While 21st-century abortion debates often revolve around questions of life and personhood, this was not always the case.

By Alisha Palmer

PhD Candidate in English Literature

The University of Edinburgh

Introduction

You might be forgiven for thinking of abortion as a particularly modern phenomenon. But there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that abortion has been a constant feature of social life for thousands of years. The history of abortion is often told as a legal one, yet abortion has continued regardless of, perhaps even in spite of, legal regulation.

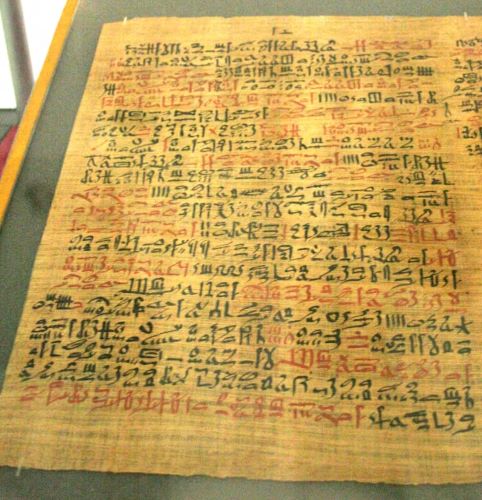

The need to regulate fertility before or after sex has existed for as long as pregnancy has. The Ancient Egyptian Papyrus Ebers is often seen as some of the first written evidence of abortion practice.

Dating back to 1600BC, the text describes methods by which “the woman empties out the conceived in the first, second or third time period”, recommending herbs, vaginal douches and suppositories. Similar methods of inducing abortion were recorded, although not recommended, by Hippocrates around the fourth century BC.

Part of the daily life of ancient citizens, abortion also found its way into their art. Publius Ovidius Naso, commonly known as Ovid, was a Roman poet whose collection of works Amores describes the narrator’s emotional turmoil as he watches his lover suffering from a mismanaged abortion:

While she rashly is overthrowing the burden of her pregnant womb, weary Corinna lies in danger of her life. Having attempted so great a danger without telling me. She deserves my anger, but my anger dies with fear.

Ovid’s concern at first is with the risk of losing his love Corinna, not the potential child. Later, he asks the gods to ignore the “destruction” of the child and save Corinna’s life. This reveals some important aspects of historical attitudes towards abortion.

While 21st-century abortion debates often revolve around questions of life and personhood, this was not always the case. The Ancient Greeks and Romans, for example, did not necessarily believe that a foetus was alive.

Early thinkers such as St. Augustine (AD354-AD430), for example, distinguished between the embryo “informatus” (unformed) and “formatus” (formed and endowed with a soul). Over time, the most common distinction became drawn at what was known as the “quickening”, which was when the pregnant woman could feel the baby move for the first time. This determined that the foetus was alive (or had a soul).

As a delayed period was often the first sign something was amiss, and a woman may not have considered herself pregnant until much later, a lot of advice on abortion would focus on restoring menstrual irregularities or blockages instead of terminating a potential pregnancy (or foetus).

As a result, much of the abortion advice throughout history does not necessarily mention abortion at all. And it was often down to personal interpretation whether or not an abortion had even taken place.

Indeed, recipes for “abortifacients” (any substance that is used to terminate a pregnancy) could be found in medical texts like those from the German nun Hildegard von Bingen in 1150 and in domestic recipe books with treatments for other common ailments well into the 20th century.

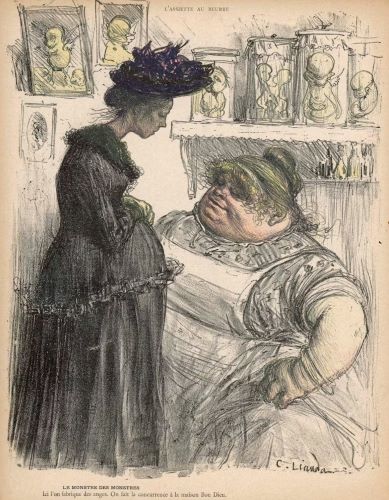

In the west, the quickening distinction gradually went out of fashion over the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet women continued to have abortions despite changing beliefs about life and the law. In fact, some sources claimed, they seemed to be more common than ever.

‘An Epidemic of Abortions’

In 1920, Russia became the first state in the world to legalise abortion, and in 1929, famous birth control advocate Marie Stopes lamented that “an epidemic of abortions” was sweeping England. Similar claims from France and the US also indicate a perceived uptick.

These claims accompanied a wave of plays, poems and novels that included abortion. In fact, in 1923, Floyd Dell, the US magazine editor and writer, published a new work of fiction, Janet March, where the main character complains about the number of novels that feature abortions, stating there “were dreadful things enough in novels, but they happened only to poor girls – ignorant and reckless girls”.

But the literature of the early 20th century, with many stories based on women’s real experiences, attests to a wider range of abortions than the stereotypical image of the poor and destitute backstreet operations of the 1900s.

For example, the English novelist, Rosamond Lehmann records a seductive “feminine conspiracy” of aborting women waiting with “tact, sympathy, pills and hot-water bottles”, in her 1926 novel The Weather in the Streets.

These texts form part of a long tradition of abortion storytelling that is a predecessor to contemporary activism. For example, We Testify is an organisation dedicated to the leadership and representation of people who have abortions. And Shout Your Abortion is a social media campaign where people share their abortion experiences online without “sadness, shame or regret”.

Abortion has a long and varied history, but above all these texts – from the Egyptian papyri of 1600BC to the social media posts of today – show that abortion has been and remains central to our history, our lives and even our art.

Originally published by The Conversation, 09.21.2023, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.