Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Boxing is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves, throw punches at each other for a predetermined amount of time in a boxing ring.

Amateur boxing is both an Olympic and Commonwealth Games sport and is a standard fixture in most international games—it also has its own World Championships. Boxing is overseen by a referee over a series of one-to-three-minute intervals called rounds.

A winner can be resolved before the completion of the rounds when a referee deems an opponent incapable of continuing, disqualification of an opponent, or resignation of an opponent. When the fight reaches the end of its final round with both opponents still standing, the judges’ scorecards determine the victor. In the event that both fighters gain equal scores from the judges, professional bouts are considered a draw. In Olympic boxing, because a winner must be declared, judges award the contest to one fighter on technical criteria.

While humans have fought in hand-to-hand combat since the dawn of human history, the earliest evidence of fist-fighting sporting contests date back to the ancient Near East in the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC.[2] The earliest evidence of boxing rules date back to Ancient Greece, where boxing was established as an Olympic game in 688 BC.[2] Boxing evolved from 16th- and 18th-century prizefights, largely in Great Britain, to the forerunner of modern boxing in the mid-19th century with the 1867 introduction of the Marquess of Queensberry Rules.

Ancient History

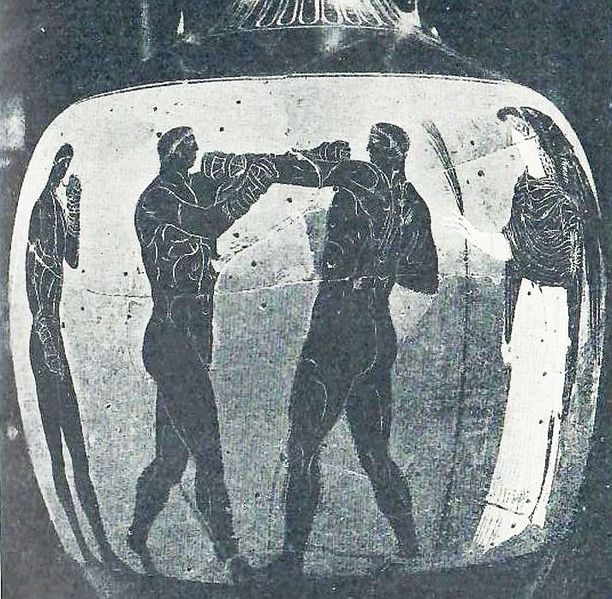

The earliest known depiction of boxing comes from a Sumerian relief in Iraq from the 3rd millennium BC.[2] A relief sculpture from Egyptian Thebes (c. 1350 BC) shows both boxers and spectators.[2] These early Middle-Eastern and Egyptian depictions showed contests where fighters were either bare-fisted or had a band supporting the wrist.[2] The earliest evidence of fist fighting with the use of gloves can be found on Minoan Crete (c. 1500–1400 BC).[2]

Various types of boxing existed in ancient India. The earliest references to musti-yuddha come from classical Vedic epics such as the Ramayana and Rig Veda. The Mahabharata describes two combatants boxing with clenched fists and fighting with kicks, finger strikes, knee strikes and headbutts.[3]. During the period of the Western Satraps, the ruler Rudradaman – in addition to being well-versed in “the great sciences” which included Indian classical music, Sanskrit grammar, and logic – was said to be an excellent horseman, charioteer, elephant rider, swordsman and boxer.[4] The Gurbilas Shemi, an 18th-century Sikh text, gives numerous references to musti-yuddha.

In Ancient Greece boxing was a well developed sport and enjoyed consistent popularity. In Olympic terms, it was first introduced in the 23rd Olympiad, 688 BC. The boxers would wind leather thongs around their hands in order to protect them. There were no rounds and boxers fought until one of them acknowledged defeat or could not continue. Weight categories were not used, which meant heavyweights had a tendency to dominate. The style of boxing practiced typically featured an advanced left leg stance, with the left arm semi-extended as a guard, in addition to being used for striking, and with the right arm drawn back ready to strike. It was the head of the opponent which was primarily targeted, and there is little evidence to suggest that targeting the body was common.[5]

Boxing was a popular spectator sport in Ancient Rome.[6] Fighters protected their knuckles with leather thongs wrapped around their fists. Eventually harder leather was used and the thong became a weapon. Metal studs were introduced to the thongs to make the cestus. Fighting events were held at Roman Amphitheatres.

Medieval and Early Modern London Prize Ring Rules

Records of Classical boxing activity disappeared after the fall of the Western Roman Empire when the wearing of weapons became common once again and interest in fighting with the fists waned. However, there are detailed records of various fist-fighting sports that were maintained in different cities and provinces of Italy between the 12th and 17th centuries. There was also a sport in ancient Rus called Kulachniy Boy or “Fist Fighting”.

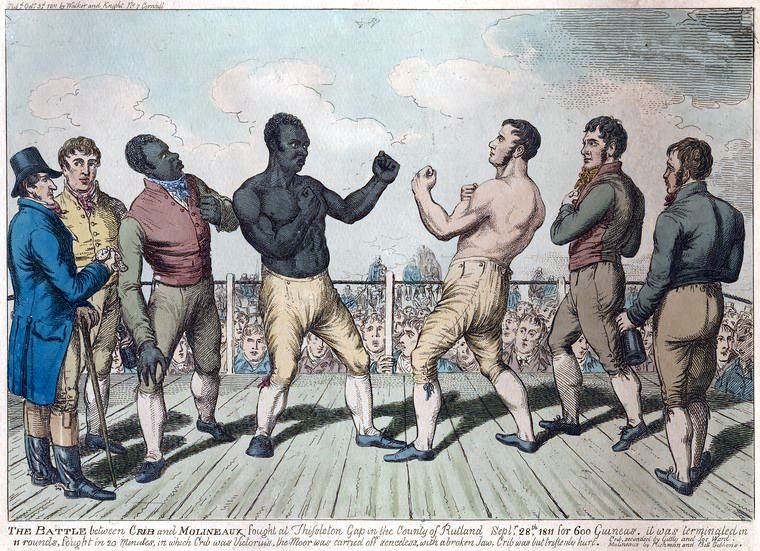

As the wearing of swords became less common, there was renewed interest in fencing with the fists. The sport would later resurface in England during the early 16th century in the form of bare-knuckle boxing sometimes referred to as prizefighting. The first documented account of a bare-knuckle fight in England appeared in 1681 in the London Protestant Mercury, and the first English bare-knuckle champion was James Figg in 1719.[7] This is also the time when the word “boxing” first came to be used. This earliest form of modern boxing was very different. Contests in Mr. Figg’s time, in addition to fist fighting, also contained fencing and cudgeling. On 6 January 1681, the first recorded boxing match took place in Britain when Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle (and later Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica) engineered a bout between his butler and his butcher with the latter winning the prize.

Early fighting had no written rules. There were no weight divisions or round limits, and no referee. In general, it was extremely chaotic. An early article on boxing was published in Nottingham, 1713, by Sir Thomas Parkyns, a successful Wrestler from Bunny, Nottinghamshire, who had practised the techniques he described. The article, a single page in his manual of wrestling and fencing, Progymnasmata: The inn-play, or Cornish-hugg wrestler, described a system of headbutting, punching, eye-gouging, chokes, and hard throws, not recognized in boxing today.[8]

The first boxing rules, called the Broughton’s rules, were introduced by champion Jack Broughton in 1743 to protect fighters in the ring where deaths sometimes occurred.[9] Under these rules, if a man went down and could not continue after a count of 30 seconds, the fight was over. Hitting a downed fighter and grasping below the waist were prohibited. Broughton encouraged the use of ‘mufflers’, a form of padded bandage or mitten, to be used in ‘jousting’ or sparring sessions in training, and in exhibition matches.

These rules did allow the fighters an advantage not enjoyed by today’s boxers; they permitted the fighter to drop to one knee to end the round and begin the 30-second count at any time. Thus a fighter realizing he was in trouble had an opportunity to recover. However, this was considered “unmanly”[10] and was frequently disallowed by additional rules negotiated by the Seconds of the Boxers.[11] In modern boxing, there is a three-minute limit to rounds (unlike the downed fighter ends the round rule). Intentionally going down in modern boxing will cause the recovering fighter to lose points in the scoring system. Furthermore, as the contestants did not have heavy leather gloves and wristwraps to protect their hands, they used different punching technique to preserve their hands because the head was a common target to hit full out. Almost all period manuals have powerful straight punches with the whole body behind them to the face (including forehead) as the basic blows.[12][13]

The London Prize Ring Rules introduced measures that remain in effect for professional boxing to this day, such as outlawing butting, gouging, scratching, kicking, hitting a man while down, holding the ropes, and using resin, stones or hard objects in the hands, and biting.[14]

Marquess of Queensberry Rules (1867)

In 1867, the Marquess of Queensberry rules were drafted by John Chambers for amateur championships held at Lillie Bridge in London for Lightweights, Middleweights and Heavyweights. The rules were published under the patronage of the Marquess of Queensberry, whose name has always been associated with them.

There were twelve rules in all, and they specified that fights should be “a fair stand-up boxing match” in a 24-foot-square or similar ring. Rounds were three minutes with one-minute rest intervals between rounds. Each fighter was given a ten-second count if he was knocked down, and wrestling was banned. The introduction of gloves of “fair-size” also changed the nature of the bouts. An average pair of boxing gloves resembles a bloated pair of mittens and are laced up around the wrists.[16] The gloves can be used to block an opponent’s blows. As a result of their introduction, bouts became longer and more strategic with greater importance attached to defensive maneuvers such as slipping, bobbing, countering and angling. Because less defensive emphasis was placed on the use of the forearms and more on the gloves, the classical forearms outwards, torso leaning back stance of the bare knuckle boxer was modified to a more modern stance in which the torso is tilted forward and the hands are held closer to the face.

Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries

Through the late nineteenth century, the martial art of boxing or prizefighting was primarily a sport of dubious legitimacy. Outlawed in England and much of the United States, prizefights were often held at gambling venues and broken up by police.[17] Brawling and wrestling tactics continued, and riots at prizefights were common occurrences. Still, throughout this period, there arose some notable bare knuckle champions who developed fairly sophisticated fighting tactics.

The English case of R v. Coney in 1882 found that a bare-knuckle fight was an assault occasioning actual bodily harm, despite the consent of the participants. This marked the end of widespread public bare-knuckle contests in England.

The first world heavyweight champion under the Queensberry Rules was “Gentleman Jim” Corbett, who defeated John L. Sullivan in 1892 at the Pelican Athletic Club in New Orleans.[18]

The first instance of film censorship in the United States occurred in 1897 when several states banned the showing of prize fighting films from the state of Nevada,[19] where it was legal at the time.

Throughout the early twentieth century, boxers struggled to achieve legitimacy.[20] They were aided by the influence of promoters like Tex Rickard and the popularity of great champions such as John L. Sullivan.

Appendix

EndNotes

- Note: The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition notes as different pugilism and boxing. Vol. IV “Boxing” (p. 350)[1]; Vol. XXII “Pugilism” (p. 637)[2] Consulted April 17, 2017.

- Michael Poliakoff. “Encyclopædia Britannica entry for Boxing”. Britannica.com. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Section XIII: Samayapalana Parva, Book 4: Virata Parva, Mahabharata.

- John Keay (2000). India: A History. HarperCollins. p. 131.

[Rudradaman] was also a fine swordsman and boxer, and excellent horseman, charioteer and elephant-rider … and far-famed for his knowledge of grammar, music, logic and ‘other great sciences’.

- Gardiner, E. Norman, ‘Boxing’ in Greek Athletic Sports and Festivals, London:MacMillan, 1910, p.402, pp.415-416, 419-422

- Guttmann, Allen (1981). “Sports Spectators from Antiquity to the Renaissance” (PDF). Journal of Sport History. 8 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- “James Figg”. IBHOF. 1999. Retrieved 22 March 2018. excerpting Roberts, James B.; Skutt, Alexander G. (2006). The Boxing Register: International Boxing Hall of Fame Official Record Book (4th ed.). Ithaca, N.Y.: McBooks Press.

- “tumblr_lx13m7QVfb1qa5yan.jpg”. Tumblr. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- John Rennie (2006) East London Prize Ring Rules 1743 Archived 18 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Anonymous (“A Celebrated Pugilist”), The Art and Practice of Boxing, 1825

- Daniel Mendoza, The Modern Art of Boxing, 1790

- “blow-1.jpg”.

- Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014. “Yahoo! Groups”. Groups.yahoo.com. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- Rodriguez, Robert G. (2009). The Regulation of Boxing: A History and Comparative Analysis of Policies Among American States. McFarland.

- Leonard–Cushing fight Part of the Library of Congress Inventing Entertainment educational website. Retrieved 12/14/06.

- “Encyclopædia Britannica (2006). Queensbury Rules, Britannica”. Britannica.com. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- “BBC – London – History – Unlicensed Boxing”. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- “Tracy Callis (2006). James Corbett“. Cyberboxingzone.com. 18 February 1933. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Orbach, Barak. “Prizefighting and the Birth of Movie Censorship”. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- Socolow, Michael. “Why boxing disappeared after the Rumble in the Jungle”. The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

Bibliography

- Accidents Take Lives of Young Alumni (July/August 2005). Illinois Alumni, 18(1), 47.

- Death Under the Spotlight: The Manuel Velazquez Boxing Fatality Collection

- Baker, Mark Allen (2010). TITLE TOWN, USA, Boxing in Upstate New York.

- Fleischer, Nat, Sam Andre, Nigel Collins, Dan Rafael (2002). An Illustrated History of Boxing. Citadel Press.

- Fox, James A. (2001). Boxing. Stewart, Tabori and Chang.

- Gunn M, Ormerod D. The legality of boxing. Legal Studies. 1995;15:181.

- Halbert, Christy (2003). The Ultimate Boxer: Understanding the Sport and Skills of Boxing. Impact Seminars, Inc.

- Hatmaker, Mark (2004). Boxing Mastery: Advanced Technique, Tactics, and Strategies from the Sweet Science. Tracks Publishing.

- McIlvanney, Hugh (2001). The Hardest Game: McIlvanney on Boxing. McGraw-Hill.

- Myler, Patrick (1997). A Century of Boxing Greats: Inside the Ring with the Hundred Best Boxers. Robson Books (UK) / Parkwest Publications (US).

- Price, Edmund The Science of Self Defence: A Treatise on Sparring and Wrestling, 1867 (available at Internet Archive, [3], access date 26 June 2018).

- Robert Anasi (2003). The Gloves: A Boxing Chronicle. North Point Press.

- Schulberg, Budd (2007). Ringside: A Treasury of Boxing Reportage. Ivan R. Dee.

- Silverman, Jeff (2004). The Greatest Boxing Stories Ever Told: Thirty-Six Incredible Tales from the Ring. The Lyons Press.

- Snowdon, David (2013). Writing the Prizefight: Pierce Egan’s Boxiana World (Peter Lang Ltd)

- Scully, John Learn to Box with the Iceman

- weight classification, “2009”

- U.S. Amateur Boxing Inc. (1994). Coaching Olympic Style Boxing. Cooper Pub Group. 1-884-12525-5

- A Pictoral History Of Boxing, Sam Andre and Nat Fleischer, Hamlyn, 1988

- History of London Boxing. BBC News.

- Ronald J. Ross, M.D., Cole, Monroe, Thompson, Jay S., Kim, Kyung H.: “Boxers – Computed Axial Tomography, Electroencephalography and Neurological Evaluation.” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 249, No. 2, 211–213, January 14, 1983.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 09.24.2001, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.