What makes Aristotle’s logic especially dangerous is its respectability. When authority borrows the voice of nature, it speaks with a calm that disarms moral resistance.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Dehumanization without Hatred

Dehumanization is often imagined as the language of rage. It is associated with slurs, violence, and open contempt, the kind of speech that announces its cruelty without disguise. Yet historically, the most durable forms of dehumanization have not relied on hatred at all. They have emerged instead from calm, authoritative reasoning that classifies, orders, and explains human difference as a matter of nature rather than choice. In these cases, domination does not appear as an act imposed by power, but as a condition discovered by reason. Violence is not denied, but it is displaced, reinterpreted as necessity, care, or order.

Dehumanization is a political method that operates most effectively when it is allegedly respectable. Rather than focusing on propaganda, emotional incitement, or mass psychology, it centers on elite intellectual frameworks that transform exclusion into inevitability. When authority speaks in the language of nature, hierarchy becomes morally self-justifying. Those excluded are not punished for who they are but governed according to what they are said to be. The humiliation that follows is not framed as cruelty, but as alignment with reality itself.

Aristotle stands at the center of this argument. In Politics, he offers one of the clearest early articulations of naturalized human hierarchy, most famously through his concept of the “natural slave.” This was not marginal rhetoric or polemical exaggeration, nor was it a passing concession to custom. It was a systematic philosophical claim grounded in Aristotle’s broader account of reason, purpose, and the proper ordering of the polis. By tying political capacity to rational deliberation, Aristotle created a scale of humanity that appeared descriptive rather than normative. Those placed lower on this scale were not wronged by exclusion, because exclusion followed logically from their nature. Domination ceased to look like an ethical problem and instead became a matter of appropriate placement within an already ordered world.

Aristotle’s significance lies not only in what he argued, but in how he argued it. His language is measured, his logic internally coherent, and his conclusions presented as observations about human reality rather than choices made by power. This rhetorical posture is crucial. By framing hierarchy as something revealed by philosophy rather than enforced by authority, Aristotle insulated domination from moral scrutiny. Rule became a form of care, obedience a form of fulfillment, and inequality a condition of harmony rather than injustice. Aristotle was not as an aberration to be dismissed but a foundational philosopher who exposes a recurring political logic. When authority uses “nature” to excuse humiliation, dehumanization no longer needs hatred to function. It requires only credibility, intellectual legitimacy, and the power to define what counts as human enough to rule, and what does not.

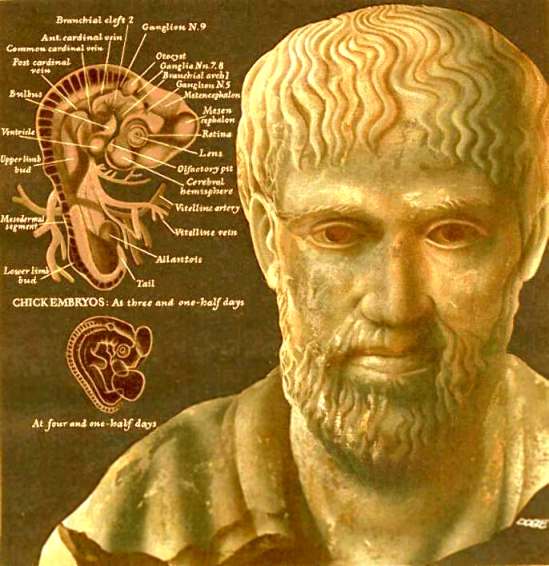

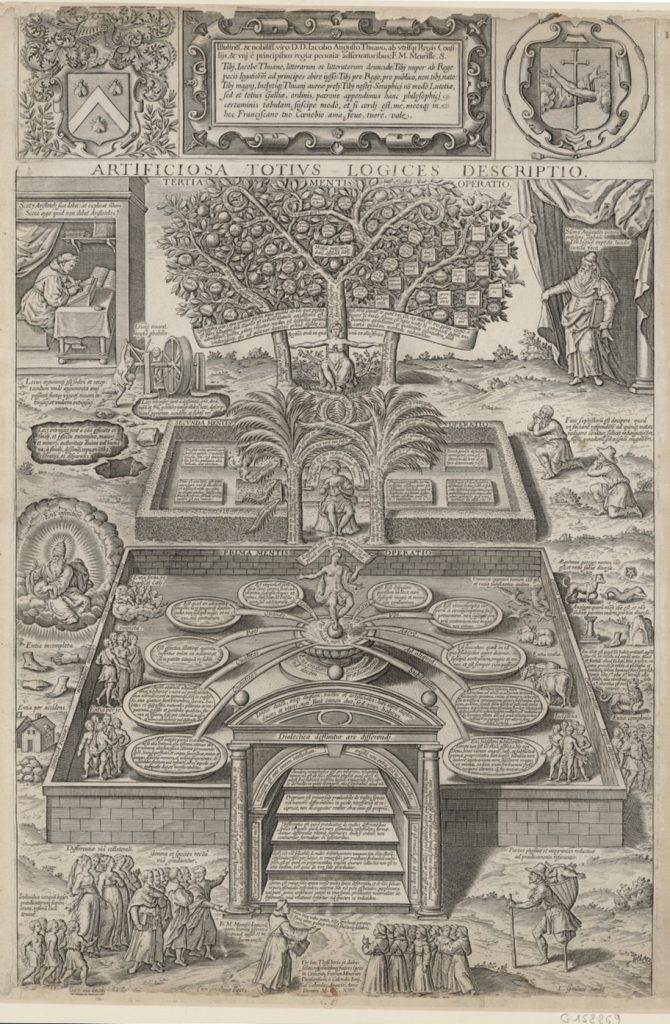

Aristotle’s Political Biology: Reason, Capacity, and the Hierarchy of Souls

Aristotle’s political thought begins with a biological and teleological understanding of the human world, one in which nature is neither accidental nor morally neutral. For Aristotle, nature is purposive. Everything that exists has an end toward which it is ordered, and its excellence is measured by how fully it realizes that end. Human beings, within this framework, are distinguished not simply by social convention but by an intrinsic capacity for reason, specifically the ability to deliberate about the good and to participate in rational judgment. Politics is not an artificial arrangement imposed upon humans by force or contract, but the natural expression of their highest function. This premise allows Aristotle to present political hierarchy not as a contingent system of power, but as the proper unfolding of human differentiation itself. Inequality is built into the structure of the world before any laws are written or institutions formed.

Central to this argument is Aristotle’s distinction between possessing reason and merely apprehending it. In Politics, he argues that some individuals are capable of rational deliberation, while others can recognize reason in another without fully exercising it themselves. This distinction becomes the basis for his theory of natural slavery. Those who lack the deliberative faculty necessary for self-rule are said to benefit from being ruled by others who possess it more fully. What is at first glance a political judgment is presented as an anthropological fact. Hierarchy follows from difference, not from force.

Aristotle’s conception of the soul reinforces this structure and gives it psychological depth. Drawing on his broader account of human nature, he divides the soul into rational and non rational parts, assigning normative significance to this division. The rational element is associated with judgment and foresight, while the non-rational is linked to appetite, bodily labor, and the execution of commands. Aristotle then maps this internal hierarchy outward onto social relations. Just as reason ought to rule appetite within the individual, so too should those endowed with rational capacity rule those whose role is primarily physical or instrumental. Political domination is analogized to self-mastery, and subordination becomes a functional necessity rather than a moral problem. The polis mirrors the soul, and hierarchy appears as order rather than coercion.

This move is decisive because it removes domination from the realm of ethical conflict altogether. If rule is an expression of nature, then resistance ceases to be a claim about injustice and becomes instead a symptom of disorder. Aristotle does not deny that force may be used, but force is rendered secondary and almost incidental. What matters is not the act of domination itself, but the prior classification that makes domination appear appropriate. Once individuals are assigned to their natural category, their political fate is effectively sealed. Exclusion from citizenship, autonomy, or deliberation no longer requires ongoing justification because it is presented as the logical outcome of human variation rather than an imposed deprivation.

Importantly, Aristotle does not present this hierarchy with hostility or contempt. His tone is measured and often paternal. The natural slave is not vilified but described as incomplete, dependent, and in need of guidance. This absence of animus is not incidental. By stripping domination of emotional intensity, Aristotle makes it more credible and more enduring. The harm inflicted by exclusion is reframed as benefit, and subordination is recast as participation in a higher rational order.

The result is a political biology in which inequality is stabilized by reason itself. Aristotle’s hierarchy of souls does not merely justify existing social arrangements; it supplies a durable intellectual framework in which hierarchy appears inevitable, benevolent, and morally unremarkable. Dehumanization here does not operate through the outright denial of humanity, but through graded inclusion within it. Some are fully human in the political sense, capable of ruling and deliberating, while others are human only instrumentally, valued for their labor and obedience. This distinction does the work of power quietly and efficiently, allowing domination to function without ever naming violence as its source.

From Domination to Care: How Aristotle Removes Violence from Rule

Aristotle’s most consequential move is not the initial classification of human beings into hierarchical categories, but the moral reframing that follows from it and stabilizes those categories over time. Once hierarchy is established as natural, the exercise of power no longer appears as domination at all. Rule is redescribed as care, supervision, or guidance, a relationship oriented toward the good of the ruled rather than the advantage of the ruler. In Politics, Aristotle repeatedly insists that ruling the natural slave benefits both parties, because it aligns each with their proper function within the social whole. The master is said to provide reason where it is lacking, while the slave provides labor where reason alone is insufficient. Violence does not disappear in practice under this model, but it disappears conceptually. It is no longer the defining feature of rule, only a regrettable contingency that arises when natural order is resisted or improperly understood.

This reframing depends on Aristotle’s teleological worldview. Because every being has a natural end, fulfilling that end is itself a form of good. For those deemed incapable of rational self-direction, being ruled is not a deprivation but a realization of purpose. Obedience becomes a mode of flourishing rather than a loss of freedom. By this logic, the master who rules well does not impose his will arbitrarily but acts as an instrument of nature, helping the ruled achieve what they cannot achieve alone. Domination is morally laundered through function. The political relationship is stripped of conflict and recast as complementary cooperation.

This transformation removes the need to confront violence as a moral problem. If rule is justified by nature, then coercion is no longer the central issue. What matters instead is whether rule is properly aligned with natural capacity. Aristotle does not deny that force may be used to maintain order, but force is treated as secondary, almost incidental. The real work is done earlier, at the level of classification. Once individuals are defined as naturally subordinate, the question of whether they consent or resist loses normative weight. Resistance signals misalignment with nature, not a claim to justice.

This logic also allows Aristotle to collapse the distinction between domination and benevolence in a way that is politically decisive. Because the ruler is presumed to possess superior rational capacity, his authority is framed as inherently corrective and stabilizing rather than self-interested. Even harsh treatment can be rationalized as necessary discipline, analogous to the governance of appetite by reason within the soul. The language of care absorbs the realities of coercion, recasting them as unfortunate but necessary aspects of moral supervision. The ruled are not wronged by their subordination, because subordination is presented as the condition under which they are most fully themselves. Humiliation, in this framework, is not recognized as harm at all. It is simply the experiential consequence of occupying one’s assigned place within a rational order.

The effect of this argument is to render violence politically invisible, not by denying its existence but by depriving it of moral significance. By redefining domination as care, Aristotle creates a model in which power can operate continuously without appearing violent, even to those who wield it. Authority no longer needs to justify itself through fear, spectacle, or brute force, because it speaks instead in the language of necessity, function, and benefit. This is the deeper danger of naturalized hierarchy. When rule is framed as fulfillment rather than imposition, domination becomes morally self-sustaining. Violence does not vanish under such systems, but it no longer needs to announce itself as violence at all.

Respectable Dehumanization: Why Aristotle’s Model Endures

The endurance of Aristotle’s model of hierarchy lies not in its specific claims about ancient slavery, but in the structure of reasoning it establishes. His arguments survive because they do not rely on overt cruelty, religious dogma, or mythic authority. Instead, they present domination as the outcome of rational assessment. By grounding hierarchy in capacity, function, and nature, Aristotle supplies a framework that can be detached from its original context and reapplied wherever inequality seeks moral legitimacy. The content may change, but the form remains strikingly stable.

One reason for this durability is tone. Aristotle does not write as a polemicist or an ideologue. His language is calm, analytic, and explanatory, aimed at understanding rather than persuasion. Hierarchy is not celebrated with triumph nor enforced with threats. It is simply described as how the world works when properly understood by a rational observer. This rhetorical restraint is not incidental. It grants the argument a sense of inevitability and seriousness, especially among elites who see themselves as custodians of reason rather than wielders of power. Dehumanization delivered without anger appears thoughtful rather than violent, measured rather than coercive and more difficult to challenge on moral grounds. It does not provoke outrage as much as acquiescence.

Equally important is the way Aristotle’s framework shifts moral evaluation away from power and toward classification. Once inequality is explained as the result of natural difference, ethical attention moves from the act of ruling to the accuracy of the underlying assessment. The key question is no longer whether domination is justified, but whether individuals have been correctly identified as capable or incapable of rational self-direction. This move fundamentally narrows the space for moral critique. If the categories themselves are accepted as legitimate and objective, then domination follows automatically, without requiring renewed justification at each stage. Political exclusion becomes a technical matter, not a moral one, and injustice is redefined as misclassification rather than subordination itself.

Aristotle’s model also endures because it allows rulers to imagine themselves as benevolent even while enforcing exclusion. Authority becomes a form of responsibility rather than privilege. Those who rule do so not because they desire power, but because they are said to possess the capacities necessary to guide others. This self image is politically powerful. It permits domination to coexist with moral self regard, insulating rulers from the charge of cruelty. The harm experienced by the ruled is reframed as unfortunate but necessary, or even as beneficial in the long term.

Another source of durability lies in the model’s adaptability. Aristotle’s hierarchy does not depend on a single marker such as birth, ethnicity, or legal status. It depends instead on assessments of rationality, competence, and moral capacity, categories that can be redefined across time and culture. This flexibility allows the structure to persist even as its justifications evolve. New sciences, moral theories, or administrative languages can be layered onto the same underlying logic without altering its basic function.

Aristotle’s model endures because of its ability to make domination appear unremarkable. By embedding hierarchy within the ordinary operations of reason, it strips power of spectacle and emotional charge. Dehumanization becomes procedural rather than dramatic, administered through assessments, standards, and criteria that claim neutrality and expertise. In this form, power does not need to announce itself loudly or violently. It operates quietly, through explanation, normalization, and the authority to define what counts as full participation in the human community. The absence of visible cruelty is precisely what allows this form of domination to persist with such stability.

When “Nature” Fails: Exposure, Resistance, and Moral Reversal

Aristotle’s framework depends on the credibility of nature as an explanatory authority, one capable of settling political questions before they are asked. As long as hierarchy appears grounded in stable distinctions of capacity and purpose, domination can present itself as order rather than imposition. Nature functions as a moral shield, absorbing responsibility, and dispersing blame. The moment those distinctions are questioned, however, the entire architecture begins to strain. What had seemed inevitable starts to look contingent. What had appeared benevolent begins to resemble control. The exposure of naturalized hierarchy does not initially require a wholesale rejection of rule itself. It begins more quietly, with the recognition that “nature” has been doing political work all along, translating power into description and coercion into necessity.

This exposure often occurs when those assigned to subordinate categories demonstrate capacities they were said not to possess. The claim that some lack deliberative reason collapses when deliberation is visibly exercised, whether through speech, organization, or moral argument. At that point, the classification that once justified domination can no longer sustain itself as descriptive. It must either be revised, tightened, or defended through means that reveal its coercive core. What was once framed as alignment with nature now demands enforcement, and the quiet authority of reason gives way to the visible assertion of power.

Resistance, in this sense, does not begin as rebellion but as denaturalization, a direct challenge to the categories that made domination appear self evident. It contests the standards by which rationality, capacity, and fitness have been defined, rather than merely refusing obedience within those definitions. By disputing the criteria through which humanity has been graded, resistance forces domination back into the ethical realm it sought to escape. Questions that naturalized hierarchy had rendered irrelevant return with force: who decides, by what authority, and to whose benefit? Once these questions surface, humiliation can no longer be dismissed as the experience of occupying one’s proper place. It must be confronted as harm inflicted by an imposed order that claimed inevitability only by masking its own contingency.

This moment produces a moral reversal. Practices once defended as care are reclassified as control. Guidance is recognized as surveillance, discipline as punishment, and exclusion as deprivation rather than fulfillment. The ruler’s claim to benevolence becomes unstable because benevolence requires recognition and consent, not merely classification. Violence, previously rendered invisible by the language of nature, reenters political consciousness as violence. It is no longer incidental or unfortunate, no longer a failure of implementation. It is revealed as structural and deliberate, sustained precisely by the denial that it was violence at all.

The failure of naturalization reveals the fragility of respectable dehumanization more clearly than overt revolt ever could. Aristotle’s model is powerful because it avoids spectacle and cruelty, substituting calm explanation for force. Yet this strength becomes a vulnerability when its foundational assumptions are exposed. Once hierarchy is understood as a political choice rather than a natural fact, its moral immunity dissolves. Domination must then either retreat, reconfigure itself under new justifications, or defend its authority without the cover of inevitability. When nature can no longer speak convincingly for power, authority is forced to confront the humiliation it once rendered invisible, and to answer for the violence it claimed never to commit.

Conclusion: When Authority Borrows the Voice of Nature

Aristotle’s enduring significance lies not in the historical particulars of ancient slavery, but in the political logic he helped crystallize and normalize within the language of reason itself. By grounding hierarchy in nature, capacity, and purpose, he offered a way to make domination appear reasonable, benevolent, and morally unremarkable to those who exercised it. Power did not need to justify itself as power. It could present itself instead as insight, as fidelity to an already ordered world that philosophy merely revealed rather than constructed. This transformation did not eliminate violence, but it displaced it. Coercion was relocated behind classification, moral assessment, and claims about function, rather than enacted openly as force. The result was a form of dehumanization that could operate without hatred, spectacle, or explicit cruelty, precisely because it appeared to require none of those things to sustain itself.

What makes this logic especially dangerous is its respectability. When authority borrows the voice of nature, it speaks with a calm that disarms moral resistance. Exclusion becomes technical rather than ethical. Humiliation becomes incidental rather than inflicted. Those who suffer under such systems are not described as victims of domination, but as occupants of roles they are said to fit. The absence of visible malice allows both rulers and observers to mistake stability for justice. Harm persists, not because it is denied, but because it is redescribed as necessity.

The exposure of this logic reveals that the most consequential political struggles often turn not on policy or leadership, but on classification itself and the authority to define it. As long as categories of capacity, rationality, or fitness remain unquestioned, domination can reproduce itself indefinitely while claiming neutrality and moral seriousness. Aristotle’s framework shows how deeply this dynamic can embed itself within respectable thought, making inequality appear as an outcome of reason rather than a choice enforced by power. Resistance begins when those categories are challenged, when “nature” is shown to be a language of authority rather than an external arbiter. At that point, domination loses its moral insulation. It must either abandon its claims to inevitability, reconstitute itself under new classificatory schemes, or defend itself openly as coercion rather than care.

The lesson that emerges from Aristotle’s case is not confined to antiquity. Whenever authority presents hierarchy as natural, whenever exclusion is framed as care, and whenever humiliation is justified as order, the same logic is at work. Dehumanization does not announce itself as cruelty. It arrives instead as reason, explanation, and concern. To recognize this is not to reject reason itself, but to refuse its conscription into the service of domination. When authority speaks in the language of nature, the task of political judgment is to ask whose nature is being described, who is empowered to describe it, and who bears the cost of that description.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958.

- —-. On Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1970.

- —-. Responsibility and Judgment. New York: Schocken Books, 2003.

- Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Terence Irwin. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1999.

- —-. Politics. Translated by C. D. C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1998.

- Arnhart, Larry, “The Darwinian Biology of Aristotle’s Political Animals.” American Journal of Political Science 38:2 (1994), 464-485.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. Modernity and the Holocaust. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Broadie, Sarah. “Nature, Craft and Phronesis in Aristotle.” Philosophical Topics 15:2 (1987), 35-50.

- Dobbs, Darrell. “Natural Right and the Problem of Aristotle’s Defense of Slavery.” The Journal of Politics 56:1 (1994), 69-94.

- Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things. New York: Vintage Books, 1966.

- Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum, 1968.

- Garnsey, Peter. Ideas of Slavery from Aristotle to Augustine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Haslam, Nick. “Dehumanization: An Integrative Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 10, no. 3 (2006): 252–264.

- Nussbaum, Martha. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Schofield, Malcolm. Saving the City: Philosopher Kings and Other Classical Paradigms. London: Routledge, 1999.

- Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990.

- Taylor, Charles. Modern Social Imaginaries. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

- Turner, Christopher. “Trouble in Paradise: Aristotle’s Ideal Polis & Political Exclusion.” Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia 76:1 (2020), 209-236.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society. Translated by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.10.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.