The Bona Dea scandal endures not because of its lurid details or famous participants, but because it exposes a structural failure that remains politically relevant.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Scandal Stops Working

Political scandal is often treated as a self-correcting mechanism. The exposure of wrongdoing is assumed to generate outrage, compel accountability, and restore institutional norms. This assumption underlies both ancient and modern confidence in public judgment, as if evidence naturally produces consequences once placed before a civic audience. Yet history offers repeated examples in which scandal fails to perform this function. In such moments, revelation does not clarify truth or discipline power. Instead, it accelerates division, hardens loyalties, and exposes the limits of shared reality itself.

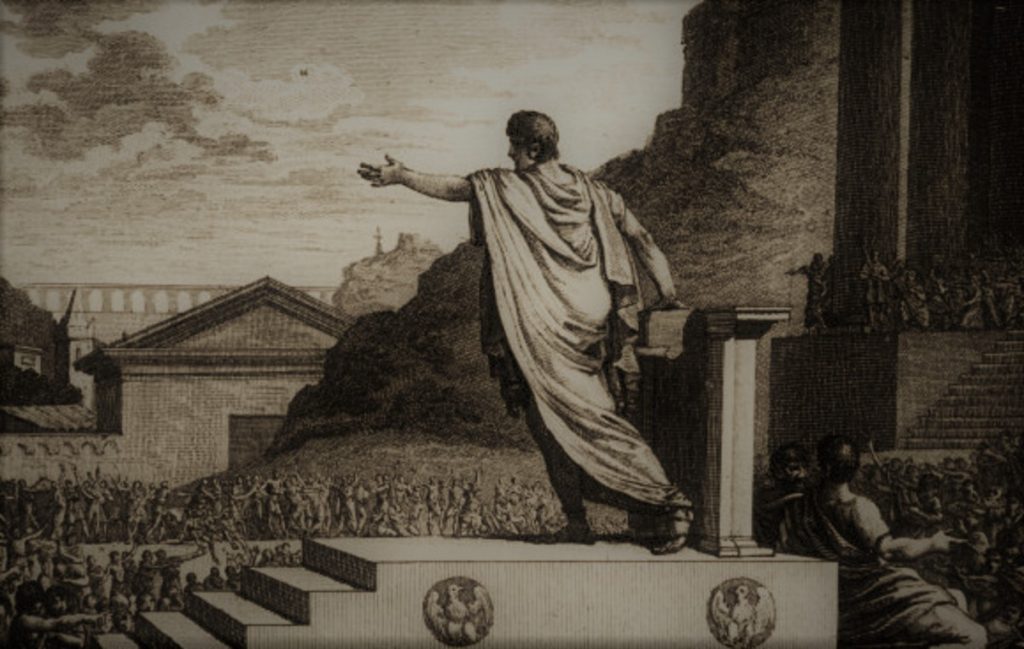

The late Roman Republic provides one of the clearest early cases of this failure. By the first century BCE, Roman political life had become intensely personalized, polarized, and distrustful of neutral authority. Institutions that once mediated conflict now functioned as battlegrounds rather than arbiters. Courts, assemblies, and religious rites were no longer trusted as spaces of collective judgment but were interpreted through partisan expectation. In this environment, scandal did not destabilize authority so much as reveal which communities of belief already existed beneath the surface of public life.

The Bona Dea scandal of 62 BCE sits squarely within this transformation. Clodius was accused of infiltrating a women-only religious rite, a violation that combined sacrilege, sexual impropriety, and elite moral hypocrisy. The evidence against him was substantial, the testimony credible, and the stakes unmistakably public. Yet the outcome of the trial was not determined by proof. Clodius was acquitted through a mixture of intimidation, bribery, and partisan solidarity. More striking than the acquittal itself was the reaction it produced. His supporters dismissed the charges as fabrication and elite conspiracy. His opponents treated innocence as absurd. Both sides claimed certainty, and neither recognized the other’s standards as legitimate.

What follows argues that the Bona Dea affair reveals a deeper structural failure in Roman political culture: the emergence of incompatible truth communities in which scandal ceased to function as accountability and instead became a weapon of group identity. In this context, evidence could accumulate without resolution, verdicts could be rendered without legitimacy, and public knowledge could fracture without repair. The problem was not ignorance, nor the absence of facts, but the collapse of shared criteria for believing them. Once scandal becomes partisan property rather than a civic judgment, its corrective power disappears. The late Republic did not fall because Romans lied to one another. It fell because they no longer agreed on how truth could be known at all.

The Bona Dea and the Meaning of Sacrilege

The Bona Dea rites occupied a distinctive place in Roman religious life, combining secrecy, gendered exclusion, and elite moral symbolism. Celebrated annually in December, the rites were restricted to women and conducted under conditions that emphasized ritual purity and domestic sanctity. Men were categorically excluded, even in name, and the presence of wine was euphemistically disguised to preserve the goddess’s moral associations. These features were not incidental. They marked the ceremony as a protected space in which Rome’s ideals of female virtue, aristocratic decorum, and divine favor were ritually affirmed.

Religious practice in Rome was inseparable from political legitimacy in ways that modern categories often obscure. Roman religion did not function as private belief or interior conviction but as a public system of obligation, performance, and reciprocity. The gods were understood to grant protection, prosperity, and victory in exchange for correct ritual observance, not moral intention alone. This meant that error, negligence, or violation in ritual practice carried consequences for the entire community, regardless of who committed it. Sacrilege posed a civic danger rather than a purely ethical one. When rites were violated, anxiety focused less on individual guilt than on the risk that Rome’s relationship with the divine world had been compromised. A polluted ritual threatened the pax deorum, the fragile harmony believed to sustain Rome’s power, stability, and historical destiny.

The Bona Dea rites were particularly sensitive in this regard because of their intimate association with elite households and political authority. In 62 BCE, the ceremony was hosted in the home of Julius Caesar, who at the time served as pontifex maximus, Rome’s chief priest. This setting intensified the symbolic stakes of the ritual. The residence of the pontifex maximus was not merely a private dwelling but a semi-public space invested with religious authority. It was expected to embody ritual correctness, moral discipline, and trustworthiness at the highest level. Any violation within that space could not be dismissed as accidental or trivial. It implicated the credibility of Rome’s religious leadership and raised uncomfortable questions about whether the guardians of sacred order were capable of enforcing the boundaries they publicly defended.

Clodius’s alleged intrusion struck at each of these symbolic layers simultaneously. By entering the ceremony disguised as a woman, he violated gender boundaries, religious law, and elite moral expectations in a single act. The offense could be framed as sexual impropriety, sacrilege, or political provocation, and contemporaries did all three. What made the charge explosive was not prurience but symbolism. The act suggested that sacred boundaries could be mocked, manipulated, or ignored by those with sufficient audacity or protection. That implication threatened the moral authority of the ruling class itself.

Understanding the intensity of the scandal requires recognizing that sacrilege in Rome was not metaphorical. It was institutional. The Bona Dea affair was alarming because it implied that the rituals anchoring Rome’s moral and cosmic order could be breached without consequence. If the gods could be deceived or insulted within the household of the chief priest, then the distinction between sacred obligation and political convenience had already collapsed. The trial that followed was not merely about whether Clodius had committed an offense. It was about whether Roman religion still possessed the authority to bind its most powerful citizens.

Publius Clodius Pulcher: Persona, Power, and Polarization

Publius Clodius Pulcher was not a marginal provocateur whose scandal briefly disturbed an otherwise stable system. He was already a deeply polarizing political figure before the Bona Dea affair, and his public persona was inseparable from the broader fractures of the late Republic. Born into one of Rome’s most distinguished patrician families, Clodius deliberately rejected the traditional pathways of aristocratic advancement that emphasized gradual office-holding, senatorial consensus, and restrained public conduct. Instead, he cultivated notoriety, theatricality, and confrontation, presenting himself as a figure willing to violate decorum in order to expose what he framed as elite hypocrisy. This self-conscious rejection of aristocratic restraint made him unusually visible in Roman political culture and ensured that reactions to him were rarely neutral. Admiration and hostility clustered tightly around his name, creating a political identity that thrived on division rather than consensus.

Clodius’s political strategy depended on collapsing the distance between elite privilege and popular mobilization in ways that unsettled established norms. Unlike conservative aristocrats who relied on lineage, patronage, and gradual institutional advancement, he sought legitimacy through spectacle, street-level organization, and direct appeal to mass sentiment. His later adoption into a plebeian family, enabling his election as tribune of the plebs, was emblematic of this approach. The maneuver was legally permissible but widely regarded as cynical and opportunistic, an exploitation of procedural loopholes for naked political gain. Yet its success revealed something important about the late Republic. Roman political culture had become increasingly tolerant of formal distortion when it aligned with partisan interest. Clodius recognized that legality no longer functioned as a shared moral boundary. Institutions could be bent, repurposed, or hollowed out so long as sufficient political pressure shielded the result from reversal.

This political style made Clodius a lightning rod for broader anxieties about the Republic’s direction. To his opponents, he represented moral decay, lawlessness, and the erosion of aristocratic restraint. To his supporters, he embodied resistance to elite hypocrisy and senatorial domination. These opposing interpretations were not incidental. They were constitutive of his political identity. Clodius functioned less as a statesman than as a symbol through which competing visions of Roman legitimacy were expressed. Long before the Bona Dea trial, he had already become a figure for whom evidence would be interpreted through allegiance rather than evaluation.

The scandal did not introduce polarization into Clodius’s career. It intensified an existing condition that had already reshaped Roman political judgment. When accusations emerged, they did not encounter a neutral public weighing claims, testimony, and credibility. They encountered a political landscape already organized around trust and suspicion, loyalty and hostility. Those inclined to see Clodius as an agent of elite corruption found the charges self-evident and overdue. Those who viewed him as a victim of senatorial hostility dismissed the scandal as a manufactured attack designed to neutralize a popular threat. In this environment, the facts of the case mattered far less than what Clodius already represented to each camp. His persona absorbed the evidence rather than being reshaped by it, allowing belief to precede and determine interpretation.

Clodius illustrates a crucial feature of late Republican politics: individuals increasingly carried partisan meaning that preceded specific actions. Political identity hardened to the point that behavior no longer determined judgment. Instead, judgment determined how behavior was perceived. This inversion explains why the Bona Dea affair failed to produce consensus even in the presence of damning testimony. Clodius was not tried as a private citizen accused of sacrilege. He was tried as a partisan symbol in a system where symbols had begun to outweigh institutions. The trial became less a search for truth than a referendum on which version of Roman political reality would prevail.

Evidence, Testimony, and the Illusion of Proof

The case against Clodius was not built on rumor alone. Contemporary accounts indicate that substantial testimony placed him at the scene of the Bona Dea rites, contradicting the alibi he later advanced. Witnesses reported recognizing his voice, his presence, and the circumstances of his discovery within the household. These claims were not marginal or isolated. They emerged from multiple sources and were treated by many contemporaries as credible. In a political system still nominally committed to legal process, the evidentiary threshold for conviction appeared to have been met.

Clodius attempted to deflect these accusations through a carefully constructed alibi, asserting that he had been in a distant location at the time of the ceremony. This defense quickly unraveled under scrutiny. Testimony exposed inconsistencies in dates, travel time, and coordination, suggesting fabrication rather than error. Cicero played a central role in dismantling the alibi, presenting evidence that contradicted Clodius’s claims and framing the defense as an insult to the intelligence of the court. From a legal standpoint, the exposure of a false alibi would ordinarily have been decisive. It signaled not only guilt but contempt for judicial procedure. In earlier Republican trials, such a revelation would likely have ended the case. That it did not here reveals how far legal norms had already eroded beneath the surface of formal process.

Yet the accumulation of proof produced no corresponding shift in outcome. Rather than persuading undecided observers, testimony hardened existing positions. Those hostile to Clodius treated each new revelation as confirmation. His supporters dismissed the same evidence as manipulation or conspiracy. Proof did not resolve uncertainty. It reinforced allegiance.

The result was an illusion of legal process without its substance. Procedures were followed, witnesses heard, and arguments made, yet the trial no longer operated as a mechanism for determining truth. Evidence existed, but it could not compel agreement because the criteria for credibility had already fractured along partisan lines. In this environment, proof lost its coercive force. It could be presented, rebutted, and ignored without consequence. The appearance of legality remained intact, preserving the outward form of Republican justice, but its capacity to discipline power had evaporated. What survived was not law as judgment, but law as theater, performing neutrality while ratifying outcomes decided elsewhere.

Intimidation, Bribery, and the Engineering of Acquittal

The acquittal of Clodius cannot be understood as a legal anomaly produced by evidentiary uncertainty. It was the result of deliberate political engineering carried out in full view of the Roman public. Contemporary sources describe a trial environment shaped by intimidation, disorder, and the calculated erosion of judicial independence. Jurors were not insulated from external pressure but exposed to it, both physically and socially. The courtroom became an extension of the street, and the verdict reflected that reality. Legal procedure remained intact in form, but its outcomes were increasingly determined by forces operating outside the law.

Intimidation played a central role in shaping the conditions of judgment. Armed supporters of Clodius reportedly surrounded the proceedings, creating an atmosphere of threat rather than deliberation. Violence and the promise of violence were not aberrations in late Republican politics. They were tools increasingly deployed to influence assemblies, elections, and trials alike. In this context, jurors were asked not simply to weigh evidence but to calculate personal risk, reputation, and future safety. The question ceased to be whether Clodius was guilty. It became whether convicting him would expose an individual juror to retaliation, political isolation, or physical harm. Civic duty was displaced by survival calculus. This shift marked a profound transformation in Roman legal culture, where judgment no longer depended on reasoned evaluation but on the perceived balance of power outside the courtroom.

Bribery reinforced what intimidation initiated. Cicero and other contemporaries openly acknowledged that jurors were paid to secure acquittal. Financial inducement was neither subtle nor concealed, reflecting a broader normalization of corruption within Roman political culture. What distinguished the Bona Dea trial was not the presence of bribery, which had become distressingly common, but its effectiveness despite public awareness. Everyone knew the verdict had been purchased. That knowledge did not invalidate the outcome. It merely confirmed that procedural integrity no longer constrained political results.

The convergence of intimidation and bribery revealed the extent to which Roman courts had lost their status as neutral arbiters. Legal institutions still existed, but they no longer possessed independent authority. Verdicts followed power rather than law, and power was exercised through money, muscle, and partisan loyalty. This was not the collapse of legality in a dramatic sense. It was its hollowing out. The forms of justice remained recognizable, but their function had been repurposed to legitimize outcomes produced elsewhere.

The acquittal of Clodius signaled more than individual impunity. It demonstrated that accountability itself had become contingent, dependent not on evidence or law but on political alignment and coercive capacity. When intimidation and bribery could override proof without provoking institutional backlash, the Republic crossed a critical threshold. Law no longer disciplined political actors. It mirrored their relative strength. Acquittal did not imply innocence, just as conviction would no longer have guaranteed legitimacy. Justice survived as ritual rather than restraint, preserving the appearance of order while surrendering its substance. In this environment, scandal lost its corrective force precisely because power had learned how to absorb exposure without consequence.

“Everyone Knows”: Competing Truth Communities

In the aftermath of the Bona Dea trial, a striking rhetorical pattern emerges from the sources: a shared assertion of certainty paired with complete disagreement about reality. Cicero’s correspondence repeatedly conveys a sense that the facts of the case were obvious, even banal. Clodius’s guilt, in his view, required no argument. At the same time, Clodius’s supporters spoke with equal confidence in his innocence, treating the accusations as transparently false. The phrase “everyone knows” circulated on both sides, not as an invitation to consensus but as a declaration of tribal certainty. What fractured was not information but the audience capable of receiving it.

These opposed certainties reveal the emergence of competing truth communities within Roman political culture. Each group operated with its own criteria for credibility, legitimacy, and motive, criteria that were increasingly insulated from external challenge. Evidence presented by one side was not evaluated by the other but dismissed as inherently suspect, not because it was weak but because it originated from the wrong political camp. Testimony was accepted or rejected based on perceived allegiance rather than content. Courts, religious authorities, and elite opinion no longer functioned as shared reference points capable of settling disputes. Instead, they were absorbed into partisan narratives, stripped of independent authority, and repurposed as instruments of factional validation. Truth ceased to function as a common civic object and became a marker of belonging.

Within this fractured environment, scandal no longer performed its traditional role as a mechanism of exposure and correction. Rather than clarifying wrongdoing and compelling collective judgment, it intensified polarization and hardened identity boundaries. For Clodius’s enemies, the scandal confirmed elite moral collapse and justified continued hostility. For his supporters, it proved the existence of a conspiratorial establishment willing to fabricate charges to destroy a popular figure. Each interpretation fed on itself, reinforcing loyalty and deepening mistrust. The accumulation of evidence did not narrow disagreement. It widened it. Scandal functioned not as a corrective force but as an accelerant, transforming moral outrage into a renewable political resource.

The significance of this development lies in its structural consequences. Once political life fragments into incompatible truth communities, no amount of exposure can restore accountability. Verdicts lose meaning because they cannot command shared recognition. Acquittal satisfies only those already convinced, while condemnation persuades no one across the divide. The Bona Dea affair demonstrates that the late Republic’s crisis was not merely moral or legal but epistemic. Romans did not simply disagree about Clodius. They disagreed about how agreement itself could be reached. When “everyone knows” comes to mean “everyone like us knows,” scandal stops working, and the conditions for institutional collapse are quietly set in place.

Scandal as Tribal Signal, Not Accountability

Once political communities fracture along epistemic lines, scandal undergoes a functional transformation. It no longer operates as a mechanism for exposing wrongdoing or enforcing norms. Instead, it becomes a signal of group membership, a test of loyalty rather than a demand for judgment. In the late Roman Republic, the Bona Dea affair illustrates this shift with unusual clarity. The question was no longer whether Clodius had violated religious law. The question was which interpretation of the violation one was prepared to affirm publicly. Scandal ceased to discipline power and began to organize allegiance.

In this new configuration, moral outrage served less to condemn behavior than to affirm identity. Expressions of indignation were read not as ethical responses but as political declarations. To denounce Clodius was to align oneself with senatorial authority, elite norms, and traditional moral hierarchies. To dismiss the charges was to position oneself against perceived aristocratic conspiracy and in defense of popular autonomy. The content of the scandal mattered less than the stance one adopted toward it. What appeared as moral disagreement was, in practice, a sorting mechanism that clarified who belonged where within the political landscape.

This transformation also altered the incentives surrounding scandal in profound ways. Because exposure no longer threatened legitimacy across factions, it could be absorbed, neutralized, and even weaponized. Accusations provided opportunities to rally supporters, mobilize resentment, and reinforce narratives of persecution. Clodius’s acquittal did not rehabilitate him in the eyes of his enemies, nor did the evidence against him weaken loyalty among his allies. Instead, scandal became a renewable political resource, capable of sustaining attention and energy precisely because it could not be resolved. The persistence of controversy was not a sign of failure but of utility. So long as scandal remained unsettled, it continued to serve as a catalyst for mobilization, fundraising, and identity formation. Closure would have diminished its value.

The broader consequence was a fundamental inversion of accountability that reshaped Roman political life. In earlier Republican norms, scandal threatened exclusion, disgrace, or legal penalty. In the late Republic, scandal increasingly rewarded defiance and endurance. The more intense the accusations, the more clearly they marked the accused as a figure of partisan significance and resilience. Survival itself became a form of validation. This dynamic hollowed out the corrective function of public exposure altogether. When scandal operates as a tribal signal, accountability becomes structurally impossible because judgment is no longer shared. The Bona Dea affair demonstrates that the collapse of accountability does not require the disappearance of moral language or outrage. It requires only that moral language be repurposed to serve identity, loyalty, and power rather than restraint.

The Late Republic as a System without Neutral Arbiters

The failure of scandal to produce accountability in the Bona Dea affair was not an isolated malfunction. It reflected a deeper structural condition in the late Roman Republic: the disappearance of institutions capable of functioning as neutral arbiters. Courts, religious authorities, and political assemblies still existed, but their legitimacy had become contested rather than assumed. Each institution was increasingly interpreted through partisan expectation, so that outcomes were judged not by procedure or evidence but by alignment with factional interest. Authority remained visible, but trust in authority fractured.

Roman courts exemplified this breakdown with particular clarity. In theory, they were designed to adjudicate disputes through evidence, testimony, and legal reasoning, providing a common framework for resolving conflict. By the first century BCE, however, courts had become arenas of political struggle in which verdicts were often anticipated long before proceedings concluded. Jurors were selected, pressured, and rewarded with partisan outcomes in mind, and legal argument functioned less as a means of persuasion than as a ritualized performance. Decisions no longer settled disputes. They confirmed which faction possessed sufficient power to impose its will at that moment. When acquittal or conviction failed to command shared recognition, the court ceased to operate as an arbiter and became another contested space within an already polarized system.

Religious authority suffered a parallel erosion that further destabilized public judgment. Ritual offices, priesthoods, and sacred law had once provided a shared moral framework that could, at least in principle, transcend faction. By the time of the Bona Dea scandal, religious norms retained immense symbolic force but had lost their institutional coherence. Sacrilege could be invoked selectively, ignored strategically, or reframed as political persecution depending on circumstance. The gods themselves did not lose authority within Roman culture. Their interpreters did. Without trusted custodians capable of enforcing consistent standards, religious judgment could no longer stabilize political life. Instead, it supplied additional symbolic material for partisan conflict, intensifying division rather than resolving it.

Popular assemblies, often idealized as expressions of Roman collective will, also failed to provide neutral ground. Crowd dynamics increasingly reflected organized mobilization rather than deliberative judgment. Oratory functioned less as persuasion than as affirmation, reinforcing preexisting loyalties rather than testing claims. Mass participation did not produce consensus. It amplified division. Assemblies rewarded those who could command attention, intimidate opponents, or frame conflict in existential terms. As with courts and religious institutions, their authority depended on shared trust that no longer existed.

The absence of neutral arbiters created a system in which conflict could escalate without resolution. Every institutional decision was treated as provisional, illegitimate to those who lost and binding only to those who won. This condition did not produce immediate collapse. It produced paralysis punctuated by bursts of coercion. Power increasingly migrated away from institutions toward individuals and factions capable of enforcing outcomes directly. The late Republic did not fail because Romans abandoned law, religion, or politics. It failed because none of these domains retained the capacity to settle disagreement. Once no institution could compel belief across divisions, the Republic became a system governed by force, loyalty, and endurance rather than judgment.

Familiar Modern Partisan Reality

The dynamics exposed by the Bona Dea scandal feel uncomfortably recognizable because they are not confined to antiquity. Modern political systems, particularly those operating within mass media environments, exhibit similar patterns in which scandal no longer functions as a mechanism of accountability. Evidence circulates widely, testimony is publicly available, and institutional processes formally persist. Yet outcomes increasingly depend less on proof than on prior allegiance. As in the late Republic, exposure does not clarify judgment. It intensifies division.

Contemporary partisan politics often operates through the same logic of competing truth communities, now amplified by digital media ecosystems. Information is filtered through ideological networks that pre-structure belief before facts are encountered, shaping interpretation at the moment of exposure. Courts, investigative bodies, and journalistic institutions are no longer evaluated primarily on procedural integrity or evidentiary rigor but on perceived alignment with political identity. When an institution produces an unfavorable finding, it is dismissed as biased, corrupt, or illegitimate. When it produces a favorable one, it is celebrated as authoritative and courageous. The standard applied is not consistency but utility. Neutral arbiters continue to exist in form, but their capacity to compel trust across factions has steadily eroded.

In this environment, scandal increasingly serves as a loyalty test rather than a corrective. Public reaction to allegations functions as a signal of belonging. To accept evidence against a favored figure is framed as betrayal. To reject it, regardless of volume or credibility, is framed as solidarity. Moral language remains abundant, but it is deployed selectively. Outrage is not extinguished. It is redirected. As in Rome, scandal becomes a renewable resource precisely because it cannot be resolved. Its persistence sustains mobilization, fundraising, and identity formation.

The role of intimidation and delegitimation has also reemerged in modern form. While physical violence may be less overtly integrated into judicial proceedings, social, political, and rhetorical coercion shape public judgment. Witnesses are attacked, investigators are discredited, and unfavorable verdicts are reframed as illegitimate by definition. The objective is not to refute evidence but to undermine the authority of those presenting it. This strategy mirrors late Republican tactics, replacing open force with reputational warfare while achieving a similar effect: the insulation of power from accountability.

What is most striking is not the presence of corruption or dishonesty, which are constants in political life, but the normalization of epistemic fracture itself. Disagreement no longer concerns interpretation alone. It concerns the very possibility of shared evaluation. Different communities now operate with incompatible standards of credibility, expertise, and legitimacy. In such conditions, institutional outcomes lose their binding force. Acquittal convinces only those already convinced. Condemnation persuades no one outside the camp that demanded it. Legal judgments survive as procedural events, but their social authority collapses, leaving power increasingly untethered from collective consent.

The Roman comparison is instructive not because history repeats mechanically, but because structural conditions recur across time. The late Republic demonstrates how a political system can persist outwardly while losing its internal capacity for judgment. Scandal fails not because evidence is hidden or inaccessible, but because belief precedes evaluation. Once legitimacy comes first, facts become optional. The danger lies not in any single leader or controversy, but in a system where exposure no longer disciplines power. When scandal stops working, the problem is not ignorance. It is that truth itself has become partisan.

Conclusion: When Everyone Knows and Nothing Can Be Proven

The Bona Dea scandal endures not because of its lurid details or famous participants, but because it exposes a structural failure that remains politically relevant. The trial of demonstrates how a system can retain the outward forms of legality while losing its capacity to produce shared judgment. Evidence was presented, testimony heard, procedures followed. Yet none of it mattered in the way Republican theory assumed it should. The problem was not insufficient proof. It was the absence of a political community capable of agreeing on what proof meant.

Once belief precedes evaluation, scandal loses its corrective power in fundamental ways. Accusations no longer function as tests of conduct but as affirmations of identity, signaling loyalty rather than demanding judgment. Verdicts do not settle disputes. They merely sort audiences into camps that were already formed. In such an environment, truth becomes retrospective, assembled after allegiance rather than discovered through process. This explains how Cicero could speak as though guilt were obvious while Clodius’s supporters spoke with equal certainty of innocence. Both positions were internally coherent within their respective truth communities, and neither could persuade the other because persuasion itself depended on shared standards that no longer existed. When everyone knows, nothing can be proven in a way that binds across division.

The late Roman Republic illustrates how dangerous this condition becomes over time. Institutions depend not only on procedure but on trust in procedure. When courts, religious authorities, and assemblies lose the ability to compel recognition across factional lines, power migrates elsewhere. It moves toward those capable of enforcing outcomes through loyalty, intimidation, or endurance. Scandal, once a threat to legitimacy, becomes a resource for those skilled at surviving it. Accountability dissolves not through ignorance, but through the normalization of disbelief.

The lesson of the Bona Dea affair is not about Rome alone. It is about the fragility of any political system that assumes exposure guarantees consequence. When shared standards of credibility collapse, no amount of evidence can restore them. Scandal stops working not because wrongdoing disappears, but because judgment itself fractures. A society can continue to argue, accuse, investigate, and prosecute indefinitely while drifting further from resolution. The danger is not merely cynicism or fatigue. It is the quiet replacement of judgment with power, where endurance, intimidation, and allegiance matter more than proof, and where the appearance of accountability survives long after its substance has vanished.

Bibliography

- Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. Religions of Rome, Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Cicero. Letters to Atticus. Translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- —-. Pro Caelio. Translated by R. Gardner. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958.

- Engel, Niklas. “Corruption and the Public Sphere in Late Republican Rome.” Cultural History 13:1 (2024): 12-28.

- Flower, Harriet I. Roman Republics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Gruen, Erich S. The Last Generation of the Roman Republic. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

- Lintott, Andrew. The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- —-. Violence in Republican Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown, 2018.

- Millar, Fergus. The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998.

- Morstein-Marx, Robert. Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Müller, Jan-Werner. What Is Populism? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

- Rawson, Elizabeth. Intellectual Life in the Late Roman Republic. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985.

- Riggsby, Andrew M. Roman Law and the Legal World of the Romans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Rosenfeld, Sophia. Democracy and Truth: A Short History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

- Scheid, John. An Introduction to Roman Religion. Translated by Janet Lloyd. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003.

- Steel, Catherine. The End of the Roman Republic 146 to 44 BC: Conquest and Crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Sunstein, Cass R. Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

- Tatum, W. Jeffrey. “Cicero and the Bona Dea Scandal.” Classical Philology 85:3 (1990): 202-208.

- —-. Patrician Tribune: Publius Clodius Pulcher. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

- Thompson, John B. Political Scandal: Power and Visibility in the Media Age. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000.

- Wick, David P. “Augusts – the Engineering of Belief & the Pax Deorum: Part 2 in a Serial Study of the Pax Deorum.” Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies 5:2 (2019): 79-88.

- Yakobson, Alexander. Elections and Electioneering in Rome. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.04.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.