The fear of standing armies that shaped English and American constitutional thought was neither exaggerated nor abstract. It was grounded in direct historical experience.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Order, Force, and the Memory of Trauma

Modern constitutional suspicion of standing armies did not arise from abstract political theory or philosophical speculation. It emerged from lived experience. Seventeenth-century England learned, through civil war and military rule, that armies raised to restore order rarely relinquish power easily. The trauma of that experience reshaped how English political thinkers understood authority, force, and civilian governance. Constitutional restraint was not an idealistic aspiration. It was a defensive response to memory.

The English Civil War shattered long-standing assumptions about the relationship between ruler, parliament, and people. What began as a struggle over taxation, religion, and royal prerogative escalated into armed conflict that dissolved the boundaries between civil authority and military power. Once violence became the means of political resolution, control of armed force became the central question of legitimacy. Order, once grounded in law and custom, increasingly depended on who commanded soldiers.

The creation and persistence of the New Model Army transformed this crisis into something deeper. Unlike earlier levies raised for specific campaigns, this was a professional, ideologically coherent force with a continuing political presence. Its soldiers did not simply fight battles. They intervened in governance, pressured parliament, and ultimately enforced constitutional outcomes. When Oliver Cromwell assumed power, he did so not as a king, but as a military-backed executive who justified authority through necessity rather than consent.

This experience permanently altered English constitutional thinking. Standing armies came to be understood not as neutral instruments of security, but as latent threats to civilian rule. Fear of military power was not hypothetical. It was learned through direct exposure to administrative coercion, dissolved parliaments, and governance enforced by arms. The insistence on civilian control, legislative authorization, and suspicion of domestic military deployment that followed was not paranoia. It was memory hardening into doctrine.

England before the Civil War: Authority without Permanent Arms

Before the mid-seventeenth century, English political culture was shaped by a deep suspicion of permanent military force within the realm. Authority rested on law, custom, and negotiated consent rather than coercive presence. Kings possessed the right to command, but not to maintain a standing domestic army independent of parliamentary approval. The absence of permanent armed force was not a weakness of the system. It was one of its safeguards.

Military power in early modern England was episodic and conditional. Forces were raised for specific purposes, funded temporarily, and disbanded when the immediate need passed. Local militias rather than professional soldiers formed the backbone of domestic defense, reinforcing the principle that arms belonged to the community rather than the executive. This arrangement limited the crown’s capacity to impose its will by force and tied military mobilization to civilian structures.

Parliamentary control over taxation reinforced this restraint. Without legislative authorization, sustained military funding was impossible. The crown’s dependence on parliamentary grants ensured that war-making and domestic security remained politically accountable. Even during periods of external threat, the idea that the executive might retain armed force indefinitely within England itself provoked anxiety. Power without disbandment signaled danger.

These arrangements were not merely practical compromises. They reflected a broader political assumption that liberty depended on the absence of permanent coercive instruments. English constitutional tradition did not deny the necessity of force altogether. It insisted instead that force remain subordinate, temporary, and publicly accountable. When that balance collapsed during the Civil War, the resulting trauma reshaped constitutional thought for generations.

Civil War and the Creation of the New Model Army

The English Civil War forced Parliament to confront a dilemma it had long sought to avoid: how to wage sustained war without surrendering civilian supremacy to military force. Early reliance on local militias and ad hoc levies proved inadequate against royalist armies. Military inefficiency, divided command, and inconsistent discipline undermined parliamentary efforts, leading reformers to conclude that victory required a fundamentally different kind of force. Necessity, not ideology, drove the creation of the New Model Army.

Established in 1645, the New Model Army marked a sharp departure from England’s traditional approach to military power. It was centrally organized, professionally trained, regularly paid, and placed under unified command. Promotion increasingly reflected competence rather than social rank, fostering cohesion and effectiveness. For the first time, England possessed a permanent national army capable of sustained domestic deployment. What began as a wartime solution quietly altered the balance between civilian authority and armed force.

The army’s professionalism carried political consequences. Soldiers who served continuously, received wages, and depended on military service for livelihood developed a collective identity distinct from civilian society. Religious and ideological commitments further reinforced this cohesion, binding troops not only to commanders but to a shared sense of moral purpose. The army was no longer merely executing parliamentary will. It began to understand itself as a guardian of the political settlement it had fought to secure.

As the war drew toward its conclusion, the New Model Army emerged as an independent political actor. Disputes over pay, indemnity, and disbandment exposed the fragility of parliamentary control. Soldiers petitioned, debated, and resisted civilian directives, asserting that they possessed a legitimate voice in determining England’s future. The army’s physical presence, combined with its organizational unity, allowed it to exert pressure without formally seizing power.

The creation of the New Model Army thus resolved one crisis while inaugurating another. Parliament won the war, but at the cost of introducing a permanent military force into domestic politics. The precedent was irreversible. Once political outcomes depended on armed organization, civilian authority could no longer assume unquestioned primacy. The army that secured victory would soon reshape governance itself, not through rebellion, but through sustained proximity to power.

Cromwell’s Rule and the Reality of Military Government

Oliver Cromwell did not initially present himself as a revolutionary despot. He framed his authority as provisional, reluctant, and necessary. The execution of Charles I and the abolition of the monarchy left England without a familiar constitutional anchor, and Cromwell repeatedly insisted that order, godly reform, and national stability required firm guidance. Military authority, in this telling, was not a replacement for civilian rule but a temporary scaffold erected to prevent chaos.

Yet the political reality of Cromwell’s rule revealed how difficult it was to disentangle necessity from domination once armed force became the guarantor of order. The Rump Parliament’s survival depended on the army’s tolerance, and its dissolution in 1653 demonstrated where ultimate power lay. Cromwell’s decision to dismiss Parliament by force was justified as a corrective to corruption and paralysis, but it marked a decisive subordination of civilian authority to military-backed executive judgment.

The establishment of the Protectorate formalized this arrangement without resolving its contradictions. Cromwell governed through written constitutions, councils, and legal forms, preserving the appearance of legality while relying on military support to enforce compliance. The Instrument of Government and later the Humble Petition and Advice sought to regularize authority, but neither eliminated the army’s central role. Governance functioned, but it did so under the shadow of coercive enforcement.

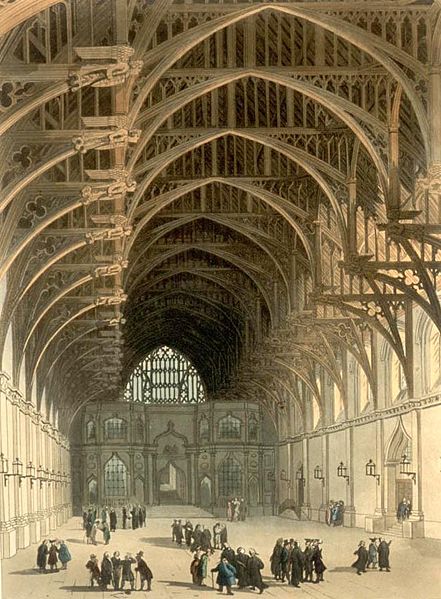

The rule of the major-generals exposed the underlying logic of military government most clearly. England was divided into military districts overseen by officers responsible for maintaining order, enforcing moral regulation, and suppressing dissent. These measures were presented as necessary responses to disorder and royalist threat, yet they effectively militarized civilian administration. Law enforcement and governance merged into a single coercive apparatus, blurring the distinction between civil order and martial control.

Importantly, Cromwell’s regime was not universally brutal nor uniformly unpopular. Many welcomed the stability it imposed after years of war. Courts functioned, commerce resumed, and violence diminished. This partial success made military government more insidious rather than less. Order achieved through force appeared to validate the method, even as it entrenched the precedent that civilian governance required armed supervision.

Cromwell’s death revealed the fragility of this arrangement. Without his personal authority, the Protectorate collapsed rapidly, and the army proved incapable of sustaining legitimacy on its own. The Restoration that followed was not merely a return to monarchy but a repudiation of military rule as a governing principle. The lesson drawn was unmistakable: armies raised to restore order do not easily surrender power, and governance enforced by force corrodes the very authority it claims to protect.

The Standing Army as Constitutional Nightmare

The Restoration of the monarchy did not erase the memory of military rule. Instead, it fixed that memory at the center of English constitutional consciousness. Cromwell’s regime taught a durable lesson: a standing army loyal to the executive represented the most direct internal threat to liberty. The danger was not invasion or rebellion from below, but governance enforced by soldiers who answered to power rather than law.

Postwar political discourse treated standing armies as inherently destabilizing, regardless of their stated purpose. Even armies raised to preserve order were now understood as instruments that could impose obedience without consent. The experience of the New Model Army had demonstrated that once armed force became permanent, it acquired interests, loyalties, and momentum independent of civilian institutions. Temporary necessity had revealed a permanent risk.

This fear reshaped how authority itself was understood. Power backed by soldiers could bypass Parliament, silence opposition, and enforce compliance while maintaining a veneer of legality. The issue was not merely the presence of troops, but their permanence and domestic deployment. An army that could not be easily disbanded could not be reliably controlled. Executive possession of force threatened to turn constitutional government into conditional tolerance.

As a result, the standing army became the defining constitutional nightmare of post-civil war England. Safeguards against it were not expressions of ideological hostility toward order or security. They were defensive responses to historical trauma. English constitutional thought hardened around the conviction that liberty required the absence of permanent military power within civil society. That conviction would echo powerfully across the Atlantic in the following century.

From English Trauma to Constitutional Doctrine

The fear of standing armies did not remain an emotional reaction to past events. It hardened into constitutional principle. Post–Civil War England sought to ensure that the conditions which enabled military rule could not easily recur. The experience of Cromwell’s regime transformed suspicion into structure, embedding restraints on military power directly into the legal and political framework of the state.

Central to this transformation was Parliament’s insistence on legislative control over military funding. By requiring regular authorization for army maintenance, Parliament ensured that no executive could sustain a permanent force without continued civilian consent. This principle culminated in the Bill of Rights of 1689, which explicitly declared standing armies in peacetime unlawful without parliamentary approval. The lesson of the Civil War was now codified: force must answer to law, not necessity alone.

Equally important was the reaffirmation of civilian supremacy. Military command remained subordinate to civil authority, and the army was treated as an instrument rather than an independent political actor. The legal framework did not deny the need for defense, but it insisted that defense be governed, temporary, and accountable. Military obedience was reoriented away from personal loyalty and toward institutional control, reflecting the trauma of commanders who had once ruled through arms.

These doctrines were not expressions of theoretical purity. They were preventative measures shaped by memory. England’s constitutional settlement after the seventeenth century was built on the recognition that liberty is most vulnerable when order is enforced by permanent force. By translating trauma into doctrine, English constitutionalism sought to ensure that emergency would never again become a governing norm.

Transatlantic Transmission: From England to America

English constitutional fears surrounding standing armies crossed the Atlantic largely intact. American colonists did not encounter these ideas as abstract inheritances, but as living political assumptions embedded in English law, pamphlets, and parliamentary practice. The memory of Cromwellian military rule and the post–Civil War settlement shaped how English liberty was taught, discussed, and defended throughout the colonies. Suspicion of permanent armed force was part of the political air colonists breathed long before independence was contemplated.

Colonial experience reinforced rather than diluted this inheritance. British troops stationed in North America during the eighteenth century were widely perceived not as protectors, but as instruments of coercion. Quartering, patrols, and military enforcement of civil law echoed precisely the abuses English constitutionalism warned against. The presence of professional soldiers answering to imperial authority confirmed colonial fears that standing armies existed to discipline populations, not merely to defend them.

Political rhetoric during the imperial crisis drew explicitly on English precedent. Pamphleteers and legislators invoked seventeenth-century history to frame British actions as constitutional violations rather than novel oppression. Standing armies were described as tools of executive domination, incompatible with liberty and self-government. The argument was not revolutionary in origin. It was conservative in the deepest sense, grounded in inherited constitutional memory.

These concerns shaped the American revolutionary imagination well before open conflict began. Resistance was justified as defense of civilian authority against military encroachment. Colonial militias were celebrated precisely because they embodied the opposite principle of a standing army. They were temporary, locally controlled, and subordinate to civilian leadership. The contrast was central to American political identity as it formed.

When independence forced Americans to design their own constitutional order, English trauma provided both warning and blueprint. The fear was not that armies were unnecessary, but that they were politically dangerous. Civilian supremacy, legislative authorization, and strict limits on domestic military deployment were treated as foundational safeguards. American constitutional thought did not innovate these principles. It preserved them, convinced that forgetting their origins would invite their violation.

Emergency Power and the Temptation of Force

The constitutional fear of standing armies was inseparable from a broader suspicion of emergency power. English and American traditions recognized that emergencies invite shortcuts, and shortcuts invite force. The language of necessity has always carried a dangerous appeal, promising swift resolution when ordinary procedures appear inadequate. Yet the seventeenth century demonstrated that emergencies rarely remain bounded, and that authority expanded under pressure is seldom fully relinquished.

Emergency power alters political expectations even when it is framed as temporary. Once executives learn that extraordinary authority can bypass deliberation, the incentive to preserve normal limits weakens. Legislative processes appear slow, judicial oversight appears obstructive, and civilian consent appears expendable. The appeal of force lies not only in its effectiveness, but in its clarity. It resolves conflict without negotiation, replacing persuasion with command.

This temptation was precisely what post–Civil War constitutional doctrine sought to restrain. Emergency statutes and exceptional powers were tolerated only when tightly circumscribed, time-limited, and subject to civilian review. The memory of Cromwell’s rule taught that force justified by crisis quickly becomes force justified by convenience. What begins as protection against disorder risks becoming a governing method in its own right.

The enduring lesson is not that emergencies are fictional, but that they are politically transformative. When executives invoke emergency authority to bypass civilian limits, they recreate the conditions that earlier constitutional systems were designed to prevent. The temptation of force does not announce tyranny. It presents itself as responsibility. Republics falter not when force is used, but when its use becomes administratively acceptable.

Administrative Decay Rather Than Sudden Tyranny

The danger that haunted English and American constitutional thought was not sudden dictatorship, but gradual administrative erosion. Military domination rarely announced itself through dramatic seizure of power. It emerged instead through routine decisions that expanded executive discretion, normalized exceptional authority, and quietly displaced civilian oversight. By the time tyranny became visible, it had already been institutionalized through procedure.

This process was especially difficult to recognize because legality often remained intact. Statutes were passed, courts continued to operate, and officials acted under color of law. Emergency powers were framed as temporary, limited, and necessary, even as their repeated use altered the balance of authority. Administrative continuity masked constitutional decay, allowing coercive practices to embed themselves within ordinary governance.

Military force played a critical role in this transformation not by overthrowing civilian institutions outright, but by redefining their function. When soldiers enforce policy internally, civilian authority becomes conditional. Law ceases to mediate conflict and instead follows force. Obedience replaces consent as the foundation of order. In such systems, repression can appear lawful precisely because it is bureaucratically managed.

The English Civil War and its aftermath taught that tyranny need not arrive violently to succeed. It can advance quietly, through habits of emergency and administrative convenience. Constitutional collapse, in this sense, is not a moment but a condition. It occurs when extraordinary measures cease to feel extraordinary and when force becomes an acceptable substitute for civilian rule.

Conclusion: Why the Fear Was Rational

The fear of standing armies that shaped English and American constitutional thought was neither exaggerated nor abstract. It was grounded in direct historical experience. Seventeenth-century England learned, at tremendous cost, that military force introduced into domestic governance does not remain politically neutral. Once soldiers become arbiters of order, civilian authority survives only at their discretion. The resulting trauma produced not paranoia, but prudence.

What the English Civil War revealed was not simply the danger of violent overthrow, but the subtler threat of administrative transformation. Cromwell’s regime did not abolish law outright. It governed through it, reshaping legal forms to accommodate military enforcement. This lesson proved enduring: legality can coexist with coercion, and order can be maintained even as liberty erodes. Constitutional safeguards against standing armies were designed precisely to prevent this quiet substitution of force for consent.

The American Founders inherited this understanding intact. Their insistence on civilian control, legislative authorization, and suspicion of domestic military deployment reflected historical memory rather than theoretical hostility to security. Armies were acknowledged as necessary, but dangerous. Emergency powers were accepted as unavoidable, but corrosive. The fear was not that force would be used, but that its use would become normal.

Remembering why these limits exist matters as much as the limits themselves. Constitutional restraint loses meaning when its historical origins are forgotten. The English experience demonstrated that republics do not fall when order collapses, but when it is preserved by the wrong means. The fear of standing armies was rational because it recognized a truth learned through trauma: force that answers to necessity rather than civilian law does not defend liberty. It replaces it.

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. State of Exception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Blackstone, William. Commentaries on the Laws of England. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1765–1769.

- Braddick, Michael J. God’s Fury, England’s Fire: A New History of the English Civil Wars. London: Penguin, 2008.

- Brewer, John. The Sinews of Power: War, Money, and the English State, 1688–1783. New York: Knopf, 1989.

- Clayton, William. “John Harris, the Oxford Army Press, and the Radicalizing Process.” The Seventeenth Century 38:5 (2023): 785-811.

- Dicey, A. V. Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution. London: Macmillan, 1885.

- Gentles, Ian. The New Model Army in England, Ireland and Scotland, 1645–1653. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

- Hill, Christopher. God’s Englishman: Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. London: Penguin, 1970.

- —-. The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution. London: Penguin, 1972.

- Kishlansky, Mark. “The Case of the Army Truly Stated: The Creation of the New Model Army.” Past & Present 81 (1978): 51-74.

- Morrill, John. The Nature of the English Revolution. London: Longman, 1993.

- Pocock, J. G. A. The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957.

- —-. The Machiavellian Moment. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- Preble, Christopher A. “The Founders, Executive Power, and Military Intervention.” Pace Law Review 30:2 (2010): 688-719.

- Rakove, Jack N. Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution. New York: Knopf, 1996.

- Russell, Conrad. The Causes of the English Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Sharpe, Kevin. The Personal Rule of Charles I. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

- Worden, Blair. The Rump Parliament, 1648–1653. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.21.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.