Indigenous people in Ecuador’s Amazonian region (the Oriente) lived outside of modern markets and political systems until around 40 years ago.

Dr. Robert F. Wasserstrom

Social Anthropologist

The Terra Group

Dr. Teodoro Bustamante

Research Professor

FLACSO Ecuador

Abstract

According to most recent research, Indians in Ecuador’s Amazonian region (the Oriente) lived outside of modern markets and political systems until around 40 years ago. But this view obscures the essential role of indigenous labor in earlier cycles of extractivism and exploitation. Beginning in the 18th century, lowland Quichua and other ethnic groups were defined as much by their place within long-distance economic networks as they were by their languages or cultures. Using newly discovered historical records and other sources, we can now reconstruct the ebb and flow of commodity booms in Amazonian Ecuador and their impact on indigenous populations.

The Indian serves the white man because he believes that he has no other choice…the day that he knows for sure that he is free, he will never serve them again, and they will be forced to work with their own hands or leave their homes.

Anonymous rubber collector on the Curaray River, ca. 1905 (Porras, 1973)

Introduction: Among the Saints, Savages and Headhunters

In 1847, Gaetano Osculati, an Italian adventurer, walked from Quito across the Andes, then headed south to the Napo River, and finally paddled by canoe to Brazil (Map 1). Upon his return to Italy, he published a widely read account of his travels (2003 [1854]). Other narratives soon followed: by Manuel Villavicencio (1858) ; Manuel Almagro (1866) ; James Orton (1871) ; Alfred Simson (1886); Marcos Jiménez de la Espada (1998 [1927-1928]) , to name a handful of authors. Almost invariably, they lamented the region’s lack of commerce and modern agriculture, the strangeness of its native people, the incredible riches going to waste, the backwardness of its ruling class. “This portion of the tropics abounds in natural resources which only need the stimulus of capital to draw them forth,” wrote the Rev. J. C. Fletcher in his introduction to Orton’s book (1871: xvii).

Similar tropes survive today: the Amazon’s marginality, its abandonment by distant governments, the isolation of its indigenous people ( Perreault, 2002: p. 31 ; Sawyer, 2004: p. 40 ; Yashar, 2005: p. 111 ; López & Sierra, 2011 ). “[D]espite 400 years of Spanish incursions and several decades of republican administration under the Ecuadorian government,” writes Perreault (2002: p. 31) , “inhabitants of the Upper Napo remained relatively isolated from the rest of Ecuador―physically and socially―due to scanty communication networks and administrative negligence.” According to this common view, fundamental change began only in the 1960s and 1970s, when government-sponsored land reform, oil extraction and colonization brought about “rapid integration with market forces” and “a disruption of indigenous lifeways” ( Perreault, 2003a: p. 74 ; Perreault, 2003b: p. 104 ; see also Hutchins, 2007: p. 79 ). Yet such tropes seriously distort our view of the region and its inhabitants. They ignore the push and pull of external forces along Ecuador’s Amazonian frontier over the past 150 years. As a result, recent ethnography often fails to explain fully how native identities emerged, what they signify and how they are changing today.

Nineteenth century travelers provided a more nuanced view of Amazonia. They were not simply adventure tourists, plant collectors or gentlemen dilettantes (who came later, in the 1920s). Instead, they frequently told us a great deal about the far-flung trading networks linking native people in the Upper Marañón Valley with Quito and southern Colombia. Such networks became a major organizing principle of indigenous life, because they largely shaped the social, economic and cultural roles available to Amazonian Indians. As they expanded or contracted over the years, native populations, territories and identities merged or differentiated along with them. Zápara, Quichua, Shuar and Achuar, Cofán, Siona and others were defined as much by their place within these networks as they were by their native languages or cultural practices. According to Hill (1999: p. 704) , “there were, and still are, pockets of remotely situated territory where indigenous peoples lived in relative isolation from the independent nation-states in the nineteenth century. However… [they] had all adapted, either directly or through the mediation of other indigenous peoples, to long processes of conquest, missionization, and other forms of colonial domination prior to the rise of independent nation-states.” With the help of newly discovered archival records, it is now possible to reconstruct at least in part these historical processes and evaluate their impact on indigenous populations into the present century.

Most recent anthropological studies in Ecuador’s Oriente have focused on cosmology, worldview and other cultural issues (for examples, see Uzendoski, 2005; Kohn, 2013 ). Here we problematize a different question: the constant reshaping of ethnic boundaries and indigenous populations from Independence in 1822 to the present day. Specifically, we examine long-term economic and demographic changes within what Ferguson and Whitehead (1992: p. xii) call the “tribal zone,” a geographic and conceptual region “continuously affected by the proximity of a state, but not under state administration.” Within this zone, they write (1992: p. 3), “the wider consequence of the presence of the state is the radical transformation of extant sociopolitical formations, often resulting in “tribalization,” the genesis of new tribes.” Ethnic identities “are in reality entirely new constructions, shifting constellations of compound identities and interests that, in their politically potent actuality, never existed before.” The state itself takes multiple and diverse forms, often represented by “proxies” whose identities shift over time: landowners, government officials, rubber collectors, missionaries―outposts of ruling elites who also compete to exercise governance (see Krupa, 2010: pp. 319-320) . These concepts provide a critical starting point in analyzing present-day indigenous populations in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Prelude: Ethnic Networks and Trade, 1750-1885

Modern commercial networks in the Oriente trace their origins to Jesuit missionaries who extended their reach along the Napo and adjacent rivers during the 17th and 18th Centuries. Between 1660 and 1750, the Jesuits organized 74 reducciones (settlements) as far east as the Río Negro in Brazil and as far west as Archidona in the Andean foothills (Taylor, 1999: p. 223) . They imposed “a syncretic native culture transmitted by [mission] Quichua,” as well as shared forms of social organization and religious practice ( Taylor, 1999: p. 227 ; see also Reeve, 1994 ).1 Disease and forced labor took a horrific toll: within mission territory, native population dropped from around 200,000 in 1550 to 20,000 or 30,000 in 1730 ( Taylor, 1999: p. 225 ; Newson, 1995: p. 81 ). Trade with outsiders was prohibited in theory and difficult in practice. At least the missions offered a degree of protection from Portuguese slave raids and provided sporadic access to metal tools (Golub, 1982 ). As Taylor (1994: p. 18 ) has pointed out, “Many of the traits that are [today] attributed to their primitiveness―small social and domestic groups, egalitarianism, simple technology―in fact represent an adaptation to the colonial world.” In 1767, the Jesuits were expelled from Spain and its colonies. For the next 80 years, native groups were left largely on their own.

Following independence in 1822 and ensuing civil war, Jesuit-dominated commerce in eastern Ecuador was replaced by civil authorities and a few well-connected merchants ( Villavicencio, 1858: p. 392 ). Three major routes crossed the Andes: the main one that Osculati followed, along with two other little-used tracks farther south (Map 2). Most travelers followed the trail from Quito to Baeza, where it split into two branches. Around Archidona, Quichua-speaking Indians (known as “Quijos”) panned for gold in surrounding rivers, as they had in Jesuit times; along the eastern route, they grew agave (for pita fiber) and tobacco ( Osculati, 2003: p. 153 ). These people were isolated, but not free. Passing through Quijos territory in 1857, Jameson (1858: p. 346) was shocked at the rapacity of repartos imposed by local officials.2 “Quito nearly monopolizes the trade,” noted another traveler, James Orton (1871: pp. 194-196) . “It is hard to find an Indian whose gold or labor is not claimed by the blancos.” In 1882, the French diplomat Charles Wiener (2011 [1882]: p. 196) called them “prisoners without uniforms.”

As Osculati quickly learned, the Quijos trails formed only a single node within much broader commercial networks. From Ahuano, four separate tracks led southward through Zápara settlements to the Pastaza River.3 Beyond the Pastaza, Zápara war parties raided Shuar and Achuar groups (then called “Jívaro”), who also supplied blowguns, curare, barbasco (fish poison), ornaments and sometimes a little gold.4 In effect, the Jívaro occupied one end of an economic network that defined three distinct ethnic roles: “tame” Christian Indians (Quijos), who lived north of the Napo and worked directly for white merchants; “peaceful but uncivilized” Zápara intermediaries (Orton’s words) living on the frontier who traded in Jívaro territory; and infieles (heathens) or indios bravos, who brought curare, slaves and other things from people living farther down the Marañón Basin.

After mid-century, “peaceful but uncivilized” Zápara began to disappear. This transformation occurred in several stages. Around 1850, Shuar families on the Pastaza River moved north into Zápara territory, where they hoped to “extricate themselves from the continuous persecutions of interior [Jívaro] tribes” ( Villavicencio, 1858: p. 50 ). They settled near San José de Canelos, where white merchants sold tools, cloth, needles, beads, thread and fishhooks brought from Riobamba. Within a few years, 165 households―often speaking Shuar, Zápara and Quichua―lived in the Canelos settlements ( Almagro, 1866: pp. 122-125 ). Meanwhile, semi-independent Zápara groups survived only along the margins of Canelos territory, particularly along the lower Curaray River where they were continually harassed by infieles ( Orton, 1871: p. 220 ).5 As early as 1845, Fr. Manuel Castrucci (1849: pp. 12-14) estimated the entire Zápara population at 1,000 people, whereas two centuries earlier, it included at least 35,000 ( Newson, 1995: p. 114 ). By 1887, the Dominican pioneer François Pierre (1983) declared that everything west of the Villano River was occupied by Quichua-speaking Canelos Indians―mostly former Zápara, Shuar and Achuar families who had shifted their ethnic affiliation.

In the early 1860s, international quinine prices rose and a Colombian company sent 1,000 collectors into Ecuador’s eastern forests ( Esvertit, 2008: p. 121 ). By 1875, however, quinine production had shifted to Asia and economic activity in the Oriente largely collapsed. Meanwhile, the Jesuits returned and forced white merchants to leave San José de Canelos, the area’s major commercial center ( Simson, 1886: p. 56 ; Wiener, 2011 [1882]: p. 195 ).6 When the English traveler Alfred Simson arrived at Canelos that year, he found its inhabitants eager to trade for his fishhooks, needles and beads, but with little to give him in return (Simson, 1886: p. 100) . He attributed this to laziness; more likely, it reflected the enforced isolation of Jesuit rule and a generalized collapse of commerce. Simson himself (1886: p. 102) noted that Indian men occasionally walked ten days over a nearly impassable mountain trail to Riobamba, where they bought steel spearheads, although he failed to understand why they would do so.

Nonetheless, his account remains useful for us because it provides an important picture of events along Ecuador’s eastern margins just before the Rubber Boom. On the Upper Napo, Simson took refuge with Antonio Llori, a merchant who lived in Ahuano with “a couple of traders [called Quintero] and their wives, with the mother-in-law of one of them (a Záparo woman)…” (Simson, 1886: p. 238). This woman had become an important trader in her own right, especially among her Supuni Zápara kinsmen on the middle Curaray (Simson, 1886: p. 177) . Not long before, he wrote, the Supini had attacked another Zápara group, the Nushinus, “killing many of the men and robbing the women, children and their chattels, the second either for use as servants or for sale.” Children were sold for “a hatchet, a knife, a couple of yards of coarse lienzo [cloth], and a few fish-hooks, needles and thread, or any special article they may most stand in need of…” Evidently, Jesuit-induced scarcity had revived older patterns of warfare among Zápara groups in the tribal zone.7

Ethnic Realignment and the Rubber Boom, 1885-1930

Within ten years of Simson’s travels, the Ecuadorian frontier underwent profound economic and social transformation. During the 1870s, rubber harvesting extended from the lower Marañón into the Napo Basin.8 At first, only four white merchants traded for rubber there. But between 1880 and 1890, rubber collection grew from a dozen small posts to 35 large ones (Gamarra, 1996: p. 47) . Most of the remaining Zápara families along the Upper Curaray were soon absorbed into these new enterprises. As caucho collection spread, Quijos and Canelos people were also swept into “the vortex” and dispersed throughout western Amazonia.9 Blocked by Peruvians from further expansion toward the Marañón after 1895, many Ecuadorian caucheros shifted their operations to the Napo and Aguarico Rivers (Bravo, 1907: p. 63; Bravo, 1920: p. 90; Alomía, 1936: pp. 307-308) . There they became known as señores ribereños, “lords of the river banks.” By 1900, 72 fundos (estates) were recorded along the lower Napo―double the number of the 1880s (Gamarra, 1996: p. 47) . In 1905, according to Fuentes (1908) , señores ribereños on the Napo sent nearly 35,000 kg of rubber to Iquitos and brought back supplies worth 150,000 soles ($75,000, worth roughly $1.5 million today).10

Indigenous people on the lower Curaray bore the early impact of rubber collection.11 They included Zápara and Canelos people from Villano and Bobonaza, along with highland Indians, Cofán, Siona and Quichua- speaking people (who usually called themselves runa) recruited from the Upper Napo or fleeing from other caucheros. (Trujillo, 2001: pp. 204-207 ; Porras, 1973 [1905] ; Cabodevilla, 1994: p. 142 ). As rubber collection expanded, indigenous work gangs penetrated further into the forest, where they often fought surviving bands of indios bravos. The consequences for unconquered bands were inevitable: “death or capture for many; fragmentation or flight by survivors into areas held by others, with whom they mixed or fought or finally displaced (Cabodevilla, 1994: p. 160) .”12

Once rubber shifted to the Napo, Quijos people around Tena and Archidona were quickly drawn into debt peonage on the fundos. In 1890, 2,000 indigenous families still lived near these towns (Oberem, 1980: p. 48) . But by 1924, Fr. Emilio Gianotti (1997) counted only around 50 runa families there, while another 60 inhabitants were scattered among former Jesuit settlements. Native communities in Loreto, Ávila, Coca and Concepción effectively ceased to exist as their inhabitants moved downriver or onto the San Miguel River.13 Meanwhile, Gianotti wrote, 4,700 mostly Quichua peons worked on 55 estates on the lower Napo River with (Map 3).14

Other than working on the fundos, their prospects were grim. They might become indebted laborers on the ten or so haciendas around Tena that produced aguardiente (rum), mainly for sale to rubber workers (García, 1909) . Or they might become “government people,” often (and misleadingly) called tamberos or indios libres. After 1895, President Eloy Alfaro’s Liberal Revolution brought a new wave of ambitious white officials and traders, eager to exploit the region’s most valuable natural resource: native labor. Under the Ley Especial de Oriente (1900), they commandeered all free Indian men for so-called public works projects.15 In theory, these men received a daily wage equivalent to US $.40; in practice, they were simply rented to the highest bidder and paid in lienzo (cloth) at inflated prices (if at all).16 Overwhelmingly, they chose the fundos. Economic life in the Napo river valleylargely became a contest over native workers that pitted señores ribereños against government authorities in Quito and their patronage appointees in Archidona or Tena.

Along the Pastaza and Curaray, Canelos Indians faced similar choices. At first, the Dominicans waged a successful campaign to exclude white merchants and rubber collectors. After 1895, however, Alfaro’s ministers revoked the missionaries’ civil authority and appointed their own officials in Sarayacu, Andoas and San Antonio on the Curaray. In 1906, the district commissioner reported that Canelos and Zápara men spent six to eight months a year along remote rivers harvesting caucho, while their wives and children tended cattle, sugarcane other crops for the ribereños (Bravo, 1907: pp. 61-63) . When rubber supplies in one place failed, indigenous tappers simply moved farther into the forest (Rice, 1903: p. 406) .17 Meanwhile, mission settlements at Sarayacu and Canelos remained virtually deserted, although Indians working in San Antonio occasionally made the eight-day journey upriver to bury their dead. By the late 1920s, ethnic identities in the Curaray Valley had converged (Cabodevilla, 1994: p. 235 ; Cabodevilla, 2010: p. 38 ; Hill, 1999: p. 741 ). After more than a century, “peaceful but uncivilized” Indian traders―a role filled earlier by Zápara and a few Jivaroans―had become Quichua-speaking peones on rubber estates.

And then, in 1930, international markets for Ecuadorian rubber collapsed. Señores ribereños in western Amazonia begged their buyers in Iquitos and Manaus to keep them afloat. But the markets in New York and London had dried up forever. Among native people, another “radical transformation” of ethnicity and economic roles was about to occur.

After the Boom: Conciertos and “Free Indians”, 1930-1960

In 1924, Fr. Gianotti (1997) counted around 700 Indians living at Armenia, the largest fundo on the Napo, while another 200 collected rubber for its owner on the Ucayali in Peru.18 By the 1930s, however, travelers and military officers regularly reported that the fundos had largely fallen into ruins (Holloway, 1932; Loch, 1938: p. 96 ; Samaniego & Toro, 1939) . Almost 5,000 ex-peones moved to the Upper Napo, where they settled in areas that had been depopulated a generation or two earlier: Coca, Loreto, Ávila, Tena, and the narrow valleys between Archidona and Baeza. Around 800 of them became conciertos (indebted workers) on sugar and cotton haciendas near Tena and Puerto Napo.19 But that left nearly 4,000 others with no way to support themselves except subsistence hunting and farming or panning for gold, while they bought supplies on credit from local patrones.20 Pre-existing forms of social and territorial organization had been largely destroyed by a half-century of “forced labor, fractured clans, ruptured families and communities, dispersion to unknown parts of the forest” (Cabodevilla, 1994: p. 143) . To mobilize this new workforce, white officials, merchants and landowners in the foothills set about modifying and reintroducing “traditional” institutions that undergirded an extensive system of labor control.21

Most often, Indians were compelled to work by need rather than terror. “Axes, machetes and shotguns had become essential for their own subsistence,” writes Muratorio (1991: p. 78) , “and textiles had become socially indispensable…The systematic use of terror was not required to make them work, although they were never free from abuses and systematic violence.” Violence included public whipping and the stocks, which were still found (half hidden) in Archidona and other places through the 1940s. More often, less overt coercion was used: for example, the Road Conscription Law (1944) and a system of internal passports that restricted Indian movements unless they were travelling on their employers’ behalf.22 Men who resisted found themselves in jail and were forced to work off their fines in projects assigned by the jefe político or his tenientes.23 “There is not one single free Indian living between the Napo and the Marañón,” wrote Gianotti in 1938 (quoted in Cabodevilla, 1994: p. 148 ). By the late 1940s, according to Hudelson (1981: p. 218) , Quichuas in Loreto and Ávila identified all Indians as gobierno runa (government people) or deudores (debtors), who worked on the haciendas.

For most native people, avoiding forced labor―for example, by fleeing into remote areas―was not an easy option. Within each district (tenencia política), white commissioners named one or two police agents (celadores or guardas) who were responsible for assembling native work gangs and overseeing their tasks: delivering supplies to remote outposts, building roads and bridges, or doing field labor. Generally speaking, celadores depended on indigenous officials known as justicias, capitanes or guaynaros to provide the workers.24 In theory, workers received a fixed wage that was deposited ahead of time in the district office. In practice, white officials usually paid the justicias or capitanes in cheap cloth, beads, needles or other goods for distribution among the work crew. It is difficult to say how much they received or what it was really worth.

In 1937, Shell Oil arrived to explore for oil in the Oriente. At first, it met the governor’s demand to hire manual laborers through their patrones, not on the open market.25 But the landowners often cheated, so Shell hired its own contractor and told him to recruit laborers among “free Indians” in the foothills. Indignant landowners filed a complaint with the district commissioner―who was, after all, also a landowner.26 It is difficult to know how this conflict would have been resolved because Shell ended its operations in 1947 without finding much oil. Yet 30 years later, both Whitten (1976: p. 254) and Muratorio (1991: p. 167) interviewed Canelos and Quijos Indians who recalled being paid the legal minimum wage in cash for the first time while working for Shell or its contractors.27Among Quijos people in Loreto y Ávila, Hudelson (1981: p. 219) recorded similar memories: “in the early 1940s, many Quichua Indians…enjoyed the novel experience of travelling freely” in the Oriente.

Once Shell departed, white landowners and political officials quickly reasserted their control over the company’s Quichua laborers. Yet Shell had unintentionally set in motion a chain of events that within ten years largely ended concertaje (debt labor) throughout the Andean foothills. Before it left, it was required by the government to build a road from Ambato in the highlands to Puyo, and then onward to the Napo itself.28 Now landowners along the road could raise cattle, tea and other commercial crops for sale in Quito or Guayaquil. As the unpaved roadway advanced toward Tena and Archidona, white residents north of the Napo filed homesteading claims along its projected route; runa families soon followed suit.29

Settlement and Population Growth on the Frontier, 1960-2010

By the early 1960s, white landowners no longer measured their wealth in Indians; instead, they calculated it in pastureland. Far better to hire a few men from “free” indigenous communities when they were needed than to maintain a large indebted labor force.30 Through the 1930s, for example, nearly 1,500 peones worked on Hacienda Ila, which grew sugarcane, cotton and many other products. By the mid-1960s, however, only seven native families still tended 350 head of cattle there (Angel Misueta in Dall’Alba, 1992: p. 166 ).

In turn, indigenous households staked out unclaimed territory and also raised livestock or commercial crops. Legal title to their land was often held by the leaders of each extended family and close relatives, who competed intensely with neighboring groups for favorable boundaries. In each community, one or two family names― marking territorial boundaries―predominated (Dall’Alba, 1992: p. 54) . Rights to gold panning, fishing, gardening and hunting were strictly enforced (Macdonald, 1997: pp. 47-50) . A new phase of “retribalization” had begun, organized around newly empowered elders with access to land and the government officials who controlled property rights (cf. Whitten, 1976: p. 125 ; Macdonald, 1999: p. 54 ).

From the 1930s onward, settlement on the Amazonian frontier closely followed―or rather, anticipated―the expanding road system ( Casagrande et al., 1964: p. 295 ; see also Whitten, 1976: pp. 205-264 ; Macdonald, 1999: p. 57 ). In 1963, Ecuadorian officials drew up ambitious plans to transform the Andean foothills into a prosperous agricultural zone (JNPC, 1963) . By this time, the road from Puyo to Tena―muddy but generally passable― extended toward Baeza and Quito (JNPC, 1963) . Within four years, a consortium of petroleum companies led by Texaco announced that it had found oil near the Colombian border and―responding to pressure from the Ecuadorian government―began building a major highway between Baeza and Lago Agrio. Even before the highway was completed in 1972, it provided access to new areas of settlement in the northern Oriente and allowed the government to implement part of its 1963 plan ( Wasserstrom & Southgate, 2013 ; see also Bromley, 1972: p. 288 ; Robinson, 1971 ). According to Hiraoka and Yamamoto (1980: p. 427) , the highway eventually opened 1.5 – 2.0 million hectares to colonization extending as far south as Méndez in Morona Santiago Province. By the time colonization ended in 1994, around 110,000 people had moved into the rainforest from other parts of Ecuador. In 2010, total population there reached nearly one million (Figure 1).

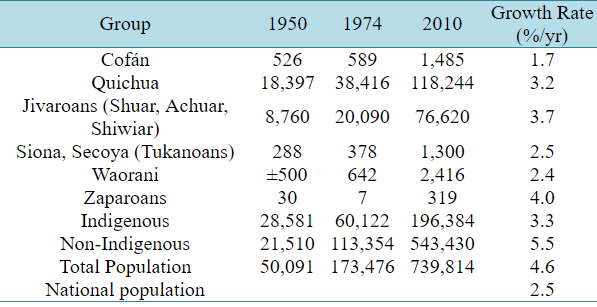

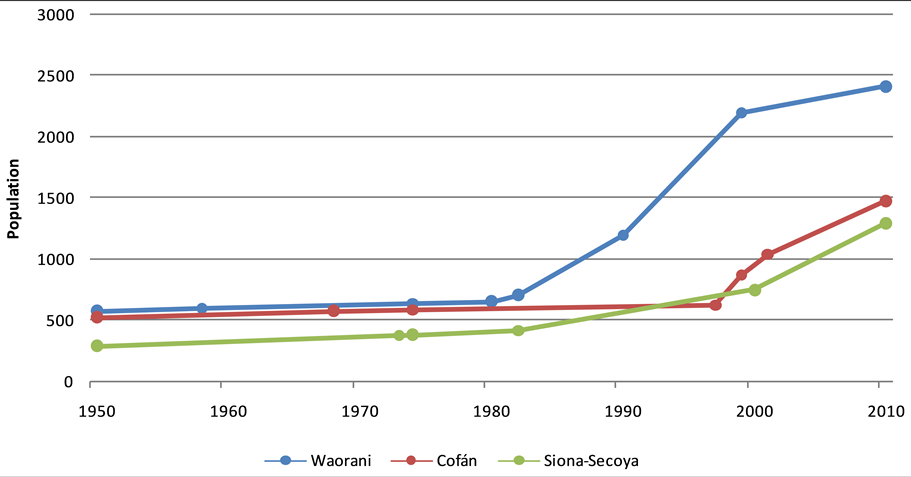

New roads also brought access to antibiotics, occasional wage labor, canned food, and in some cases, schools and clinics. As a result, Indians in Ecuador, like other native groups throughout the Amazon Basin, began to recover from their long demographic decline (Grenard & Grenard, 2000 ;McSweeney & Arps, 2005 ). Between 1950 and 2010, the indigenous population there grew at an annual rate of 3.5%, from 24,300 to 196,000 people― far higher than the country’s overall increase of 2.5% (Table 1). Even smaller, more isolated groups―the Cofán, the Siona-Secoya and the Waorani―expanded significantly as contact with missionaries and other outsiders became more frequent (Figure 2).

Throughout the 1960s, competition for land rights and road access among Indians in the Andean foothills intensified. Even before the road to Baeza was completed, migrants from elsewhere began to settle around Tena and Archidona (Macdonald, 1999: p. 87 ; Perreault, 2002: pp. 67-68) . By 1968, indigenous families with few prospects at home left for the northeastern forests and hoped that a road would follow them soon. Yet moving to the rainforest offered only short-term relief. “By the time the road arrives…” write Rudel and Horowitz (1993: p. 133) , quoting an extension agent, “the lands are tired.” Within a few years, Quichua migrants on the frontier were again running out of space. By 1998, nearly two-thirds of migrant households had at least one son who was farming elsewhere (Barbieri & Carr, 2005: p. 100) .

Population growth, competition for land, agricultural expansion and oil development brought new “sociopolitical formations” and ethnic divisions to the Andean foothills. Beginning in the 1960s, native communities formed regional and provincial federations to petition for land or protect it from expropriation (Rogers, 1996: p. 81; Perreault, 2003b: pp. 592-593 ; Erazo, 2013 ). Through the 1970s and 1980s, these communities obtained legal recognition as communes, cooperatives or centros and often received financial support from international donors (Bebbington & Ramón, 1992; Perreault, 2003a: pp. 70-71 ; Perreault, 2003c: pp. 340-341 ; Erazo, 2013: pp. 60-96) . Novel lines of authority were drawn as older family heads contested power with younger functionaries holding local or federation offices (Macdonald, 2002 ; Hutchins, 2007 ; Hutchins, 2010 ; Erazo, 2013 ). Previously unfamiliar forms of inequality and factional politics subsumed earlier competition among extended families ( Rogers, 1996: pp. 83-85 ; Perreault, 2003d: p. 105; Luque, 2008: p. 62; Wilson, 2002 ; Wilson, 2010: pp. 234-242) .

By the 1990s, communal identities based on family ties had mostly given way to membership in organizations affiliated with the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon ( CONFENIAE ), a major political group. Since then, younger Indian leaders have broadened their focus from simply protecting community land to questioning the role of government in modernizing inequality and perpetuating subordination. As Macdonald observes (2002: p. 177) , “They thus shifted course away from requests for government favors, limited participation, and individual land titles, toward a more expanded playing field in which entire groups engaged the state on basic priorities and practices.” Increasingly, ethnic identity has been redrawn along federation and regional lines, not local territories.

Conclusions: Ethnogenesis and Commodity Cycles

In Europe and the People without History, Eric Wolf (1982: p. 353) provided a useful starting point to resolve one of historical anthropology’s key paradoxes: Why did the expansion of European capitalism since the late 18th century generate seemingly pre-capitalist forms of labor relations―for example, plantation slavery and debt servitude―in other places? The case presented here allows us to reexamine this issue and explore its relationship to identity formation and population growth in northeastern Ecuador.

As Brown and Fernández (1992: p. 176) have written, “…the interest of the state in frontier regions such as the Upper Amazon is typically spasmodic, growing and ebbing in response to large-scale economic processes in the metropole…” Beginning in 1750, disintegration of the Jesuit missions brought about extensive “tribalization” of their former residents (Taylor, 1999: pp. 230-246) . More than a century later, Jiménez de la Espada (1998 [1927-1928]: p. 110) noted the sharp ethnic boundaries that marked his route from Baeza to the Napo; and like most observers, he assumed that they had existed since time immemorial. Quichua-speaking Indians would travel only within their own territories and always carried their own provisions. They neither gave nor expected food from other Quijos, unless they were directly related by kinship.

Such boundaries were swept away by the quinine and rubber booms 30 years later. From 1875 onward, Ecuador’s Amazon region produced quinine, rubber, cotton, sugar, cattle and eventually oil for national and international trade (Cuvi, 2011) . Detribalized Quichua-speakers worked as rubber tappers alongside Zápara, Cofán, Siona, and others throughout the western Amazon. Rubber was a risky business, subject to price fluctuations, high transportation costs, shipwrecks, oligopolistic buyers and other challenges (Barham & Coomes, 1996: p. 68) . With a little bad luck, even white caucheros might end up as indebted peons (Woodroffe, 1914; Yungjohann, 1989 [1916]) . Seemingly archaic modes of production and social relations based on debt (repartos) or unfree labor did not precede commodity booms; they were created by them. In effect, debt peonage spread the risks of rubber collection to indigenous workers―just the way that sharecropping in the Southern U.S. spread the risks of cotton production to poor farmers in the same years (Foner, 1988) .

With little power to bargain or resist, indigenous peones in the western Amazon were especially vulnerable. Their reemergence as distinct ethnic groups after 1930 represents a remarkable example of cultural regeneration. “In each of these cases,” Whitehead (1992: pp. 134-135) has written, “specific tribal identities have been shaped by the slow and tenuous expansion and contraction of …states in the region, notwithstanding their geographic distance or relative isolation from these states.” Eventually, such arrangements underwent further change, as new roads were built and commercial agriculture expanded in the 1950s and 1960s. Even so, debt labor persisted far from the roads until oil companies began to pay the legal minimum wage in 1964 (Beghin, 1963; Dall’Alba, 1992: pp. 178-179) .

Ethnogenesis, writes Jonathan Hill (1996: p. 1) , arises from “an ongoing process of conflict and struggle over a people’s existence and their positioning within and against a general history of domination…” As Whitten (2011: p. 9893) points out, similar trends continue today. “In the late twentieth to early twenty-first centuries processes of ethnogenesis are well under way in this region, as myriad people once submerged in the realm of ‘Runa’ cultural orientations again emerge as distinct, although usually Quichua-speaking, peoples…” In lowland Ecuador, ethnic identities have enabled indigenous people to rebuild once the storm tide of gold or rubber or perhaps oil has receded. In more recent times, they have also strengthened native claims to land, political participation and citizenship (cf. Reeve, 2014) . Yet we cannot understand this process without also understanding the competing elites who have dominated Amazonian society: landowners, caucheros, merchants, government officials, missionaries, soldiers, oil men.

Anthropologists have tended to view elites as relatively remote agents of the state―but elite interests were seldom aligned and they often competed fiercely for control of Indian labor. Conflict among elites often shaped the Oriente’s economic and social relations. It is incorrect to attribute such relations simply as the on-again, off-again tug of formal government institutions. Unravelling this complex puzzle remains one of the most difficult and significant challenges of historical anthropology in the western Amazon.

Appendix

Notes

1One important exception should be noted. In the 17th and 18th Centuries, Jesuits along the Aguarico and Upper Putumayo Rivers were replaced by Franciscans, who used local languages―especially Cofán and Siona―instead of Quichua. Native communities there maintained distinctive cultural and linguistic identities.

2Repartos involved the forced sale of cheap trade goods (primarily cotton cloth, beads and metal tools) on credit at inflated prices to Indian families. Indians were then required to repay this debt with gold, smoked fish, pita fiber, tobacco, salt and curare.

3According to Taylor (1999: p. 239) , Zápara populations had been reduced to a few hundred after 1760 due mainly to epidemics and Portuguese slave raiding.

4In this article, we largely exclude discussion of events among Shuar or Achuar groups (also known as “Jívaro” or “Jivaroans”). Interested readers should consult Harner (1972) ; Descola (1981) ;Taylor (1981) ; Bennett Ross (1984) ; Steel (1999) ; and Rudel and Horowitz (1993) .

5By this time, Harner writes (1972: p. 27) , western Shuar families had established peaceful trading relationships with mestizos in Macas (known as “Macabeos”). They no longer depended on Zápara intermediaries for tools and other goods. Harner also points out that shrunken heads (tsantsas) quickly became a valuable commodity in trade between Macabeos and Shuar, further increasing their incentives to raid other Indians. Within a few years, according to Bennett Ross (1984: p. 92) , they had “totally exterminated” native groups living along the old trail from Macas to Canelos.

6In fact, one of these ruined merchants, Faustino Lemos Raya, assassinated Conservative President Gabriel García Moreno, who had invited the Jesuits back into Ecuador (see Henderson, 2008: pp. 222-223 ).

7Similar patterns of interethnic or intraethnic slave raiding emerged intermittently throughout the western Amazon over the next half-century. In Peru, for example, Brown and Fernández (1991: pp. 59-60) describe widespread raiding among Ashinánika groups and the growing market for children as white settlement expanded.

8Rubber in the Andean foothills region was generally known as caucho and balata. It was harvested from Castilloa and Manilkara trees, not Hevea, as in Brazil. Ecuadorian rubber seldom involved outright slavery, as did Hevea collection farther down the Marañón River. For further discussions, see Stanfield (1998) , Santos Granero and Barclay (1999) and Wasserstrom (2014) .

9By 1905, officials in Quito had become alarmed at declining Indian populations along the Upper Napo and their transfer to Peru. In a letter to Carlos A. Ribadeneyra, a prominent cauchero and Liberal politician who served as district commissioner in Archidona, one of them remonstrated: “With great surprise and no less distress, I must object to your order to seize the Indians in San José and Loreto and forcibly send them in work gangs with your Colombian agents, Miguel Canchala, Domingo González, his brother Blas N., Juan Lucas, José Argüello, Abraham Lomas, Luis Cahuatigo, etc., to collect rubber with no other compensation after a long and difficult captivity than a few yards of cloth. If they resist, they are to be bound and sold to other whites below the Aguarico [in Peru].” Archivo de la Gobernación de Napo (Tena, Ecuador; hereafter AGN), “Carta del Ministerio de Instrucción Pública, Sección de Oriente, al Sr. Jefe Político del Cantón Napo [Carlos A. Ribadeneyra], 22 de mayo de 1906.” Muratorio (1991: pp. 99-121) cites similar documents.

10According to Genaro García (1909: pp. 20-21) , total sales of Ecuadorian rubber in Iquitos reached $100,000 in 1909, equivalent to $2.6 million at today’s exchange rates.

11 Reeve (1988: pp. 22-25) , Trujillo (2001: pp. 204-240) and Rival (2002) have written useful descriptions of the Rubber Boom along the Curaray. Cabodevilla’s account (1994: pp. 217-267)remains the best overall discussion of events there. For first-hand reports from the Dominican superior, see Magalli (1889; 1890) .

12 Harner (1972) , Bennett Ross (1984) and Steel (1999) have described how changing patterns of trade and warfare during these years dramatically reordered ethnic boundaries among Jivaroan groups in the Upano Valley and along the upper Marañón River.

13As early as 1892, Tovía reported that the Indian population of Coca had dropped from 40 or 50 families to seven (Tovía quoted in Cabodevilla, 1996: p. 217 ; see also Tovía, 1893) . “Around 1900, almost the entire population of Loreto, Concepcion, Ávila and San José was taken to Iquitos by rubber traders …Later, the Ron, Cox and Rodríguez families came and kidnapped them at night for their own estates or for sale to other caucheros. Loreto and Avila were almost completely depopulated” (Fernando Andrade in Dall’Alba, 1992: p. 53 ). Meanwhile, virtually the entire population of Archidona worked on two haciendas, Tzatzayacu and La Delicia (Eloy Baquero, Salvador Motzo and Pedro Grefa in Dall’Alba, 1992: pp. 143-144 ; Guillermina Martínez de Chamorro in Dall’Alba, 1992: p. 173 ). In 1918, the deputy commissioner in Coca reported to his superior that only 217 Indians (around 54 families) remained in the entire district: 57 in Payamino, 131 in Ávila and 83 in San José; Coca and other nearby communities were completely abandoned. AGN, “Carta del Teniente Político de Coca al Señor Jefe Político, 12 de noviembre de 1918.” By 1920, most of them had been taken to the San Miguel River along the border with Colombia. AGN, “N. 7 al Encargado de la Jefatura Política del Napo, 27 de agosto de 1925.” According to Barral and Orrego (1978: p. 16 ; see also Muratorio, 1991: p. 116) , more than 100 families were brought from around Tena by a Colombian rubber collector named Logroño. Foletti Castegnaro (1985: pp. 165-175) interviewed their descendants a half-century later. In the late 1970s, Hudelson (1981: p. 216) found that Quichua surnames from Ávila and Loreto were still widely used among Indians on the lower Napo in Peru (see also Dall’Alba, 1992: p. 54 ). Mercier (1979: pp. 243-247) recorded extensive oral accounts of migration from Loreto, Concepción and Cotapino “downriver with the patrones, during rubber times.” Finally, Trujillo (2001: pp. 225-230; also p. 240) describes widespread deployment of laborers from the upper Napo on haciendas along the lower Curaray and Cononaco Rivers.

14Gianotti’s 1924 census in Italian, entitled “Statistica d’Oriente. Rio Napo (1928) ,” remains unpublished. The authors thank Miguel Angel Cabodevilla for allowing us to summarize it. Excerpts from Gianotti’s reports (1997) are available in Spanish.

15AGN preserves abundant documentation through the 1930s on payment terms for “free Indians” drafted into public works projects. In 1934, for example, Indians who carried 35 kg loads from Baeza to Tena or Archidona were paid 50 centavos (US $.08) per day. They were also required to provide food for any white traveler who demanded it. AGN, “Oficio del Jefe de la Comisión [Militar] de Puerto Napo al Jefe Político del Cantón Napo-Curaray, 23 de febrero de 1934.”

16Payment in cloth. In 1906, Bravo (1920: p. 96) noted that Indians in Villano were paid a daily wage of “two varas [approximately two yards] of cloth,” along with rations of yucca and bananas. In 1910, a yard of cloth was valued at S/. 0.25 (US $.07). AGN, “Oficios del Ministerio de Instrucción Pública, Sección Oriente, al Gobernador de Oriente, 27 de septiembre y 24 de diciembre de 1910.” In 1925, Indians who carried mail throughout the province―often requiring arduous overland treks and river journeys of a month or more―were still paid in cloth, although the practice was supposedly prohibited. AGN, “Solicitud al Administrador de Correos, 16 de septiembre de 1925”; “Oficio del Teniente Político de Rocafuerte al Jefe Político, 31 de agosto de 1925”; also AGN, “Carta del Jefe Político de Tena al Señor Teniente Político de Archidona, 10 de julio de 1921.” Free Indians rented to private landowners. Many examples could be cited. In 1934, authorities ordered 44 free Indians from Tena and Archidona to deliver supplies to the Hacienda Vargas Torres―an eight-day trip for which they received a credit of three sucres (US $.48) toward a yearly labor assessment imposed by the government for public works and other projects. AGN, “Personal que ha [illegible], firmado por el Jefe Político, 31 de diciembre de 1934.” Two years later, the Director General de Oriente in Quito reproached his deputy commissioner in Archidona for providing Indians to “people who already have their own peones”; instead, he admonished,”free Indians” should be reserved for settlers “who truly need them.” AGN, “Carta del Jefe Político del Cantón Napo al Teniente Político de la Parroquia de Archidona con transcripción de radiograma, 11 de marzo de 1936.” His order was ignored.

17This was also true along the Napo. In 1903, Rice described a large expedition of 40 Indians departing from Berna in 12 canoes. Berna was a fundo near Cocaowned by Samuel and Silverio Roggeroni. The Indians were headed up the Tiputini to spend a year collecting caucho.

18Many Ecuadorian caucheros took their Indians to Peru, either permanently or for extended periods. See AGN, “Carta del Jefe Político del Cantón Pastaza al Señor Gobernador del Oriente, 25 de enero de 1909”; “Carta de M. E. Escudero, Ministerio de Educación Pública, Sección Oriente, al Señor Jefe Político del Cantón Napo-Curaray, 21 de abril de 1917.” As late as 1925, the Director General de Oriente in Quito wrote: “I approve the proposal from the tenientes políticos of La Coca and Loreto to transport Indians to the Putumayo and Brazil, because such activity is not prohibited, nor could it be prohibited, by any ministerial order.” AGN, “N. 7 al Encargado de la Jefatura Política del Napo, 27 de agosto de 1925.”

19AGN, “Libros de Cuentas, 1938.” In the mid-1930s, according to a former manager of Hacienda Ila, “we had more than 100 tambos of indebted laborers with three or four families living in each one…All of the laborers on the left bank of Anzu worked for D. Carlos Sevilla” (José Rosendo Peña Flores in Dall’Alba, 1992: pp. 39-40 ).

20See AGN, “Oficio No. 2 del Jefe Político del Cantón Napo al Teniente Político de la Parroquia de Napo, 5 de junio de 1950.” In 1946, the deputy commissioner in Puerto Napo reported that 4,000 free Indians lived in his district near Tena. AGN, “Carta del Teniente Político de Puerto Napo, Rudolfo Rodríguez F., al Sr. Jefe Político del Cantón, 2 de agosto de 1946.” Macdonald (1999: p. 54) reports that each muntun (group of interrelated families living around a shaman or other leader) was indebted to a specific landowner or trader. When members changed residence, they “frequently also tried to establish ties with their new muntun’s patron.” These arrangements persisted into the 1960s.

21On labor control, see AGN, “Cuadrilla No. 24, 18 de enero de 1923”; “Carta de A. Ramírez al Jefe Político del Cantón Napo-Aguarico, 2 de marzo de 1923.” Dozens of similar documents can be found in AGN.

22Pasaportes Orientales were issued systematically from 1932 onward, as native workers left the rubber estates. They resembled vagrancy laws in the U.S. and the pass system in South Africa. In AGN, they are catalogued by year, e.g., “Pasaportes 1932,” etc. Additional descriptions of the government labor system can be found in AGN, “Miscelánea, No. 16, 1933; G. Danzo, Miscelánea, 1929,” as well as many other documents.

23For similarities with convict labor in the U.S. South, see Blackmon (2008) .

24AGN, “Carta [unsigned] al Teniente Político de Archidona, 24 de julio de 1934”; “Carta de la Tenencia Política de Loreto al Jefe Político del Cantón Napo, 15 de marzo de 1941”; see alsoHudelson (1981: pp. 218-219) . Oberem (1980: pp. 230-233) describes how this system functioned functioned in Tena and Loreto through the 1940s.

25Indebted workers were frequently rented by their patrones to the government or others for all sorts of reasons. A typical example can be found in AGN, “Carta del Teniente Político Alfonso Cadena al Señor Esteban Quevedo, Ayudante de Colonias de la Hda., 4 de julio de 1934.”

26AGN, “Carta al Señor Superintendente del Campo Arajuno del Gobernador de la Provincia de Napo-Pastaza, 20 de enero de 1945”; “Acta de Enganche de Trabajadores Suscrita entre los Enganchadores de Tena, Archidona y Napo, ante del Señor Gobernador de la Provincia y en Presencia del Señor Enrique Illingworth, 3 de junio de 1945”; “Carta al Sr. Ministro de Gobierno y Oriente [unsigned], 24 de julio de 1946” et seq. In 1949, one landowner complained to Blomberg (1957: p. 151) that Indians had become “impudent and lacking in respect” because Shell was paying high wages and requiring only eight-hour workdays.

27According to Cabodevilla (1994: p. 36) , Shell paid eight sucres per day, whereas local landowners paid one sucre for agricultural labor (usually in overvalued merchandise). By 1941, Indian porters received five sucres a day for 80 – 100 lb loads (36 – 45 kg)―still less than the legal limit of eight sucres for 70 lbs. (32 kg) (Miguel Angel Cujano Chasin in Dall’Alba, 1992: p. 120 ). “Unintentionally,” writes Cabodevilla (2010: 75) , [the oil industry] became a primary force in ending concertaje, with Indian slaves who earned a few pieces of cloth per year.”

28According to Casagrande et al. (1964: pp. 295-296) , work on the Puyo-Tena extension of Shell’s road began in 1950 and continued into the early 1960s.

29Throughout the 1950s, numerous petitions from Quichua family heads were filed with authorities in Tena and Quito. Examples include AGN, “Petición al Señor Jefe Político y Juez Cantonal, firmada por Juan Cerda, 24 de julio de 1950”; “Acta de Linderación, 8 de diciembre de 1951”; AGN, “Cartel…del Señor Sisafio Grefa ha solicitado…1953; AGN, “Acta de Transacción, 1953”; AGN, “Acta de Declaración de Linderos entre los indígenas Alonso Andi (a) Curaray y Domingo Andi (a) Huynana, abril de 1952”; AGN, “Acta de Demarcación entre los Indígenas Bartolo Tanuy (a) Manduro, Francisco Tanuy (a) Mango, Domingo Tanuy (a) Lagarto y Bartolo Tanuy (a) Malta, Tena, 20 de septiembre de 1952”; AGN, “Acta de Linderación, Tena, 23 de diciembre de 1952.”

30Even so, debt labor persisted far from the roads until oil companies began to pay the legal minimum wage in 1964 ( Beghin, 1963 ; Dall’Alba, 1992: pp. 178-179 ).

References

- Almagro, M. (1866). Breve descripción de viajes hechos en América por la Comisión Científica enviada por el Gobierno de S.M.C. durante los años de 1862 a 1866. Madrid: Imprenta de M. Rivadeneyra.

- Alomía, A. (1936 ). La Defensa del Oriente Ecuatoriano. Quito: Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores.

- Barbieri, A. F., & Carr, D. L. (2005). Gender-Specific Out-Migration, Deforestation and urbanization in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Global and Planetary Change, 47, 99-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2004.10.005

- Barham, B., & Coomes, O. (1996). Prosperity’s Promise. The Amazon Rubber Boom and Distorted Economic Development. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Barral, H., & Orrego, C. (1978). Informe sobre la colonización en la Provincia del Napo y las transformaciones de las sociedades indígenas. Quito: Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería.

- Bebbington, A., & Ramón, G. (Eds.) (1992). Actores de una Década Ganada: Tribus, Comunidades y Campesinos en la Modernidad. Quito: COMUNIDEC.

- Beghin, F. J. (1963). Putumayo. Napo. Pastaza. Informe general de las investigaciones y estudios realizados sobre la Región Oriental por el etnólogo Francisco Javier Beghin, de conformidad con lo establecido en el contrato suscrito por el Señor Director del I. N. C. con el referido etnólogo. Quito: Instituto Nacional de Colonización.

- Bennett Ross, J. (1984). Effects of Contact on Revenge Hostilities among the Achuara Jívaro. In R. B. Ferguson (Ed.), Warfare, Culture and Environment (pp. 83-109). New York: Academic Press.

- Blackmon, D. (2008). Slavery by Another Name. The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York: Anchor Books.

- Bravo, V. (1907). Viaje al Oriente de Quito al Curaray (1). Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Lima, 21, 48-67.

- Bravo, V. M. (1920). Viaje al Oriente: Segunda Parte. En la Región del Curaray―1906. Quito: Imprenta del E. M. G.

- Bromley, R. (1972). Agricultural Colonization in the Upper Amazon Basin. The Impact of Oil Discoveries. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 63, 278-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.1972.tb01179.x

- Brown, M. F., & Fernández, E. (1991). War of Shadows: The Struggle for Utopia in the Peruvian Amazon. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520074354.001.0001

- Brown, M. F., & Fernández, E. (1992). Tribe and State in a Frontier Mosaic: The Ashánika of Eastern Peru. In R. B. Ferguson, & N. Whitehead (Eds.), War in the Tribal Zone (pp. 175-198). Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research.

- Cabodevilla, M. A. (1994). Los Huaorani en la historia de los pueblos del Oriente. Coca: CICAME.

- Cabodevilla, M. A. (1996). Coca. La Región y su Historia. Coca: CICAME.

- Cabodevilla, M. A. (2010). La Nación Waorani. Noticias históricas y territorio. Orellana: Vicariato Apostólica de Aguarico.

- Casagrande, J. B., Thompson, S. I., & Young, P. D. (1964). Colonization as a Research Frontier: The Ecuadorian Case. In R. A. Manners (Ed.), Process and Pattern in Culture (pp. 281-325). Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company.

- Castrucci de Vernazza, M. (1849). Viaje practicado desde El Callao hasta las misiones de las dos tribus de infieles záparos y gívaros. Lima: Imprenta de Justo Montoya.

- Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (CONFENIAE) (1995). Tierras y Territorios Indígenas en la Amazonía: Elementos Jurídicos para un Diagnóstico Regional. La Cuestión Indígena en Ecuador. Volume III, Anxex IV. Cuadro E-1. In Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores del Perú/Tratado de Cooperación Amazónica-Secretaría Pro Tempore. Lima: Ministerio Exteriores del Perú.

- Consejo de Desarrollo de las Nacionalidades y Pueblos del Ecuador (CODENPE) (2003). Diagnóstico de la Nacionalidad Huaorani. http://www.codenpe.gov.ec/waorani.htm

- Cuvi, N. (2011). The Cinchona Program (1940-1945): Science and Imperialism in the Exploitation of a Medicinal Plant. Dynamis, 31, 183-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0211-95362011000100009

- Dall’Alba, L. (1992). Pioneros, nativos y colonos. El Dorado en el siglo XX. Quito: Ediciones Abya Yala, Petroecuador y Misión Josefina del Napo.

- Descola, P. (1981). From Scattered to Nucleated Settlement: A Process of Socioeconomic Change among the Achuar. In N. Whitten (Ed.), Cultural Transformations and Ethnicity in Modern Ecuador (pp. 614-646). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Erazo, J. (2013). Governing Indigenous Territories. Durham: Duke University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9780822378921

- Esvertit, N. (2008). La incipiente provincial. Amazonia y Estado ecuatoriano en el siglo XIX. Quito: Universidad Andina Simón Bolivar.

- Ferguson, R. B., & Whitehead, N. L. (1992). The Violent Edge of Empire. In R. B. Ferguson, & N. Whitehead (Eds.), War in the Tribal Zone (pp. 1-30). Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research.

- Fitton, L. J. (1999). Is Acculturation Healthy? Biological, Cultural, and Environmental Change among the Cofán of Ecuador. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University.

- Foletti Castegnaro, A. (1985). Tradición oral de los Quichuas Amazónicos del Aguarico y San Miguel. Quito: Ediciones Abya Yala.

- Foner, E. (1988). Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: Harper & Row.

- Fuentes, H. (1908). Loreto. Apuntes geográficos, históricos, estadísticos, políticos y sociales, Vol. II. Lima: Imprenta de La Revista.

- Gamarra, M. del P. (1996). La frontera nómada: Frentes y fronteras económicas en el proceso cauchero ecuatoriano (1870-1920). Revista Ecuatoriana de Historia, 9, 41-77.

- García, G. (1909). Informe del Gobernador de la Provincia de Oriente al Ministerio de Instrucción Pública y Oriente. Quito: Tipografía de la Escuela de Artes y Oficios.

- Gianotti, E. (1928). Statistica d’Oriente. Río Napo. Coca: Fundación Labaka.

- Gianotti, E. (1997). Viajes por el Napo: Cartas de un misionero. Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala.

- Golub, A. (1982). The Upper Amazon in Historical Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, New York: City University of New York.

- Grenard, P., & Grenard, F. (2000). Equatorial America. In S. Bahuchet (Ed.), The Situation of Indigenous Peoples in Tropical Forests. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. http://lucy.ukc.ac.uk/Sonja/RF/Ukpr/Report.htm

- Harner, M. J. (1972). The Jívaro: People of the Sacred Waterfalls. Garden City: Doubleday/Natural History Press.

- Henderson, P. V. N. (2008). Gabriel García Moreno and Conservative State Formation in the Andes. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Hill, J. (1996). Introduction. In J. Hill (Ed.), History, Power, and Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Americas, 1492-1992 (pp. 1-19). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press.

- Hill, J. (1999). Indigenous Peoples and the Rise of Independent Nation-States in Lowland South America. In F. Salomon, & S. B. Schwartz (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. III, Part 2: South America (pp. 704-764). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hiraoka, M., & Yamamoto, S. (1980). Agricultural Development in the Upper Amazon of Ecuador. Geographical Review, 70, 423-445. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/214077

- Holloway, H. L. (1932). East of the Ecuadorian Andes. Geographical Journal, 80, 410-419. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1784228

- Hudelson, J. (1981). The Expansion and Development of Quichua Transitional Culture in the Upper Amazon Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, New York: Columbia University.

- Hutchins, F. (2007). Footprints in the Forest: Ecotourism and Altered Meanings in Ecuador’s Upper Amazon. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology, 12, 75-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/jlat.2007.12.1.75

- Hutchins , F. (2010). Ecotourism, Cultural Reproduction, and the Logic of Capital in Ecuador’s Upper Amazon. In F. Hutchins, & P. C. Wilson (Eds.), Editing Eden: A Reconsideration of Identity, Politics, and Place in Amazonia (pp. 3-37). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC) (1950-2010). Censos Nacionales de Población y Vivienda. Quito: INEC.

- Jameson, W. (1858). Excursion Made from Quito to the River Napo, January to May, 1857. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 28, 337-349. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1798328

- Jiménez de la Espada, M. (1998 [1927-1928]). Diario de la expedición al Pacifico llevada a cabo por una comisión de naturalistas españoles durante los años 1862 a 1865. Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica, 67-68, 1-246. (Madrid)

- Junta Nacional de Planificación y Coordinación Económica (JNPC) (1963). El aprovechamiento de la tierra y el mar, Tomo II, Reforma a la Estructura de Tenencia de la Tierra y Expansión de la Frontera Agrícola, Capitulo II, Colonización. Quito: JNPC.

- Kohn, E. (2013). How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520276109.001.0001

- Krupa, C. (2010). State by Proxy: Privatized Government in the Andes. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 52, 319-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S001041751000006X

- Loch, E. E. (1938). Fever, Famine and Gold. New York: G.P. Putman’s Sons.

- López, S., & Sierra, R. (2011). A Resource Demand Model of Indigenous Production: The Jivaroan Cultivation Systems of Western Amazonia. Agricultural Systems, 104, 246-257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2010.10.003

- Luque, J. (2008). Embracing the Past: Conflict, Conservation, and Organization in Ecuador’s Upper Amazon. Journal of Ecological Anthropology, 12, 54-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/2162-4593.12.1.4

- Macdonald, T. (1997). De cazadores a ganaderos. Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala.

- Macdonald, T. (1999). Ethnicity and Culture amidst New “Neighbors”: The Runa of Ecuador’s Amazon Region. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Macdonald, T. (2002). Ecuador’s Indian Movement: Pawn in a Short Game or Agent in State Reconfiguration? In D. Maybury-Lewis (Ed.), The Politics of Ethnicity: Indigenous Peoples in Latin American States (pp. 169-197). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Magalli, J. M. (1889). Carta Sobre la Misión Dominicana en Canelos. Quito: La Nación Y Cía.

- Magalli, J. M. (1890). Colección de Cartas sobre las Misiones Dominicanas del Oriente. Quito: Imprenta de Juan Pablo Sanz.

- McSweeney, K., & Arps, S. (2005). A “Demographic Turnaround”: The Rapid Growth of Indigenous Populations in Lowland Latin America. Latin American Research Review, 40, 3-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lar.2005.0012

- Mercier, J. M. (1979). Nosotros los Napu-Runa. Mitos e Historia de Indígenas de Perú. Iquitos: Centro de Estudios Teológicos de la Amazonía.

- Muratorio, B. (1991). The Life and Times of Grandfather Alonso. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Newson, L. A. (1995). Life and Death in Early Colonial Ecuador. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Oberem, U. (1980). Los Quijos: Historia de la transculturación de un grupo indígena en el Oriente Ecuatoriano. Otavalo: Instituto Otavaleño de Antropología.

- Orton, J. (1871). The Andes and the Amazon: Or, across the Continent of South America. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Osculati, G. (2003 ). Exploraciones de las regiones ecuatoriales a lo largo del Napo y del río de las Amazonas. Quito: Ediciones Abya Yala.

- Perreault, T. A. (2002). Movilización política e identidad indígena en el alto Napo. Quito: Ediciones Abya Yala.

- Perreault, T. (2003a). Changing Places: Transnational Networks, Ethnic Politics, and Community Development in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Political Geography, 22, 61-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(02)00058-6

- Perreault, T. (2003b). A People with Our Own Identity: Toward a Cultural Politics of Development in Ecuadorian Amazonia. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 21, 583-606. http://dx.doi.org/10.1068/d339

- Perreault, T. (2003c). Social Capital, Development, and Indigenous Politics in Ecuadorian Amazonia. Geographical Review, 93, 328-349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2003.tb00036.x

- Perreault, T. (2003d). Making Space: Community Organization, Agrarian Change, and the Politics of Scale in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Latin American Perspectives, 30, 96-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0094582X02239146

- Pierre, F. (1983 ). Viaje de exploración al Oriente Ecuatoriano―1887-1888. Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala.

- Porras, P. (1973 ). Los indios civilizados. Reprinted in Antropología. Cuadernos de Investigación, 9, 122-141.

- Reeve, M. E. (1988). Cauchu Uras: Lowland Quichua Histories of the Amazon Rubber Boom. In J. Hill (Ed.), Rethinking History and Myth: Indigenous South American Perspectives on the Past (pp. 19-34). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Reeve, M. E. (1994). Regional Interaction in the Western Amazon: The Early Colonial Encounter and the Jesuit Years: 1538-1767. Ethnohistory, 41, 106-138.

- Reeve, M. E. (2014). Amazonian Quichua in the Western Amazon Regional Interaction Sphere. Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America, 12, 14-27.

- Rice, A. H. (1903). From Quito to the Amazon via the Rio Napo. Geographical Journal, 21, 401-418. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1775681

- Rival, L. (1996). Hijos del Sol, padres del jaguar. Los Huaorani de ayer y hoy. Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala.

- Rival, L. (2002). Trekking through History. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Robinson, S. (1971). Sky Chief (Film). Antropología Visual. Universidad Metropolitana de México and University of California. http://www.antropologiavisual.net/2007/sky-chief/

- Robinson, S. (1979). Toward an Understanding of Kofan Shamanism. Ph.D Thesis, Ithaca: Cornell University.

- Rogers, M. (1996). Beyond Authenticity: Conservation, Tourism, and the Politics of Representation in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Identities, 3, 73-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.1996.9962553

- Rudel, T., & Horowitz, B. (1993). Tropical Deforestation: Small Farmers and Land Clearing in the Ecuadorian Amazon. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ruíz, L. (1997). El pueblo Cofán. In M. Ventura (Ed.), Etnografías mínimas del Ecuador (pp. 117-142). Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala.

- Samaniego, J., & Toro, J. (1939). Monografía de algunas poblaciones de la Región Oriental. Quito: Ministerio de Defensa Nacional.

- Santos Granero, F., & Barclay, F. (1999). Tamed Frontiers: Economy, Society and Civil Rights in Upper Amazonia, 1851- 1990. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Sawyer, S. (2004). Crude Chronicles: Indigenous Politics, Multinational Oil, and Neoliberalism in Ecuador. Durham: Duke University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9780822385752

- Simson, A. (1886). Travels in the Wilds of Ecuador, and the Exploration of the Putumayo River. London: S. Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington.

- Stanfield, M. E. (1998). Red Rubber, Bleeding Trees. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

- Steel, D. (1999). Trade Goods and Jívaro Warfare: The Shuar, 1850-1957, and the Achuar, 1940-1978. Ethnohistory, 46, 745-776.

- Taylor, A. C. (1981). God-Wealth: The Achuar and the Missions. In N. Whitten (Ed.), Cultural Transformations and Ethnicity in Modern Ecuador (pp. 647-676). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Taylor, A. C. (1994). El oriente ecuatoriano en el siglo XIX: “El otro litoral.” In J. Maiguashca (Ed.), Historia y Región en el Ecuador, 1830-1930 (pp. 17-68). Quito: FLACSO.

- Taylor, A. C. (1999). The Western Margins of Amazonia from the Early Sixteenth to the Early Nineteenth Century. In F. Salomon, & S. B. Schwartz (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. III, Part 2, South America (pp. 188-257). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tovía, G. (1893). Carta del R. P. Gaspar Tovía al Excmo. Sr. Dr. Don Luis Cordero sobre los últimos sucesos de la Provincia Oriental. Quito: Imprenta del Gobierno.

- Trujillo, J. N. (2001). Memorias del Curaray. Quito: Fondo Ecuatoriano Populorum Progresso.

- Uquillas, J. E. (1985). Indian Land Rights and Natural Resource Management in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In T. Macdonald Jr. (Ed.), Native Peoples and Economic Development: Six Case Studies from Latin America (pp. 87-103). Cambridge: Cultural Survival.

- Uzendoski, M. (2005). The Napo Runa of Amazonian Ecuador. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Vickers, W. T. (1981). The Jesuits and the SIL: External Policies for Ecuador’s Tucanoans through Three Centuries. In S. Hvalkof, & P. Aaby (Eds.), Is God an American? An Anthropological Perspective on the Missionary Work of the Summer Institute of Linguistics (pp. 51-62). Copenhagen: International Work Group on Indigenous Affairs and Survival International.

- Vickers, W. T. (2003). The Modern Political Transformation of the Secoya. In N. E. Whitten Jr. (Ed.), Millennial Ecuador (pp. 46-72). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press.

- Villavicencio, M. (1858). Geografía de la República del Ecuador. New York: R. Craighead.

- Wasserstrom, R., & Southgate, D. (2013). Deforestation, Agrarian Reform and Oil Development in Ecuador, 1964-1994. Natural Resources, 4, 31-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/nr.2013.41004

- Wasserstrom, R. (2014). Surviving the Rubber Boom: Cofán and Siona Society in the Colombia-Ecuador Borderlands (1875-1955). Ethnohistory, 61, 525-548. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/00141801-2681786

- Whitehead, N. L. (1992). Tribes Make States and States Make Tribes: Warfare and the Creation of Colonial Tribes and States in Northeastern South America. In R. B. Ferguson, & N. Whitehead (Eds.), War in the Tribal Zone (pp. 127-150). Santa Fe, NM: School of America Research.

- Whitten, N. (1976). Sacha Runa: Ethnicity and Adaptation of the Ecuadorian Jungle Quichua. Champaign-Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Whitten, N. (2011). Ethnogenesis and Interculturality in the “Forest of Canelos”: The Wild and the Tame Revisited. In A. Honborg, & J. D. Hill (Eds.), Ethnicity in Ancient Amazonia: Reconstructing Past Identities from Archaeology, Linguistics, and Ethnohistory (pp. 9641-9976). Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado (Kindle Edition).

- Wiener, C. (2011 ). El Amazonas y las Cordilleras, 1879-82. In J. Gómez Rendón (Ed.), Ecuador en las páginas de “Le Tour du Monde” (pp. 163-264). Quito: Consejo Nacional de Cultura.

- Wilson, P. C. (2002). Indigenous Federations, NGOs, and the State: Development and the Politics of Culture in Ecuador’s Amazon. Ph.D Thesis, Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh.

- Wilson, P. C. (2010). Indigenous Leadership and the Shifting Politics of Development in Ecuador’s Amazon. In F. Hutchins, & P. C. Wilson (Eds.), Editing Eden: A Reconsideration of Identity, Politics, and Place in Amazonia (pp. 218-245). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Wolf, E. (1982). Europe and the People without History. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Woodroffe, J. F. (1914). The Upper Reaches of the Amazon. London: Meuthuen & Co. Ltd.

- Yashar, D. (2005). Contesting Citizenship in Latin America: The Rise of Indigenous Movements and the Postliberal Challenge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790966

- Yungjohann, J. C. (1989 ). White Gold: The Diary of a Rubber Cutter in the Amazon 1906-1916. Oracle, AZ: Synergetic Press.

Originally published by Advances in Anthropology 1:5 2015), DOI:10.4236/aa.2015.51001 under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.