Slavery was sustained not only by violence on plantations or decisions in Parliament, but by the routine flow of money from consumers.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Consumption as Complicity

In late eighteenth-century Britain, political power was formally concentrated in Parliament and property, excluding large segments of the population from direct participation in governance. Women, the poor, and most laborers possessed no vote and no institutional pathway through which to influence imperial policy. Political legitimacy was tightly bound to landownership, patronage, and elite networks, leaving moral outrage without a clear constitutional outlet. Yet these same groups were deeply embedded in Britain’s expanding consumer economy, participating daily in markets that linked households to imperial production. Abolitionists recognized that while formal political power was restricted, economic participation was nearly universal. Everyday consumption, rather than legislative authority, became the terrain on which moral responsibility could be asserted and collective action organized. What could not be spoken in Parliament might still be expressed at the counter, the table, and the shop.

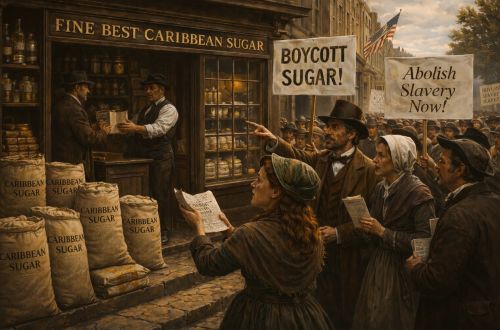

Sugar occupied a unique position within this moral economy. Once a luxury, it had become a staple of British domestic life, consumed daily in tea, baking, and preserved foods. Its ubiquity concealed the violence of its production. Enslaved labor on Caribbean plantations was geographically distant, legally insulated, and economically normalized within imperial commerce. Abolitionists confronted a paradox. Many Britons did not own slaves and exercised no direct control over colonial policy, yet their routine purchases sustained the plantation system. Sugar exposed the gap between moral self-perception and material consequence.

The abolitionist sugar boycott reframed that gap as complicity. Activists argued that innocence could not be claimed through distance alone. If consumption enabled slavery, then abstention became a moral obligation. This reframing was radical in its implications. It shifted responsibility from institutions to individuals, from ownership to participation. The question was no longer whether one possessed slaves, but whether one financed them. In doing so, abolitionists transformed private household decisions into acts of political significance, rendering the domestic sphere a site of ethical judgment and public consequence.

What follows argues that the success of abolitionist boycotts rested on this reconceptualization of responsibility and its translation into sustained collective action. By moralizing consumer withdrawal, activists created a form of political pressure accessible to those excluded from formal power, particularly women who organized, promoted, and enforced abstention within households and communities. The boycott worked not because it was symbolic, but because it was collective, durable, and strategically targeted at powerful economic actors whose profits depended on mass consumption. Merchants, refiners, and colonial interests could not easily dismiss or repress abstention without addressing its causes. Consumption was exposed as a choice with moral weight, and abstention as a form of action capable of shaping political debate. In revealing participation itself as a mechanism of oppression, abolitionists demonstrated how economic distance could be converted into moral pressure, reshaping the relationship between private behavior and public injustice.

Slavery, Sugar, and the British Economy

By the late eighteenth century, sugar was no longer a peripheral commodity but a central pillar of Britain’s commercial economy. Caribbean plantations supplied vast quantities of raw sugar that flowed into British ports, refineries, and domestic markets, linking colonial production to metropolitan consumption through dense financial and logistical networks. Sugar revenues underwrote shipping, insurance, and credit markets, while investment in plantations and associated trades tied merchants, financiers, and manufacturers to enslaved labor. Customs duties on sugar imports made the commodity fiscally indispensable to the state, embedding slavery within public finance as well as private profit. The scale of this integration meant that slavery was not an external moral problem confined to distant colonies but an internal economic fact, woven into everyday transactions across Britain.

The transformation of sugar from luxury to staple was crucial to this entanglement. Rising wages, falling prices, and expanding colonial supply made sugar accessible to households far beyond the elite. It sweetened tea, preserved fruits, and entered the diets of working families as a routine consumable. This mass consumption altered the moral geography of slavery. Enslaved labor was no longer connected solely to distant plantations or imperial elites but to ordinary domestic life. The normalization of sugar consumption blurred responsibility, allowing Britons to benefit materially from slavery without confronting its human cost directly.

Behind this apparent ordinariness stood a complex commercial system that distributed profits widely. Planters depended on metropolitan merchants for credit and marketing, refiners for processing, insurers for risk management, and shipowners for transport. Parliamentary interests were intertwined with these sectors through investment, patronage, and fiscal policy. Slavery operated less as a single institution than as a networked economy, sustained by participation at multiple levels. Any challenge to sugar consumption threatened not only colonial producers but the commercial infrastructure that bound empire and metropole together.

This integration helps explain why abolitionist arguments that focused solely on planter cruelty or colonial reform proved insufficient. The problem was not confined to the Caribbean. British prosperity itself was implicated. Sugar profits circulated through banks, ports, and shops, financing urban development and consumer abundance. Abolitionists who grasped this reality recognized that moral appeals aimed at Parliament alone could not disrupt such a system. The economic foundations of slavery lay as much in British demand as in colonial supply.

The state’s reliance on sugar further entrenched resistance to reform and sharpened the political stakes of abolitionist pressure. Customs revenues from sugar imports formed a significant component of government income, making abolition appear fiscally risky at moments of war, debt, and imperial competition. Political leaders warned that disrupting sugar markets would damage trade balances, provoke unemployment, and weaken national prosperity. These arguments framed slavery as an unfortunate but necessary component of economic stability. While such claims often exaggerated the dangers of reform, they reflected genuine dependence on sugar revenues and reinforced the perception that abolition threatened the public interest as well as private profit.

Understanding slavery’s place within the British economy clarifies why the sugar boycott represented such a strategic intervention. By targeting consumption rather than production, abolitionists confronted the domestic foundations of slavery directly and forced recognition of Britain’s own involvement. Abstention challenged the assumption that economic benefit and moral distance could coexist. It exposed the degree to which slavery depended on everyday British participation and made the costs of complicity visible within the metropole itself. Sugar was not merely a symbol of slavery. It was one of its primary engines, and withdrawing demand struck at the heart of the system that sustained it.

Political Exclusion and the Search for Leverage

The emergence of abolitionist boycotts cannot be understood apart from the severe constraints on political participation in late eighteenth-century Britain. Formal power resided in Parliament, which was dominated by property owners, patrons, and imperial interests closely tied to colonial commerce. Voting rights were narrowly restricted, representation was uneven, and access to office was largely closed to women and the working poor. For most Britons, moral opposition to slavery had no direct institutional outlet. Political exclusion was not incidental to abolitionist strategy. It was the condition that made alternative forms of influence necessary.

Women, though long beneficiaries of slavery, were especially central to this search for leverage, not simply as supporters of abolition but as its primary organizers and enforcers. Barred from voting, officeholding, and most forms of formal political association, women nevertheless exercised substantial authority within households and local communities. They controlled purchasing decisions, managed domestic labor, organized social networks, and shaped moral norms within families. Abolitionist organizers explicitly recognized this influence and appealed to it, framing consumer choice as a site of political action rather than private preference. Pamphlets, sermons, and visual materials targeted women as moral arbiters of the household, urging them to refuse slave-produced sugar and encourage others to do the same. In this way, domestic authority was transformed into collective leverage, allowing women to participate decisively in a movement that formally excluded them.

Economic participation offered what formal politics denied: scale, visibility, and persistence. While petitions, meetings, and pamphlets circulated intermittently and reached limited audiences, consumption linked abolitionist commitment to daily behavior with measurable economic consequences. Every purchase of sugar reinforced the plantation system, while every refusal represented a small but tangible disruption. When multiplied across thousands and eventually millions of households, abstention became visible to merchants, refiners, and wholesalers who tracked sales and profits closely. This reframing allowed individuals excluded from political institutions to exert pressure directly on economic actors whose interests were represented in Parliament. Consumer withdrawal bypassed political gatekeeping by acting on incentives that elites could not ignore, translating moral conviction into material consequence.

The search for leverage produced a strategic shift in how political responsibility was understood. Abolitionists did not abandon Parliament, but they no longer treated it as the sole arena of change. Instead, they redefined political participation to include economic behavior, moral discipline, and collective restraint exercised outside formal institutions. Abstention became a means of asserting agency where legal power was absent. By exposing the dependence of slavery on mass participation rather than elite decision alone, abolitionists demonstrated that exclusion from politics did not preclude influence over political outcomes.

Organizing the Sugar Boycott

The abolitionist sugar boycott did not emerge spontaneously from individual moral awakening. It was the product of deliberate organization, communication, and coordination across social networks that connected households to national campaigns. Abolitionist societies, religious groups, and informal community circles worked together to disseminate the idea that abstention was both necessary and effective. The boycott depended on shared understanding and mutual reinforcement. Without organization, individual refusals would have remained isolated gestures. With it, abstention became a collective practice capable of producing economic and political effects.

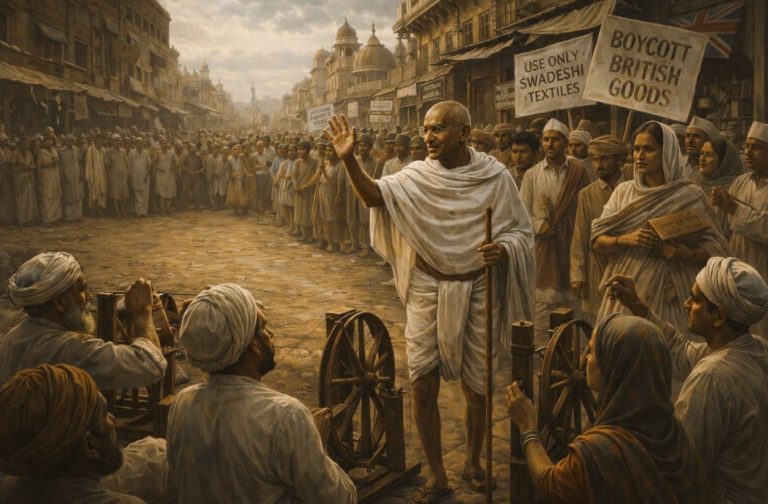

Printed materials played a crucial role in this process by translating distant systems of exploitation into accessible moral narratives. Pamphlets, broadsides, sermons, and circular letters explained in clear terms how sugar consumption sustained enslaved labor, often providing vivid descriptions of plantation conditions to overcome geographic distance. Visual culture amplified these messages further. Medallions, prints, and illustrations bearing images of enslaved Africans and slogans such as “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” condensed complex economic relationships into immediately recognizable symbols. These objects circulated widely, appearing in homes, churches, and public gatherings, reinforcing the boycott’s message through repetition. By embedding moral argument in material culture, abolitionists ensured that the connection between sugar and slavery remained visible in everyday life.

Household networks were equally important. Women organized conversations in domestic spaces, churches, and charitable associations, reinforcing norms of abstention and monitoring compliance. Refusing sugar was framed not as a private sacrifice but as a public commitment visible to family, guests, and neighbors. Social pressure worked alongside moral conviction. Offering sweetened tea became an ethical test, and abstention signaled membership in a community defined by conscience. This embedding of the boycott within everyday social interaction helped maintain discipline over time, preventing enthusiasm from dissipating after initial mobilization.

The scale and duration of participation distinguished the sugar boycott from symbolic protest and gave it material significance. Contemporary observers reported noticeable declines in sugar consumption during peak periods of abstention, particularly in the late 1780s and early 1790s, even if precise figures remain debated. Enterprises monitored sales closely and expressed concern about falling demand, disrupted inventories, and unpredictable markets. Newspaper commentary and commercial correspondence reveal growing anxiety that consumer behavior was becoming politicized in ways difficult to control. The persistence of the boycott mattered as much as its breadth. Sustained abstention over months and years signaled that moral commitment would not fade quickly, forcing economic actors to acknowledge that the movement represented a structural challenge rather than a passing moral fashion.

Crucially, organizers emphasized that the boycott targeted systems rather than individuals. Abstention was directed at slave-produced sugar, not at fellow consumers who struggled to comply. This framing avoided moral absolutism and allowed participation to expand gradually. By presenting refusal as a collective effort rather than a test of purity, abolitionists maintained broad support and minimized fragmentation. Organization transformed abstention into a durable political instrument, demonstrating that consumer withdrawal could be disciplined, scalable, and strategically focused rather than merely expressive.

Targeting Complicity, Not Producers

A distinctive feature of the abolitionist sugar boycott was its deliberate focus on complicity rather than on enslaved producers themselves. Abolitionists understood that enslaved laborers were victims of the system, not agents within it, and therefore rejected approaches that would punish those already subjected to violence and coercion. The goal was not to disrupt plantation labor directly or impose additional suffering on enslaved people, but to sever the economic chains that bound British consumers to colonial exploitation. By directing moral responsibility toward consumers, merchants, refiners, and investors, abolitionists relocated the site of accountability from distant plantations to the metropole. Slavery was no longer framed solely as a colonial problem but as a domestic one, sustained by everyday choices made far from the fields and mills of the Caribbean.

This logic represented a significant ethical innovation in political activism. Responsibility was no longer tied exclusively to ownership, legal authority, or direct control over enslaved people, but to participation within an interconnected economic system. Britons who had never seen a plantation, held a whip, or purchased a human being were nevertheless implicated through their consumption and investment. Abolitionist rhetoric emphasized that distance did not absolve guilt when profits, comforts, and pleasures flowed directly from coerced labor. Buying sugar was framed as a tacit endorsement of slavery, while refusing it became a moral declaration. Complicity was exposed not as an exceptional condition affecting only elites, but as an ordinary feature of imperial life that demanded conscious reckoning.

By targeting complicity, abolitionists avoided strategies that risked reproducing harm. Calls to punish planters or disrupt production directly could invite brutal retaliation against enslaved people or provoke colonial resistance that hardened opposition. Consumer withdrawal, by contrast, imposed costs on those who benefited from slavery without increasing violence against those trapped within it. The boycott aligned moral intent with ethical means. It sought to weaken slavery’s economic foundations while minimizing unintended harm, demonstrating a strategic sensitivity often absent from more confrontational approaches.

This focus on complicity also broadened participation. One did not need wealth, influence, or proximity to plantations to act. Moral responsibility was accessible to anyone who purchased sugar, making abstention a democratic form of pressure. The boycott encouraged self-examination rather than denunciation, inviting individuals to recognize their own role within a larger system. In doing so, abolitionists transformed consumption into a site of ethical reckoning, where opting out became a way to confront injustice without reproducing it.

Economic Disruption and Elite Reaction

The sugar boycott mattered because it translated moral refusal into economic disturbance that elites could not easily dismiss. Even partial abstention by large numbers of consumers altered demand patterns in a market accustomed to steady growth. Businesses watched revenues closely, and fluctuations generated anxiety disproportionate to their immediate scale. The boycott revealed how dependent the sugar economy was on predictable consumption rather than coercive enforcement. Unlike plantation labor, demand could not be compelled. When buyers hesitated, the entire commercial chain felt the strain.

Elite reaction was swift and defensive, reflecting both material concern and ideological unease. Merchants and colonial advocates questioned the scale of the boycott, dismissed its moral premises, and warned publicly of economic collapse should abstention spread further. Pamphlets, editorials, and parliamentary speeches emphasized employment losses, reduced customs revenue, and threats to Britain’s commercial standing. These arguments framed the boycott as irresponsible and destabilizing, casting consumers as naïve or manipulated. While such claims often exaggerated the material damage, their urgency was revealing. They acknowledged that consumer behavior had become politicized and that economic pressure was being applied from below rather than negotiated among elites. The very effort to minimize the boycott’s significance demonstrated an awareness that markets were proving more responsive to moral pressure than anticipated.

Parliamentary debate reflected this discomfort. While abolitionist arguments had circulated for decades, consumer withdrawal introduced a new variable into legislative calculations. Members of Parliament who remained ambivalent about abolition were forced to consider the reputational and fiscal consequences of ignoring popular moral pressure. Even those unsympathetic to abolition recognized that prolonged disruption risked unsettling commercial confidence and public trust. The boycott did not dictate parliamentary outcomes directly, but it altered the political environment in which decisions were made, increasing the perceived costs of inaction and delay.

Economic elites also feared precedent, and this anxiety extended beyond sugar itself. If consumers could organize effectively against slave-produced sugar, similar tactics might be applied to other commodities or exploitative practices embedded in imperial commerce. The boycott demonstrated that markets could become sites of moral contestation rather than neutral arenas of exchange governed solely by price and supply. This possibility threatened established hierarchies of influence, in which economic power flowed upward and political decisions were insulated from popular intervention. Elite resistance to the boycott reflected concern about its broader implications as a model of economic activism, not merely its immediate impact on profits.

The reaction of merchants and political leaders confirmed the boycott’s effectiveness more clearly than consumption figures alone. Defensive rhetoric, intensified lobbying, and attempts to discredit abstention signaled that consumer withdrawal had struck a sensitive nerve within Britain’s political economy. Economic disruption did not need to be catastrophic to be consequential. It only needed to be credible, sustained, and visible enough to force recognition that moral refusal could reshape incentives. In provoking elite response and forcing public engagement, the sugar boycott demonstrated that organized economic pressure could penetrate spaces of power otherwise closed to reformers.

Moral Economy and the Language of Refusal

The sugar boycott functioned not only as an economic tactic but as a transformation of moral language surrounding consumption. Abolitionists drew upon an emerging moral economy in which market behavior was subject to ethical judgment rather than treated as value-neutral exchange. Refusal was framed as a positive moral act, not a passive absence of consumption. To abstain from sugar was to declare allegiance to a shared ethical standard that linked private behavior to public justice. This language allowed ordinary consumers to understand their choices as morally legible actions within a collective struggle.

Central to this moral economy was the reframing of abstention as duty rather than sacrifice, a move that proved essential to sustaining participation. Abolitionist rhetoric avoided portraying the boycott as an act of heroic deprivation or personal suffering. Instead, it emphasized proportionality and perspective, insisting that true hardship belonged to enslaved laborers, not to those who forwent sweetness in tea. This rhetorical move inverted conventional assumptions about comfort and entitlement, exposing everyday pleasures as morally contingent rather than neutral. Sugar was recast as a tainted good whose consumption carried ethical cost, while refusal became a form of moral hygiene. Abstention signaled discipline, conscience, and restraint, transforming moderation into virtue and habitual indulgence into ethical failure without resorting to overt moral condemnation.

The communal nature of this moral language was equally important. Abolitionists encouraged participants to see themselves as part of a broader ethical community bound by shared refusal. Public pledges, collective statements, and visible practices reinforced this identity. Refusal gained meaning through recognition. When neighbors, congregations, and social circles adopted abstention together, moral commitment was normalized rather than exceptional. This collective framing prevented abstention from becoming isolating or performative. Instead, it functioned as a social norm sustained through mutual accountability and shared values.

The language of refusal also reshaped how power was addressed and resisted. Rather than appealing directly to authority through petitions or supplication, abolitionists spoke past formal institutions and addressed consumers as moral agents capable of withdrawing consent. This rhetorical shift reduced dependence on elite approval and emphasized horizontal solidarity over vertical petitioning. By treating participation itself as the problem, abolitionists made refusal a form of speech that did not require permission, legitimacy, or representation. Abstention operated simultaneously as ethical expression and political pressure, allowing individuals excluded from power to act without waiting for recognition. In this moral economy, restraint became communicative, and silence in the marketplace became a language elites were forced to hear.

Rethinking Power in Abolitionist Politics

The sugar boycott compels a reassessment of how power operated within abolitionist politics and how political change was actually generated in late eighteenth-century Britain. Traditional narratives often privilege parliamentary maneuvering, elite advocacy, and legislative milestones, presenting abolition as the result of moral persuasion within formal institutions. While these elements mattered, they obscure the extent to which abolitionist momentum was produced outside Parliament and often in advance of legislative action. Consumer withdrawal functioned as a parallel political arena, one in which power was exercised without office, vote, or formal authority. The boycott reveals that influence did not flow exclusively through representation or debate, but could be exerted through coordinated nonparticipation that altered the material context in which political decisions were made.

This reframing challenges assumptions about agency in late eighteenth-century Britain by highlighting the political effectiveness of those formally excluded from power. The individuals most active in the boycott were frequently those least empowered by law. Women, religious dissenters, and working households lacked access to decision-making bodies, yet they shaped the political environment by altering patterns of economic behavior. Power emerged not from command or coercion, but from aggregation. Individual refusals accumulated into collective force, creating pressure without leadership, hierarchy, or centralized control. Abolitionist politics operated through a decentralized model of influence, demonstrating that sustained coordination could substitute for formal authority.

Economic withdrawal also complicates the distinction between moral and political action. The boycott was rooted in ethical conviction, but its effectiveness depended on material consequences. It blurred the boundary between conscience and strategy, showing that moral behavior could be politically consequential when organized collectively. This fusion unsettled elites who preferred to treat markets as apolitical spaces. By politicizing consumption, abolitionists exposed the vulnerability of economic systems to moral scrutiny, redefining power as the capacity to withhold cooperation rather than impose compliance.

Rethinking power in this context also requires attention to durability and scale. Unlike episodic protests, riots, or rebellions, the boycott embedded political pressure within routine behavior that could be sustained across time and geography. Its influence persisted not through spectacle but through repetition, turning daily acts of refusal into cumulative force. This endurance made the boycott difficult to suppress, discredit, or isolate as extremist. There was no single leader to arrest, no gathering to disperse, no moment of confrontation to crush. Power exercised through habit proved more resilient than power asserted through confrontation, suggesting that longevity and normalization themselves functioned as political leverage.

The abolitionist sugar boycott reveals a model of political power grounded in participation and refusal rather than command. It shows that systems dependent on widespread cooperation are vulnerable to organized withdrawal, even when coercive authority remains intact. Abolitionist politics did not merely appeal to conscience; they restructured the terrain on which conscience could act. By transforming consumption into leverage, the movement demonstrated that power could be exercised horizontally, quietly, and persistently, reshaping political outcomes without seizing control of institutions.

Conclusion: When Abstention Becomes Action

The abolitionist sugar boycott demonstrates that political action need not take the form of direct confrontation, institutional participation, or revolutionary rupture to be effective. By refusing to consume slave-produced sugar, British abolitionists transformed abstention into a form of collective agency capable of reshaping economic incentives and political calculations. What appeared outwardly as private moral choice operated in practice as coordinated pressure applied across markets, households, churches, and social networks. Abstention became action not because it was dramatic or disruptive in isolation, but because it was sustained over time, shared across communities, and strategically targeted at systems that depended on mass participation. The boycott revealed that quiet, repetitive acts, when synchronized at scale, could exert force comparable to more visible forms of protest.

This strategy succeeded by exposing participation itself as a source of power and vulnerability. Slavery was sustained not only by violence on plantations or decisions in Parliament, but by the routine flow of money from consumers to merchants, refiners, insurers, and colonial investors. The boycott made that flow visible and contestable, collapsing the moral distance between household consumption and imperial exploitation. By withdrawing consent expressed through everyday purchases, abolitionists demonstrated that economic systems are vulnerable at their points of dependence. When enough participants refused to cooperate, the system could not function as designed. Abstention became a means of intervention that operated without seizing authority, issuing commands, or appealing to elite goodwill, relying instead on the structural necessity of cooperation.

The moral significance of the boycott lay in its insistence that distance does not negate responsibility. Abolitionists rejected the comfort of moral innocence grounded in separation from violence. Instead, they argued that benefiting from exploitation implicated consumers regardless of intent. This reframing reshaped ethical discourse by linking everyday behavior to structural injustice. Abstention offered a way to act upon that recognition without reproducing harm. It allowed individuals excluded from formal power to participate in political change through disciplined refusal rather than delegated authority.

When abstention becomes action, power reveals its reliance on cooperation rather than coercion. The sugar boycott illustrates how collective withdrawal can alter political outcomes by transforming private behavior into public pressure. This lesson extends beyond abolitionist politics. It suggests a broader principle of political economy. Systems that depend on voluntary participation are constrained by it. By refusing to buy, abolitionists forced recognition of a simple truth. Authority cannot compel consent indefinitely. Where money stops moving, power is forced to listen.

Bibliography

- Brown, Christopher Leslie. Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Drescher, Seymour. Econocide: British Slavery in the Era of Abolition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

- Inikori, Joseph E. Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England: A Study in International Trade and Economic Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Midgley, Clare. Women Against Slavery: The British Campaigns, 1780–1870. London: Routledge, 1992.

- —-. “Slave Sugar Boycotts, Female Activism, and the Domestic Base of British Anti-Slavery Culture.” A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies 17:3 (1996): 137-162.

- Oldfield, J. R. Popular Politics and British Anti-Slavery: The Mobilisation of Public Opinion against the Slave Trade, 1787–1807. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995.

- Richardson, David. “The British Empire and the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1660–1807.” In The Oxford History of the British Empire, vol. 2, edited by P. J. Marshall, 440–464. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Richardson, David. “The Slave Trade, Sugar, and British Economic Growth, 1748-1776.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History XVII:4 (1987): 739-769.

- Sussman, Charlotte. “Women and the Politics of Sugar, 1792.” Representations 48 (1994): 48-69.

- Terwiel, Anna. “The Revolutionary Politics of Abolition.” Polity 55:4 (2023): 662-672.

- Thompson, E. P. “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century.” Past and Present 50 (1971): 76–136.

- Walvin, James. Sugar: The World Corrupted, from Slavery to Obesity. London: Robinson, 2017.

- Williams, Eric. Capitalism and Slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1944.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.03.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.