Slavery, long banned and universally condemned, persists in many corners of the world, victimizing tens of millions of people.

By Eleanor Albert

PhD Student in Political Science

The George Washington University

What Is Modern Slavery?

Half of all victims of modern slavery are in debt bondage. Women and girls make up 71 percent of all victims. 1 in 4 victims of modern slavery is a child.

Slavery dates back to ancient times and has left its trace across cultures and continents. Though slavery is now universally prohibited, with protections for individual rights enshrined in national and international laws, it persists.

Slavery exists any time a person has been recruited, transported, or compelled to work by “force, fraud, or coercion,” according to the U.S. State Department. Victims do not have the means to leave of their own will. Slavery today most often occurs in industries that are labor intensive, low skilled, and underregulated.

Slavery occurs in the gulags of North Korea, on the battlefields of Iraq and Syria, and in the brothels of Eastern Europe. Its victims are children forced into military action in the Democratic Republic of Congo or born into debt bondage at brick kilns in India, young men laboring on rickety fishing boats in Thailand, and children and women pressed into domestic servitude in Haiti.

Slavery is most prevalent in impoverished countries and those with vulnerable minority communities, though it also exists in developed countries. Tens of thousands toil in slave-like conditions in industries such as mining, farming, and factories, producing goods for domestic consumption or export to more prosperous nations. Profiteers prey on vulnerable people and operate with relative impunity. Slavery today usually takes one of the following forms: bonded labor, domestic servitude, sexual exploitation, or forced marriage.

Case Study: India

Bonded Labor

DEFINITION: when a person offers labor in exchange for a loan or to pay off debt inherited from a relative.

Bonded labor, also known as debt bondage or peonage, often resembles a standard labor contract, but the laborer is rarely able to repay the principal and interest. Debt bondage is one of the most common forms of contemporary slavery worldwide.

Bonded labor is among the leading forms of slavery in India and across South Asia. Though India is the seventh-largest economy in the world, it accounts for around one-third of the world’s poor [PDF], with more than 224 million people living on less than $1.90 a day. Amid such extensive poverty, slave labor is rife.

India abolished its caste and bonded labor systems decades ago, but social stratification remains pervasive. Families remain enslaved for generations, working in dangerous conditions without the means to pay for their freedom. India’s bonded labor system disproportionately ensnares Dalits, the bottom class of the Hindu caste system, as well as tribal communities and religious minorities. The cycle often begins with a loan request made to a landlord or business owner for expenses incurred burying a family member, treating an illness, procuring employment, or staging a wedding. The loan provider can then strongarm laborers or threaten to take away their family’s shelter to extract more work than the value of the original loan. This can result in a family accruing debt over generations. Brick kilns, rice mills, farms, and embroidery factories are notorious hubs of debt-extorted labor.

Bonded labor can coincide with another form of contemporary slavery, domestic servitude, in which someone is forced to carry out daily chores in private households.

Domestic Servitude

DEFINITION: when an individual performs domestic work without the ability to leave.

This often takes place within private homes, where it is hidden from authorities and potential whistleblowers. It entails psychological control and physical abuse. Women and children, often migrants, are the most common victims. With few opportunities for legal recourse, they often refrain from reporting their work conditions.

Women and children are not only the primary victims of domestic servitude, but also of sexual exploitation, which accounted for nearly 20 percent of the world’s victims of forced labor [PDF] in 2016, according to the International Labor Organization and Walk Free Foundation.

Sexual Exploitation

DEFINITION: when women, men, or children are forced to perform nonconsensual commercial sex acts.

Victims of sex trafficking are often lured by the promise of employment. Sexual exploitation can also occur as a form of debt bondage, with traffickers claiming that individuals must work to pay for their transportation, recruitment, upkeep, or even sale.

Children, particularly girls, are often enslaved another way, through forced marriage. Girls as young as nine can be forced into arranged unions, often the result of financial transactions or cultural practices. Children under the age of fifteen account for 44 percent of child victims of forced marriage.

Forced Marriage

DEFINITION: a union to which one or both parties did not consent and that cannot be left freely.

Such arrangements can involve forced labor, sexual exploitation, or domestic servitude. Young girls account for many of the victims of forced marriages. About 88 percent of the victims [PDF] are women and girls; children make up more than one-third of all victims.

North Korea: Case Study

North Korea has carried out or enabled multiple forms of slavery. Its extensive state-sanctioned forced labor system interns tens of thousands of people in camps, while others are shipped abroad to work under close guard, unable to leave and paid little, if anything. Criminal networks and individuals profit off the black market, including through human trafficking. In North Korea, women are sold into marriage for prices ranging from $150 to $1,500, and defectors to neighboring China are often sexually exploited amid growing demand for brides.

North Korea sentences citizens accused of anti-state infractions to time in prison or labor camps. An estimated 80,000 to 120,000 prisoners work in mines, factories, farms, and logging camps, the United Nations found in 2014. Further, Pyongyang exports labor; more than fifty thousand North Koreans forcibly work in the logging, mining, textile, and construction industries in China and Russia. Other countries in Africa, Asia, and Europe have reportedly used North Korean labor in similar industries as well. Laborers work long hours in unsafe conditions and with inadequate rations while the regime earns between $1.2 billion and $2.3 billion annually for their labor, according to the International Network for the Human Rights of North Korean Overseas Labor.

Women and girls looking to leave North Korea are vulnerable to trafficking, forced marriages or concubinage, and being sold into prostitution. Though some are kidnapped, drugged, or detained, many enter the web of traffickers seeking out the promise of a better life and a good job, only to be sold multiple times before being forcibly married. Most of the twenty to thirty thousand children of North Korean women living in China are believed to come from such marriages. Other North Korean women are forced into sexual slavery in brothels or via online networks, or as hostesses in nightclubs and karaoke bars.

What Drives the Slave Trade?

“I was looking for a job.”

This is often how a slavery survivor’s story begins. A confluence of factors can leave countries and communities at risk.

Absence of the Rule of Law – Democratic Republic of Congo Case Study

Slavery thrives in the absence of a properly functioning law enforcement system. It is often abetted by police and other authorities. Without adequate enforcement of existing laws and the strengthening of legal frameworks, human traffickers operate with impunity.

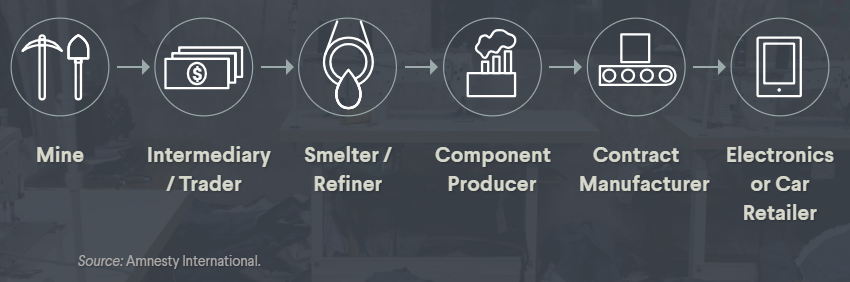

The fractured government of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) has left large groups of people vulnerable to slavery. Decades of ethnic and political turmoil have been compounded by weak governance structures and large displaced populations. There are more than 473,000 refugees and 3.9 million internally displaced people in the DRC. The huge central African nation has also faced an influx of migrants, predominantly from its eastern neighbors. Eastern Congo is dominated by dozens of domestic and foreign-backed militias, which wield power over much of the country’s lucrative natural resources. The DRC is the world’s largest producer of cobalt and also has vast reserves of gold, diamonds, coltan, tin, tantalum, and tungsten. Many of these minerals are critical components of laptops, smart phones, and other consumer electronics. These natural resources have created a profit motive for traffickers and militias to exploit vulnerable communities. Large consumer demand for cheap electronics drives illicit mining activities, experts say.

Insurgent groups in the eastern provinces of North and South Kivu, Ituri, Maniema, and Tanganyika occupy territory with fertile land and illegal artisanal mines. By some estimates, there are between five hundred thousand and two million artisanal miners in eastern Congo. Overall, extractive industries, such as mining, account for 22 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Refugees and Congolese have been forced to work the mines.

Amid civil war, women and children have been the victims of sexual slavery, rape has been used as a weapon, and boys have been forced to serve as soldiers in armed groups. The DRC’s protracted conflicts and limited resources have made combating slavery all the more difficult. Corruption and patronage networks run deep, and politicians and the military have links to armed groups.

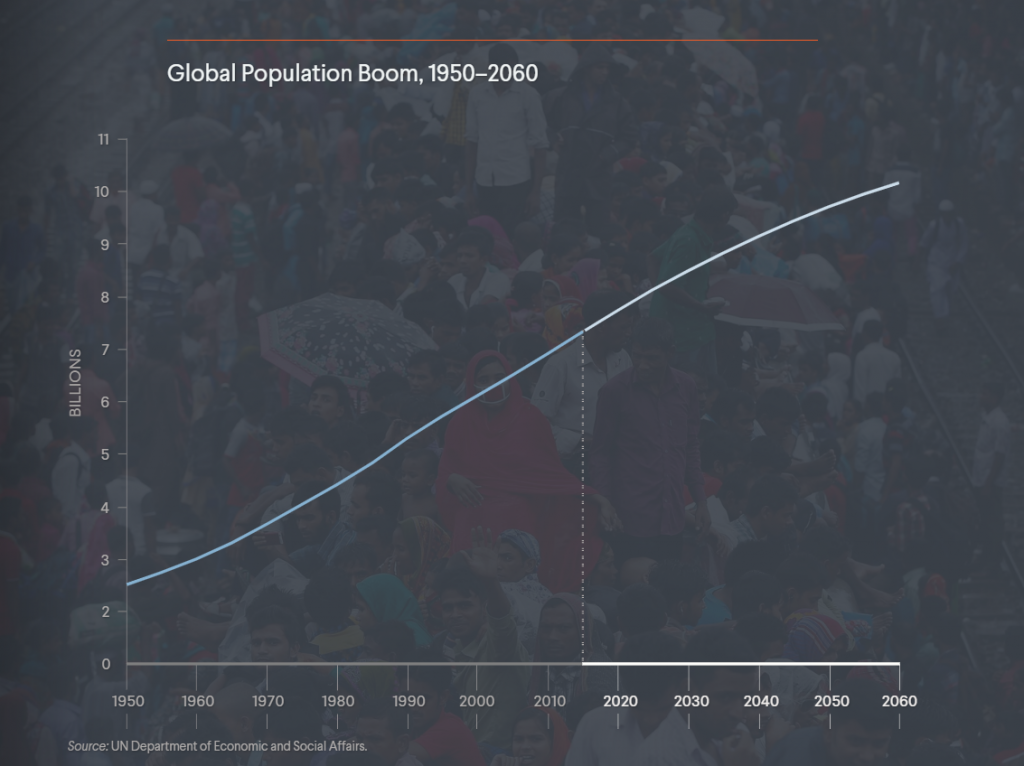

A Population Boom

The world’s population rose from 2.5 billion in 1950 to nearly 7.4 billion in 2015. The world is also in a state of historic flux: a record-setting 65.6 million people were displaced at the end of 2016 by war and persecution, and still more by economic uncertainty and environmental destruction. China and India, the two most populous nations, have lifted millions out of poverty, yet millions more in both countries remain marginalized and are susceptible to abuse. In dire straits, displaced people seek out perilous employment and are vulnerable to false offers. Traffickers prey upon the multitude of displaced people.

Poverty

About 765 million people worldwide live in extreme poverty, making less than $1.90 per day. Those in destitute conditions have limited means to support their families. In the absence of alternatives, many people, taking risks, are lured by sham offers of better futures.

Marginalized Groups – Thailand Case Study

Groups that face discrimination, including ethnic and religious minorities, women and children, and migrants and refugees, are vulnerable to enslavement. At particular risk are those fleeing war and armed conflict, such as the Yazidi minority in Iraq and Syria, and Myanmar’s Muslim Rohingya population.

The fishing industry in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand, has been notorious for severe labor abuses. With eleven of the world’s largest fisheries [PDF] in Asia, labor is in heavy demand. These megafisheries often employ migrants from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

The majority of Thailand’s fish harvest (mostly shrimp and tuna) is exported to Asian, European, and American markets. The industry, which brings in more than $7.3 billion [PDF] annually, suffers from a labor shortage. Fishing, processing, and packaging firms have come to rely on migrant labor provided by illicit networks, whose recruiters often falsely promise high-paying jobs in regulated industries. Migrants, who account for 5 to 10 percent of the Thai workforce, sometimes must work years to pay back illegal recruitment fees.

Those employed in the Thai fishing industry are often subject to exploitation and abuse [PDF], including unclear contracts, withheld wages, and dangerous working conditions. Escapees have reported threats of violence, beatings, and sexual abuse, as well as the execution of their shipmates.

Collusion between police and traffickers has impeded efforts to address forced labor in the Thai fishing industry. Despite crackdowns by federal authorities, police and provincial administrations have been accused of accepting bribes from labor smugglers.

War and Conflict – Iraq and Syria Case Study

Instability brought on by war or conflict can expose besieged communities to forced labor networks.

The rise of the self-proclaimed Islamic State and violence in Iraq and Syria have left residents of many communities at risk of capture or enslavement. When Islamic State forces overran towns populated by the Yazidi ethnoreligious minority in northern Iraq in 2014, they captured thousands of Yazidis and displaced an estimated 360,000 [PDF]. Hundreds of thousandsfled, while thousands were kidnapped or killed by militants. During their occupation of these areas, which ended in 2017, militants instituted slavery involving the sexual exploitation of women and girls. (They have done the same to Christians and other minorities.) Some Yazidis were promised jobs, while others were kidnapped or captured as territory fell to the Islamic State. As the militants were ousted from occupied territories, additional horror stories of the enslavement of Yazidi women and girls emerged.

Yazidi women and girls as young as eight were forced into sexual slavery, sold in markets or gifted by commanders to fighters as brides. Some were sold at prices [PDF] between $200 and $1,500. Captives were also forced into domestic servitude, cooking, cleaning, and, at times, raising children. Islamic State extremists enslaved 6,417 Yazidis, according to the Kurdistan Regional Government. An estimated three thousand Yazidisremained captive as of September 2017, according to the United Nations.

While many Yazidi men have been executed, young boys have been forced [PDF] to convert to Islam and placed in indoctrination and military training camps. The United Nations described the recruitment and use of children in combat in Syria by the Islamic State, as well as by other parties to the conflict, as “commonplace.” Those who refused or attempted to escape suffered beatings, torture, rape, or execution.

Natural Disasters – Haiti Case Study

Weather patterns are increasingly unpredictable, and climate catastrophes, such as monsoons and earthquakes, have become more common. Extreme weather, as well as resulting pandemics, can ravage a country’s physical infrastructure, displace communities, and increase the desperation of already marginalized groups.

Among those most at risk are the restavek, children whose parents cannot support them and who are sent from rural areas to live in the homes of relatives or other families in cities. The Haitian Creole word, derived from French, means “to stay with,” and the process has become embedded in Haitian culture. These children often find themselves trapped in domestic servitude.

About 286,000 children, mostly girls under the age of fourteen, work as domestic servants, according to a 2015 report. These children are made responsible for household chores—cleaning, cooking, washing clothes, fetching water—and are often subject to physical abuse and malnutrition. As adults, former restaveks lack education, skills, and aspirations, leaving them once again vulnerable to trafficking. Some resort to begging, prostitution, or crime to support themselves.

A Trafficker’s Motives

Greed drives the modern slave trade. “This is an economic crime,” said Kevin Bales, a leading expert on contemporary slavery, in a TED Talk. “People do not enslave people to be mean to them; they do it to make a profit.”

Slavery generates $150 billion for traffickers annually.

United States and Europe – Case Study

Commercial sexual exploitation is one of the dominant forms of contemporary slavery in Europe and the United States. Its victims, mostly women and girls, are usually lured with the promise of a job, often in modeling, acting, or dancing, but are then forced to prostitute themselves or perform sex acts facilitated by escort services, massage parlors, brothels, or online listings. Homeless, runaway, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) youth and migrants are disproportionately targeted. Inadequate resources for prosecutions, training, and victim support programs, as well as lax enforcement of antitrafficking laws, impede efforts to eliminate commercial sexual exploitation in Europe and the United States. Because prostitution is largely criminalized, the prospect of incarceration and subsequent criminal records deters victims from seeking help from authorities.

In the United States, sex trafficking accounted for 73 percent of the 7,572 human trafficking cases reported to the national hotline in 2016; far more cases go unreported, experts say. Nearly half of these victims were girls between the ages of twelve and seventeen. Forty percent of all human trafficking cases reported in the United States occur in just five states: California, Texas, Florida, Ohio, and New York.

More than 65 percent [PDF] of trafficking victims in Europe and Central Asia were the victims of sexual exploitation, according to a 2014 UN report. Trafficking is especially prevalent in Eastern and Central Europe, Southern Europe, and the Balkans; as major entry points to the European Union, they have been exploited by transnational criminal networks. Among the European countries where women are most at risk of being trapped in sexual slavery are Moldova and Romania. Moldova is the poorest country in Europe, with a GDP per capita of $1,935. Romania has the highest poverty rates in the European Union, and the World Bank says that nearly 40 percent of Romanians are vulnerable to “poverty and social exclusion.” Analysts say that poverty, corruption, gender inequality in society, and domestic violence drive women to take risks to change their fates; traffickers exploit their economic desperation and vulnerability.

Modern Abolition

Dedicated abolitionists spearheaded the campaign to end the triangular slave trade between Western European powers, their colonies in the Caribbean and the Americas, and West African territories in the nineteenth century. Present-day circumstances require collaboration among a wider array of actors, including governments, international organizations, international lawyers, local nongovernmental organizations, and multinational corporations. The persistence of human rights abuses, say modern abolitionists, corrode societies and the rule of law. Slavery is also a drag on economic growth in developing countries. The following strategies, experts say, can help fight slavery.

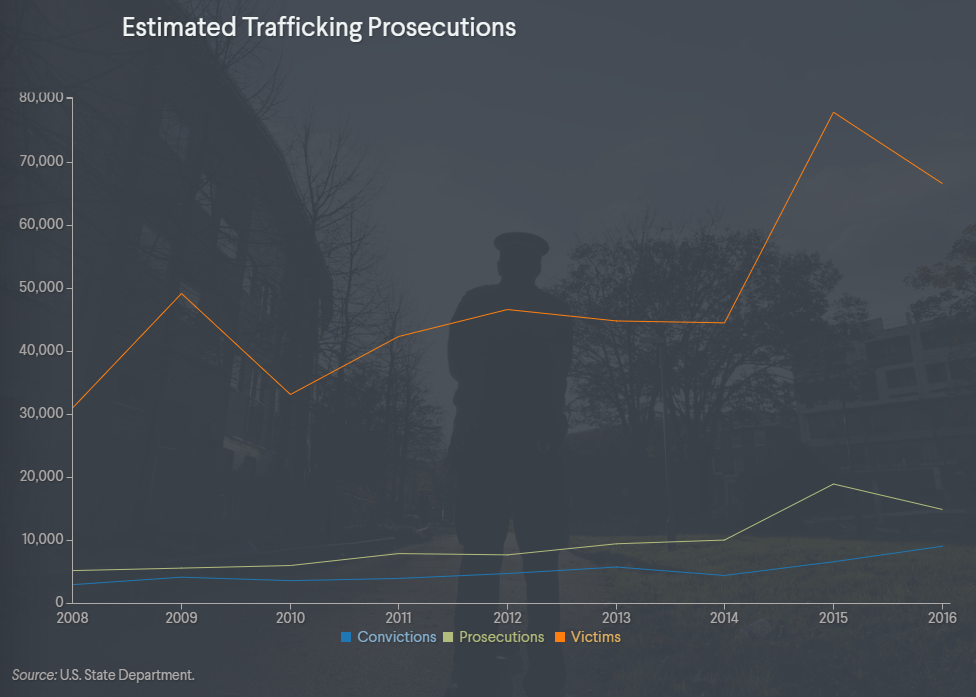

Toughen Law Enforcement

While most countries have laws to protect citizens from traffickers, analysts point out that enforcement is often weak. Prosecutions of perpetrators are few, and convictions even fewer. Activists say that governments can improve enforcement by streamlining court processes and training law enforcement and judicial officers, emergency room nurses, labor monitors, and family services providers—those most likely to observe conditions of slavery. However, underground networks often evade prosecution, and middlemen, even if imprisoned, are easily replaced.

Some experts suggest alternative legal routes, such as strategic litigation [PDF]. Civil suits brought by human rights litigators, private law firms, and rights organizations seek damages to compensate survivors and punish the perpetrators of slave labor and those who indirectly profit from it. These cases could, in turn, incentivize governments and businesses to end labor abuses.

Activists say that legal efforts to eradicate slavery have been too piecemeal. Governments, they say, should pass and enforce legislation that criminalizes slavery in all forms. Experts say that steady prosecution deters would-be traffickers and brokers by making it more costly to buy and sell people and their labor. Profit margins decline, and the prospect of steep fines or jail time looms. “Failing to reverse the risk-reward equation for all enablers within the network of human trafficking will leave us struggling to slow this growing illicit industry,” writes Annick Febrey of Human Rights First, a U.S.-based human rights organization.

Build Transparent Supply Chains

Governments alone cannot end slavery. “The focus on the nation-state as the hub of response on combating slavery needs to shift and expand,” says E. Benjamin Skinner, founder of the New York–based nonprofit investigative organization Transparentem. Experts say that businesses, including multinational clothing companies, global seafood exporters, and electronics makers, have an ethical responsibility to eliminate forced labor. It is also in their best interests, because any connection to slavery within their supply chains “pollutes and taints their work,” says Mark P. Lagon, chief policy officer of the Washington-based Friends of the Global Fight Against AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Some countries and U.S. states have enacted transparency legislation, requiring businesses to make public assessments of their supply chains in a bid to prevent forced labor, child labor, and human trafficking. California’s Transparency in Supply Chains Act [PDF], passed in 2010, requires public reporting from firms that generate at least $100 million a year globally, and the United Kingdom enacted the Modern Slavery Act in 2015, requiring the same of businesses with annual revenues of more than £36 million (about $47 million). But even local and national transparency laws that require disclosures do not mandate that companies investigate their supply chains. There is evidence, however, that businesses with complex international supply chains, including Walmart, Mars, Nestle, and Target, have launched pilot projects with their suppliers to eliminate forced labor and improve working conditions. Organizations including the Walk Free Foundation, KnowTheChain, and the International Trade Union Confederation provide guidance and reporting to help businesses study their supply chains. Experts say corporations should move beyond pilot programs and make ethical sourcing and labor recruitment a central part of their business practices.

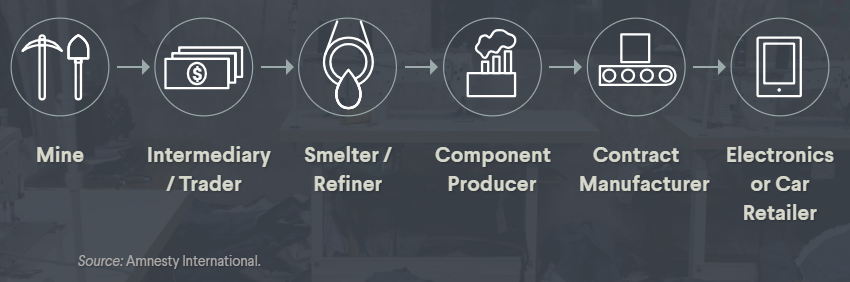

Cobalt is a critical component of rechargeable batteries for electronic consumer products and for automobiles that are exported to markets all over the world. The mineral is often extracted from artisanal mines in the DRC before being traded and then sent abroad, often to China, for refinement. The processed cobalt then heads to Asian component producers and electronic manufacturers for assembly before the final products are sold in the United States, Europe, and across Asia.

Name and Shame

Leading watchdog countries condemn incidents of slavery and impose consequences on countries that fail to take decisive action. For example, a Tier 3 ranking on the U.S. State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons Report triggers restrictions on development aid and other assistance. The State Department report and the European Union’s equivalent assessments provide insight into national efforts to combat human trafficking. Such reports also track changing policies on modern-day slavery.

Studies indicate that being called out in such reports—along with the accompanying threat of sanctions or other economic consequences—incentivizes governments to criminalize slavery. The State Department estimates that worldwide, governments passed twenty-five pieces of legislation on human trafficking in 2016. Still, diplomatic pressure alone is not often sufficient to get countries to better enforce antislavery laws.

Spread the Word

Prevention starts with public revelations, such as reports on the horrors of enslavement under the Islamic State, or the testimonies of defectors from North Korea’s labor camps, and those who have fled fishing vessels off of Thailand. Partnerships between community-based programs and international organizations can inform vulnerable people of their rights, expose methods employed by traffickers, and provide training that leads to alternative employment. This programming can help communities avoid falling prey to recruiters. Rehabilitationand prevention programs in the most at-risk countries tend to receive limited funding, but they can help survivors stay out of slavery and minimize their chances of being trafficked anew.

Investigative journalists and human rights researchers also play an important role, exposing abuses and identifying slave labor in the global supply chains of products distributed worldwide. Examples include the Associated Press’s 2016 investigation into the fishing industry in Southeast Asia, CNN’s ongoing Freedom Project, which publishes harrowing first-person stories, and the Guardian’s partnership with Humanity United.

Originally published by the Council on Foreign Relations under the terms a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.