The history traced here demonstrates that the suppression of dissent in the United States has rarely depended on the abandonment of law.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Security, Dissent, and the Elastic Limits of Law

American governments have long justified extraordinary powers by invoking extraordinary threats. From the early Cold War through the present, federal authorities have repeatedly argued that national security requires surveillance, infiltration, and coercive enforcement against internal dissent. These claims are not new, nor are they confined to moments of declared emergency. What is striking is how often the language of legality has been used to legitimize practices that later generations recognize as corrosive to constitutional order. The history of federal surveillance of journalists and activists reveals a recurring pattern: law is stretched to its elastic limit, then praised for holding.

What follows argues that the weaponization of law enforcement against dissent is not an aberration or a partisan invention but a structural temptation within American governance. Legality has frequently served as camouflage for actions that undermine core constitutional protections, particularly freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of association. Programs such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counterintelligence Program, known as COINTELPRO, did not emerge from lawlessness alone or from isolated bad actors operating beyond institutional control. They grew from a bureaucratic culture that treated dissent as a preemptive threat and enforcement as a form of political management. Within this culture, suspicion became policy and surveillance became routine, reinforced by executive discretion and weak external oversight. Many of the program’s actions were technically lawful under prevailing statutes and executive authorities, yet they were later judged unconstitutional in principle and abusive in effect, revealing the gap that can exist between formal legality and democratic legitimacy.

Journalism occupies a uniquely vulnerable position within this dynamic. Reporters function as witnesses, intermediaries, and amplifiers of dissent, making them persistent targets during periods of state anxiety. When the federal government moves from observing protest to policing narrative, journalists often become objects of intimidation rather than neutral observers. Arrests, surveillance, and prosecutions need not succeed in court to succeed politically. The mere act of enforcement can chill coverage, signal boundaries, and redefine lawful reporting as suspect behavior. This logic has surfaced repeatedly across American history, from Cold War anti-communism to post-9/11 counterterrorism, and remains visible in contemporary enforcement decisions.

Placing recent incidents within this longer historical frame matters precisely because it resists exceptionalism. Arresting a journalist like Don Lemon for covering a protest does not require secret programs or extralegal violence to be effective. It relies instead on inherited habits of intimidation-first governance, where the message matters more than the verdict and process itself becomes punishment. Historical comparison allows us to see how enforcement actions accumulate meaning over time, shaping expectations about what journalists may safely do and what forms of dissent invite retaliation. By examining COINTELPRO and its afterlives, this essay treats modern federal actions not as unprecedented ruptures but as echoes of an established lineage. The danger lies not only in overt repression, but in the quiet normalization of enforcement practices that claim legality while steadily eroding the democratic role of dissent itself.

The Architecture of COINTELPRO: Origins, Justifications, and Scope (1956–1961)

The FBI’s Counterintelligence Program emerged not as an emergency improvisation but as a deliberate administrative response to perceived internal threat. Formalized in 1956, COINTELPRO was initially justified as a necessary instrument for monitoring and neutralizing Communist Party activity within the United States. Federal officials framed the program as defensive, preventative, and temporary, designed to protect democratic institutions from subversion. Yet from its inception, the program’s logic treated political dissent not as a protected constitutional activity but as a latent form of enemy action. This framing allowed surveillance to move seamlessly from observation to intervention.

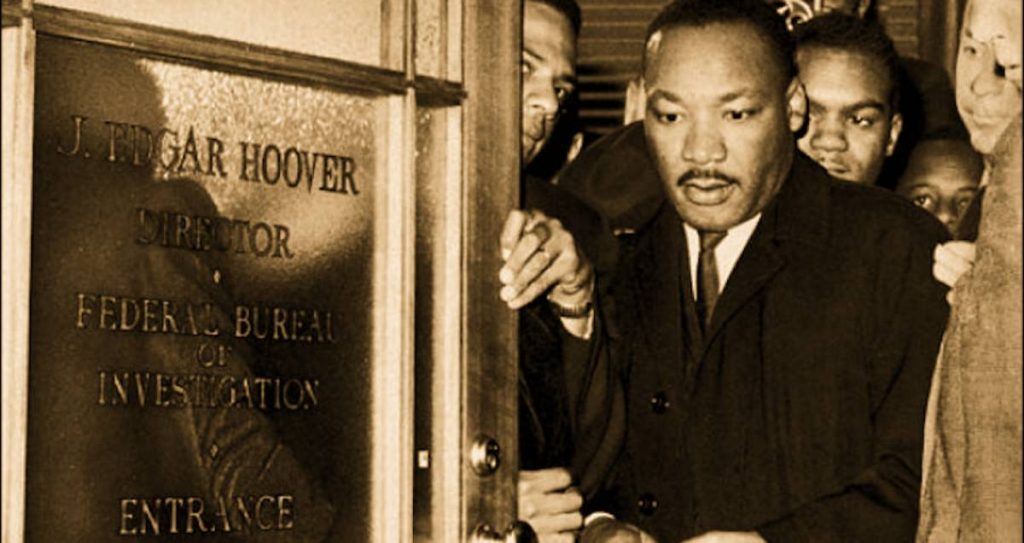

Central to COINTELPRO’s development was the institutional culture of the Federal Bureau of Investigation under Director J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover viewed political radicalism as inherently disloyal and believed that ideological opposition to the state could not be separated from criminal intent. This worldview shaped investigative priorities and normalized extraordinary measures as routine administrative practice rather than exceptional responses. Hoover’s personal authority within the Bureau further entrenched this logic, discouraging internal dissent and insulating policy decisions from ethical challenge. Rather than relying primarily on criminal prosecution, the FBI emphasized disruption, containment, and reputational damage as tools of control. Intelligence gathering was not an end in itself but a means of shaping political outcomes by weakening organizations deemed undesirable and discouraging participation by association.

The early scope of COINTELPRO reflected Cold War anxieties that blurred foreign and domestic threat. While publicly justified as counterespionage, the program focused heavily on American citizens and lawful political organizations. Surveillance extended to labor unions, leftist intellectual circles, student groups, and media figures whose reporting or commentary challenged prevailing national security narratives. The program relied on informants, wiretaps, mail monitoring, and coordination with local law enforcement, often without meaningful judicial oversight. These techniques were embedded within existing legal frameworks, allowing the Bureau to claim compliance while pushing constitutional boundaries.

What distinguished COINTELPRO from conventional intelligence work was its embrace of preventive enforcement. The Bureau did not wait for crimes to occur but acted on anticipated influence and potential persuasion. Internal memoranda emphasized the need to frustrate organizing efforts, sow internal discord, and discourage public credibility. This shift marked a significant departure from traditional law enforcement principles, replacing evidence-based prosecution with anticipatory control. Dissent itself became the object of regulation, not merely its unlawful manifestations.

By the early 1960s, COINTELPRO had established a template that would expand dramatically in subsequent years. Its bureaucratic success lay in its invisibility and its adaptability to changing political priorities. Operating through classified directives and internal authorizations, the program avoided public accountability while embedding itself within routine investigative practice. The absence of external oversight reinforced internal confidence, creating a feedback loop in which effectiveness was measured by disruption achieved rather than rights preserved. These practices ceased to appear extraordinary even to those carrying them out, becoming normalized features of federal enforcement culture. In this way, COINTELPRO became less a discrete program than a governing philosophy, one that redefined the relationship between federal power and political opposition.

Expansion and Radicalization: Civil Rights, Antiwar Movements, and Media Figures (1961–1968)

As the 1960s progressed, COINTELPRO expanded beyond its original anti-communist mandate and adapted to a rapidly changing political landscape. The rise of mass civil rights activism and escalating opposition to the Vietnam War altered the federal government’s perception of internal threat. Dissent was no longer confined to marginal political parties or ideological sects. It was public, morally persuasive, and increasingly effective at mobilizing large segments of the American population. In response, the FBI recalibrated COINTELPRO to target movements whose legitimacy posed a greater challenge to state authority than clandestine subversion ever had.

Civil rights organizations became central targets of this expanded program. The Bureau viewed Black political mobilization through a lens shaped by racialized fear and Cold War paranoia, interpreting demands for equality as potential gateways to radicalization. Martin Luther King Jr. was subjected to extensive surveillance, wiretapping, and psychological harassment, despite the absence of evidence linking him to criminal conspiracy. Internal memoranda framed King not as a lawful political actor but as a destabilizing influence whose moral authority threatened public order. These actions revealed a shift from monitoring ideology to suppressing leadership, influence, and credibility.

Antiwar movements soon followed a similar pattern of treatment. As protest against the Vietnam War grew in scale and intensity, federal authorities increasingly conflated opposition to policy with disloyalty to the nation itself. Student organizations, draft resistance groups, clergy-led peace coalitions, and veterans’ organizations were infiltrated, surveilled, and disrupted. The FBI coordinated closely with university administrators, military officials, and local law enforcement to identify organizers and isolate movement leaders. Informants were used not merely to report activity but to steer conversations, provoke factional disputes, and undermine trust. Rather than addressing unlawful conduct, COINTELPRO initiatives sought to fragment coalitions, exhaust organizers, and erode public sympathy. The emphasis was not on prosecutable offenses but on preventing political success.

Journalists and media figures occupied an especially precarious position within this environment. Reporters covering civil rights demonstrations, urban unrest, and antiwar protests became both observers and perceived facilitators of dissent. The FBI tracked journalists whose reporting challenged official narratives or amplified activist perspectives, particularly those whose work reached national audiences. Surveillance extended to correspondence, sources, and professional associations, creating pressure points that threatened the confidentiality essential to investigative reporting. While formal censorship was rare, the cumulative effect of scrutiny, intimidation, and implied retaliation functioned as an informal mechanism of control. The press was not silenced outright, but it was steadily warned.

The methods employed during this period reflected increasing institutional confidence in disruption as policy. Anonymous letters were sent to employers, spouses, donors, and community leaders. False information was planted to discredit activists and fracture alliances. Legal pressure was selectively applied through tax investigations, draft enforcement, and public order charges. These actions were designed to operate within the appearance of legality while producing outcomes that courts alone could not achieve. The Bureau’s internal assessments measured success by demobilization and reputational damage rather than conviction rates.

By the late 1960s, COINTELPRO had evolved into a comprehensive strategy for managing dissent through administrative means. Its expansion reflected not only political fear but bureaucratic momentum, as each perceived success reinforced confidence in the program’s necessity. New protest movements validated existing tactics and encouraged their wider application across ideological lines. The distinction between national security and political opposition grew increasingly thin, allowing enforcement mechanisms to absorb functions traditionally associated with democratic debate and civil society regulation. This period marked the transformation of COINTELPRO from a targeted counterintelligence effort into a generalized apparatus for suppressing domestic challenge to state policy, one whose effects would linger long after its formal exposure.

“Neutralization” as Policy: Legality without Accountability (1968–1971)

By the late 1960s, the language of COINTELPRO shifted decisively from surveillance and disruption to what the FBI internally described as “neutralization.” This term marked a critical conceptual turn. Neutralization did not require criminal conviction, public justification, or judicial authorization in the conventional sense. It referred instead to rendering individuals or organizations ineffective through cumulative pressure. The policy logic assumed that dissent could be managed administratively, without the constraints imposed by open legal process. In this framework, enforcement was no longer reactive but anticipatory, designed to forestall influence rather than respond to crime.

Legality played a central role in sustaining this approach. Many neutralization tactics operated within the letter of existing law while violating its spirit. Selective enforcement of tax codes, draft laws, immigration rules, and public order statutes allowed federal authorities to apply pressure unevenly while maintaining plausible deniability. Surveillance itself was often justified through broad interpretations of national security authority, even when directed at purely domestic actors with no connection to espionage or foreign influence. The absence of clear statutory limits, combined with deferential judicial attitudes toward national security claims, enabled agencies to claim compliance while evading meaningful constitutional scrutiny. What emerged was a system in which legality functioned as insulation rather than restraint, protecting institutions from accountability rather than citizens from abuse.

Accountability mechanisms proved largely ineffective during this period. Judicial oversight was minimal, in part because many actions never reached the courts. Targets were discouraged, discredited, or exhausted long before formal charges were filed, leaving little opportunity for legal challenge. Congressional oversight was fragmented and deferential, shaped by Cold War assumptions, partisan caution, and institutional secrecy. Even when concerns were raised, access to classified material was tightly controlled, limiting lawmakers’ ability to assess the full scope of activity. Within the FBI, internal review mechanisms reinforced rather than questioned prevailing practices, creating a closed system in which policy goals and enforcement methods validated one another. Success was measured internally by disruption achieved and influence diminished, not by adherence to civil liberties or evidentiary standards.

Journalists and public intellectuals remained particularly exposed to these practices. Neutralization did not require silencing the press outright. It required signaling risk. Surveillance of reporters, cultivation of sources within news organizations, and strategic leaks to friendly outlets served to shape coverage indirectly. The threat of investigation, arrest, or professional damage was often sufficient to encourage caution. In this way, press freedom was constrained not through prohibition but through deterrence, operating entirely within a system that claimed legal legitimacy.

By 1971, COINTELPRO had reached both its widest application and its most fragile position. The very breadth of neutralization efforts increased the likelihood of exposure, as operations multiplied across movements, regions, and institutional boundaries. Secrecy became harder to maintain, and internal confidence increasingly relied on the assumption that legality alone would shield the program from consequence. When exposure finally came, it did not arise from internal reform but from external disruption, revealing how little accountability had existed within formal channels. Yet the core logic of the program remained intact. The concept of legality without accountability, refined during this period, would outlive COINTELPRO itself, establishing a durable model for managing dissent through administrative power that required neither formal repression nor overt illegality to be effective.

Exposure, Public Reckoning, and the Illusion of Closure (1971–1976)

COINTELPRO did not end because it was internally repudiated or constitutionally reconsidered. It ended because it was exposed, abruptly and irreversibly, by actors outside the state. In March 1971, a small group calling itself the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI broke into a Bureau office in Media, Pennsylvania, and stole classified files documenting domestic surveillance and disruption programs. These documents, sent to journalists and members of Congress, revealed the scope and intent of COINTELPRO in unmistakable terms. What had been dismissed for years as speculation or paranoia was suddenly visible in the Bureau’s own words. The exposure shattered the assumption that federal law enforcement operated within self-correcting ethical bounds and forced a public confrontation with practices long protected by secrecy, Cold War deference, and institutional prestige.

Media coverage of the leaked materials played a decisive role in transforming exposure into reckoning. Newspapers published internal memoranda detailing surveillance of civil rights leaders, antiwar activists, and journalists themselves. The credibility of the revelations was difficult to dismiss, as they bore official letterheads and unmistakable institutional language. For the first time, the public was presented with evidence that federal law enforcement had deliberately sought to disrupt lawful political activity. Yet even as outrage spread, official responses remained cautious. The emphasis was placed on procedural excess rather than structural abuse, framing COINTELPRO as a deviation rather than a product of institutional design.

Congressional investigation followed, most notably through the Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, commonly known as the Church Committee. Its hearings between 1975 and 1976 documented widespread violations of civil liberties by the FBI, Central Intelligence Agency, and other intelligence bodies. The Committee concluded that intelligence agencies had repeatedly exceeded their mandates, often targeting Americans for their political beliefs rather than unlawful conduct. Importantly, the investigation exposed not only specific abuses but the normalization of secrecy and discretion as governing principles. Testimony and documentary evidence revealed how internal safeguards had failed systematically, subordinated to institutional loyalty and national security rhetoric. This moment represented a rare instance in which Congress publicly acknowledged that abuse was not accidental but structural. Yet even here, the Committee’s language carefully balanced condemnation with preservation, emphasizing reform rather than dismantlement.

The reforms that emerged from this period created the appearance of closure without resolving underlying tensions. New oversight mechanisms were introduced, including revised FBI guidelines, increased congressional reporting requirements, and the establishment of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. These measures were designed to restore public trust by imposing procedural limits on intelligence activity. However, they left intact the fundamental logic that had enabled COINTELPRO: the belief that national security concerns justified extraordinary discretion, secrecy, and preventive intervention. Oversight focused on authorization rather than purpose, leaving room for reinterpretation under future crises.

The illusion of closure rested on the assumption that exposure equaled correction. COINTELPRO was officially terminated, its name retired, and its excesses publicly disavowed. Yet no senior officials were criminally prosecuted, and institutional memory was managed rather than confronted. Responsibility was diffused across bureaucratic processes rather than assigned to decision-makers. The narrative that COINTELPRO belonged to a uniquely lawless past allowed federal agencies to distance themselves from accountability while preserving operational flexibility. In this sense, the period between 1971 and 1976 marked not an end but a transition. Surveillance and intimidation did not disappear; they were constrained, renamed, and redistributed. The tools remained available, awaiting new crises and new justifications, ensuring that the lessons of exposure would be remembered rhetorically even as they were forgotten operationally.

From COINTELPRO to the War on Terror: Continuity without the Name (1976–2001)

The formal termination of COINTELPRO created a powerful narrative of rupture. Public statements emphasized reform, restraint, and renewed constitutional fidelity, suggesting that the abuses of the past had been identified, corrected, and confined to history. Yet the disappearance of the program’s name did not signal the disappearance of its underlying logic. Instead, the post-1976 period witnessed a careful reconfiguration of domestic intelligence practices, shaped less by moral reckoning than by lessons learned from exposure. Federal agencies adapted by embedding surveillance and disruption more deeply within ordinary investigative frameworks, reducing visibility while preserving capacity. Rather than abandoning controversial practices, they refined them, dispersing authority and normalizing discretion in ways that made future scrutiny more difficult. The result was continuity without explicit acknowledgment, a system designed to operate below the threshold of scandal while retaining the tools necessary to manage dissent.

Revised FBI guidelines issued in the late 1970s and early 1980s illustrate this transformation. These rules nominally restricted investigations based solely on political belief, yet they introduced broad standards such as “national security relevance” and “preliminary inquiry” that granted substantial discretion. The emphasis shifted from ideological targeting to behavioral indicators, a distinction that proved malleable in practice. Political activity could be reframed as potential threat when linked to protest, foreign policy critique, or association with radical groups. This approach allowed surveillance to persist while appearing compliant with reformist intent.

Journalists and activists continued to experience the effects of this recalibration. While overt harassment declined, subtler forms of pressure remained. Monitoring of press organizations, cultivation of confidential sources within media institutions, and informal communication between federal agencies and editors shaped reporting environments. Investigations into leaks and whistleblowers intensified, reinforcing the idea that dissemination of sensitive information constituted a security risk regardless of public interest. The chilling effect did not depend on prosecution. It depended on uncertainty, signaling that scrutiny could follow critical inquiry.

The late Cold War further reinforced this continuity. Concerns over espionage, nuclear proliferation, and political violence provided justification for expanded intelligence coordination across agencies. Domestic surveillance increasingly intersected with foreign intelligence, complicating jurisdictional boundaries and oversight structures. Protest movements opposing U.S. policy in Central America, South Africa, and the Persian Gulf were monitored through this lens, treated as potential vectors of foreign influence rather than expressions of domestic dissent. This reframing allowed authorities to apply national security logic to movements rooted firmly in American civil society. The framework pioneered under COINTELPRO proved highly adaptable, capable of absorbing new geopolitical anxieties without requiring the resurrection of discredited programs by name.

By the 1990s, technological change accelerated these trends. Advances in data collection, electronic communication, and digital record keeping expanded the scope of surveillance while reducing its intrusiveness from the perspective of agents. Information could be gathered passively, stored indefinitely, and cross referenced across multiple databases with minimal human intervention. These developments altered the balance between state power and individual privacy, often without corresponding updates to legal standards or oversight mechanisms. Review processes focused largely on authorization rather than consequence, evaluating whether collection was permitted rather than how it was used. Surveillance became infrastructural rather than exceptional, woven quietly into routine governance and administrative efficiency.

The attacks of September 11, 2001 did not create this system. They activated it. The War on Terror provided the crisis framework that allowed long standing practices to expand rapidly and openly, justified by urgency and fear. Authorities now possessed both the tools and the institutional memory necessary to implement wide ranging surveillance with minimal resistance. In this sense, the post-COINTELPRO era should not be understood as an interlude of restraint followed by sudden excess. It was a period of consolidation, during which the techniques of domestic intelligence were refined, normalized, and prepared for redeployment under a new and far more permissive legal regime.

Post-9/11 Reconstitution: Surveillance as Infrastructure (2001–2016)

The attacks of September 11, 2001 provided the catalytic moment that transformed long-standing surveillance capacities into permanent institutional infrastructure. Emergency measures enacted in the immediate aftermath were presented as temporary responses to an unprecedented threat. Yet the scale and speed of legislative action revealed how thoroughly the groundwork had already been laid. Surveillance authorities expanded not from a vacuum but from a system already conditioned to treat dissent, association, and information flow as matters of security concern. What changed after 9/11 was not merely the scope of surveillance but its status. Practices once justified as exceptional were recast as routine features of governance.

The USA PATRIOT Act dramatically widened federal investigative authority, lowering thresholds for surveillance and information sharing while narrowing avenues for challenge. Provisions allowing roving wiretaps, expanded access to business records, and delayed notification searches blurred distinctions between criminal investigation and intelligence gathering that had previously constrained domestic enforcement. Oversight mechanisms emphasized procedural compliance rather than substantive justification, reinforcing a model in which authorization substituted for accountability. Courts were often limited to reviewing applications in secrecy, without adversarial testing or public scrutiny. The law’s breadth allowed activities directed at journalists, activists, and religious communities to be framed as preventive security measures, even in the absence of individualized suspicion. Surveillance became less an instrument of investigation than a condition of participation in public life, quietly redefining the relationship between citizens and the state.

Journalism faced renewed and intensified pressure under this reconstituted framework. Federal efforts to identify leakers accelerated, and reporters were increasingly treated as potential accessories to unauthorized disclosure rather than as independent actors serving the public interest. Subpoenas for phone records, surveillance of email metadata, and aggressive use of classification regimes constrained investigative reporting on national security matters. These practices did not require convictions to be effective. The chilling effect extended beyond high-profile cases, shaping newsroom behavior and editorial decision-making. Journalists learned to anticipate scrutiny, weigh legal exposure, and limit inquiry in ways that were invisible to audiences but deeply consequential for democratic accountability. Press freedom was not abolished, but it was recalibrated, operating within narrower and less predictable margins of tolerated inquiry.

Technological advances during this period further entrenched surveillance as infrastructure. The exponential growth of digital communication generated vast quantities of data amenable to collection, storage, and analysis. Intelligence agencies developed systems capable of aggregating metadata at scale, often with limited transparency or public understanding. These capabilities altered the nature of surveillance itself. Rather than targeting specific individuals, systems were designed to collect broadly and filter later. Legal frameworks struggled to adapt, frequently deferring to executive interpretation in the name of security efficiency.

By the mid-2010s, revelations about mass surveillance confirmed what critics had long suspected: the post-9/11 state had normalized practices that treated the population itself as a data environment. Congressional hearings and limited reforms followed, but they did little to dismantle the underlying architecture. Oversight focused on marginal adjustments rather than structural change, leaving core authorities intact. Surveillance endured not because it remained secret, but because it had become indispensable to modern governance, embedded in bureaucratic routine and technological dependence. In this reconstituted system, dissent and journalism were not overtly criminalized. They were rendered legible, traceable, and manageable. The legacy of COINTELPRO persisted not in covert operations alone, but in the quiet assumption that security required constant observation.

Intimidation without Prohibition: Journalism under Modern Federal Enforcement (2016–Present)

In the contemporary period, federal pressure on journalism has increasingly taken the form of intimidation without formal prohibition. Unlike earlier eras, the state rarely attempts overt censorship or blanket bans on reporting. Instead, enforcement power is deployed selectively and symbolically, emphasizing disruption, deterrence, and uncertainty. Journalists are not silenced through law, but through exposure to law. Arrests, detentions, equipment seizures, subpoenas, and investigations function as signals, communicating that coverage itself may carry personal and professional risk. The result is a press environment constrained not by explicit rules, but by implied boundaries.

Protest coverage has become a particularly vulnerable site for this form of enforcement. Journalists reporting on demonstrations, immigration enforcement actions, and episodes of civil unrest have faced detention, arrest, or legal scrutiny under public order and obstruction statutes. These actions often occur despite clear identification as members of the press and are later dismissed or quietly dropped. Yet the absence of conviction is beside the point. The process itself imposes cost. Time spent in custody, legal uncertainty, confiscated equipment, delayed reporting, and public association with criminal suspicion all serve to discourage aggressive coverage. Even brief detentions disrupt news cycles and fracture trust between reporters and sources on the ground. Enforcement operates as message rather than outcome, consistent with the historical logic of neutralization refined decades earlier.

Federal authority amplifies this effect when it intersects with national security or immigration enforcement. Journalists covering federal agencies are exposed to expansive discretionary powers exercised in the name of border control, terrorism prevention, or public safety. Administrative tools, rather than criminal prohibitions, dominate this landscape. Credential challenges, restricted access, watchlist ambiguity, and secondary screening create an atmosphere in which journalists cannot easily distinguish lawful scrutiny from punitive targeting. The ambiguity itself becomes functional, encouraging caution and self limitation without requiring formal policy changes.

The cumulative effect on journalistic practice is subtle but profound. Editors and reporters increasingly assess not only the evidentiary strength of a story but its potential to provoke enforcement attention. Legal review becomes preemptive rather than corrective, shaping coverage before facts are fully gathered or narratives fully formed. Sources are harder to cultivate as fear of exposure grows, protests harder to cover as physical risk increases, and federal power harder to interrogate in real time when access is conditional and precarious. Newsrooms quietly recalibrate assignments, weighing institutional risk against public interest. This environment does not resemble the crude repression of earlier periods, yet its impact on democratic accountability may be comparable. Journalism remains legally protected while practically constrained, tolerated but managed through pressure that is diffuse, deniable, and difficult to contest.

This contemporary pattern fits squarely within the historical lineage established by COINTELPRO. The tools have changed, the legal frameworks have evolved, and the rhetoric is more restrained. Yet the underlying dynamic persists. Dissenting narratives are not banned, but they are burdened. Journalists are not forbidden from observing state power, but they are reminded of the cost of doing so too visibly. Intimidation without prohibition preserves the appearance of press freedom while narrowing its effective scope. It is precisely this quiet accommodation between legality and coercion that makes the modern moment historically legible and democratically precarious.

Why COINTELPRO Still Matters

COINTELPRO matters not because it was uniquely extreme, but because it reveals how democratic institutions rationalize the suppression of dissent without abandoning legal form. The program demonstrated that constitutional erosion does not require the suspension of law, the declaration of emergency, or the abandonment of democratic rhetoric. It requires only the strategic use of discretion, secrecy, and administrative authority applied unevenly and defended as necessity. By operating largely within existing legal frameworks, COINTELPRO exposed the fragility of rights that depend on institutional restraint rather than enforceable limits. Its history shows how legality can be decoupled from legitimacy when power is exercised in the name of security, allowing abuses to persist behind procedural compliance and bureaucratic normalcy.

The enduring relevance of COINTELPRO is found in patterns rather than policies. Moments of perceived crisis repeatedly produce similar responses: dissent is reframed as threat, surveillance is justified as prevention, and enforcement is measured by deterrence rather than justice. Each generation insists that its circumstances are exceptional, yet the institutional response remains strikingly consistent. The targets change, the language softens, and the technologies evolve, but the underlying logic persists. COINTELPRO provides the historical template that allows these continuities to be seen clearly rather than dismissed as coincidence or overreach.

Journalism occupies a central place in this continuity because it sits at the intersection of dissent, visibility, and accountability. When journalists are surveilled, detained, or intimidated, the impact extends beyond individual reporters to the public sphere itself. COINTELPRO illustrated how press freedom can be constrained without censorship, through pressure that discourages inquiry rather than forbids it. Surveillance, arrest, and legal uncertainty function as indirect restraints, shaping what can be reported and how boldly it can be pursued. Modern enforcement practices reflect the same dynamic, even when carried out under different statutes and justifications. The absence of formal bans allows institutions to claim fidelity to democratic norms while the practical space for adversarial reporting quietly narrows.

Remembering COINTELPRO is not an exercise in historical condemnation alone. It is a diagnostic tool for the present. It reminds us that abuse of power rarely announces itself as tyranny and seldom arrives fully formed. Instead, it accumulates through precedent, normalization, and forgetting. The danger is not only that institutions may again exceed their authority, but that such excess will be defended as routine, necessary, and lawful. COINTELPRO still matters because it teaches how democracies drift, not by rejecting their principles, but by quietly redefining their limits.

Conclusion: The Old Tools in New Hands

The history traced here demonstrates that the suppression of dissent in the United States has rarely depended on the abandonment of law. Instead, it has relied on the strategic deployment of legal authority in ways that favor enforcement over accountability, discretion over transparency, and deterrence over adjudication. From COINTELPRO’s covert campaigns to contemporary practices of selective policing, surveillance, and administrative pressure, the tools of intimidation have remained remarkably consistent even as their justifications have shifted. What changes are the names, the statutes, and the technologies, not the underlying impulse to manage dissent through pressure rather than persuasion. This continuity reveals a governing habit, not an episodic failure, in which law is treated as an instrument of control rather than a boundary on power.

This continuity challenges comforting narratives of progress. Each cycle of exposure and reform has produced procedural adjustments without fully confronting the structural incentives that reward overreach. Oversight mechanisms tend to regulate form rather than purpose, leaving institutions free to reinterpret constraints in moments of crisis. The result is a pattern in which abuses are condemned retrospectively while the conditions that enabled them persist. Democratic societies risk mistaking regulation for restraint, assuming that legality alone is sufficient to safeguard liberty.

The implications for journalism are particularly severe. A press that operates under constant threat of surveillance, detention, or legal reprisal cannot fully perform its democratic function, even when formal protections remain intact. Intimidation need not silence every voice to be effective. It need only alter behavior enough to limit scrutiny at critical moments. When journalists are treated as potential risks rather than public intermediaries, the balance between state power and public accountability tilts decisively toward secrecy.

The old tools remain effective precisely because they are familiar, adaptable, and rarely framed as extraordinary. They exploit institutional memory, public fear, and legal ambiguity to produce compliance without spectacle and discipline without overt repression. Recognizing this continuity does not require assuming malicious intent or predicting inevitable tyranny. It requires historical clarity and civic vigilance. The lesson of COINTELPRO is not that democracies collapse suddenly, but that they erode through repetition, normalization, and the quiet redefinition of limits. The responsibility of a democratic society is not merely to prohibit overt repression, but to recognize and resist the subtle reappearance of old tools in new hands, before legality once again becomes a substitute for legitimacy.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah. On Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1970.

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

- Burrough, Bryan. Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence. New York: Penguin Press, 2015.

- Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Cole, David and James X. Dempsey, Terrorism and the Constitution: Sacrificing Civil Liberties in the Name of National Security. New York: The New Press, 2006.

- Department of Justice, Office of the Inspector General. A Review of the FBI’s Use of National Security Letters. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2007.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. COINTELPRO Black Nationalist–Hate Groups Program. Declassified records. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, COINTELPRO Memoranda, 1956–1961 (declassified documents).

- Greenwald, Glenn. No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2014.

- Halperin, Morton H., Jerry J. Berman, Robert L. Borosage, and Christine M. Marwick. The Lawless State: The Crimes of the U.S. Intelligence Agencies. New York: Penguin Books, 1976.

- Johnson, Loch K. A Season of Inquiry: The Senate Intelligence Investigation. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1985.

- Mellen, Joan. Blood in the Water: How the U.S. and Israel Conspired to Ambush the USS Liberty. New York: Skyhorse, 1988.

- Mullgardt, Brian. “’Further Harassment and Neutralization’: The FBI's Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) in Illinois.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 113:3-4 (2020): 94-120.

- Price, David H. The American Surveillance State: How the U.S. Spies on Dissent. London: Pluto Press, 2022.

- Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board. Report on the Surveillance Program Operated Pursuant to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. Washington, DC: PCLOB, 2014.

- Pyle, Christopher H. Military Surveillance of Civilian Politics. 1967-1970. New York: Garland Publishing, 1986.

- Schrecker, Ellen. Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

- Snyder, Timothy. On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2017.

- Stone, Geoffrey R. Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism. New York: W. W. Norton, 2004.

- Theoharis, Athan G. The FBI and American Democracy: A Brief Critical History. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

- United States Congress. Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act of 2001. Pub. L. No. 107–56, 115 Stat. 272.

- United States Senate, Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1976).

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.02.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.