Print culture ultimately demonstrated that repetition is not the opposite of thought, but one of its enabling conditions.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Text Became Too Available

The invention of movable-type printing in mid-fifteenth-century Europe transformed the material conditions of knowledge with extraordinary speed. Text, once scarce, laborious, and expensive to reproduce, suddenly became replicable at scale. Manuscript culture had limited circulation through cost, training, and institutional control. Print shattered those constraints. Books, pamphlets, sermons, indulgences, calendars, romances, and political tracts poured into cities and towns, reaching audiences previously excluded from sustained textual engagement. The problem was not simply that more people could read, but that more people could publish, copy, and circulate ideas with unprecedented ease.

This sudden availability provoked anxiety almost immediately. Humanists, clerics, and scholars recognized that the authority of texts had rested in part on their rarity. Scarcity functioned as a filter. It slowed transmission, reinforced hierarchy, and conferred prestige on those who controlled copying and interpretation. Print removed that friction. Texts no longer bore the marks of institutional endorsement by default. Anyone with access to a press could reproduce scripture, commentary, satire, or polemic. The traditional alignment between learning, legitimacy, and limited circulation began to unravel.

Critics of early print culture did not object primarily to literacy itself. They worried about saturation. The flood of cheap texts threatened to drown careful scholarship in formulaic repetition and polemical excess. Pamphlets recycled arguments rapidly. Sermons echoed sermons. Devotional works multiplied with minimal variation. Readers, it was feared, would skim rather than study, accumulate rather than understand. Authority, once anchored in slow transmission and elite mediation, appeared to dissolve into noise. Cultural abundance raised the specter of intellectual flattening.

What follows argues that early modern anxiety about print was not a reactionary misunderstanding of progress, but a historically predictable response to sudden abundance. When access expands faster than evaluative institutions can adapt, meaning feels endangered, not because it has vanished, but because its traditional markers no longer function reliably. Print disrupted inherited systems of trust before new ones had time to form. Yet history suggests that such moments are transitional rather than terminal. The same printing press that produced floods of cheap, repetitive text would later sustain peer review, standardized scholarship, scientific replication, and mass literacy. Early fears were not wrong in identifying disorientation and noise, but they were incomplete in their assessment of cultural resilience. Print did not destroy authority or originality. It dislodged them from scarcity and forced societies to rebuild standards of judgment under conditions of scale.

Before Print: Scarcity, Authority, and Intellectual Control

Before the advent of print, European intellectual life was structured around scarcity. Texts were expensive to produce, slow to copy, and limited in circulation. Manuscripts required skilled labor, specialized materials, and institutional backing, most often from monasteries, cathedral schools, or universities. These material constraints functioned not merely as logistical limits but as cultural filters. Knowledge moved slowly, and slowness itself became a guarantor of seriousness. Authority was inseparable from the conditions of transmission.

Scarcity reinforced hierarchy in both visible and subtle ways. Access to books signaled membership in a narrow intellectual elite trained in Latin literacy, theological interpretation, and scholastic method. The limited number of texts ensured that reading remained embedded within institutions capable of regulating meaning and enforcing orthodoxy. Universities controlled curricula and degrees. Clerical authorities oversaw doctrine and sanctioned interpretation. Commentary traditions developed cautiously, anchored to authoritative texts whose legitimacy was reinforced by endurance, repetition, and careful transmission. Innovation occurred, but within tightly bounded frameworks that preserved continuity and institutional control.

Manuscript culture also tied intellectual authority to physical proximity and personal networks. Scholars encountered texts through teachers, libraries, and scriptoria rather than open markets. Transmission depended on trust in scribes, patrons, and institutional custodians, not on abstract notions of authorship or intellectual property. Errors and variations certainly existed, but they propagated slowly and visibly, allowing correction through communal scrutiny. The physicality of manuscripts made the history of a text legible. Marginalia, corrections, and layers of commentary recorded interpretive lineage, reinforcing the sense that knowledge was inherited, not improvised.

This system produced stability at the cost of exclusion. Scarcity limited intellectual participation, ensuring that learning remained concentrated among clerical and academic elites. Yet this limitation also preserved coherence. Fewer texts meant fewer competing claims to authority. Disagreement unfolded within shared frameworks, using common sources and recognized methods. Even conflict reinforced consensus by occurring within a bounded intellectual world. The difficulty of accessing texts reinforced reverence for them. Books carried weight because they were rare, labor-intensive, and socially guarded.

The arrival of print would dismantle these conditions with startling speed, but it is crucial to recognize what was lost alongside what was gained. Manuscript culture sustained authority by embedding knowledge within institutions that controlled reproduction, circulation, and interpretation. Scarcity was not incidental to this system. It was foundational. When print removed scarcity, it did not merely accelerate transmission or broaden access. It destabilized the mechanisms through which intellectual control had been exercised for centuries. Early modern Europe was suddenly confronted with a problem it had never faced before: how to preserve authority, coherence, and trust when texts could circulate independently of the institutions that once governed them.

The Explosion of Print: Pamphlets, Tracts, and Cheap Authority

International Printing Museum, Wikimedia Commons

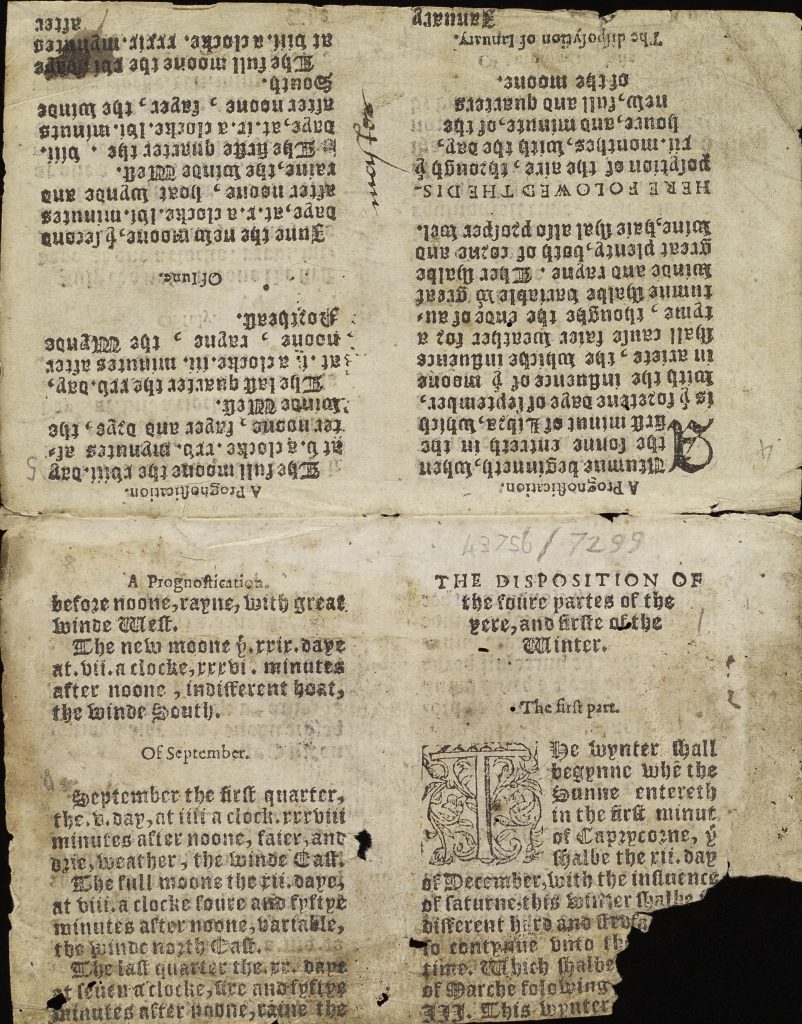

The introduction of print did not simply increase the number of books in circulation. It transformed the tempo, scale, and social reach of textual production. By the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, presses across Europe were producing pamphlets, broadsheets, sermons, indulgences, romances, calendars, and polemical tracts at a pace unimaginable in manuscript culture. These texts were small, cheap, portable, and disposable. They traveled quickly through cities, marketplaces, taverns, and churches, reaching readers who had never before owned or regularly handled written material. Print democratized access not only to reading, but to authorship itself.

Pamphlets became the emblematic genre of this new textual economy. Short, topical, and formulaic, they responded rapidly to political events, religious disputes, and social anxieties. Arguments were recycled with minor variations, titles echoed one another, and familiar rhetorical strategies were reused to capture attention. Speed mattered more than originality. What counted was circulation, not endurance. For contemporaries accustomed to the slow authority of manuscript transmission, this torrent of near-duplicate texts felt destabilizing. The press appeared to reward repetition over reflection and immediacy over depth.

Religious controversy magnified these effects dramatically. The Reformation unfolded as a print phenomenon as much as a theological one. Sermons, catechisms, vernacular Bibles, polemical cartoons, hymns, and doctrinal pamphlets flooded the public sphere in unprecedented volume. Competing interpretations of scripture circulated simultaneously, each claiming legitimacy and urgency. Print stripped religious authority of its traditional bottlenecks. Clerical mediation was no longer required for access to sacred texts, nor for the publication of interpretation. For critics, this proliferation threatened doctrinal coherence and ecclesiastical control. The fear was not simply schism, but saturation: that repetition and polemic would replace disciplined exegesis with partisan noise, making truth harder to recognize precisely because it was everywhere contested.

The vernacularization of print further intensified anxiety by dismantling linguistic gatekeeping. Latin had long served as a filter that limited participation to trained elites and slowed interpretive drift. Print accelerated the spread of vernacular texts, expanding readership while unsettling intellectual hierarchies. Popular romances, almanacs, devotional manuals, and instructional tracts adopted repetitive structures and familiar tropes designed for rapid comprehension and broad appeal. Critics lamented what they perceived as vulgarization: the displacement of learned argument by simplified formulas and moral commonplaces. The concern was not merely that texts were repetitive, but that readers were being trained to expect ease, familiarity, and emotional immediacy rather than sustained engagement. Repetition became pedagogical, shaping habits of reading as much as content.

Economic incentives reinforced these patterns with remarkable speed. Printers and publishers operated in competitive markets with thin margins and high risk. Familiar formats sold reliably. Repetition reduced uncertainty. Pamphlets that echoed successful models could be produced quickly, marketed efficiently, and discarded without consequence. Authority, once grounded in institutional endorsement and slow accumulation of credibility, began to shift toward visibility and circulation. Influence was measured by reach rather than authorization. For contemporaries steeped in manuscript norms, this inversion was alarming. Intellectual value appeared to follow demand rather than deliberation, popularity rather than proof. Cheap authority seemed to erode the distinction between knowledge and persuasion.

The chaos of early print culture was not accidental or pathological. It was transitional. The explosion of cheap text revealed a mismatch between inherited systems of authority and new conditions of abundance. Print did not immediately produce clarity or coherence. It produced noise, redundancy, and conflict. But this noise was the raw material from which new filters, genres, and standards would eventually emerge. The pamphlet flood was not the end of authority. It was the beginning of its reconfiguration under conditions of scale.

The Anxiety of Mediocrity: “Anyone Can Publish”

As print spread across early modern Europe, critics increasingly framed their unease in terms of quality rather than sheer quantity. The problem was no longer simply that texts were abundant, but that the mechanisms for distinguishing excellence from mediocrity appeared to be dissolving. Humanists and scholars complained that the press empowered writers without training, discipline, or intellectual lineage. The fear was not illiteracy but cultural leveling: a world in which repetition, simplification, and rhetorical excess crowded out careful argument and learned refinement. Print seemed to flatten distinctions that had once separated scholarship from persuasion, authority from visibility, and mastery from mere participation.

This anxiety was closely tied to the erosion of elite gatekeeping. In manuscript culture, publication was inseparable from institutional approval, patronage, or clerical oversight. Print severed that link with remarkable speed. Anyone with sufficient capital, access to a press, or a willing printer could circulate ideas widely and anonymously. For established scholars, this represented a collapse of intellectual hierarchy. Authority no longer flowed automatically from education, institutional position, or lineage, but increasingly from circulation and demand. Critics worried that popularity had become a proxy for truth, and that ease of reproduction encouraged imitation rather than rigor.

The figure of the untrained author haunted early modern commentary on print. Satirical attacks portrayed pamphleteers as hacks, recycling arguments without understanding them and chasing attention rather than truth. The press, it was argued, rewarded speed over substance and familiarity over originality. Repetition was not merely aesthetic but epistemic, training readers to accept formulaic claims as knowledge. The anxiety here closely mirrors later fears of mass culture: that the lowest common denominator would dominate, and that serious thought would be submerged beneath layers of shallow production.

This fear of mediocrity also reveals an unresolved tension at the heart of print culture. Print did not create poor writing or shallow argument. It exposed it. By lowering barriers to publication, the press made visible the full range of intellectual output, not just the elite portion previously preserved by scarcity. What appeared to some as decline was often a recalibration of perspective. Authority could no longer hide behind limited access. It had to be earned through argument, evidence, durability, and response. The anxiety that “anyone can publish” thus marked not the death of intellectual standards, but the moment when standards could no longer rely on exclusion alone and had to justify themselves in public view.

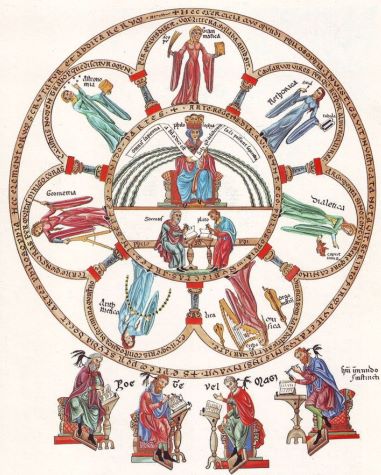

Formula, Repetition, and the Fear of Shallow Reading

Alongside concerns about authorship and authority, early critics of print worried deeply about how people were reading and what reading was becoming. The abundance of cheap, repetitive texts appeared to encourage speed rather than deliberation, accumulation rather than comprehension. Almanacs, catechisms, devotional manuals, and romances relied on familiar structures and recurring phrases designed for quick recognition and easy retention. To critics trained in scholastic or humanist traditions, this shift felt profoundly unsettling. Reading was no longer anchored to slow interpretation guided by teachers, glosses, and disputation. It risked becoming a solitary, unsupervised activity oriented toward consumption rather than understanding, repetition rather than inquiry.

Formula lay at the center of this fear. Repetition made texts legible to wider audiences, but it also seemed to flatten intellectual effort. Readers learned what to expect and how to respond without sustained engagement. Moral lessons arrived prepackaged. Arguments were condensed into slogans. Religious instruction relied increasingly on memorization rather than dialectical exploration. Critics worried that such reading habits trained passivity, encouraging assent without analysis and recognition without reflection. The press, in this view, was not merely reproducing texts mechanically. It was reshaping cognition itself by habituating readers to ease, familiarity, and rapid gratification.

These anxieties reflected older assumptions about what serious reading required. In manuscript culture, scarcity enforced attention. Texts were few, difficult to access, and embedded within pedagogical structures that emphasized commentary, disputation, and close reading. Print disrupted these conditions abruptly. Readers encountered texts outside institutional supervision and in overwhelming quantity. The fear was not simply misunderstanding, but the erosion of expectation. If reading no longer demanded effort, would readers still seek depth at all.

The critique of formula revealed an incomplete understanding of how reading practices evolve under conditions of abundance. Repetition did not eliminate depth. It redistributed it. Familiar genres and recurring forms reduced the cognitive burden of decoding, freeing attention for comparison, evaluation, and synthesis across texts. Over time, readers learned to navigate volume rather than be overwhelmed by it. New habits of annotation, indexing, excerpting, and cross-referencing emerged precisely to manage scale. What initially appeared as intellectual decline was often a transitional phase in the development of mass literacy. Formula and repetition were not the enemies of meaning. They were the scaffolding through which new forms of reading, judgment, and critical engagement would eventually mature.

Authority Reconfigured: New Filters Emerge

The destabilization of traditional authority produced by print did not result in permanent chaos. Instead, it forced the gradual emergence of new mechanisms for evaluating credibility, quality, and trust. As manuscript-era gatekeeping collapsed, early modern Europe began to experiment with alternative filters capable of operating at scale. Authority was not abolished. It was redistributed. The problem was no longer how to restrict access to texts, but how to sort, rank, and evaluate an ever-growing body of material.

One of the earliest responses came from within the print trade itself. Printers, publishers, and booksellers became informal arbiters of quality through branding, reputation, and specialization. Imprints, title pages, typefaces, and even paper quality began to function as signals of reliability. Readers learned to associate certain presses with accuracy, orthodoxy, or intellectual seriousness, while others acquired reputations for haste, error, or sensationalism. Errors, pirated editions, and poorly produced texts damaged credibility and sales. Over time, market pressures rewarded consistency, care, and editorial discipline, even as they encouraged popular appeal. Authority thus began to attach not only to authors or institutions, but to the material and commercial practices of production itself.

Scholarly institutions adapted as well. Universities, academies, and learned societies responded to print abundance by formalizing standards of evidence, citation, and review. The emergence of scientific societies in the seventeenth century marked a decisive shift. Knowledge claims were increasingly evaluated through collective scrutiny rather than personal authority or inherited reputation. Journals and proceedings introduced periodic publication cycles that filtered novelty through peer assessment. Print, once feared as a vector of mediocrity, became the infrastructure through which disciplined inquiry, replication, and debate were coordinated across distance and time.

Libraries and bibliographic tools further reshaped authority by enabling navigation rather than exclusion. Catalogs, indices, encyclopedias, florilegia, and reference works proliferated in response to textual abundance. Instead of suppressing texts, institutions sought to organize them. Classification systems imposed order on volume, allowing readers to situate works within intellectual lineages, disciplines, and debates. Techniques of excerpting, cross-referencing, and indexing trained readers to move comparatively across texts rather than submit to any single one. Authority increasingly depended on context and relational positioning. Meaning was constructed through comparison, citation, and accumulation rather than guaranteed by scarcity.

Censorship and licensing regimes also played a role, though often unevenly and contentiously. States and churches attempted to reassert control through permissions, bans, indexes of prohibited books, and licensing systems. These efforts rarely eliminated unwanted material and often lagged behind production itself. In many cases, censorship amplified visibility rather than suppressing it, drawing attention to contested works and ideas. Still, these mechanisms mattered symbolically. They marked boundaries, signaled anxiety, and articulated claims about legitimate knowledge. Authority in the age of print thus emerged not from a single institution, but from a shifting constellation of filters—economic, scholarly, bureaucratic, and social—designed to make meaning survivable under conditions of scale.

The Long Transition: Chaos before Coherence

The reconfiguration of authority in the age of print was neither swift nor orderly. Early modern Europe experienced a prolonged period of instability in which inherited systems of judgment lagged behind the speed and volume of textual production. Print expanded faster than institutions could adapt, producing a sense of disorder that contemporaries often interpreted as decline. Conflicting voices competed for attention, standards varied widely, and readers confronted a landscape crowded with claims that could not easily be reconciled. The problem was not that coherence disappeared, but that it had not yet learned how to operate at scale.

This transitional chaos was intensified by uneven literacy, access, and interpretive training. New readers entered the textual public without shared norms for evaluation, while established elites struggled to assert authority in unfamiliar conditions. The result was fragmentation rather than consensus. Religious disputes hardened into confessional divides as competing printed arguments circulated simultaneously. Political pamphlets inflamed factionalism by mobilizing emotion rather than deliberation. Sensational texts, rumors, and polemics traveled alongside serious scholarship with little immediate distinction between them. For critics, this mixture confirmed fears that print had unleashed forces beyond control. Abundance appeared indistinguishable from confusion, and visibility from legitimacy.

This disorder was not random or purely destructive. It followed patterns characteristic of technological transitions. New media tend to reproduce older forms before developing their own conventions. Early print mimicked manuscript genres, rhetorical styles, and institutional assumptions even as it undermined them. Pamphlets echoed sermons. Printed disputations imitated scholastic debate. The persistence of familiar forms created the illusion that continuity had been preserved, even as the underlying conditions of circulation had changed irrevocably.

Over time, repetition and conflict generated adaptation rather than collapse. Readers developed heuristics for trust based on reputation, citation, and genre. Communities of interpretation coalesced around shared standards, whether confessional, scientific, or political. Genres differentiated more clearly, separating ephemeral material from works intended for durability and reference. Scientific communication stabilized around method, documentation, and replicability. Political writing evolved norms of authorship, accountability, and public response. What had once appeared as noise began to resolve into patterns, not because abundance diminished, but because evaluative practices matured to meet it.

The long transition from manuscript scarcity to print abundance thus reveals a recurring historical dynamic. Cultural systems require time to recalibrate when the conditions of production change. Panic arrives early because disorientation is immediate, while adaptation is cumulative and slow. Early modern Europe did not overcome print chaos by returning to scarcity or suppressing circulation, but by inventing new practices of judgment suited to abundance. Coherence was not recovered from the past. It was rebuilt, piece by piece, within the very conditions that initially seemed to threaten it, transforming excess into infrastructure rather than ruin.

What Print Ultimately Enabled

Once the initial turbulence of print culture began to settle, the long-term consequences of textual abundance became increasingly visible. The same mechanisms that had flooded Europe with repetitive pamphlets and polemics gradually enabled sustained intellectual collaboration across distance and time. Print made it possible for arguments to be preserved, revisited, and refined rather than lost to circumstance or locality. Knowledge ceased to be bound to individual institutions or teachers and instead became cumulative. Error could be corrected publicly, claims could be challenged repeatedly, and disagreement could unfold over decades rather than moments. The permanence and replicability of print transformed intellectual conflict from episodic disruption into a durable engine of development.

One of the most consequential outcomes of print was the emergence of modern science. Scientific inquiry depends on reproducibility, shared standards, and open critique, all of which were structurally impossible to sustain at scale within manuscript culture. Print enabled standardized reporting of experiments, consistent terminology, and the dissemination of methods alongside results. Journals, correspondence networks, and printed treatises created a common evidentiary arena in which claims could be evaluated by distant peers rather than asserted by local authority. What earlier critics dismissed as mechanical repetition became the foundation of verification. Repeating experiments, reproducing observations, and citing prior work were no longer signs of intellectual weakness but of rigor. Originality came to mean contribution within an accumulated record rather than novelty detached from precedent.

Print also reshaped literary culture in ways that early critics of abundance could scarcely imagine. The modern novel emerged from the same environment once derided as flooded with romances and formulaic narratives. Extended prose fiction relied on mass readership, stable distribution, and shared conventions made possible by print. These conditions allowed authors to experiment with interiority, social realism, and moral ambiguity across long narrative arcs that demanded sustained attention. Over time, readers developed expectations of coherence, psychological depth, and stylistic consistency. What initially appeared as cultural flattening matured into one of the most complex literary forms in European history, one capable of exploring social structures and individual consciousness with unprecedented subtlety.

The Enlightenment likewise depended on print’s capacity to sustain argument across borders and generations. Philosophical ideas circulated widely, encountered critique, and evolved through response rather than decree. Encyclopedias, pamphlets, treatises, and reviews created a public sphere in which authority was negotiated rather than inherited. Print did not abolish hierarchy, but it made hierarchy answerable. Arguments had to survive exposure, contradiction, and revision. The abundance once feared as noise became the medium through which reason organized itself socially, allowing movements of thought to cohere without centralized control.

Mass literacy followed more slowly but proved no less transformative. As texts became ubiquitous, education systems adapted to train readers capable of navigating volume rather than venerating scarcity. Reading increasingly involved comparison, synthesis, and evaluation across many works rather than mastery of a few. This shift expanded participation in cultural life and redistributed intellectual agency, even as inequalities persisted. Authority came to rest less on access alone and more on interpretive competence.

These developments reveal that the flood of cheap text was not a cultural dead end but a transitional condition that made new forms of meaning possible. The same abundance that unsettled early modern critics enabled scientific method, literary innovation, philosophical exchange, and broad-based education. Print did not preserve culture by limiting repetition. It preserved it by organizing repetition into systems of judgment. What ultimately mattered was not that texts multiplied, but that societies learned how to think with them.

Generative AI and the Repetition Panic Revisited

Contemporary anxieties about generative artificial intelligence echo early modern fears about print with striking precision. Critics argue that AI systems flood the cultural sphere with derivative text, flatten originality, and reward formula over thought. Because generative models are trained on existing material, their outputs are often described as recombinations rather than creations. This has revived an old suspicion: that mechanical reproduction produces cultural noise rather than knowledge. The concern is not simply technological, but moral and epistemic. If meaning is endlessly reproduced, critics ask, does it lose depth, authority, or truth?

Much of this panic rests on an inherited model of originality that predates both industrial and informational abundance. The assumption that creativity must arise ex nihilo mirrors earlier anxieties about pamphlets, romances, and popular print. Generative systems do not invent from nothing, but neither did most human authors operating within print culture, scholarly traditions, or scientific communities. Scholarship has always advanced through citation, response, correction, and accumulation. Literature has long depended on genre, convention, and intertextuality. Journalism synthesizes prior reporting and shared frames. AI makes this dependence visible and unsettling by accelerating it and stripping away the comforting illusion of individual genius. What feels like decline is often exposure: a clearer, less flattering view of how much cultural production has always relied on repetition, pattern, and recombination.

Concerns about quality and authority likewise repeat familiar historical patterns. If anyone can generate text instantly, critics ask, how can standards survive? Yet this question assumes that standards are maintained by restricting production rather than by refining evaluation. Print culture demonstrated that abundance shifts the burden of judgment rather than eliminating it. Generative AI intensifies this shift. It does not abolish expertise. It renders expertise more necessary by separating production from evaluation more cleanly than ever before. The challenge is no longer how to write at scale, but how to assess, contextualize, verify, and curate meaning under conditions of near-infinite output.

There is also a cognitive dimension to the repetition panic that deserves careful attention. Critics worry that AI-generated text will train readers to accept surface coherence without depth, mirroring earlier fears of shallow reading in print culture. This risk is real, but it is neither novel nor inevitable. Every major expansion of textual availability has provoked anxiety about attention, discipline, and intellectual rigor. What history suggests is that reading practices adapt unevenly but persistently. New tools emerge for filtering, annotating, comparing, and cross-checking information. New literacies develop that distinguish provisional synthesis from authoritative knowledge. The presence of repetitive text does not determine intellectual outcomes on its own. Those outcomes depend on the surrounding institutions and norms that govern how texts are used.

Generative AI represents not a rupture but an intensification of long-standing cultural dynamics. Like print, it lowers barriers to production, accelerates circulation, and destabilizes inherited forms of authority. And like print, its early phase is marked by noise, imitation, anxiety, and exaggerated predictions of collapse. The lesson of earlier transitions is not that these fears are irrational, but that they are incomplete. Cultural systems do not survive by preventing repetition. They survive by learning how to organize, evaluate, and discipline it. The central question is not whether AI repeats, but whether societies build the standards, literacies, and institutions necessary to think clearly amid repetition rather than be overwhelmed by it.

Conclusion: Abundance Is Not the Enemy of Meaning

The recurring fear that abundance destroys meaning is one of the most persistent anxieties in cultural history. From ancient scribal schools to Plato’s critique of mimesis, from the flood of early printed pamphlets to contemporary concerns about generative AI, moments of expanded production have repeatedly been interpreted as moments of decline. Yet in every case, the anxiety has mistaken transition for collapse. Meaning has never depended on scarcity alone. It has depended on the practices through which societies interpret, evaluate, and discipline what they produce.

What abundance disrupts is not meaning itself, but inherited forms of authority. When production accelerates, old filters fail first. Elites lose exclusive control. Familiar standards no longer scale. This produces a period of noise, repetition, and uncertainty that feels destabilizing precisely because judgment has not yet adapted to new conditions. But history shows that meaning survives these moments not by retreating to restriction, but by reorganizing itself. New genres, institutions, literacies, and evaluative norms emerge in response to excess. Authority does not vanish. It relocates, often becoming more explicit, contested, and accountable than before.

Print culture ultimately demonstrated that repetition is not the opposite of thought, but one of its enabling conditions. Science advanced through reproducibility, comparison, and cumulative correction, all of which required repeated articulation of methods and results. Literature matured through genre, convention, and intertextual dialogue, allowing writers and readers to recognize patterns and push against them deliberately. Philosophy flourished through sustained debate across texts and generations, in which arguments gained force through reiteration, refinement, and response rather than novelty alone. These developments were not accidental byproducts of abundance. They were achievements made possible by it. What mattered was not that texts multiplied, but that societies learned how to think across multiplication, constructing shared reference points, standards of evidence, and expectations of rigor capable of surviving scale.

Generative AI belongs to this same historical pattern, though its speed and reach intensify the stakes. Its dangers are real, but they are not unprecedented. The challenge it poses is not that it produces too much text, but that it forces a reckoning with how meaning is made when production is no longer scarce. If history offers guidance, it is that abundance does not destroy meaning unless judgment fails to evolve alongside it. Meaning survives when repetition is organized rather than feared, when standards are articulated rather than assumed, and when interpretation remains an active human practice rather than a passive one. Abundance, far from being the enemy of meaning, is the terrain on which meaning has repeatedly been tested, restructured, and ultimately rebuilt.

Bibliography

- Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots.” Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (2021).

- Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken, 1935.

- Blair, Ann. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Chartier, Roger. The Cultural Uses of Print in Early Modern France. Translated by Lydia G. Cochrane. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- —-. The Order of Books: Readers, Authors, and Libraries in Europe between the Fourteenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992.

- —-. Forms and Meanings: Texts, Performances, and Audiences from Codex to Computer. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995.

- Clanchy, M. T. From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307. 3rd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1979.

- Darnton, Robert. The Literary Underground of the Old Regime. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982.

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. “The Emergence of Print Culture in the West.” Journal of Communication 30:1 (1980): 99-106.

- —-. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Erasmus, Desiderius. In Praise of Folly. Translated by Clarence H. Miller. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Febvre, Lucien, and Henri-Jean Martin. The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450–1800. London: Verso, 1997.

- Goetselius, Thomas. “The Vivid Alphabet. Media and Mass Literacy in the Early Modern Military State.” Revue d’histoire De l’éducation 19:2 (2008): 53-82.

- Grafton, Anthony. The Footnote: A Curious History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- —-. Worlds Made by Words: Scholarship and Community in the Modern West. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Grafton, Anthony, and Lisa Jardine. From Humanism to the Humanities: Education and the Liberal Arts in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986.

- Johns, Adrian. The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Leff, Gordon. Paris and Oxford Universities in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. New York: Wiley, 1968.

- Love, Harold. “Early Modern Print Culture: Assessing the Models.” Parergon 20:1 (2003): 45-64.

- Parkes, M. B. Their Hands Before Our Eyes: A Closer Look at Scribes. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008.

- Pettegree, Andrew. The Book in the Renaissance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- —-. The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know about Itself. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

- —-. Reformation and the Culture of Persuasion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Rouse, Richard H., and Mary A. Rouse. Manuscripts and Their Makers: Commercial Book Producers in Medieval Paris, 1200–1500. Turnhout: Brepols, 2000.

- Shapin, Steven. A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

- Southern, R. W. Scholastic Humanism and the Unification of Europe. Vol. 1. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995.

- Striphas, Ted. “Algorithmic Culture.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 18, no. 4–5 (2015): 395–412.

- van Groesen, Michiel and Helmer Helmers. “Managing the News in Early Modern Europe, 1550–1800.” Media History 22:3-4 (2016): 261-266.

- Watt, Ian. The Rise of the Novel. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.27.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.