Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

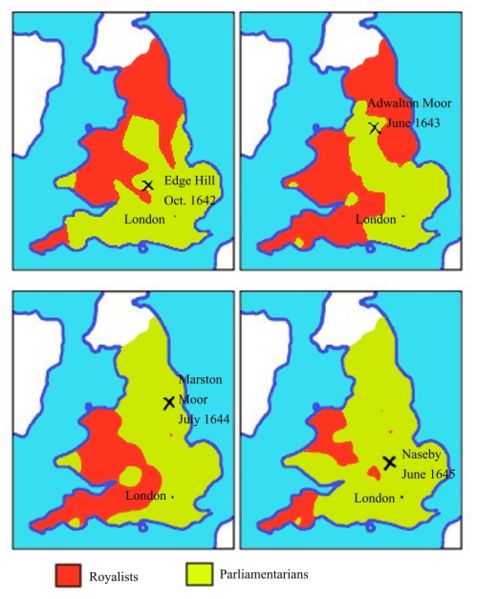

The term English Civil War (or Wars) refers to the series of armed conflicts and political machinations which took place between Parliamentarians (often called the Roundheads) and Royalists (or the cavaliers) from 1642 until 1651. The first (1642-1645) and the second (1648-1649) civil wars pitted the supporters of King Charles I against the supporters of the Long Parliament, while the third (1649-1651) saw fighting between supporters of King Charles II and supporters of the Rump Parliament. The third war ended with the Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651.

These wars were between supporters of the king’s right to absolute authority, and supporters of the rights of Parliament—which, while not a fully democratic institution—did represent a check on the power of the monarch. Many of those involved also had religious preferences concerning how the established church should be organized—for example, with or without bishops, and whether its style of worship would be more or less liturgical. Some of those involved advocated religious freedom, and separation of church from the state, especially the Puritans and some Congregationalists. One result of the wars would be limited religious liberty, but the main legacy was the affirmation of the rights of Parliament—which laid the foundation for the eventual emergence of democratic government by the end of the nineteenth century.

The wars inextricably mingled with and formed part of a linked series of conflicts and civil wars between 1639 and 1651 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, which at that time shared a monarch but formed distinct countries with otherwise separate political structures. Those recent historians who aim to have a unified overview (rather than treating parts of the other conflicts as background to the English Civil War) sometimes call these linked conflicts the “Wars of the Three Kingdoms.” Some have also described them as the “British Civil Wars,” but this terminology can mislead: the three kingdoms did not become a single political entity until the Act of Union of 1800 between the Kingdom of Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) came into effect in 1801.

The wars led to the trial and execution of Charles I, the exile of his son Charles II, and the replacement of the English monarchy with the Commonwealth of England (1649-1653) and then with a Protectorate (1653-1659): the personal rule of Oliver Cromwell. The monopoly of the Church of England on Christian worship in England came to an end, and the victors consolidated the already-established Protestant aristocracy in Ireland. Constitutionally, the wars established a precedent that British monarchs could not govern without the consent of Parliament.

Unlike other civil wars that focused on who ruled, this war also concerned itself with the manner of governing the British Isles. Accordingly, historians also refer to the English Civil War as the “English Revolution” and (especially in seventeenth-century Royalist circles) as the “Great Rebellion.”

Background

Contemporaries must have found it unthinkable that a civil war could result from the events taking place. War broke out less than forty years after the death of the popular Elizabeth I in 1603. At the accession of Charles I, England and Scotland had both experienced relative peace, both internally and in their relations with each other, for as long as anyone could remember. Charles hoped to unite the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland into a new single kingdom, fulfilling the dream of his father, James I of England (James VI of Scotland). Many English Parliamentarians had suspicions regarding such a move, because they feared that setting up a new kingdom might destroy the old English traditions that had bound the English monarchy. As Charles shared his father’s position on the power of the crown (James had described kings as “little gods on Earth,” chosen by God to rule in accordance with the doctrine of the “divine right of kings”), the suspicions of the Parliamentarians had some justification.

Although pious and with little personal ambition, Charles demanded outright loyalty in return for “just rule.” He considered any questioning of his orders as, at best, insulting. This latter trait, and a series of events, seemingly minor on their own, led to a serious break between Charles and his English Parliament, and eventually to war.

Parliament in the English Constitutional Framework

Overview

Before the fighting, the Parliament of England did not have a permanent role in the English system of government, instead functioning as a temporary advisory committee—summoned by the monarch whenever the crown required additional tax revenue, and subject to dissolution by the monarch at any time. Because responsibility for collecting taxes lay in the hands of the landed gentry, the English kings needed the help of that stratum of society in order to ensure the smooth collection of that revenue. If the gentry were to refuse to collect the king’s taxes, he would lack the authority to compel them. Parliaments allowed representatives of the gentry to meet, confer and send policy-proposals to the monarch in the form of Bills. These representatives did not, however, have any means of forcing their will upon the king—except by withholding the financial means he required to execute his plans.

Parliamentary Concerns and the Petition of Right

One of the first events to cause concern about Charles I came with his marriage to a French Roman Catholic princess, Henrietta Maria. The marriage occurred in 1625, shortly after Charles came to the throne. Charles’s marriage made him a possible “Papist” (supporter of papal authority), which gave cause for concern.

Charles also wanted to take part in the conflicts underway in Europe, then immersed in the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). Foreign wars required heavy expenditure, and the crown could raise the necessary taxes only with Parliamentary consent (as described above). Charles experienced even more financial difficulty when his first Parliament refused to follow the tradition of giving him the right to collect customs duties for his entire reign, deciding instead to grant it for only a year at a time.

Charles, meanwhile, pressed ahead with his European wars, deciding to send an expeditionary force to relieve the French Huguenots (Protestants) whom Royal French forces held besieged in La Rochelle. George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, received command of the English force. Unfortunately for Charles and Buckingham, the relief expedition failed—and Parliament opened impeachment proceedings against Buckingham. Charles responded by dissolving Parliament. This move, while saving Buckingham, reinforced the impression that Charles wanted to avoid Parliamentary criticism of his ministers.

Having dissolved Parliament and unable to raise money without it, the king assembled a new one in 1628 (the elected members included Oliver Cromwell). The new Parliament drew up the Petition of Right, and Charles accepted it as a concession in order to get his subsidy. Amongst other things, the petition referred to the Magna Carta.

The Eleven Years’ Tyranny and the Rebellion in Scotland

Overview

Charles I managed to avoid calling a Parliament for the next decade. During this period, Charles’ lack of finances largely determined his policies. Accordingly, his government pursued peaceful policies at home and abroad, and initiated only minimal new legislative activity; Charles preferred to claim that the legitimacy of his personal rule relied on the continuity of ancient customs. His lack of finances caused a number of problems, however. Failure to observe conventions became in some cases a finable offence (for example, a failure to attend and be knighted at Charles’ coronation), while the use of patents and monopolies, and local measures such as demanding payment for illegal houses in London, created ample scope for corruption and led to local discontents.

Charles also tried to raise revenue in the form of “Ship Money.” Exploiting a naval war scare in 1635, he demanded that the inland counties of England pay a tax to support the Royal Navy. This policy relied on established law, but law that had been ignored for centuries, and so was regarded by many as an extra-Parliamentary (and therefore illegal) tax. A number of prominent men refused to pay it on these grounds. Reprisals against William Prynne and John Hampden (fined after losing their case by a vote of seven to five for refusing to pay ship money and for making a stand against the legality of the tax) aroused widespread indignation.

However, Charles aroused the most antagonism through his religious measures. Charles believed in a sacramental version of the Church of England, called High Anglicanism, with a theology based upon Arminianism, a belief shared by his main political advisor, Archbishop William Laud. Laud was appointed by Charles as the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633 and started a series of reforms in the church to make it more ceremonial, starting with the replacement of the wooden communion tables with stone altars.

Puritans accused Laud of trying to reintroduce Catholicism, and when they complained, Laud had them arrested. In 1637 John Bastwick, Henry Burton, and William Prynne had their ears cut off for writing pamphlets attacking Laud’s views—a rare penalty for gentlemen to suffer, and one that aroused anger. Moreover, the statutes passed in the time of Elizabeth I concerning church attendance were revived; Puritans around the country were fined for failure to attend Anglican services.

The end of Charles’ independent governance came when he attempted to apply his religious policies in Scotland. The Church of Scotland, although Episcopalian in structure, had long enjoyed its own independent traditions. Charles, however, wanted one uniform church throughout Britain and introduced a new, High Anglican version of the English Book of Common Prayer into Scotland in the summer of 1637. This met with a violent reaction. A riot broke out in Edinburgh, and in February 1638 the Scots’ objections to royal policy were formulated in the National Covenant. This document took the form of a “loyal protest,” rejecting all innovations that had not first been tested by free parliaments and general assemblies of the church. Before long, Charles was forced to withdraw his Prayer Book and summon a General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, which met in Glasgow in November 1638. The Assembly, affected by the radical mood of the times, not only rejected the Prayer Book, but also went on to take the even more drastic step of declaring the office of bishop as unlawful. Charles demanded the acts of the assembly be withdrawn; the Scots refused to comply, and both sides began to raise armies. Charles accompanied his forces to the border in the spring of 1639 to end the rebellion. After an inconclusive campaign he decided to seek a truce, the Pacification of Berwick. A second Bishops War followed in the summer of 1640. The royal forces in the north were defeated by a Scots army, which went on to capture Newcastle. Charles was eventually forced to agree not only not to interfere with religion in Scotland, but to pay the Scottish war expenses as well.

Local Grievances

In the summer of 1642 these national troubles helped to polarize opinion, ending indecision about which side to support or what action to take. Opposition to Charles also arose owing to many local grievances. For example, the livelihoods of thousands of people were negatively affected by the imposition of drainage schemes in The Fens (Norfolk) after the king awarded a number of drainage contracts. The king was regarded by many as worse than insensitive and this was important in bringing a large part of eastern England into Parliament’s camp. This sentiment brought with it people like the Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester, and Oliver Cromwell, each a notable wartime adversary of the king. Conversely, one of the leading drainage contractors, Robert Bertie, 1st Earl of Lindsey, was to die fighting for the king at the Battle of Edge Hill.

Recall of Parliament

Charles needed to suppress the rebellion in his northern realm. He had insufficient funds, however, and had perforce to seek money from a newly elected Parliament in 1640. The majority faction in the new Parliament, led by John Pym, took this appeal for money as an opportunity to discuss grievances against the crown, and was opposed to an English invasion of Scotland. Charles took exception to this lèse-majesté (offence against the ruler) and dissolved Parliament after only a few days, this earning it the name “the Short Parliament.”

Without Parliament’s support, Charles attacked Scotland again, breaking the truce at Berwick, and suffered a comprehensive defeat. The Scots then seized the opportunity and invaded England, occupying Northumberland and Durham.

Meanwhile, another of Charles’s chief advisers, Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, had risen to the role of Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1632 and brought in much needed revenue for Charles by persuading the Irish Catholic gentry to pay new taxes in return for promised religious concessions. In 1639 Charles recalled him to England, and in 1640 named him Earl of Strafford, attempting to have him work his magic again in Scotland. This time he was not so lucky, and the English forces fled the field in their second encounter with the Scots in 1640. Almost the entirety of Northern England was occupied, and Charles was forced to pay £850 per day to keep the Scots from advancing. If he did not, they would “take” the money by pillaging and burning the cities and towns of Northern England.

All this put Charles in a desperate financial position. As King of Scotland, he was required to find money to pay the Scottish army in England, and as king of England, to find money to pay and equip an English army to defend England. His means of raising revenue without Parliament were critically short of being able to achieve this. It was against this backdrop, and according to advice from the Magnum Concilium (the House of Lords, but without the British House of Commons, so not a Parliament), that Charles finally bowed to pressure and summoned Parliament for November.

The Long Parliament

The new Parliament proved even more hostile to Charles than its predecessor. It immediately began to discuss grievances against Charles and his government, and with Pym and Hampden (of “Ship Money” fame) in the lead, took the opportunity presented by the king’s troubles to force various reforming measures upon him. A law was passed which stated that a new Parliament should convene at least once every three years, without the king’s summons if necessary. Other laws passed by the Parliament made it illegal for the king to impose taxes without Parliamentary consent, and later, gave Parliament control over the king’s ministers. Finally, the Parliament passed a law forbidding the king to dissolve it without its consent, even if the three years were up. Ever since, this Parliament has been known as the “Long Parliament.”

In early 1641 Parliament had Strafford arrested and sent to the Tower of London on a charge of treason. John Pym claimed that Wentworth’s statements of readiness to campaign against “the kingdom” were in fact directed at England itself. The case could not be proven, so the House of Commons, led by Pym and Henry Vane, resorted to a Bill of Attainder. Unlike a guilty finding in a court case, attainder did not require a legal burden of proof, but it did require Royal Assent (the king’s approval). Charles, still incensed over the Commons’ handling of Buckingham, refused. Wentworth himself, hoping to head off the war he saw looming, wrote to the king and asked him to reconsider. Thomas Wentworth was executed in May 1641.[1]

Instead of saving the country from war, Wentworth’s sacrifice in fact doomed it to one. Within months, the Irish Catholics, fearing a resurgence of Protestant power, struck first, and the entire country soon descended into chaos. Rumors circulated that the king supported the Irish, and Puritan members of the Commons were soon agitating that this was the sort of thing that Charles had in store for all of them.

In early January 1642, Charles, accompanied by four hundred soldiers, attempted to arrest five members of the House of Commons on a charge of treason. This attempt failed. When the troops marched into Parliament, Charles asked William Lenthall, the speaker, where the five were. Lenthall replied, “May it please your Majesty, I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place but as the House [of Commons] is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here.” In other words, the speaker proclaimed himself a servant of Parliament, rather than of the king.

The First English Civil War

The “Long Parliament,” having controverted the king’s authority, raised an army led by Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, with the intention of defending Parliament against the king and his supporters. Charles I, in the meantime, had left London and also raised an army using the archaic system of a Commission of Array. He raised the Royal Standard at Nottingham in August.

In September 1642, King Charles I raised his standard in the market square of Wellington, a small (though highly influential) market town in the English Midland county of Shropshire, and addressed his troops the next day at nearby Orleton Hall. He declared that he would uphold the Protestant religion, the laws of England, and the liberty of Parliament.

At the outset of the conflict much of the country remained neutral, but the Royal Navy and most English cities favored Parliament, while the king found considerable support in rural communities. Historians estimate that between them, both sides had only about 15,000 men. However, the war quickly spread and eventually involved every level of society throughout the British Isles. Many areas attempted to remain neutral, some formed bands of clubmen to protect their localities against the worst excesses of the armies of both sides, but most found it impossible to withstand both the king and Parliament. On one side, the king and his supporters thought that they fought for traditional government in church and state. On the other, most supporters of the Parliamentary cause initially took up arms to defend what they thought was the traditional balance of government in church and state which had been undermined by the king. The views of the members of Parliament ranged from unquestioning support of the king (at one point during the First Civil War, there were more members of the Commons and Lords in the King’s Oxford Parliament (1644) than there were at Palace of Westminster) through to radicals, who wanted major reforms in favor of religious independence, including church-state separation, and the redistribution of power at the national level.

The Parliamentary faction which remained in Westminster did, however, have more resources at its disposal, due to its possession of all major cities including the large arsenals at Kingston upon Hull and London. For his part, Charles hoped that quick victories would negate Parliament’s advantage in equipment and supplies. This precipitated the first major siege, the Siege of Hull in July 1642, which provided a decisive victory for Parliament.

The first pitched Battle at Edgehill proved inconclusive, but both the Royalist and Parliamentarian sides claimed it as a victory. A Parliamentarian cavalry troop raised by Oliver Cromwell also played a minor part in the battle. Cromwell would later devise the New Model Army system still evident in military organization today. The New Model featured a unified command structure and professionalism, which would swing the military advantage firmly towards Parliament. The second field action of the war, the standoff at Turnham Green, saw Charles forced to withdraw to Oxford. This city would serve as his base for the remainder of the war.

In general, the early part of the war went well for the Royalists. The turning point came in the late summer and early autumn of 1643, when the Earl of Essex’s army forced the king to raise the siege of Gloucester and then brushed the Royalist army aside at the First Battle of Newbury (September 20, 1643), in order to return triumphantly to London. Other Parliamentarian forces won the Battle of Winceby, giving them control of Lincoln. Political maneuvering on both sides led Charles to negotiate a ceasefire in Ireland, freeing up English troops to fight on the Royalist side, while Parliament offered concessions to the Scots in return for aid and assistance.

With the help of the Scots, Parliament won at Marston Moor in 1644, gaining York and the north of England. Cromwell’s conduct in this battle proved decisive, and demonstrated his potential as a political or military leader. The defeat at the Battle of Lostwithiel in Cornwall, however, marked a serious reverse for Parliament in the southwest of England. Subsequent fighting around Second Battle of Newbury, though tactically indecisive, strategically gave another check to Parliament.

In 1645 Parliament reaffirmed its determination to fight the war to a finish. It passed the Self-denying Ordinance, by which all members of either House of Parliament laid down their commands, and reorganized its main forces into the New Model Army, under the command of Sir Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Baron Fairfax of Cameron, with Cromwell as his second-in-command. In two decisive engagements—the Battles of Naseby on June 14 and Langport on July 10—Charles’s armies were effectively destroyed.

In the remains of his English realm, Charles attempted to recover stability by consolidating the Midlands. He began to form an axis between Oxford and Newark on Trent in Nottinghamshire. Those towns had become fortresses and showed more reliable loyalty to him than to others. He took Leicester, which lies between them, but found his resources exhausted. Having little opportunity to replenish them, in May 1646 he sought shelter with a Scottish army at Southwell in Nottinghamshire. This marked the end of the First English Civil War.

The Second English Civil War

Charles I took advantage of this deflection of attention away from himself to negotiate a new agreement with the Scots, again promising church reform, on December 28, 1647. Although Charles himself remained a prisoner, this agreement led inexorably to the Second Civil War.

A series of Royalist uprisings throughout England and a Scottish invasion occurred in the summer of 1648. Forces loyal to Parliament put down most of the uprisings in England after little more than skirmishes, but uprisings in Kent, Essex and Cumberland, the rebellion in Wales and the Scottish invasion involved the fighting of pitched battles and prolonged sieges.

In the spring of 1648 unpaid Parliamentarian troops in Wales changed sides. Colonel Thomas Horton defeated the Royalist rebels at the battle of St. Fagans (May 8) and the rebel leaders surrendered to Cromwell on July 11 after the protracted two-month siege of Pembroke. Sir Thomas Fairfax defeated a Royalist uprising in Kent at the Battle of Maidstone on June 24. Fairfax, after his success at Maidstone and the pacification of Kent, turned northward to reduce Essex, where under their experienced and popular leader Sir Charles Lucas, the Royalists were in arms in great numbers. Fairfax soon drove the enemy into Colchester, but the first attack on the town was repulsed and he had to settle down to a long siege.

In the north of England, Major-General John Lambert fought a very successful campaign against a number of Royalist uprisings—the largest that of Sir Marmaduke Langdale in Cumberland. Thanks to Lambert’s successes, the Scottish commander, the James Hamilton, 3rd Marquess and 1st Duke of Hamilton, was forced to take the west route through Carlisle for the Royalist Scottish invasion of England. The Parliamentarians under Cromwell engaged the Scots at the Battle of Preston (August 17–August 19). The battle was fought largely at Walton-le-Dale near Preston in Lancashire, and resulted in a victory by the troops of Cromwell over the Royalists and Scots commanded by Hamilton. This Parliamentarian victory marked the end of the Second English Civil War.

Nearly all the Royalists who had fought in the First Civil War had given their parole not to bear arms against the Parliament, and many honorable Royalists, like Jacob Astley, 1st Baron Astley of Reading, refused to break their word by taking any part in the second war. So the victors in the Second Civil War showed little mercy to those who had brought war into the land again. On the evening of the surrender of Colchester, Sir Charles Lucas and Sir George Lisle were shot. The leaders of the Welsh rebels, Major-General Rowland Laugharne, Colonel John Poyer and Colonel Rice Powel (or Powell), were sentenced to death, but Poyer alone was executed on April 25, 1649, being the victim selected by lot. Of five prominent Royalist peers who had fallen into the hands of Parliament, three (the Duke of Hamilton, Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland, and Arthur Capell, 1st Baron Capell) were beheaded at Westminster on March 9.

Trial of Charles I for Treason

The betrayal by Charles caused Parliament to debate whether to return the king to power at all. Those who still supported Charles’s place on the throne tried once more to negotiate with him.

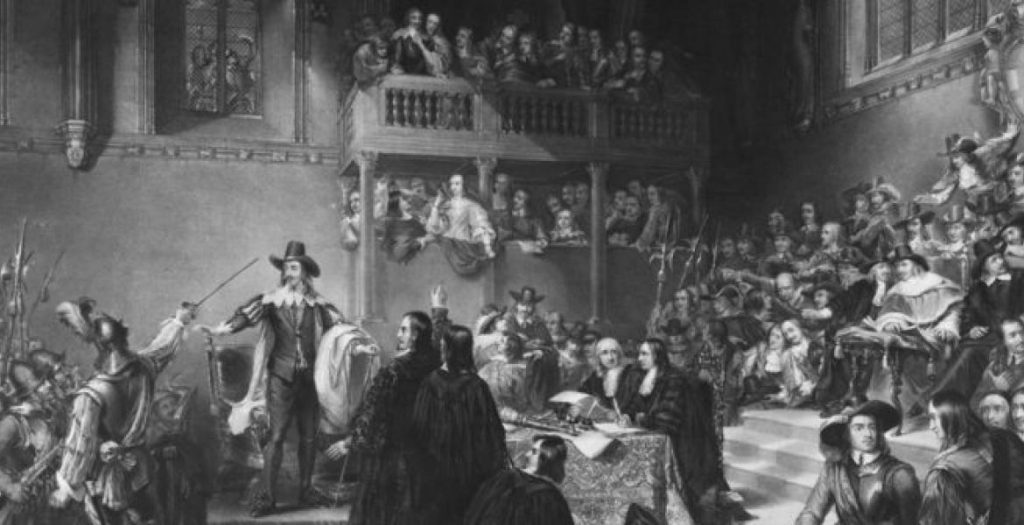

Furious that Parliament continued to countenance Charles as a ruler, the army marched on Parliament and conducted “Pride’s Purge” (named after the commanding officer of the operation, Thomas Pride) in December 1648. Troops arrested 45 members of Parliament and kept 146 out of parliament. Only 75 were allowed in, and then only at the army’s bidding. This Rump Parliament was ordered to set up a high court of justice in order to try Charles I for treason in the name of the people of England.

The trial reached its foregone conclusion. Charles I was found guilty of high treason, as a “tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy.” He was beheaded on a scaffold in front of the Banqueting House of the Palace of Whitehall on January 30, 1649. After the Restoration in 1660, the regicides that were still alive and not living in exile were either executed or sentenced to life imprisonment.

The Third English Civil War

Ireland

Ireland had known continuous war since the rebellion of 1641, with most of the island controlled by the Irish Confederates. Increasingly threatened by the armies of the English Parliament after Charles I’s arrest in 1648, the Confederates signed a treaty of alliance with the English Royalists. The joint Royalist and Confederate forces under James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde, attempted to eliminate the Parliamentary army holding Dublin, but their opponents routed them at the Battle of Rathmines. As the former member of Parliament Admiral Robert Blake blockaded Prince Rupert’s fleet in Kinsale, Cromwell was able to land at Dublin on August 15, 1649, with the army to quell Royalist alliance in Ireland.

Cromwell’s suppression of the Royalists in Ireland during 1649 still has a strong resonance for many Irish people. The massacre of nearly 3,500 people in Drogheda after its capture—comprising around 2,700 Royalist soldiers and all the men in the town carrying arms, including civilians, prisoners, and Catholic priests—is one of the historical memories that has driven Irish-English and Catholic-Protestant strife during the last three centuries. However, the massacre is significant mainly as a symbol of the Irish perception of Cromwell’s cruelty, as far more people died in the subsequent guerrilla and scorched earth fighting in the country than at infamous massacres such as Drogheda and Wexford.

The Parliamentarian conquest of Ireland ground on for another four years until 1653, when the last Irish Confederate and Royalist troops surrendered. It has been estimated that up to 30 percent of Ireland’s population either died or were exiled by the end of the wars. Almost all Irish Catholic owned land was confiscated in the wake of the conquest and distributed to the Parliament’s creditors, to the Parliamentary soldiers who served in Ireland, and to English people who had settled there before the war. Thus began the process by which Protestants were encouraged to colonize Ireland who, though a minority, controlled most of the economy and owned most of the land. In the north, where many Scottish Presbyterians settled, the Protestants became a majority. The legacy would be the Catholic-Protestant “troubles” of the second half of the twentieth century between pro-Republicans (who want a united Ireland) and Unionists (or loyalists who want Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom).

Scotland

The execution of Charles I altered the dynamics of the Scottish Civil War, which had raged between Royalists and Covenanters since 1644. By 1649, the Royalists there were in disarray and their erstwhile leader, the James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, was in exile. At first, Charles II encouraged Montrose to raise a Highland army to fight on the Royalist side. However, when the Scottish Covenanters (who did not agree with the execution of Charles I and who feared for the future of Presbyterianism and Scottish independence under the new Commonwealth) offered him the crown of Scotland, Charles abandoned Montrose to his enemies. However, Montrose, who had raised a mercenary force in Norway, had already landed and was unable to abandon the fight. He was unable to raise many Highland clans and his army was defeated at the Battle of Carbisdale in Ross-shire on April 27, 1650. Montrose was captured shortly afterwards and taken to Edinburgh, where on May 20 he was sentenced to death by the Scottish Parliament and was hanged the next day.

Charles landed in Scotland at Garmouth in Morayshire on June 23, 1650, and signed the 1638 National Covenant and the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant immediately after coming ashore. With his original Scottish Royalist followers and his new Covenanter allies, King Charles II became the greatest threat facing the new English Republic. In response to the threat, Cromwell left some of his lieutenants in Ireland to continue the suppression of the Irish Royalists and returned to England.

He arrived in Scotland on July 22, 1650, and proceeded to lay siege to Edinburgh. By the end of August, disease and a shortage of supplies had reduced the strength of his army and Cromwell was forced to order a retreat towards his base at Dunbar. A Scottish army, assembled under the command of David Leslie, tried to block the retreat, but the Scots were defeated at the Battle of Dunbar on September 3. Cromwell’s army then took Edinburgh, and by the end of the year, his army had occupied much of southern Scotland.

In July 1651, Cromwell’s forces crossed the Firth of Forth into Fife and defeated the Scots at the Battle of Inverkeithing. The New Model Army advanced towards Perth, which allowed Charles, at the head of the Scottish army, to move south into England. Cromwell followed Charles into England, leaving George Monck to finish the campaign in Scotland. Monck took Stirling on August 14 and Dundee on September 1. During the next year, 1652, the remnants of Royalist resistance were mopped up, and under the terms of the “Tender of Union,” the Scots were given 30 seats in a united Parliament in London, with General Monck appointed as the military governor of Scotland.

England

Although Cromwell’s New Model Army had defeated a Scottish army at Dunbar, Cromwell could not prevent Charles II from marching from Scotland deep into England at the head of another Royalist army. The Royalists marched to the west of England because it was in that area that English Royalist sympathies were strongest, but although some English Royalists joined the army, they came in far fewer numbers than Charles and his Scottish supporters had hoped. Cromwell finally engaged the new king at Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651, and defeated him. Charles II escaped, via safe houses&mash;and a famous oak tree—to France, ending the civil wars.

Political Control

During the course of the wars, the Parliamentarians established a number of successive committees to oversee the war effort. The first of these, the “English Committee of Safety,” created in July 1642, was comprised 15 members of Parliament. Following the Anglo-Scottish alliance against the Royalists, the “Committee of Both Kingdoms” replaced the Committee of Safety between 1644 and 1648, when it was dissolved as the alliance ended. The English members of the former Committee for Both Kingdoms continued to meet and became known as the “Derby House Committee.” This in turn was replaced by a second Committee of Safety.

Aftermath

Estimates suggest that around 10 percent of the three kingdoms’ population may have died during the civil wars. As usual in wars of this era, disease caused more deaths than combat did.

The wars left England, Ireland and Scotland as three of the few countries in Europe without a monarch. In the wake of victory, many of the ideals (and many of the idealists) became sidelined. The republican government of the Commonwealth ruled England (and later all of Scotland and Ireland) from 1649 to 1653 and from 1659 to 1660. Between the two periods, and due to in-fighting amongst various factions in Parliament, Oliver Cromwell ruled over the Protectorate as Lord Protector (effectively a military dictator) until his death in 1658.

Upon his death, Oliver Cromwell’s son Richard Cromwell became Lord Protector. But the army had little confidence in him. After seven months, the army removed Richard, and in May 1659 it re-installed the Rump. However, since it acted as though nothing had changed since 1653 and as if it could treat the army as it liked, military force shortly afterwards dissolved this too. After the dissolution of the Rump in October 1659, the prospect of a total descent into anarchy loomed as the army’s pretence of unity finally dissolved into factions.

Into this atmosphere General George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle, governor of Scotland under the Cromwells, marched south with his army from Scotland. On April 4, 1660, in the Declaration of Breda, Charles II made known the conditions of his acceptance of the crown of England. Monck organized the Convention Parliament, which met for the first time on April 25. On May 8 it declared that King Charles II had reigned as the lawful monarch since the execution of Charles I in January 1649. Charles returned from exile on May 23. Later in London, on May 29, the populace acclaimed him as king. His coronation took place at Westminster Abbey on April 23, 1661. These events became known as the English Restoration.

As they resulted in the restoration of the monarchy with the consent of Parliament, the civil wars effectively set England and Scotland on course to adopt a parliamentary form of government. This system would result in the outcome that the United Kingdom, formed under the Acts of Union (1707), would avoid participation in the European republican movements that followed the Jacobin revolution in eighteenth-century France and the later success of Napoleon. Specifically, future monarchs became wary of pushing Parliament too hard, and Parliament effectively chose the line of succession in 1688 with the Glorious Revolution and in the 1701 Act of Settlement 1701. After the restoration, Parliament’s factions became political parties (later becoming the Tory and Whig parties) with competing views and varying abilities to influence the decisions of their monarchs. The United Kingdom became a constitutional monarchy (although the constitution is unwritten).

The rise of the non-conformists, who advocated religious liberty and separation of church and state, led to the Act of Toleration of 1689 that exempted non-conformists from having to attend the Church of England. Catholics and Unitarians were not included. Some civil disabilities remained in place under the Test and Corporations Act (1661), which made local office contingent on, being in good standing with the Church of England (abolished in 1828). The Act of Uniformity of 1662 aimed to re-introduce bishops and the Book of Common Prayer within the Church of England, abandoned by many Puritans during the Commonwealth. Since non-episcopally ordained clergy could no longer serve, many left and established non-conformist congregations.

Theories Relating to the English Civil Wars

Whig View

Whigs explained the Civil War as the result of a centuries-long struggle between Parliament (especially the House of Commons) and the monarchy. Parliament fought to defend the traditional rights of Englishmen, while the monarchy attempted on every occasion to expand its right to dictate law arbitrarily. The most important Whig historian, S.R. Gardiner, popularized the idea of describing the civil war as a “Puritan Revolution” that challenged the repressive nature of the Stuart church and paved the way for the religious toleration of the English Restoration. Puritanism, in this view, became the natural ally of a people seeking to preserve their traditional rights against the arbitrary power of the monarchy.

Marxist View

The Marxist school of thought interpreted the Civil War as a bourgeois revolution. In the words of historian Christopher Hill, “the Civil War was a class war.” On the side of reaction stood the landed aristocracy and its ally, the established church. On the other side stood (again, according to Hill), “the trading and industrial classes in town and countryside, […] the yeomen and progressive gentry, and […] wider masses of the population whenever they were able by free discussion to understand what the struggle was really about.” The Civil War occurred at the point in English history at which the wealthy middle classes, already a powerful force in society, liquidated the outmoded medieval system of English government. Like the Whigs, the Marxists found a place for the role of religion in their account. Puritanism as a moral system ideally suited the bourgeois class, and so the Marxists identified Puritans as inherently bourgeois.

Revisionist and Other Recent Approaches

Beginning in the 1970s, a new generation of historians began mounting challenges to the Marxist and Whig theories. This began with the publication in 1973 of the anthology The Origins of the English Civil War (edited by Conrad Russell). These historians disliked the way that Marxists and Whigs explained the Civil War in terms of long-term trends in English society. The new historians called for and began producing studies which focused on the minute particulars of the years immediately preceding the war, thus returning in some ways to the sort of contingency-based historiography of Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon’s famous contemporary history of the Civil War. As a result, they have demonstrated that the pattern of allegiances in the war did not fit the theories of Whig or Marxist historians. Puritans, for example, did not necessarily ally themselves with Parliamentarians, and many of them did not identify as bourgeois; many bourgeois fought on the side of the king; many landed aristocrats supported Parliament.

The new generation of historians (commonly called “Revisionists”) have discredited large sections of the Whig and Marxist interpretations of the war. Many of these historians (such as Jane Ohlmeyer) have discarded the title “English Civil War” and replaced it with the “Wars of the Three Kingdoms” or even the geographically arguable but politically incorrect “British Civil Wars.” This forms part of a wider trend in British history towards the study of the whole of the British Isles. This trend reacts against what its proponents perceive as “Anglocentric” history, which concentrates on England and ignores or marginalizes other parts of the British Isles. These revisionist historians argue that one cannot fully understand the English Civil War in isolation; it needs to stand as just one conflict in a series of interlocking conflicts throughout the British Isles. They see the causes of the war as a consequence arising from one king, Charles I, ruling over multiple kingdoms. For example, the wars unfolded when Charles I tried to impose an Anglican prayer book on Scotland; when the Scots resisted he declared war on them, but had to raise heavy taxes in England to pay for campaigning, which triggered the Civil War in England.

The Civil War as an American War

The Civil Wars also impacted on the English colonies in the Americas. One result of the wars was an increase in the number of Puritan migrants to America, whose policy of church-state separation and of religious freedom became enshrined in the constitution of the United States. However, just as there were advocates of different forms of “church” in Britain during the Civil War and Commonwealth period, so there were in the American colonies. Some favored Episcopalianism, some Presbyterianism, some Congregationalism. Phillips (2005) records that some Congregationalists held very strong convictions about the war: “hundreds of men from Massachusetts and Connecticut … sailed back to England in the 1640s to fight on the Puritan side against Charles I.” On the other hand, royalist Virginia, where the Episcopalians were strong, “welcomed Cavalier émigrés and expelled its Puritans.” Fighting even broke out within the colonies themselves—in 1655 a battle took place near Annapolis in Maryland between Puritans and Anglican-Catholic forces saw the Puritans win (Phillips 2005, 134). Phillips also points out how the same sides opposed each other during the American Civil War, when many Southern Episcopalians supported slavery and most Northern Congregationalists opposed it; the South tended to see society as hierarchical and the North in more egalitarian terms.

Appendix

Note

- Jacob Abbott Charles I Chapter Downfall of Strafford and Laud

Reference

- Phillips, Kevin. American Theocracy. New York: Viking, 2005.

Originally published by New World Encyclopedia, 10.31.2001, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.