When walls become systems, they redefine the architecture of exchange. Reversing them requires more than lowering duties; it requires rebuilding trust.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

The Shock of 1929 and the Search for Protection

The global economic order that unraveled after 1929 had been built upon foundations that appeared durable but were structurally brittle. During the 1920s, international trade expanded under the constraints of the gold standard, a system that required governments to maintain currency convertibility and fiscal discipline in order to sustain fixed exchange rates. Capital moved with relative fluidity across borders, American lending underwrote European recovery, and industrial production surged in several advanced economies. Yet this apparent stability masked deep imbalances: unresolved war debts from the First World War, German reparations obligations, fragile banking systems, agricultural overproduction, and uneven credit expansion. The system depended heavily on continued confidence and on American financial primacy. When the U.S. stock market collapsed in October 1929, the shock reverberated through interconnected financial networks that lacked effective mechanisms for coordinated crisis response. What had seemed an integrated order revealed itself as a chain of mutual vulnerabilities.

The contraction that followed was not merely a cyclical downturn but a systemic unraveling. As credit tightened and banks failed, global demand plummeted. International lending contracted sharply, particularly from the United States to Europe and Latin America, triggering cascading defaults and currency instability. Falling commodity prices devastated export-dependent economies, undermining state revenues and intensifying social strain. Industrial output declined precipitously in the United States and spread across Europe and beyond. The gold standard, rather than stabilizing currencies, transmitted deflationary pressure across borders, forcing governments to defend parities through austerity and monetary contraction. Nations that remained on gold often deepened domestic recession in order to preserve exchange commitments. What had been promoted as a guarantor of stability became an amplifier of crisis.

Political pressure mounted quickly. Industrialists demanded relief from foreign competition. Agricultural sectors, already suffering from price collapse, lobbied for tariff protection. Legislators faced electorates anxious about unemployment and business failures. In democratic systems, the appeal of protective measures proved powerful. Tariffs promised visible defense of domestic producers, even if their broader systemic consequences were uncertain. Economic nationalism began to supplant faith in multilateral cooperation. Governments increasingly interpreted the crisis through a domestic lens rather than a systemic one.

The erosion of confidence in open trade frameworks was compounded by the absence of effective international leadership. Unlike later crises that would see coordinated responses through institutions such as the International Monetary Fund or World Bank, the early 1930s lacked comparable structures. Efforts at international coordination faltered amid competing national priorities and currency instability. As countries struggled to defend gold reserves and stabilize budgets, cooperative solutions receded. Economic policy became defensive rather than integrative.

By the early 1930s, the search for protection had hardened into a defining principle of economic governance across much of the industrialized world. Tariffs, quotas, exchange controls, and preferential agreements were no longer temporary expedients but increasingly institutionalized responses to perceived vulnerability. Policymakers framed these measures as necessary shields against foreign instability and unfair competition, yet each act of protection altered the incentives facing trading partners. The integrated trade system of the 1920s did not collapse in a single legislative act or dramatic conference failure. It fractured through successive national decisions taken under the pressure of crisis, each one narrowing the space for cooperative recovery. The shock of 1929 initiated a chain reaction in which defensive economic nationalism became self-reinforcing, setting the stage for a decade defined by fragmentation rather than reintegration.

Smoot–Hawley and American Tariff Escalation (1930)

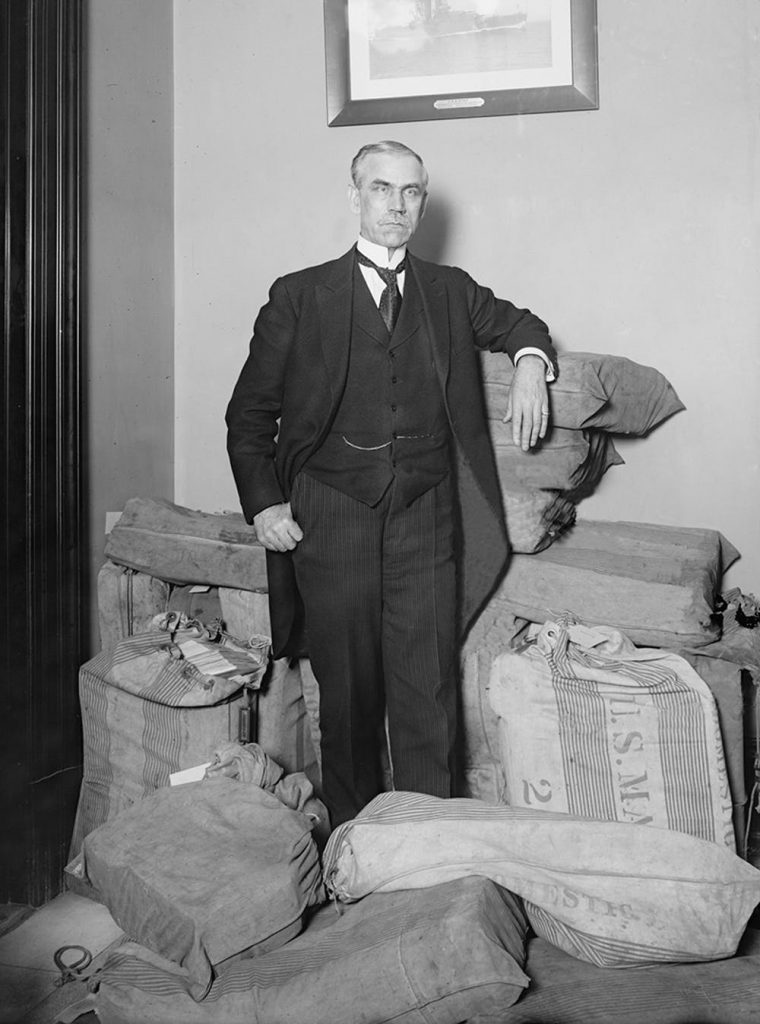

The Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 marked a decisive turn in American economic policy at a moment of mounting global fragility. Sponsored by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willis C. Hawley, the legislation substantially increased tariff rates on thousands of imported goods. Initially framed as relief for struggling agricultural producers, the bill expanded under congressional revision to encompass a wide array of industrial products. The United States, still the world’s largest economy and a central creditor nation, moved to institutionalize protectionism at the core of the global trading system. What had been debated as a sectoral adjustment became a sweeping revision of American trade posture.

The political logic behind the legislation reflected domestic pressures intensified by the Depression and by structural tensions dating back to the 1920s. Farm incomes had suffered from chronic overproduction and falling commodity prices well before the stock market crash, and agricultural constituencies demanded federal action to stabilize livelihoods. Industrial producers, facing declining orders and rising unemployment, feared intensified foreign competition as global demand contracted. Lawmakers responded to sustained lobbying from both sectors, each seeking tariff insulation as a visible demonstration of governmental protection. The tariff schedule expanded through congressional bargaining, with representatives inserting duties tailored to local industries in exchange for support. Although over one thousand economists signed a public petition urging President Herbert Hoover to veto the bill, warning that tariff escalation would provoke retaliation and further contract trade, Congress proceeded with broad bipartisan backing. Hoover, cautious but politically constrained, ultimately signed the measure into law in June 1930. The act reflected not only economic calculation but the cumulative weight of domestic political incentives operating under crisis conditions.

International reaction was swift. Canada, the United States’ largest trading partner at the time, imposed retaliatory tariffs on American goods. European countries followed with their own protective measures, adjusting duties or adopting quota systems to shield domestic industries. Rather than stabilizing American producers, the tariff escalation contributed to a cycle of countermeasures that reduced overall trade volumes. Export industries in the United States soon faced shrinking foreign markets, undermining the intended protective effect. Retaliation did not remain rhetorical; it became embedded in policy.

The contraction in global trade during the early 1930s cannot be attributed solely to Smoot–Hawley, as deflation, currency instability, banking failures, and collapsing investment also played decisive roles. Nevertheless, the act carried symbolic and practical weight disproportionate to any single tariff schedule. By raising barriers at the center of the world economy, the United States signaled a retreat from the integrative aspirations of the postwar decade. Other governments interpreted this shift as both precedent and warning. If the leading creditor nation embraced protection, smaller economies faced intensified pressure to defend domestic markets. The institutionalization of protectionism by a central economic power altered expectations about the durability of liberal trade commitments and accelerated defensive policymaking elsewhere. Tariff escalation interacted with broader monetary and financial breakdowns, reinforcing a spiral of fragmentation.

Smoot–Hawley stands as a structural inflection point. It did not single-handedly cause the Great Depression, but it intensified fragmentation within an already strained system. When a central actor raises tariff walls, peripheral actors adapt defensively. Trade partners diversify markets, form preferential agreements, or construct retaliatory regimes. The result is not restored leverage but reorganization. The American decision to escalate tariffs in 1930 contributed to the hardening of economic blocs that would characterize the remainder of the decade.

Britain and the Turn to Imperial Preference (Ottawa Agreements, 1932)

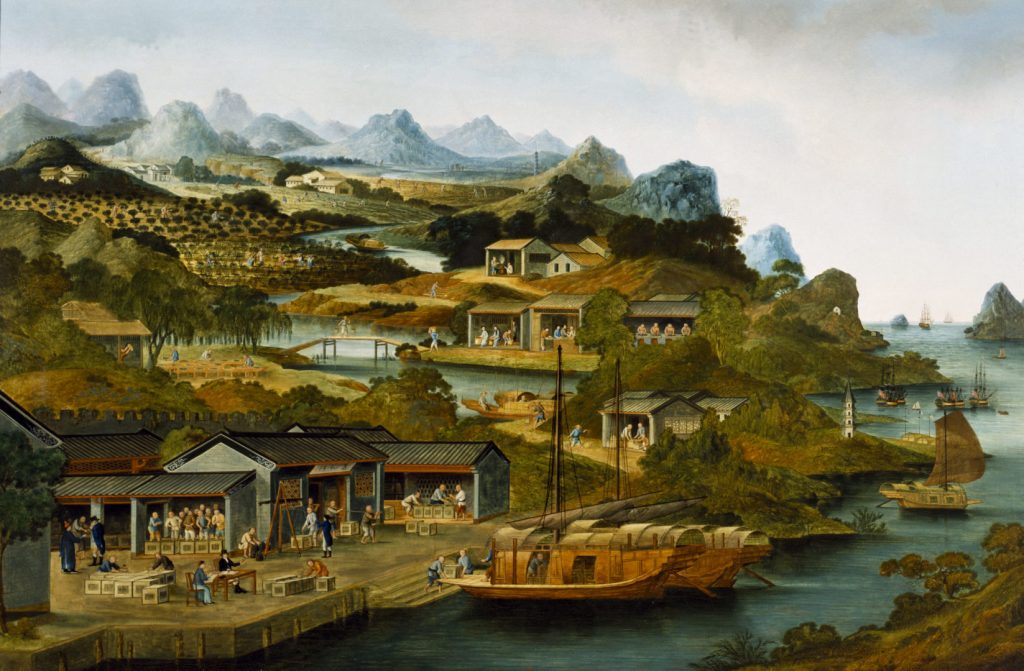

Britain entered the Great Depression with a long-standing ideological commitment to free trade, a doctrine that had defined its commercial identity since the repeal of the Corn Laws in the mid-nineteenth century. For decades, British policymakers had defended open markets as both an economic necessity and a civilizational principle, reflecting the country’s position as a global trading hub and financial center. Yet by the early 1930s, economic contraction, industrial stagnation, and rising unemployment strained this orthodoxy. The collapse of world demand, combined with persistent trade imbalances and the mounting pressures of currency defense under the gold standard, exposed vulnerabilities in Britain’s economic structure. The abandonment of the gold standard in September 1931 marked a decisive break with traditional monetary policy and symbolized the erosion of confidence in established frameworks. Within this context of uncertainty, policymakers increasingly viewed imperial consolidation as a stabilizing alternative. Rather than restoring multilateral openness, Britain turned toward preferential arrangements within its empire, reframing commercial policy around imperial cohesion.

The Ottawa Conference of 1932 institutionalized this shift. Representatives from Britain and its dominions negotiated agreements granting preferential tariff treatment to goods traded within the Empire. British markets provided advantages to colonial and dominion producers, while imperial partners extended reciprocal preferences to British exports. The objective was to strengthen internal economic cohesion and reduce dependence on volatile external markets. Imperial Preference did not eliminate trade with non-empire states, but it embedded discrimination within tariff schedules, privileging imperial exchange over broader multilateral commerce.

This strategy reflected both economic calculation and political symbolism. Economically, imperial preference aimed to secure stable markets for British industry and agriculture at a time when global demand was unreliable. Politically, it reinforced the notion of the Empire as an integrated economic community capable of weathering external shocks. By tightening intra-imperial trade links, Britain sought to transform geopolitical hierarchy into economic resilience. The Empire became not merely a political structure but a protective commercial bloc.

Yet imperial consolidation contributed to wider fragmentation. As Britain redirected trade inward, external partners adjusted accordingly. Countries excluded from preferential treatment intensified their own protectionist measures or sought alternative alliances. Rather than restoring the liberal trading system of the prewar era, imperial preference signaled the normalization of bloc-based trade policy. Multilateral negotiation gave way to selective reciprocity, and discrimination replaced universal access. Economic relations increasingly followed geopolitical alignments.

Britain’s shift illustrates how crisis can transform long-standing principles into instruments of strategic retrenchment. Faced with instability, policymakers abandoned universal free trade in favor of imperial preference as a mechanism for preserving domestic employment and imperial unity. The decision did not amount to autarky, but it restructured Britain’s economic orientation toward a closed circle of favored partners. This inward turn reinforced the segmentation of global commerce into competing blocs. What had once been the leading advocate of open markets became a central architect of preferential discrimination. Imperial Preference did not simply shield Britain from the Depression; it contributed to the institutionalization of economic nationalism across the interwar system, accelerating the fragmentation already underway.

Retaliation and the Hardening of Economic Blocs

Tariff escalation in the early 1930s did not unfold in isolation. As the United States raised duties and Britain consolidated imperial preference, other states recalibrated defensively. Retaliation became embedded within national policy frameworks rather than limited to temporary countermeasures. Governments imposed quotas, exchange controls, and bilateral clearing arrangements to manage trade under conditions of scarcity and currency instability. The cumulative effect was the gradual erosion of multilateral exchange in favor of segmented economic spheres.

In continental Europe, Germany pursued a strategy of bilateral trade agreements and clearing systems designed to conserve foreign exchange and prioritize strategic imports. Rather than relying on open markets, the German government negotiated state-to-state arrangements that tied exports and imports through managed accounts, often denominated in clearing currencies rather than convertible gold. These agreements allowed Germany to trade without drawing down scarce hard currency reserves, particularly as global capital markets remained unstable. By structuring trade around negotiated quotas and state supervision, Berlin gained leverage over smaller economies in Eastern and Southeastern Europe, whose access to German markets became politically conditioned. Economic exchange moved from market-mediated flexibility to politically mediated allocation. Commercial relationships increasingly reflected power asymmetries rather than price signals alone.

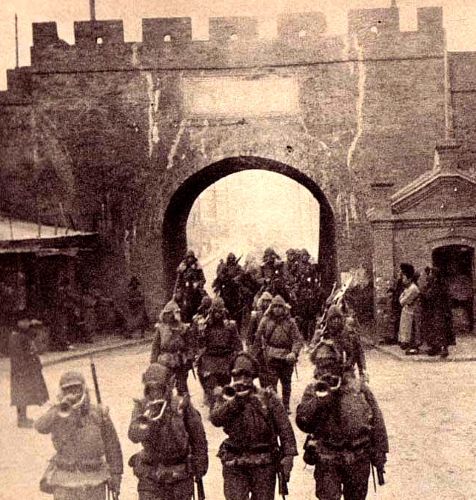

Japan adopted a comparable logic in East Asia, though with a stronger territorial dimension. Faced with limited domestic access to essential raw materials and constrained by declining global demand, Japanese policymakers sought greater economic autonomy through regional consolidation. The occupation of Manchuria in 1931 and the subsequent development of the so-called “Manchukuo” economic zone provided access to coal, iron, and agricultural resources. Trade within this sphere was increasingly structured to serve Japanese industrial and military priorities. Rather than relying on multilateral trade governed by price competition, Japan cultivated a bloc in which economic flows were subordinated to strategic planning. Commercial policy and territorial expansion became intertwined, reinforcing a model in which security concerns justified economic realignment. Access to markets and materials became embedded within geopolitical architecture rather than multilateral cooperation.

By the mid-1930s, global trade had hardened into overlapping economic blocs. Imperial preference tied Britain and its dominions into a preferential network. German clearing agreements structured exchange across parts of Europe and Southeast Europe. Japanese expansion reoriented trade in East Asia. The multilateral trading system that had characterized earlier decades fragmented into selective spheres. Retaliation had evolved into institutional architecture. What began as defensive tariff escalation culminated in a world economy organized around blocs rather than integration.

Trade Contraction and the Collapse of Trust

By the early 1930s, global trade had not merely slowed; it had contracted at a historically unprecedented rate. Between 1929 and 1933, the total value of world trade fell dramatically, reflecting both declining prices and reduced volumes. Commodity exporters experienced especially severe declines as demand evaporated and prices collapsed. Industrial economies, facing shrinking export markets, responded with further defensive measures. The contraction was not simply a mechanical result of falling income. It was amplified by policy choices that reinforced fragmentation and uncertainty.

Currency instability compounded the decline in ways that extended beyond simple exchange fluctuations. As countries abandoned the gold standard at different moments, exchange rates shifted abruptly, creating competitive devaluations and retaliatory adjustments. Some nations devalued their currencies to regain export competitiveness, while others attempted to defend parity longer, deepening domestic deflation and unemployment. Exchange controls and capital restrictions proliferated, limiting the free movement of funds and complicating international settlement. Import licensing systems required bureaucratic approval, adding administrative friction to already strained transactions. These measures were often adopted as emergency stabilization tools, yet collectively they increased opacity and unpredictability in cross-border trade. Merchants faced not only tariff barriers but also volatile exchange rates, uncertain payment mechanisms, and shifting regulatory requirements.

The erosion of trust played a central role in this process. The interwar trading system had relied on expectations of reciprocity and relative openness. When major powers embraced protectionism and discriminatory arrangements, smaller states recalculated their exposure. Confidence that markets would remain accessible diminished. Firms hesitated to invest in export-oriented production if access could be revoked through sudden policy shifts. Governments, uncertain about partner reliability, favored bilateral agreements that provided controlled access over multilateral commitments that appeared fragile.

Institutional cooperation weakened accordingly, as attempts to coordinate recovery proved episodic and ineffective. International economic conferences sought to address currency stabilization and tariff reduction, yet negotiations faltered amid divergent national interests and political pressures. Without credible leadership willing to sustain openness despite domestic hardship, governments prioritized short-term insulation. The gold bloc countries, sterling area participants, and bilateral clearing partners each constructed partial systems of stability, but these arrangements reinforced segmentation rather than restoring universal integration. The absence of enforceable multilateral commitments allowed distrust to harden into policy architecture. What had once been a relatively fluid system of global exchange devolved into regionally bounded and administratively controlled spheres.

Trade contraction in the early 1930s reflected more than cyclical decline or monetary mismanagement. It marked a systemic collapse of confidence in the predictability of international commerce. Tariffs, quotas, exchange controls, and preferential agreements each responded to immediate domestic pressures, yet collectively they dismantled shared expectations of openness and reciprocity. When governments and firms no longer trusted the durability of market access, investment patterns shifted toward self-sufficiency and bloc alignment. The collapse of trade volumes became both symptom and accelerant of fragmentation. Economic nationalism, once justified as temporary defense, crystallized into a restructured global order defined by guarded exchange rather than cooperative integration.

Economic Nationalism and Political Nationalism

Economic fragmentation in the 1930s did not remain confined to trade policy. As tariff walls rose and preferential blocs solidified, economic nationalism increasingly reinforced political nationalism. Governments framed protection not merely as fiscal prudence but as defense of national sovereignty. Control over markets, resources, and currency became symbols of autonomy. In societies already destabilized by unemployment and social unrest, economic self-sufficiency appeared as a promise of restored dignity and order. Commercial policy became entangled with identity and power.

In Germany, the pursuit of autarky under National Socialist leadership fused economic planning with geopolitical ambition in systematic ways. Trade policy was reoriented toward securing raw materials essential for rearmament and industrial expansion, including oil, rubber substitutes, and metals. The Four-Year Plan institutionalized state direction over production priorities, subordinating market signals to strategic objectives. Bilateral clearing agreements were not only financial instruments but political tools that drew neighboring economies into asymmetric dependence, especially in Southeastern Europe. These arrangements ensured access to agricultural goods and raw materials while binding smaller states to German markets. Economic coordination aligned with strategic expansion, reinforcing the regime’s narrative that national revival required insulation from external vulnerability and preparation for conflict. Economic nationalism became both an ideological mobilizer and a logistical foundation for militarization.

Japan followed a comparable trajectory in East Asia, though shaped by different regional constraints and imperial ambitions. Faced with limited domestic access to oil, iron ore, and other essential resources, Japanese leaders increasingly framed economic security as inseparable from territorial expansion. The occupation of Manchuria and subsequent efforts to construct a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” aimed to integrate regional economies under Japanese leadership. Industrial policy, military procurement, and trade controls operated in tandem, reducing reliance on Western suppliers. Commercial restructuring supported strategic autonomy, but it also deepened regional tensions and entrenched bloc logic. Trade flows were increasingly organized around political allegiance and imperial hierarchy rather than open competition, reinforcing the fusion of economic management with geopolitical consolidation.

Even within democratic empires, such as Britain, imperial preference carried political implications. Preferential trade agreements reinforced imperial cohesion at a time when nationalist movements were gaining momentum across colonies and dominions. Economic ties were mobilized to sustain political bonds. The segmentation of trade into imperial and non-imperial channels subtly redefined alliances and rivalries. Economic architecture increasingly paralleled geopolitical alignments.

The convergence of economic and political nationalism also reshaped public discourse across diverse regimes. Protectionism was defended not only as economic relief but as a moral obligation to safeguard domestic labor and preserve national identity. Political leaders portrayed foreign competition as exploitative or destabilizing, reinforcing narratives of external threat. Economic hardship became intertwined with grievances against international systems perceived as unjust or unreliable. In this environment, calls for self-sufficiency resonated beyond fiscal debates and entered cultural and ideological spheres. Sovereignty, dignity, and economic control were invoked as intertwined objectives. As states prioritized internal consolidation and defensive trade policies, compromise appeared as concession rather than cooperation. The language of economic defense hardened into political suspicion, narrowing the space for diplomatic accommodation.

By the late 1930s, economic blocs and political blocs overlapped with increasing clarity. Autarkic ambitions, imperial consolidation, and bilateral dependencies structured both commerce and diplomacy. Fragmented trade systems reduced incentives for cooperation and heightened suspicion among major powers. Economic nationalism did not automatically cause conflict, but it narrowed the space for mutual adjustment. As integration receded, geopolitical rivalry intensified. The hardening of economic boundaries contributed to the broader instability that would culminate in global war.

Structural Lesson: Tariff Escalation Encourages Alignment Without the Initiator

The experience of the 1930s demonstrates a recurring structural principle in international political economy: tariff escalation by a central economic power rarely consolidates its dominance. Instead, it encourages defensive alignment among those affected. When a major market raises barriers, trading partners face a strategic choice. They may attempt accommodation, but they may also diversify markets, deepen regional ties, or institutionalize alternative trade arrangements. Such adjustments can reduce dependence on the initiating power. Protection, rather than preserving leverage, can accelerate realignment beyond the initiator’s control.

Retaliation in this context is not merely emotional or symbolic. It becomes embedded in institutional architecture that outlives the immediate policy dispute. Preferential trade agreements, clearing systems, bilateral quotas, and regional blocs create structured pathways of exchange that gradually substitute for previous dependencies. Once these alternative arrangements mature, reversing fragmentation becomes politically complex and economically costly. Firms invest in new supply chains, establish alternative distribution channels, and reconfigure sourcing strategies to reduce exposure. Governments negotiate reciprocal commitments that deepen interdependence within new blocs. Financial systems adjust to different clearing mechanisms and currency arrangements. As these adaptations solidify, the initiating state may discover that even if tariffs are later reduced, prior centrality has weakened because partners have already recalibrated their structural orientation. The cost of re-integration is higher than the cost of initial divergence.

This dynamic reflects the adaptive nature of trade networks. Economic actors seek predictability and access. When one node becomes uncertain or hostile, others increase coordination to mitigate risk. The resulting alignments are not necessarily anti-initiator in ideology, but they are anti-dependence in structure. In the 1930s, British imperial preference, German bilateralism, and Japanese regional consolidation were not identical projects, yet each reduced reliance on multilateral openness centered on the United States. Tariff escalation at the core contributed to a world in which alignment increasingly bypassed the initiator.

Centrality in trade systems rests not only on size but on openness and reliability. A large economy can exert gravitational pull, yet if it signals unpredictability or sustained exclusion, partners will hedge. Diversification becomes rational self-defense. Such hedging can shift network architecture. The initiator remains large, but less central. Influence becomes conditional rather than assumed. What appears as assertion of sovereignty can function as surrender of connective leverage.

The structural lesson is cautionary and extends beyond the specific conditions of the interwar period. Tariffs may address domestic political pressures or short-term imbalances, but their systemic effects ripple outward through institutional and behavioral adaptation. Escalation among major economies encourages bloc formation, supply chain redesign, and formalized diversification strategies. Once alternative alignments are entrenched, restoring integration requires not only policy reversal but sustained reassurance and rebuilt trust. Businesses must believe that market access will remain stable. Governments must reestablish credibility in multilateral commitments. The history of the 1930s suggests that fragmentation, once institutionalized, becomes self-reinforcing. Alignment without the initiator becomes not a temporary reaction but a durable reconfiguration of economic architecture.

Modern Implications: Partners Hedging Their Bets

The structural dynamics visible in the 1930s remain relevant in the twenty-first century. Major economies continue to occupy central positions in global trade networks, and their policy decisions reverberate beyond domestic borders. When a leading economic actor escalates tariffs or signals sustained retreat from multilateral trade commitments, partners reassess exposure. Supply chains, financial flows, and investment strategies adapt. The scale of contemporary integration differs from the interwar period, yet the logic of hedging remains constant. Economic actors respond to uncertainty by diversifying risk.

In an era of highly interconnected production networks, tariff escalation affects not only finished goods but intermediate inputs embedded within complex, multi-country supply chains. A single manufactured product may incorporate components sourced from several jurisdictions, assembled in another, and marketed globally. When tariffs are imposed at one node, firms confront cascading cost adjustments throughout the chain. Some companies absorb short-term losses; others relocate production, shift sourcing to tariff-exempt countries, or restructure logistics to minimize exposure. Governments, seeking to shield domestic industries from disruption, negotiate regional trade agreements or deepen existing partnerships to secure alternative access. Financial markets respond as well, adjusting capital allocation based on anticipated trade stability. What begins as a targeted tariff can produce systemic recalibration across sectors and regions. These adaptations accumulate, subtly redirecting flows of commerce and investment away from the initiating state. Economic magnitude may persist, but network centrality can erode as firms embed new patterns of exchange into long-term strategy.

Contemporary trade blocs and regional agreements illustrate how alignment can proceed without the initiating power. Multilateral frameworks evolve, new partnerships form, and excluded actors adapt. Once alternative arrangements demonstrate durability, businesses and governments embed them into long-term planning. Reversing fragmentation becomes more difficult than preventing it. Even partial decoupling generates path dependence, as capital, infrastructure, and regulatory harmonization follow new channels. Structural shifts unfold gradually, but their effects endure.

The lesson is neither fatalism nor inevitability. States possess agency in shaping trade architecture. Yet the historical record cautions that escalation can catalyze alignment beyond the initiator’s design. When partners perceive unpredictability or sustained exclusion, they hedge collectively. Centrality rests not solely on size, but on reliability and openness. In contemporary conditions, as in the 1930s, tariff escalation risks encouraging structural adaptation that redistributes influence across the network.

Contemporary Escalation: Donald Trump and the Reacceleration of Tariff Politics

Under President Donald Trump, tariff policy has returned to the center of American economic strategy with unusual force and rhetorical intensity. Framed as a tool to restore domestic manufacturing capacity, reduce persistent trade deficits, and counter what the administration described as unfair trade practices, tariffs have been imposed on steel, aluminum, and a wide spectrum of Chinese imports, later extending to additional sectors. The administration relies on statutory authorities such as Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act and Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 to justify national security and unfair practice claims. These measures are defended not as temporary safeguards but as strategic correctives to decades of liberalization that, in Trump’s view, had hollowed out American industry. Tariff escalation was positioned as an assertion of sovereignty, bargaining leverage, and economic revival rather than retreat. The language surrounding these policies emphasized strength, reciprocity, and national interest. Yet the structural consequences extended beyond bilateral disputes, reshaping expectations among allies and competitors alike.

Trading partners have responded with countermeasures calibrated to exert political and economic pressure. Retaliatory tariffs target American agricultural exports, manufactured goods, and symbolic industries linked to key domestic constituencies. In parallel, affected countries are deepening regional trade agreements and expanding cooperation with alternative partners. Rather than isolating individual adversaries, tariff escalation encourages multilateral conversations among those seeking to reduce exposure to American policy volatility. Even allies recalibrated trade diplomacy to hedge against unpredictability.

Supply chains have adapted incrementally but persistently. Firms have diversified production across Southeast Asia, Mexico, and other jurisdictions to mitigate tariff risk, accelerating trends that were already underway in response to rising labor costs and geopolitical uncertainty. Multinational corporations reassess concentration risk in single-country sourcing models, particularly in sectors such as electronics, automotive components, and consumer goods. Investment decisions incorporate assumptions about long-term trade friction, altering capital allocation and logistical planning. Some reshoring initiatives have occurred, supported by domestic incentives and political messaging, yet broader patterns reflect diversification rather than wholesale repatriation of production. Trade flows have shifted through intermediary countries as firms rerouted exports to avoid direct tariff exposure. The United States retains immense economic scale and technological capacity, but its share of certain trade corridors has declined as alternative manufacturing hubs matured and regional trade agreements facilitate smoother exchange outside direct U.S.–China channels. The structural pattern echoes earlier episodes in which central actors underestimated the adaptive capacity of global networks.

The rhetoric accompanying tariff escalation reinforces the shift in perception among international partners. Trade is increasingly framed as zero-sum competition rather than mutual interdependence, and multilateral institutions are criticized as constraints on American autonomy. Withdrawal from or renegotiation of trade agreements, including the replacement of NAFTA with the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, signal willingness to reorder longstanding commitments through bilateral leverage. Even when negotiations produce revised frameworks, the process communicates conditionality rather than continuity. Allies and competitors alike internalize the possibility that access to the American market could become contingent on shifting political calculations. This perception, independent of specific tariff levels, encourages strategic hedging. Governments pursue new regional agreements, such as expanded Asia-Pacific and European partnerships, partly to secure market access insulated from U.S. policy volatility. In this way, rhetoric and action combine to reshape expectations about reliability.

The reacceleration of tariff politics under Trump illustrates the durability of the structural lesson observed in the 1930s. Escalation may generate short-term bargaining leverage, but it simultaneously incentivizes hedging and alternative alignment. As new trade agreements form and supply chains diversify, centrality becomes more diffuse. The United States remains a major economic actor, yet sustained reliance on tariff instruments risks encouraging structural adaptation that diminishes long-term influence.

Conclusion: When Walls Become Systems

The history of the 1930s demonstrates that tariff walls are rarely temporary instruments. What begins as emergency protection can crystallize into institutional architecture. Smoot–Hawley did not simply raise duties; it altered expectations. Britain’s imperial preference did not merely privilege dominion trade; it reorganized exchange around bloc logic. Retaliation became normalized. Administrative controls hardened. Defensive measures became systems. Once embedded in law, supply chains, and diplomatic alignments, tariff barriers acquire inertia that outlives the crisis that produced them.

Walls in trade are not static obstructions; they generate adaptation. Firms reconfigure sourcing. Governments negotiate alternatives. Financial institutions adjust settlement mechanisms. These adaptations accumulate into parallel structures that reduce dependence on the initiator. When the initiating state later seeks reintegration, it confronts not empty space but an already reorganized network. The wall has become a pathway for others. Fragmentation, once institutionalized, reshapes centrality.

The central lesson across the interwar period and the contemporary moment is structural rather than partisan. Economic magnitude alone does not guarantee leadership. Centrality depends on openness, predictability, and the willingness of partners to align voluntarily. When a major power substitutes tariff escalation for cooperative engagement, it risks encouraging the very diversification that diminishes its leverage. Alignment without the initiator is not an act of hostility; it is a rational response to uncertainty.

When walls become systems, they redefine the architecture of exchange. Reversing them requires more than lowering duties; it requires rebuilding trust. The experience of the 1930s illustrates how quickly fragmentation can harden into durable blocs. The contemporary era presents a similar test. The choice is not between sovereignty and interdependence, but between structural centrality and gradual displacement. History suggests that the durability of influence rests less on the height of walls than on the stability of the bridges they replace.

Bibliography

- Cain, P. J., and A. G. Hopkins. British Imperialism, 1688–2000. 2nd ed. London: Longman, 2002.

- Cartwright, Madison. “Embedded Hegemony and the Evolution of the United States’ Structural Power.” International Relations (2024).

- Drummond, Ian M. Imperial Economic Policy, 1917–1939: Studies in Expansion and Protection. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1974.

- Eichengreen, Barry. Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Ignatenko, Anna, Ahmad Lashkaripour, Luca Macedoni, and Ina Simonovska. “Making America Great Again? The Economic Impacts of Liberation Day Tariffs.” Journal of International Economics 157 (2025).

- Irwin, Douglas A. Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

- —-. Peddling Protectionism: Smoot–Hawley and the Great Depression. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Kindleberger, Charles P. The World in Depression, 1929–1939. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

- League of Nations. World Economic Survey, 1932–1933. Geneva: League of Nations, 1933.

- Martín, Álvaro. “A Pandemic of Protectionism: How Economic Isolationism Affects the Economy.” Journal of New Finance 2:1,1 (2021).

- Mazower, Mark. Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century. New York: Vintage, 1998.

- Overy, Richard. The Inter-War Crisis, 1919–1939. 2nd ed. London: Longman, 1994.

- Pryke, Sam. “Economic Nationalism: Theory, History and Prospects.” Global Policy 3:3 (2012), 281-291.

- Rodrik, Dani. Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017.

- Temin, Peter. Lessons from the Great Depression. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989.

- Tooze, Adam. The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. New York: Viking, 2006.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.16.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.