Across more than two centuries of American history, efforts to criminalize or punish ideological dissent have followed a remarkably consistent logic.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Dissent as a Recurrent American Problem

From its earliest moments, the United States has struggled to reconcile its self-image as a republic founded on liberty with a persistent fear of internal opposition. Political dissent has rarely been treated as a neutral or even healthy feature of democratic life. Instead, it has often been framed as a threat to social order, national survival, or moral cohesion, especially when governing elites believed unity mattered more than argument. That recurring anxiety is not an accident of a few bad moments. It is one of the republic’s durable reflexes, reappearing whenever power feels exposed.

The founding generation articulated expansive principles of free expression, yet it also inherited English legal traditions that treated dissent as potentially seditious. Colonial governance had long operated in a legal culture where attacks on authority could be punished as seditious libel, even when the challenged statements were true.1 Early American political thought drew a distinction between acceptable disagreement and dangerous opposition, a boundary that shifted according to circumstance and control. Revolutionary leaders defended resistance to British authority while suppressing Loyalist speech and participation through loyalty tests, confiscations, and exclusion from civic life, practices that reveal how quickly ideological tolerance narrowed once dissent was redefined as disloyalty.2

This pattern did not end with independence. Across U.S. history, efforts to criminalize or punish ideological dissent have tended to surge during periods of perceived existential threat. Foreign war and geopolitical rivalry repeatedly encouraged lawmakers and executives to treat dissident belief as a kind of internal sabotage rather than protected expression.3 The machinery of repression has not been limited to criminal statutes. It has also taken administrative form through loyalty programs, professional sanctions, immigration enforcement, and surveillance, with the sharpest pressure often falling on movements seen as capable of reorganizing society rather than merely criticizing policy.

The argument of what follows is that the criminalization of ideological dissent is not an aberration in American history but a recurring feature of it. Constitutional protections for speech expanded unevenly over time, yet they never eliminated the impulse to equate dissent with disloyalty, nor did they prevent older tools from returning in new guises. Episodes of repression have tended to leave behind legal precedents and institutional habits that outlast the crisis that rationalized them, making later crackdowns easier to justify and faster to implement. Understanding that continuity matters not only for judging past injustices but for recognizing how readily the language of unity and security can be mobilized against political belief itself.

Revolutionary Origins and the First Loyalty Regimes

The American Revolution was not only a revolt against imperial authority but also an internal struggle over political allegiance. From the earliest stages of resistance, revolutionary leaders confronted the problem of Loyalism, a category that blurred ideological disagreement with civic betrayal. Colonial society fractured along lines of loyalty, neutrality, and resistance, and revolutionary legitimacy increasingly depended on the ability to distinguish friends from enemies within. Local committees of safety and correspondence emerged as central instruments in this process, monitoring speech, enforcing boycotts, and investigating suspected opponents of the revolutionary cause, often operating with quasi-judicial authority outside formal legal systems.4 These bodies transformed dissent from a matter of opinion into a condition subject to public scrutiny and punishment.

Formal law soon reinforced this climate of political surveillance. Revolutionary governments required oaths of allegiance as prerequisites for voting, holding office, practicing certain professions, or even remaining within a community. Refusal to swear loyalty frequently resulted in civil disabilities, imprisonment, or banishment, while state legislatures passed confiscation acts authorizing the seizure of Loyalist property on the grounds of political disaffection rather than criminal conduct.5 Such measures did not merely punish collaboration with Britain. They treated belief itself as actionable, redefining neutrality as a form of opposition and collapsing the distinction between ideological dissent and treason.

These practices drew heavily on inherited English legal assumptions about political order. Colonial law had long criminalized seditious speech, particularly criticism that undermined authority or encouraged disobedience, and revolutionary leaders selectively repurposed those doctrines to defend the new political project. The language of republican virtue emphasized unity, sacrifice, and moral commitment to the common good, leaving little conceptual space for principled dissent once independence was framed as a matter of collective survival.6 Opposition was recast not as disagreement among citizens but as a danger to the revolutionary community itself, allowing repression to coexist with expansive rhetoric about liberty.

The consequences of this first American loyalty regime were substantial and enduring. Tens of thousands of Loyalists fled or were expelled from the newly independent states, reshaping population patterns and property ownership while entrenching the association between dissent and disloyalty in American political culture. More significantly, the Revolution established an enduring precedent: that ideological dissent could be punished during moments of existential crisis without discrediting the legitimacy of the constitutional order being built. The early republic thus inherited not only a language of rights but a practical tradition of loyalty enforcement that would reemerge whenever dissent was again framed as incompatible with national survival.7

The Early Republic and the Sedition Question

The transition from revolutionary struggle to constitutional governance did not resolve American anxieties about dissent. Instead, the early republic inherited a fragile political order marked by partisan rivalry, foreign entanglements, and deep uncertainty about the durability of republican government. Federalists and Democratic-Republicans alike viewed ideological opposition not simply as disagreement but as a potential pathway to factional collapse. In this environment, dissent was increasingly interpreted through the lens of loyalty, with critics of the governing party portrayed as threats to national stability rather than participants in legitimate political debate.

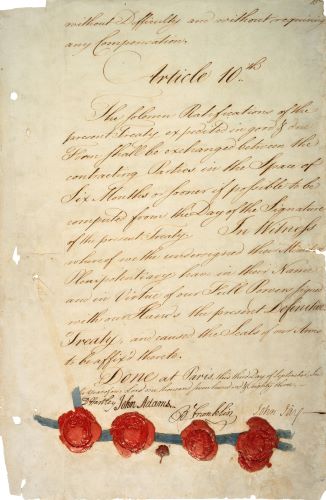

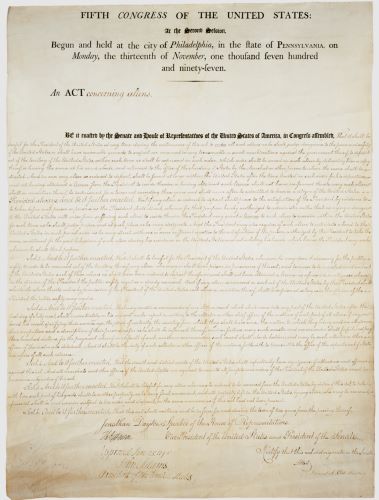

These fears came to a head during the quasi-war with France in the late 1790s. Federalist leaders, convinced that domestic opposition weakened the nation in the face of foreign danger, advanced a suite of laws that dramatically expanded federal authority over speech and political association. The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 criminalized “false, scandalous, and malicious writing” against the federal government, Congress, or the president, language broad enough to encompass much of the partisan press.8 While framed as temporary wartime measures, these statutes embedded the principle that ideological dissent could be treated as a form of internal aggression.

The enforcement of the Sedition Act revealed the law’s fundamentally partisan character. Federal prosecutors targeted editors and writers aligned with the Democratic-Republicans, while Federalist publications faced little scrutiny. Prosecutions focused less on demonstrable harm than on the perceived corrosive effects of criticism itself, especially when directed at executive authority. Judges instructed juries that attacks on government undermined public confidence and social order, reinforcing the idea that dissent was dangerous not because it was false but because it was destabilizing.9 The courtroom became a space where political belief was evaluated as a matter of criminal intent.

Opposition to the Sedition Act did not rest primarily on abstract commitments to free expression. Instead, critics argued that the law violated the constitutional balance of power by arrogating authority not granted to the federal government. James Madison and Thomas Jefferson articulated this position most forcefully in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, asserting that the Constitution did not empower Congress to police political opinion.10 Their argument reframed dissent as a constitutional necessity rather than a social threat, but it did not deny that certain forms of opposition might still warrant suppression at the state level.

The repeal of the Sedition Act and the electoral defeat of the Federalists in 1800 are often cited as evidence of early American commitment to free speech. Yet the episode left lasting marks on American political culture. No court formally invalidated the Sedition Act, and many of those convicted were never fully exonerated. More importantly, the crisis normalized the idea that national security could justify restrictions on political expression, even in peacetime republics founded on popular sovereignty.11 The absence of a decisive constitutional reckoning allowed the logic of repression to remain available for future use.

The Sedition crisis thus established a durable pattern. Ideological dissent was tolerated when it aligned with the dominant political coalition and criminalized when it appeared to threaten the legitimacy of governing authority. The early republic did not resolve the tension between liberty and loyalty. It institutionalized it, leaving behind unresolved questions about who would decide when dissent crossed the line into danger, and under what conditions political belief itself could become a punishable offense.12

Slavery, Abolitionism, and the Criminalization of Moral Opposition

By the early nineteenth century, slavery had become the most volatile fault line in American political life, and abolitionist dissent posed a distinct challenge to prevailing legal and social orders. Unlike earlier partisan conflicts, abolitionism did not merely contest policy or party control. It questioned the moral legitimacy of an entire economic system and the constitutional compromises that sustained it. Southern lawmakers and many Northern allies responded by redefining abolitionist speech as a threat to public order, social stability, and sectional peace, framing moral opposition as a form of agitation rather than protected expression. This reframing allowed dissent to be policed without directly repudiating republican ideals.

Congressional suppression provided an early and visible example. Beginning in the 1830s, the House of Representatives adopted a series of gag rules that automatically tabled petitions related to slavery without discussion, effectively nullifying a long-recognized right of petition. These measures were justified as procedural safeguards against sectional discord, yet they functioned as content-based restrictions aimed specifically at silencing abolitionist appeals. John Quincy Adams’s prolonged campaign against the gag rule exposed its constitutional implications, demonstrating how fears of ideological contagion could override even basic participatory rights.13 The episode underscored the willingness of federal institutions to restrict dissent when moral critique threatened entrenched power.

At the state level, repression was often more direct and violent. Southern legislatures enacted statutes criminalizing the distribution of abolitionist literature, the circulation of antislavery newspapers, and speech deemed likely to incite enslaved populations. Possession of pamphlets, sermons, or newspapers could result in imprisonment or expulsion, and postal authorities cooperated in intercepting abolitionist mail.14 These laws did not require proof of insurrectionary intent. The expression of antislavery ideas alone was treated as inherently dangerous, collapsing the distinction between speech and action.

Extralegal enforcement reinforced formal suppression. Abolitionists faced mob violence, public humiliation, and economic retaliation, often with the tacit or explicit approval of local authorities. Printing presses were destroyed, meetings disrupted, and speakers assaulted or killed, while prosecutors declined to pursue charges against perpetrators. In Northern cities such as Boston, Cincinnati, and Alton, Illinois, mobs acted as unofficial enforcers of ideological conformity, signaling that dissent could be punished even where statutes were ambiguous or unenforced.15 The boundary between lawful governance and popular repression blurred, allowing communities to discipline moral opposition without invoking constitutional scrutiny.

Judicial doctrine offered little protection. Courts frequently upheld restrictions on abolitionist speech by appealing to doctrines of public order and community safety, emphasizing the government’s duty to prevent unrest. Even in Northern jurisdictions, judges treated abolitionist advocacy as provocational rather than deliberative, a distinction that justified restraint. The prevailing legal culture did not yet recognize political speech as categorically protected; instead, it evaluated expression based on perceived social consequences, granting authorities wide discretion to suppress unpopular ideas.16

The criminalization of abolitionist dissent reveals a crucial feature of American repression: moral opposition was most vulnerable when it challenged foundational social arrangements rather than discrete policies. Abolitionists did not merely argue that slavery was inefficient or unwise. They insisted it was unjust, sinful, and incompatible with republican principles. That claim destabilized constitutional compromises and economic interests alike, prompting a response that treated belief itself as a threat. The struggle over abolition thus exposed the limits of American tolerance for ideological dissent long before the Civil War forced the issue into open conflict.17

Civil War, Loyalty, and the Expansion of Executive Power

The outbreak of the Civil War transformed longstanding anxieties about dissent into an unprecedented expansion of federal authority. Faced with armed rebellion and the possibility of national disintegration, the Lincoln administration treated ideological opposition not merely as political disagreement but as a potential extension of enemy action. Loyalty became a governing principle, reshaping the relationship between citizens and the state as executive power expanded to meet what was framed as an existential emergency. The war did not invent repression, but it dramatically intensified the belief that dissent could not be safely tolerated in moments of national peril.

One of the most consequential assertions of executive authority involved the suspension of habeas corpus. President Lincoln authorized military officials to detain suspected disloyal persons without immediate judicial review, a power traditionally understood as belonging to Congress. Thousands of civilians were arrested, including journalists, political activists, and elected officials accused of discouraging enlistment or undermining Union morale.18 These detentions often occurred far from active battle zones, underscoring that ideological opposition, not military threat alone, lay at the heart of loyalty enforcement.

Military tribunals further blurred the boundary between civil law and wartime necessity. Civilians accused of disloyal speech or association were tried before military commissions rather than civilian courts, justified on the grounds that ordinary legal processes were inadequate in wartime. The most famous challenge to this system came after the war in Ex parte Milligan, when the Supreme Court ruled that military trials of civilians were unconstitutional where civil courts remained open.19 Yet the decision did not erase the wartime precedent. It confirmed that extraordinary measures had been taken, even if it limited their future application.

Public debate over these policies revealed deep divisions about the meaning of constitutional liberty in wartime. Supporters of the administration argued that dissent endangered soldiers and prolonged the conflict, framing repression as a regrettable but necessary defense of the Union. Critics countered that unchecked executive power threatened to destroy the very constitutional order the war was meant to preserve. The resulting tension exposed a recurring dilemma: whether constitutional rights were absolute principles or conditional privileges suspended in moments of crisis.20

The Civil War left a lasting imprint on American governance. While many wartime measures were rescinded after 1865, the conflict established powerful precedents for executive action during national emergencies. Future generations would repeatedly invoke the Civil War as justification for surveillance, detention, and speech restrictions, citing the survival of the nation as a higher imperative than procedural restraint. The war thus marked a turning point, embedding the logic of loyalty enforcement within the constitutional tradition and ensuring that dissent would remain vulnerable whenever national unity was again framed as a matter of survival.21

Reconstruction, Redemption, and the Repression of Radical Politics

The end of the Civil War did not resolve the problem of ideological dissent. It transformed it. Reconstruction introduced a radically expanded vision of citizenship grounded in emancipation, equal protection, and federal enforcement, unsettling long-standing hierarchies of race and power. For former Confederates and many white Southerners, these changes were experienced not as constitutional reform but as ideological occupation. Radical Republican policies were framed as illegitimate impositions, while Black political participation was recast as evidence of disorder rather than democratic inclusion.

The federal government initially responded by asserting unprecedented authority to protect the new constitutional order. Congress passed the Enforcement Acts to suppress white supremacist violence and defend Black suffrage, authorizing federal intervention against groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, whose campaigns of terror aimed explicitly to dismantle Reconstruction governments.22 These measures treated racial terror as a political crime rather than a local disturbance, recognizing that violence functioned as an ideological tool to reverse federal policy. For a brief period, dissent rooted in white supremacy was criminalized in defense of constitutional transformation.

That moment proved fragile. As Northern commitment to Reconstruction waned, the meaning of repression shifted. Federal authorities increasingly retreated from enforcement, while Southern states reclaimed control through what became known as Redemption. Former Confederates regained political power and redefined radical politics, particularly Black political organizing and interracial governance, as threats to public order.23 The same mechanisms once used to suppress white supremacist violence were dismantled or repurposed, revealing how the criminalization of dissent depended on who controlled the state.

State governments moved swiftly to neutralize radical opposition. New constitutions, electoral laws, and criminal statutes were deployed to restrict voting, weaken labor organizing, and criminalize behaviors associated with poverty and political mobilization. Vagrancy laws, contract enforcement regimes, and convict leasing systems transformed economic vulnerability into criminal liability, disproportionately targeting Black citizens and political dissidents.24 These legal structures did not openly ban dissent. They rendered it practically impossible by stripping targeted populations of the material and civic foundations necessary for sustained political participation.

Violence remained central to this process. Paramilitary groups and “rifle clubs” operated alongside formal law enforcement, intimidating voters, assassinating political leaders, and disrupting elections. Local officials frequently tolerated or facilitated such actions, blurring the line between lawful authority and extralegal coercion.25 Radical dissent was suppressed not only through statutes but through a climate of fear that communicated the costs of political opposition without requiring constant legal prosecution.

Judicial interpretation reinforced these outcomes. Supreme Court decisions narrowed the scope of federal enforcement and constitutional protection, emphasizing states’ rights over federal authority to police civil rights violations. By treating racial violence and political intimidation as matters of local concern, the Court effectively insulated Redemption regimes from sustained federal challenge.26 The law did not merely fail to protect dissent. It actively legitimated a political order built on its suppression.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Reconstruction’s radical promise had been largely dismantled. What remained was a powerful lesson in the selective criminalization of dissent. When radical politics aligned with federal authority, repression was justified as constitutional defense. When those same politics challenged local power and racial hierarchy, they were reframed as illegitimate, dangerous, or criminal. The Redemption era thus entrenched a pattern that would recur throughout American history: dissent would be protected or punished not by its principles but by its relationship to prevailing power.27

World War I and the Birth of Modern Political Policing

American entry into World War I marked a decisive shift in how the federal government conceptualized and managed ideological dissent. Unlike earlier conflicts, the war coincided with mass democracy, industrial labor unrest, and transnational radical movements, all of which intensified elite fears about internal cohesion. Political opposition was no longer treated primarily as localized disloyalty or partisan excess. It was reconceived as a systemic threat capable of undermining mobilization, production, and morale on a national scale. This reconceptualization laid the groundwork for a new, centralized apparatus of political policing.

Congressional action formalized this shift. The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 criminalized a broad range of expressive activity, including speech that interfered with military recruitment, criticized the war effort, or brought the government into disrepute. Enforcement quickly extended beyond espionage in any conventional sense, targeting socialists, labor organizers, pacifists, and antiwar activists whose opposition was ideological rather than operational.28 Federal authorities treated dissenting speech as a form of material harm, collapsing the distinction between expression and action in the name of national security.

Administrative institutions expanded to enforce these laws. The Department of Justice developed new investigative capacities, while the Bureau of Investigation began systematically collecting intelligence on political organizations and individuals. Private actors were drawn into this system through programs that encouraged citizens to report suspicious speech or behavior, effectively deputizing the public as ideological monitors.29 Surveillance, infiltration, and prosecution became routine tools of governance, establishing patterns that would persist long after the armistice.

Judicial doctrine initially accommodated this expansion. In cases such as Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court upheld convictions under the Espionage Act, endorsing the principle that speech could be punished if it posed a “clear and present danger” to government objectives.30 While later jurisprudence would narrow this standard, its wartime application legitimized the suppression of political belief during national emergencies. World War I thus produced not only a wave of prosecutions but a durable institutional and legal framework for modern political policing, embedding ideological surveillance within the machinery of the American state.

The First Red Scare and the Normalization of Ideological Surveillance

The end of World War I did not dismantle the machinery of repression built during wartime. Instead, it redirected it inward. As labor unrest, anarchist violence, and revolutionary upheaval abroad converged in the immediate postwar years, federal authorities framed radical ideology as an ongoing emergency rather than a temporary wartime aberration. The Bolshevik Revolution intensified fears that dissenting ideas could metastasize into domestic revolution, encouraging policymakers to treat political belief itself as an object of permanent suspicion rather than episodic concern. The transition from wartime repression to peacetime surveillance marked a critical shift in American governance.

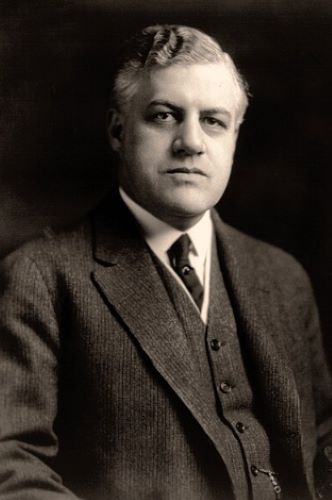

Federal enforcement reached its apex under Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, whose response to anarchist bombings fused law enforcement with ideological purification. The Palmer Raids of 1919–1920 involved mass arrests of suspected radicals, often without warrants, legal counsel, or clear evidence of criminal activity. Thousands were detained, interrogated, and held incommunicado, while hundreds of noncitizens were deported on the basis of political association rather than individual wrongdoing.31 These operations treated ideology as a proxy for criminal intent, normalizing guilt by belief and affiliation.

Administrative infrastructure expanded accordingly. The Bureau of Investigation developed centralized files on political organizations, labor unions, immigrant communities, and individual activists, creating a permanent archive of ideological suspicion. Surveillance extended beyond overt radicals to encompass reformers, educators, and civil liberties advocates whose positions diverged from prevailing norms.32 Intelligence gathering ceased to be an exceptional wartime measure and became a routine function of the federal state, justified by the presumed invisibility and persistence of subversive belief.

Immigration law provided a particularly flexible tool for repression. Deportation proceedings bypassed many constitutional protections afforded in criminal trials, allowing the government to remove individuals based on political doctrine rather than proven acts. Anarchism and communism were codified as deportable ideologies, collapsing the distinction between unlawful conduct and prohibited thought.33 The resulting regime disproportionately targeted immigrants, reinforcing the association between foreignness and ideological danger while insulating repression from judicial scrutiny.

Public reaction eventually curbed the most extreme abuses of the Red Scare, but the underlying logic endured. Congressional investigations, loyalty tests, and intelligence monitoring did not disappear. They were normalized. The First Red Scare demonstrated that large-scale ideological surveillance could be justified in the absence of declared war and that civil liberties could be subordinated to preventive security claims without permanently discrediting the institutions involved. The episode thus cemented a durable precedent: dissent need not produce violence to be policed. The anticipation of danger was enough.34

Cold War America and the Institutionalization of Anti-Communism

The onset of the Cold War transformed episodic repression into a durable system of ideological governance. Unlike earlier moments of crisis, anti-communism was not framed as a temporary response to emergency but as a permanent condition of national defense. The geopolitical rivalry with the Soviet Union encouraged American leaders to treat communism not merely as a hostile foreign power but as an internal contagion capable of eroding institutions from within. Ideological dissent associated with the left was thus recast as a matter of national security rather than political disagreement, legitimizing sustained surveillance and regulation of belief.

Federal loyalty programs formalized this logic. Beginning in the late 1940s, executive orders required millions of federal employees to undergo loyalty investigations assessing not only conduct but associations, reading habits, and political affiliations. Membership in organizations labeled “subversive” could result in dismissal regardless of evidence of disloyal action.35 These programs operated on a preventive premise, treating ideological proximity as sufficient risk and shifting the burden of proof onto individuals to demonstrate political innocence rather than criminal guilt.

Congressional investigations amplified this system through public spectacle. Committees such as the House Un-American Activities Committee summoned witnesses to testify about their political beliefs and associations, often compelling them to choose between self-incrimination and professional ruin. The hearings blurred legal and moral judgment, transforming dissent into a performative trial of loyalty conducted before the nation.36 While framed as fact-finding exercises, these proceedings functioned as instruments of intimidation, reinforcing the idea that ideological nonconformity warranted exposure and sanction.

Criminal law reinforced these pressures through statutes that punished belief indirectly. The Smith Act authorized prosecution for advocating the overthrow of the government, even absent concrete plans or imminent action. Courts upheld convictions based on abstract doctrine and association, endorsing a theory of conspiracy that treated shared ideology as evidence of collective intent.37 The law thus collapsed the distinction between teaching, discussion, and action, converting political theory into prosecutable threat.

The cultural consequences of this regime extended far beyond formal prosecution. Blacklists in entertainment, education, and labor deprived thousands of employment without due process, relying on informal coordination between government agencies and private institutions. Fear of association produced widespread self-censorship, narrowing the range of permissible debate and discouraging collective action. Anti-communism became not only a state project but a social norm, enforced through reputational harm as much as legal sanction.38

Judicial resistance emerged gradually but incompletely. Supreme Court decisions in the late 1950s narrowed the scope of permissible prosecution, emphasizing the difference between abstract advocacy and incitement. Yet these rulings did not dismantle the loyalty system itself. By the time legal doctrine shifted, the infrastructure of surveillance, investigation, and ideological vetting was firmly embedded within American institutions. Cold War anti-communism thus marked a turning point, transforming dissent policing from episodic reaction into routine governance and leaving a legacy that would shape subsequent responses to perceived ideological threats.39

Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Limits of Tolerance

The postwar expansion of civil liberties did not produce a straightforward increase in tolerance for dissent. Instead, the mid-twentieth century revealed how selectively those liberties were applied when dissent challenged entrenched power. The civil rights movement exposed this contradiction with particular clarity. While activists appealed to constitutional guarantees and democratic ideals, state and local authorities frequently treated their demands as threats to public order rather than claims to equal citizenship. Nonviolent protest was recast as provocation, and moral opposition to segregation was framed as an incitement to disorder rather than a call for justice.

Law enforcement agencies responded with a combination of overt repression and covert surveillance. Southern officials used criminal statutes governing trespass, assembly, and breach of the peace to arrest demonstrators, while federal agencies monitored movement leaders under the suspicion that civil rights activism masked subversive intent. The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s COINTELPRO operations targeted organizations and individuals deemed disruptive, blurring the line between lawful dissent and national security threat.40 Surveillance and infiltration treated political mobilization itself as suspicious, particularly when it challenged racial hierarchy or demanded structural change.

Judicial intervention offered uneven protection. Supreme Court decisions expanded constitutional safeguards for protest and association, yet enforcement lagged behind doctrine. Local courts and police departments often ignored or circumvented rulings that constrained repression, relying on discretionary arrest and prolonged detention to sap movements of momentum. Even when convictions were overturned, the cumulative effect of repeated arrests, legal costs, and physical violence imposed significant burdens on dissenters.41 Rights existed in principle, but their realization depended on sustained confrontation with state power.

Opposition to the Vietnam War intensified these dynamics on a national scale. Antiwar protest challenged not only a specific policy but the credibility of Cold War authority itself. Demonstrations, draft resistance, and campus organizing were met with expanded surveillance, infiltration, and prosecution under statutes originally designed for wartime repression.42 Government officials portrayed dissent as undermining troop morale and emboldening foreign enemies, reviving familiar arguments that equated ideological opposition with national danger.

By the late 1960s, the limits of tolerance were unmistakable. Civil rights and antiwar activists encountered a state willing to accommodate dissent rhetorically while policing it aggressively in practice. Surveillance programs expanded even as public rhetoric celebrated democratic pluralism, and protest was increasingly managed as a security problem rather than a political conversation. The period revealed a persistent pattern: when dissent threatened foundational arrangements of power or legitimacy, legal protections proved contingent and reversible. The promise of tolerance endured, but its application remained conditional.43

The War on Terror and the Elastic Meaning of Subversion

The attacks of September 11, 2001 produced a political climate in which dissent was once again reframed through the language of existential threat. Unlike earlier wars, the War on Terror was defined not by a finite enemy or geographic boundary but by an open-ended struggle against a tactic and an ideology. This ambiguity expanded the state’s interpretive authority, allowing political opposition, religious expression, and associational activity to be scrutinized under an elastic concept of subversion. Fear of infiltration and radicalization encouraged officials to treat belief, sympathy, and rhetoric as early indicators of danger rather than protected forms of expression.

Congressional response codified this shift. The USA PATRIOT Act dramatically expanded surveillance powers, lowered evidentiary thresholds, and broadened the definition of material support for terrorism, enabling the government to investigate individuals and organizations without demonstrating direct involvement in violent acts.44 These provisions collapsed traditional distinctions between advocacy and assistance, exposing political and humanitarian activity to criminal liability when it intersected with designated groups or causes. The law did not require intent to further violence. Association itself became a sufficient trigger for state intervention.

Executive authority expanded in parallel. The designation of “enemy combatants” allowed the executive branch to detain individuals indefinitely without criminal charge, relying on national security classification rather than judicial process. While initially applied to foreign nationals, the logic of extrajudicial detention raised profound questions about constitutional limits, particularly when American citizens were subjected to similar treatment.45 Dissenting voices that questioned the legality or morality of these practices were often portrayed as naïve or disloyal, echoing earlier patterns in which critique was equated with sympathy for the enemy.

Surveillance practices further blurred the boundary between security and ideological monitoring. Intelligence agencies collected vast quantities of metadata, monitored religious institutions, and infiltrated activist organizations under the rationale of preventive intelligence gathering. Muslim communities experienced particularly intense scrutiny, with routine religious and political expression treated as potential indicators of radicalization.46 The presumption of innocence gave way to a model of risk management in which dissenting belief was assessed probabilistically rather than judged through individualized evidence of wrongdoing.

Judicial response was fragmented. Courts imposed some limits on executive power, particularly regarding detention and military commissions, yet they often deferred to national security claims when assessing surveillance and secrecy. The result was a partial normalization of emergency governance, in which extraordinary measures persisted long after the immediate crisis had passed.47 Legal challenges revealed the difficulty of contesting repression once it had been institutionalized through classified programs and broad statutory authority.

The War on Terror thus reaffirmed a recurring dynamic in American history. Ideological dissent did not need to advocate violence to fall under suspicion. It needed only to intersect with a narrative of threat. By redefining subversion as a matter of association, belief, or rhetorical alignment, the post-9/11 state expanded the reach of repression while preserving the formal language of constitutional order. The elasticity of subversion ensured that dissent remained legally precarious, particularly when it challenged the moral or strategic foundations of permanent war.48

Contemporary Dissent and the Revival of Punitive Rhetoric

In the early twenty-first century, ideological dissent has reemerged as a central object of political anxiety, even as formal commitments to free expression remain rhetorically intact. Polarization, digital communication, and declining trust in institutions have altered how dissent is perceived and managed. Political opposition is increasingly framed not as disagreement within a shared civic framework but as evidence of moral corruption, disinformation, or existential threat. This shift has revived punitive rhetoric that treats dissenting belief as a problem to be neutralized rather than engaged.

Law enforcement and national security institutions have adapted older frameworks to new conditions. Domestic extremism has become a flexible category through which protest movements, online communities, and ideological networks are assessed for threat potential. While violent acts remain the formal trigger for prosecution, expansive monitoring often precedes criminal conduct, relying on association, rhetoric, and digital behavior as indicators of risk.49 Preventive logic has again displaced individualized suspicion, extending surveillance into spaces of lawful political expression.

Protest policing offers a visible manifestation of this trend. Demonstrations across the political spectrum have been met with aggressive crowd-control tactics, expansive use of arrest authority, and the strategic deployment of disorder-related charges. These measures are justified as neutral public safety responses, yet they frequently operate to deter participation and exhaust movements through legal pressure rather than adjudicated guilt.50 Dissent is managed administratively, with the costs of engagement imposed long before any judicial determination of wrongdoing.

Digital platforms have further complicated the boundary between private governance and state power. Content moderation policies, algorithmic amplification, and coordinated reporting campaigns shape which ideas circulate and which are suppressed, often without transparent standards or meaningful appeal. Government officials routinely pressure platforms to address perceived threats, blurring the line between voluntary moderation and informal state coercion.51 Ideological dissent may be curtailed not through statute but through infrastructural dependence on privately controlled communication systems.

Rhetorical escalation has accompanied these developments. Political leaders increasingly describe opponents as enemies of democracy, traitors, or existential dangers, language that primes audiences to accept punitive responses. Such framing does not require immediate legal action to be effective. It conditions public expectations, lowers tolerance for dissent, and legitimizes extraordinary measures when they are eventually proposed. The boundary between speech regulation and political discipline becomes easier to cross once dissent is portrayed as inherently destabilizing.52

Contemporary dissent thus exists within a familiar historical pattern. While the mechanisms differ, the underlying logic remains consistent with earlier episodes of repression. Ideological opposition is framed as a precursor to disorder, surveillance precedes criminality, and punishment is justified as prevention rather than retaliation. The revival of punitive rhetoric signals not a departure from American tradition but its continuation, demonstrating once again how readily the language of security and civic preservation can be turned against political belief itself.53

Conclusion: The Enduring Boundary Between Dissent and Disloyalty

Across more than two centuries of American history, efforts to criminalize or punish ideological dissent have followed a remarkably consistent logic. Dissent has rarely been rejected outright as illegitimate in principle. Instead, it has been conditionally tolerated, protected only so long as it does not challenge dominant structures of power, legitimacy, or national identity. When political belief has been framed as threatening cohesion, security, or moral order, legal restraint has repeatedly given way to loyalty enforcement. This pattern reveals that the boundary between dissent and disloyalty has never been fixed. It has been actively constructed and reconstructed in response to fear.

What distinguishes American repression is not its absence of constitutional language but its coexistence with it. Sedition laws, loyalty oaths, surveillance programs, and administrative sanctions have consistently been justified as temporary deviations necessary to preserve a larger constitutional project. Yet those deviations have accumulated, leaving behind institutional habits and legal precedents that normalize ideological policing. Emergency measures have proven durable, even when the emergencies that produced them faded, a dynamic visible from the Alien and Sedition Acts through Cold War loyalty programs and post-9/11 surveillance regimes.54 The constitutional order has survived, but often by absorbing rather than rejecting the logic of repression.

The historical record also demonstrates that dissent is most vulnerable when it challenges foundational arrangements rather than discrete policies. Abolitionism, Reconstruction-era radicalism, labor organizing, civil rights activism, and antiwar protest all provoked punitive responses precisely because they questioned who belonged, who governed, and whose interests the state existed to serve. In these moments, ideological dissent was reframed as social danger, allowing belief itself to be treated as actionable harm. The law did not merely fail to protect dissent. It frequently participated in its suppression, reflecting prevailing hierarchies rather than neutral principle.55

Understanding this history carries implications beyond retrospective judgment. It underscores that free expression in the United States has never been self-executing or permanently secured. Its protection has depended on political will, institutional courage, and public tolerance for disagreement that cuts deeply against comfort and consensus. When dissent is once again described as disinformation, extremism, or civic sabotage, the historical record offers a warning rather than reassurance. The boundary between dissent and disloyalty has always been elastic. Whether it contracts or holds depends not on constitutional text alone, but on whether a democratic society is willing to accept the risks inherent in allowing political belief to remain free.56

Appendix

Footnotes

- Leonard W. Levy, Emergence of a Free Press (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 1–36.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), 53–90.

- Geoffrey R. Stone, Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism (New York: W. W. Norton, 2004), 15–38.

- Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), 161–198.

- Robert M. Calhoon, The Loyalists in Revolutionary America, 1760–1781 (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973), 409–447.

- Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 68–90.

- Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (New York: Knopf, 2011), 12–41.

- Levy, Emergence of a Free Press, 297–335.

- James Morton Smith, Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1956), 159–210.

- James Madison, “Virginia Resolutions,” 1798, in The Papers of James Madison, vol. 17, ed. David B. Mattern et al. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991), 185–190.

- Stone, Perilous Times, 29–45.

- Saul Cornell, The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 212–238.

- William Lee Miller, Arguing About Slavery: John Quincy Adams and the Great Battle in the United States Congress (New York: Knopf, 1996), 263–305.

- Clement Eaton, The Freedom-of-Thought Struggle in the Old South (New York: Harper & Row, 1940), 84–122.

- Leonard L. Richards, Gentlemen of Property and Standing: Anti-Abolition Mobs in Jacksonian America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 3–41.

- David M. Rabban, Free Speech in Its Forgotten Years, 1870–1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 18–32.

- Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W. W. Norton, 2010), 27–52.

- Mark E. Neely Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 10–47.

- Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. (4 Wall.) 2 (1866).

- Daniel Farber, Lincoln’s Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 157–201.

- Stone, Perilous Times, 65–92.

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 425–454.

- Heather Cox Richardson, The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post–Civil War North, 1865–1901 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 83–117.

- Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2008), 53–92.

- Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 17–48.

- The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883).

- C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955), 33–65.

- Christopher Capozzola, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 19–47.

- Beverly Gage, The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in Its First Age of Terror (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 71–103.

- Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919).

- Robert K. Murray, Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919–1920 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1955), 137–189.

- J. Edgar Hoover, Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America and How to Fight It (New York: Henry Holt, 1958), 23–41.

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 56–90.

- Stone, Perilous Times, 125–153.

- Ellen Schrecker, Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America (Boston: Little, Brown, 1998), 87–123.

- Richard M. Fried, Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 45–78.

- Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951).

- Victor S. Navasky, Naming Names (New York: Viking Press, 1980), 19–54.

- Stone, Perilous Times, 191–227.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, COINTELPRO: The FBI’s Covert Action Programs Against American Citizens (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976), 1–35.

- Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 778–812.

- Melvin Small, Antiwarriors: The Vietnam War and the Battle for America’s Hearts and Minds (Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 2002), 95–132.

- David Cole and Jules Lobel, Less Safe, Less Free: Why America Is Losing the War on Terror (New York: The New Press, 2007), 41–67.

- USA PATRIOT Act, Pub. L. No. 107-56, 115 Stat. 272 (2001).

- Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004).

- American Civil Liberties Union, Mapping Muslims: NYPD Spying and Its Impact on American Muslims (New York: ACLU, 2013), 9–38.

- David Cole, Enemy Aliens: Double Standards and Constitutional Freedoms in the War on Terrorism (New York: The New Press, 2003), 137–176.

- Aziz Rana, The Two Faces of American Freedom (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 245–278.

- Samuel J. Walker, In Defense of American Liberties: A History of the ACLU (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 312–338.

- Alex S. Vitale, The End of Policing (London: Verso, 2017), 179–214.

- Jack M. Balkin, “Free Speech Is a Triangle,” Columbia Law Review 118, no. 7 (2018): 2011–2055.

- Corey Robin, The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Donald Trump (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 7–29.

- Stone, Perilous Times, 301–327.

- Stone, Perilous Times, 329–362.

- Rana, The Two Faces of American Freedom, 281–318.

- David Kairys, With Liberty and Justice for Some: A Critique of the Conservative Supreme Court (New York: The New Press, 1993), 3–27.

Bibliography

- Adorno, Rolena. The Polemics of Possession in Spanish American Narrative. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- American Civil Liberties Union. Mapping Muslims: NYPD Spying and Its Impact on American Muslims. New York: ACLU, 2013.

- Balkin, Jack M. “Free Speech Is a Triangle.” Columbia Law Review 118, no. 7 (2018): 2011–2055.

- Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York: Anchor Books, 2008.

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988.

- Calhoon, Robert M. The Loyalists in Revolutionary America, 1760–1781. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973.

- Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Cole, David. Enemy Aliens: Double Standards and Constitutional Freedoms in the War on Terrorism. New York: The New Press, 2003.

- Cole, David, and Jules Lobel. Less Safe, Less Free: Why America Is Losing the War on Terror. New York: The New Press, 2007.

- Cornell, Saul. The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

- Eaton, Clement. The Freedom-of-Thought Struggle in the Old South. New York: Harper & Row, 1940.

- Farber, Daniel. Lincoln’s Constitution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- —-. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: W. W. Norton, 2010.

- Fried, Richard M. Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Gage, Beverly. The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in Its First Age of Terror. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Hoover, J. Edgar. Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America and How to Fight It. New York: Henry Holt, 1958.

- Jasanoff, Maya. Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World. New York: Knopf, 2011.

- Kairys, David. With Liberty and Justice for Some: A Critique of the Conservative Supreme Court. New York: The New Press, 1993.

- Levy, Leonard W. Emergence of a Free Press. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Lemann, Nicholas. Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

- Maier, Pauline. From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776. New York: W. W. Norton, 1972.

- Madison, James. “Virginia Resolutions.” 1798. In The Papers of James Madison, vol. 17, edited by David B. Mattern et al., 185–190. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991.

- Miller, William Lee. Arguing About Slavery: John Quincy Adams and the Great Battle in the United States Congress. New York: Knopf, 1996.

- Murray, Robert K. Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919–1920. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1955.

- Navasky, Victor S. Naming Names. New York: Viking Press, 1980.

- Neely, Mark E., Jr. The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Rabban, David M. Free Speech in Its Forgotten Years, 1870–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Rana, Aziz. The Two Faces of American Freedom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Richards, Leonard L. Gentlemen of Property and Standing: Anti-Abolition Mobs in Jacksonian America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- Richardson, Heather Cox. The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post–Civil War North, 1865–1901. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Robin, Corey. The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Donald Trump. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Schrecker, Ellen. Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Boston: Little, Brown, 1998.

- Small, Melvin. Antiwarriors: The Vietnam War and the Battle for America’s Hearts and Minds. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 2002.

- Smith, James Morton. Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1956.

- Stone, Geoffrey R. Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism. New York: W. W. Norton, 2004.

- Vitale, Alex S. The End of Policing. London: Verso, 2017.

- Walker, Samuel J. In Defense of American Liberties: A History of the ACLU. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Wood, C. Vann. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. New York: Oxford University Press, 1955.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.