The Neo-Assyrian Empire demonstrates with unusual clarity how internal coercion can move from contingency to structure.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Security, Sovereignty, and the Inward Turn of Force

The history of state power is often narrated outward, through conquest, borders, and war. Yet some of the most revealing evidence of how power actually functioned lies not at the frontier but within the governed space itself. The question of how a state controls its own population, how it enforces obedience once conquest is complete, exposes the deeper mechanics of sovereignty. Internal coercion is not merely a byproduct of imperial rule. In certain political systems, it becomes the central logic of governance.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire offers one of the earliest and most explicit examples of this inward turn of force. From roughly the ninth to the seventh centuries BCE, Assyrian rulers constructed an imperial system in which violence was not confined to moments of rebellion or crisis. Instead, coercion operated continuously through provincial administration. Governors commanded troops permanently stationed within imperial territory, charged with suppressing dissent, relocating populations, and enforcing loyalty through exemplary punishment. These practices were neither hidden nor regretted. They were proclaimed, depicted, and celebrated as the foundation of order.

Crucially, Neo-Assyrian internal force did not rest on emergency authorization or temporary suspension of norms. There was no conceptual divide between normal governance and extraordinary repression. Authority flowed directly from the king, whose will functioned as the ultimate source of law. Violence required no procedural justification beyond loyalty to the ruler and the maintenance of security. In this system, legality did not constrain coercion. It affirmed it. The administrative use of terror was therefore not a failure of law but an expression of how law itself was understood.

What follows argues that the Neo-Assyrian Empire represents a formative moment in the history of internal policing, one in which routine coercion became a permanent administrative function rather than an exceptional response. By examining provincial governance, military deployment within imperial space, and the ideological celebration of violence in inscriptions and reliefs, the analysis demonstrates how security logic displaced legal restraint. In doing so, it reveals an early model of state power in which order was sustained not by consent or codified limitation, but by the normalization of force turned inward.

Empire as an Internal System: Beyond Conquest Narratives

Histories of the Neo-Assyrian Empire have long privileged motion over maintenance. Campaigns, sieges, and battlefield victories dominate both ancient royal inscriptions and modern scholarship. This emphasis creates the impression of an empire perpetually expanding outward, defined primarily by its enemies beyond the frontier. Yet conquest alone does not explain how Assyria ruled, nor how it sustained control over territories long after armies moved on.

Once expansion slowed, the empire faced a more difficult and enduring problem: governing populations already incorporated into imperial space. By the ninth century BCE, Assyria presided over an immense and culturally heterogeneous domain, stretching across Mesopotamia and into the Levant. These lands were not governed indirectly through client kings alone but reorganized into provinces administered by Assyrian officials. Roads, relay stations, taxation systems, and garrisons knit these regions into a centralized structure. The result was not a loose imperial perimeter but an internally coherent political system in which distance from the capital did not imply autonomy. Governance, not conquest, became the dominant challenge.

Within this framework, stability could not be assumed. Diversity of language, cult, and political tradition meant that loyalty had to be continually enforced rather than passively expected. The Assyrian response was to embed coercive power directly into provincial administration. Military units were stationed permanently within provinces, not as occupying forces awaiting withdrawal but as instruments of everyday rule. Their presence signaled that imperial authority was continuous and immediate, capable of intervention at any moment.

The empire functioned less as a series of conquered zones than as a monitored internal landscape. Violence was not reserved for rebellion; it underwrote governance itself.

Provincial Governors and the Militarization of Administration

At the core of Neo-Assyrian provincial rule stood the governor, a figure whose authority deliberately collapsed distinctions that later political systems would come to treat as foundational. He was not simply a civil administrator charged with overseeing taxation, infrastructure, or agricultural output. Nor was he merely a military officer responsible for local defense. Instead, the governor embodied a fusion of administrative, judicial, and coercive power, operating as the direct and unmediated representative of the king within provincial space. This concentration of authority was neither incidental nor transitional. It reflected a conscious imperial design in which governance itself was inseparable from the capacity to apply force. The governor did not govern alongside coercion. He governed through it.

Provincial governors were appointed by the king and answered to him alone. Their responsibilities extended across civil administration, economic extraction, and security enforcement, but these domains were never institutionally separated. Governors commanded troops stationed permanently within their provinces, forces that did not await rebellion to act but existed as an ever-present instrument of control. Unlike temporary garrisons deployed during campaigns, these units formed part of the administrative infrastructure. Military force, in this context, was not an auxiliary to governance. It was one of its defining tools.

The presence of troops under gubernatorial command reshaped the nature of provincial authority. Decisions concerning taxation, population movement, or punishment could be enforced immediately and violently, without appeal to external institutions. Governors possessed the capacity to act preemptively against perceived threats, whether those threats were real, anticipated, or symbolically constructed. The absence of procedural constraints meant that judgment and enforcement collapsed into a single moment of action.

This fusion of administration and militarization also altered relationships between center and periphery. The king did not need to intervene constantly or issue special mandates. By delegating coercive authority downward, the state embedded royal power into the daily life of the provinces. Governors functioned as extensions of the monarch’s will, translating imperial ideology into localized enforcement. The result was a system in which obedience was not negotiated through law or custom but secured through proximity to force.

Militarized administration thus became normal rather than exceptional. Provincial governance operated on the assumption that coercion was always available, always legitimate, and always justified by the need for security. In such a system, political order did not emerge from stability. Stability emerged from the continual readiness to punish.

Terror as Policy: Deportation, Punishment, and Public Display

Violence within the Neo-Assyrian Empire was not improvised, episodic, or confined to moments of crisis. It followed recognizable patterns, repeated across reigns and provinces, and was embedded within the everyday machinery of administration. Deportation, corporal punishment, execution, and mutilation were deployed systematically against populations deemed disloyal or unreliable, not as breakdowns of order but as instruments designed to produce it. These measures were recorded, categorized, and justified within official discourse, indicating a high degree of institutional normalization. Violence, in this sense, functioned as a predictable administrative response rather than an exceptional deviation from governance.

Among these tools, mass deportation occupied a central place. Entire communities were uprooted and relocated across vast distances, often broken apart and resettled among foreign populations. This practice served multiple purposes simultaneously. It disrupted local power structures, severed ties to land and kinship networks, and supplied labor to other regions of the empire. Deportation was thus both punitive and productive. Its effectiveness lay not only in the suffering it inflicted but in the message it conveyed: collective identity itself was contingent on obedience to imperial authority.

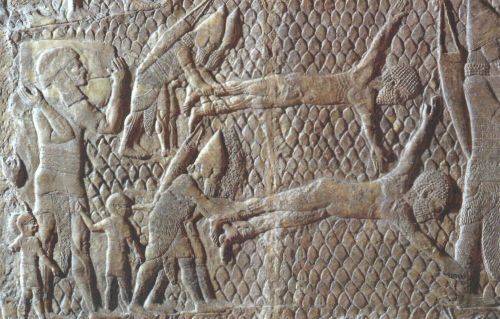

Punishment operated with similar intentionality and ideological clarity. Assyrian sources describe executions, flaying, impalement, and dismemberment with striking specificity, often lingering on bodily detail. These descriptions were not incidental. They framed violence as a morally ordered act carried out by a ruler restoring equilibrium between divine mandate and political obedience. The severity of punishment was calibrated not to legal procedure or proportionality but to symbolic resonance. By transforming the punished body into a site of meaning, the state converted individual suffering into a lesson for the wider population, reinforcing the association between disloyalty and annihilation.

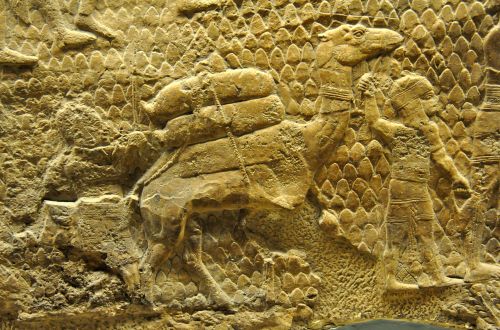

Public display transformed violence into communication. Executions were staged, bodies displayed, and reliefs carved to preserve these scenes in stone. Palace walls depicted subdued enemies, punished rebels, and rows of captives led away from their homes. These images were not aimed at distant audiences alone. They confronted officials, elites, and visitors within the heart of imperial space. Violence was rendered permanent, its memory reinforced through repetition and monumentality.

Deportation, punishment, and public display constituted a coherent policy rather than a collection of excesses. Terror functioned as a language of rule, legible to both administrators and subjects, shaping expectations long before coercion needed to be applied again. By making the consequences of disobedience unmistakable and omnipresent, the Neo-Assyrian state reduced the need for continual intervention. Order was sustained not through trust, negotiation, or legal predictability, but through the routinization of fear as a governing principle embedded in the administrative fabric of empire.

Law without Limitation: Authority Flowing from the King’s Will

The Neo-Assyrian Empire possessed law, but it did not possess law as limitation. Legal texts, administrative orders, and judicial practices existed, yet none functioned as a barrier separating sovereign authority from coercive action. Law articulated hierarchy and obligation, but it did not restrain power once royal will was engaged. Legality, in this system, served governance rather than constrained it.

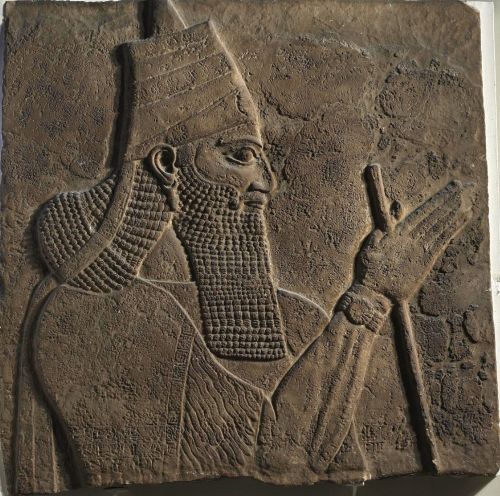

Royal authority stood at the center of this legal universe. The Assyrian king was not merely the highest judicial authority. He was the source from which law derived its meaning and force. Loyalty to the king was inseparable from obedience to law, and disloyalty constituted not simply political resistance but moral transgression. Punishment did not require formal adjudication beyond the assertion that the king’s order had been violated. This fusion of sovereignty and legality ensured that coercion always carried the appearance of legitimacy, even when it was arbitrary or extreme.

Provincial governance reflected this structure with particular clarity. Governors and officials exercised punitive authority without reference to codified limits or standardized procedures. There were no institutional mechanisms through which subjects could appeal decisions or contest enforcement. Judgment and execution collapsed into a single act, carried out in the name of royal authority. Law thus operated retrospectively, validating actions already taken rather than regulating behavior in advance. Violence did not signal the failure of the legal order. It was one of the primary ways that legal order was made visible and effective.

The result was a political system in which authority flowed uninterrupted from the king’s will to the moment of coercion. Without formal boundaries separating law from force, there was no conceptual space for restraint. Security and legality reinforced one another rather than standing in tension. By defining coercive action as inherently lawful when enacted under royal authority, the Neo-Assyrian state normalized internal violence as a permanent condition of governance, embedding force into the everyday operation of rule rather than reserving it for moments of crisis.

Celebrating Violence: Inscriptions, Reliefs, and Imperial Messaging

Neo-Assyrian violence was not merely enacted. It was curated, recorded, and displayed. Royal inscriptions and palace reliefs formed a deliberate communicative system through which coercion was transformed into ideology. These media did not document violence as an unfortunate necessity of rule. They presented it as a moral and political achievement, integral to the maintenance of order. By embedding violence into the visual and textual landscape of empire, the state ensured that its logic was continually rehearsed and reaffirmed.

Royal inscriptions provide the clearest articulation of this ideology. Kings described punitive campaigns, executions, and deportations in formulaic yet vivid language, often emphasizing the scale and severity of punishment. These texts were not private records. They were meant to be read aloud, copied, and displayed, reinforcing a shared understanding of imperial authority. Violence was framed as righteous, proportionate, and divinely sanctioned, even when directed against populations already incorporated into the empire. Inscriptions thus functioned as normative statements, defining what constituted legitimate rule and acceptable enforcement.

Reliefs extended this messaging into visual form. Palace walls depicted scenes of punishment, submission, and suffering with meticulous detail. Captives were shown bound, mutilated, or marched into exile, their humiliation rendered permanent in stone. These images were not peripheral decoration. They structured the spaces through which officials and visitors moved, confronting viewers with an unambiguous hierarchy of power. Violence became spatial as well as symbolic, shaping the experience of imperial authority through constant visual encounter.

The intended audience for these displays was broad but carefully stratified. Provincial elites, administrators, military officers, foreign envoys, and Assyrian officials themselves were all meant to internalize the message encoded in text and image. The reliefs and inscriptions did not function solely as threats directed outward at subject populations. They also disciplined those who governed in the king’s name, reinforcing expectations of loyalty, competence, and severity. By repeatedly exposing officials to images of punishment and submission, the state cultivated a shared political culture in which coercion was normalized and anticipated. Imperial messaging thus worked inward as much as outward, shaping how authority was understood, exercised, and reproduced across the administrative hierarchy.

In the Neo-Assyrian Empire, celebrating violence was a mechanism of stability rather than spectacle alone. By monumentalizing coercion, the state normalized it, integrating punishment into the symbolic order of governance. Violence did not need to be constantly enacted to remain effective. Its images and words persisted, shaping behavior through anticipation and memory. In this way, imperial messaging ensured that terror functioned as a continuous presence, sustaining order long after the immediate act had passed.

Security as Administration: The Normalization of Internal Coercion

By the height of Neo-Assyrian power, security was no longer conceived as a response to disruption or disorder. It had become a permanent administrative condition, woven into the daily operations of governance. Coercive capacity was not mobilized only when resistance emerged; it was embedded structurally into provincial life. Troops stationed within imperial territory, governors endowed with broad punitive authority, and dense systems of surveillance and reporting ensured that enforcement was continuous rather than episodic. The presence of force did not signal crisis. It signaled normality. Order was not restored after being broken. It was imposed in advance through the constant visibility of power.

This administrative conception of security altered the relationship between ruler and subject in fundamental ways. Subjects were not protected by law so much as managed through the anticipation of force. Loyalty was assumed only insofar as it was continually demonstrated, and deviation was met not with investigation or negotiation but with immediate correction. In this environment, obedience was less a legal obligation than a survival strategy. Security logic reclassified ordinary civic life as a potential site of threat, justifying intervention without the need for extraordinary circumstances.

The normalization of internal coercion also reshaped institutional behavior. Officials governed with the expectation that violence was always available and always legitimate. This expectation reduced uncertainty within the administrative hierarchy while increasing it for the population at large. Predictability existed only in one direction. Subjects could predict punishment, but not restraint. The absence of formal limits on enforcement meant that security decisions were discretionary, shaped by local conditions and personal judgment rather than standardized procedure. Administration thus operated through a constant readiness to punish rather than a stable framework of rules.

In the Neo-Assyrian Empire, security became indistinguishable from governance itself. The state did not wait for crisis to justify coercion. It treated coercion as the foundation upon which order rested. By transforming internal force into an ordinary administrative tool, Assyrian rule demonstrated how legality could coexist with, and even reinforce, routine violence. The result was a durable but brittle system, stable so long as fear remained effective, and fragile once its coercive logic began to falter.

Conclusion: When Order Is Built on Permanent Force

The Neo-Assyrian Empire demonstrates with unusual clarity how internal coercion can move from contingency to structure. Violence was not a failure of governance nor a temporary deviation justified by crisis. It was an organizing principle embedded in administration, law, and ideology. Provincial terror functioned as a routine instrument of rule, sustained by the fusion of military power with civil authority and by a legal culture that located legitimacy in royal will rather than procedural restraint.

By normalizing coercion, the Assyrian state resolved one problem while creating another. Permanent force produced predictability for officials and obedience among subjects, but it did so at the cost of institutional adaptability. Governance became dependent on fear as a stabilizing mechanism rather than on shared norms, negotiated authority, or procedural consistency. As a result, political order required constant reinforcement through the visible readiness to punish. This dependence narrowed the range of acceptable responses to dissent and left little room for accommodation or reform. Stability endured only so long as coercive credibility remained intact.

This model exposes a fundamental tension within early state power that extends beyond Assyria itself. Security achieved through administrative violence is efficient, immediate, and legible, yet it corrodes the conceptual boundary between law and force that allows governance to regulate itself. In the absence of limitation, legality ceases to operate as a check on authority and instead becomes a language through which domination is expressed. Law does not disappear. It persists as affirmation rather than restraint, endorsing action after the fact rather than shaping it in advance. The Assyrian case thus reveals a system that is not lawless, but one in which law has been fully absorbed into the logic of coercion.

Seen in this light, the Neo-Assyrian Empire is not merely an ancient anomaly but a foundational example of how states can internalize coercion as administration. Its history shows that when order is built on permanent force, stability is achieved through compression rather than consent. The result is a political system capable of extraordinary durability, yet inherently fragile once fear no longer suffices to hold it together.

Bibliography

- Aster, Shawn Zelig. “Assyrian “Control Points” in the Domination of the Southern Levant in the Reign of Tiglath-Pileser III.” Aula Orientalis 39:1 (2021): 47-55.

- Bahrani, Zainab. The Graven Image: Representation in Babylonia and Assyria. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

- —-. Rituals of War: The Body and Violence in Mesopotamia. New York: Zone Books, 2008.

- Bedford, Peter R. Empire and Exploitation: The Neo-Assyrian Empire. Social Science History Institute, Stanford University, 2001.

- Collins, Paul. “Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Violence: Warfare in Neo-Assyrian Art.” In Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art, Brian A. Brown and Marian H. Feldman (eds). London: Brill (2013): 619-644.

- Garfinkle, Steven J. “Ancient Near Easter City-States.” In The Oxford Handbook of the State in the Ancient Near East, edited by Peter F. Bang and Walter Scheidel, 419–444. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Grayson, A. Kirk. Assyrian Rulers 3rd and 2nd Millenia BC (to 1115 BC). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987.

- Liverani, Mario. The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. London: Routledge, 2013.

- —-. Assyria: The Imperial Mission. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2017.

- —-. Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Parker, Bradly J. “Toward an Understanding of Borderland Processes.” American Antiquity 71:1 (2006): 77–100.

- Postgate, J. Nicholas. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London: Routledge, 1994.

- —-. The Land of Assur and the Yoke of Assur. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Radner, Karen. Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- —-. “Royal Decision-Making: Kings, Magnates, and Scholars.” In The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, edited by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson, 412–430. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Radner, Karen, and Eleanor Robson, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Russell, John Malcolm. The Writing on the Wall: Studies in the Architectural Context of Late Assyrian Palace Inscriptions. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1999.

- Seymour, Michael. “The Empire in the Palace: Campaign Reliefs in the Southwest Palace at Nineveh and an Assyrian Microcosm.” In Assyria to Iberia: Art and Culture in the Iron Age, edited by Joan Aruz et al., 211–223. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016.

- van de Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

- —-. King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005.

- Wells, Bruce, Cornelia Wunsch, and F. Rachel Magdalene. Fault, Responsibility, and Administrative Law in Late Babylonian Legal Texts. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2019.

- Westbrook, Raymond. A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

- Winter, Irene J. “Royal Rhetoric and the Development of Historical Narrative in Neo-Assyrian Reliefs.” Studies in Visual Communication 7:2 (1981): 2–38.

- Zaia, Shana. “Kings, Priests, and Power in the Neo-Assyrian Period.” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 19 (2019): 152-169.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.26.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.