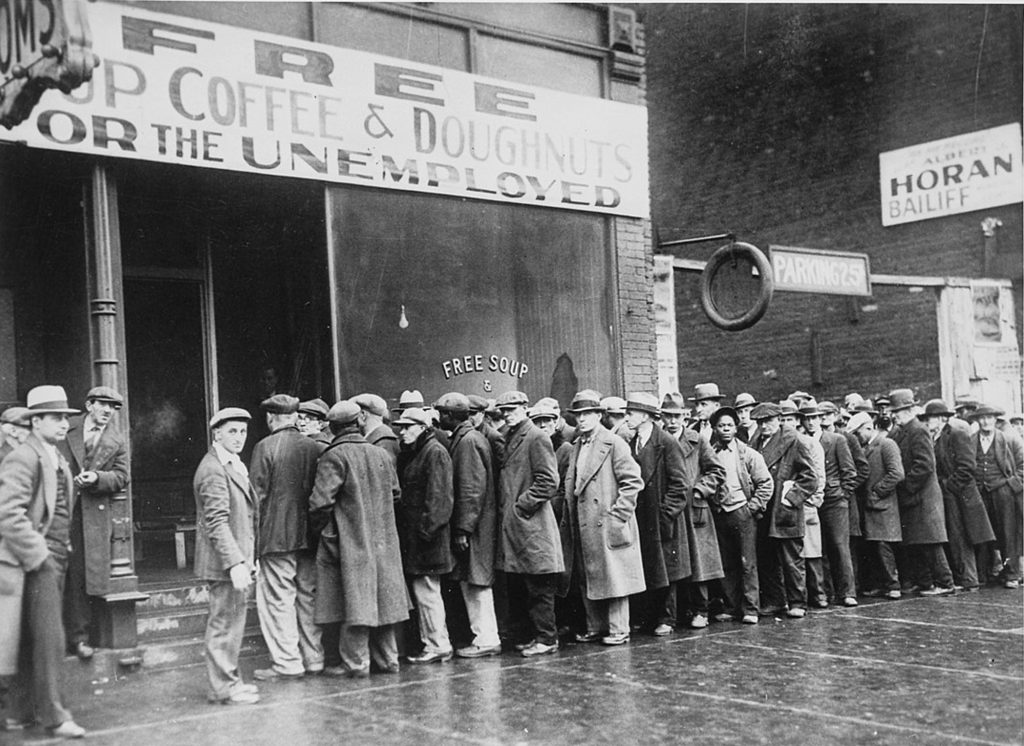

As private resources dwindled, community institutions became central to survival during the Great Depression. Churches, neighborhood associations, and fraternal organizations organized shared meals, clothing drives, and informal relief efforts that supplemented or replaced inadequate public aid. Clergy and lay leaders coordinated potlucks and communal dinners that allowed families to eat without stigma, reframing assistance as fellowship rather than charity. Contemporary observers noted that these gatherings provided both nourishment and a sense of normalcy amid prolonged uncertainty.29

Churches in particular functioned as logistical hubs for survival. Beyond food distribution, congregations organized fuel sharing, child care, and temporary shelter for families facing eviction. Ministers often acted as intermediaries between households and relief agencies, helping navigate bureaucratic processes that many found intimidating or inaccessible.30 These roles extended religious institutions beyond spiritual care into practical governance at the local level, reinforcing their importance in sustaining communities under stress.

Mutual aid also operated at the neighborhood scale. Informal groups coordinated shared cooking, rotating child supervision, and pooled purchases of staple foods to reduce costs. In some areas, neighbors collectively prepared meals in a single home to conserve fuel and labor, distributing portions afterward. Social workers reported that such arrangements emerged organically, driven by proximity and shared hardship rather than formal organization.31 These practices illustrate how survival strategies were embedded in everyday social relations.

Community solidarity was not limited to material assistance. Shared entertainment, including music, storytelling, and informal gatherings, offered psychological relief when commercial leisure became unaffordable. Churches and community centers hosted low-cost or free events that replaced movies and paid amusements, preserving social life despite austerity.32 Such activities mitigated isolation and despair, demonstrating that emotional sustenance was as vital as food and shelter.

Yet community-based survival had limits. Reliance on local networks could strain relationships over time, particularly when hardship persisted for years rather than months. Disagreements over contribution and need sometimes generated tension, and households lacking strong social ties faced exclusion.33 Even so, communal survival efforts remained a defining feature of Depression life, revealing how cooperation functioned as a practical response to structural failure when both markets and the state fell short.

Crowded Homes and Extended Families

As incomes collapsed and evictions mounted, households responded by consolidating living arrangements. Families doubled up with relatives, adult children returned to parental homes, and extended kin networks pooled housing resources to avoid homelessness. Census data and housing surveys from the 1930s show a marked increase in multi-family and multi-generational households, particularly in urban working-class districts.34 These arrangements reduced rent burdens and allowed families to share food, fuel, and childcare responsibilities, transforming private homes into collective survival spaces.

Household crowding altered family dynamics and domestic routines. Privacy diminished as bedrooms were shared and common spaces repurposed for sleeping, cooking, and work. Social workers noted that overcrowding increased stress and conflict, yet it also facilitated cooperation, as labor and resources were redistributed within the household.35 Grandparents contributed childcare, older children sought informal work, and adults coordinated schedules to manage scarce resources efficiently. Survival thus depended on negotiation as much as solidarity.

Rural families relied heavily on extended households as well, particularly when farm income collapsed or tenants were displaced. Relatives took in displaced farmers, and households expanded to include siblings, cousins, and in-laws who could contribute labor even when cash was scarce. Agricultural surveys emphasized that these arrangements allowed families to remain on the land when individual households would otherwise have failed.36 Crowding in this context functioned as an economic strategy rather than a temporary inconvenience.

Despite its benefits, household consolidation had limits. Overcrowding strained sanitation, increased the spread of illness, and intensified emotional pressures, especially during prolonged unemployment. Families without access to extended kin networks faced greater vulnerability, highlighting how survival strategies were unevenly distributed along lines of family structure and social capital.37 Crowded homes thus reveal both the resilience and fragility of familial survival mechanisms during the Great Depression.

Racial Exclusion and Black Community Self-Help

For Black Americans, survival during the Great Depression was shaped not only by economic collapse but by entrenched racial exclusion. Public relief programs, when available, were frequently segregated, administered discriminatorily, or denied altogether. Local relief boards often prioritized white applicants, and Black families were routinely offered lower-quality aid or fewer work opportunities. Contemporary investigations and Black newspapers documented widespread disparities in relief distribution, underscoring how racism compounded economic hardship.38

In response, Black communities mobilized their own survival networks. Churches served as the primary institutional backbone, organizing soup kitchens, clothing drives, and temporary shelters when public facilities were inaccessible. Ministers and lay leaders coordinated relief efforts that drew on congregational donations and volunteer labor. These initiatives reflected a long tradition of mutual aid within Black communities, intensified by the failures of public assistance during the Depression.39 Survival thus depended heavily on internal community organization rather than state intervention.

Black women played a central role in sustaining these efforts. They organized food preparation, managed aid distribution, and extended informal care to families in crisis. Many women also relied on domestic work, laundering, and cooking for white households, even as those opportunities declined during the Depression. Social surveys noted that Black women’s labor functioned as a stabilizing force within families and neighborhoods, absorbing economic shocks through unpaid and underpaid work.40

Federal relief programs offered limited opportunities but reproduced existing inequalities. New Deal agencies such as the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps employed Black workers, yet segregation and discrimination remained pervasive. Black participants were often assigned the lowest-paying jobs or excluded from skilled positions, while relief administrators deferred to local racial norms.41 These patterns reveal how federal intervention mitigated hardship without dismantling structural racism.

Despite these constraints, Black community self-help efforts sustained life and dignity under conditions of exclusion. Mutual aid, church-centered relief, and informal economies compensated for discriminatory systems while reinforcing collective identity. However, these strategies also carried heavy burdens, as communities were forced to solve problems created by systemic injustice. Survival in Black America during the Great Depression thus exposes the limits of resilience when inequality is built into the very institutions meant to provide relief.42

Federal Relief and the Limits of the New Deal

Federal intervention marked a significant departure from earlier approaches to economic crisis, yet it did not eliminate the need for household survival strategies. Programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) provided paid employment to millions, offering wages that stabilized families and restored a measure of dignity through work. Participants built roads, schools, parks, and public buildings, leaving a visible imprint on the American landscape.43 However, these programs reached only a portion of those in need, and wages were often insufficient to support entire households without supplementary strategies.

The CCC targeted young, unmarried men, removing them from family households while sending a portion of their earnings home. This structure alleviated some domestic pressure but excluded women and older men entirely. Scholars have noted that the program reinforced gendered assumptions about breadwinning while failing to address the needs of families without eligible male members.44 Survival for those excluded from work programs continued to rely heavily on informal economies, family consolidation, and community aid.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) sought to stabilize farm income by paying producers to limit output, raising crop prices and reducing surpluses. While this policy benefited many landowning farmers, it often harmed tenant farmers and sharecroppers, who were displaced when land was taken out of production. Contemporary reports documented widespread evictions in the rural South, forcing displaced families to migrate or rely on emergency relief.45 Federal agricultural policy thus mitigated economic collapse for some while intensifying insecurity for others.

Direct relief programs such as the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) provided cash and material assistance to the unemployed, marking a significant expansion of federal responsibility for welfare. FERA funds supported food distribution, clothing aid, and temporary shelter, offering immediate relief from hunger and exposure.46 Yet relief levels varied widely by locality, as federal funds were administered through state and local agencies that imposed their own eligibility criteria and priorities. This decentralization produced uneven outcomes that reflected regional inequalities rather than uniform national standards.

The Farm Security Administration (FSA) addressed rural poverty through loans, resettlement projects, and cooperative farming initiatives. Its programs aimed to rehabilitate families rather than merely sustain them, emphasizing long-term stability through land access and credit.47 Despite innovative approaches, the FSA reached a limited population and faced political resistance from those who viewed its efforts as excessive federal intrusion. For many rural poor, FSA assistance supplemented rather than replaced traditional survival strategies.

New Deal relief programs alleviated suffering without resolving structural vulnerability. They reduced hunger, provided employment, and stabilized communities, yet they did not eliminate reliance on gardens, barter, shared housing, and extreme frugality. The persistence of survival practices throughout the 1930s reveals that federal relief functioned as a partial scaffold rather than a comprehensive solution. New Deal intervention expanded the boundaries of state responsibility, but it did not fundamentally displace the social and household mechanisms that sustained life during the Great Depression.48

Cutting Pleasure and Conserving Life

As economic insecurity persisted, families eliminated nonessential spending with a severity that reshaped daily life. Paid entertainment such as movies, dances, and sporting events disappeared from many household budgets, even though these activities had previously offered inexpensive respite. Social surveys from the early 1930s recorded sharp declines in attendance at theaters and amusement venues, particularly among unemployed workers.49 Leisure was not merely postponed. It was redefined as an unaffordable luxury incompatible with survival.

Conserving resources extended beyond money to energy and physical endurance. Families reduced activity to minimize fuel use and food consumption, sometimes remaining in bed for extended periods during cold weather to conserve heat and calories. Contemporary observers described households organizing daily routines around daylight hours, avoiding nighttime activity altogether to reduce lighting and heating costs.50 These strategies reveal how survival compressed life into its most basic rhythms, subordinating comfort to necessity.

The psychological toll of austerity was profound. Eliminating small pleasures intensified feelings of isolation, boredom, and despair, particularly as hardship stretched from months into years. Diaries and oral histories reveal a persistent tension between resignation and quiet endurance, as families struggled to maintain morale without customary outlets for relief.51 In this context, emotional survival required as much adaptation as physical sustenance, even when material deprivation took precedence.

Restraint itself became a learned discipline. Families developed habits of vigilance and self-denial that persisted beyond the worst years of the Depression, shaping attitudes toward consumption for decades. Scholars have noted that Depression survivors often carried frugality into later life, viewing waste as morally suspect even during periods of abundance.52 Cutting pleasure thus functioned not only as a survival tactic but as a lasting cultural transformation rooted in prolonged insecurity.

Hoovervilles and Makeshift Shelter

As evictions and foreclosures accelerated, makeshift settlements emerged on the margins of American cities. These shantytowns, commonly labeled “Hoovervilles,” were constructed from scavenged materials such as scrap wood, tin, cardboard, and tar paper. Municipal surveys and contemporary journalism documented their rapid spread near rail yards, riverbanks, and unused land, where displaced families sought shelter beyond the reach of rent and utilities.53 Hoovervilles represented a last line of defense against homelessness when both markets and relief systems failed.

Life within these settlements was marked by extreme vulnerability but also by improvised order. Residents organized dwellings into informal streets, established rules governing space and conduct, and pooled labor to improve shelter stability. Observers noted the presence of shared cooking areas and communal fire pits, reflecting collective strategies to conserve fuel and resources.54 These practices reveal that Hoovervilles were not merely chaotic encampments but adaptive communities shaped by necessity and mutual dependence.

Public responses to Hoovervilles varied widely. Some local governments tolerated or quietly assisted settlements during periods of severe need, while others dismantled them through police action, citing sanitation and safety concerns. Relief agencies often struggled to address Hooverville populations, whose transient status complicated eligibility and oversight.55 The uneven treatment of these communities underscores how survival outside formal housing exposed residents to arbitrary authority as well as environmental hardship.

Hoovervilles ultimately embodied both desperation and resilience. They made visible the human consequences of mass unemployment, challenging narratives that framed the Depression as a temporary or abstract economic problem. At the same time, the persistence of these settlements demonstrated how displaced individuals reassembled social life under conditions of extreme scarcity. Makeshift shelter became a spatial expression of survival, revealing how people adapted when conventional housing ceased to be attainable.56

Learning to Survive: Skills, Adaptation, and Resilience

The prolonged nature of the Great Depression forced households to move beyond short-term improvisation toward the systematic acquisition of survival skills. Families learned to repair tools, furniture, and household goods rather than replace them, often relying on trial, error, and shared knowledge rather than formal training. Contemporary accounts describe adults and children alike learning skills once outsourced to markets, such as shoe repair, basic carpentry, and mechanical maintenance.57 Survival thus became cumulative, with each learned skill reducing future vulnerability.

Food-related skills expanded alongside material repair. Women and men refined techniques for stretching ingredients, preserving seasonal abundance, and preparing nutritionally adequate meals from limited resources. Community demonstrations and relief-sponsored classes taught canning, bread baking, and economical cooking, formalizing what many households were already practicing informally.58 These skills transformed scarcity into routine, embedding survival knowledge within daily life rather than treating it as an emergency response.

Adaptation also required learning how to navigate institutions. Relief applicants mastered the language and procedures of aid agencies, understanding how to document need, appeal decisions, and comply with shifting eligibility rules. Social workers observed that experienced applicants often fared better than first-time petitioners, not because their need was greater, but because they understood bureaucratic expectations.59 Survival, in this sense, depended as much on administrative literacy as on material ingenuity.

Children absorbed survival skills through participation rather than instruction. They learned thrift, restraint, and resourcefulness by observing adult behavior and contributing labor within the household. Oral histories suggest that these lessons shaped lifelong attitudes toward work, consumption, and security, reinforcing habits of caution long after economic conditions improved.60 The transmission of survival knowledge across generations reveals how the Depression functioned as a formative social experience rather than a temporary disruption.

Resilience, however, should not be romanticized. The skills developed under economic duress often emerged from necessity rather than choice, and their acquisition carried emotional and physical costs. Continuous adaptation demanded vigilance, discipline, and sacrifice, leaving little space for rest or aspiration. Scholars caution that resilience narratives can obscure the structural conditions that made such adaptation necessary in the first place.61 Learning to survive did not imply thriving. It meant enduring within sharply constrained possibilities.

The legacy of Depression-era adaptation endured. The skills, habits, and social practices developed during the 1930s reshaped postwar attitudes toward consumption, waste, and security. Survivors carried forward an ethic of preparedness rooted in lived experience rather than ideology.62 Learning to survive thus stands as both a testament to human adaptability and a reminder of the profound costs imposed when economic systems fail to provide basic stability.

Conclusion: Survival, Memory, and Historical Meaning

The survival strategies developed during the Great Depression reveal a society forced to reconstruct daily life under conditions of prolonged economic failure. Gardening, bartering, shared housing, and extreme frugality were not marginal behaviors but central practices that sustained millions when wages, markets, and formal relief proved inadequate. These strategies demonstrate that survival was an active social process shaped by cooperation, improvisation, and sacrifice rather than passive endurance. Contemporary observers recognized that survival depended less on individual resilience than on access to family networks, community institutions, and informal economies.63

At the same time, survival practices expose the limits of adaptability. Households could stretch food, repair clothing, and conserve fuel, but these efforts came at significant physical and emotional cost. Prolonged austerity eroded health, strained relationships, and narrowed future possibilities, particularly for children whose development unfolded within scarcity. Scholars have emphasized that such adaptations should not be mistaken for evidence that deprivation was manageable or benign.64 Survival strategies mitigated suffering, but they did not resolve the structural conditions that produced it.

The uneven distribution of survival options further underscores the role of inequality. Racial exclusion, gendered labor expectations, and geographic disparities shaped who could rely on community support and who remained exposed to extreme vulnerability. Black communities, forced to compensate for discriminatory relief systems, carried disproportionate burdens through self-help and mutual aid. These disparities reveal how survival itself became stratified, reflecting broader patterns of power and exclusion within American society.65

Understanding how the hardest-hit Americans survived the Great Depression therefore enriches our interpretation of the era. It shifts attention away from policy alone and toward the lived realities of households navigating collapse with limited support. Survival strategies illuminate both human ingenuity and systemic failure, reminding us that adaptation is not a substitute for justice. The memory of Depression survival endures not as a story of triumph, but as a warning about the costs borne when economic security is withdrawn from everyday life.66

Appendix

Footnotes

- Studs Terkel, Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (New York: Pantheon Books, 1970).

- David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

- Robert S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd, Middletown in Transition (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1937).

- Harvard Sitkoff, A New Deal for Blacks: The Emergence of Civil Rights as a National Issue (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978).

- Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- Megan J. Elias, Stir It Up: Home Economics in American Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008).

- United States Department of Agriculture, Family Food Production and Conservation (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1933).

- Terkel, Hard Times.

- Amy Bentley, Eating for Victory: Food Rationing and the Politics of Domesticity (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998).

- United States Department of Agriculture, Diets at Four Levels of Nutrition Content and Cost (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1933).

- Elias, Stir It Up.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Feeding the Unemployed (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1934).

- John D. Black, Food Enough (Lancaster: The Jacques Cattell Press, 1943).

- Terkel, Hard Times.

- Susan Strasser, Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1999).

- Katherine Jellison, Entitled to Power: Farm Women and Technology, 1913–1963 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993).

- Lynd and Lynd, Middletown in Transition.

- Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982).

- Lynd and Lynd, Middletown in Transition.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Relief Problems in Urban Areas (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935).

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear.

- Terkel, Hard Times.

- Lynd and Lynd, Middletown in Transition.

- Caroline Ware, Greenwich Village, 1920–1930 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1935).

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Family Relief and Community Cooperation (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1934).

- William Tuttle, Daddy’s Gone to War: The Second World War in the Lives of America’s Children (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

- Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation (Boston: Beacon Press, 1944).

- Lynd and Lynd, Middletown in Transition.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Community Organization and Relief (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935).

- Ware, Greenwich Village, 1920–1930.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear.

- Terkel, Hard Times.

- United States Census Bureau, Fifteenth Census of the United States: Population (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1930).

- Lynd and Lynd, Middletown in Transition.

- Pete Daniel, Breaking the Land: The Transformation of Cotton, Tobacco, and Rice Cultures since 1880 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985).

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear.

- Sitkoff, A New Deal for Blacks.

- Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

- Tera W. Hunter, To ’Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

- Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005).

- Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, Or Does It Explode? Black Harlem in the Great Depression (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

- Jason Scott Smith, Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933–1956 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

- Neil M. Maher, Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- Pete Daniel, Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013).

- William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932–1940 (New York: Harper & Row, 1963).

- Paul K. Conkin, Tomorrow a New World: The New Deal Community Program (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1959).

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear.

- Lynd and Lynd, Middletown in Transition.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Household Economy under Relief Conditions (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1934).

- Terkel, Hard Times.

- Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (New York: Knopf, 2003).

- Kenneth J. Bindas, Remembering the Great Depression in the Rural South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007).

- Todd DePastino, Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Problems of Transient and Homeless Populations (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935).

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear.

- Terkel, Hard Times.

- Elias, Stir It Up.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Relief Administration and Family Adjustment (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935).

- David Nasaw, Children of the City (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

- James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1941).

- Cohen, A Consumers’ Republic.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear.

- Cohen, Making a New Deal.

- Greenberg, Or Does It Explode?

- Terkel, Hard Times.

Bibliography

- Agee, James, and Walker Evans. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1941.

- Bentley, Amy. Eating for Victory: Food Rationing and the Politics of Domesticity. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

- Bindas, Kenneth J. Remembering the Great Depression in the Rural South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

- Black, John D. Food Enough. Lancaster: The Jacques Cattell Press, 1943.

- Cohen, Lizabeth. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- ———. A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. New York: Knopf, 2003.

- Conkin, Paul K. Tomorrow a New World: The New Deal Community Program. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1959.

- Daniel, Pete. Breaking the Land: The Transformation of Cotton, Tobacco, and Rice Cultures since 1880. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985.

- ———. Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- DePastino, Todd. Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Elias, Megan J. Stir It Up: Home Economics in American Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration. Family Relief and Community Cooperation. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1934.

- ———. Household Economy under Relief Conditions. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1934.

- ———. Relief Administration and Family Adjustment. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935.

- ———. Community Organization and Relief. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935.

- ———. Problems of Transient and Homeless Populations. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935.

- ———. Relief Problems in Urban Areas. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935.

- Greenberg, Cheryl Lynn. Or Does It Explode? Black Harlem in the Great Depression. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Hunter, Tera W. To ’Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Katznelson, Ira. When Affirmative Action Was White. New York: W.W. Norton, 2005.

- Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932–1940. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

- Lynd, Robert S., and Helen Merrell Lynd. Middletown in Transition. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1937.

- Maher, Neil M. Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Nasaw, David. Children of the City. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1944.

- Sitkoff, Harvard. A New Deal for Blacks: The Emergence of Civil Rights as a National Issue. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Smith, Jason Scott. Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933–1956. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Strasser, Susan. Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1999.

- Terkel, Studs. Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression. New York: Pantheon Books, 1970.

- Tuttle, William. Daddy’s Gone to War: The Second World War in the Lives of America’s Children. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- United States Census Bureau. Fifteenth Census of the United States: Population. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1930.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Diets at Four Levels of Nutrition Content and Cost. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1933.

- ———. Family Food Production and Conservation. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1933.

- Ware, Caroline. Greenwich Village, 1920–1930. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1935.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.